Erica Jurus's Blog, page 9

April 2, 2024

The tradition of pranking and fooling

What’s going on in this photo? Explanation below! photo by E. Jurus, all rights reserved

What’s going on in this photo? Explanation below! photo by E. Jurus, all rights reservedAmidst all the flap about the total solar eclipse coming up next Monday – since our area in Southern Ontario will lie in the path of the totality and up to a million visitors are expected for the event (many of us local residents will be hiding from the onslaught in our own yards) – it turns out that the city of Niagara Falls is going to shut off the Falls so their spectacle doesn’t compete with the spectacle in the sky above.

Just kidding on the last part! Shutting off the Falls (which would be impossible) was a joke by Niagara Falls Mayor Jim Diodati, who was just having a little fun on April Fool’s Day. I thought it was a welcome bit of cheekiness amid weeks of alarmed news articles in our regional media (everything from keeping your pets safe to whether birds will fall out of the sky – no joke on either of those).

We writers love to mess with readers’ minds, to surprise you, particularly if there’s a mystery involved. Red herrings (“a literary device that leads readers or audiences toward a false conclusion”, Wikipedia) are a classic method of misdirection. If you were wondering, as I was, where that term came from, apparently a 19th century journalist and pamphleteer named William Cobbett said he’d used kippers, smelly smoked herrings, to divert hounds from chasing a rabbit.

Media journalists have a long tradition of coming up with ridiculous stories for April 1st – especially in Great Britain, it seems. Some of their pranks have become downright famous.

In 1957 the BBC used its rather serious show Panorama, which bills itself as “Investigative documentary series revealing the truth about the stories that matter”, to deliver an April 1st story about a bumper crop of spaghetti grown by Swiss farmers on trees. According to the report, which was delivered by anchor Richard Dimbleby (a revered figure in broadcasting at the time) to lend a greater air of authenticity to the broadcast public, the combination of an unusually mild winter and very few spaghetti weevil pests had produced a really good harvest. There was even a video showing Swiss farmers picking the sticks of spaghetti delicately off trees and putting them into the sun to dry out.

The idea was created by one of the cameramen for Panorama, Charles de Jaeger, who was known for his cheeky sense of humour and affinity for practical jokes. One of his old school teachers used to tease his class with the remark “”Boys, you’re so stupid, you’d believe me if I told you that spaghetti grows on trees”, and for years de Jaeger had wanted to create a hoax along those lines. At the BBC he found a colleague who loved the idea, and they pitched it to the show’s editor, who gave them a budget of £100 to carry it out.

Well, a lot of people didn’t find the hoax very funny, as it turns out. The BBC was bombarded with calls to either a) settle family arguments about whether spaghetti actually grew on trees, or b) where could spaghetti trees be bought so that people could plant one in their yard. One of the people taken in by the story was Sir Ian Jacob, the BBC’s director-general, who’d been sent a note about the fake broadcast but hadn’t seen it. Oops. (Eventually he became a fan.)

Over the years, appreciative fans carried on the silliness. In 1967, for example, Australian reporter Dan Webb for one of the TV stations said that the country had its own spaghetti-growing region, but the farmers were facing financial ruin because of the proliferation of the “spag-worm”, which unfortunately kept eating the unripe spaghetti from the inside.

My all-time favourite April Fool’s prank completely tickles me as a writer. It occurred in 1977 when the Guardian newspaper published a 7-page “special report” about travelling to the tiny republic of San Serriffe in the Indian Ocean. Consisting of several islands, the main two, “Upper Caisse” and “Lower Caisse”, were in the shape of a semi-colon. The capital city was called Bodoni.

Front page of the Specia Report. source: https://static.guim.co.uk/sys-images/Guardian/Pix/pictures/2012/3/30/1333125088930/San-Serriffe-front-page-001.jpg

Front page of the Specia Report. source: https://static.guim.co.uk/sys-images/Guardian/Pix/pictures/2012/3/30/1333125088930/San-Serriffe-front-page-001.jpgAstute readers recognized that everything about “San Serriffe” was taken from printing terminology. “Serif” is the term for typefaces that have little decorative extensions on their letters, while “sans serif” refers to typefaces that don’t, such as the one I use. Bodoni is a particular typeface still in use today. Everyone who creates computer passwords nowadays will know the difference between ‘Upper Case’ letters and ‘Lower Case’.

But the imaginative perpetrators didn’t stop there. They created a location “northeast of the Seychelles Islands”. It had a size of 9,724 sq. mi., and figures for population, climate, currency (the San Serriffe Corona – re the famous typewriter brand). They divulged some of its history, from its discovery in 1421 by an English adventurer making a landing in the ‘Shoals of Adze’, its colonization by Portugal and Spain, and independence in 1967. As a result of all this activity, it had a mixed population consisting of Europeans, Creoles, Malaysians, Arabs and ‘Flongs’, who spoke their own language of Ki-flong.

There were articles about the politics, including one about the young President-for-life, Maria-Jesu Pica (a font size). San Serriffe was eventually going to crash into Sri Lanka because its islands kept drifting eastwards at the rate of 1,400 metres a year.

They even recruited well-known advertisers to place ‘ads’ in the supplement.

Guinness ran one commenting on the uniqueness of their beer in San Serriffe, where the barley farmers mistakenly planted the seeds upside down, which resulted in a brew that tasted the same, but with a white body and a black head on it.

Kodak said it was running a contest for the best photos people had from San Serriffe, showing the “evanescent beauty of these fabulous islands”. The Guardian itself placed a fake employment ad for a “Reader in Lunar Spectroscopy. With special emphasis on the extraction of energy from moonbeams”. (Quite a few people sent in their résumés.)

A Guardian writer later described the office on publication day as “bedlam”. Phone calls alternated between people wanting more information on the beautiful place and travel agencies and airlines trying to convince people that San Serriffe didn’t actually exist. Hundreds of letters came in, including a group that called itself the San Serriffe Liberation Front and complained about the newspaper’s pro-government slant!

Ever since, the hoax has continued to gather fans all over who’ve embroidered on the tale. A man in Pennsylvania, Henry Morris, published a series of books about San Serriffe, such as the inimitably-named The World’s Worst Marbled Papers: Being a Collection of Ten Contemporary San Serriffean Marbled Papers Showing the Lowest Level of Technique, the Worst Combinations of Colors, and the Most Inferior Execution Known Since the Dawn of the Art of Marbling Collected by the Author During a Five Year Expedition to the Republic of San Serriffe.

Visual hoaxes are just as much fun. I captured a surprising one in the Church of Santo Domingo in Lima, Peru. It’s one of the tiled floors inside, and so effective a piece of trompe-l’oeil that I included some shoes in the photo at the top of this post to help you understand the optical illusion.

