Billy Coffey's Blog, page 45

December 14, 2011

Looking for Jesus

The thing about living at the foot of a mountain is that it's often windy. Sometimes it's little more than a gentle breeze that will tousle your hair. Other times it's enough to make you pull your ball cap down a little tighter. And then there are the winds that don't simply blow but rage. Like the ones last Wednesday.

The thing about living at the foot of a mountain is that it's often windy. Sometimes it's little more than a gentle breeze that will tousle your hair. Other times it's enough to make you pull your ball cap down a little tighter. And then there are the winds that don't simply blow but rage. Like the ones last Wednesday.

I was outside the next morning surveying the damage, which wasn't all together bad. The only things out of place were a few of the Christmas decorations—two bows that had found their way into the rose bushes, a strand of lights that had been blown from the tree, and a toppled Nativity scene.

The bows and lights were simple enough, though I had to impale my thumb on a thorn and smack myself in the face with a tree branch in order to set aright what the wind had blown askew. Mary, Joseph, a wise man, and a shepherd had dog piled the holy child to shield him from harm.

I stood the shepherd up first, brushing away a few leaves and a clump of mud. Then the wise man, then Joseph, and finally Mary. Then I stooped down to brush off little Emmanuel.

Halfway into my crouch, I stopped. In a strange act of contortion I didn't believe was possible, I both furrowed my brow and bulged my eyes at the sight before me. Because there, right there where the swaddled babe was supposed to be, was nothing.

The rusty gears in my head began to lurch and churn, the results of which seemed to be subtle variations of one question—And what's that mean?

And what's that mean? The dog pile didn't work.

And what's that mean? My Baby Jesus is gone.

And what's that mean? Uh-oh.

I stood up and looked around. Nothing. Looked under the truck and around the corner of the house and in the neighbor's yard and by the creek. Nothing.

A chill ran down my spine that could have either been panic or the last remnants of the cold December wind the night before. How could we have Christmas without the Baby Jesus? What now?

I entertained a brief thought that I should call in and take the day off ("Jesus is MISSING!" I would say). But I didn't. I wasn't worried. After all, I'd found the real one. Surely I could find a plastic one, too.

Surely. Maybe. Well, hopefully.

I didn't get much done that day; I was paid more for eight hours of worry and dread than actual work. My children were ignorant of the situation for obvious reasons. A missing Baby Jesus would bring the sort of panic that children display in tears and snot. Which meant I would have to find him before they knew he was missing.

I went home that afternoon and searched the entire neighborhood. I knocked on doors ("Have you found Jesus?" I asked, and received many wonderful answers. And one that was not so wonderful). I made phone calls. I drove, and when that didn't work I walked. I even resorted to calling out His name—"Jesus?" "JESUS??"

Still? Nothing.

I had given up and begun preparing my failed-father speech to the family when I spotted a hunk of plastic beneath an evergreen tree. I'd be lying if I said there was a golden ray of light shining down upon it, but it sure felt that way. I sprinted over to the tree, pulled back a dangling branch, and lo and behold, there he lay in peaceful plastic slumber.

My Baby Jesus is back where he belongs now, safely tucked just under the living room window with ma and pa watching over him. And also two carefully placed stakes holding him in place.

I just checked on him. Still there. But a thought came to my mind as I peered through the curtains—shouldn't I be more mindful of where the real Jesus is than my plastic one? Shouldn't I make sure that He, too, is right beside me? And in those times when I find He isn't, shouldn't I go looking for Him with the same sense of purpose and urgency that I did with a simple Christmas decoration?

Yes, I think. Very much so.

Because the winds rage not just outside my window, but inside my heart, too. They howl doubt and blow jealousy. They gust fear. And while those winds can never blow Jesus away from me, they've been known upon occasion to blow me away from Him.

Share and Enjoy:

December 12, 2011

Faith and fear

image courtesy of photobucket.com

I knew sleep wouldn't come for me when my wife said, "Your face is melting."

It came easy enough for her—she rolled over right and was gone in seconds, before I could even reply. Which I suppose was a good thing. How could I have responded to that? The only thing I could have said was roll over and get some sleep, which she did.

