Billy Coffey's Blog, page 3

May 25, 2017

A song and a prayer

image courtesy of photobucket.com

image courtesy of photobucket.comIt’s a little late for me to be getting out in the backyard.

A busy day, too much to do. My wife said not to bother but I’m here anyway. I have the hose and two bags of seed plus what’s in an old popcorn tin which came from a place I can’t remember. It doesn’t matter that it’s near dark and the birds are all but asleep. They’ll need to eat tomorrow.

As a child I spent most of the summers weeding my grandmother’s garden and watching her call the birds.

Her beckons were wordless but sung instead, each chorus unique, drawing to the telephone wire which ran parallel to her yard the robins and cardinals first, then the jays and the mockingbirds, the Bobwhites. She called the sparrows and purple martins last. The chirps and whistles from her wrinkled lips came to me as the language of angels. Perhaps it was. My grandmother loved this land and every creature upon it, but the birds presided over a loftier place in her heart. A bird’s wings carry it closer to God than any of us could ever reach. She once told me that when we are wearied and spent and our voices grow small, the birds will carry our prayers to God’s ear.

Though I’ve never quite developed my grandmother’s talent for song, I take great care of the birds in and around our wood.

They are fed and watered without prejudice. I welcome the crows and starlings as much as the mockingbirds and finches. They sing to me and help keep the bugs away. My yard is a happy place. A safe one as well, in spite of the neighbor’s cat.

My habit has always been to check the feeders and and our birdbath every few days and replenish as necessary. That has changed these last months. I’m out here most every day now to top off the thistle seed or sow a little extra food in the grass for the doves and cardinals. I will not let the suet disappear since the woodpeckers prefer it. The same holds for the jays and their sunflower seeds, or the mealworms I set out in a barren spot among the grass for the robins and bluebirds.

Even in the rain, I go. Even on those chilly May mornings when the sun is not yet over the mountains. Even now, when all that is left in the sky are the stars above me. It is no responsibility or needful thing. My birds would get along fine without me. They would have the creek to drink from and the forest across the road from which to seek their shelter and food. They do not depend upon me, though I have come to depend upon them.

My wife watches from the kitchen window. She smiles as I scrub the bath or add a few extra sunflower seeds to the small wooden church attached to an iron shepherd’s crook which serves as one of our feeders. Sometimes she’ll bring out a bowl of the previous night’s popcorn for me to spread, or the heels of a bread loaf. She’ll tap the glass and point at the sparrow near my feet, so accustomed now to my presence that it no longer deems me a threat.

I don’t believe I’ve ever told my wife what Grandma once said about the birds.

She knows the tale of the telephone wire and the way Grandma sang but not about the prayers. It seems a silly thing on the surface. The sort of story any grandparent would tell a child in order that the world be made a more magical place. Of course birds do not carry the wearied prayers of weakened souls to the Lord’s ear. They are creatures, no more. Their songs are merely speech. Their wings may take them skyward, yet they are still earthbound.

I know this.

But I know as well that the woman smiling at me through the window was told not long ago that she is battling a form of leukemia. In ways I’m sure you will understand, that means I am battling it as well. We go through this dark world hand in hand with those we love. Many times, that is the only way we can get from one end of it to the other. We trust and fight and smile and believe. We pray, even in our brokenness and fear. Especially then.

That is why I am out here tonight with my buckets of seed. Why I will be here tomorrow.

Because I must feed my birds well and hope they fly higher.

May 18, 2017

When things were right

My kids tell me they’d rather be growing up when I did.

My kids tell me they’d rather be growing up when I did.Trade 2017 for, say, 1978. Anything with a “19” as the first two numbers will do. I’m certain the bulk of their evidence for this conclusion can be handed to the stories I tell about how life was once lived in our little town, which isn’t little so much anymore. “Back in the day,” as some would put it. Or, as I’m apt to say, “When things were right.”

Like how during the summer you might go all day without seeing your parents and your parents were fine with that, because they knew you were safe and you’d be home either when you got hungry or when the streetlights came on.

Or how you’d just keep your hand raised above the steering wheel when you drove down Main Street because everybody knew everybody else. You either went to school with them or went to church with them or were kin to them through blood or marriage.

How there was Cohron’s Hardware right across from Reid’s mechanic shop, and if you were a kid and knew your manners you get a free piece of Bazooka! gum at the former and a free Co’Cola in a genuine glass bottle that was so cold it puckered your lips at the other.

