Aaron E. Carroll's Blog, page 37

June 30, 2021

Trends in Youth Exposure to Alcohol Advertising on Cable Television, United States, 2013–2018

Elsa Pearson, MPH, is a senior policy analyst at Boston University School of Public Health. She tweets at @epearsonbusph.

Alcohol advertising is pervasive in the US. From television to radio to billboards, we are bombarded with ads that promote drinking. What’s more, Americans, in fact, drink a lot. Both realities feed the narrative that alcohol holds a place of honor in American culture.

Federal regulation of alcohol advertising is quite minimal, due to protections under the First Amendment. Instead, the industry mostly relies on self-regulation. In particular, the industry is careful about youth exposure. The proportion of youth in the audience watching an alcohol advertisement cannot exceed the proportion of youth in the general population. As of the 2010 census, 28.4% of the general population is under the age of 21. Thus, 28.4% or less of the viewers of an alcohol ad must also be under 21. If this is true, the ad is considered compliant with industry standards.

Youth exposure to alcohol advertising is a known risk factor for underage drinking. But more research is needed to understand how often youth are exposed to these ads. From there, policy and public health experts can work to mitigate the relationship between the two.

Study design

In an effort to determine how frequently youth are exposed to alcohol advertising, researchers at the Boston University School of Public Health studied advertising data from 2013 to 2018. (Authors Elizabeth Henehan and Craig Ross are in the Epidemiology Department; David Jernigan is in the Department of Health Law, Policy, and Management.)

The authors used data from Nielson, an advertising measurement and data analytics company. These data included the per capita exposure to television alcohol advertisements by age and the date and time of the ads. The researchers chose to limit the study to cable television ads — based on previous research — and to exclude ads that promoted responsible drinking in some way. The authors then summed exposure by age group — 2-11 years, 12-17 years, and 18-20 years — and assessed changes over time. Exposure data from 2013 was used as a comparative baseline for all years through 2018.

Exposure to both compliant and noncompliant ads, per industry standards, was measured. Compliant alcohol advertisements are those for which less than 28.4% of the audience is under 21 years. Noncompliant ads are those for which more than 28.4% of the audience is underage.

Findings

The only group whose overall exposure to alcohol advertising increased from 2013 to 2018 was 2-11 years. Children aged 12-17 years and 18-20 years experienced a decrease in overall exposure. The proportion of ads that children were exposed to that were compliant increased for all age groups from 2013 to 2018, reaching nearly 100% for all groups. In other words, overall exposure to noncompliant ads decreased for all age groups.

The authors noted that trends in noncompliant and compliant exposure diverged by age group in 2015 and 2016, respectively. Because of this, they used those years as inflection points and compared exposure before and after (see figure 1 in the paper). From 2013 to 2015, exposure to noncompliant advertisements increased for the 2-11 years group and decreased for the other two groups. From 2015 to 2018, noncompliant exposure decreased for all age groups. From 2013 to 2016, exposure to compliant alcohol ads increased for the 2-11 years group and decreased for the other two age groups. From 2016 to 2018, compliant exposure decreased for all groups.

There are several study limitations. For one, accurate exposure data for young children requires that an adult in the home is accurately recording when children are watching television. (Neilson data rely on households to record who is watching TV when.) Another limitation is the data may generally overestimate exposure as many people may multitask while watching television or leave the room entirely while the set stays on. However, the study’s analyses may actually underestimate youth exposure because the authors chose not to include ads that promote responsible drinking in some way.

Impact

The study’s findings are encouraging, showing a general decrease in youth exposure to cable TV alcohol advertising, especially to noncompliant ads. However, the anomaly, the authors posit that the overall increase in exposure in the 2-11 years group could be occurring when these young children watch television with their parents/guardians, almost an unintentional exposure of sorts.

The researchers suggest that youth exposure could be reduced even further by modifying the industry standards of what constitutes compliant exposure. One way to do this would be to account for particular youth subpopulations within the total allowed proportion of underage viewers. For example, stating that children ages 2-11 years can only account for a specific percentage of the viewing audience could minimize their overall exposure to alcohol advertisements.