It's unsettling to hear something like that from an otherwise rational person—"Your face is melting." And it's downright fearful when it comes from someone who only hours before had been in surgery to have an organ removed.

Thanks to modern medicine, these days few patients actually stay overnight in the hospital. I learned that today. I also learned that the things doctors and nurses tell you when you're taking that patient home can scare the living bejesus out of you. They said to watch for leakage from her bandages, cautioned me not to let her toss about in bed, said there would be pain and a bit of mental discombobulation. They did not say it would appear to her that my face is melting.

So I knew sleep wouldn't come. And now, four hours later, it still hasn't.

A lack of weariness has little to do with why I'm still awake. I'm tired. And I'm not still awake because I need to make sure she's still breathing, even though that's what I'm doing. I know that sounds ridiculous, but in those small hours of the night what is ridiculous has a funny way of becoming what is important.

No, I'm awake because I'm afraid. Pure and simple. And just as being afraid is a choice, so too is my decision not to sleep.

I will be awake all night. That isn't a problem. I'm a writer and a father; sleepless nights go with the territory. I have a pot of coffee in the kitchen, some chapters to edit, and reruns of Frasier on the television. I'm set.

I've prayed. I think there's a validity to the notion that God hears the prayers of the desperate a little clearer than anyone else's, if only because those supplications spring forth from a sense of helplessness and humility. I prayed that there would be no leakage, that she would not toss, that her pain would go away and that she would not get sicker. But those words tasted like pennies in my mouth. I suppose that's a symptom of fear as well—when you pray, it's not to ask for good things to happen but to ask that bad things won't.

She's still breathing, still keeping still. Frasier has just lost yet another in a long line of loves. That he did so in a humorous way doesn't make me laugh as it usually does. I just see his loneliness and know what a powerful thing that is, and I know that life isn't the bulwark we make it to be. It is fragile and can be snatched away at any time, and that is why I am afraid. It is a choice that does not feel like a choice.

The problem is that I want to sleep. I want to close my eyes right now and wake in the morning to find I've stopped writing mid-sentence, because then I will know that I chose faith over fear. That I let God and his angels tend to my wife and not my worry.

But I can't.

My son said this evening that he's happy his mother his home. He said there are angels here. He's seen them. He's said once he even heard one. He said the angel didn't talk so much as sing, and that it sounded like a wave pulling back into the ocean over a million tiny shells.

I wish I could hear that song now.

Maybe I can. Maybe I just have to sit here and listen hard enough. Maybe the point isn't to never feel fear, but to see fear for what it is: the large shadow of a tiny thing.

Maybe it's enough to know the angels are here and God is here and—

Share and Enjoy:

December 7, 2011

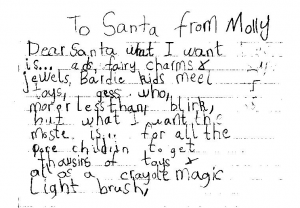

Dear Santa

My daughter's letter to Santa. A little fuzzy, I know. But appropriate since I'm feeling a little fuzzy at the moment myself. The fairy charms and jewels and the Guess Who? game are hidden in the attic, along with a few other things that will come as a pleasant surprise to her on Christmas morning. But what she wants most, for all the children to get thousands of toys? Well, that's a little more than this Santa can deliver. Funny, though, that she thinks every child should get a set of Crayolas. I think that's a good idea. The world needs more color. I remember asking Santa for a set of Crayolas. The big box of ninety-six with the sharpener in the back. Got it, too. I wrote a letter to Santa every year until I was nine, when The Dreaded Truth finally came to light. After that, my annual wish list was devoid of carefully planned sentences and colored pictures at the bottom of Christmas trees and elves. Instead, it came in the form of a few scribbles on scrap paper that I handed to my mother. But the magic of Christmas that was gone then is back now, though in another, purer form. My thoughts this year aren't focused upon what I want or even what the kids want. They seem deeper somehow. Better, too. My son asked me this morning if I had written my letter to Santa. I told him no, that only kids write letters. "Grownups are old enough to take care of themselves," I said. He thought about that, and then said that nobody can really take care of themselves and that the Bible said so. He had a point. So we sat at the table together, trying to figure out what I wanted and what I really didn't. The result: Dear Santa, Hello from Billy. I know it's been a while since I've written you, but I'm hoping you understand. And there have been times when I really wasn't a very good boy, but I'm hoping you understand that, too. It is with full clarity of mind that I wish for no presents this year. I wish my stocking empty and my customary place beneath the tree bare. I do not need gifts that can be purchased from catalogs or shopping malls. They will not make me a better man, a better husband, or a better father. Instead, I merely ask for another year of what I have received my entire life. I ask for love to accept my imperfections and failures, not through excuse, but through the understanding that no matter how horribly I may act, there is not a day that begins without my solemn vow to make it a better one than the day before. I ask for companionship in those days of drear (of which I am sure there will be many) as well as those days of cheer (of which I hope there will be just as many). I ask for faith to push me forward when I wish to turn away, to never surrender to the poisons of doubt and despair, and to convince me that God would rather lose His Son than lose me. I ask for hope to give me the strength to see the world in all its cruelty and injustice and still believe that in the end good will triumph over evil, right will overcome wrong, and peace will reign forever more. Lastly, I ask for the magic to believe that the spirit of Christmas can be found throughout the year, that the giving and sharing of our blessings and our lives draw us not only nearer to one another, but nearer to God, and that miracles and angels abound every day. Love. Companionship. Faith. Hope. Magic. These are My Wishes for this year. Gifts that require the opening of hearts rather than checkbooks. Gifts intended for us all, given freely on that first Christmas two thousand years ago, wrapped in swaddling clothes and lying in a manger. Hope to see you soon, Billy

My daughter's letter to Santa. A little fuzzy, I know. But appropriate since I'm feeling a little fuzzy at the moment myself. The fairy charms and jewels and the Guess Who? game are hidden in the attic, along with a few other things that will come as a pleasant surprise to her on Christmas morning. But what she wants most, for all the children to get thousands of toys? Well, that's a little more than this Santa can deliver. Funny, though, that she thinks every child should get a set of Crayolas. I think that's a good idea. The world needs more color. I remember asking Santa for a set of Crayolas. The big box of ninety-six with the sharpener in the back. Got it, too. I wrote a letter to Santa every year until I was nine, when The Dreaded Truth finally came to light. After that, my annual wish list was devoid of carefully planned sentences and colored pictures at the bottom of Christmas trees and elves. Instead, it came in the form of a few scribbles on scrap paper that I handed to my mother. But the magic of Christmas that was gone then is back now, though in another, purer form. My thoughts this year aren't focused upon what I want or even what the kids want. They seem deeper somehow. Better, too. My son asked me this morning if I had written my letter to Santa. I told him no, that only kids write letters. "Grownups are old enough to take care of themselves," I said. He thought about that, and then said that nobody can really take care of themselves and that the Bible said so. He had a point. So we sat at the table together, trying to figure out what I wanted and what I really didn't. The result: Dear Santa, Hello from Billy. I know it's been a while since I've written you, but I'm hoping you understand. And there have been times when I really wasn't a very good boy, but I'm hoping you understand that, too. It is with full clarity of mind that I wish for no presents this year. I wish my stocking empty and my customary place beneath the tree bare. I do not need gifts that can be purchased from catalogs or shopping malls. They will not make me a better man, a better husband, or a better father. Instead, I merely ask for another year of what I have received my entire life. I ask for love to accept my imperfections and failures, not through excuse, but through the understanding that no matter how horribly I may act, there is not a day that begins without my solemn vow to make it a better one than the day before. I ask for companionship in those days of drear (of which I am sure there will be many) as well as those days of cheer (of which I hope there will be just as many). I ask for faith to push me forward when I wish to turn away, to never surrender to the poisons of doubt and despair, and to convince me that God would rather lose His Son than lose me. I ask for hope to give me the strength to see the world in all its cruelty and injustice and still believe that in the end good will triumph over evil, right will overcome wrong, and peace will reign forever more. Lastly, I ask for the magic to believe that the spirit of Christmas can be found throughout the year, that the giving and sharing of our blessings and our lives draw us not only nearer to one another, but nearer to God, and that miracles and angels abound every day. Love. Companionship. Faith. Hope. Magic. These are My Wishes for this year. Gifts that require the opening of hearts rather than checkbooks. Gifts intended for us all, given freely on that first Christmas two thousand years ago, wrapped in swaddling clothes and lying in a manger. Hope to see you soon, Billy

Share and Enjoy:

December 5, 2011

The wandering wise man

What you see to the right is the last remnants of the Coffey family's most cherished Christmas tradition—the Wandering Wise Man. Dropped earlier this afternoon by two very excited hands and onto the ceramic tile of the bathroom floor. May he rest in pieces.