How, back then, you rode your bike down to the 7-11 to play video games—Eight-ball Deluxe on the pinball and Defender and RBI Baseball—and then pool what money you had left for a Slurpee and a pack of Topps baseball cards.

How maybe in the afternoons there’d still be change enough in your pocket to buy a Dilly bar from the hippie who drove the ice cream truck around the neighborhood. You’d hurry up and eat before the sun could melt it away and then head over for pickup games at the sandlot which rivaled any Game 7 of any World Series, and after, once all the playing was done and the arguing finished, you’d have the best drink of water in your life out of Mr. Snyder’s garden hose.

Evenings were for supper and bowls of ice cream fresh from the machine your daddy spent and hour cranking on the porch. You spent the nights catching lightning bugs and lying in bed slicked with sweat because there was only that one fan in the hallway. You’d go to sleep listening to the lonely mockingbird singing through the open window from the maple in the backyard.

So, yeah. I get it when my kids say that’s the life they want. Who wouldn’t want a childhood like that?

Truth be known, I spend a lot of time thinking about how I’d like to grow up back then again, too. Not so much to right certain wrongs (I have none, other than the day when I was six that I crushed a frog with a cinderblock just to see what it’d look like), but just to go back. To feel that sense of freedom again, and safety, and to know the world as wide and beautiful instead of small and scary.

I’ve talked to others over the years who feel the same way. Some grew up with me in this tiny corner of the Virginia mountains. Many more did not. They were born elsewhere in towns and cities both, yet each carry a story not unlike my own as one would a flame in the darkness. Even many who suffered horrible childhoods look back over them with a sense of fondness. They tell me things like, “Those were some good years, weren’t they?” Even when they weren’t.

This is part of what it means to be human, I think. We spent the first years of our lives wanting nothing more than to get away from where we are, only to spend the rest of it trying to get back.

My kids will be the same way. Yours, too. They will grow and flourish and have kids of their own, and those kids will be regaled with tales of how much better the world was back in the day. When things were right.

It’s only been in these last few years that my own parents have begun telling me the truth about my golden childhood. How they often struggled to keep a roof over my head and food on my table and clothes on my back. How it seemed like the country was on the cusp of some great abyss. People at each other’s throats. War looming. Nuclear missiles. How it was hard to tell the truth from the lies. Sound familiar?

My parents don’t look back on that time with fondness at all. To them, it was their childhood world of the 50s that was back in the day. That was when everything was right.

I’m sure my grandparents would disagree if they were yet here.

There were no good old days. I think we all know that deep down.

But that doesn’t stop us from believing there were, from wanting so desperately to know that one lie a truth in its own right. Because that’s part of what it means to be human, too. Maybe the best part. That deep longing and need for a time when things are right.

There are some among us who believe that will never be the case. Things were never right and never will be. I’m not one of them. Sure, deep down I know that my childhood wasn’t always the bright summer day I remember it to be now. But on some distant tomorrow? Well.

I’ve heard that heaven will be made up of all those secret longings we carry through our lives. I hope that’s true. Because if it is, I can take comfort in the fact that I’ll be spending eternity on a quiet street in a quiet town in a quiet corner of Virginia. I’ll be listening to mockingbirds and playing a pickup game of baseball and drinking from a water hose.

That’s all I want. Nothing more.

May 10, 2017

God’s name

I was six when I learned God’s first name was Andy.

It fit in that special way you can’t put to words but only feel. On most days back then I would get home from school in time to make a peanut butter sandwich and watch a few reruns on the TV. My favorite was an old black and white about this sheriff and his deputy who lived in a town called Mayberry. That sheriff’s name was Andy just like God’s, and I thought it a fine thing because the Andy on TV was always so kind.

It was funny because I didn’t learn all of this at home. My mother and grandmother served as my spiritual guides growing up, as is common in the South. Most everything I learned about God came from them. But not God’s name. At the time, I could only conclude they never said because they never knew. To them, God was only that. God. Which must have made Him like Mister Howerton down the street or Mister Snyder next door, nice enough old men but never ones you’d feel comfortable spending some time with. Not a God fit to play some catch or gig some frogs or go exploring in the cornfields.

That was the sort of God I’d always wanted. Still do.

No, instead I learned God’s first name in the most unlikely of places—church. More specifically, the Mennonite place out on Route 608 where the tombstones were all old and haunted and where you went inside the sanctuary and didn’t say a word because that’s where God was, Him being so Big and Other and us being so Small and Plain. The church had no piano, no baptismal pool, no adornments of any kind except for the wooden cross hanging on the wall behind the pulpit. But you could always feel Something lingering along those plain white walls, and some part of you always felt that Thing was watching to see what you did.