Exposure to alcohol advertising is a risk factor for underage drinking. As such, reducing exposure must be a key public health target. This study’s findings are reassuring that we’re making progress in the right direction.

The post Trends in Youth Exposure to Alcohol Advertising on Cable Television, United States, 2013–2018 first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

June 29, 2021

Cancer Journal – The Combined Positive Score

I have a bit of good news concerning my Combined Positive Score (CPS, although I have also seen Composite Proportion Score). The CPS is a biomarker that helps predict whether my current treatment regimen, immunotherapy, will succeed. This post will explain what the CPS is and why it matters.

Immunotherapy

Let’s review what immunotherapy is and how it works. Cancer is the uncontrolled growth of the body’s cells. The control has to break in at least two ways. First, something damages the machinery in a cell that regulates the cell’s reproduction. Second, the tumour also needs to escape the body’s immune system.

In the immune system, T-cells search for and destroy cancer cells. This is great, but if the T-cells get too aggressive and start attacking normal body tissues, we have an autoimmune disease. To prevent this, the body has evolved mechanisms that can suppress the T-cells.

The PD-1/PD-L1 pathway is one of these mechanisms. PD-1 is a receptor protein on the T-cell’s surface. It triggers programmed cell death; in effect, it’s an off-switch on the T-cell. If another cell can bind to this receptor using a protein called PD-L1, the T-cell kills itself.

Unfortunately, this pathway allows the tumour to evade the immune system. If the tumour gets a mutation that allows it to express a lot of PD-L1, it can suppress the T-cells. Then the tumour can continue its uncontrolled reproduction.

Here is where the immunotherapy drugs come in. I am taking pembrolizumab, a molecule that interrupts the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway. With the pathway broken, the T-cells can attack and shrink the tumour.

Sounds good, but unfortunately, the drug doesn’t work very often. In the first trial of pembrolizumab with recurrent head and neck cancer — like me — only 18% of patients responded to the drug. However, some of the responders had several years of remission (the period during which cancer stopped progressing). Averaged over all patients, the drug resulted in only 1.5 extra months of life. However, the better way to describe the results is that most patients didn’t benefit, but a few patients benefited a lot.

The Combined Positive Score

So why did the drug work in a few patients but not others? I’m not sure anyone really knows the answer. Still, there is some evidence that patients with high CPS values are more likely to be responders. The CPS estimates the proportion of tumour cells that express PD-L1, one of the molecules in the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway. The idea that tumours expressing a lot of PD-L1 would be most vulnerable to pembrolizumab makes sense. In any event, patients with CPS ≥ 20 were the best responders. And — drumroll, please! — on 2021-06-23, I learned that my CPS = 21!

This doesn’t mean that it’s certain that pembrolizumab will work for me. It’s a biomarker that may predict successful treatment; it’s not a measure of treatment success. It’s based on a limited amount of data. Many biomarkers that look promising in early studies fade as evidence accumulates. And even in those studies, some of those with high CPS values did poorly. If you have followed the Cancer Journal, you may recall that my tumour is p16+, a biomarker with lots of data that strongly predicts treatment success. And yet, my radiotherapy failed.

Where I’m At

So, I’m still facing daunting odds. But this is the first good news in months, and it strengthens my hope. It helps my resolution to eat well and maintain my workout discipline. Immunotherapy is unlikely to cure me. But I might have time to visit Tuscany again with my wife. And, perhaps, to finish my book.

To read the Cancer Journal from the start, please begin here.A table of contents for the Cancer Journal is here.To get the Cancer Journal in email, go here.The post Cancer Journal – The Combined Positive Score first appeared on The Incidental Economist.Reducing Administrative Costs in US Health Care: Assessing Single Payer and Its Alternatives

The following guest post is by David Scheinker, Barak Richman, Arnold Milstein, and Kevin Schulman.

Administrative costs in the US healthcare system are known to be higher than those in any other country, even than other countries with private health insurance systems. There also is widespread agreement the excessive US costs generate little, if any, value, and that they impose a tremendous burden on physicians. With administrative costs even for primary care services approaching $100,000 per year per physician, there is a growing recognition that reducing healthcare-related administrative costs is a policy priority.

