Foster Dickson's Blog, page 72

November 22, 2016

A long, long pattern of disrespect

Although I supported Hillary Clinton in the 2016 presidential race, her defeat didn’t surprise me. The amount of time and energy that has been put into discrediting Hillary Clinton has been astounding, and it certainly didn’t start with “Crooked Hillary” or “nasty woman.”

I’ve never understood the right-wing obsession with absolutely destroying the Clintons. I can remember back in the 1990s when conservative pundits began calling our First Lady by her first name, Hillary, a moniker obviously intended to degrade her and to imply that she wasn’t worthy of an honorific. For more than two decades, Hillary Clinton did manage a successful political career despite that long, long pattern of disrespect, but ultimately she couldn’t overcome it, even though current vote tallies say she beat Donald Trump by 1.5 million votes. This pervading idea that Hillary Clinton is not worthy of our trust, our respect, or our votes began in the 1990s and led millions of Americans in 2016 to rationalize a vote for Trump by saying, “I just can’t vote for her.”

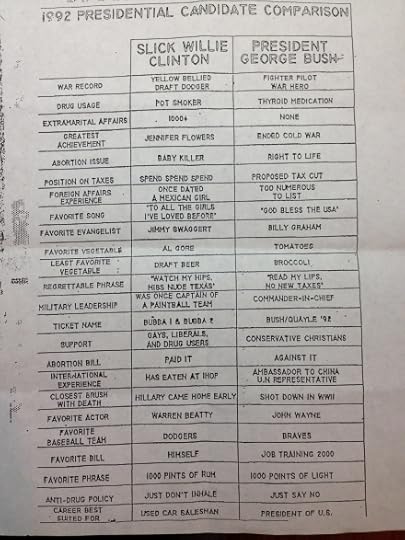

Recently, I was cleaning out some boxes of old mementoes and found this. Back before smart phones, before Facebook, even before email, people used to circulate these kinds of political rhetoric via fax machines. My very conservative father worked for the phone company and would bring these things home, and knowing that I favored Bill Clinton in 1992, he made sure to give me this one. The little dot-matrix fax information at the edge of the page dates it in September 1992, a month after I became old enough to vote, and two months before William Jefferson Clinton, AKA Slick Willie Clinton, would become president. If you take a moment to read these comparisons, the intent is obvious: to make then-candidate Bill Clinton so completely repugnant that no one would dream of supporting him. This onslaught of political mud is where Hillary Clinton’s controversial loss in 2016 began.

Filed under: Critical Thinking, Voting

November 20, 2016

A writer-editor-teacher’s quote of the week #146

The daily newspaper is one of any city’s most important institutions without which its existence would be completely different. The newspaper which has the respect and trust of the community is in a strategic position to exercise considerable power. It is a stabilizing influence, a matter of civic pride and a force for progress. A newspaper which lacks the confidence of its constituents is not only at personal disadvantage as a commercial enterprise but is a social misfortune. All citizens have a profound personal interest in the development and maintenance of a strong competent local journalistic medium, They need it as much as they need good government, first-class schools, recreational and cultural activities and other factors which make for good community living today.

– from the chapter “Servicing Readers” in Principles of Editorial Writing by Curtis D. MacDougall, published in 1973

Filed under: Teaching, Writing and Editing

November 18, 2016

This Sunday: J. Mills Thornton and Randall Williams

I got this message in my email and thought more folks would be interested:

Please join us at the NewSouth Bookstore on Sunday, November 20 at 2pm for a special event. Historian J. Mills Thornton III will speak about and sign copies of his newest book, Archipelagoes of My South: Episodes in the Shaping of a Region, 1830-1965. Author Jane Dailey calls this new work “a marvelous collection of essays on the South. Based on exhaustive research and ranging across two centuries,” Dailey adds, “Thornton’s prose is always lively, his analysis razor-sharp.”

Author and NewSouth Books Co-founder and Editor Horace Randall Williams will also present and sign copies of his recently released 100 Things You Need to Know About Alabama, a work sponsored by the Bicentennial Commission in anticipation of the 200th anniversary of statehood Alabama will celebrate in 2019. In short vignettes, 100 Things looks back at the events, places, and peoples that have shaped the Heart of Dixie from the time of the earliest Native American settlement. The book offers a concise but authoritative portrait of our state.

Hope you can be with us at 2pm this coming Sunday at the NewSouth Bookstore, located at 105 S. Court Street in downtown Montgomery, at the corner of S. Court and Washington. Light refreshments will be served.

For more information or to reserve a signed copy of these books, call 334-834-3556.

NewSouth Books, 105 South Court Street, Montgomery, AL 36104

Filed under: Alabama, Black Belt, Civil Rights, Literature, Race, Reading, Social Justice, The Deep South, The South

November 13, 2016

A writer-editor-teacher’s quote of the week #145

Man proposes and disposes. He and he alone can determine whether he is completely master of himself, that is, whether he maintains the body of his desires, daily more formidable, in a state of anarchy. Poetry teaches him to. It bears within itself the perfect compensation for the miseries we endure. It can also be an organizer, if ever, as the result of a less intimate disappointment, we contemplate taking it seriously. The time is coming when it decrees the end of money and by itself will break the bread of heaven for the earth! There will still be gatherings on the public square, and movements you never dared hope participate in. Farewell to absurd choices, the dreams of dark abyss, rivalries, the prolonged patience, the flight of seasons, the artificial order of ideas, the ramp of danger, time for everything! May you only take the trouble to practice poetry. Is it not incumbent upon us, who are already living off it, to try and impose what we hold to be our case for further inquiry?

– from the “Manifesto of Surrealism (1924)” in Manifestoes of Surrealism by André Breton, translated by Richard Seaver and Helen R. Lane.

Filed under: Literature, Poetry, Teaching, Writing and Editing

November 6, 2016

A writer-editor-teacher’s quote of the week #144

A little something to think about before Tuesday’s election:

To Tom Hayden, participatory democracy meant “number one, action; we believed in action. We had behind us the so-called decade of apathy. We were emerging from apathy. What’s the opposite of apathy? Active participation. Citizenship. Making history. [ . . . ] Voting was not enough. Having a democracy in which you have an apathetic citizenship, spoon-fed information by a monolithic media, periodically voting, was very weak, a declining form of democracy. And we believed, as an end in itself, to make the human being whole by becoming an actor in history instead of just a passive object. Not only as an end in itself, but as a means to change, the idea of a participatory democracy was our central focus.”

– from the chapter “Participatory Democracy” in Democracy is in the Streets: From Port Huron to the Siege of Chicago by James Miller

(*The late Tom Hayden was a founder of Students for a Democratic Society in the 1960s. He passed away earlier this year.)

Filed under: Civil Rights, Critical Thinking, Social Justice, Teaching, Voting, Writing and Editing

November 3, 2016

Fiddling While Rome Burns

Even though they’re not in session, members of Alabama’s legislature are busy these days. Some are trying to impeach Governor Bentley because they believe that he was having an extramarital affair on the company dime, and others are trying to pick up the pieces after the short-term “fix” for our Medicaid system. Still others, like Cam Ward, are busy staring down a federal investigation of our prisons, since the construction bill didn’t pass. And former speaker Mike Hubbard is busy appealing his conviction to avoid spending time in those prisons.

Yet they aren’t the only busy folks in state government. Robert Bentley is very busy: defending himself against the impeachment committee and against attacks from state auditor Jim Zeigler, and setting up a commission to study gaming in the state. Education bigwig Craig Pouncey is busy combating accusations made against him in an anonymous letter circulated during the search for a new state superintendent, which he believes may have cost him the job. Former ALEA secretary Spencer Collier has been busy working to clear his name after the governor fired him. AG Luther Strange is busy going after Victoryland. The state’s top Democrats are busy arguing over who ought to be in charge of their party. Chief Justice Roy Moore should have been busy cleaning out his office, since a panel of judges suspended him without pay, but as with most of his public positions on issues of consequence— he refused!

They’re all very busy—fighting with each other. Bickering, wasting time and money and energy, paying lawyers, each declaring himself to be the righteous one in a den of thieves. And the state’s problems are no closer to being solved.

These major news stories in our state have one thing in common: none of them have anything to do with moving Alabama forward. Solution after solution is proposed – an ethics bill, an immigration law, a lottery, a bond issue for prison construction – and one by one, they either fall on their faces or don’t accomplish much. Some are dismantled by the courts for being unconstitutional; others never make it out of the State House. Our so-called leaders are fiddling while Rome burns.

Running for elected office is a choice. Making that decision, to put one’s name on the ballot, implies that the candidate is ready to participate (or even lead) in solving the problems of public administration, no matter how great or how small. Anyone running for the office of governor, senator, or representative in the state of Alabama must be well aware of the manifest problems facing our state: high poverty rates, a lagging education system, crumbling infrastructure, overcrowded prisons, a weak tax base, a faltering Medicaid system, high unemployment, and a whole plethora of social ills. If a person does not have a viable idea for solving at least one of those problems, he or she should not even run for office.

To anyone thinking of running for public office in Alabama: if you can’t create a plan, lead the effort, and coalesce the votes to solve at least one of our problems, the people of Alabama don’t need you. Stay home. Don’t come to Montgomery. Run your business or do your job, spend time with your family, watch some football, go deer hunting or bass fishing, coach little league, find a hobby. Just don’t run for office.

When we go vote next week, the people of Alabama need to help ourselves by refusing to support do-nothing politicians who gum up the works. The state legislature has a transparent online system that allows anyone to learn about and track bills in both the House and Senate. Alabamians need to stop complaining and use it to educate ourselves, and then we can ask real questions about the votes, the bills, and the everyday results for our people. When measures are proposed to solve a major state problem, we need to ask our local representatives and senators how they voted and why. Until we do that, we’re no better than the politicians that we criticize so freely.

Filed under: Alabama, Critical Thinking, Local Issues, The Deep South, Voting

November 1, 2016

“Uncle Henry is Wrong”

So you thought you knew all about arts education, all about how it’s frivolous and non-necessity, and all about how people with arts degrees can’t get jobs, can’t keep jobs, and end up as starving artists living in their parents’ basements . . . ? Well, you’re wrong.

Filed under: Arts, Critical Thinking, Education

October 30, 2016

A writer-editor-teacher’s quote of the week #143

Early on in your education you are socialized to understand the need to support the power structure, primarily corporations— the business class. The lesson you learn in the socialization through education is that if you don’t support the interest of the people who have wealth and power, you don’t survive very long. You are just weeded out of the system or marginalized.

– from the chapter “Beyond a Domesticating Education: A Dialogue” in Chomsky on MisEducation by Noam Chomsky, edited by Donald Macedo

Filed under: Critical Thinking, Education, Schools, Social Justice, Teaching, Writing and Editing

October 27, 2016

Reading “Off Magazine Street”

Because of the infamy of our go-to Southern novels, gems like Off Magazine Street often go unnoticed. At once vulgar and charming, grotesque and wonderful, Ronald Everett Capps’ story of two alcoholic writer-teachers who take in the crass teenage daughter of their dead, morbidly obese lover— it’s not for everybody.

Though we may gorge our young on readings and re-readings of To Kill A Mockingbird, Beloved, Confederacy of Dunces, and As I Lay Dying – all excellent novels – our neglect of a certain kind of cult-classic Southern novel relegates novels like this one, Train Whistle Guitar, and The Dog Star to the literary backwaters, only to be discovered by chance or by recommendation. You wouldn’t have run into Off Magazine Street on any high-school syllabus or summer reading list, because I don’t see any teacher being able to teach it.

In the novel, Capps uses the cuss words like most writers use commas, and the novel’s anti-hero Bobby Long is a shameless drunk, a sex fiend, and a manipulator, while his sidekick-collaborator Byron Burns isn’t much better. The two desperately misguided wanna-be romantics conveniently excuse their laziness and their perversions with the insistence that their lifestyle, which centers around Popov vodka, casual sex, and literary storytelling, is a conscious choice based on an examination of existential truths.

The novel opens by introducing us to four characters: Bobby Long, a middle-aged Marine Corps veteran whose fiercely infected big toe causes him to shuffle around in one shoe and one flip-flop; Byron Burns, a literary drunk slightly younger than Bobby; Lorraine, an extremely fat homeless woman with mental illness issues; and Hanna, Lorraine’s sixteen-year-old daughter who lives unhappily in Florida with her grease-monkey boyfriend. Soon, three of the four come together in New Orleans – Bobby, Byron, and Lorraine – and they move into a cheap hotel room, their home base above Tiny’s bar. The hotel room, which only has one double bed, is nothing more than a place to pass out, play cards, and have sex.

The three oddballs don’t seem to accomplish much for most of the dialogue-heavy opening chapters. But we get a sense of who they are. This portion isn’t really the story, just the prelude. We have to understand these two men, and their relationship with Lorraine, to understand what will come next.

Soon, Lorraine experiences a bout of unbearable pain but is refused treatment at the hospital, because of their inability to pay the bill. Bobby and Byron carry her home in the trunk of their beat-up car, since she is too big to fit in the car. The trio continues their debauchery for another short while . . . until Lorraine suddenly dies.

Her death, which the two men take as casually as anything else they do, brings Hanna to New Orleans from Florida. The teenage girl, who is quite attractive, has come to collect her mother’s belongings, which hopefully contain some money. Bobby and Byron assure Hanna that there is no money for her to collect, which is a problem, since she doesn’t have enough for a bus ticket home. Here she is, a pretty girl stuck in a cheap hotel in a strange town with two middle-aged drunks whose three main activities have been: swilling drinks, playing gin rummy, and molesting her mother.

Hanna’s arrival marks a turning point for the two men, who urge her to stay with them, not to return to Florida, under the guise that Lorraine’s disability check will arrive in a few days. (Bobby promises to forge it for her, so she can cash it.) Of course, their real goal is to have her as a far more preferable replacement for Lorraine. But the streetwise young girl knows better than to fall for their charming banter and long-shot promises. Taking the hard-line, she will stay with them for a few days, until the first of the month, then she will claim her mother’s check and go.

But Hanna stays longer than that.

The remaining two thirds of Off Magazine Street turn Bobby and Byron from pure degenerates into somewhat admirable wastrels. Once the ruse of Lorraine’s check is revealed for what it is – a way to keep the girl around while they try to have sex with her – the second phase in their efforts involves a vague promise to educate the girl, who is a ninth-grade dropout. The shift in the story comes when Hanna lets down her guard for a moment and perceives the real benefits of allowing these strange drunks to share their one meaningful gift: an understanding of great literature.

The education of Hanna begins informally as Bobby and Byron “assign” her a variety of classic novels that they retrieve at a nearby public library, among them Carson McCullers’ The Heart is a Lonely Hunter. Once entirely skeptical of schoolwork and required readings, when Hanna gives the books a chance, she begins to see these two lazy, lying perverts as something more. The intimation of the education and of their understanding come to her as comments or mannerisms barely hidden within drunken rambles, and the novels, which she acquiesces to read, only reinforce that these two men are more than she once thought. Her reticence wanes as her comprehension grows.

As we watch the uptrend of Hanna, Byron and Bobby make the decision to leave their small hotel room and move into a house off Magazine Street, near the river. They make a mild, half-hearted effort at fixing up the dilapidated, unfurnished wreck, and quickly build a new life that includes an assortment of derelicts and drunkards who live in a nearby vacant lot they affectionately call the “outdoor living room.”

As this point in the story, though Bobby’s childish ways continue on their normal trajectory, we see something grow in Byron: a vaguely paternal spirit, a semblance of responsibility toward Hanna. However, the two men don’t change much— though their foolish efforts have noble results. One day, Bobby disappears, and when he returns, they find out that he has gone to bring to fruition a cockamamie scheme to coerce man they know, a high school principal in Georgia, to manufacture a transcript for Hanna that will allow her to enter the twelfth grade. As Bobby holds up the papers, official documents now proclaim that Hanna is no longer a dropout from Florida, but an honors student from Georgia.

As Hanna first enters then begins to traverse the unfamiliar world of high school, she encounters real-world opposition. Beside the homework and various projects, some of the other girls don’t like this attractive newcomer who has caught the boys’ attention. However, compared to her life so far, these obstacles are easy to surmount with her own brand of crass audacity. Hanna soon makes a new friend, and her life begins to be relatively normal— relatively.

Though they have worked hard and made their best efforts to convince Hanna of the merits of an education, Bobby and Byron realize what this means. When Hanna finishes high school, she will leave them. She has already made new friends and even attracted the interest of boy, who takes her to a dance. The kicker comes when Hanna starts asking about going to college.

As the novel’s story ends, we see this unlikely family do what all families do eventually: face the immutable truths of time. Young people grow up, and their elders have to let them go. After the complex work of raising and educating this teenager is complete, she will leave them and go out into the world to experience it for herself, after having learned both what to do . . . and what not to do. Hanna arrived as an angry, suspicious girl, but she leaves as a young woman who knows that life can be more than what she first thought.

Although vulgarity and even obscenity pervade Capps’ novel, it isn’t without a purpose. Though Bobby’s and Byron’s passé attitude toward their own laziness and alcoholism and the crass lewdness of their constant attempts to procure sexual favors can’t be ignored, Bobby and Byron are also sympathetic, even lovable characters. We learn as we read that, however intellectually brilliant he may be, Bobby is a child stuck in a man’s body, and Byron is an eccentric with a near-total disdain for ordinary social norms. While each man has his faults, they also have their own unorthodox brand of goodness. To Bobby and Byron, all people are equal, all are worthy of kindness and friendship, and with a complete lack of judgment, these ne’er-do-wells embrace the people who enter their lives with full gusto. And if they hadn’t been that kind of people, Hanna might have simply gone back to being the bored concubine of a redneck mechanic in Florida and never transcended her circumstances.

Though only loosely, Off Magazine Street became the basis for the 2004 film A Love Song for Bobby Long, which is how I found out about the novel. Much like the modern classic Forrest Gump, this film adaptation only takes a few key elements and builds a much cleaner story with tidier themes. For example, the film’s story begins after Lorraine is dead, so she is only discussed, and she is not described as morbidly obese. Also, where the novel makes one scant reference to three men who could be Hanna’s father – one of them was “really smart” – the film takes that father-daughter connection all the way to fruition.

Though both Off Magazine Street and A Love Song for Bobby Long are endearing stories about an unlikely family of derelicts who find solace in each other, their components, the reasons for the characters’ interpersonal connections, and their endings are fundamentally different. No matter the reasons for the excisions and alterations, I’m glad that the film led me to the novel.

Filed under: Alabama, Literature, Louisiana, Reading, The Deep South, Writing and Editing

October 25, 2016

Alabamiana: Pardoning Clarence Norris, October 1976

It was forty years ago today – on Monday, October 25, 1976 – when Clarence Norris was pardoned by Alabama’s governor, George C. Wallace. Originally from Warm Springs, Georgia, Norris was the last living one of the “Scottsboro Boys,” a group of nine black teenagers and young men who were falsely accused of raping two white women in 1931. He had skipped parole decades earlier, in the 1940s, and had been living as fugitive in New York. A newspaper story from the day after his pardon quoted Norris as saying, “a man should never give up hope. Even if it kills you, stand up for your rights.”

Though Norris’s history is difficult – a falsely accused, wrongfully convicted man who broke parole and hid in plain sight – Norris’s pardoner had his own difficult history, too. George Wallace had spent more than a decade, from the late 1950s through the early 1970s, as a symbol of vehement Southern opposition to racial equality. His 1963 Stand in the Schoolhouse Door and his opposition to the 1965 Selma-to-Montgomery March – both failed efforts – serve as excellent examples of Alabama’s recalcitrant mid-century attitudes toward racial justice. Though he did grant the pardon, Wallace still seems an unlikely agent for helping a 64-year-old black man who had forty-five years earlier been convicted of a crime he didn’t commit.

The Scottsboro Boys earned their dubious moniker in a series of events in northern Alabama in March 1931. Acting on charges made by two white women claiming they had been raped, the nine black men and teens were taken off their train in rural Jackson County, Alabama and tried in the county seat of Scottsboro. In three separate trials in early April, eight of the nine were convicted and sentenced to death. The remaining one of the accused was only 13 years old; he was convicted, though a single juror voted against the death penalty for him. Lawyers from the International Labor Defense and the NAACP got involved, and during that process, evidence surfaced that one of the women, Ruby Bates, admitted that she had not been raped. A year and a half later, in November 1932, the US Supreme Court ruled in Powell v. Alabama that the convictions would be overturned on the grounds that the young men did not have adequate legal counsel. Over the next five years, from 1933 until 1938, their cases bounced around the courts, and the men received a wide variety of unjust verdicts and sentences— especially unjust, considering that Ruby Bates came forth to testify in court that neither woman had been raped by the men who had been convicted of that crime.