We sang our hymns a capella. I mostly mouthed them and nothing more. But then one Sunday we sang a hymn I hadn’t heard before, and in those words was God’s first name—Andy. I still remember how that felt. The sudden realization, like two pieces of a puzzle you’ve never quite figured out suddenly fitting together with such perfection. Andy—yes. At that moment, God became someone I knew rather than feared. He’d always known my name and now I knew His, and that made us friends.

And it was all so plain. That’s what got me. All this time there was this profound bit of information just sitting there, right in the chorus of that song, and I could not for the life of me understand why no one else reacted the way I did. Everyone else merely kept on what they were doing, eyes down and voices straining and tired, wanting to just get on with things. It was as if they didn’t even know what they were singing. I remember nudging my mother and father, trying to make them see. They didn’t. If my memory is right, all Dad did was tell me to hold still for just one hour. I went away from church that Sunday thinking the only thing I could—I’d been given some secret meant for no one else.

For months I sprinkled my prayers with God’s real name. “Dear Andy” and “Thank you, Andy,” and “Hey Andy.” You wouldn’t believe the difference it made. There were times as a kid when I’d catch myself thinking all I did was talk to the ceiling. Now, it felt like there was actually somebody there. Someone listening just like the Andy on the TV, looking at your mouth and your eyes and nodding his head with a grin.

Of course, none of this was bound to last. At a certain point I learned to read a little better and pay attention a little more, at which point I stumbled upon the truth of that song.

Not: “Andy walks with me, Andy talks with me, Andy tells me I am His own.”

But: “And He walks with me, and He talks with me, and He tells me I am His own.”

He. God.

Not Andy.

It was a tough thing to figure out. Like a lot of things you discover as you grow up, knowing I’d been wrong didn’t make me feel nearly as stupid as it did sad. The God I learned about at church was someone so completely different, so utterly powerful and holy, that He scared me. But Andy? That was a God I knew loved me and a God I knew I loved.

You can take anything you want from this. I’m not going to try to get overly theological. I’ll only say that there have been many times over the years when the world goes gray and the burdens pile up and everything gets so tired and utterly lost that I feel much more as the boy I was rather than the man I am. Maybe that’s true for all of us. Could be our bodies and minds grow old but our souls never do, that deep down we’re all just scared little kids. But it’s in those times when I’ll go for a walk or stare up to a darkened ceiling, and I’ll say much the same at forty-four as I did at six.

I’ll say, “Dear Andy,” because that’s still God to me.

March 13, 2017

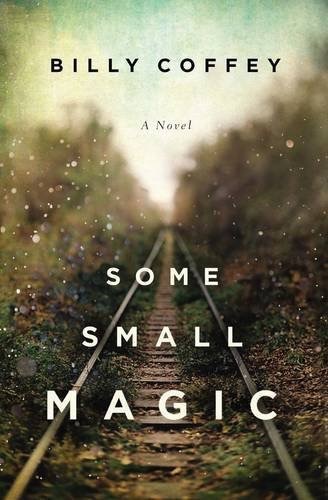

Release Day: Some Small Magic

Let me tell you about a kid I know, a boy named Abel.

Let me tell you about a kid I know, a boy named Abel.In many ways he’s not unlike a lot of children around here, meaning Abel’s family is poor and he has only one parent at home. That would be Lisa, Abel’s momma. Lisa spends most of her time waiting tables down at the diner. The tips aren’t much but they provide. There’s groceries enough, along with the rent money for their little rundown house along a dead-end dirt road outside town. Abel stays home most times. He came into the world with a mild form of brittle bone disease. Any awkward step can leave Abel casted and laid up for weeks. He’s got to be careful in what he does. Lisa worries about her boy. There are times, many times, when Abel knows himself a burden his momma cannot bear.

But I don’t want you thinking everything in Abel’s life is bad.

Far from it. He doesn’t have much but believes that okay; very often the ones truly cursed in life are those who have more than they know what to do with. It’s hard for Abel to get around with those soft bones, but there isn’t much exercise involved in reading. That’s what he does mostly, Abel reads, which has turned him into maybe the smartest kid I’ve ever known. And you can say all you want about the way his classmates pick on him, Abel’s got someone who will do just about anything in the world for him. Dumb Willie Farmer might only be the janitor at the elementary school (and might only be Dumb, as the name implies), but you will find no better friend. Ask Abel, he’ll tell you.