What you see to the right is the last remnants of the Coffey family's most cherished Christmas tradition—the Wandering Wise Man. Dropped earlier this afternoon by two very excited hands and onto the ceramic tile of the bathroom floor. May he rest in pieces.

In order for me to fully explain the enormity of this event, I need to tell you about before. About three Christmases ago, when we were unpacking lights and ornaments and garland. And, most importantly, our manger scene.

My daughter was the self-appointed Nativity Setter-Upper, and it was a task she approached with the utmost holiness and care. Animals were positioned first, then shepherds and angels, Mary and Joseph, and then Baby Jesus. The wise men came last. Three of them usually.

But that year, there were only two.

We rooted through boxes and overturned ottomans and scoured the dark places beneath the television stand. Nothing. Which meant Daddy had to climb back into the attic with a flashlight and a prayer. Both worked. I found him upside down and backwards in a corner guarded by a hairy-looking spider. Problem solved.

But then a thought occurred to me. One about how we all seek Christ but sometimes get turned around and lost, and how it's important to keep looking anyway. I put the wise man in my pocket, walked downstairs, and said nothing.

A while later my son happened to walk down the hallway and see the wise man in the middle of the floor along with a note—Have you seen Baby Jesus? By the time he ran back into the living room to summon the rest of the family, it had moved again. This time to my daughter's bedroom.

"Guess he fell out of the box when we put the Nativity back in the attic last year," I said. "Now he's gotta find Jesus before Christmas."

Thus the Wandering Wise Man was born.

He has miraculously emerged every year since in the weeks before Christmas, moving daily—often more than once—from room to room in search of the Savior. It is as far as I can tell the best idea I've ever had. The kids are so engrossed in his progress that come Christmas morning they head to the Nativity first and the tree second, just to make sure he's reached his destination.

Earlier tonight the wise man appeared by the sink in the bathroom, where he was found by my daughter. In her excitement to spread the news, she knocked the figure to the floor. He shattered into a hundred pieces.

She did, too.

I found her on the bathroom floor cupping as many shards as she could find into her hand.

"I broke the wise man," she sobbed. "I ruined everything!"

Uh-oh.

I gathered her off the floor and passed her to my wife, who took her to the living room for some rocking chair therapy. I snuck away long enough to swipe another wise man from the Nativity, scribble a new note, and place both at her bedside.

She found them a while later. Christmas was saved.

I checked in on her a bit ago before heading off to bed. Beside the wise man was a note written in seven-year-old scribble:

Dear 2nd wiseman thank you for showing up. I'm so sorry for hurting your friend.

I smiled. Both at the words and the little girl who wrote them. Then I took a pen from my pocket, turned the note over, and wrote a reply:

Please don't be upset. Everyone makes mistakes. We'll always love you, the wise men.

I'm pretty sure that note won't mend her broken heart, but it might be enough to get the needle and thread going. Sometimes that's all you can hope for.

Because the lessons that count the most also tend to hurt the most. Lessons like the one my daughter learned today. No matter how careful we are, we still break stuff. And not just wise men. Hearts, promises, trust, and dreams, too.

No matter how hard we try, we still make a mess sometimes. We still shatter the sacred and the special, leaving nothing but the shards of what was once whole that we're forced to pick up through our tears.

Thankfully, the One whom the wise men seek doesn't believe in everything being ruined. He's in the business of putting together and making new.

And like my daughter's wise men, He'll always love us.

