Whitney Robinson's Blog, page 2

July 3, 2011

how existential!

I promised bleakness and existentialism last time, but suffered a metaphysical crisis in trying to deliver. But why not let my past self do the work? I did not, after all, suffer a tri-weekly dose of breakdown-inducing philosophy in my junior year for nothing! So here for your (possible) amusement I've decided to post my Existential Philosophy term paper from way back when–which is to say, when I was 21, which sadly is starting to feel like 'way back when'. Looking back, most of my undergraduate essays are pretty grim, and I can only imagine how bad the rest of the papers must have been for mine to receive 'A's. Actually, I was a teaching assistant, so I know exactly how bad they were. One might expect that most college sophomores would be capable of forming grammatically correct, economical, and globally comprehensible sentences at least some of the time. Unfortunately, one would be in for a surprise…

But I digress. I think I mentioned it a couple posts ago, but the story behind this paper is that I was getting dangerously close to C student territory in my existential philo class after I failed to read most of the assigned texts (I was having a lot of difficulty concentrating—we were actually assigned really interesting stuff, I just didn't have the presence of mind to appreciate it at the time). So I decided I could probably get away with a pretty facile term paper if I could find some way to make it superficially amusing, and obviously fiction is the way to go. So somehow I convinced the professor to let me write this in lieu of the academic final:

Philosophy 336 Term Paper

The Existentialist

Whitney Robinson

Existentialism in its pure, intended form is liberating and beautiful…one lives simultaneously with conviction and with abandon: if nothing matters we are eternally free. Unfortunately, this insouciance is nearly impossible in a state of nature, and it all turns to giant cockroaches and visions of hell very quickly. The people who are drawn to existentialism are, with little exception, the ones most likely to be driven mad by it. To put it politely, they are slightly neurotic individuals, uncommonly bright but with a tendency to shred any tissue or bit of stray paper they are holding, to snappishly entreat people to define their terms in arguments.

Let us conjure a hypothetical existentialist: a college student, because the vast majority of those to whom existentialism appeals are that age; beyond then, one does not really want to pay such microscopic attention to one's own mind and the body it inhabits…both become increasingly unpleasant. Physically, we might imagine him (although it could just as easily be a her) as a slightly twitchy ectomorph, wearing stylishly unstylish glasses with chunky black frames, who neither washes nor cuts his hair quite often enough for comfort. To seal this image, he owns both a beret and a stocking cap, and wears one or the other of these regardless of the weather.

Although he reads philosophy, probably too much philosophy to be entirely healthy, this existentialist has no ambitions to be a philosopher, to create something new from the substratum. After all, 4.6 billion years of evolution have only been sufficient to produce one Kierkegaard. For a while he thought maybe he would just be a writer, that by writing beautifully he could make up for knowing nothing, but language itself became a series of problems. The most fundamental, of course, being the unproven nature of signifiers.

How do I know that red is red and blue is blue?

Maybe red is blue for me, and blue is red for you.

How do I know that I am me, and you are you?

Maybe we are illusions in a sucking vortex of eternal emptiness

And none of this is true.

But this is an elementary dilemma, a Philosophy 101 dilemma. It bores him that he finds it so compelling, and it sickens him that he is bored with a perfectly good paradox. At these times he often feels like biting something, so he eats. Because philosophy is psychology he knows that the veal cutlet is metaphorically his own skin, but then again, the baby cow and the man may not be ontologically distinct. No one can reduce themselves to a fetal ball of contradictions faster than an ailing philosopher, and our existentialist is sinking.

But he has a hope: pragmatism. It even considers itself philosophy, so it's not a total cop-out. Pragmatism assures him that he can put down Being and Time and go have a beer without turning into Nietzsche's pathetic Cheetoh-crunching, Jerry-Springer-watching Last Man. Relinquishing himself to his fallenness, to being-in-the-world, our existentialist decides to leave the problem of mind and prepare a quiche for dinner. Being a philosophy student, it logically follows that his refrigerator is empty, so we will meet up with him at Whole Foods, where he stands holding a list in front of a dazzling array of grocery products with only the simple missive 'eggs' to guide him. What does Kierkegaard have to say that might ease him through this dilemma? Surprisingly little, for someone who has produced many volumes of erudite prose. Existentialism tells us precious little about how to exist, but mostly takes perverse pleasure in telling us why we can't with any degree of tranquility. What use can philosophy be in helping a hungry existentialist choose the freshest eggs for his quiche? Now he understands why his father wanted him to be something useful like a mechanic or an electrician. These people might not be able to elucidate the Euthyphro dilemma, but they know how to survive.

And yet, how do you set it aside and say it doesn't matter? Doesn't one need to commit to one's philosophy? Among two millennia of eloquence there has been much talk of means-not-ends and philosopher kings, but our existentialist has found that philosophy is rather awkward anywhere but on paper or in minds. If all of philosophy is simply a series of parlor tricks for the woefully clever, why do we pretend it matters? Because pragmatism is a cop-out, he decides. He must find a way to make the elegant treatises he admires mean something in the world. But he is slightly afraid to even try to fuse Kierkegaard or Camus with egg selection; he uneasily remembers a prior shopping trip during his ethics seminar, when he was unable to decide between the organic and the conventional eggs, the one being more economical and the other more environmentally sound. He tried to apply the Categorical Imperative to this situation, uncertain of the potential ramifications of minimum-wage egg factory employees losing their jobs if no one bought conventional eggs. He tried to imagine a world where people only bought organic food, but he got confused somewhere along the way and ended up imagining himself as a giant talking chicken, which really freaked him out, and he decided that ethics had never been his strong suit. But he instinctively feels that animals should be treated respectfully if we're going to use their flesh and byproducts to sustain us, and that's enough for him.