And about that house: sure it’s nothing more than a rented little shack, but it’s set along the edge of a field where the trains pass three times a day. Abel loves his trains. He’ll limp out there every day to count the cars and wave at the conductor. His daddy’s gone, prayed into the sky before Abel was born, but some days Abel will wave at that train going by and imagine a daddy he never knew waving back.

I’m not sure how life would have turned out for Abel had he not gotten into trouble with his momma and cleaned their house as an apology. Have you ever noticed how quick things can change off one small decision? It happened to Abel that way. He even cleans up the spare bedroom in back of the house where Lisa says he should never go, and that’s where he finds his daddy’s letters—shoved into an old popcorn tin and addressed to Abel Shifflett of Mattingly, Virginia. Some of these letters are dated from years back, but the one on top? Sent three weeks ago. Abel can only sit and ponder it all. His daddy’s not dead. And more than that, one of those letters reveal where his not-dead daddy is: a place called Fairhope, North Carolina.

It’s one of those times when all of life’s murky darkness gets shot through with a beam of light.

Abel knows what he’s supposed to do. He’s going to find his daddy and bring him home. Because that will fix everything, you see? His momma won’t have to work so hard anymore. The two of them won’t have to struggle. If Abel can get his daddy home, they’ll all be a family. It’s all Abel has ever wanted.

The problem is how a ten-year-old boy with soft bones is supposed to make it all the way down to someplace in Carolina without getting found. It’s too long of a way, and there will surely be danger. But then Abel realizes he has a secret weapon in his friend Dumb Willie, and the two of them hatch a scheme to run away from home. They’ll hop one of the trains coming by Abel’s house and ride it as far as they need. It isn’t a terrible idea so far as ideas go, but one which doesn’t take long to go awry. Hopping a moving train at night is an act fraught with peril, especially with a broken little boy and his not-so-smart friend. Abel’s journey seems to end before it begins when he is crushed under the rails.

But this isn’t a tragic story—oh no. This is a tale of magic big and small, and Abel and Dumb Willie aren’t the only ones at the train that night. Death itself has come in the form of a young woman to take Abel on. One look at this broken boy is enough to convince her this is a thing she cannot do. Even Death carries a burden too great, having witnessed so many children having their lives ended in so many needless ways. And while both Death and Dumb Willie (who is not so Dumb after all) understand what has happened to Abel, Abel himself does not. He convinces the strange but pretty girl who saved them to join in their journey, after which he promises to let her take them home.

So it is that Death itself accompanies two boys along the rails through the wilds of West Virginia and eastern Tennessee, clear to the Carolina mountains. Looking for a father long thought dead. Looking for a little magic.

That is the story in short for my eighth novel, Some Small Magic, which is out today.

There’s more to Abel’s journey (trust me, a lot more), but the rest is for you to discover. Believe me when I say you won’t be disappointed.

It’s my favorite book so far, and you can pick it up by heading here.

In the meantime, should you find yourself at a railroad stop in central Appalachia, do yourself a favor. Scan those boxcars as they fly past. They might not be all empty. And if you see three faces peering out at the blue sky, send a little prayer their way.

Because those three are bound west, toward home.

March 8, 2017

Still easily broken

image courtesy of google images

image courtesy of google imagesIt’s pretty rare that I ever get into anything truly personal here.

Family and the issues we face are usually dealt with in a funny or poignant way (at least that’s what I hope), which can sometimes give the impression that we in the mountains have this business of living down pat. I’m about to buck that trend.

The past month or so has been pretty hard on our family. I’ve had loved ones in the hospital for the flu and another whose body has all but given up. The word “cancer” has gone from being whispered about in private company to being acknowledged at the kitchen table. It’s been a trying time, a scary time—the sort of thing you start thinking only adults should have to handle and maybe you aren’t as much of an adult as you thought.

It’ll all be okay, of course.

The days will right themselves. It isn’t lost to me that everything I’m feeling is considered old news to a great swath of folks. Life’s only given is that we must all pass from it. Nothing of this world is made to be permanent, which is a lesson that comes early on in the Appalachian foothills. Things wear out, get tired and used up. Crops and seasons both rise up and bloom before being cut down. Our woods are filled with forgotten graves and the foundations of old homes left now to hold only memories and ghosts. Even these mountains, tall and solid as they are, wear away with the eons a millimeter at a time.

I know this. You know this. And yet they remain the hardest words to speak and hear:

each of us were born for leaving.

