Aaron E. Carroll's Blog, page 38

June 16, 2021

Changes are coming to TIE

We’re going to be making some changes to TIE in the coming weeks and months. It’s nothing to get alarmed about. When we’re done, it’ll be the same type of content you’ve come to expect, just with a different look and feel. Everything will be better, or, at least, less mid-2000s.

But, to get from here to there, we need to shut down some things now and then and push out some test posts. Just bear with us, don’t unsubscribe or resubscribe to anything until I let you know it’s good to go. Don’t worry if you don’t get something by email you were expecting (if you’re an email subscriber). We’re watching and we’ll know what we’re breaking and we’ll fix it all, in time.

The post Changes are coming to TIE first appeared on The Incidental Economist.June 14, 2021

Association of Medicaid-Focused or Commercial Medicaid Managed Care Plan Type with Outpatient and Acute Care

Stuart Figueroa, MSW, is a policy analyst at Boston University School of Public Health. He tweets at @RealStuTweets.

Little is actually known about how variations in Medicaid managed care (private plan alternatives to traditional, fee-for-service Medicaid) translate to treatment utilization and health outcomes. The oft-cited advantage of managed care — that it promotes efficiency and cost savings while protecting against unnecessary or redundant treatment — is similarly scant of evidence. This evidence gap exists despite Medicaid’s significant enrollment, about 80 million, 70% of which is enrolled in a comprehensive managed care plans.

Managed care is big business, and is projected to only get bigger. In the Medicaid space, managed care plans claim an increasing market share as traditional fee-for-service enrollment dwindles.

Health insurance carriers point to the increase of state Medicaid dollars being directed to managed care, $281 billion (FY18) vs. $90 billion (FY10), as evidence of the value proposition of managed care: quality care, controlled costs. Plans are paid capitated rates (e.g., a per member per month amount) to provide a defined set of benefits, which provides the potential for cost control.

Managed care plans may be provided by an insurance carrier that primarily serves the Medicaid population (Medicaid-focused plan), or by a carrier that primarily offers commercial health insurance, typically for-profit (commercially-run plan). According to analysis from the Kaiser Family Foundation, six commercial carriers, all of which are publicly traded companies, account for more than 47% of all Medicaid managed care enrollment, nationally. The growing presence of commercially-run plans participating in managed care requires examination to ensure that such investments are both clinically and fiscally sound.

New Study

To date, there has been limited scholarship as to the differences between Medicaid-focused plans and commercially-run plans. Given their for-profit nature, there has been concern that commercially-run plans might implement administrative policies and practices to limit patient access to care in an effort to minimize costs and retain those savings as profit. In a new study published in JAMA Internal Medicine, researchers sought to bridge this gap by looking at how commercially-run Medicaid plans compared to Medicaid-focused plans relative to enrollee utilization of outpatient and acute care services.

(Authors and academic affiliations include Shailender Swaminathan, PhD, Krea University [Scricity, India], Brown University; Chima D. Ndumele, PhD, Yale School of Public Health; Sarah H. Gordon, PhD, Boston University School of Public Health Department of Health Law, Policy and Management; Yoojin Lee, MS, Brown University; and Amal N. Trivedi, MD, MPH, Brown University).

The researchers followed a cohort of Medicaid enrollees (n=8010), living in a state in the northeast, who were randomly assigned to two managed care plans after their previous managed care plan (a nationwide commercial plan) withdrew from the state’s Medicaid market. Affected enrollees were assigned at the family-level to either a Medicaid-focused plan or a commercially-run plan, effective January 1, 2011. The researchers followed the cohort for 30 months post-plan assignment to evaluate any association between health care utilization and managed care plan type. Outcomes of interest included outpatient visits, inclusive of primary care office visits (family practice, pediatrics, internal medicine, and women’s health services) and office visits to any specialty clinician type. Primary outcomes also included emergency department (ED) encounters, inpatient hospitalization, and ambulatory care-sensitive (ACS) admissions.

For its primary analysis, the study employed statistical analyses (chi-square for independence, independent samples t test, and t tests for differences in proportions) to assess baseline differences between the two enrollee groups. Linear regression models were also used as part of the analysis to estimate intent-to-treat association between the Medicaid-focused plan and the commercially-run plan.