Despite the longstanding concerns about these escalating costs, there is little understanding of what generates them and how we can reduce them. To the degree there has been any academic inquiry into administrative costs imposed on US providers, it has compared them to the much lower costs in other countries with nationalized systems. These comparisons are unflattering to the US system and are designed to encourage wholesale healthcare reform.

Our paper published in Health Services Research begins at the retail level, focusing on the specific administrative costs inflicted by our payment system on providers. We examine the complex contractual arrangements between insurers and physicians and measure the efforts that physicians must endure to get paid. It then offers a simulation model to estimate how certain policy reforms would result in nationwide administrative savings.

Currently, each health plan and each physician or physician group (and each hospital) negotiates over a contract for services on a periodic basis. Our analysis examines three separate costs that result from this type of market structure: architectural costs (the enormous number of contracts that are generated annually to provide services to patients), contractual complexity (the difficulty of following all of the requirements of each agreement to receive payment), and compliance costs (the costs of not following the rules in submitting a bill).

Based on this framework, we ask two questions: First, what if physicians entered into simpler contracts with insurers? And second, what if physicians (who accept patients with many kinds of insurance) agreed to a single boilerplate contract with all insurers rather than individualized contracts with each insurer? Put more simply, what if contracts were simpler and standardized?

Our simulation predicts that simplifying contracts would reduce billing costs by nearly 50%, standardizing contracts would reduce those costs by about 30%, and both simplifying and standardizing contracts would reduce those costs by over 60% percent.

We then used the model to estimate administrative cost savings from a single payer “Medicare-for-All” model. Consistent with claims made by advocates for nationalized health insurance, we estimate that a Medicare-for-All plan would reduce administrative costs between 33-53%, largely by standardizing contracts. But these cost savings are less than those generated from standardizing and simplifying contracts within our current system of private health insurance because we modeled that a Medicare-For-All plan would retain Medicare’s complex payment models and have increased compliance costs compared to private payers.

We think this is good news. Though we find that a single-payer system will reduce certain administrative costs, we also find that reforms to our current multi-payer system could generate at least as great a reduction. There might be benefits to pursuing national health reform, but we can reduce burdensome administrative costs through much simple and less disruptive paths. The even better news from this study is that we can now have a more precise understanding of where administrative costs arise in our health system, and we have the means to evaluate the effects of other kinds of reforms. Understanding is the prerequisite to reforming.

David Scheinker is Clinical Associate Professor of Pediatrics and Executive Director of Systems Design and Collaborative Research (SURF) at the Stanford Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital.

Barak Richman is the Bartlett Professor of Law and Business Administration at Duke University and a Visiting Scholar in the Department of Medicine at Stanford University. @BarakRichman

Arnold Milstein is Professor of Medicine at Stanford and directs the University’s Clinical Excellence Research Center.

Kevin Schulman is Professor of Medicine at the School of Medicine and Professor of Business (by courtesy) at the Graduate School of Business at Stanford University.

The post Reducing Administrative Costs in US Health Care: Assessing Single Payer and Its Alternatives first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

June 28, 2021

Change coming for email subscribers

If you subscribe to TIE by email (which you can do here), a big change is coming, but you shouldn’t be concerned. Here are the details:

Heretofore, you received your TIE emails of posts via feedburner, which Google is discontinuing at the end of the month.Therefore, henceforth, you will receive TIE emails via MailChimp.For a brief period, you may receive TIE emails both ways (feedburner and MailChimp). Do not worry, the feedburner one will shut off on its own.If you’re already signed up for TIE emails, you need do nothing. Your subscription has been transferred from feedburner to MailChimp.If you wish to unsubscribe, when you receive a MailChimp email, there will be a way to do so at the bottom.If something appears fishy to you, feel free to reach out and let me (Austin) know.Again, if you don’t get TIE posts by email, and you want to, sign up here.The post Change coming for email subscribers first appeared on The Incidental Economist.Cancer Journal: Citizenship in the Kingdom of Malady

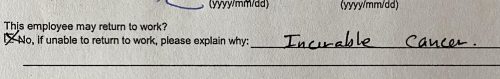

I’m fortunate to work for a hospital that provides excellent disability benefits (even in Canada, not all employers do). To qualify, I needed to get a form completed by my oncologist. Before I returned it to Human Resources, I read it.