Mother Nature isn’t above having a little fun with us as well. In this photo taken in Luray Caverns, Virginia, how much of this small cave is real? It’s not a trick

The tradition of April Fools jokes go way back. Some attribute it to the medieval writer Chaucer, who in his The Canterbury Tales wrote of a vain Chauntecleer rooster being tricked by a fox on a day with this description: “Since March began thirty days and two,” which would possibly mean April 1st. Others, though, think it goes back to the tine of the Great Flood – seriously. The theory is that Noah sent the first dove too soon to search for land, on the first day of April, and therefore the custom arose of commemorating this colossal boo-boo by making fools of people on the same day.

Not everyone is a fan of the April Fools tradition because it can create some serious misunderstandings. A number of times over the decades genuine news published on April 1st have been mistaken for a prank, as when singer Marvin Gaye was shot and killed by his father in 1984. Several of Gaye’s friends didn’t believe the news initially because of the date, including Smokey Robinson and Jermaine Jackson, until they called others and received the sad confirmation.

But all in all, I think light-hearted, playful and clever pranks bring some much-needed levity into our lives.

You can read the entire delightful 7-page San Serriffe spread online at Scribd.

The post The tradition of pranking and fooling first appeared on Erica Jurus, author.

March 26, 2024

Let there be wonder

Fans enjoying a life-size version of Hobbiton created for the LOTR & Hobbit movies in New Zealand – photo by E. Jurus, all rights reserved

Fans enjoying a life-size version of Hobbiton created for the LOTR & Hobbit movies in New Zealand – photo by E. Jurus, all rights reservedOn my television as I write this post, intrepid Sinbad is battling a skeleton raised by the evil sorcerer Sokurah, inside a castle that’s a delightful amalgam of medieval walls, Arabic arches and bottomless stone caverns. There’s a massive green dragon, which, fortunately for Sinbad and the princess he’s to marry, is chained to a rock wall, but outside on their path to escape there’s an angry Cyclops bellowing for their blood. Sinbad releases the dragon from its captivity to battle the Cyclops in magnificent Dynamation, the technique invented by legendary Ray Harryhausen, master of stop-motion special effects in the 1950s to early 1980s.

A couple of weeks ago I watched another Harryhausen movie, First Men in the Moon. While some of the premise was silly, the movie was surprisingly imaginative in its conception of a civilization of insectoid creatures living under the surface of the bright globe we gaze up at every night.

From Sinbad movies to the Percy Jackson and the Olympians series, we the viewers and readers find ourselves enchanted by the stories of fantasy and adventure. The 1939 movie The Wizard of Oz has had an enduring legacy, with everything from the thousands of people still dressing up as the characters for Halloween to literary and musical adaptations to threats to bring on the flying monkeys when someone’s ticking you off.

So it was with some dismay that I read an article about Harry Potter actress Miriam Margolyes more-or-less reprimanding adult fans of the book and movie franchises for their continued enjoyment long past their childhood. Everyone’s certainly entitled to their opinion, so I’m going to offer mine: I completely disagree with her.

For every person that tells us to grow up and leave the joys of childhood behind, I applaud every person who refuses. There’s no harm in enjoying stories that still entertain us (as long as we still keep a foot in the real world, as we all have to). We need elements of fun, and play, in our daily lives – especially these days after weathering a long pandemic, worrying about climate change and having bad news blaring at us constantly.

Psychologists the medical community are all recognizing the health benefits of play, and play comes in all different forms. I read the Lord of the Rings trilogy in my early teens, and decades later my hubby and I spent a fabulous afternoon and evening at the Hobbiton movie set in New Zealand. There were fans there from all over the world, including several wearing elven cloaks, with whom we shared a fantastic hobbit-worthy meal at the Green Dragon Inn, followed by a lantern-lit walk back to Hobbiton and dancing in the Party Field.

A couple of years before that we were in the Universal Studios theme park for a couple of days on a Florida vacation, and I have to confess that I totally geeked out in Knockturn Alley. Yes, I have a darker side, which manifests annually as early as September (or maybe sooner  ) as the weather grows cooler and leaves begin to flutter to the ground.

) as the weather grows cooler and leaves begin to flutter to the ground.

One year hubby and I spent Halloween night in Disneyland, joining hundreds of other people in costume (he was a mad scientist and I was his partially-revived creation) to romp around with the Disney Villains, ride through the Haunted Mansion for the zillionth time and eat Halloween cupcakes until we had sugar overload. There were plenty of families there, but there were more adults in line at the trick-or-treat candy stations than children. By the time fireworks over Cinderella’s castle completed the festivities, everyone there was filled with the magic of a return to childhood for a few hours.

I hope that one day readers of my books will repeatedly revel in the adventures and the ‘worlds’ I’ve created. Growing up is overrated in some aspects, and we should never lose our childish sense of wonder and excitement. Let’s enjoy whatever makes us feel youthful and happy, and don’t let anyone tell you differently.

The post Let there be wonder first appeared on Erica Jurus, author.

March 19, 2024

If someone asked me these questions…

photo by E. Jurus on island of Tahiti – all rights reservd

photo by E. Jurus on island of Tahiti – all rights reservdI’m not anywhere near a famous author – maybe some day, but I was just very happy to write my first book and publish it last year – but I thought I’d have fun answering the questions posed to five authors in a recent article I read. Here’s what I’d have responded.

“Without summarizing it in any way, what would you say your book is about?”

Courage.

“Without explaining why and without naming other authors or books, can you discuss the various influences on your book?”

A few brilliant television series when I was growing up that all speculated on how normal people would handle crazy stuff that came their way: The Twilight Zone, Outer Limits, and the revolutionary Dark Shadows. My brother and I stumbled across Dark Shadows one day (aired on a U.S. station that was hard to pick up by antenna in our area, but our house was by chance in a sweet spot geographically), and were instantly hooked. Soap operas were enormously popular at the time in daytime television, but we’d never seen one that was decidedly spooky1! My mom ended up watching it with me after my brother went off to university, and even she got hooked on it. I loved the idea of a small town with all kinds of supernatural secrets, which of course found its way into my own novel, even though the plot of the entire 3-book series expands far beyond that.

“Without using complete sentences, can you describe what was going on in your life as you wrote this book?”

Covid. Lockdown. Retirement and looking for something to fill my time. Finally the time to take a crack at writing it.

“What are some words you despise that have been used to describe your writing by readers and/or reviewers?”

None yet. All my reviews so far have been very positive, I’m happy to say. If/when the book(s) reach a larger audience, I may come across some I’m not fond of.

“If you could choose a career besides writing (irrespective of schooling requirements and/or talent) what would it be?”

A couple of possibilities: scientific guide on one of the Nat Geo expedition cruises, or safari guide in Africa. Great environments to work in – I love to be outdoors.

“What craft elements do you think are your strong suit, and what would you like to be better at?”