If only all his cognitions were so effortless. He lacks instincts about the strangest things…sometimes he is like a kitten whose whiskers have been cut, leaving him bumping into mental walls that most people would avoid without thought. Now, for instance, people around him are plucking eggs unproblematically from the shelves, but there are at least a hundred individual cartons our existentialist could choose from. And if he opens himself to the possibility of a different supper entirely…the world is ablur with a riot of meat and vegetables vying for his attention. Suddenly his awareness of his own freedom is crushing, emetic. This phenomenon is so terrifying it has spawned its own pervasive form of angst, the kind associated with people exactly like him (at least three-quarters of whom also wear glasses with chunky black frames, irrespective of whether they need them). And still he has not chosen a carton of eggs. Maybe he should just skip the eggs altogether, and sup on milk from the carton and flour from the bag. Maybe he should just starve to death because he is too neurotic to live.

Dasein, Dasein, he chants internally to calm himself. Be cool. Be Dasein. His private mantra, which brings him peace. Actually, he is not quite sure what Dasein consists in, because it's one of those multifarious German words that doesn't translate well, but he remains careful to say 'consists in' rather than 'consists of', because this, along with the glasses, makes him seem like a real philosopher or at least a grad student.

Dasein. Why must he analyze everything to the bone? He wants so much to just be, to exist without introspection, to live the mindless, mercurial moment-to-moment life of the unexamined soul.

Perhaps he will buy some refreshing green tea to soothe his nerves. On the back of the box, he notices a Chinese proverb: 'Give thanks to the pot, for it gives up its emptiness for the tea.' Would but he could! In Eastern philosophy, emptiness is sacred. To achieve Nirvana is to extinguish, to lose the self forever. Yet how many of us can identify with that? In the Western world, emptiness is a dark void that fills us with unspeakable terror, which we try to fill with food and shoes and wireless technology commodities, and cling close to other people for comfort. Afraid that he is going to cry, and not wishing to do so in public, the existentialist hastily sets down the tea box and fumbles toward the dairy cooler. Steeling himself, he forces his eyes shut and gropes blindly until milk, eggs, cheese, and flour find their way into his cart. And then he stops at the bakery for some scones, because one can't be in a black existential quagmire for every second of every day.

And now comes a little relief for our tragic hero, because it's time to check out and he plays this game well. He carefully installs himself the checkout lane beside that of a lovely flaxen-haired young doe, so that when the lane closes, as he could see was imminent, he appears to be thrust into her presence by mere happenstance. Her gaze is calm and unperturbed as she scans the eggs, the milk, the flour…she knows nothing of the machinations that swirl around her innocent splendor. Bend a little lower over that bag of scones, dulcet minx…our existentialist has deliberately failed to label the bag with the corresponding bakery item code. As she rings up his purchase, the existentialist allows his eyes to make smoldering contact before flickering casually away to the magazine rack—but no, his eyes have landed on 'Home and Garden'. Now she will either assume he is gay or realize that his indifference is a façade. He manages to save the situation by grabbing a candy bar off a lower rack and pretending it was the attentional object all along. The candy bar has walnuts in it, which he hates, but the sweet sisters fate have made it right in the end, because the checkout girl's hand brushes his as she takes the candy bar to scan it. An electric thrill runs through his being as the tips of their fingers meet, and the girl's eyes flash momentarily up to his. He withdraws his hand quickly, the first of the two to retreat from contact, and utters a cool, polite "Thank you," just suggestive enough that she must later wonder if the tacit compliment was only in her imagination. Overcome as he reaches the door, our existentialist closes his eyes and loses himself to the aesthetic until people begin to look at him askance. He hastens out of the store, secretly smiling that this encounter has played out to perfection, and will sustain him for years to come.

Yet a scant hour later the bloom has faded from the rose. The world is open to him, chains of latent potentials leading to presidencies, riches, Nobel prizes…and yet he is eating a rather unsuccessful quiche alone in his apartment, and he does not delude himself into believing this will change, regardless of whether it can. He finds himself bitterly wishing he had sneered at the checkout girl, maybe made her self-conscious about her lowly position in society and slightly frizzy hair, which come to think of it looked like she dyed it anyway. He turns to the candy bar for solace, then remembers the walnuts…in addition to finding their taste unpleasant, they make his mouth itch. Sometimes, hypochondriacally, he wonders whether if he ate enough of them he would stop breathing. He toys with the idea in his darker moments. But for now, he merely stuffs some congealing quiche into his mouth and mutters aloud his ubiquitous though slightly borrowed catchphrase for all of life's failures, its cautionary gloom for all successes. "It doesn't matter", he tells himself, but he is not quite sure he believes it.

***

This might be unbearably sad, but we owe it to our existentialist to return to him twenty years later, to see him through to the end. Imagine him a little grayer but similarly attired, slouching into the Chestnut Tree Café, his habitual haunt at the outskirts of the university where he now resides as an eccentric faculty member whom the students quietly try to avoid.