The insurance form for my disability benefits.

There it is, concise and direct: “Incurable cancer.” The editor in me loves it, if no one else does. And no one would ever write it if they didn’t believe that it was true.

A pivotal scene in every cancer memoir is the event that leads to the initial diagnosis. Great writers on cancer describe it as a transition across a boundary.

Christopher Hitchens

Here is Christopher Hitchens reporting his discovery that he had esophageal cancer:

I have more than once in my time woken up feeling like death. But nothing prepared me for the early morning last June when I came to consciousness feeling as if I were actually shackled to my own corpse. The whole cave of my chest and thorax seemed to have been hollowed out and then refilled with slow-drying cement… It took strenuous effort for me to… summon the emergency services. They arrived with great dispatch and behaved with immense courtesy and professionalism. I had the time to wonder why they needed so many boots and helmets and so much heavy backup equipment, but now that I view the scene in retrospect I see it as a very gentle and firm deportation, taking me from the country of the well across the stark frontier that marks off the land of malady.

Annie Leibovitz’s photograph of Susan Sontag being transported to her cancer treatment.

Likewise, Susan Sontag:

Illness is the night side of life, a more onerous citizenship. Everyone who is born holds dual citizenship, in the kingdom of the well and in the kingdom of the sick. Although we all prefer to use the good passport, sooner or later each of us is obliged, at least for a spell, to identify ourselves as citizens of that other place.

The boundary between these kingdoms lies between you and me and between me and my former life. What is this boundary?

We in the Kingdom of Malady — specifically, the Duchy of End-Stage Cancer — have been through a transformative personal experience. We know things that you do not. The philosopher L. A. Paul argues that there are things that you cannot know until you experience them. Imagine that your parents raised you in a windowless room where everything was in black, white, or shades of grey. In this room, you learned to use the word ‘red.’ You might know many facts about redness, e.g., that apples are red. But until you saw a red apple and experienced redness, you wouldn’t understand ‘red.’ L. A. Paul:

[S]tories, testimony, and theory aren’t enough to teach you what it is like to have truly new types of experience — you learn what it is like by actually having an experience of this type.

Moreover, some of these experiences are personally transformative.

The sorts of experiences that can change who you are, in the sense of radically transforming your point of view… may include… having a traumatic accident, undergoing major surgery,… having a religious conversion, having a child,… or experiencing the death of a child.

If we do not know what these experiences are like, we can’t assign values to those experiences. How, then, can we make decisions that can lead us to outcomes we don’t understand? In the Duchy of Cancer, I have been offered surgery to remove my tumour, a procedure that would likely leave me unable to speak. I have no idea what being unable to talk would be like. Likewise, you have no idea what it’s like to live in a world structured by such choices.

What makes citizenship in the Duchy of Cancer a personally transformative experience? When you cross the border, at least four things happen. First, the sudden foreshortening of your life expectancy transforms how you experience time. Second, you have to suffer the disease and its treatments. The third is that death enters your room, and you have to address your fear of him. Fourth, being in the Kingdom of Malady transforms your relationships with citizens in the Kingdom of the Well. I’ll focus on each of these experiences in future posts, starting with how my sense of the future changed when that future got so much smaller.

However, if you need to experience cancer to understand it, then what is the point of the Cancer Journal? If Paul is correct, you won’t get it just from reading my words.

I hope that the Cancer Journal helps you when you cross the boundary. Paul is right: transformative life experiences take us places we cannot foresee. Yet somehow, literature takes me into the lives of people I can never be. I have experienced the flight of Hector around the walls of Troy, Nicodemus pinned by words in the night, Emma Bovary contemplating adultery, and Andrei Bolkonsky facing his duty before the battle of Borodino. Do I know what it is like to be wounded by shrapnel? Of course not. But having been there in imagination, I hope that I am more ready to learn how to face my own trial.