Share and Enjoy:

November 30, 2011

The Why and the What

image courtesy of photobucket.com

If you've been around here for very long, chances are you've caught me discussing my daughter's diabetes. Talking about it, wrestling with it, trying to find the reasons behind it or trying to find out if there's a reason at all. It's one of those things that can be tough to figure out if you subscribe to the idea of a loving God.

To say my daughter's disease is a part of His will leaves a bad taste in my mouth (it's metallic, that taste, like having pennies in your cheeks).

To say that it's meant as a blessing tastes even worse. Come stay with her for a couple days and see if you can say that. You might still be able to, but I bet you won't be able to look me in the eye.

But to say that there isn't a reason at all, that it's just one of those things because life just kind of sucks sometimes, doesn't really sit well either. That just makes me think that it all either caught God by surprise or He just didn't care enough to do anything about it. And as jaded as her diabetes can make me sometimes, I'm not willing to abide by either of those theories.

So I usually just keep quiet about it. I focus on making sure her sugar is the best it can be. Make sure she eats the right things and exercises and gets the proper dose of insulin. I tell myself that the Why doesn't matter because that's something I can't control, that it's the What I'm supposed to worry myself with because I can somewhat control that.

Still, that Why has a way of sneaking up. It preys on my mind. I'm sure you understand. We all have our own Whys.

It was preying on my mind last night at three o'clock in the morning. The Witching Hour, some call it. That time of night when the darkness is the darkest and supposedly the veil between the worlds of the seen and unseen thin enough that they intermingle. Her sugar had bottomed out. I was trying to keep her awake enough to drink some juice and not doing a very good job. She kept nodding off, and I'd have to shake her. That's when the Why came again.

"I'm sorry you have to do this," I whispered to her.

She nodded—she always nods at three in the morning, that's all she can do—and felt for the straw in her cup.

"I wish I could make it go away."

Nod and slurp, and I figured that if she wasn't asleep yet she would be soon, which meant I'd have to shake her awake again so she could finish. And then I'll have to wake her again fifteen minutes later to make sure her sugar was going in the right direction.

"I know it's not fair."

But not a nod that time. That time, it was, "It's okay. We love each other through it."

She finished her juice and curled up under the blankets again. I sat there watching her, trying to figure out if what she said was just her sleep or herself. I figured that didn't matter.

I also figured that if there really was a reason, maybe that was it. Maybe that's why God allows so much suffering. Because through suffering we learn not just to love, but to love more.

And if this world needs anything, it is that.

(If you'd like to make a donation to JDRF, you can click on the link to your right and it will take you to their site.)

Share and Enjoy:

November 28, 2011

Future Billy

image courtesy of photobucket.com

It seemed an easy enough thing—fill up the gas tank on Friday afternoon so I wouldn't have to do it on Monday morning. And in all honesty that's exactly what I meant to do. But as I was nearing the gas station in town, my favorite song came on the radio. I was so busy singing it that I drove right past.

I could have turned around—the Food Lion was right up ahead—but I didn't do that, either. The song was still on, for one, and so I was still singing. And for another, I'd decided by then that none of it really mattered anyway. I had enough gas to get home and enough to get back out again, and I wouldn't be driving my truck all weekend. Besides, it was Friday afternoon. Weekend time. I'd fill up later.

Later came this morning. Monday morning. Monday morning at 6:30. Monday morning at 6:30 in near total darkness and pouring rain. And as I stood there wet and shivering watching the dollars and gallons tick away, I discovered two things. One was that the very last thing anyone should have to do on a Monday morning is stop and get gas. The other was that Past Me had screwed Present Me yet again.

The sad thing is it wasn't the first time that had happened. In fact, it happens quite a bit. Call it what I will—being an adult, not putting off for tomorrow what I could do today—it all sounds good in theory but tends to fall apart in practice. Because when it comes right down to it, I'm pretty much living for the now. That's not a bad thing, really; most of the advice we get on how to live says the present is all that matters. The past is gone, so there's nothing we can do about that. The future isn't here, so there's no use worrying about that. All we have then, and all we need, is this moment. This now.

So that's what I've tried to do most of my life—live for this now. Be in the present. And you know, it often doesn't work very well. I've also tried living in my past. That works even less.