From an early age I was raised with the knowledge that each of us hold two parts—one temporary, the other eternal. Our shell of bone and muscle will decay at some point, freeing that holy spark within us to burn bright elsewhere. My mother’s parents drilled this into my head often, as the Amish usually do—all this world is for is getting us ready for the next. George MacDonald once said that “We should have taught more carefully than we have done, not that men are bodies and have souls, but that they are souls and have bodies.” My grandparents would have agreed.

But somewhere between the ages of nine and forty-four I seem to have forgotten that knowledge, or at least set it aside. Those thirty years or so had the opposite effect by convincing me life was a solid thing, wholly predictable, and if not permanent then at least long-lasting. There were reminders of otherwise along the way. My grandparents died. Several high school friends. I remember holding my daughter when she was born and my son a few years later and feeling a mix of awe and terror at how fragile and easily broken they were. Then all of that went away again, muddled by passing years which held nothing but the same old, the everyday.

Until this past month. These last weeks. Until the time came when the thin curtain over my life and my family’s lives was eased back a bit to reveal the truth on the other side. That’s why I decided to buck a trend with this post, because the truth I’ve seen is one we should all start holding a little closer to the heart—we don’t ever get stronger. Not really. We come into this world children, and I think that’s how we stay. We can pretend otherwise. We can lean on our intelligence and the strength of our bodies, we can seek shelter in the things we collect and the jobs we have and the dreams we count upon, but we’re still kids. Still fragile. Still easily broken.

Still sure to wear out.

I don’t know about you, but I’ve started paying a little more attention to that spark within us all. To the soul. It’s the one thing of us the ground cannot one day claim, the fire burning ever upward, pointing us on.

“There’s rest for the weary, a rest that endures.

Earth has no sorrows that heaven can’t cure.”

— David Crowder

March 1, 2017

The Bet

All of this happened a few weeks ago,

Valentine’s Day to be exact. It began like most things do when it comes to twelve-year-old boys, by which I mean a bet, offered so both may get over the one thing standing in their way, by which I mean fear. Speaking from experience, that’s how it works. Every fiber of your being propels you to do this one thing but deep down you know you’re too scared to do it, so you need a little help. A dare works well here. A bet works even better.

According to my son (who is both a champion darer and better), it was his friend’s idea.

I have reservations about that statement—I don’t know the friend, and this seems very much a thing my son would start—but I suppose it’s like every good story in that the beginning is important but the ending is everything. My son and his friend both happen to have crushes on two separate girls in their seventh-grade class. Alone, they could do nothing beyond staring goggle-eyed when both the girls and the teacher wasn’t looking. Call it a boy thing. When you’re twelve, any attempt to tell a girl that you like her will somehow get twisted into yanking on her hair or calling her a stupid head.

But then came an idea (again, from the friend): “I bet you won’t get her a box of chocolates for Valentine’s Day.”

“Bet YOU won’t.”

“I will if you ain’t chicken.”

Challenge accepted. My boy is a Coffey. Coffeys don’t back down.

My son relayed all of this to me on the evening of February 13 as we meandered the aisles of the local Kroger. He had money enough in his pocket for a nice box of chocolates. I was impressed and made that known, but also wary and played that close to my chest.

“Who’s this girl?”

“Just some girl.”

“What’s she like?”

“She pretty and goes to church and hunts and fishes.”

Good enough for me. You always want the best for your kids.

So we got the box of chocolates which he paid for with his own money and even stood there an answered every question the cashier asked (“You in love, honey?” “What’sat lucky girl’s name?”) and then we rode home and nothing else was said for nearly three days regarding the matter. I wanted to bring the girl and the chocolates up but never did. Sometimes it’s like fishing, raising kids. You got to let them come to you.

But then around that Friday evening the two of us were sitting on the porch. My boy leaned back in the rocking chair and let out a little kind of sigh, and I knew it was time.

“Whatever happened with your bet?” I asked him.

“It went okay.”

“She like those chocolates.”

“I’m not sure.”

“Why ain’t you sure?”

“Well, I went up to give them to her and then got scared, so all I pretty much did was toss the box her way and take off running. But I think she liked it. We’re texting now. She can’t date nobody, though.”

“Neither can you.”

“That’s what I tole her.”

“And what about your friend? He keep up his end of the deal?”

“No,” he said. “He turned chicken and said we never shook on it, which we did, and then he ate the whole box hisself.”

Then he grinned and I grinned and we rocked a while together. I said I was proud of him and it’s the truth. It can be a hard thing to talk to a girl, them being so mysterious in all their ways. Harder still to open up your heart and let somebody else get a peek inside. It was a risk, no doubt about it. But life is full of those. My son will find that out the older he gets, and he’ll come to learn there are really only two kinds of people in this world. There are the ones who dream and dare make those dreams true, make them real, and whether they find success or failure on the other side doesn’t matter because at least then they’ll know.