My goal, then, is to convey my experience to you even though, as Paul argues, I know that you can’t fully receive it. The Cancer Journal won’t provide anyone with self-help. (Except for me: I’m writing it to find my own way.) Your way to your fate will be different, but you might get some benefit watching me stumble toward mine.

If you know someone who has crossed the boundary, consider sending them a link to the Cancer Journal.

To read the Cancer Journal from the start, please begin here.A table of contents for the Cancer Journal is here.To get the Cancer Journal in email, go here.The post Cancer Journal: Citizenship in the Kingdom of Malady first appeared on The Incidental Economist.June 24, 2021

Does CBD Have Any Value as a Treatment?

Last week we covered CBD and mental health, finding that data to back up health claims are scarce and that consumer CBD products are often sketchy. In this week’s episode on CBD and other health ailments, we find that many of the same caveats apply.

The post Does CBD Have Any Value as a Treatment? first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

June 22, 2021

Test post #2: CBD and Mental Health

Cannabidiol, or CBD, is one of the most well-known components of marijuana and is not psychoactive like its THC counterpart. It has been touted as a treatment for almost any mental health  condition you can think of, but the overall evidence for this in humans is pretty scant. Beyond that, the evidence we do have suggests that effects are isolated to doses far higher than that seen in commercial products.

condition you can think of, but the overall evidence for this in humans is pretty scant. Beyond that, the evidence we do have suggests that effects are isolated to doses far higher than that seen in commercial products.

A systematic review and meta-analysis published towards the end of 2019 was only able to find a small handful of studies examining the effects of pharmaceutical grade CBD on mental health, and the majority of the evidence was rated as low quality. The authors were unable to find any RCTs on the effect of CBD on depression, ADHD, Tourette syndrome, or PTSD. They did include two studies on CBD and anxiety, finding no reduction of symptoms in individuals with an anxiety disorder.

In the realm of mental health, the bulk of CBD work has been conducted in relation to anxiety, and there is a small – but not robust – amount of evidence in favor of an effect.

………………………………….

The post Test post #2: CBD and Mental Health first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

Permanent expansions of government data collection will support policy innovation

This is a guest post by Will Raderman (@RadWill_), Alexandra Skinner (@alexskinnermph), and Julia Raifman (@JuliaRaifman). Will Raderman is a research fellow at Boston University School of Public Health. Alexandra Skinner is a research fellow at Boston University School of Public Health. Julia Raifman is an Assistant Professor at Boston University School of Public Health.

We rarely see the impact of policies reflected in data in real time. The COVID-19 pandemic changed that. In the present moment, a range of government, private, and academic sources catalogue household-level health and economic information to enable rapid policy analysis and response. To continue promoting periodic findings, identifying vulnerable populations, and maintaining a focus on public health, frequent national data collection needs to be improved and expanded permanently.

Knowledge accumulates over time, facilitating new advancements and advocacy. While mRNA biotechnology was not usable decades ago, years of public research helped unlock highly effective COVID-19 vaccines. The same can be true for advancing effective socioeconomic policies. More national, standardized data like the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey will accelerate progress. At the same time, there are significant issues with national data sources. For instance, COVID-19 data reported by the CDC faced notable quality issues and inconsistencies between states.

Policymakers can’t address problems that they don’t know exist. Researchers can’t identify problems and solutions without adequate data. We can better study how policies impact population health and inform legislative action with greater federal funding dedicated to wide-ranging, systematized population surveys.

Broader data collection enables more findings and policy development

Evidence-based research is at the core of effective policy action. Surveillance data indicates what problems families face, who is most affected, and which interventions can best promote health and economic well-being. These collections can inform policy responses by reporting information on the demographics disproportionately affected by socioeconomic disruptions. Race and ethnicity, age, gender, sexual orientation, household composition, and work occupation all provide valuable details on who has been left behind by past and present legislative choices.