This morning, in the middle of pumping gas and shivering and yawning, I realized what I'd been doing wrong all this time. Living in the present kind of sucks. Not right now, maybe. Not usually. But later. And most of the time.

Because none of us are really only one person, we're actually three—there's the person we were earlier, the person we are now, and the person who comes later. Where I screw up is that I tend to think more often about Present Me and not nearly often enough about Future Me. Which, to really confuse you, often makes Present Me really not like Past Me very much at all.

It's confusing, carrying three people inside you. And yet that's what we all do. No wonder we seem so tired and stressed all the time.

I'm big on the idea that the simpler we make our lives, the better off we'll be. If we don't have too much and don't do too much and don't want too much, chances are we'll be much happier. I really believe that.

That's why I'm going to think more of Future Billy. I'm going to try and do more now so he won't have to do so much later. And I'm going to be more willing to put up with a little discomfort so he'll be able to smile.

It's perhaps the sincerest purpose we can have in this life—to live today with the intent of making tomorrow better.

Share and Enjoy:

November 23, 2011

Giving thanks

image courtesy of photobucket.com

On December 4, 1619, thirty-eight English settlers arrived on the north bank of the James River, approximately twenty miles from the colony of Jamestown, Virginia. The group's charter required that the day of arrival be observed yearly as a "day of thanksgiving" to God. The group's charter stated, "We ordaine that the day of our ships arrival at the place assigned for plantacon in the land of Virginia shall be yearly and perpetually kept holy as a day of thanksgiving to Almighty God." Captain John Woodlief officiated that first service, two years before the Pilgrims at Plymouth got the same idea.

Three years later the local Indians had enough of the English and decided that the only way to get rid of them was to go to war. The result was about a third of the colonial population of Virginia was killed. Tough times settled in—hunger, war, death, cold winters and unbearable summers. The New World that once held the promise of a new life had not become a hell.

I'll be honest and say I didn't know much of that. I learned in school about the Indian wars and the hardships faced by the settlers, of Pocahontas and John Rolfe and all the rest. But not the thanksgiving part.

And not this part either—even during those dark days of war and hunger and death, the settlers still paused each year to give thanks.

To me, that's amazing. I know there have been more than a couple Thanksgivings in my own life when the mood of our country was so hurt and so soured that the last thing on our minds was to say thanks to God. I think of the Thanksgiving just after 9/11. I think of ones in just the past few years, when recession and job loss made a feeling of appreciation next to impossible. And maybe for you, this year is particularly tough.

Sometimes we don't want to thank God. Sometimes we'd rather yell or cuss or plead, but never to get down on our knees and count our blessings.

Thing is, that's exactly what we're supposed to do. Good times, bad times, in-between times, sunshine or rain, laughter or tears, hope or hopelessness.

"Rejoice always, pray without ceasing, give thanks in all circumstances; for this is the will of God in Christ Jesus for you."

That's what I'm thinking about this Thanksgiving—how it's so easy to say thank you when times are good and so difficult to say it when times are not. But today, give thanks. Give thanks even if you don't feel thankful.

But I know this: God has built an oasis of beauty in even the ugliest of times. He has placed a blessing into every harm and pain. He has planted the seeds of joy in every tear.

And that is why we are called to give thanks in all things even if we cannot give thanks for them.

Share and Enjoy:

November 21, 2011

Getting what we're owed

image courtesy of globalpost.com

"Hmph" is all he says, and barely that.

Just a bit of air expelled through two tautened lips. He could say more—wants to, I'm sure—but the presence of two grandchildren in the room prevents any further commentary. That's a shame. You've never fully appreciated the news until you've watched it alongside my father's commentary.

The pictures on the television are the sort that's been played and replayed for a while now—tents and marches and protest, people with microphones shouting down with this and up with that. It's all a little too much, especially with the grandkids sitting there (right now they're working on the Play-Doh, but I know they're watching the screen).

I ask him if I should turn the channel. He works the chaw of Beechnut in his cheek and shakes his head. "Wanna see who won the race," he says.

So I watch the screen and I watch him and I watch my kids and I know that I am in the middle. I'm the bridge between him and them. I'm the link to hold the chain. And I realize that it really wasn't that long ago—if you can call twenty years long—that I was sure my father had no idea what the world was all about.

