Dan Pollock's Blog, page 4

May 6, 2013

WORLD’S MOST PROLIFIC NOVELIST

In a previous post (“Art as a Job,” Thursday, February 28, 2013), I did a quick survey of some of the world’s most prolific novelists. Shelf-fillers Georges Simenon and John Creasey came in for honorable mentions, along with Isaac Asimov and R. L. Stine.

In a previous post (“Art as a Job,” Thursday, February 28, 2013), I did a quick survey of some of the world’s most prolific novelists. Shelf-fillers Georges Simenon and John Creasey came in for honorable mentions, along with Isaac Asimov and R. L. Stine.Somehow I missed the Guinness-certified record holder for most published titles, a Brazilian pulpmeister known as Ryoki Inoue. In fact, according to a 1986 Wall Street Journal profile,“When the Guinness Book of World Records recently affirmed Mr. Inoue's No. 1 ranking in titles published, the award certificate was already 15 books out-of-date by the time it arrived from England.”

How fast can Inoue write (yes, he’s still at it)? Again to quote the Journal, “He has churned out complete chapters during trips to the bathroom; a whole book while having his truck worked on in a garage; a novel and its sequel in an afternoon on the beach.”

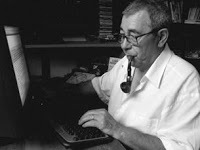

Ryoki InoueWhen the WSJ story was published in 1996, Inoue had published 1,039 books—under his own name and 39 pseudonyms. “Mr. Inoue writes books faster than 10 Brazilian pulp presses combined are able to publish them. ‘Brazil hasn't yet developed the capacity to absorb me,’ says the pipe-smoking 49-year-old author, whose father was Japanese and mother was Portuguese.”

Ryoki InoueWhen the WSJ story was published in 1996, Inoue had published 1,039 books—under his own name and 39 pseudonyms. “Mr. Inoue writes books faster than 10 Brazilian pulp presses combined are able to publish them. ‘Brazil hasn't yet developed the capacity to absorb me,’ says the pipe-smoking 49-year-old author, whose father was Japanese and mother was Portuguese.”The secret of Inoue’s prodigious output? Prodigious work. The same secret practiced on a daily basis by all phenomenally successful writers.

Inoue reckons the creative process as “98% sweat, 1% talent and 1% luck." He has been known to finish a 200-page story—bang-bang westerns are his favorites—at a single sitting. (I assume brief breaks, unless he’s catheterized.)

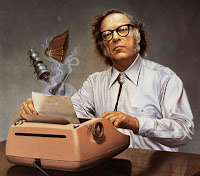

Isaac AsimovI mentioned in that earlier post that the late Isaac Asimov could write about as fast as he typed, which for him was 80 words a minute. Inoue may write even faster. According to one testimonial on his website, “Many people cannot read at the same speed that he writes.”

Isaac AsimovI mentioned in that earlier post that the late Isaac Asimov could write about as fast as he typed, which for him was 80 words a minute. Inoue may write even faster. According to one testimonial on his website, “Many people cannot read at the same speed that he writes.”He is singlehandedly feeding hundreds of thousands of Brazilian readers--with a literary diet heavily weighted toward Westerns. A favorite by-line is "Tex Taylor." On his travels, Inoue, himself, has not been much farther into the American west than the West Side of Newark, NJ.

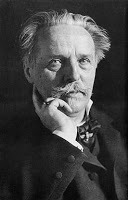

I'm reminded of Karl May--“a [German] adventure writer from the late nineteenth century

Karl Maywhom most Americans have never heard of but whose stories of the American West are to this day better known to Germans than the works of Thomas Mann. His books have sold more than a hundred million copies.” ("Whydo cowboys and Indians so captivate the country?" by Rivka Galchen. New Yorker, April 9, 2012

Karl Maywhom most Americans have never heard of but whose stories of the American West are to this day better known to Germans than the works of Thomas Mann. His books have sold more than a hundred million copies.” ("Whydo cowboys and Indians so captivate the country?" by Rivka Galchen. New Yorker, April 9, 2012 Among Karl May's hordes of youthful admirers were two boys destined to change the world--Adolf Hitler and Albert Einstein.

Published on May 06, 2013 19:08

April 28, 2013

A GOOD WRITER WHO KEEPS GETTING BETTER

Photo Credit: Marion EttlingerI’ve been a fan of T. Jefferson Parker since his 1985 best-selling debut splash with

Laguna Heat

. A fan and an admirer at the way he has steadily carved out his own distinctive niche in the SoCal mystery scene.

Photo Credit: Marion EttlingerI’ve been a fan of T. Jefferson Parker since his 1985 best-selling debut splash with

Laguna Heat

. A fan and an admirer at the way he has steadily carved out his own distinctive niche in the SoCal mystery scene.But I’ve had issues with Jeff, too—mainly teeth-grinding jealousy. See, I grew up in Laguna Beach (several decades before he arrived) and always figured I’dwrite the definitive Laguna mystery… someday. So much for fatuous daydreams. Jeff beat me to it—and kept right on going, while I’ve suffered from chronic novel-writing interruptus.

Yesterday at Vroman’s Bookstore in Pasadena I got a chance to say hello to Jeff again and congratulate him on his latest, his twentieth mystery novel,

The Famous and the Dead

. As trumpeted on the book’s jacket, the novel represents “The explosive conclusion to T. Jefferson Parker’s New York Times bestselling Charlie Hood series.”

Yesterday at Vroman’s Bookstore in Pasadena I got a chance to say hello to Jeff again and congratulate him on his latest, his twentieth mystery novel,

The Famous and the Dead

. As trumpeted on the book’s jacket, the novel represents “The explosive conclusion to T. Jefferson Parker’s New York Times bestselling Charlie Hood series.”In the more considered judgment of Jeff’s editor, The Famous and the Dead “might just be perfect.” This, at least, was the emailed verdict Jeff received in lieu of the editor’s customary pages of detailed notes on ways the story might be improved.

“What do you think?” the editor’s email ended, after apologizing for not finding any flaws in the work.

“Well, maybe so,” Jeff emailed back after thinking it over. He’d been braced for his usual intensive rewrite, but realized that, like the editor, he couldn’t think of any way to make the book better. “For what it is,” he told us at Vroman’s in his unassuming way, “I think it’s about as good as it can be.”

It’s never easy to write a good novel, let alone a “perfect” one. And the ending of this one was a particular challenge, he said, since The Famous and the Dead was the finale of the six-book series. There were more than a few loose ends, both accidental and deliberate, from the five previous Hood books, Jeff said. More significantly, like J.K. Rowling reaching closure on her magical saga with Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Jeff faced the daunting task of giving each of his main characters an appropriate final scene or curtain call. He also wanted to make sure each character got what he or she “deserved.”

It’s never easy to write a good novel, let alone a “perfect” one. And the ending of this one was a particular challenge, he said, since The Famous and the Dead was the finale of the six-book series. There were more than a few loose ends, both accidental and deliberate, from the five previous Hood books, Jeff said. More significantly, like J.K. Rowling reaching closure on her magical saga with Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Jeff faced the daunting task of giving each of his main characters an appropriate final scene or curtain call. He also wanted to make sure each character got what he or she “deserved.”Endings are always a big challenge, Jeff said. “I don’t like ambiguous endings. Like when people say, ‘Well, what do you think happened?’ To me those are always kind of a copout.”

The novelist’s challenge is to satisfy all story tendencies and meet all reader expectations, so that the coda, when it arrives, resounds with finality and inevitability. Like that old song lyric, “That’s all there is, there ain’t no more.” Or, in the more elegant words of Robert Frost: “The end implicit in the beginning but not foreknown.”

Before Jeff got around to signing copies, I asked him if he felt a sense of loss after saying goodbye to characters who’d been with him so long. I was thinking of Dickens who reportedly was almost inconsolable after closing the book on Copperfield; or theatrical wrap parties where actors celebrate a long and successful run, then go their separate ways like a family dispersed.

“Yes,” Jeff said. “I do miss Charlie Hood [and the others]. I mean, they’d been my daily companions for six books and six years of my life.”

“Yes,” Jeff said. “I do miss Charlie Hood [and the others]. I mean, they’d been my daily companions for six books and six years of my life.”The good news is, especially for any who have not yet sampled the Charlie Hood series, T. Jefferson Parker’s whole rowdy cast of characters is waiting to gather again for your reading pleasure. It starts with L.A. Outlaws .

Published on April 28, 2013 10:12

April 21, 2013

THRILLERBLOG AUTHOR INTERVIEW—G. J. BERGER

(I can’t imagine my life absent the inspiring magic of good stories and good storytellers. In fact, this blog is largely devoted to making an appropriate fuss over the yarn-spinners of yore. Through periodic author interviews, I also celebrate contemporary practitioners of this most magical of arts.--Dan Pollock)

On his website G. J. Berger recalls when, at the age of eight, “his mom told him the story of Hannibal crossing the Alps with elephants and a great army. He asked her what happened to Hannibal after that. Mom didn’t know, but he was hooked, had to find out, had to write about it.”

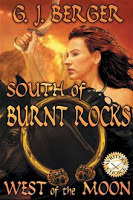

On his website G. J. Berger recalls when, at the age of eight, “his mom told him the story of Hannibal crossing the Alps with elephants and a great army. He asked her what happened to Hannibal after that. Mom didn’t know, but he was hooked, had to find out, had to write about it.”The result is a series of richly envisioned historical novels set in Roman times, full of adrenalizing adventure and the fascinating texture of daily life in another age. The first of these, South of Burnt Rocks – West of the Moon , tells the epic story of Lavena, a young Iberian-Celtic “she-warrior” who makes a stand against an invading Roman army.

The tale makes for about as exciting historical fiction as I can recall, with the kind of cinematic set-pieces I relish in the works of Rafael Sabatini and C. S. Forester. I use the term “cinematic” advisedly—Burnt Rocks has major big-screen potential; without too much tongue in cheek, I’d pitch it as Gladiator Meets Thelma and Louise.

The tale makes for about as exciting historical fiction as I can recall, with the kind of cinematic set-pieces I relish in the works of Rafael Sabatini and C. S. Forester. I use the term “cinematic” advisedly—Burnt Rocks has major big-screen potential; without too much tongue in cheek, I’d pitch it as Gladiator Meets Thelma and Louise.So let’s cut to the chase—my interview with G. J. Berger.

G. J. Berger in a reconstructed Iberian village.

G. J. Berger in a reconstructed Iberian village.D.P.: What about it? Have you thought of pitching your intrepid “she-warrior” to Hollywood? If not, why not?

G.J.: Others have said they see it as a movie. And that’s a common line among readers these days of almost any interesting fiction. We are much more a movie culture than book culture. I did not think of it as a movie while writing it. But I have heard writers say that script writing is good training for novel writing--helps in dialogue, scene setting and keeping a good pace.

D.P.: Whom do you see as your leading lady?

G.J.: I guess I’d need to search for Jennifer Lawrence’s younger sister..

D.P.: What led you to make your main character a girl?

G.J.: In 2008, I had a charming agent. After she sent my first historical off to editors, we mused about what next. I told her of my fascination with the tribal warriors who resisted the plundering might of Rome. She said, “Sure, but make your MC a woman. Far more women buy books about women than the other way around.” After a moment’s pause, I said, “I can make that work. I’ll write about his daughter.” And the main character is indeed the daughter of the tribal leader I had envisioned then.

D.P.: You have many strong women characters – exceptionally so. Will this be characteristic of the prequels and sequels in this saga you are telling?

G.J.: No, at least not intentionally. The prequel has one very strong female MC, but the hero is a boy who grows up fast.

D.P.: When you were a schoolboy, perhaps reading Caesar’s Commentaries, did your imagination take flight?

G.J.: I did not take Latin or read Caesar’s Commentaries. But I’ve always been drawn to works about powerful figures of the past—fictionalized or real. At age eleven, I devoured The Mutiny on the Bounty trilogy.

D.P.: What are some of your favorite source works for the Roman era?

G.J.: Translations of historical writings from back then. The work of Polybius has been helpful, though he was a Greek captured by Rome. There’s a wonderful series of "Daily Life" books by various authors on ancient people and places (India, Rome, Greece, etc.).

Australian writer Markus SuzakD.P.: What writers have influenced your writing most?

Australian writer Markus SuzakD.P.: What writers have influenced your writing most?G.J.: My mother, Markus Suzak, Jack London, Cormac McCarthy, Nikos Kazantzakis and others. Suzak says he tries to give the reader something special on every page. My mom, paraphrasing Goethe, said good writing “reaches into the full human life and grabs hold.” All men, I notice, with the notable exception of my mom. I must pick up one of the Twilight books or Fifty Shades of Gray—but then I wouldn’t have the foggiest what to do with it.

D.P.: Let's skate past that one. What books are you reading now?

G.J.: I recently finished

The Kiss

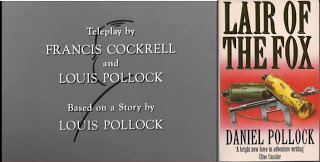

, a novel by poet Adrienne Silcock, which takes the reader on a journey of the soul as its four main characters discover who they are--and who they can never become. Then I read your

Lair of the Fox

, which wraps heroes and villains into an intense conflict straight out of a good James Bond film. In between those, I finished Grisham’s The Client.

G.J.: I recently finished

The Kiss

, a novel by poet Adrienne Silcock, which takes the reader on a journey of the soul as its four main characters discover who they are--and who they can never become. Then I read your

Lair of the Fox

, which wraps heroes and villains into an intense conflict straight out of a good James Bond film. In between those, I finished Grisham’s The Client. D.P.: Thanks for the plug—in fact, I’m definitely going to quote you. What other kinds of things do you read for pleasure?

G.J.: Sports Illustrated and almost anything. Good writing transports the reader to places, people and times without the reader’s awareness. I’m often surprised by fine writing and good stories previously unknown to me--and disappointed by best sellers.

D.P.: Do you write from a plot outline or do you prefer to let your characters lead you?

G.J.: I start with my main character in a specific place, about to do or experience something that I’ve been thinking about in all its details. I begin with the first few words. Those words push out the next. The last sentence I’ve written pushes out the next. The characters don’t lead me. For my historical novels the major events do frame my story and characters, and I try to stay true to the tides of history.

D.P.: When do you write?

G.J.: No set time.

D.P.: Do you log your daily output?

G.J.: Not in a direct sense. But I get antsy when I’m not on pace to complete the novel in roughly two years after the very first word. I have learned one trick to make each writing session productive. I try never to quit a writing session unless I’ve got the next sentence, paragraph or even scene in my head and ready to put to paper. That lets me open the computer in my next writing session and plunge ahead without staring at a blank screen.

D.P.: Great advice! How many hours does it usually take to make your daily output?

G.J.: My meter does not measure a daily output, though one good page a day, every day, is a worthy goal. That yields a close-to-finished novel in about one year.

D.P.: Do you research on the fly?

G.J.: For tiny details, yes. If I suddenly need to know how a farm implement works, I’ll research that as I go. For larger points—village life in times past, religious beliefs—I might spend months reading everything I can get my hands on before I dare write about it.

D.P.: How much time do you allot to marketing?

G.J.: No set amount of time. But my marketing senses are always on alert for opportunities to help other writers or to participate in conferences or groups. The best marketing for me has come from friends and other writers whom I have encouraged or perhaps helped on their way.

D.P.: Do you write in public (Starbucks, say) or strictly in private?

G.J.: I’ve never written in any public place—nor would I, unless I was writing a scene taking place at a Starbucks. For me, solitude works best for writing, a terribly selfish, reclusive and unfriendly endeavor.

D.P.: Do you write on more than one (fiction) project at a time? Can you juggle?

G.J.: I have bounced from project to project, but I don’t like to.

D.P.: Do you jump around in your narrative or write straight through?

G.J.: Straight through, but the very next sentence may cause a change 100 pages earlier, and I’ll go back and make the change as I go. In my recently published novel, the original beginning now sits about seventy pages in. I had to add more about the heroine’s young life before my original point of beginning, but that realization came after I was well into it.

D.P.: Have you always wanted to write?

G.J.: My single mom wrote as much as she could, and that made it easy and accepted for me to write at an early age. Later, I discovered that writing—any creative activity—is both fun and relaxing.

D.P.: Are there other genres you’d like to explore?

G.J.: Though my first published novel is a historical and the next likely will be another, my first finished novel was a psychological thriller. I expect that historicals and thrillers will fill up all my writing time.

D.P.: Thank you, G.J. Berger!

*

SOUTH OF BURNT ROCKS – WEST OF THE MOON (from G.J. Berger's website): "After three great wars, Rome has crushed Carthage. Now the undefended riches of Iberia beckon: gold, tin, olives, wine, and healthy young bodies to enslave. Burnt Rocks tells the story of Lavena, last child of the strongest remaining Iberian tribal leader at a time when Rome plunders and loots her land. Based on real characters and events, Burnt Rocks recreates that shadowy history."

Amazon(print & Kindle)

Smashwords

Barnes& Nole (print & Nook)

Kobo

About G. J. Berger: G. J. spent much of his young life on the road and at sea. often working as a crew member on a tramp steamer. Wherever his travels took him, old walls, canals, even storage holes deep in the ground, made him wonder about how they got there, about the people who built them, how they lived and got along.

When not writing, G. J. tries to roam around the places he writes about, likes to sit and soak up the times back then and bring them to modern life in his stories. G. J. is convinced that for all the changes in last 2000 years, people loved and hated, suffered and rejoiced, destroyed and built the same ways then as they do today.

Published on April 21, 2013 21:01

April 15, 2013

KEEP 'EM IN SUSPENSE

Looking back, I can see a certain predestination in my becoming a thriller writer. I’ve always loved the genre, for one. And my dad, the late Louis Pollock, was a skillful practitioner thereof. With two stubby fingers on his big black typewriter he hammered out several “ticking-clock” half-hour scripts for the old CBS Suspense radio show*—one of which Alfred Hitchcock selected and directed on his half-hour TV series, Alfred Hitchcock Presents.**

Looking back, I can see a certain predestination in my becoming a thriller writer. I’ve always loved the genre, for one. And my dad, the late Louis Pollock, was a skillful practitioner thereof. With two stubby fingers on his big black typewriter he hammered out several “ticking-clock” half-hour scripts for the old CBS Suspense radio show*—one of which Alfred Hitchcock selected and directed on his half-hour TV series, Alfred Hitchcock Presents.** But I took the long way around to Thrillerville. En route I tried my hand at all sorts of categorical fiction, from sword and sorcery (influenced by Robert “Conan” Howard), sci-fi (by Heinlein, Van Vogt, Sturgeon, among others), detectives and mysteries (from Sherlock to L.A. Noir), even an overwrought Harlequin romance (Riviera Concerto, unfinished, unfinishable). Somehow I missed YA.

But I took the long way around to Thrillerville. En route I tried my hand at all sorts of categorical fiction, from sword and sorcery (influenced by Robert “Conan” Howard), sci-fi (by Heinlein, Van Vogt, Sturgeon, among others), detectives and mysteries (from Sherlock to L.A. Noir), even an overwrought Harlequin romance (Riviera Concerto, unfinished, unfinishable). Somehow I missed YA.False starts and dead-ends, all. True, I didn’t know how to plot, but that’s another issue. None of these genres was a good fit for me. I could write passable short verse, but my ambitions remained novelistic.

My breakthrough, as I’ve mentioned before, was in confession stories, one of the remaining magazine short story markets back in the '70s. It was all about the trials and tribulations of young women—older teens, young marrieds, girls “in trouble.” I was ill suited for this niche, too, but succeeded, I suspect, because my submissions were actually suspense stories in drag.

Examples: “Can’t Anyone Hear Me Crying?” (True Story); “We Drove Into Disaster” (True Confessions).

Eventually and by default, I arrived at the pigeonhole where I felt most at home—suspense/thrillers. My struggles continued; the apprenticeship was long and bumpy, still is. But I like the terrain.

And suspense is not really a sub-category of fiction. It is primal and primary, embodying the essence of all good storytelling. I say “storytelling” because the oral tradition precedes the written. The tribal bard, way back into prehistory, earned his keep by capturing and holding an audience against stiff competition—an audience usually exhausted by the day’s labor.

An effective occupational imperative. Talk about "publish or perish." Spellbind your audience or quit the campfire for the cold.

An effective occupational imperative. Talk about "publish or perish." Spellbind your audience or quit the campfire for the cold.Scheherezade had to keep the Sultan desperate to hear the next installment in order to prolong her life one more night.

I’m reminded of the Jma ’el Fna, a huge square of beaten earth in the center of Marrakesh. It’s a meeting of ancient caravan routes, a legendary Arab-Berber swap-meet, little changed over the centuries. You can still wander the stalls, feasting on roasted mutton, and find snake charmers, sword-swallowers, letter-writers and teeth-pullers along with sellers of T-shirts and pirated jeans and DVDs, all competing for your coin.

Imagine, if you will, a tale-teller among them, practicing his craft in the age-old way. Enticing an audience, launching his tale, getting them “hooked,” stopping at a cliff-hanger, then making his circuit, hat in hand. If he’s good, the listeners will pay to hear the rest of the story. If they wander off to see the fire-eater, he'd better brush up on his technique.

Dickens had his readers so well and truly hooked that they crowded the New York City docks to meet the ship from London with the next magazine installment of Copperfieldor Old Curiosity Shop. Of course, it was not just Dickens’ plot predicaments that had them hanging. His characters were magically alive in his readers, in suspended animation, waiting to get their next lines.

And Dickens possessed another commodity rare in thrillerdom, and in modern fiction—narrative charm. Which goes back to storytelling ability. Scheherezade obviously had it. It’s a quality on display in every paragraph of Jane Austen, Robert Louis Stevenson, Arthur Conan Doyle and many other beloved storytellers.

“I feel that storytelling is the highest ambition of fiction,” thriller novelist AndrewKlavan said once in an interview with Publishers Weekly (6/12/95). “Authors are storytellers first and foremost.”

“I feel that storytelling is the highest ambition of fiction,” thriller novelist AndrewKlavan said once in an interview with Publishers Weekly (6/12/95). “Authors are storytellers first and foremost.”“It is just this power of holding the attention which forms the art of story-telling,” wrote Conan Doyle, “an art which may be developed and improved but cannot be imitated. It is the power of sympathy, the sense of the dramatic. There is no more capricious and indefinable quality. The professor in his study may have no trace of it, while the Irish nurse in the attic can draw out the very souls of his children with her words. It is imagination—and it is the power of conveying imagination.”

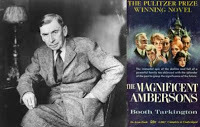

“Booth Tarkington (1869-1946) told a reporter that when he worked on a story, he imagined

that he was telling it to a man who had to catch a train in 20 minutes. The man was, of course, preoccupied with train-catching, impatient at being buttonholed and very suspicious of his narrator—in fact, almost certain that there would be no point to Tarkington's story... You see the precautions [Tarkington] took against lapsing even for a paragraph into any dependence on the reader's good will.” (Quoted by Gorham Munson in The Written Word, 1949, p. 20)

that he was telling it to a man who had to catch a train in 20 minutes. The man was, of course, preoccupied with train-catching, impatient at being buttonholed and very suspicious of his narrator—in fact, almost certain that there would be no point to Tarkington's story... You see the precautions [Tarkington] took against lapsing even for a paragraph into any dependence on the reader's good will.” (Quoted by Gorham Munson in The Written Word, 1949, p. 20)If readers were distracted in Tarkington's era, think how much more addlepated they are today. ADHD may be reaching epidemic proportions as our collective attentions are assaulted by digitized stimuli inbound on radio, TV, iPhone and computer screens, billboards and earbuds.

Charles "Chuck" BravermanThe besieged modern audience is attuned not to gradual narrative unfolding, but to instant visual and auditory overload. I trace the acute phase of this back to the ‘70s and Chuck Braverman’s “American Time Capsule.” This was supposedly a short “film,” but actually a linear mosaic of graphic images projected at epilepsy-inducing, stroboscopic speed, compressing two hundred years of American history into two and a half minutes.

Charles "Chuck" BravermanThe besieged modern audience is attuned not to gradual narrative unfolding, but to instant visual and auditory overload. I trace the acute phase of this back to the ‘70s and Chuck Braverman’s “American Time Capsule.” This was supposedly a short “film,” but actually a linear mosaic of graphic images projected at epilepsy-inducing, stroboscopic speed, compressing two hundred years of American history into two and a half minutes.No wonder many of us like to escape with a good book, or e-book, or audiobook (ah, the oral tradition!). Despite all the environmental static, the storyteller's task has not really changed from the day of the minstrel.

Jim PattersonAnd commercial thriller writing is storytelling at its most elemental. In the words of a modern best-selling minstrel, James Patterson: “What I want to do right now is write books that are satisfying to people who want to turn the pages.”

Jim PattersonAnd commercial thriller writing is storytelling at its most elemental. In the words of a modern best-selling minstrel, James Patterson: “What I want to do right now is write books that are satisfying to people who want to turn the pages.”“Why do we love suspense?" asked another such, John D. MacDonald. “The reader always wants to know what happens next, whether he's reading The Brothers Karamazov, David Copperfield or Hemingway.” (JDM, interview, Family Weekly, 5/5/85) _______________________________________________________________* “The Clock and the Rope” starring Jackie Cooper (12.5.47); “A Ring for Marya” starring Cornell Wilde (12.28.50); “Breakdown” (10.24.50)** “Breakdown” starring Joseph Cotton (11/13/1955).

Published on April 15, 2013 13:12