Findings

The study found that those enrolled in the commercially-run plan received 22% more outpatient services versus those who were randomly assigned to the Medicaid-focused plan. Relative to the other outcomes measured (ED visits, ACS admissions, and hospitalizations), the study found no difference resulting from the random plan assignments. Perhaps most significantly, the increased utilization of outpatient services among commercially-run plan enrollees was associated with a 61% increase in the use of specialty care — an association that held regardless of enrollee demographics, chronic disease status, or Medicaid eligibility type.

Researchers identified two factors that might explain increase outpatient utilization in the commercial plan relative to the Medicaid-focused plan. First, the Medicaid-focused plan had a referral pattern that prioritized referrals to community health services (CHCs), a practice type associated with less intensive care encounters. CHCs are understood to offer robust primary care which may have mitigated the need for additional outpatient visits. The other factor identified was the association of specialty care visits. Researchers theorized that this may be the result of the commercially-run plan having a robust enrollment of specialty care providers, or simply that primary care visits were less intensive compared to those received in the Medicaid-focused plan.

Conclusion

The study acknowledges several limitations that may impact generalizability. Factors related to the state’s Medicaid managed care marketplace (e.g. plan availability, competition, and market share) may limit generalizability to other states. The researchers also had limited access to information as to how the different managed care plans were administered (e.g. provider network, prior authorization requirements, and utilization management procedures). It is possible that administrative differences could influence enrollee utilization. Lastly, the study did not include individuals who were dually enrolled in Medicaid and Medicare or those who made eligible through Medicaid expansion to non-disabled childless adults, limiting generalizability to these populations.

The study’s findings support the need for continued evaluation of managed care plans, both commercial and Medicaid-focused. While these results did not support the concern that access to care suffered within the commercially-run plan, the authors highlight that increased outpatient utilization was not associated with lower utilization of other levels of care such as inpatient admissions and ED visit. Further, the authors contend that enrollment in commercially-run plans may result in higher spending (e.g. future negotiation of capitated payments predicated on increased utilization) with no discernable improvement in health outcomes.

As the health care system continues to embrace managed care for its promise of efficiency, cost savings and containment, and reduction of waste, there is an economic imperative to ensure that managed care as a financing mechanism is truly effective. It is critically important that the managed care paradigm maximizes access to clinically appropriate care and demonstrates improved patient health outcomes.

The post Association of Medicaid-Focused or Commercial Medicaid Managed Care Plan Type with Outpatient and Acute Care first appeared on The Incidental Economist.June 10, 2021

Cancer Journal: A table of contents

I am a psychologist, a health services researcher, and a contributor to The Incidental Economist. The Cancer Journal reports my experiences as a cancer patient in the COVID pandemic.

“I have serious news.” My day and night in the Emergency Department on July 2nd and 3rd, 2020; in which I was first diagnosed with cancer. Playing for real money. In which I meet my tumour . I explain what kind of cancer I have, what likely caused it, and why having everyone vaccinated against the human papillomavirus matters, even for men. Treating cancer — So many decisions . There are difficult choices for treating cancer. Here’s how I made them. Not-so-shared cancer decision-making . How is treatment supposed to work when you can’t communicate with the Cancer Centre? Radiation Therapy for Cancer — What’s It Like? For one thing, they put you into a machine. Wearing a mask.Radiation therapy for cancer: Two weeks left. On what it’s like to be a cook who loses the ability to taste.Radiation therapy for cancer: DONE I’m through. With a health intervention from my dog.Fighting Cancer and Fighting COVID-19. Why I don’t ‘fight’ cancer. Hallway Medicine . I travel by ambulance to an Emergency Department and get treated in the hallway. Why that happens in Ontario.“So, how do you feel about having cancer during COVID?” The emotional cost of cancer.WTF, I have a lung tumour? In which I get to read the results of my CT scan online, before my doctor sees them. What is health? It’s not clear what ‘health’ means, but you need to get clear about it to make a good decision about your care.The PET Scan. I have another test to check whether radiation killed my tumour. And it suggests that the tumour is still there. How to Live with Cancer. Getting through with a good marriage, a good dog, and Peloton.Ontario on the Edge. How the pandemic is threatening our provincial health care system.SHATTERED. I get the results of a biopsy. My cancer is back and my prognosis is bad.Hard Conversations and Deep Attention. How do you have a conversation about dying? Immunotherapy. My search for a new treatment strategy.To get future Cancer Journal posts by email, sign up here.