Two strong things that really took me by surprise:

Plotting twisty elements that keep my readers on their toesDialogueI’d like to develop a better imagination for writing horror elements – my brain just doesn’t naturally think that way.

“How do you contend with the hubris of thinking anyone has or should have any interest in what you have to say about anything?”

After I finished my first novel, I was thrilled to have finally done it. But although I thought the idea behind it was pretty good, I had no idea if anyone else would like it. My hubby was my first beta reader, and he really enjoyed it, even though it’s not his usual genre. He was very candid and unbiased, and I made more tweaks. Then it was time to let my assembled group of beta readers take a look at it. They were a good cross-section of potential readers, and their very positive feedback made me feel that the book was worth publishing. (They also gave me insightful comments on things that were working well or not so much). If no one had liked it, I would at least have had the satisfaction of completing a long-standing dream.

* * *

You can find the original article and what the other authors said at Lit Hub Asks: 5 Authors, 7 Questions, No Wrong Answers. Many thanks to Lit Hub for providing the inspiration for this blog post.

1 Another great supernatural soap-style series came out in the same time frame: Strange Paradise. It was short-lived, but pretty cool while it was on.

The post If someone asked me these questions… first appeared on Erica Jurus, author.

March 12, 2024

Interesting things people write about

Spring crocus, surrounded by thousands of acorn shells, in a photo taken last week — taken by E. Jurus, all rights reserved

Spring crocus, surrounded by thousands of acorn shells, in a photo taken last week — taken by E. Jurus, all rights reservedI subscribe to the Public Domain Review newsletter, and I regularly receive tidbits about publications that have recently been released into the Public Domain – i.e. the copyright on the material has passed. I find these tidbits fascinating, especially those from centuries ago. People had different perspectives on life back then, and – ironically in our modern society crowded with technologies that are supposed to save us time – more time to notice the small, often wondrous things in life.

A popular pastime for naturalists over the centuries was the recording of all the signs indicating the arrival of Spring. After a long, often bitter winter (imagine drafty houses without central heating), the first hints of spring were joyful. Signs could range from a bird’s song to the emergence of plants, particularly early-season flowers like snowdrops and crocuses. One dedicated journal was begun by a man named Robert Marsham in Norfolk, England. He made detailed notations until the end of his life, then passed his project on to his family, who remarkably continued for 222 years, only stopping in 1958 when his great-great-great-granddaughter passed away, and her descendants were informed that their work was ‘no longer needed’.

His journal, “Indications of Spring”, has entered the public domain, and his meticulous body of work can be admired by anyone.

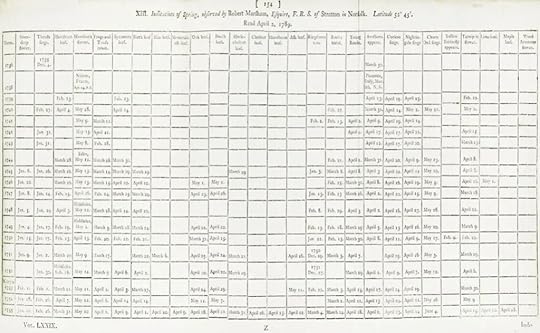

“Records spanning 1736–1755 from “Indications of spring, observed by Robert Marsham, Esquire, F. R. S. of Stratton in Norfolk. Latitude 52° 45’”, originally published in Philosophical Transactions 79 (1789)” (PDR, From Snowdrop to Nightjar – Robert Marsham’s “Indications of Spring” (1789)” — Source: https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rstl.1789.0014

“Records spanning 1736–1755 from “Indications of spring, observed by Robert Marsham, Esquire, F. R. S. of Stratton in Norfolk. Latitude 52° 45’”, originally published in Philosophical Transactions 79 (1789)” (PDR, From Snowdrop to Nightjar – Robert Marsham’s “Indications of Spring” (1789)” — Source: https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rstl.1789.0014And regardless of what modern scientists might have thought of the Marsham family’s ‘amateur’ work, the recordings represent the longest such record for the UK, and have provided a lot of valuable material for tracking changes across the centuries, including our own age of global warming.

The UK Phenology (the study of seasonal natural phenomena) Network, now has more than 20,000 amateur recorders helping it. Other observations are drawn from things like the dates of flower festivals, which have been moving forward each the year, and incidental photographs taken from various sources that carry their own record of what’s growing and blooming. So I guess to some extent my own photographs taken with happiness at seeing spring flowers again have added to the record, even though I haven’t recorded their first emergence. It’s just a personal passion, and I only take pictures, but I completely understand the passion of naturalists like Robert Marsham in taking broad and insightful note of nature’s anticipated change of season.

Bright spring coltsfoot, in a photo taken last week — taken by E. Jurus, all rights reserved

Bright spring coltsfoot, in a photo taken last week — taken by E. Jurus, all rights reservedThe post Interesting things people write about first appeared on Erica Jurus, author.

March 5, 2024

On hiatus this week

The post On hiatus this week first appeared on Erica Jurus, author.

February 27, 2024

Hiatus tidbit: What’s Real?

Descending into the many layers of the London Underground – photo by E. Jurus, all rights reserved

Descending into the many layers of the London Underground – photo by E. Jurus, all rights reservedA brief post, in honour of the famous London Tube map. Such a massive construction, with miles of old tunnels in a very old city smoldering with history and mystery, just fires the imagination. Film and TV producers have had a great deal of fun inventing subways stations that ‘aren’t on the official map’. There are a lot of these imaginary stations, which perhaps we’ll delve into in a future post, but here’s a fun blog to start with, A list of London’s fictional tube stations. Shout out to London resident Ian Mansfield for putting this together.

The post Hiatus tidbit: What’s Real? first appeared on Erica Jurus, author.

February 20, 2024

How a humble subway map became an icon

Standing on a platform of one of the London Underground’s subway stations

Standing on a platform of one of the London Underground’s subway stationsThere’s a dragon approaching. You can feel its hot breath billowing out of the dark, sooty-looking tunnels. Soon it will emerge and devour you.

That was my first impression of the subway system in London, England. At its deepest levels, it’s like a medieval labyrinth. As the trains get close to the platforms where riders wait, they push air ahead of them, so you don’t really need to look at the myriad of electronic signs counting down the arrival times to know that a train is near.

My hubby and I were fascinated by the subway system, affectionately known as The Tube because of the shape of its tunnels. As visitors, it didn’t take us long to figure out that The Tube was the easiest, fastest way to get to points of the city that were too far to walk to. Nor did it did take us long to figure out the system itself, thanks to a brilliant, colour-coded map designed in 1931 by a man named Harry Beck. He did it so well that the map itself, showing all of the different ‘lines’ and their stops, as well as where several of the lines intersect so that you can transfer from one to another, has become an iconic symbol of London. If you’ve been there, you know exactly what I’m talking about.