"Afternoon, Winston," he murmurs to a hunched figure in the corner as he enters.

Taking his traditional seat, alone and mostly obscured from sight by a large potted plant, he sits quietly and broods in his search. Outside, idealistic liberal-arts majors chant for freedom in some impoverished country that everyone secretly wishes would just go away altogether. The students, and ones like them in bygones eras, have fought so hard for freedom, for the right to publicly declaim and disseminate their mindless mantra, and now they want to inflict the same liberty on others. Don't they know that men are happier as causal prisoners?

The students chant relentlessly on. Freedom, freedom, freedom! Our existentialist looks on with a tolerant, sickly smile. The silly students chase it like well-fed housecats enamored with a bright bird. On the off chance a claw catches in the feathers and brings the quarry down, they will be awed and frozen. When you have your freedom, what do you do with it? This is not part of the game. They will drop it and poke it gently with a puzzled paw, hoping it will fly away and the world will be right again. When the bird does not move, they will look guiltily around, hoping no one has witnessed them strike down teleology, then turn and slink away unsettled.

A waitress comes and asks our existentialist what she can bring him. Oh, cruel Pandora, you couldn't just have brought him a black coffee? How can you expect an existentialist to choose a dessert? The choice paralysis is astounding. In selecting the apple tart he may allow an orchard-keeper's daughter to attend college and in turn discover a cure for a disease that would have decimated the population…but perhaps this posited girl has darker ambitions, perhaps she will rise to political power and enact a regime that makes Red China look like Walden Two. Perhaps the orchard-keeper has no daughter, and apples are all grown in some kind of sterile facility these days. Maybe one pie bought or sold makes no difference to anyone's future, and then what is the point of eating it, save a sorry hedon or two for his personal satiety?

He could just as easily choose the coffee cake, but maybe it will contain traces of peanuts that will send him into sudden anaphylaxis. And perhaps if this occurs a lovely and talented young EMT will intubate him just in time, and he will find love at last. But this probability is slim at best, and the existentialist finds coffee cake to be rather dry and tasteless in general. He would suffer it for true love, but the chances of this are a barest fraction, and if he orders the chocolate pudding, which varies little from day to day, he will certainly be cozily sugar-sated for the rest of the afternoon…really, these momentary pleasures are all he can count on. On the other hand, he who lives without risk dies without glory…

Faced with the swirling, taunting, overwhelming possibilities, the existentialist will inevitably avert his eyes, point to something in blind panic, and end up choosing something he hates…probably something with walnuts or licorice. Over the years he has eaten many walnuts in similar straits. Perhaps this has been his undoing, along with the nights spent with heavy books perched on his solar plexus, with the choices examined to disintegration yet willed to be spontaneous. In the wrong hands, philosophy can make one very ill. The mind becomes diseased and scoliotic, head bowed and cervical vertebrae fused to direct a lidless, staring eye to the navel.

This is the fate befallen our poor existentialist, powerless to surrender his freedom. Either he will take up yoga, find a good chiropractor, and discover the many benefits of Eastern philosophy and/or anxiolytic drugs, or he will continue to skulk in dimly lit cafes, mumbling incoherently about the will to power and occasionally scribbling something in a notebook: an unreadably scholarly treatise, or a free-verse poem that fairly sears the page with incisive yet minimalist metaphor…the kind critics will love and no one will ever read. When the waitress brings his dessert, which in a truly sadistic exercise of culinary potentials contains both licorice and walnuts, the lonely existentialist can scarcely summon the energy to lift the sugary treat to his mouth. Utterly sick of his mind, he can hardly bear to nourish it through his body.

Freedom corrupts nearly as much as power, he reflects with an erudition that makes him want to smack himself upside the head…or rather, it corrodes, because human beings are contrary by nature; the very mind that leads us to the value of 'mere' existence will never allow us to live it in full. While the rest of the world seeks freedom, the existentialist seeks its cure. He has come to learn, as most agile-minded persons do, that consciousness is a disease, an itis of soul. As of yet, he has found no remedy, but he awaits death with interest.

And enlightenment spreads. As a contagion, it is more virulent than even panic or boy bands; sheer stupidity is the only known vaccine, but who would choose it? I tell you this as gently and decorously as I can, aware that you, reader, are free as well. The fourth wall cannot save you…it is too late to hastily set this down and pretend you were instead reading an interesting article on giraffes in National Geographic. If you have not already, you will soon realize that the whole world is choice, that every moment is a riot of potentialities to which we must blind ourselves. When some new paper in speculative astrophysics or applied neuroscience announces a certain proof of a closed causal chain, complete materialist determinism and the death of free will, you will read it with trembling anticipation, but in the end, you will realize it says nothing a few mental gymnastics cannot refute. Syllogism only works when you accept the singular if that leads to the unconditional then. But for the existentialist, the if is always surrounded by a million more, a swarm of tiny ant-like possibilities that together reduce a tree or a life to pulp in dismayingly short order. Freedom is one of those horrorfilm villains that never dies. In the unfortunate event that you stumble across it while cutting through some graveyard at night or wading too deeply into some arcane text, you will never be rid of it. And like the last attractive young person standing at the end, the obligatory lone survivor who knows the murdering masked marauder can never truly die, you will go insane. Only if you choose to go insane, of course. But you will.