@Bill_Gardner

The post Cancer Journal: A table of contents first appeared on The Incidental Economist.Covid Vaccine Month of Action

The Biden administration has announced a new a goal when it comes to Covid-19 vaccinations in the US: It aims for at least 70% of Americans to receive at least one dose by July 4th. The current administration has announced a plan and lots of companies are pitching in to help incentivize these efforts – so if you’ve been putting off vaccination, maybe this episode will help get you going!

The post Covid Vaccine Month of Action first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

June 9, 2021

The Proposed Hospital Mega-Merger in Rhode Island Shouldn’t Happen

The two largest hospital systems in Rhode Island, Lifespan and Care New England (CNE), submitted an application to the state in April to form a new health system in partnership with Brown University.* In spite of proponents’ claims to the contrary, this mega-merger would likely raise health care costs, wouldn’t meaningfully affect care quality, and would do nothing to keep care local.

The merger would likely raise health care costs

A robust body of evidence supports the idea that hospital mergers, regardless of the tax-exempt status of merging parties, generally raise commercial prices. This happens because hospitals with more market power have more leverage to charge health plans higher prices. Since a merged Lifespan-CNE system would control 68% of the acute care beds in the state if approved, its hospitals could (and would) demand ever-higher reimbursement from commercial payers.

To reassure policymakers, Lifespan, CNE, and Brown have pointed to state regulations that limit hospitals’ ability to increase the rates they charge commercial health insurers. These rate caps are undeniably a potent tool for containing health care costs. However, they do not prevent hospitals from driving up prices for services rendered to health plans regulated exclusively by the federal government under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA). Since ERISA-covered plans account for about 43% of the commercial insurance market in the state, the new hospital system could extract enormous profits using this loophole, which would raise premiums for thousands of Rhode Islanders.

The merger likely wouldn’t improve care quality or patients’ experiences

A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine last year found that hospital consolidation was not associated with significant differences in rates of mortality or hospital readmission. Worse, the study authors observed a statistically significant association between hospital mergers and lower-quality patient care experiences.

To be taken seriously, hospital systems hoping to consolidate should demonstrate what Harvard professors Leemore Dafny and Thomas Lee have called cognizable efficiencies. This means that promised gains in care quality or patient experiences need to be empirically measurable and likely to emerge. It also means that the onus is on hospital systems to explain why a merger is their only means of achieving better quality. Until Lifespan, CNE, and Brown University do just that (to date, they have not), Rhode Island policymakers should have little faith that quality improvements will materialize.

Hospital care can stay local without this transaction

For Rhode Island officials and patients alike, the potential economic and health-related dangers of outsourcing hospital care to Boston or New Haven are top of mind. When Partners HealthCare attempted to acquire CNE a few years ago, for example, the outcry was swift and emphatic. An editorial in the Providence Journal, entitled “The threat to R.I. health care,” ominously asked whether the Boston system was already “draining off Rhode Island patients.”

Contrary to what Lifespan, CNE, and Brown might claim, Rhode Islanders can keep their hospital care in-state without agreeing to this deal. Under the Hospital Conversions Act, the state’s Department of Health and Attorney General both have the power to veto hospital transactions that threaten Rhode Island health care. If a hospital system based in Connecticut or Massachusetts tries to acquire Lifespan or CNE down the line, state officials could unilaterally prevent such a deal under current law.

In any case, approving this merger will not prevent a consolidated Lifespan-CNE entity from attempting to merge with out-of-state systems in the future. In fact, it might be harder to prevent just that from happening, given the massive political influence that a merged Lifespan-CNE-Brown system would wield at the Rhode Island State House.

Conclusions

While the prospect of a world-class, locally based health system in Rhode Island may seem alluring at first, policymakers should block this merger.

At the federal level, the Federal Trade Commission should bring an action against this deal on the grounds that it would “substantially lessen competition.” At the state level, officials at the Rhode Island Department of Health and Attorney General should use their authority under the Hospital Conversions Act to reject this merger.

Rhode Islanders deserve world-class, local, and affordable hospital care. But this merger won’t help make that a reality. As Dr. Thomas Tsai and Dr. Ashish Jha, dean of the Brown University School of Public Health, wrote in JAMA in 2014, “Higher health care costs from decreased competition should not be the price society has to pay to receive high-quality health care.”

Research for this piece was supported by Arnold Ventures.