External signs for the Tube stations are instantly recognizable from the graphic symbology

External signs for the Tube stations are instantly recognizable from the graphic symbologyOf course, the city’s subway system is remarkable in itself, transporting you pretty much anywhere you need to go – even out to Heathrow Airport. I’m sure the citizens of London are fairly blasé about it, but we rather enjoyed the experience, especially when some of the trains exit the tunnels and run along the surface – they gave us intimate views of parts of the city we’d never have seen otherwise.

London is one of the most layered and engaging cities in the world. Its origins go as far back as the Bronze Age, with remnants of early settlers around 4800-4500 B.C. During Roman occupation it was known as Londinium, and you can still see pieces of old walls. Over the centuries, London accumulated an incredible number of famous landmarks, but even the residential streets with brown brick buildings and small fenced yards that you see as your train rattles past them tell their own stories.

The London Underground (the official name of the subway system) began its life in 1863, as the Metropolitan Railway. When we first visited, you could easily see the age of parts of it in the weathered old wood-surfaced escalators taking you deep into the bowels of the earth and back out. None of those wooden antiques exist any longer, after a fire under one of them spread from the massive King’s Cross St Pancras Station through several lines. By 2014 everything had been converted to metal, but I’m glad my hubby and I got to ride on the rickety, wood-slatted steps while they still existed.

Today, the Underground has 250 miles of track, covered by 11 different lines. Almost 5 million passenger trips are made daily, embarked on through 272 stations. Forty-five percent of the system is under ground; most of the more outlying portions are on the surface, serving Greater London and out to the counties of Buckinghamshire, Essex and Hertfordshire. It runs past every-day and historic, humble and exalted, all intrinsic parts of an amazing city.

A subway train runs strikingly past old and new, including the venerable Black Friars pub.

A subway train runs strikingly past old and new, including the venerable Black Friars pub.As you might imagine, producing a portable map (that could be folded neatly and carried around in a coat pocket) of the massive system for residents to use was quite an undertaking. There were many maps before the one that became official. Early versions tried to illustrate everything with geographical accuracy, which proved impossible. Even at that time, a maze of lines criss-crossed a few squares miles of central London, but also stretched 50 miles from the central part of the city. In central London, there were some stations just a couple of hundred yards apart, while others were over a mile from each other. Those early maps tended to concentrate on the city itself, while far-flung stations were largely ignored by the designers.

In 1931, Harry Beck, a young engineering draughtsman who’d joined the Underground Group’s Signal Engineer’s Office in 1925, realized thatwhat passengers really needed to know was where the lines ran and how to get from one place to another as efficiently as possible.

He drew the different lines very simply on a grid, running either vertically, horizontally or at 45-degree angles to make them easy to follow visually. Then he listed all the stations in order, not by proximity, as well as where to change between lines. The lines were colour-coded to make them easily distinguishable from each other. When Beck first presented his map to Underground management, it looked pretty radical to their eyes, so they did a test print of 500 copies, which were distributed in 1932 from a handful of stations. In 1933 another 700,000 copies were made. Within a month, more had to be printed. The draughtsman had seen straight inside riders’ heads to create a map that was actually useful.

The upcoming updated Tube map, showing the new lines and colours; converted for posting to jpeg from the PDF available at the Transport For London website,

The upcoming updated Tube map, showing the new lines and colours; converted for posting to jpeg from the PDF available at the Transport For London website, Beck tweaked the map over the years, refining his design and incorporating changes to the system as they came along. To this day, versions of his map are handed out to everyone who buys a one-day to multi-day ticket, and relevant sections are available on the walls of each station as well as in the panels above the windows of each train car. The colour-coding gives the map a fun, almost child-like quality, and an artistic flair that has captivated users for decades.

Visitors can buy a copy of the map on mugs, t-shirts and a variety of other souvenirs (we had a mug, but used it so much that the design began to wear off). In 2006 the “Tube map” was voted a national design icon. If you’ve been reading my blog for a while, you’ll know what I mean when I write that each subway line on the map has its own official Pantone colour. The Piccadilly Line, which runs all the way into the city from Heathrow, through King’s Cross St Pancras, and up to the northeast, is Pantone 072 – Corporate Blue; my hubby and I have ridden that line a lot over various visits, coming in from the airport and staying in Bloomsbury around Russell Square.Central Line, which runs through the heart of the city, is Pantone 485 – Corporate Red.

The names of some of the stations are delightful, as only British whimsy can manage: Tooting Bec, Nunhead, Pudding Mill Lane. Others are evocative of the city’s layers of history – Covent Garden, West India Quay, Whitechapel.

Recently the six newest lines have been given names that have historical/cultural significance, and are being marked on the map with double lines. They’ll also receive their own unique colour. The Lioness Line, for example, identified by two yellow lines, runs by Wembley and recognizes the achievements of the England women’s football team. And so the famous map evolves again.The Tube map is such a part of the London experience that you really have to go there and run around with it to fully appreciate how magnificently it conveys the information needed to get around. Beyond strolling the atmospheric streets around places like Buckingham Palace, Westminster or Knightsbridge, to get to places like the Tower of London simply find which Tube station is nearest to it, pull out your trusty subway map and trace your path there from your current location. (Of course, you could just take a cab, another iconic London experience, but you’ll miss the fun of exploring the oldest subway system in the world.)

Maps were created to help people find their way. Take a trip to London and enjoy the Tube map’s clever design as much as you enjoy the many places it will take you to.

All photographs in this post were taken by me, and all rights are reserved. E. Jurus

The post How a humble subway map became an icon first appeared on Erica Jurus, author.

February 13, 2024

Not just words

This past autumn, archaeologists working in Turkey in the ruins of the ancient Hittite capital Hattussa around 100 miles east of modern Turkey’s capital, Ankara, discovered a previously unknown ancient Middle Eastern language that had been lost for up to 3,000 years.

The Hittites were one of the dominant powers of the Near East between the 15th and 13th centuries BC, even conquering Egypt for a time. Their empire stretched from the Aegean Sea in the west to northern Iraq in the east, and from the Black Sea in the north to Lebanon in the south. Their civilization changed human history with technological innovations like the use of iron, their famous war chariots and the creation of a substantial civil service.

Massive empires are run by information, and this ancient domain was no different – the civil service scribes kept voluminous records, all in a Hittite version of a pre-existing Mesopotamian script called cuneiform, which consisted of wedge-shaped lines arranged in groups representing syllables.

During excavations over recent decades, around 30,000 clay tablet documents have been unearthed. Most were written in the empire’s main language, Hittite, but around 5 percent were in the languages of the empire’s minority ethnic groups from various parts of Anatolia, Mesopotamia and Syria.

The area where modern Turkey now lies was, in ancient times, rich in languages. Currently only five minority languages have been known from the time of the Hittites, but there would once have been many more, making this recent discovery very exciting. The newly-discovered language is being called Kalasmaic, apparently spoken by a conquered group of people in an area called Kalasma on the empire’s northwestern fringe. Its discovery opens up a bigger window into one of the largest administrative regions in history.