***

We have closed this out with dismal style, but the story isn't over. The great philosopher lived for years in a walled asylum after setting his last cogent thoughts to paper. Any final fevered revelations were mumbled only to brisk, patronizing nurses or the flowers of a restful sanitarium garden. How much of our finest thought has been lost in the whispers of madmen?

Our existentialist has sunk into a similar entropy. Like Nietzsche, he has gone insane, but without having brought anything beautiful to the world. Indeed, he has begun to read the self-proclaimed Antichrist with a new appreciation, a rekindled willingness to look beneath the pomp and arrogance to find a man with answers instead of only questions. Someone who tells us we needn't disown life, however badly it abuses us. Beneath his stern mustache, his unwilling asceticism, his untimely psychosis, Nietzsche was a surprisingly hopeful sort of fellow, and our existentialist often seeks comfort in his prose at night. The futile grace of eternal recurrence alone is enough to bring meaning to a shattered world.

Send me your demon, Nietzsche! our existentialist prays in the dark, let me live every torturous moment of this finite world again. European to the core, he could not bear to extinguish in Nirvana. Should the blessed demon come and tell him his life will play out a billion billion times again without recollection, without a chance to learn from his mistakes, the existentialist will fall to his knees and cry thank you, thank you, divine creature. This is the beautiful taste in the bitterness, the redemption of the antihero. Life is unmeaning, which leaves us free to form it into anything we want…it exculpates us if we are not quite as successful as we had hoped, and humbles us if we are.

After all these years the existentialist still doesn't quite know what existentialism consists in, but he suspects he is closer to its center than he has ever been. We are bound by our circumstances and gagged by our genetics, and only our poor understanding of probability allows us to think we are special. And yet beneath this we are free, even to keep our eyes open or closed as the guillotine falls. Nothing you haven't said more beautifully, Sartre, nothing. The existentialist calls this aloud, although he has long ago realized the uselessness of passing ideas to others when all they do is make them their own. He will only ever stand in the shadows of great men, but this revelation belongs entirely to him, and again he cries aloud for the whole café or world to hear: I will take the suffering, I will take the angst. I will take the sleepless nights, the impenetrable prose, the walnuts in my cake. I am here and I am alive. I have been created, and that is enough.

July 1, 2011

Nature is a Temple

So I'd decided that for my next blog post I wanted to consider some Important Topic like free will and determinism, or the power of symbolic language to shape reality–something really heavy and existential. But in doing so I came to the conclusion that a., metaphysics is not my strong suit and b., thinking about such topics, and worse still trying to write about them, is highly unpleasant and stressful for me. I'm serious, it reduces me to a state of nervous anxiety. My stomach begins to churn, my hands go limp and icy, I develop an eerie farsighted stare and respond to conversational attempts with weak monosyllables. I am one of those people for whom philosophy is actually pathogenic.

Therefore, needing to calm my nerves after a traumatizing afternoon of considering Laplace's demon and the hard problem of consciousness, I went for a walk at the Arcadia Wildlife Sanctuary. There is something instantly soothing and reparative about the New England woods, which take on a different mood with every season but always manage to retain a certain mystique. There's a peculiar watchful quality about them, but it's not a malevolent presence. It's just that the spirit of nature feels very close. It always brings to mind a favorite quote by the Romantic poet Charles Baudelaire: "Nature is a temple in which living columns sometimes emit confused words. Man approaches it through forests of symbols, which observe him with familiar glances."

Evolutionary biologists argue that it's our unique human destiny to see meaning where meaning does not exist—to imagine faces in the moon and see weeping willows as sorrowful creatures because of the particular drape of their branches. But I wonder sometimes if these things really exist only in our minds, or if our perception of the 'inner life of objects' is in fact based upon something real. In the end, we know so little about the seething quantum forces that compose our world, or the laws that have drawn breath and dreams out of mere aggregates of chemicals. Who are we to say that trees have no souls? I should think they might reasonably believe the same of us…

June 23, 2011

agenttabbycat to kaleidopoet: you rock.

Today's post is dedicated to a close friend of mine. Actually, we're nothing like 'close' in the literal sense—he lives 2,000 miles away and I've never met him in person. Nonetheless, I've known him since he was 13 and I was 16, and he's of those rare people with whom one's camaraderie remains somehow outside of space and time, that does not decay with absence.

We first met on an young writer's forum online in 2002 or so. It was a rather cliquish group and contained some exceptionally talented young poets as well as a great deal of mediocre ones. Naturally, there was a lot of drama and backstabbing involved—as there will be in any group of teenagers and especially those with a literary bent—but in my mind it was one of the most formative settings of my teenage years, despite not being a physical 'place' at all.

In any case, the majority of us were depressed and socially awkward, so we spent an awful lot of time loitering about on AIM and talking to each other. Kind of a virtual coffee-house-a-la-Paris-1960 environment. We'd critique each other's work, collaborate on poems, rant about how we were misunderstood geniuses, etc. The site shut down when I was in my late teens, and the members gradually dispersed. I don't know what happened to most of the 'inner circle', but one became a lawyer and started his own young writer's site, one is a particularly talented singer, and another, I recently found out, is dead. I went to look him up on Facebook and found a link to his obituary.