Since March 2020, COVID-19 cases and deaths, changes in employment, and food and housing security have been tracked periodically with detailed demographic information through surveys like the Both cumulative statistical compilations and representative surveillance polling have been instrumental to analyses. Our team has recorded over 200 state-level policies in the COVID-19 US State Policy (CUSP) database to further research and journalistic investigations. We have learned a number of policy lessons, from the health protections of eviction moratoria to the food security benefits of social insurance expansions. Not to be forgotten is the importance of documented evidence to these insights.

Without this comprehensive tracking, it would be difficult to determine the number of evictions occurring despite active moratoria, what factors contribute to elevated risk of COVID-19, and the value of pandemic unemployment insurance programs in states. The wider number of direct and indirect health outcomes measured have bolstered our understanding of the suffering experienced by different demographic groups. These issues are receiving legislative attention, in no small part due to the broad statistical collection and subsequent analytical research on these topics.

Insufficient data results in inadequate understanding of policy issues

The more high-quality data there is, the better. With the state-level policies present in CUSP, our team and other research groups quantified the impact of larger unemployment insurance benefit sizes, greater minimum wages, mask mandates, and eviction freezes. These analyses have been utilized by state and federal officials. None would have been possible without increased data collection.

However, our policy investigations are constrained by the data availability and quality on state and federal government websites, which may be improved with stimulus funds allocated to modernize our public health data infrastructure. Some of the most consequential decision-making right now relates to vaccine distribution and administration, but it is difficult to disaggregate state-level statistics. Many states lack demographic information on vaccine recipients as well as those that have contracted or died from COVID-19. Even though racial disparities are present in COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths nationally, we can’t always determine the extent of these inequities locally. These present issues are a microcosm of pre-existing problems.

Data shortcomings present for years, in areas like occupational safety, are finally being spotlighted due to the pandemic. Minimal national and state workplace health data translated to insufficient COVID-19 surveillance in workplace settings. Studies that show essential workers are facing elevated risk of COVID-19 are often limited in scope to individual states or cities, largely due to the lack of usable and accessible data. More investment is needed going forward beyond the pandemic to better document a Otherwise there will continue to be serious blind spots in the ability to evaluate policy decisions, enforce better workplace standards, and hold leaders accountable for choices.

These are problems with a simple solution: collect more information. Now is not the time to eliminate valuable community surveys and aggregate compilations, but to expand on them. More comprehensive data will provide a spotlight on current and future legislative choices and improve the understanding of policies in new ways. It is our hope that are built upon and become the new norm.

Disclosure: Funding received from Robert Wood Johnson Foundation was used to develop the COVID-19 US State Policy Database.

The post Permanent expansions of government data collection will support policy innovation first appeared on The Incidental Economist.Rx vs. OTC (Part One): How Drugs Become Either Prescription or Over-the-Counter

Izabela Sadej, MSW, is a policy analyst at Boston University School of Public Health. She tweets at @IzzySadej. Research for this article was supported by Arnold Ventures.

Americans take a lot of medicine. From 2015 to 2016, approximately half of the U.S. population reported using at least one prescription drug in the past 30 days. However, many prefer over-the counter (OTC) drugs for various reasons, such as being simpler to obtain. Yet the process behind how medicines are classified as prescription vs. OTC and how they switch from one to the other is not so simple.

This post is the first in a series that examines how and why drugs are either prescription or OTC in the United States. Subsequent posts will explore the costs and benefits of prescription and OTC drugs for stakeholders and the role of pharmacists in drug distribution.

FDA Drug Classification Process

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) reviews and approves new drugs, including determining under which classification — prescription or OTC — they will be released. This process has evolved over the decades.

In 1951, the US passed the Durham-Humphrey amendment to the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, creating two classifications of drugs: prescription and nonprescription. Under the law, any drug that is deemed potentially habit-forming or harmful, and relatively unsafe for self-medication must be prescribed and supervised by a health care provider. This amendment also includes labeling requirements, stating that all drug labels must provide adequate instructions for use by the average person.

In 1962, the Kefauver–Harris amendment was added to the same law, which established a framework that requires drug manufacturers to scientifically prove that a medication is safe and effective. This is a key incentive for manufacturers to conduct clinical trials that assess the benefits and risks of their drugs.