And there are the ones who dream but never dare at all and so settle.

I never want him to settle.

February 16, 2017

Cosmic scum like us

image courtesy of google images

image courtesy of google imagesOf the many times I mourn those who live in some city or another, night is when I feel sorry for them most.

I do not speak of crime, or more the threat of it—how so many in those cramped-close jungles of concrete and steel must lock themselves away along with the sun lest they be set upon by evil-doers. I remember taking a trip to Baltimore years ago to visit some of my wife’s kin. The windows of their house looked out upon busy streets filled with litter and exhaust. There wasn’t much to be seen, which was fortunate given I couldn’t see much anyway for the steel bars set over the glass to keep out intruders. I remember wondering how it was that anyone would live in such a way. A comfortable cell is still a cell.

I rather mourn city folk at night for the simple reason they are not afforded the luxury of a view on par with my own. Step out into my yard on any evening when the moon is small and the clouds scattered to the other side of the mountain, you’ll see what I mean. The stars in the Virginia sky are a wonder this time of year, so clear and close you are afraid your breath will chase them away like bugs. Millions of them scattered to all directions, never-ending and straight on to the very curve of the earth, divided overhead by a great milky arm of our galaxy itself. So many stars you cannot fathom to begin counting them all.

I like it out there, looking at them all. Few things in life offer such a perspective.

We humans have been staring at the stars for quite some time and for just that sort of thing—to gain a better view of ourselves and our place. Back when the smartest people around believed Earth occupied the center of the universe, it was fairly easy to see humanity as something special, set apart. Something fashioned by the very hand of God.

Of course the whole center-of-the-universe thing didn’t pan out. Turns out we’re not so special at all, cosmically speaking. The universe is vast and growing more so every second, and just about every part of it we can see is mostly the same. Ours is merely one planet among billions at the far edge of one galaxy among trillions, which over the centuries has changed the way we see ourselves.

Special? Hardly. Needed? Don’t even go there.

Humanity is about as inconsequential as a thing can be. We’re all no more than a happy accident. As the astronomer Carl Sagan laid our situation out, “We find that we live on an insignificant planet of a humdrum star.” Stephen Hawking made it sound even more pessimistic: “The human race is just a chemical scum on a moderate-sized planet.”

Yay us, right?

Call me crazy, but I am of the opinion this sort of thinking has seeped down to infect us all. Doesn’t seem to matter where I go or what I read or who I listen to, it’s all some version of that—nothing really matters because nobody really matters, so screw it because we’re all gonna die and be forgotten anyway. If the politicians or the media or celebrity culture doesn’t ruin us, we’re sure to ruin ourselves.

We’re not all that special.

Then again, maybe we are.

For all the talk about how our planet is so mundane, scientists are discovering the universe itself seems fine-tuned for life. Which is strange, given it seems for now that we’re the only kids on the block. So far the planets discovered beyond our solar system aren’t much Earth-like at all, much less places fit to support the sort of life we know. Intelligence seems a difficult thing to produce in the great beyond of space and time. It takes a lot more than water and oxygen and a few billion years of a stable environment to make even cosmic scum like us.

If that leaves you feeling a little lonely, you’re not alone.

Being special has its drawbacks. Given the size of the universe and the trillions of galaxies holding billions of stars, chances must be pretty good there is at least something out there, or someone. All that wasted space would be a shame otherwise.

But maybe even that doesn’t matter. The universe may be immense and growing, but the speed of light is still fixed. Life could be flourishing in the farthest corners of the cosmos, we’ll never know because we’ll never get there. Even over the span of thousands of years, we’ll be fortunate to visit even the closest stars. Maybe we’ll find someone to talk to. Maybe we’ll have only ourselves.

It seems arrogant on the face of it, believing everything I see in my small patch of Virginia sky exists for us alone.

I’ll be honest and say I have my doubts on that. But I also believe we’re much more than the insignificant inhabitants of an insignificant planet turning around an insignificant star.

We may not be so special in the grand scheme of things, but in our own tiny part of that grand scheme we certainly are.

We are each needed. Special. Wholly unique and so infused with a value far beyond our reckoning.

And maybe for the sake of us all, we should start treating each other like it.