I think your teenage years are proof that the more you think you know, the dumber you really are.

My kids—his grandkids—are watching now. They're showing a policeman pepper-spraying a young man with long hair. Dad watches, too. I'm wondering what they're all thinking and if what they're thinking is pretty much the same. I think so. I think when you get right down to it, crazy looks crazy no matter what age you are.

In the end (and as it should), Play-Doh wins out over the news. The kids don't care what's happening a thousand miles away in some city. Their world's here in the mountains, where things are quiet and life makes more sense. But Dad, he keeps watching and working that chaw, turning it around in his mouth, thinking.

He's been in a good mood lately. Not that he isn't usually, just more so now. After thirty-five years of work, he has only three days left. Appropriately enough, Thanksgiving Day will be his first day of retirement.

It hasn't been easy, those thirty-five years. The ones before it weren't easy, either. He took the job for the same reason that many husbands and fathers do—because it paid well and offered a better life for his family. Certainly it wasn't because he enjoyed it—who would enjoy driving a rig up and down the Southeast, being separated from family, living off greasy truck stop food?

But he did it anyway. Day in, day out, through blizzards and tornados and hurricanes and floods. As a child I would pray every night for his safety. I still do. And God's watched over him—Dad's driven over three million miles without an accident. Back in '98, he had a stroke just outside of Fredericksburg. The doctors couldn't understand how he managed to drive his rig into the terminal and back it up to the dock before falling out of the cab. I could. It was his job, simple as that.

His formal education ended at the eighth grade. He grew up in poverty and hustled pool, but the Army straightened him out. And when it came time to marry and start a family, he swore he would give his kids a better life than he had.

That's exactly what he did.

On the television, one of the protesters says he's there because he wants a free education. He's owed that, he says, though he doesn't really say why. Dad doesn't say what he thinks of that, and I'm thankful. If he did, I'd have to write it with a lot of ampersands and exclamation points.

Because Dad and his eight-grade education knows more about the world than the people on television and their college degrees. Because he knows that no one is owed anything, and the sooner you realize that the better off you'll be. Because you have to work and scrape and save and drive the truck.

He won't say that only those who have stood up to work should have the right to sit down and protest. The grandkids are in the room.

So I'll just say it for him. Because after thirty-five years, I think he's earned it.

Share and Enjoy:

November 16, 2011

Jump

image courtesy of photobucket.com

(Originally published 8/18/2010)

Lately I've taken my lunch at the park, enjoying a bit of the country in the middle of the city. I'll park my truck by the baseball field, climb a small hill to sit on a smaller bench, and stare across the street. Just to see if it'll happen, finally happen, today.

The facelifted but tired house is home to a family I've never met and a young man I've come to know only from a distance. Ten or so from the looks of him. All boy. Grass-stained Levi's, alternating Transformer and John Deere T-shirts, and a filthy baseball cap. Always the cap. Homeschooled too, I suppose, since he's home every day and I've yet to see a truancy officer.

For about a week I sat and watched him take scraps of plywood and two-by-fours from behind his father's shed, gather the pile in the middle of the driveway, and proceed to hammer and nail every boy's first serious attempt at engineering—a ramp. It started small, not much more than a pine speed bump. But either his ambitions or an innate love for hammering and nailing got the better of him, and that bump got bigger. Much bigger. So much so that the upper part of the curve on the finished product nearly came to the bill of his cap.

This was someone not merely content to give a gentle tug at gravity's suppressive bonds. No, he wanted to break them with impunity. To fly.

He hammered the last nail a week ago and then pulled a muddy bike out of the shed, backed it up a good twenty feet, and climbed on. And then climbed off. A practice run, I supposed. The next day he actually pedaled halfway to the ramp. Halfway and half-hearted. And like any act undertaken with half a heart, it was doomed to fail. He squeezed the handlebars just as the front tire went from pavement to plywood.

And that's how it's been since. Every day I come here for my lunch, and every day he inches closer to that ramp but never quite close enough. And right now he's there again, sitting on his bike and staring.

I know why.

From where I'm sitting I can look to my right at a tight circle of iron tracks. The train runs at the park during the warmer months and is quite the attraction, both for the kids and the parents who once were kids.