But this particular young writer and I remained friends, although our correspondence mostly consists of an occasional Facebook chat or text message these days. Neither one of us had a smooth adolescence, to put it mildly (well, who does, I suppose), and it was kind of an inside joke between us, when talking after a protracted absence, to greet each other with a languid, "Oh, still alive, are you?" We remained very cool and ironic about it all, but there's no denying that what bound us was a profound and consuming despair.

At the risk of getting all sappy and annoying the hell out of him, I won't go on about how brilliant he is and how glad I am that he ended up not dying tragically. But he is, and I am. In fact, I'm going to call it now: this boy is going to do important things, and maybe someday I'll get to make a speech about how we once wrote elegant but undeniably melodramatic poems to each other at 2 a.m. in lieu of temporary or permanent acts of self-destruction.

Anyway, this week I found out that he's just received his Doctorate in Medicine at the age of 21. On learning this I was suffused with a pure, irrational joy. Happy for a friend, yes, but something more. I remember our assertions at age 14, 17, 19—just think, if we make it through these years alive, nothing's beyond us. We might become doctors, poets, bestselling authors. We never doubted our abilities, only our capacity to find peace within ourselves. Yet it seems that perhaps we have—nothing's certain, of course, but we've both accomplished what seemed like the faintest of theoretical probabilities, all those years ago, separated by a glowing screen, half a continent, and a lot of bleeding irony. He's a doctor, I'm soon to be a published author, and our brains have more or less stopped trying to kill us.

So, my dear, my incandescent mad polymath poet—congratulations. We played the hand biology dealt us, and it seems that we've won. You, in particular, have made biology your bitch. And biochemistry, and whatever other kind of chemistry there is, and physiology, and pharmacology…

June 17, 2011

Attack of the glistening obsidian algae

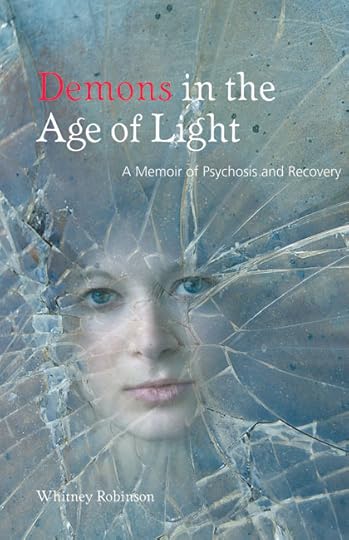

When DEMONS IN THE AGE OF LIGHT was being edited, it was pointed out to me that I have a tendency to over-use certain words in the manuscript. Namely, these were: strange, dark, ominous, black, void, translucent, glistening, algae, violent, abyss. (However I maintain that the sentence "The strange black ominous algae glistened translucently in the darkening void of the violent abyss" does not appear once). It made me think…do the words that crop up a little too often in our written work reveal something about our soul? If so, I may be in trouble…

Actually, that list of words reminds me strikingly of the poems I used to write when I was a teenager. You know, the kind everyone writes at 2 a.m. as a substitute or accompaniment to minor acts of self-mutilation. Except I'm gratified to note that I managed to avoid using the word 'obsidian' anywhere in DEMONS—it was a particular word-fetish of mine when I was fifteen. You know, obsidian butterflies, obsidian tears, obsidian porcupines…obsidian made everything 20% cooler. I think—I hope—that overall, my prose has improved somewhat in the past 8 years, but it seems the remnants of my teenage angst still linger in the darker (violent, glistening…) corners of my writing.

[Look, my seventeen-year-old self is filled with so much ennui

that she has literally turned blue].

June 8, 2011

Verbose Russian Absorbs Most of My Summer

So lately I've been feeling guilty about all the Great Literature that I haven't read. Partly this is inevitable because there is just too much of it. I'm not sure if it's even possible to be thoroughly 'literate' anymore, much as it becomes increasingly difficult for young doctors to absorb a broad foundation in medicine. Each specialty simply contains too much information for the human mind to retain. Likewise there are only so many books one can read in a given lifetime, yet the total volume of literature in the world multiplies exponentially. It also doesn't help that the average young adult brain is no longer wired to sit down for three or four cozy hours of Proust or what have you. At least mine isn't. I've always had difficulty with reading and sustained attention—I don't think I can blame the Internet either because I was like that from the time I was a kid and preteens didn't have iPads back then, because they didn't exist. I wasn't even allowed to watch much television (although at age 9 I staged a hunger strike until I was allowed to watch the X-Files).

Later, in college, I had a regrettable tendency to write my papers based on secondhand Internet research rather than actually cracking a book. A basic grasp of the English language and a few clever stock phrases will get you a long, long way in an undergrad liberal arts class. I was only caught out once, by my existential philosophy professor, who later asked me on a date, but I digress. The book was "Siddhartha" and I started to read an online plot summary but got distracted by funny cat pictures or something and ended up writing the paper based on 78% of a Wikipedia article (yes, I swear upon Being and Time, I was THAT lazy). My vague conjecture about how the book ended was totally wrong, and it turns out that professors sometimes do read student papers in their entirety.