There are currently over 100,000 marketed OTC drug products. Most of these drugs have reached the OTC market by satisfying the FDA’s monographs for OTC approval, a system that preapproves any drugs that contain active ingredients recognized as safe and effective for specific OTC uses such as: certain acne medications, antacids, cough and cold medications, hand sanitizers, laxatives, sunscreens, etc.

Drugs that fall outside the monograph qualifications, which are primarily new drugs submitted through New Drug Applications (NDA), almost always receive market approval to be prescription-only at first. In other words, there is a “prescription default” preference in the FDA approval system for new drugs.

Experts suggest that reversing this default to a presumption in favor of OTC status would promote patient autonomy. It would also align with a push by some for more medicines to be considered for the “Rx to OTC switch,” which has been relatively rare. An OTC presumption would require justification for a drug to be made prescription, increasing the likelihood of drugs being distributed as OTC from initial approval.

The Rx to OTC Switch

Though uncommon, drugs can switch from prescription to OTC. For example, azelastine hydrochloride (Astepro Allergy and Children’s Astepro Allergy nasal spray) is the most recent prescription to OTC switch in 2021. A drug can make this switch in two ways. One is through the “OTC drug review” — an ongoing FDA assessment of the safety and effectiveness of all nonprescription drugs as new information arises from petitioners (which can be from a Citizen’s Petition, from the drug manufacturer, or the FDA itself). The review process includes a panel of reviewers that determine whether some prescription ingredients are appropriate for OTC marketing. Another way is if the drug manufacturer submits an addendum to the original NDA, providing additional information that justifies a switch.

Whoever is advocating for the switch is responsible for developing the evidence that drives the approval process. There are three factors that the FDA must consider in order to approve the switch: a benefit-risk comparison, consumer-friendly labeling, and marketing considerations.

The benefit-risk comparison assess whether consumers will be able to safely reach the intended medical result. Medications always have some risks or side effects, but the switch to OTC focuses on the likelihood of risks to occur during consumer self-medication. Considerations include proper labeling that can be understood and adhered to, and the ability for consumers to properly diagnose their condition that the OTC drug would treat.For a drug to be used for self-treatment, the language on the label must be clear to minimize instances of unsafe dosages and administration.How the drug will be marketed to consumers must be considered. OTC drugs can be advertised differently than prescription drugs. There aren’t many legal advertising requirements for OTC products, with information being relayed directly from manufacturers to consumers, following regulations from the Federal Trade Commission.Accessibility to medicine is an essential part of an equitable healthcare system. While drug safety and precautionary measures are essential, patient autonomy is important too. The prescription vs. OTC decision trades the former off for the latter, to some extent. However, there are other approaches not used in the U.S. that strike a different balance, to be explored in a subsequent post in this series.

The post Rx vs. OTC (Part One): How Drugs Become Either Prescription or Over-the-Counter first appeared on The Incidental Economist.June 21, 2021

Test post #1: CBD and Mental Health

Cannabidiol, or CBD, is one of the most well-known components of marijuana and is not psychoactive like its THC counterpart. It has been touted as a treatment for almost any mental health  condition you can think of, but the overall evidence for this in humans is pretty scant. Beyond that, the evidence we do have suggests that effects are isolated to doses far higher than that seen in commercial products.

condition you can think of, but the overall evidence for this in humans is pretty scant. Beyond that, the evidence we do have suggests that effects are isolated to doses far higher than that seen in commercial products.

A systematic review and meta-analysis published towards the end of 2019 was only able to find a small handful of studies examining the effects of pharmaceutical grade CBD on mental health, and the majority of the evidence was rated as low quality. The authors were unable to find any RCTs on the effect of CBD on depression, ADHD, Tourette syndrome, or PTSD. They did include two studies on CBD and anxiety, finding no reduction of symptoms in individuals with an anxiety disorder.

In the realm of mental health, the bulk of CBD work has been conducted in relation to anxiety, and there is a small – but not robust – amount of evidence in favor of an effect.

………………………………….

The post Test post #1: CBD and Mental Health first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

Aaron E. Carroll's Blog

- Aaron E. Carroll's profile

- 42 followers