What is language? We speak it every day, having learned it as a child, and having expanded our vocabulary over time. You’re reading this in English, obviously, which I’ve studied over the years to find fluidity and eloquence as a writer. I was also a member of Toastmasters for several years to learn how to express myself better orally (and not freeze up in meetings at work, which were the bane of my existence for years beforehand).

In high school I studied French (Canada’s second language) and Latin (because I thought it was interesting). But before I began elementary school I was fluent in German, which we spoke at home. I’m rusty on the German and French now because I don’t have many opportunities to use them, but in my travels I’ve used them both, as well as picking up some Spanish.

According to the internet, there are over 7,000 languages in the world – far more than most of us would think or be able to name. But according to The Bible, depending on how much you might believe as a historical document:

Genesis 11:1-9 (NIV)

Now the whole world had one language and a common speech.

This sentence in The Bible begins the story of the Tower of Babel, and it’s a very curious tale.

As a species, we arose in Africa. Language – using sounds, then groups of sounds, then words and sentences – is believed to have developed as early humans needed to convey information, about food, danger, etc. No one will ever know for sure of the exact timeline, but over the millions of years in which we evolved physically, it wasn’t until we became homo sapiens that we had the right vocal equipment to produce speech. It’s believed that we began ‘speaking’ to each other about 20,000 years ago.

It’s extraordinary that humanity existed for 7 million years without being able to talk amongst themselves. What a quiet place the planet must have been, just the sounds of nature and the few sounds early humans could have made (grunts, yells?). Sounds rather pleasant, doesn’t it?

Around 2 million years ago, early humans began dispersing beyond Africa. The first cave painting, the earliest form of communication that our species has, dates back to over 64,000 years ago (using uranium-thorium dating) and was made by a Neanderthal.

Once humans began moving to different places in the world, and then developed speech, it’s a bit of a stretch to believe that the entire world had only a single language, as stated in Genesis. Yet there’s that chronicle, which goes on to say:

As people moved eastward, they found a plain in Shinar and settled there.

They said to each other, “Come, let’s make bricks and bake them thoroughly.” They used brick instead of stone, and tar for mortar. Then they said, “Come, let us build ourselves a city, with a tower that reaches to the heavens, so that we may make a name for ourselves; otherwise we will be scattered over the face of the whole earth.”

But the Lord came down to see the city and the tower the people were building. The Lord said, “If as one people speaking the same language they have begun to do this, then nothing they plan to do will be impossible for them. Come, let us go down and confuse their language so they will not understand each other.”

So the Lord scattered them from there over all the earth, and they stopped building the city. That is why it was called Babel—because there the Lord confused the language of the whole world. From there the Lord scattered them over the face of the whole earth.

The words of the story leave a lot out. Why were the people so determined to build the tower, for example? (Scholars have speculated that this was a post-Flood attempt to catastrophe-proof themselves.) What’s meant by the tower ‘reaching the heavens’? (The sky? God’s domain?) Why was God so worried about anything us piddly humans could do anyway? It’s unclear, but God actually reached down and made the people no longer able to understand each other, which was as good a way of messing things up as any.

The effect of confusing our language was profound. The people gave up their construction entirely, even though surely they still remembered how to build, and left the region to go and live somewhere else.

Scholars believe this was a tale not to be taken literally, but to explain the existence of multiple languages and cultures in the world.

Being able to understand and speak another language opens up travel in amazing ways. My hubby and I always try to learn a few words in the language of the country we’re visiting, as a courtesy to the people who live there. We picked up a little Arabic for our trip to Egypt, a little Indonesian for visiting Java and Bali, brushed off our high school French for a jaunt to Paris…

When we were in Peru, where Spanish, Quechua (the language of the Inca people), and Aymara are the official languages, and English is spoken to some degree, I was able to communicate fairly well in my travel Spanish. Spanish is one of the “Romance” languages, derived from Latin (the high school stuff has come in handy), and with the aid of that base reference and a vocabulary book, I made out pretty well. But when we visited two islands in Lake Titicaca, including an overnight ‘home stay’, it was a challenge to manage more than a couple of words in Aymara, which is unlike any other language we’ve come across. It’s certainly not related to Latin, and possibly not Quechua either. Thankfully for travellers, people on the islands and in neighbouring Bolivia also speak Spanish, and if I wanted to purchase a handicraft or ask a question, I was able to get by, and I felt very empowered to be able to manage even that small level of communication.

As a lot of us growing up in the 20th century had drilled into us, Words are Important. So is writing them down in a form that others can read.

The Bible isn’t the earliest piece of compiled and written oral traditions in history – writing goes back to ancient Sumer, dating to between c. 3350 – c. 2500 BC (or BCE). Writing, even in its most basic forms, opened up a whole new world of preserving information. But not all writing is necessarily in a form we’d recognize

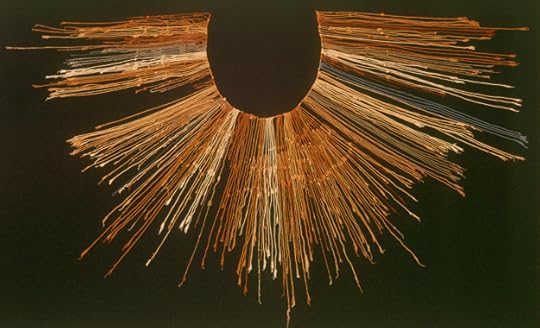

For example, for a long time historians have believed that the Inca, builders of the largest empire in South America, had no form of writing; all the information about one of the greatest cultures in history has come from the Spanish invaders, and from surmises made from artwork and other cultural artifacts. The Inca had a complex counting system using coloured strings with knots in them, knows as “quipu”, but there are very few surviving quipu to study.

An Inca quipu, from the Larco Museum in Lima

An Inca quipu, from the Larco Museum in LimaBy Claus Ableiter nur hochgeladen aus enWiki – enWiki, hochgeladen von User Lyndsaruell; siehe http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image:Inca_Quipu.jpg, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2986739

What’s been known about quipu, or khipu, is that the Inca people used them for keeping calendrical and numerical records of various things like taxes, census records, military organization. The knots recorded data using a base-ten numerical system, with the absence of a knot in specific positions to represent ‘zero’.

Seems straightforward enough, but a single quipu could have only a few cords, or up to thousands of them. And in recent years, some researchers have begun to speculate whether those cords also contained a form of writing/language that we aren’t familiar with. Recently, American anthropologist Sabine Hyland believes she’s begun to make headway in understanding the language, identifying 95 combinations of colour, ply and type of fibre; that would be enough to comprise a writing system.