As a child I was terrified of the train, convinced the tunnel on the far side was in fact a door to the underworld that swung only one way. Boarding it would mean the end of me. I would race through the tunnel and be swallowed by it, lost in the darkness forever. When I turned eight, I knew it was time to put up or shut up. I rode the train. I jumped. And to my unbridled delight I found that not only did the tunnel have an entrance, it had an exit as well.

And I can look to my left and see the spot where as a teenager I parked one Saturday night and listened as my girlfriend serenaded me with Poison's "I Won't Forget You," promising to never-ever-ever if I just fell in love with her. I liked the sound of that, so I jumped. She forgot about me three months later.

Which is why I understand the boy's apprehension. It's tough to jump. Tough to gather the nerve. Because you never know what's going to happen after. You never know if you'll land or crash, laugh or cry. And so we all sit and stare and wonder whether the chance to fly is worth the risk to fall. The good things in life are like that. They cost much but are worth more.

I look out over the park and see him tug on the bill of his cap. He rubs his hands and adjusts the pedals, positioning them just so for the right amount of initial oomph. And just as I think he's about to squeeze the handlebars again, he doesn't. He pushes harder. His eyes open wide.

And he jumps.

Share and Enjoy:

November 14, 2011

Changing Ethan's world

image courtesy of photobucket.com

Last week I wrote a post about my daughter. About how she thinks she's going to change the world and how I think no one can really. All she can do—all any of us can do—is change little parts of it. I tried explaining all of that to her, but it didn't quite work out. When it comes to adults who think they know everything conveying something to children who know they don't, something always gets lost in translation.

Then came last Friday.

I'm not sure if things have really changed that much or if my memory is simply fuzzy, but elementary school doesn't seem to be the same now as it was when I was a kid. What's taught seems the same—I remember learning about multiplication and the Declaration of Independence, just like my kids are learning now. I think the difference is what was left out with me is often included with them.

Things like divorce, for instance. A lot more of that nowadays than when I was a kid. And things like drugs and sex and alcohol, things that I never even considered until high school. Kids have to grow up faster nowadays. Many times, I don't think that's a good thing.

Sometimes, it might be.

Added to the drugs/sex/alcohol thing is the understanding that life can be a fragile thing, there one moment and gone the next. It's the sort of thing you want to keep far from a child for as long as possible. Not so for the students at my children's school, who for the past year or so have watched one of their own face his own mortality.

His name is Ethan Blevins. Eight years old, precocious, fun-loving, football fan. A normal kid for all of his life until the sickness came, one that worsened and wouldn't leave. Doctor visits and tests and several diagnoses later, it was revealed that Ethan had Leukemia. In one fell swoop, his childhood—and very likely his life—was over.

He's been in and out of the hospital since, in for a few months now. The cancer has taken its toll. Not just on Ethan, but his family. He's waiting on a bone marrow transplant now. No one's sure if such an invasive, scary procedure will do any good.

That we live in a world where children die from disease is a tragedy, but it's a reality no one can change. We may all pray for a day when a cure for cancer is found, but it's likely that day will come too late for little Ethan.

You can't change that. It's horrible and it's wrong and it's tragic. It's also reality. And yet rather than Ethan lament what he cannot change, he has focused on what he can. That's when he came up with the idea for the postcards.

Sending Ethan Blevins a postcard won't cure him. It won't bring peace to the world or jobs to the economy. It won't stop climate change. It will, however, bring a measure of hope to a boy who may not see his next birthday. The postcard and stamp might cost you a dollar, but to him, it'll be priceless.

He's trying to get a thousand of them, from all over the country. Family, friends, strangers, doesn't matter. Ethan has received hundreds so far, and he's read every one. It makes him feel better to know that people have thought about him. I think deep down, that's what we all really want.

If you're so inclined, you can send your own postcard to:

Ethan Blevins

University of Virginia Medical Center

7 West Room 7182

1215 Lee Street

Charlottesville, VA 22908

Tell him to hang in there. Tell him you're praying. Just tell him hi. You won't change the world, but you'll change him.

And you just might find yourself changed, too.

Share and Enjoy: