Aaron E. Carroll's Blog, page 36

July 30, 2021

Healthcare Triage Podcast: Covid Longhaulers and the Value of Online Conversation

In this episode, Dr. Natalie Lambert talks with Dr. Aaron Carroll about her research on COVID-19 long haulers, who experience symptoms for weeks or months after their initial diagnosis. They discuss COVID topics that are being overlooked in the media, and why online forums can inform valuable data for health care researchers to consider.

This Healthcare Triage podcast episode is co-sponsored by Indiana University School of Medicine, whose mission is to advance health in the state of Indiana and beyond by promoting innovation and excellence in education, research, and patient care, and the Indiana Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute, a three way partnership among Indiana University, Purdue University and the University of Notre Dame, striving to make Indiana a healthier state by empowering research through pilot funding, research education and training. More information on the Indiana CTSI can be found by visiting IndianaCTSI.org.

The post Healthcare Triage Podcast: Covid Longhaulers and the Value of Online Conversation first appeared on The Incidental Economist.Aduhelm is FDA Approved for Alzheimer’s, But Does it Work?

Alzheimer’s is a devastating disease that affects millions of people in the US alone, so there was a lot of excitement about recent news headlines of a drug approved to treat the disease. However, the approval was met with an outcry from several medical experts. In today’s episode, we talk about the data behind the drug and the why behind the controversy.

The post Aduhelm is FDA Approved for Alzheimer’s, But Does it Work? first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

July 29, 2021

Cancer Journal: A Soldier of the Great War

We construct life stories to present ourselves to the world, and the narratives we choose matter. A cancer memoir, like this one, tells a life story. So how does cancer figure in mine?

Part of the normative cultural frame for cancer memoirs is that cancer is an enemy. President Nixon declared war on Cancer. The Susan G. Komen Foundation has endlessly promoted the trope that breast cancer patients are fighters.

Komen Foundation merchandise.

More than once, when I have told friends about my diagnosis, they immediately responded, “You’re a fighter.” The phlebotomist who drew my blood this afternoon told me, unprompted, that “You are kicking cancer’s butt.”

These folks mean well, and I am grateful for their support. But in my story, I’m not fighting cancer. Why not?

First, ‘fighting’ isn’t a good metaphor for how I experience cancer. I have never been in combat, but I think I know the difference between fighting and receiving treatment.

I was once skiing a steep couloir in the Utah backcountry when the top layer of snow released, sending a foot of fresh powder rushing down the chute. If I fell, it would bury me. Somehow, I stayed upright on the flow until I reached the mouth of the couloir and could ski out of the path of the avalanche.

Another time, I capsized my kayak in rough water, 500+ meters from shore in a Nova Scotian fjord. Every time I tried to get back in the boat, the waves rolled me out again. I had enough sense to be wearing my wetsuit, but the water temperature was 7°C (45°F), and staying in it would have led to hypothermia. I tied my boat’s painter to a strap on my life jacket and sidestroked my way to shore.

In both cases, there were directly perceptible threats and physical struggles to survive. I recall my emotion during these events — not so much fear as the instant recognition of danger — followed by complete attention to and engagement in the tasks at hand.

Cancer treatment requires me to sit in a chair receiving a drug infusion. The drug binds to a receptor on the surfaces of the cancerous cells, enabling my immune system to attack the tumour. Of course, I can’t perceive any of this. I work on my laptop for an hour while the drug is pumped into my arm.

Are any of these people really fighters?

Second, cancer is a problem built into the heart of nature. How do I fight that? Let me explain.

Cancer is the breakdown of multicellularity. Humans are composites of ~30 trillion cooperating cells, with a division of labour constructed by evolution. One of the ways cells can violate this cooperation is by excessive reproduction. Athena Aktipis writes:

Cancer can be viewed as cheating within this cooperative multicellular system… cancer is characterized by the breakdown of the central features of cooperation that characterize multicellularity, including cheating in proliferation inhibition, cell death, division of labour, resource allocation, and extracellular environment maintenance.

Cheating is, of course, a metaphor; cells have no intentions. What cells have is genetic machinery that limits their reproduction to what your body needs. The immune system likewise polices the cells, attacking cancerous cells that reproduce too much. These controls maintain cellular cooperation. Why do these controls fail?

Cooperation fails because the body’s cells evolve. The maintenance of healthy tissue requires that about 2 trillion of the body’s tissues divide each day, which is hundreds of quadrillions of cell divisions over a lifetime. Each replication has a slight chance of a mutation. Given enough time, the chances are that the genetic machinery regulating cell reproduction will break somewhere in your body. We then get a population of cells with a heritable mutation that enables them to grow faster than their healthy neighbours, i.e., a tumour. In short, evolving multicellular organisms will suffer from cancer.† This is regrettable, but we wouldn’t have complex, sentient life without the evolution of multicellularity.

Cancer is woven deep in nature, but that doesn’t make it good or wholesome. It’s a terrible affliction, inflicting 9.5 million deaths globally each year, with an uncountable cost in suffering and the destruction of human capability. Although I can’t fight cancer as an individual, we have been fighting it as a species, albeit with only partial success. We have fought this war collectively across generations, and the weapon is science.

And here is my final point: I am not fighting cancer because cancer is not the true enemy. The enemies are death and suffering; cancer is just one of the myriad causes of affliction.

Albrecht Dürer. The Knight, Death, and the Devil. 1513.

My calling — what I do on the laptop while the drug flows into my arm — has been to serve on another front, researching mental illness. After developing cancer, I started writing for other patients about my experience. But caring for the other wounded is ancillary; research is the path to victory.

If you are a cancer patient and the fighter self-image empowers you, stay with it, and Godspeed. But be careful. A friend who is a palliative care physician tells me that the “fighting” metaphor can be devastating for his patients, particularly for males when they near death. Fighting is the master life story for a lot of men, but you can’t intimidate cancer. These men, he says, die experiencing themselves as losers.

That said, here is a warrior attitude that I aspire to. In September 1944, British paratroopers attempted to seize a bridge in a Dutch town deep behind German lines. Misled by faulty intelligence and planning, they were trapped by two far more heavily armed SS Panzer divisions. Lt. Colonel John Frost and Major Harry Carlyle commanded a small group of paratroopers who had seized one end of the bridge. They were surrounded and on the point of being overwhelmed. Then (as depicted in the film ‘A Bridge Too Far’), Carlyle and Frost watched a German officer approach under a flag of truce.

Maj. Carlyle: [To the German] That’s far enough! We can hear you from there! [To Lt. Col. Frost] Rather an interesting development, sir.

SS Panzer Officer: My general says there is no point in continuing this fighting! He is willing to discuss a surrender!

[Pause]

Frost: [To Carlyle] Tell him to go to hell.

Carlyle: [To the SS officer] We haven’t the proper facilities to take you all prisoner. Sorry!

SS Officer: [Confused] What?

Carlyle: We’d like to, but we can’t accept your surrender.

[Pause]

Carlyle: Was there anything else?

Carlyle’s pretense of misunderstanding the situation, and his deadpan delivery, communicated a complete indifference to his dire peril. His pretense of courtesy — “Was there anything else?” — cloaked but did not hide his contempt for the SS officer.

Although I need to accept that cancer is how things will likely end for me, humanity will continue to fight. We will win in the end.

*In a lecture, Stephen Jay Gould once said that,

Every damn story in biology has an exception. You give a talk and someone gets up in the audience and says, ‘Your theory is great. But there is this mouse found in Michigan…’

There seems to be an exception to my claim that cancer is the cost of multicellularity. Somehow, naked mole rats never get cancer. It’s okay; I would still rather be a human.

†Moreover, the continuing evolution of the tumour may be the process that kills me. For the sake of argument, let’s assume that my current immunotherapeutic treatments halt the progression of the tumour. However, if even a small population of cancerous cells survives, they will evolve. Eventually, these cells may evolve a novel way to defeat my immune system. Then the tumour will resume its exponential growth, leading to metastases and my death.

If you know someone who has cancer, consider sending them a link to this post.To read the Cancer Journal from the start, please begin here.A table of contents for the Cancer Journal is here.To get the Cancer Journal in email, subscribe here.The post Cancer Journal: A Soldier of the Great War first appeared on The Incidental Economist.July 28, 2021

Do Dates and Raspberry Leaf Tea Ease Labor and Delivery?

Pregnancy comes with a lot of advice concerning everything from how to determine the sex of the baby to how to ease both pregnancy symptoms and the oft-dreaded task of labor and delivery. Most of these stand on little to no evidence, but some are attached to data. In today’s episode, we examine the quality of the data behind two popular pieces of advice about easing labor and delivery outcomes.

The post Do Dates and Raspberry Leaf Tea Ease Labor and Delivery? first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

What’s Happening with Medicare Advantage and Why it Matters

Tasha McAbee (@tasha_mcabee) is an MPH student at Boston University School of Public Health.

For over 50 years, Medicare has provided affordable health insurance to hundreds of millions of people. At present, almost 62 million individuals depend on the public program to help cover the costs of medical services including hospitalizations, physician visits, prescription drugs, preventive services, and nursing facility or home health care.

But it doesn’t cover everything. Most Medicare beneficiaries rely on additional supplemental insurance beyond traditional Medicare. This additional insurance commonly consists of employer retiree benefits, privately purchased Medigap policies, or Medicaid for people with low income.

This is where Medicare Advantage comes in. Today, over 24 million Medicare recipients needing fuller coverage then what Medicare has to offer, instead enroll in more robust private plans obtained through Medicare Advantage. These managed care programs offer an expanded list of benefits at a fixed cost compared to Medicare, for which needed services may not be covered at all or come at a high price.

Growing pains

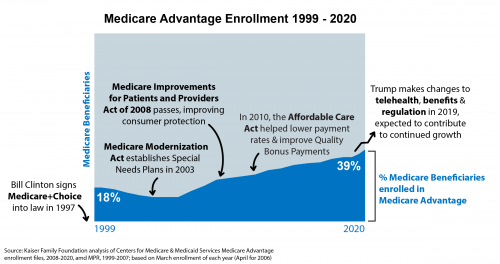

Enrollment in Medicare Advantage has rapidly grown since its implementation, from 18% of Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in 1999 to 39% in 2020. This growth, however, has not always been healthy.

Being a private market, Medicare Advantage plans behave differently than traditional Medicare. Any program, private or public, must maintain profit to stay afloat, but a number of Medicare Advantage plans were initially riddled with aggressive marketing tactics and lacked government oversight to protect consumers. Some companies hired revenue maximization experts, who went beyond ensuring earnings, and encouraged private insurers to engage in questionable marketing tactics that weren’t always in the best interest of the consumer. In the early days, a large number of beneficiaries were enrolled without a full understanding of the program or its disadvantages, and consumer satisfaction was low.

Government regulation eventually caught up, establishing means to curtail any predatory practices in Medicare Advantage marketing when the Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act was passed in 2008. The legislation strengthened government oversight over Medicare Advantage sales activities and consumer satisfaction has since improved, reaching a record 94% satisfaction in 2019.

Bipartisan support for the program continues to foster steady growth no matter the political party of the sitting president, but how much growth and whom that growth most benefits — consumer or insurer — depends on which policy levers that administration pulls.

Most recently, the Trump administration contributed to continued growth that potentially benefits both consumers and insurers. The Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) expanded the list of benefits covered by Medicare Advantage plans and made some telehealth services more available. However, Trump also took drastic steps to deregulate and further privatize the Medicare Advantage market. Perhaps most bluntly exemplified by 125 pages of rules for Medicare Advantage marketing and regulation being cut down to just 80 pages, weakening government oversight.

Further, the Trump administration failed to gain regulatory control over Medicare Advantage companies and their ability to alter risk adjustment scores, which determine the amount of money the federal government pays to subsidize the plans. The more control Medicare Advantage companies have over risk adjustment scores, the greater their potential ability to exaggerate the severity of a patient’s illness in order to maximize the amount of money they receive from the federal government. Inadequate auditing over risk adjustment not only allows for exploitation, but is a system that experts warn is “fatally flawed”, and has already resulted in several whistleblower lawsuits alleging risk adjustment fraud. When a Medicare Advantage plan over-withdraws funds from the federal government, it is more money drained from taxpayers and away from traditional Medicare needs.

Where to go from here…

The Biden administration is now left with the responsibility to manage continued growth while reining in the regulatory loosening that occurred under the prior administration. This administration should prioritize regaining regulatory control over risk adjustment practices and refocus policy decisions towards value-based care and consumer protection rather than policies that favor the facilitation of sales.

For example, although it may sound entirely beneficial to consumers that Trump expanded the list of benefits covered by Medicare Advantage plans, it can also be interpreted as a move to simply increase profit, especially if the value of these newly permissible services to the consumer cannot be demonstrated. The Biden administration will need to balance the complexities of private plans so that they best serve the public.

Medicare Advantage stands today as a more effective and stable program than when it was born. It is a powerful means for Medicare patients to get more value out of their spending and to maximize benefits. Moving forward, the government’s regulatory relationship with the program will need to ensure that as more people enroll, it doesn’t result in more consumers, or the government itself, being taken advantage of.

The post What’s Happening with Medicare Advantage and Why it Matters first appeared on The Incidental Economist.July 15, 2021

Ending the Campaign to Undo the ACA in the Courts

That’s the subhead of a new piece from me (gated, unfortunately) at the New England Journal of Medicine about the Supreme Court’s decision in California v. Texas. For a taste:

In an angry dissent, Justice Samuel Alito, joined by Justice Neil Gorsuch, accused the majority of making an “improbable rescue” of a defective law. In Alito’s view, the states had standing to sue not because they were harmed by the mandate directly, but because they were harmed by other parts of the ACA that are inextricably linked to the mandate. What’s more, Alito would have held not only that the mandate was unconstitutional, but also that the entire law was invalid. It is remarkable that two justices endorsed an outcome that would have plunged the U.S. health care system into chaos.

Because the Court decided the case on procedural grounds, not on its merits, Republicans might try to revive the case. In particular, the majority declined to address Alito’s argument supporting standing because it was “not directly argued by the plaintiffs in the courts below.” A new set of plaintiffs in a new lawsuit could conceivably make this argument. But Alito’s theory runs counter to the general thrust of standing law. Even if it were accepted, the majority’s decision rests on the premise that an unenforceable mandate has no real-world effects. It is hard to see how a mandate that does nothing is an essential part of the ACA, which strongly suggests that most of the justices believe the “shall” language could be severed from the law, while leaving the rest of it intact. Perhaps most important, the curt decision seems to signal that the Court wants nothing more to do with cases challenging the fundamental constitutionality of health care reform. …

But the broadside challenges to the law appear, finally, to have run their course. Would-be reformers — both conservatives who hope to dismantle the ACA and liberals who want to move beyond it — will have to look to Congress, not the judiciary, to achieve their goals. In a democracy, that is exactly as it should be.

If you’re keeping score at home, I initially discussed (and rejected) the standing-through-inseverability theory that forms the basis for Justice Alito’s dissent back in June 2018 at TIE. Later the same year in the Atlantic, I endorsed the standing theory that formed the basis for Justice Breyer’s majority opinion.

I’ll have more to say about the case in the coming weeks, but it’s a good outcome and I hope I’m right in my prediction that it marks the end of root-and-branch challenges to the ACA.

The post Ending the Campaign to Undo the ACA in the Courts first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

July 13, 2021

A Brief History of Pharmacy Benefit Managers (How They Became the “Shady Middle Men” in the Drug Market)

This is a guest post by Taylor J. Christensen, M.D. (@taylorjayc). Dr. Christensen is an internal medicine physician and health policy researcher with a background in business strategy and health services research.

Since any mystery in the healthcare system intrigues me, I’ve been working on understanding pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) lately.

Why did PBMs arise in the first place, and how did they come to have this somewhat strange role in the drug market? Let’s look at the evolution of PBMs, which I will categorize into three distinct phases.

Forewarning: There isn’t a lot of publicly available information on this stuff, so some of this is my best piecing together of things I’ve read plus supplemented by direct communications with people who work for insurers or PBMs.

Phase 1

Way back before PBMs, people used to pay for medications 100% up front out of pocket. They’d keep their receipts and then submit them all to their insurer later for partial reimbursement according to their insurance plan’s formulary.

That clearly had some downsides. If a patient couldn’t afford the full price up front, they would be stuck choosing which of their meds they’re not going to get, which is bad for both patients (nonadherence) and pharmacies (lost sales). Insurers also had to spend tons of time reconciling shoeboxes full of receipts.

If only there were a way to integrate an insurer’s formulary into the pharmacy’s computer system so that patients only pay their exact copay at the time they fill a prescription! Everyone would be a lot happier. Patients wouldn’t have to forego quite so many medications, pharmacies wouldn’t lose out on as many medication sales, and insurers wouldn’t have to deal with people sending in shoeboxes full of receipts. Win win win.

Enter the precursors to pharmacy benefit managers—they were essentially groups of software engineers tasked with working with pharmacies to get insurers’ formularies into the pharmacies’ computer systems. And they succeeded! After that, when a patient showed up to fill a prescription, the pharmacy would simply enter the patient’s insurance information into their system and the exact co-pay for that medicine would magically appear on the cash register’s screen. The patient paid their amount, and the transaction was then sent to the insurer to reimburse the rest.

But how did these precursor PBMs evolve into today’s PBMs that, among other things, “manage benefits”? My guess is that it went something like this . . .

Phase 2

These precursor PBMs got pretty good at integrating formularies into pharmacies’ systems, so they began to expand their customer base by helping lots of other insurers do the same thing.

Soon they became more familiar with all the complexities and intricacies of formularies than anyone else. And, as companies are wont to do, they leveraged that competency to make more money by offering a new service, which they maybe pitched to insurers like this: “Hey insurer, we already know all the details of your formulary. And we know where you could save money since formularies are kind of our thing. Why don’t you outsource your formulary-making efforts to us? We’ll make you a better formulary and charge less than it’s costing you to do it in-house right now. No-brainer, right?” And thus, not too long after their inception, PBMs officially started managing pharmacy benefits.

But that’s not where the story ends.

Phase 3 (dun dun dun)

Soon these PBMs found that they had amassed significant indirect control over which medicines patients get. Set a lower copay for a medicine and, sooner or later, more patients will end up taking it. And the one making the formulary is the one who sets the copays.

What did PBMs do with that power? They tried to leverage it to get better drug prices from manufacturers, which would allow them to offer an equivalent but cheaper formulary to their customers (insurers). But how, if they are not actually in the drug supply chain (that goes from drug manufacturers à drug wholesalers à pharmacies à patients) could they do that?

They cleverly reached out to the drug manufacturers directly and said something like this: “Hey drug manufacturer, we don’t actually have a direct financial relationship with you (yet). But we have significant control over how many sales you get because we set patients’ copays. How about we guarantee that your drug will, from now on, be the only one from its category in the lowest-copay tier? This will increase your sales quite a bit! And, in exchange for helping you get more sales, you can send us a “rebate” on every sale. So this is how it will work. We already keep track of every drug transaction, so every quarter we will send you the data to show how many patients using our formulary bought your drug, and you will send us a $10 rebate for each one.”

Contrary to popular belief, PBMs don’t keep all of this rebate money. Remember, their goal is to outbid other PBMs to offer the best formulary for the cheapest. And if the PBM market is competitive, they will have some degree of price competition that will force them to pass along some of those rebates on to their customers (insurers) in the form of lower fees.

I spoke with someone who works at an insurer and is in charge of contracting with their insurer’s PBM, and this person indicated that it is very possible for an insurer to get multiple bids from PBMs and identify which one is the best deal. Although, with the complexity involved, this process generally requires a specialist healthcare consultant who is an expert on navigating PBM contracts. I spoke with such a consultant, who had also worked for PBMs directly before becoming a consultant to insurers, and this person estimated that PBMs only keep about 20% of the rebates they receive from drug manufacturers. Other studies have been done on this topic, but attribution is tricky since PBMs are able to rename the monies they are receiving from drug manufacturers to fudge the numbers, which is probably why the Government Accountability Office reported in 2019 that PBMs only retain about 1% of rebates.

Well, there you have it. Phase 3 was the start of all the wheeling-dealing complexities that give PBMs their shady reputation.

I believe this is helpful background to have when you’re trying to improve the drug market (i.e., solve the problem of expensive drugs) because without understanding the incentives of the parties involved, you cannot get to the root of the problems with that system.

The post A Brief History of Pharmacy Benefit Managers (How They Became the “Shady Middle Men” in the Drug Market) first appeared on The Incidental Economist.Cancer Journal: The Sad Thing About Good News

This post has good news about my treatment. But in cancer, even good news can pose a challenge.

To appreciate how good the news is, let’s go back to April 2021 and the meeting with my surgeon when I learned that my neck cancer was recurrent. He gave me an end-stage prognosis with a life expectancy in months, not years.

Since then, I have started treatment with an immunotherapeutic drug, pembrolizumab. This did not, in and of itself, change my life expectancy much. The clinical trials data show that only about 1 in 5 patients with recurrent head and neck cancers respond to this drug. And please note: ‘response’ rarely if ever means ‘cure.’ Successful immunotherapy would likely be a few years of remission, followed by another and likely fatal recurrence. But relative to how things looked in April, that would be wonderful.

However, a piece of good news is that I have a biomarker that puts me in the group most likely to benefit from immunotherapy. And here is even better news: five weeks into treatment, I have experienced a significant drop in pain. It’s been two weeks since I have had to take hydromorphone, the powerful painkiller I was previously taking every four hours. I haven’t taken any pain medications today, which means that the ulcer on the inside of my throat has healed. And I have regained 5 of the nearly 60 pounds that I had lost since my diagnosis. All this suggests that I am one of the 1 in 5 recurrent head and neck cancer patients who will experience a remission with pembrolizumab.

And yet, despite this good news, my mood crashed. For a few days, I felt pinned to the couch by dread and loss. I was feeling physically better and psychologically worse than I have felt in 18 months. What was this about?

I have had a diagnosis of major depressive disorder since I was an adolescent. A few days of sadness isn’t depression — depression is a state that persists for weeks — but this felt like a preliminary tremor to an episode. Why should it flare now?

There are too many possible explanations.

First, I could be feeling depressed because cancer may be a cause of depression. Half of all cancer patients have mental health concerns (this also happens to patients with many other serious illnesses). Cancer hammers numerous body systems, including the brain. Caring for yourself with cancer is challenging under the best of circumstances. I cannot imagine how difficult it would be if I experienced a prolonged depressive episode.

Could depressed patients be more likely to develop cancer? The evidence here is less convincing. Still, there might be some physiological cause that can predispose us to develop both depression and cancer. I have previously discussed how cancerous cells must defeat the immune system for a tumour to develop. Depression is associated with disruption of the hormonal cycles related to our circadian rhythms and our responses to threat or stress. These hormones have complicated and profound effects on the immune system. Some theorists hypothesize that problems in the immune system may cause depression. So perhaps immune system dysregulation can increase your risk of developing both depression and cancer.

Finally, perhaps my twinge of depression was the result of the new medication. Pembrolizumab belongs to a class of drugs called monoclonal antibodies (that’s what the final ‘mab’ syllable refers to). The drug works — when it does — through its impact on the immune system. As noted, depression is associated with dysregulation of the immune system. There is evidence that other monoclonal antibodies can trigger depression. So perhaps this brief depression was a side effect of the new treatment: maybe pembrolizumab is changing my immune system in a way that triggers depression.

Given all these possible explanations, it is impossible to identify the specific cause of my mood swing. Obsessing about it will accomplish nothing.

Moreover, it distracts me from a more important question. In the best case, immunotherapy is likely to deliver me just a few years of remission. Yes, this would be fantastic. But it’s much less time than I thought I had before my cancer was diagnosed.

Therefore, I’m focused on this question: what should I do with the limited time I may have?

That’s too big a question for this post. What I want to talk about now is, what role should my emotions play in deliberating on how to spend my remaining life?

In my cancer journey, I’ve kept a tight grip on my feelings. The other challenges in your life don’t go away just because you develop cancer. You still have to cope. As the U.S. Marines say, SITFU (Suck It The Fuck Up). On this point, the Marines stand at the pinnacle of the Western tradition.

Plato and Aristotle. Detail from Raphael’s ‘School of Athens.’

Here is Plato, in The Republic, Book 10 604b-d:

Socrates: “it is best to keep quiet as far as possible in calamity and not to chafe and repine, because… it advantages us nothing to take them hard and our grieving checks the very thing we need to come to our aid as quickly as possible in such case.”

Adeimantus: “What thing do you mean?”

Socrates: “To deliberate about what has happened to us, and… to determine the movements of our affairs… in the way that reason indicates would be the best, and, instead of stumbling like children… and wasting the time in wailing, And shall we not say that the part of us that leads us to dwell… on our suffering and impels us to lamentation… is the irrational and idle part of us, the associate of cowardice?

There is wisdom in this. But I question Socrates’ view that in calamity, the emotions are forces of cowardice and immaturity that need to be quelled to clear the ground for proper deliberation. Emotions are more than just the passions that disable or motivate us. Emotions are part of how we perceive value in the world, how we appraise what matters for our well-being.

What is the appropriate response to a cancer diagnosis? It’s more than just having the belief that things are bad. If you haven’t registered your situation in your gut and your limbic system, do you fully understand it? Have you honestly faced where you are? We can, of course, be in error in our emotional perceptions, but the same is true about our vision. Even when our eyes deceive us, we do not pluck them out.

Martha Nussbaum writes that,

Instead of viewing morality as a system of principles to be grasped by the detached intellect, and emotions as motivations that either support or subvert our choice to act according to principle, we [should] consider emotions as part… of the system of ethical reasoning.

In deliberating about what I should do with the time I have left, I shouldn’t suppress my emotions. To intelligently discern my best course of action, I need to understand what matters to me, and part of that is sorting out how I feel about where I am. I’ve got cancer: It’s ok to let the sadness rip.

When I framed my grieving as depression, I pathologized it. Don’t get me wrong: If I need to, I will go back to psychotherapy. But there’s nothing irrational about being deeply sad about cancer. I’d worry more if I didn’t feel that way.

In the first weeks of immunotherapy, my health surged and revived my hope. But having hope gave me something to lose. Paradoxically, it was easier to be The Hard Guy when I thought there was only darkness ahead. Now there is some light, and I can loosen my grip. But in that light, I see my forthcoming loss more clearly.

So be it. My grief helps illuminate what is most valuable in my life, and this is the light in which I should deliberate.

If you know someone who has cancer, consider sending them a link to this post.To read the Cancer Journal from the start, please begin here.A table of contents for the Cancer Journal is here.To get the Cancer Journal in email, subscribe here.The post Cancer Journal: The Sad Thing About Good News first appeared on The Incidental Economist.July 2, 2021

Socioeconomic Disparity and Inequality Even Extend to Breathing

Individuals with higher socioeconomic status may enjoy a longer life, but we haven’t precisely pinned down all the reasons why. Disparities in lung function may help explain the lifespan gap between the poorest and richest Americans, and in today’s episode we cover a recent study on that proposed association.

The post Socioeconomic Disparity and Inequality Even Extend to Breathing first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

July 1, 2021

Recent publications from Boston University’s Department of Health Law, Policy and Management: July 2021 Edition

Below are recent publications from me and my colleagues from Boston University’s Department of Health Law, Policy and Management. You can find all posts in this series here.

July 2021 Edition

Blok AC, Anderson E, Swamy L, Mohr DC. Comparing Nurse Leader and Manager Perceptions of and Strategies for Nurse Engagement; A Qualitative Analysis. J Nurs Manag. 2021 Mar 08. PMID: 33683777.

Bolton RE, Bokhour BG, Dvorin K, Wu J, Elwy AR, Charns M, Taylor SL. Garnering Support for Complementary and Integrative Health Implementation: A Qualitative Study of VA Healthcare Organization Leaders. J Altern Complement Med. 2021 Mar; 27(S1):S81-S88. PMID: 33788605.

Charns MP. Limitations to National Policy and Financial Incentives: The Role of Organizational Dynamics. Med Care. 2021 Mar 1;59(3):193-194PMID: 33560764.

Domecq JP, Lal A, Sheldrick CR, Kumar VK, Boman K, Bolesta S, Bansal V, Harhay MO, Garcia MA, Kaufman M, Danesh V, Cheruku S, Banner-Goodspeed VM, Anderson HL, Milligan PS, Denson JL, St Hill CA, Dodd KW, Martin GS, Gajic O, Walkey AJ, Kashyap R. Outcomes of Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 Receiving Organ Support Therapies: The International Viral Infection and Respiratory Illness Universal Study Registry. Crit Care Med. 2021 03 01; 49(3):437-448. PMID: 33555777.

Enggasser JL, Livingston NA, Ameral V, Brief DJ, Rubin A, Helmuth E, Roy M, Solhan M, Litwack S, Rosenbloom D, Keane TM. Public implementation of a web-based program for veterans with risky alcohol use and PTSD: A RE-AIM evaluation of VetChange. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2021 Mar; 122:108242. PMID: 33509419.

Falvey SE, Hahn SL, Anderson OS, Lipson SK, Sonneville KR. Diagnosis of Eating Disorders Among College Students: A Comparison of Military and Civilian Students. Mil Med. 2021 Mar 04. PMID: 33686412.

Garcia MA, Rampon GL, Doros G, Jia S, Jagan N, Gillmeyer K, Berical A, Hudspeth J, Ieong M, Modzelewski KL, Schechter-Perkins EM, Ross CS, Rucci JM, Simpson S, Walkey AJ, Bosch NA. Rationale and Design of the Awake Prone Position for Early Hypoxemia in COVID-19 (APPEX-19) Study Protocol. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2021 Mar 01. PMID: 33647225.