*Disclosure: I am currently an undergraduate student at Brown University. I also work for a research group, the Program On Regulation, Therapeutics, And Law (PORTAL) , which operates under the umbrella of Mass General Brigham. Formerly known as Partners HealthCare, Mass General Brigham signed an agreement to acquire Care New England in early 2018, though the Boston-based system backed out the following year.

The post The Proposed Hospital Mega-Merger in Rhode Island Shouldn’t Happen first appeared on The Incidental Economist.June 7, 2021

Buprenorphine Regulations and Better Treatment of Addiction

We face a lot of obstacles on the road to ending the opioid crisis, and one of them revolves around access to evidence-based addiction treatments. The X-waiver, a waiver physicians must obtain to prescribe the partial opioid agonist Buprenorphine, is one of them. New regulations have eased the requirements for this waiver, hopefully paving the way to further improvements.

The post Buprenorphine Regulations and Better Treatment of Addiction first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

June 4, 2021

Paid sick leave is a women’s health issue

Cecille Joan Avila is a policy analyst at Boston University School of Public Health. She tweets @cecilleavila.

Paid family and medical leave has been the main focus lately, but paid sick leave is equally important. I talk more about its importance and why it matters for women’s health in Prism:

[Paid sick leave] addresses those who hold up society but are often invisible. They are women and nonbinary folk, and especially those who either choose not to have children, or cannot bear the children they want. They are the women who care for family members in need at home after long days of caring for others in medical facilities. They are the women with no one to depend on but themselves, who still care for the needs of others by working hourly shifts at the grocery store or holding service industry jobs—deemed essential last year, but since forgotten.

Whether an individual has paid sick leave currently depends either on the state they reside in or their employer. Continuing without a federal paid sick leave policy will only serve to exacerbate pre-existing disparities, especially as the COVID-19 pandemic eases in parts of the United States. Read the full piece, here!

Research for this piece was supported by Arnold Ventures.

The post Paid sick leave is a women’s health issue first appeared on The Incidental Economist.June 3, 2021

Overdiagnosis and overtreatment: the provider perspective

Elsa Pearson, MPH, is a senior policy analyst at Boston University School of Public Health. She tweets at @epearsonbusph. Research for this piece was supported by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation.

Overdiagnosis and overtreatment are widespread practices in the US health care system. Providers feel pressure from patients to “do something” and to protect themselves against malpractice. Patients feel pressure to go along with whatever providers say is best.

None of this leads to better care quality or health outcomes.

Overdiagnosis is defined as the “detection of psuedodisease,” or disease that will never cause the patient any issues. Overtreatment is treatment that provides no benefit and may even harm the patient. I recently wrote about this from the patient perspective, providing anecdotes and tips for patients to better advocate for themselves. Now let’s look at it from the provider perspective. Here are a few stories from providers who felt pressured to order tests or treatments that weren’t necessary.

(Before going any further, it’s important to note that undertreatment is an equally serious concern. In particular, people of color often have to fight to get the attention and treatment they need from providers. The evidence of this is overwhelming.)

Kendra Allan, internal medicine physician assistant

A patient of mine hurt her hand. Based on my clinical assessment, she did not need any treatment beyond rest and ice and maybe some Tylenol. After explaining my recommendations, she requested opioid pain medication and an x-ray. I reiterated that both were unnecessary, but she was insistent. I ultimately ordered an x-ray which came back normal. Thankfully, we still avoided opioids.

Amy Dickey, pulmonologist/intensivist

I told a patient that I still wasn’t sure what was ailing him. “So, you’re telling me I just have to live with this?” he asked. That was not what I was saying, I told him, but I wasn’t going to start treatment until I had a firm diagnosis. I worry that some patients think there is a magic pill that fixes everything. Diagnosis takes time and treatment sometimes involves behavioral and lifestyle changes rather than medical intervention.

Andrew MacGinnitie, pediatric allergist/immunologist

I see many patients who suffer from chronic urticaria, or daily hives without a specific trigger. They are often convinced it is an allergic reaction (which is usually not true) and are insistent on allergy testing. It is sometimes difficult to convince them that testing is not actually necessary. I generally won’t test but do worry that some will go see another allergist because they are not satisfied with my care.

Pushing back against overdiagnosis and overtreatment needn’t pit providers against patients. Just as patients should advocate for themselves, providers should practice evidenced-based medicine.

Respect health literacy. Patients come to their providers with varying levels of health literacy. Kendra Allan, the physician assistant quoted above, notes that some patients want to know all the details of their diagnosis and treatment plan while others only want to know the bare minimum. Prioritize questions and discussion — treatment should not be a unilateral decision anyway — and learn to explain things on their level, be it with academic rigor or in simple language.

Look to educate. Patients are not meant to have all the answers; after all, they wouldn’t need a provider if they did. However, this puts the responsibility on providers to educate their patients on diagnoses and treatment options. Tayler Simmons, a neonatal physician assistant, argues it is more valuable in the long run to educate her patients and their families on why she is not pursuing a particular test or treatment than it is to simply appease them and provide unnecessary care. Education also gives patients more realistic expectations of what sickness and recovery will look like, she says.

Wait and see. Not all tests or treatments need to happen right away. Even the right treatment at the wrong time is still the wrong treatment. At best, this results in little to no benefit to the patient and, at worst, it actually harms her. If it’s not an emergency, providers should encourage “watchful waiting.” You can always order the test later.

Say no. Not all tests or treatments need to happen at all. Providers should be comfortable saying no when pressured to order unnecessary imaging studies, consults, or prescriptions. Allan reminds us that a provider’s first mission is to “do no harm.” Saying yes to tests and treatments that aren’t indicated contradicts this, even if the patient insists.

The American health care experience is full of unnecessary tests and treatments that provide minimal benefit to patients. New research in JAMA shows that receiving more of this “low-value care” isn’t associated with higher patient satisfaction either. Moving the needle on overdiagnosis and overtreatment will take time, but providers can do their part by thinking twice before placing orders.

The post Overdiagnosis and overtreatment: the provider perspective first appeared on The Incidental Economist.What if there was a way to detect fraud for SUD facilities?

The following is coauthored by Cecille Avila (@cecilleavila), Austin Frakt (@afrakt), and Melissa Garrido (@garridomelissa).

Millions of Americans struggle with substance use disorder, with estimates suggesting as many as 1 in 13 people needed treatment in 2018. Between high demand for services and lack of regulation, this is an area of health care already rife with predatory behavior. Substance use disorder fraud was a significant problem before the COVID-19 pandemic, and it could potentially get even worse.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), more individuals reported an increase in substance use during the COVID-19 pandemic, and overdose deaths have gone up significantly. Now that vaccination rates are increasing and social distancing measures are being lifted throughout the United States, well-intentioned individuals or concerned family members may view rehabilitation facilities or treatment centers as a logical next step to address some of these issues.

But it’s not as easy as Googling “substance use disorder rehab facility near me” to find treatment centers that can provide appropriate — or even genuine — treatment. The amount of fraudulent behavior that has occurred in the past decade can make it feel as if there are equal numbers of results for substance use disorder treatment facilities and horror stories.

In some cases, individuals have been sent out-of-state as part of elaborate and profitable patient brokering schemes that do not actually connect them to treatment. Some treatment facilities have profited off patients by overbilling for unnecessary drug tests. Treatment facilities with a known history of violations have continued to operate, resulting in the deaths of patients. In Florida, a man running sober homes was found to have coerced residents into prostitution.

Using news articles and publicly available legal filings, it might be possible to identify potential warning flags for facilities by looking at their websites or asking certain informational questions, such as:

What is included on a facility’s website? References to accreditation can indicate a facility has met certain standards set by an outside organization (i.e., the Joint Commission).What’s not included on a facility’s website? Does it omit what kind of treatment plans are provided?What treatments or services does the facility provide? Medication assisted treatment is evidence-based, but equine therapy is less so.Who is going to provide treatment? For example, are staff members named and licensed?Are there clear policies in case of emergency (i.e., overdose)?Is recovery guaranteed? (This is not possible for a facility to guarantee.)Is there any financial assistance offered to help offset paying for care at the facility? A sliding scale financial assistance payment model can be helpful but offers of being paid (in cash or in kind) should be viewed with skepticism.The list goes on, and it would be impossible for individuals to try and find answers for every facility in question in a reasonable amount of time. Perhaps what would be helpful is if there were an automated way — even a resource — that could guide people toward more trustworthy providers who offer appropriate addiction treatment.

How? One potential approach could be to use insurance claims data to identify patterns that suggest fraudulent activity. For example, suspicious behavior might be detected through unusual frequencies of procedures (i.e., drug tests, including urinalysis), unusual numbers of patient encounters per specific providers, potentially unnecessary treatments, unbundled lab tests (instead of billing under a single code), duplicate or multiple billing, or upcoding (billing for more expensive procedures).

However, flagging a single suspicious incident, such as high frequencies of tests or procedures, may reflect an overly cautious provider and not a fraudulent one. But perhaps a provider with a high rate of suspicious activities relative to its peers is more likely to be fraudulent. If nothing else, it could assist insurers, regulators, and law enforcement in focusing resources to scrutinize providers more likely to be engaged in illegal fraud.

While using claims data to detect fraud can be helpful, it’s not a perfect system. Claims data depends on what providers submit, so providers can get away with potentially problematic behavior if they don’t bill insurers for it. Patient kickbacks, in which individuals receive both indirect and direct incentives to refer patients to certain facilities, is a significant problem in this industry and does not generate claims data. Facilities that benefit from patient kickbacks without raising any other flags could remain undetected.

One challenge: An individual payor will only see or experience a subset of providers’ behavior. Perhaps a pattern of fraud can only be reliably detected by tracking providers across multiple payors.

Unfortunately, pooling data across insurers is difficult. Some data sets that do so (e.g., all-payer claims) do not identify providers, rendering them useless for the task. But a few resources exist that have data elements up to the task, such as those provided by FAIR Health or the Health Care Cost Institute, among others.

Of course, accessing data is just the first step. The next is to develop and validate an algorithm to identify more likely fraudulent providers. Doing so could help reduce unethical provider behavior.

While the COVID-19 pandemic dominated the news, the opioid epidemic did not fade away. Being able to connect individuals to appropriate and effective services is necessary to prevent even more harm from being done and without concern about falling victim to fraud.

Research for this piece was supported by Arnold Ventures.

The post What if there was a way to detect fraud for SUD facilities? first appeared on The Incidental Economist.June 2, 2021

Cancer Journal: Immunotherapy

At the end of April, I received an end-stage diagnosis for my throat cancer. What this means is that although there’s no certainty about when I will die, neither I nor my physicians see a likely path leading to a cure. That doesn’t mean that there is no hope. We are working on a new plan of treatment with immunotherapy. In this update, I will explain what immunotherapy does.

My cancer is an oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC).

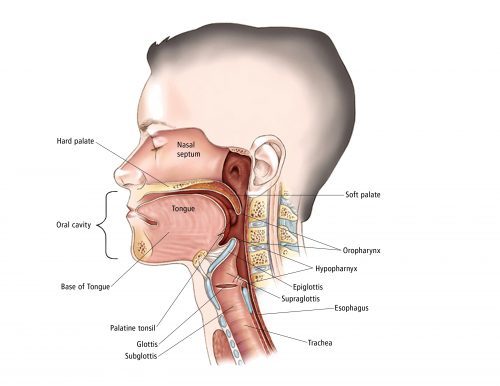

Anatomy of the head and neck.

The oropharynx is the region of the throat between the tongue and the epiglottis. In OSCC, the cells that line my throat in that region have started growing in an uncontrolled manner, forming a tumour.

The first line of treatment for OSCC is radiation, and it is usually curative. But unluckily for me, my tumour survived radiation and quickly recurred. It’s now a hard lump, visible on the right side of my neck, with an ulcer inside my throat. Why is a lump in my throat a problem? In order of increasing severity, here is what the tumour does.

First, I feel disfigured by the visible tumour. There is also pain, from the ulcer and because the tumour impinges on the nerves in my throat. The tumour is getting large enough to hinder my swallowing, which is already difficult because of the pain. I may have to go back to feeding through a tube. If the growth is unchecked, it will block my airway, although we can ‘fix’ that with a tracheotomy. Worst of all, a large tumour includes millions of cancer cells, and the more cells there are, the more likely it is that one or more will escape and seed metastatic tumours elsewhere in my body. These, as they grow, will shut down other body systems. This last process is what is most likely to kill me.

In short, if possible, we want to get this thing out of me!

Which is, of course, what cancer treatment is about. In essence, cancer can be treated with radiation, surgery, or medications. The 35 sessions of radiation I received last summer left my tumour unimpressed. More radiation would likely hurt me more than the tumour.

I could have throat surgery, and if the surgeon completely removed the tumour and its local metastases, that would likely cure me.

Unfortunately, my tumour is large and located at the centre of the base of my tongue. This means that the surgery would damage a great deal of tissue. I would likely lose my tongue and much of my larynx, so I would be unable to swallow or speak. The surgery would also damage my epiglottis, the flap of tissue that allows us to switch the throat from a tube delivering air to the lungs to one delivering food and water to the gut. If my epiglottis isn’t working, my lungs will get infected, leading to pneumonia. I would spend much of my post-surgery time in the hospital and I would likely die there.

Think about that: would you want to have to die in a hospital during COVID, possibly alone, and unable to talk to anyone about what is happening to you? Two surgeons have now walked me through the consequences of surgery. Neither hid his relief when I declined the procedure.

This leaves medication. Classical chemotherapies work by damaging the genes in the nuclei of cancer cells. The problem is that they hurt the rest of the body, too, just not as much. But recently, medical oncologists have been developing immunotherapies. The current plan is for me to start treatment with a drug called pembrolizumab.*

To explain how this drug works, let’s take a step back and ask why cancer happens. Cancer happens because something damages the machinery in a cell that regulates the cell’s reproduction, leading it to grow uncontrollably. But that’s not enough to produce a tumour. The tumour also needs to escape the body’s immune system.

The immune system’s T-cells fight microbial pathogens, and they also search for and destroy cancer cells. The T-cells are like the police. If you are a cell, so long as you don’t reproduce more than you are supposed to, then no one gets hurt.

Which is great, except that having armed patrols roaming the body poses its own danger. If the T-cells get too aggressive and start attacking normal body tissues, we have an autoimmune disease. To prevent this, the body has evolved mechanisms that can suppress the T-cells.

One of these is called the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway. PD-1 is a receptor protein on the surface of a T-cell for programmed cell death. It is an off-switch on the T-cell. If another cell can bind to this receptor using a protein called PD-L1, the T-cell kills itself.

But this, unfortunately, provides an opportunity that the tumour can exploit. If the tumour gets a mutation that allows it to express a lot of PD-L1, it can escape the T-cell police and continue its uncontrolled reproduction.

Here is where pembrolizumab comes in. The molecule prevents the tumour from using the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway to shut the T-cells down. If the drug can do this, the T-cells will attack the tumour, which sometimes just ‘melts away.’ Some people have reactions to the drug, including inflammations that might be caused by overactive T-cells. Fortunately, these side effects are typically much less severe than those of older chemotherapies.

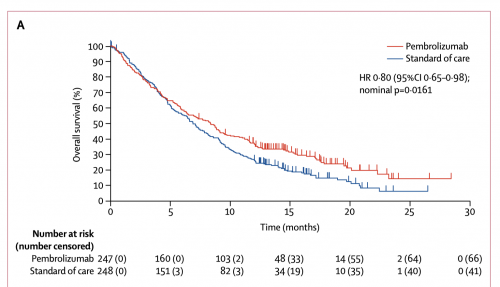

Sounds great, no? Well… here are the results from the KEYNOTE-048 trial, comparing pembrolizumab against the previous standard of care. The patients have recurrent head and neck cancer, like me. The horizontal axis is the time since the initiation of treatment. The vertical axis is the proportion of patients who are still alive at that time.

Survival curves: Pembrolizumab vs Cetuximab with chemotherapy.

Notice that half of the pembrolizumab patients are dead by 9 months. Pembrolizumab does better relative to standard care. But in absolute terms, the treatment doesn’t accomplish much.

Why doesn’t immunotherapy work better? My cute story above oversimplified the immune system. The system includes a zillion other mechanisms, an alphabet soup of pathways, each seemingly there to correct the malfunction of some other pathway. Here is an animation that illustrates how the immune system functions.

The immune system is a reductio argument against intelligent design: if it had a designer it must have been a committee of lunatic clockmakers, who spoke no common language. Immunotherapy doesn’t work that well because we don’t know what we are doing. You could not pay me enough to be an immunologist.

We are in an odd historical moment in oncology. On the one hand, we have enough data that I can foresee my life expectancy with some confidence. Twenty years ago, I couldn’t. On the other hand, we can’t reliably cure this disease. I hope my great-grandchildren will be shocked to learn that people used to die from cancer.

What matters, however, is the survival curve. Even with my best treatment option, I don’t have much time. So be it. That time is where the hope is. I need to think hard and make good choices about what to do with it.

*Where do these crazy drug names come from? There is actually a system to it (h/t, David States).

To read the Cancer Posts from the start, please begin here.

The post Cancer Journal: Immunotherapy first appeared on The Incidental Economist.Aaron E. Carroll's Blog

- Aaron E. Carroll's profile

- 42 followers