C-, and I probably only got an A for the course because I managed to finagle the professor into letting me write "a work of existential fiction" in lieu of my final essay. I wrote a rather charming (if I do say) piece about a philosophy grad student (more or less based on my professor) who had an existential crisis while shopping for quiche ingredients at Whole Foods. The lesson I learned from this experience was: Don't write papers based upon neither a book nor its summary, and secondly: At the end of the day it doesn't matter whether you can read if you can write.

The funny thing is, I actually read Siddhartha after the course was over (perversely, I waited until I had received my diploma to read the majority of my assigned texts. I mean, who wants to read a book that you're going to be tested on?) and it ended up becoming one of my favorite books.

Anyway, this is a roundabout way of saying that I've decided to patch at least one small gap in my literary education. I decided to choose one Great Author to read in his or her entirety this summer. Thus, my goal is to have read, by the end of August, every published novel and short story of Vladimir Nabokov. All told I am estimating that this will shave about 250-300 hours from my summer, depending on my reading speed–about two weeks straight if I choose not to sleep or eat during this period, but I'm not quite that devoted. I picked Nabokov because he's impressively literary but actually fun to read as well, and even his more meandering and experimental novels sparkle with his exquisite prose gems: "..". And, most significantly, he hasn't produced any monster 3000-page opuses like certain other authors *cough Proust cough* that I considered. Also, being mostly Russian on my father's side, I was inclined to choose an author of that lineage.

Unfortunately I'm no English major so most of the literary devices and cultural references go whooshing over my head (not to mention that dear V.N. assumes working knowledge of idiomatic French and Russian). But at least I feel all virtuous and stuff, like I'm repairing some of the brain damage inflicted by lolcats, textsfromlastnight, Charlie the Unicorn, and other perils of the age. Actually I'm probably dating myself here—I bet kids today don't even remember Charlie the Unicorn (however I found a Charlie the Unicorn t-shirt in a thrift shop recently and needless to say I squealed like a trodden baby mammal and immediately coughed up the $3 for its purchase).

But right, Nabokov. So far I've finished Lolita; Speak, Memory; Transparent Things; Glory; The Eye; Mary; Despair; Invitation to a Beheading; Pnin; Ada and Look at the Harlequins. I think that leaves nine to go and 65 short stories (!), and possibly a play or two. I suck at novelic analysis so I will spare you my interpretations of said texts (from what I gather Nabokov was contemptuous of comparative literature anyway), but suffice it to say I can feel new neurons forming in my somewhat cobwebbed brain with every page. Maybe it will even induce me to write something—I'd dearly like to be a novelist, but at times I'm afraid my brain can't or won't work with enough efficiency and organization to pull it off. More on that later. Now, Bend Sinister.

June 6, 2011

The Peculiar Serenity of Abandoned Places

I'm hardly an urban explorer of opacity caliber, but from time to time I do love a good romp in a derelict building. A while ago I got to explore an old egg carton factory as it was in the process of being stripped for copper wire. There is something primal about crunching over glass and pigeon feathers with silent industrial-age assembly lines rusting in the broken beams of sun filtering through a boarded window. Your senses sharpen—the scuffle of mice and the creak of rotting wood and warped sheet metal are strangely amplified, and you can practically taste the mold and asbestos dust in the air. You begin to feel like a character in a post-apocalyptic novel, ready to start harpooning rats and barricading the doors of a defunct office against the inevitable midnight zombie attack. The mind slips all too easily into the fantasy, and when you leave you're almost disappointed that the highways and gas stations and supermarkets are still well lit and stocked with every amenity, still awaiting Armageddon. Well, I suppose it's only a matter of time, but it's easy to dream darkly among the paradoxical beauty and ugliness of civilization's inevitable decay.

June 3, 2011

Label Me Like A Surf Hollister Mannequin

So, returning to the idea of labels and mental illness.

One might say that two principles are in opposition here: the desire to individuate and the desire to belong. In high school this manifests mostly in the form of fashion angst–one tries to be unique within a closed system of acceptable accessories and couture. In the realm of psychiatry (which often follows logically from "the realm of high school" haha), the stakes are a bit higher. Naturally any time someone is labeled as "mentally ill", this creates a dangerous potential for a self-perpetuating prophecy. Indeed, many clinicians don't focus on diagnostic labels, preferring to treat the person more organically as a whole, with respect to culture, environmental stressors, and global strengths and weaknesses. Unfortunately this tends not to be the case in the treatment of disorders involving altered perceptions—e.g. hallucinations, delusions. These symptoms are so striking that it can be hard to get past them to consider other factors of an individual's personality and environment. When I was being treated, I was told in no unclear terms that I was schizophrenic and this condition would remain with me for the rest of my life. Although I naturally rebelled against this rather presumptive declaration, there was also something comforting in it, knowing that people would always be looking out for me, that I was not alone.