The ugly injustice of what was done to the Scottsboro Boys further inflated Alabama’s reputation as a place where an obvious wrong would always stand if it meant showing even the smallest degree of racial toleration. The white accuser had recanted her charge, but the white-dominated “justice system” would never admit to treating any black man unfairly. This Depression-era precursor to the civil rights movement evidenced the harshness and brutality of the Jim Crow system in the South. By the mid-1940s, fifteen years after the incident that initially put him in jail, Clarence Norris took it on himself to be free of those circumstances.

Thirty years after Norris had left Alabama, NBC ran a made-for-TV movie called “Judge Horton and the Scottsboro Boys,” about the 1933 re-trial of another of the Scottsboro Boys, Haywood Patterson. It aired in April 1976.

At the time that the program aired, Nashville’s Tennesseean newspaper ran a substantial piece, mostly about Horton, by Athens, Alabama native Wayne Whitt. In the article, Whitt explains how the US Supreme Court had ordered a new trial, how the dignified Horton had been assigned the trial in 1933, and how he had stood up against the jury’s unjust guilty verdict. Judge Horton, he wrote, saw through the prevailing fear of ruling in favor of the black defendant, and that ruling cost him his judicial career.

Later that fall, Clarence Norris’s latter-day plea for a pardon meant that he could face the possibility of even more injustice. Although Alabama’s attorney general Bill Baxley was on Norris’s side, other Alabama leaders were not. An October 20 news story explained: “The Alabama pardon board has insisted he must return and be jailed without bond before a pardon will be considered.” Norris, who by then had been living in New York for twenty-three years, flatly refused. He had “spent five years on death row, then served 15 years of a commuted life term” already.

Writing in November 2013 for al.com, attorney Donald Watkins told his story of procuring the pardon for Clarence Norris. His editorial was prompted by the then-recent pardons of three others of the Scottsboro boys. Watkins explained:

Norris decided to pursue his pardon in 1972. He was living as a fugitive under an alias in New York. In 1974, the NAACP asked me to represented Norris in his quest for a pardon. This was one of my first cases as a lawyer. I had studied the Scottsboro Boys’ landmark cases in law school, but I never thought one of the Scottsboro Boys was still alive.

My early attempts to get a pardon for Norris were met with massive resistance from the Pardons and Paroles Board chairman, and the case quickly reached an impasse. I then reached out to my friend Milton Davis, who was a young lawyer in Attorney General Bill Baxley’s office, and asked for his help. Davis arranged a meeting with Baxley and me, and he also convinced Baxley to assign him to the case for the AG’s office.

He goes on to describe the work it took to bring around the man who would ultimately have to sign off: Pardon and Parole Board Chairman Norman Ussery, a Wallace appointee who took a good deal of convincing.

The wire story about the pardon ran nationwide on Tuesday, October 26, 1976. In sharp contrast to the grainy photos of a solemn Clarence Norris that ran alongside the tense stories about the tenuous days leading up to it, that day’s coverage shows a bright and smiling man. He had felt this coming, he told reporters, and had taken the day off. His NAACP lawyers had to come find him at a bar to tell him. And about Gov. Wallace, attorney Nathaniel Jones is quoted as saying that, despite the struggles to get there, “this act of compassion [ . . . ] is nevertheless praiseworthy.”

The next year, Clarence Norris made news in Alabama again. During its spring 1977 session, state legislator Alvin Holmes sponsored a measure that would have “provided $10,000 reparation to Norris,” but the measure failed to pass. That fact prompted attorney Donald Watkins to take action again, preparing a lawsuit on his behalf.

Clarence Norris passed away in January 1989, though ten years earlier, he wrote and published an autobiography, titled Last of the Scottsboro Boys, which is still available in used edition through a variety of booksellers.

Sources:

Wayne Whitt, “Drama Tells Courage of Alabama Judge,” Tennessean, April 22, 1976.

“Will never return, says Scottsboro ‘boy’,” AP wire. October 20, 1976.

“‘Scottsboro boy’ wants a pardon,” AP wire, October 10, 1976.

“Pardoned man’s reaction: ‘Never give up hope’,” AP wire, October 26, 1976.

“‘Scottsboro boy’ may now receive state compensation,” AP Wire, March 31, 1977.

“Damage suit drawn up for ‘Scottsboro boy’,” AP wire, September 2, 1977.

Filed under: Alabama, Civil Rights, Race, Social Justice, The Deep South