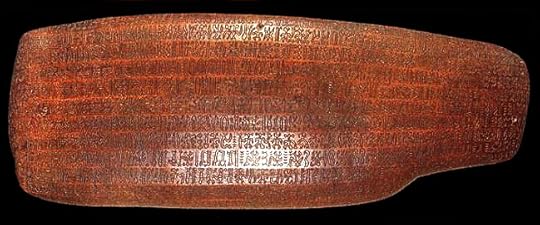

There are still a variety of writing systems we’ve never deciphered, because they’re so different we don’t even know where to start. Rongorongo, the writing found on Easter Island, is one of them.

Verso of rongorongo Tablet B, Aruku Kurenga.

Verso of rongorongo Tablet B, Aruku Kurenga.By Rongorongo_B-v_Aruku-Kurenga_(color).jpg: unknown *derivative work: Mfield (talk) – Rongorongo_B-v_Aruku-Kurenga_(color).jpg, Public Domain, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=34608081

Archeologists aren’t even certain that the markings, on some two dozen surviving artifacts, are writing/language, but their precise positions in long strings on layers of lines look like they’d be strings of information. However, if you look at the sample above, there’s no punctuation or spacing to help delineate words and sentences, at least none that we recognize.

Linear A, used by the ancient Minoan civilization in palaces and for religious writings, is another famous undeciphered language, although it is recognized as script,. It was succeeded by Linear B, which has been deciphered, but Linear A remains a mystery.

We take languages for granted, but there are still so many that we can’t read, that are rare and disappearing, and that have even gone extinct when the last known speaker passed away.

For centuries people had no idea what all those beautifully-scribed hieroglyphs in Egypt were saying, as the knowledge of carving them disappeared around the 3rd century A.D. It wasn’t until Napoleon’s expedition to Egypt in 1798 discovered the Rosetta Stone. This piece of black basalt, by a great stroke of luck, contained the same message in hieroglyphs, Demotic (another script that was used for documents as a kind of early ‘short-hand’), as well as – and this was the key to everything – in ancient Greek.

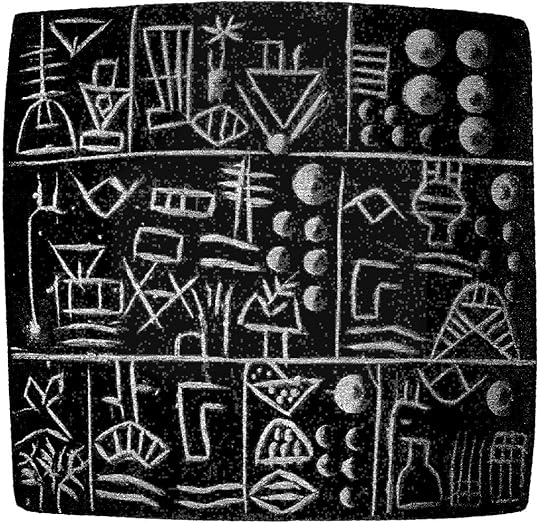

Cuneiform is the earliest known writing system, developed in ancient Sumer, which, as you might guess, is the earliest known civilization (a complex society that developed a governing body, social stratification, community living in a city/multiple cities, and a writing system). Sumer was located in southern Mesopotamia (what’s now south-central Iraq) in the early Bronze Age. In the valleys of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, Sumerian farmers were able to grow an abundance of grain and other crops, which enabled them to stop being nomadic and form urban settlements.

Because the messenger’s mouth was heavy and he couldn’t repeat [the message], the Lord of Kulaba patted some clay and put words on it, like a tablet. Until then, there had been no putting words on clay.

Those words are from a Sumerian epic poem, Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta. c. 1800 BC, explaining the story of writing. Scribes used specially-cut reeds to produce a stylus that created the distinctive wedge-shaped characters that were then pressed into pieces of soft clay.

The cuneiform script was developed from an early form of what’s called “proto-writing” that was pictographic. The problem with recording in stylized pictures is that it’s cumbersome and time-consuming, and it was inevitable that, as the Sumerian civilization grew, they’d develop something that could be stamped in the clay a little faster.

Proto-cuneiform tablet, Jemdet Nasr period, c. 3100–2900 BC.

Proto-cuneiform tablet, Jemdet Nasr period, c. 3100–2900 BC.By Barton, George A. (12 November 1859 – 28 June 1942) – Origin and Development of Babylonian WritingPublished 1913, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=77733268

Tomb of Darius I DNa inscription part II

Tomb of Darius I DNa inscription part IIBy Diego Delso – This file has been extracted from another file, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=75161226

Over the course of its history, cuneiform was adapted to write a number of languages in addition to Sumerian.

A vast amount of cuneiform tablets have been recovered from archeological digs – between 500,000 and two million cuneiform tablets are estimated, of which only approximately 30,000–100,000 have been read or published so far. The British Museum holds the largest collection (approx. 130,000 tablets). Decipherment of cuneiform began in the late 1700s and translation of historical records continues to this day.

The unearthing of tablets with a newly-recognized language emphasize how much of the past is still waiting to be discovered, in ideas and even statistics, passed on across the centuries through words and phrases recorded where some day they could once again be read.

The post Not just words first appeared on Erica Jurus, author.

February 6, 2024

1000 words in gardens

There’s a well-worn saying that claims that a picture is worth a thousand words. It’s attributed to an advertising maxim coined in the 1920s, but Fred R. Barnard, who promoted the idea, said he took it from an old Chinese proverb. Whatever the case may be, photos can convey imagery that takes our breath away. As a writer, I believe a few well-chosen words, the kind that become poetry, can do the same, but I love photographs for their visual impact, especially of gardens and nature, which to me reveal the soul of our planet.

Recently the International Garden Photographer of the Year competition 2024 announced its winning photographs, and they are wonderful. Some of the photographers used very specialized techniques to bring us images that truly capture nature in all its magnificence.

It can be nigh impossible to describe gardens and their contents in the amount of breathtaking detail that a photo offers, nor would a writer want to — readers would quickly tune out. And so I love taking and posting photos as much as I love writing. In this post I’m sharing a few I took last spring and summer, for their beauty and as a reminder on a chilly winter day that sun, warmth and the growing season are just a few weeks away. All photos in this post were taken by me, and all rights are reserved.

I wanted to capture the gorgeous details of this nodding magenta-coloured lily.

I wanted to capture the gorgeous details of this nodding magenta-coloured lily. A dragonfly stayed still long enough on a lily pad to photograph the lace-work of its magnificent wings.

A dragonfly stayed still long enough on a lily pad to photograph the lace-work of its magnificent wings. Sunlight through petals and reflections in water mesmerize me.

Sunlight through petals and reflections in water mesmerize me. I love the shades of green surrounding a burst of red nasturtium flowers in this photo, and the wonderful textures of the foliage.

I love the shades of green surrounding a burst of red nasturtium flowers in this photo, and the wonderful textures of the foliage. On a pond I was able to capture these geese and their feet under the water.