In any case, I don't object to labels like psychosis, schizophrenia, and mental illness, simply because there are no terms outside the realm of psychology that capture the interplay of biological, spiritual, and social factors that combine to form any ego-dystonic experience. Indeed I've always found schizophrenia to be a rather eloquent word, etymologically: a shattered mind, a schism of the self. It's an accurate description. The real problem lies in the fact that there are so few reliable treatments for it, whatever it is. Personally I received little benefit from antipsychotic drugs, and I tried many of them. I think that at the core of my experience was a schism of identity so deep that merely muffling the auditory manifestations of this crisis was insufficient to produce peace or healing. Indeed these drugs produced such a profound sense of loss—I no longer felt kind of emotion, positive or negative—that I couldn't bear the silence it engendered. I still felt as if my body was being sucked atom by atom into an abyss. A number of people I've known have had similar experiences, yet others seem to do just fine with them. It's sort of hard for me to believe—"like seriously? You don't feel like your soul is being sucked out of your nostrils with every breath?" but I don't want to fall into the fallacy of making grand scale statements about the evils of antipsychotic drugs simply because my experience was so bad. However, I eventually came to the conclusion that mine was a spiritual crisis, albeit perhaps bestowed by genetics or other biological destiny, and that any lasting cure would have to target the soul directly, the spirit—terms which at that time I regarded with a kind of wistful skepticism. I'd been raised Christian but like most disaffected young people, adopted a more materialistic worldview in my teens. I ended up trying a number of alternative healing modalities, some of which are described into my book, which I'll describe in more detail in a future post.

The medical model, of course, views schizophrenia as a purely biological, neurochemical malfunction, a combination of susceptible genes and environmental stressors. On the opposite end of the spectrum, New-Agey types view psychotic experiences as a rite of passage that many spiritually inclined people must endure as a result of past lives or an uncommon sensitivity to the chaotic energies that abound in the world. In energetic terms, the third eye chakra is too open, inviting an excess of reality, a surfeit of meaning. In clinical depression, one's life may seem to lack all meaning. At the core of psychotic experiences lies its opposite—meaning multiplies beyond all necessity. Signs and symbols turn on the minds that created them, become cancerous and pervasive. Everything has significance, every interpretation is laced with doubt.

However I want to object to the idea that schizophrenia is purely a visionary state. It's really not that romantic. Many people experience visionary or spiritual events that are outside the realm of accepted reality, but they don't usually end up in psychiatric hospitals. Most disorders in the DSM-IV that are predicated on the fact that the individual is experiencing significant, life altering distress as a result of his or her symptoms). I think that many people with major mental illnesses possess the intrinsic qualities of a visionary (uncommon levels of insight and perception) but psychosis itself is not equivalent to enlightenment. More information is coming at us, but it's not necessarily better or more true information. Indeed, the devil loves complexity. In all likelihood the medical explanation and the spiritual one meet in some demilitarized zone we haven't yet found the words or science for. A dull compromise, I suppose—maybe I should think of something more heretical to say. Or maybe my belief that I have a soul and that it may fall into danger or grace depending on my actions is enough, in this particular zeitgeist, to make me an iconoclast.

May 21, 2011

A Beginning

Oddly enough I found that writing this first post induced more writer's block than starting an actual novel. At least if you're beginning a book you have an idea, a baseline, a vague conception of where all this is headed. Essentially I am writing this blog because my publisher said, "Whitney, you should start a blog so people will have some idea of who you are". And I was like, "But I'm a really random person, I don't have an agenda or ideology worthy of a cohesive blog, nor do I draw amusing webcomics". And they said, "Random is fine as long as you're mildly entertaining. We have confidence in you."

And I agreed I could probably do that, but the idea of a blog in which I express myself outside the safe and finite structure of a book forced me to think about what exactly I want to stand for. I don't want to be one of those people who talks despite having nothing to say. I don't want to be so postmodern that I refuse to take any ideological stance on issues that matter to me. The most personally relevant, of course, is the idea of mental illness. Do I want to identify with my diagnosis or not? Do I want to challenge the entire system in which I am soon to receive my graduate training? And then I have to confront the issue I've been carefully trying to repress for the three months prior to the release of my memoir, namely the possibility that publishing it could harm—actually 'destroy' was the word I initially conjured, and then 'decimate' until I remembered that it means destroy 10% of something, not all of it (thank you, Barron's GRE prep!) my career prospects in the field of psychology.

And then I decided I was being melodramatic, but I can't be sure. There are a number of prominent psychologists, lawyers, and doctors who've written about their experiences with mental illness, but on the other hand I really, really lost it for a while, with 'it' being my entire subjective sense of self. Furthermore I'm not even established in my field, I'm a sparkling new graduate student. I don't know if the 'get out of the locker room, freak…' mentality will transfer from high school into a professional, academic setting. I wouldn't be applying to these programs if I doubted my ability to be both professional and academic, but I can't say with certainty that I will never experience another psychotic episode—although really, who can?—and I don't know if I'm ready to be a voice in a new generation of people who've had serious breakdowns at a young age (there are a lot of us, more than you might think) and are now trying to become professional adults acting in the elusive and perhaps illusive Real World.

I don't know to what degree I want to challenge the system in which I've seen, firsthand, so many flaws, but mostly people with good intentions trying to do their best within a cumbersome bureaucracy. I've always had a vague suspicion of people who criticize what they don't intend to change. This is why I don't care if people call me schizophrenic—the category may be poorly conceived but I don't think challenging the semantics is going to do much to change the reality. I'll return to this topic soon, but for now I'll end this post with an excerpt from Demons in the Age of Light:

Chapter Nine

I first become aware of my breathing—it is deep and regular, under the competent care of my autonomic nervous system. When I try to take over it becomes erratic, desperate, thinking I need more oxygen when really I don't. My eyes open and see too much white. My head is too heavy to lift, but moving my eyes I can see a corner of the room at a time. Monitors in one corner, silent and unlit. My parents in two chairs along the wall, heads bowed and hands limply resting in their laps. My eyes drift closed again.