February 9, 2017

A little sparkle in the muck

That pile of rock and dirt still sits in the back corner of our yard,

That pile of rock and dirt still sits in the back corner of our yard,and it still may be some gold in there, but there’s no telling because the kids haven’t dug through it in about forever. The last time they did (I can’t remember when it was, only that they were both a whole lot shorter), my son came running into the house with what looked like a piece of gravel.

Swore it was gold.

I told him the same thing I’d told him a thousand times before:

“Could be.”

How it all started was they’d seen a TV show about prospectors out West. One of them had struck it rich. The kids, young enough to believe if that sort of thing could happen to some guy in California then it surely could happen to them all the way in Virginia, decided they would have a go at it. They used the yellow plastic sifters we’d gotten at the beach that summer and went on out to the creek beside the house. It lasted about half an hour. Wasn’t so much the sifting they minded, it was the snakes.

But that pile of dirt and rocks at the end of our yard was well away from any lingering serpents, plus there was the fact it sat near enough to the neighbor’s oak to give them shade from the sun. There my two kids parked themselves for most of a whole summer. They separated dirt from rock and rock from what they called “maybes,” pebbles which gave off something of a shine and so would be studied later. Took them a few weeks, but that whole pile ended up being moved a good three feet.

Sometimes I’d sit on the back porch and watch them. There was an order to the kids’ work, a methodical examining which carried a strong current of patience beneath. Neither of them minded getting dirty or sweaty in the process.

“You gotta get down in all that muck,” my son told me one day, “because that’s the only way you’ll find the gold.”

To my knowledge that vein of leftover driveway gravel and leaves scattered by the wind didn’t pan out. My kids never did find their gold. Something other came along to capture their attention. Dragons, I believe it was. My daughter had read a book about dragons, which are vastly superior to gold, and so her and her brother spent the next few months out in the woods rather than in our rock pile, looking for dens and nests and serpent eggs.

I thought about their search for treasure this evening when I had the dog out and her sniffer led us both to the end of the yard in a meandering sort of way. Thought maybe I’d go inside and ask the kids if they remember the summer they spent sitting out there panning and sifting. I guessed they maybe would. If not, I would remind them.

Because there’s a lesson in that old pile, I think. One both of my kids would do well to remember.

They’re both getting toward that age when the world can lose a bit of its color. Things don’t seem so wondrous anymore. There are obligations and responsibilities. Things that have to get done. Adulthood is looming, for both of them. There will come a time when they’ll find much of the world is one sort of muck or another. Living can be a messy business. No one can get from one end of it to the other without getting a little dirty in the process.

But what I want them to know is there’s still treasure in there, treasure everywhere, so long as they’re both willing to put a little work into finding it. Won’t always be easy. Sometimes you’ll grab whole handfuls of days and months and even years and find little in there that sparkles. But you’ll always find something, that’s what I’m going to tell them. You’ll always find enough to keep you going.

And really, that’s all we need in the winter seasons of our lives. A little gold to keep us putting one foot in front of the other, to keep us warm and waiting for sun.

January 25, 2017

The symphony of us

image courtesy of google images

image courtesy of google imagesI’m not sure how I’ve come to share my house with a group of musicians, but such has been the case for the last few years.

Between both kids and my wife, no less than seven instruments can be heard playing within our walls on a nightly basis. For hours, I’ll add. Which is nice, don’t get me wrong, if there’s anything the world needs more of it’s music, but when you have a piano and flute and guitar playing three different songs in your ear at the same time, it can get hard to read your book. Or think. Or keep from going crazy.

The dog and I spend a lot of time outside in the evenings. It’s quieter out there.

Not that they’re bad, mind you. My family is gifted in ways I never was with the songs they play and the manner by which they play them. The kids especially. Though in all honesty, I’ve had my doubts.

Take the past week. Both kids have been hard at work practicing for a special district symphony performance—think an All-star game for band nerds. One plays flute, the other sax. Nights now they’ve sat in their respective bedrooms wailing away, and to be honest—to be very, very honest in a very loving way—I must admit this:

It sounds awful.

Seriously.

Now, sure, I have zero musical training beyond a fifth-grad stint with a plastic recorder. The only thing I can play well is the radio. But still. It’s bad. Off, somehow. They’re hitting the notes they’re supposed to, but there’s not doubt something is missing. Something vital.

Aside from you, the only living thing I’ve shared this with is our dog Lucy. She agreed and wanted to go outside.

But here’s the thing—my kids might sound awful and off, but they’re not.

I know this because I’ve been through the whole district thing before. Last year I sweated through the days leading up to their performance, thinking both of my kids would get up there with everyone else and hit one clunker of a note after another. Didn’t happen.