Hadland SE, Bagley SM, Gai MJ, Earlywine JJ, Schoenberger SF, Morgan JR, Barocas JA. Opioid Use Disorder and Overdose Among Youth Following an Initial Opioid Prescription. Addiction. 2021 Mar 19. PMID: 33739476.

Hwang U, Dresden SM, Vargas-Torres C, Kang R, Garrido MM, Loo G, Sze J, Cruz D, Richardson LD, Adams J, Aldeen A, Baumlin KM, Courtney DM, Gravenor S, Grudzen CR, Nimo G, Zhu CW. Association of a Geriatric Emergency Department Innovation Program With Cost Outcomes Among Medicare Beneficiaries. JAMA Netw Open. 2021 Mar 01; 4(3):e2037334. PMID: 33646311.

Li M, Wang Y, Ndiwane N, Orner MB, Palacios N, Mittler B, Berlowitz D, Kazis LE, Xia W. The association of COVID-19 occurrence and severity with the use of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin-II receptor blockers in patients with hypertension. PLoS One. 2021; 16(3):e0248652. PMID: 33735262.

Lipson SK, Phillips MV, Winquist N, Eisenberg D, Lattie EG. Mental Health Conditions Among Community College Students: A National Study of Prevalence and Use of Treatment Services. Psychiatr Serv. 2021 Mar 04; appips202000437. PMID: 33657842.

Mackie TI, Schaefer AJ, Hyde JK, Leslie LK, Bosk EA, Fishman B, Sheldrick RC. The decision sampling framework: a methodological approach to investigate evidence use in policy and programmatic innovation. Implement Sci. 2021 Mar 11; 16(1):24. PMID: 33706785.

Morgan JR, Savinkina A, Pires Dos Santos AG, Xue Z, Shilton S, Linas B. HCV Viral Load Greater Than 1000 IU/ml at Time of Virologic Failure in Direct-Acting Antiviral-Treated Patients. Adv Ther. 2021 Mar; 38(3):1690-1700. PMID: 33590445.

Neufeld MY, Kimball S, Stein AB, Crosby SS. Forensic evaluation of alleged wrist restraint/handcuff injuries in survivors of torture utilizing the Istanbul Protocol. Int J Legal Med. 2021 Mar;135, 583–590. PMID: 33409560.

Peracca SB, Fonseca A, Hines A, King HA, Grenga AM, Jackson GL, Whited JD, Chapman JG, Lamkin R, Mohr DC, Gifford A, Weinstock MA, Oh DH. Implementation of Mobile Teledermatology: Challenges and Opportunities. Telemed J E Health. 2021 Mar 01. Online ahead of print. PMID: 33691074.

Shafer PR, Hoagland A, Hsu HE. Trends in Well-Child Visits With Out-of-Pocket Costs in the US Before and After the Affordable Care Act. JAMA Netw Open. 2021 Mar 01; 4(3):e211248. PMID: 33710285.

Sinaiko AD, Hayes M, Kingsdale J, Peltz A, Galbraith AA. Understanding Consumer Experiences and Insurance Outcomes Following Plan Disenrollment in the Nongroup Insurance Market. Med Care Res Rev. 2021 Mar 16; 1077558721998910. PMID: 33724071.

Spencer AE, Oblath R, Sheldrick RC, Ng LC, Silverstein M, Garg A. Social Determinants of Health and ADHD Symptoms in Preschool-Age Children. J Atten Disord. 2021 Mar 01; 1087054721996458. PMID: 33641514.

Trangenstein PJ, Whitehill JM, Jenkins MC, Jernigan DH, Moreno MA. Cannabis Marketing and Problematic Cannabis Use Among Adolescents. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2021 Mar; 82(2):288-296. PMID: 33823976.

Wang RY, Rojo MC, Crosby SS, Rajabiun S. Examining the Impact of Restrictive Federal Immigration Policies on Healthcare Access: Perspectives from Immigrant Patients across an Urban Safety-Net Hospital. J Immigr Minor Health. 2021 Mar 12. PMID: 33710446.

The post Recent publications from Boston University’s Department of Health Law, Policy and Management: July 2021 Edition first appeared on The Incidental Economist.Aaron E. Carroll's Blog

- Aaron E. Carroll's profile

- 42 followers