Someone comes in and jabs me with a needle. I swear reflexively and my parents jump up and hover near the bed. "Whitney?" says my mother cautiously, as if she is afraid I will not know my own name.

I shift in the bed and a jolt of pain radiates across the back of my hand. I look down and see my arm covered in a pillowy bandage.

"You tried to kill yourself," says the needle-jabber, a nurse in a flowery scrub shirt, in a disapproving tone. How insular to assume it was suicide and not murder. My body feels heavy and adrift, my vision creating blurry haloes around everything. For a moment I wonder if I somehow exorcised the Other, bled him out like snake venom. But with a crushing awareness I feel his consciousness superimposed on mine again, a neutral crimson plane that reveals nothing.

What did you do to me. What…

His presence is serene and melodic again, like the reading of a haiku.

Nothing at all…

it seems even shy soma thinks you're better off dead,

though she could not say it to your face.

"What happened, Whitney?" asks my mother. "Why did you do this?"

"I didn't. It was…" But the truth is impossible, and I am too weary to come up with a plausible decoy. "A mistake," I say finally. "Just a mistake."

"We'd like you to stay in the hospital until we feel that you're no longer a danger to yourself," says the nurse. "Someone will be here soon shortly to bring you upstairs."

"Upstairs?"

"To our psychiatric facility."

"A psych ward? No thanks."

"Ah, well…" she says delicately, and I realize the insinuation that I have a choice was only politeness. The nurse slides a consent form into my hand. From his comfortable perch in my mind the Other says nothing, but the silence is suffused with bright, sinister interest as he waits to see what I will make of the situation. I click the pen a few times, indecisively. The nurse's eyes take on a strange apprehension, and I realize that it's a ballpoint pen and she was probably supposed to give me a felt-tipped pen and she's worried I'm going to stab myself in the jugular and bleed out and die or sue the hospital or both. If it weren't for my parents I might have given her a little scare, but they're watching with that rabbit-in-the-headlights look so I just sign the paper and give her the pen.

Soon two ER techs come in and wheel me down a hall full of people resting doll-like in white beds, then into an elevator that seems to go up for a long time. I have heard that psych wards are always on the top floor to minimize the possibility of escape. My parents have gone up by another way and are waiting in front of the ward door, a steel contraption with a reinforced window that looks like it could survive a bomb. It makes a buzzing noise and opens admit me. Someone tells my parents that they will have to leave now, but visiting hours are six to eight on weekdays and two to six on weekends. My parents look glazed. They tell me they love me. But I can't say it back…he is listening, and anything I value he will turn into collateral. So I just nod and hope they see it in my eyes.

***

The psych ward looks like you'd expect from movies and books, except a little more airport lobby and not quite so Kafka; droning TV overlooked by a plexiglass-fronted nurse's station, faded people sitting unnaturally still on faded couches. But when I look closer they are not still at all. Limbs twitch, feet tap, fingers shred tissues into a fine confetti. The impression of stillness comes only from the faces, which have a curious blank, oily sheen. Only a black girl with a red scarf over her hair returns my gaze with interest. There is something like a challenge in her face, although I don't know why. We stare at each other from across the room like unfamiliar cats angling for dominance. After a minute she smiles mysteriously and presses a finger to her lips in a silent shhhh before turning back to the television.

The ER techs help me into a chair in front of the nurse's station and wheel the empty bed back out of the ward. A few patients shuffle over with a strange zombielike gait. "Who're you?" says an old man in a peculiar snuffling voice. He is wearing a hospital gown like an overcoat, the strings knotted over his bare emaciated chest. His teeth are very bad. I do not particularly want to tell him my name, so I stare vaguely over his shoulder and feign deafness.

"Who're you?" he repeats, stepping closer. "I said who're you?" He breathes a sour chemical smell on me. The other patient, a fat woman with a tangle of dark unbrushed hair, reaches out and touches my shirtsleeve, rolling the fabric between thumb and forefinger as if testing the quality. The man holds out a sticky plastic cup full of yellow chunks.

"HAVE SOME PINEAPPLE," he says in a terrible, thundering, godlike voice.

I shrink back in my chair. If I keep still maybe he will leave me alone, or maybe he will be angry if I don't take it…

What's the matter? Don't you like your new friends? I flinch as the Other erupts into consciousness like an unexpected surge of static from a dead radio station.

A nurse comes out from behind the glass barrier. "Patricia…Anton…stop bothering her." She flicks her hands as if shooing away a couple of stray cats. They retreat a few reluctant paces and watch as the nurse takes my blood pressure, breathing deeply and rhythmically through their mouths like someone sleeping with a head cold.

"This is intramuscular haloperidol," says the nurse beside me. "I'm going to inject it into your arm, okay?" A sting near my shoulder, and within minutes a foggy paralytic haze has crept over my mind, sealing out every thought regardless of origin.

Someone propels me to a room and I stretch out on a hard white bed. To have a drug encamped in one's brain is not so wrong as having another ego there. It acts with no malice, no free will. I close my eyes and am not so sad to have lost my mind. If I can't have it, no one should.

Whitney Robinson's Blog

- Whitney Robinson's profile

- 6 followers