On a pond I was able to capture these geese and their feet under the water. Bees are challenging subjects because they move constantly while gathering pollen. I chase them around a lot.

Bees are challenging subjects because they move constantly while gathering pollen. I chase them around a lot. I also love garden objects and the ways that flowers and plants form works of art with them.

I also love garden objects and the ways that flowers and plants form works of art with them. One of the best sights in spring, if you’re lucky enough to be near some: froths of cherry blossoms. There are a number of ornamental cherries growing along the Niagara Parkway, bursting forth every May.

One of the best sights in spring, if you’re lucky enough to be near some: froths of cherry blossoms. There are a number of ornamental cherries growing along the Niagara Parkway, bursting forth every May.The post 1000 words in gardens first appeared on Erica Jurus, author.

January 30, 2024

Searching the Stars

This week we look out to the stars. What’s really out there, besides what we can see when we look up at the night sky?

For thousands of years, humans have been paying attention to both the life- and warmth-giving sun during the day, and what was revealed above us after the sun set. They noticed the changes in the moon throughout the lunar months, as well as clusters of stars that they thought resembled animal shapes. There are cave paintings 30,000 years old that depict their observations.

There were constants, like the Big Dipper and Orion, that allowed sailors to navigate the seas. Star charts were being created more than 1,000 years BCE.

It’s believed the Babylonians observed the passage of Halley’s Comet. Life in ancient Egypt depended on the flooding of the Nile River to grow crops, and when the people discovered that the event recurred about every 365 days, they created the first calendar very similar to ours. Indigenous North Americans oriented stone markers to the Sun and stars so they could chart the arrival of summer, while southward, the Mayans built special buildings to make astronomical observations and by 800 A.D. had a calendar more accurate than the one used in Europe.

Clearly the heavens have been on our minds for millennia, allowing us to make calculations about what was coming throughout the year. But beyond that, inventors began producing telescopes in the Middle Ages, allowing them to look further than the naked eye.

During the Renaissance, astronomer Giordano Bruno was the first to suggest that all those twinkly stars in the blackness of the firmament were distant suns. He also believed in intelligent life out there, which earned him the attentions of the Inquisition, unfortunately. But work began in earnest about what exactly was up there, and it hasn’t abated any time since.

In the 19th century, scientists discovered that there were forms o light we couldn’t see – gamma rays, UV radiation, radio waves…

It was an American physicist who in 1933 discovered radio waves emanating from the Milky Way, and the science of radio astronomy was born.

Radio astronomy is another way of making observations about the universe than using visual cues. According to the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO):

“There’s a hidden universe out there, radiating at wavelengths and frequencies we can’t see with our eyes. Each object in the cosmos gives off unique patterns of radio emissions that allow astronomers to get the whole picture of a distant object. Radio astronomers study emissions from gas giant planets, blasts from the hearts of galaxies, or even precisely ticking signals from a dying star.”

The NRAO is headquartered in Virginia, but it oversees radio telescopes in numerous locations. Probably the most famous of these is the Very Large Array (VLA) in Socorro, New Mexico. Actress Jodie Foster’s character, Ellie Arroway, spent a lot of time there in the 1997 movie Contact, based on the novel by Carl Sagan.

During our visit to the Very Large Array, the antennas were clustered together. Photo by E. Jurus, all rights reserved.

During our visit to the Very Large Array, the antennas were clustered together. Photo by E. Jurus, all rights reserved.“Who are we? We find that we live on an insignificant planet of a humdrum star lost in a galaxy tucked away in some forgotten corner of a universe in which there are far more galaxies than people.” Carl Sagan

The New Mexico array is named after the man now considered a founding father in radio astronomy, none other than Karl Jansky. His discovery of radio waves was one of those ‘happy accidents’ that he recognized the importance of. At the age of 22, he was hired by Bell Telephone Labs to investigate short waves and whether their static might interfere with radio transmissions here on earth.

He built a directional antenna about 100 feet in diameter, mounted on a turntable with a set of four wheels from a Model-T Ford car, allowing him to rotate the antenna to determine the direction of signals it received. After spending several months recording signals from many directions, Jansky grouped them into the following: static from nearby thunderstorms, storms farther away, and something of unknown origin.

Jansky spent over a year trying to figure out the third kind. At first it seemed to come from the sun, but after a few months it moved away from that position. And it repeated, on a cycle of 23 hours and 56 minutes. After consulting with an astrophysicist, Albert Skellett, and comparing his observations with astronomical maps of the time (which were based on optical data), Jansky concluded that the radiation came from out in the Milky Way. He called it “Star Noise”.

He announced his discovery at the time, but few people understood the significance, and his requests to investigate further got little support, especially not financially from Bell Labs, who were directing their dollars towards trans-Atlantic communications.

A few scientists were interested, but the concept of “radio” astronomy didn’t catch on for several years, partly because it was the Great Depression at the time and funding wasn’t forthcoming, and because Jansky didn’t have strong credentials – only a Bachelor of Physics. However, in 1937 a radio engineer named Grote Reber built a radio telescope in his back yard and began conducting radio-wave research, followed by John Kraus, who built a radio observatory at Ohio State University after WW2.

Imagine the wonders that this new method of astronomical research began to reveal. Kraus himself said,

“In 1930 essentially all that we knew about the heavens had come from what we could see or photograph. Karl Jansky changed all that. A universe of radio sounds to which mankind had been deaf since time immemorial now suddenly burst forth in full chorus.”

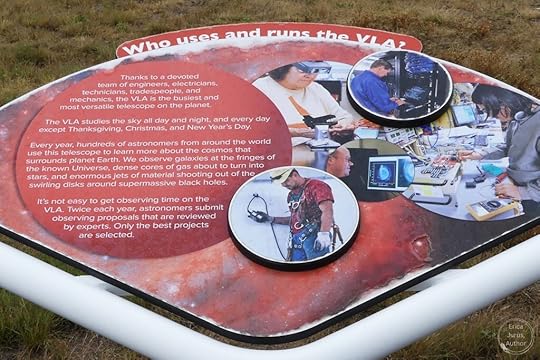

You can visit the Very Large Array in New Mexico, and it’s a fascinating place. My hubby and I were lucky enough to be in the area in the fall of 2022, just a week after the Array reopened to the public post-pandemic.

We practically had the place to ourselves. It was a rainy day, but we bundled up, toured the extensive information provided in the Visitor Centre, and then were allowed to wander all over pretty freely, right out to the closest of the 28 radio telescopes. There were signs with even more information at each stop on the self-guided tour.

They’re not small items. The receiving dishes are 82 feet across, and each antenna, including the complex base it’s mounted on, weighs 209 metric tons.

To give you an idea of the size of the antennas, I’m standing at the bottom of one, below the stairs on the front left of the photo, in an off-white jacket and pants. Photo by M. Jurus, all rights reserved.