What did happen is they both played their notes to perfection in the same way they’d played them in their bedrooms, only now there were dozens of other instruments around them to fill in the gaps. My daughter played her flute, my son his sax, and where they left off other parts took over before my children swooped in again. The broken and jumbled sounds I’d heard them play at home weren’t broken and jumbled at all, those were merely the parts for them to play.

I’d forgotten they weren’t solo performers, they were part of a symphony.

I say all of this because it’s easy sometimes to take a look at my own life and see nothing but a jumbled and broken mess that sounds a little off. Maybe a glance at your own life would reveal the same. Days of the same old and nights spent so tired you can barely get one foot in front of another. Living for the weekend or the next day off. Watching the years tick by and wondering where they’ve all gone and what the point of it all is, and running beneath it all is a soft current of desperation because you just don’t know if it matters at all.

It’s easy for me to think that way when I catch myself believing I’m a solo. But what if I’m not? What if none of us are? What if we’re all playing our own parts in some greater orchestra instead, letting our instruments mingle with billions of others, leaping out and in such that we add to a melody so pure and beautiful the sound of it carries and carries on forever?

What if it’s not about us at all, and instead it’s about us all?

January 18, 2017

Our inner Bam Bam

He is eighty-one pounds of pure energy, a spring wound tight and apt to blow at any point into any direction,

and he has lived across the street from me for the entirety of his nine years on this planet. His name isn’t near as important as the nickname he’s been given.

We call him Bam-Bam.

Pure boy, Bam-Bam. Blond haired and thick-chested, he has the eyes of one both enthralled with the world and eager to conquer it. I’m not sure how far he’ll get in that regard, but he’s done a fair job subjugating the neighborhood. Every house on our block is his domain, every bit of dirt his playpen. You’ll see him zipping down the street on his bike (complete with one of those electronic gizmos on the right handlebar he turns to make a motorcycle sound), or his scooter, or his Big Wheel. Very often he’ll be half-dressed. Bam-Bam doesn’t hold to shirts or shoes, preferring the feel of the wind at his stomach and the good earth between his toes.

His momma tries to dress him, I promise you. It doesn’t take. The other day I watched Bam-Bam come out the front door decked out in so many layers you would have thought he was embarking on an arctic expedition. Two minutes later I looked again, and all he had on was his jeans. I never knew what he did with those clothes until the mail lady came the next day and dug out a sweater, a scarf, and a heavy coat from the mailbox before putting in the mail. From what I heard, Bam-Bam had to answer for that one.

He is impervious. Cold doesn’t bother him, or snow.

Bam-Bam has a penchant for running around in the yard during thunderstorms and soaks up the heat like a lizard. Think of a mini-Jason Bourne.

Not that everyone on our street is always thrilled when he’s around. I can’t count how many times I’ve had to tell Bam-Bam not to shoot at our birds (not that he listens, and not that the birds are in any danger; Bam-Bam loves to hunt, but you can’t kill much with a Nerf gun) and to please-for-the-love-of-God don’t run out in the road when Harold Thompson races by in his souped-up Camaro. He’s loud: the only thing more ear piercing than Bam-Bam’s laugh (which is near constant) is his crying (which is just as often). And you have to be careful what you let him do. Bam-Bam is more than willing to help you with just about everything, so long as you realize what you’re trying to fix will likely end up more broken if he’s involved.

You have to love him, because he’s that way. But that won’t stop you from taking a peek out the window to make sure he’s not around before you step outside to do something. Bam-Bam’s daddy summed it up nicely last summer when he told me, “My boy’s a blessin’, no doubt. And he also must be punishment for some past sin I cannot reckon. Either way, I expect that boy’s gone drive me to drink.”

I could only agree.

And yet I will sit on our porch in the evenings after school and watch him try to shoot down a cloud or sneak up on a deer or spin himself in circles until he either yarks up his lunch or falls down giggling, and I can feel nothing but envy for my neighbor Bam-Bam.

Because I was once like him, once upon’a. I was that boy through and through, and so was my son (truth be told, my son still sometimes is). There was a time I treated life a gift to unwrap every day, and I looked upon it all with an unquenchable joy.

There are times I wonder where that boy I was went.

Maybe he’s gone, died away so the man I was bound to be could come. And maybe he’s still inside me somewhere, wanting out.

It’s funny how so much of our youth is spent wanting to be grown up, only to spend so much of our grown-up years wanting to be kids again.

I’ve heard that youth is wasted on the young. I think wonder is, too.