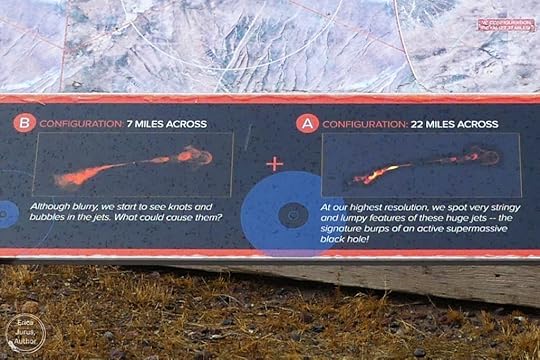

To give you an idea of the size of the antennas, I’m standing at the bottom of one, below the stairs on the front left of the photo, in an off-white jacket and pants. Photo by M. Jurus, all rights reserved.Twenty-seven of the antennas are ranged along the arms of a Y-shaped track, and can be moved around into different configurations to suit the needs of the researchers. The array basically acts as a single antenna whose ‘diameter’ can be changed by drawing its 27 components either closer together or farther apart. They can be sent as far apart as 22 miles or all pulled within one mile at the closest alignment.

Photo by E. Jurus, all rights reserved.

Photo by E. Jurus, all rights reserved.When we visited, the Array was in Configuration “C”. the second smallest.

Photo by E. Jurus, all rights reserved.

Photo by E. Jurus, all rights reserved.The antennas were resting on their stationary foundations, which may not look like much, but they rise 6’4” above the ground, and another 32’ below to hold up their massive burdens.

Photo by E. Jurus, all rights reserved.

Photo by E. Jurus, all rights reserved.There is a 28th antenna, kept as a spare. When we visited, one out on the Y was looking wonky – it was pointing straight upward instead of at a specified angle, what the staff amusingly referred to as “bird nest” mode – and there was another in the on-site repair shop, perhaps waiting to be deployed.

The ‘bird-nest’ antenna. They seem to have a mind of their own on occasion. Photo by E. Jurus, all rights reserved.

The ‘bird-nest’ antenna. They seem to have a mind of their own on occasion. Photo by E. Jurus, all rights reserved. Spare antenna in the on-site garage. Photo by E. Jurus, all rights reserved.

Spare antenna in the on-site garage. Photo by E. Jurus, all rights reserved.The Array achieves an impressively detailed resolution across immense distances of space: as fine as between 0.2 and 0.04 arcseconds. To put that into context, an arcminute is a unit of measurement equal to 1/60th of one degree, i.e. of a full circle. An arcsecond is even tinier, 1/60th of that.

A section of one of the explanatory signs out on the tour, explaining what can be ‘seen’ at different configurations. Photo by E. Jurus, all rights reserved.

A section of one of the explanatory signs out on the tour, explaining what can be ‘seen’ at different configurations. Photo by E. Jurus, all rights reserved.The scientists conducting research generally aren’t on site – they submit projects from all over to the Array and request use of the antennas. Operators at the site maneuver the antennas and relay the results to the relevant scientists. Nobody lying around on the hood of a car with headphones – sorry.

Photo by E. Jurus, all rights reserved.

Photo by E. Jurus, all rights reserved.The Array was built in the 1970s, then tweaked in 2011 to allow new technology. It remains the most powerful and most flexible instrument of its kind. According to the NRAO, more than 3,700 planets in 2,700 star systems have been confirmed, and scientists have been able to follow radio waves all the way back to the afterglow following the Big Bang.

And starting early this year, the Array is getting a major facelift. It will become the Next Generation Very Large Array (ngVLA). Construction on a prototype antenna dish will begin in this very month; it’s expected to take an entire year, followed by the building of more than 200 additional new antennas over the next dozen years or so. The old dishes will stay online while the next generation is developed.

The current construction estimate for the ngVLA is $2.3 billion, and it’s expected to cost $93 million per year in operational costs once it comes online, but the new version may be able to do things like shed new light on how planets form. The new antennas will be lighter, smaller, and less expensive to construct and maintain than the original dishes. In addition, they won’t need to move on tracks, as they currently do every four months (either pulled together for observing large-scale structures or pushed apart to see detail, but not both aspects at the same time).

We were able to see, and stand on, the miles of track that the big dishes chug around on; we’d have loved to see them on ‘moving’ day! Nevertheless, we felt privileged to have such an up-close-and-personal look at such an amazing research instrument that lets our world see far, far out into the heavens to find out what people have been wondering for such a long time: what’s out there?

Some of the miles of track that the antennas move around on. Photo by E. Jurus, all rights reserved.

Some of the miles of track that the antennas move around on. Photo by E. Jurus, all rights reserved.On January 8 just this year, an international team of astronomers announced that they’ve found a mysterious star formation at the far edge of the galaxy M83. The research used several instruments, including the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array (VLA). One of the things researchers do is look for “molecular clouds” – the evidence of formation of new stars. This team discovered 23 molecular clouds that showed a different type of star formation, providing an important clue to the physical processes that lead to star formation in general. They’re very excited.

Also on January 8th, it was announced that the SETI Institute’s COSMIC project (“Commensal Open-Source Multimode Interferometer Cluster”, if you were wondering) at the Very Large Array is expanding the search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI). How cool is that?! The COSMIC cluster is specially designed for future upgrades, allowing it to do much more than search for extraterrestrial intelligence – to finding more stars, exploring new radio wave frequencies, and studying all kinds of leading-edge concepts like dark matter.

If you’re interested in learning more about SETI, check out its posting A Primer on SETI at the SETI Institute. And while everyone conducts amazing research, you can visit the Array personally, as we did. It’s open 362 days a year (closed on Thanksgiving, Christmas Day, and New Year’s Eve), daily from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m., and you can take the same self-guided tour we did, that ends at the base of one of the giant antennas. Visit public.nrao.edu/visit/very-large-array for information.

We stayed in Socorro, where most of the VLA staff live. The drive out to the Array is easy along paved roads, and runs through some wonderful New Mexico scenery. You can see the Array from the main road, and it becomes even cooler when you turn off onto the property and all the antennas start coming into view. I don’t know if you can find out in advance the days that the antennas are moved around (they were listed on a poster when we visited), but that would indeed be something to see.

“I want to know what dark matter and dark energy are comprised of. They remain a mystery, a complete mystery. No one is any closer to solving the problem than when these two things were discovered.” Neil deGrasse Tyson

N.B. Re my January 16th post: I came across a full episode of the Expedition Unknown TV series with explorer Josh Gates dedicated to Tiwanaku, and it’s excellent. Atlantis of the Andes, S6.E3.

View from the road the day we were there. Photo by E. Jurus, all rights reserved.

View from the road the day we were there. Photo by E. Jurus, all rights reserved.The post Searching the Stars first appeared on Erica Jurus, author.