Aaron E. Carroll's Blog, page 34

September 9, 2021

The Research on Ivermectin and Covid-19

Interest in the antiparasitic drug Ivermectin has increased drastically as of late thanks to the belief that it can help to prevent and/or treat Covid-19. In today’s episode we examine recent data on the efficacy of Ivermectin as an antiviral and discuss the history behind how it gained this reputation.

The post The Research on Ivermectin and Covid-19 first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

U.S. health care costs a lot, and not just in money

Health spending in the United States is highest in the world, driven in part by administrative complexity. To date, studies examining the administrative costs of American health care have primarily focused on clinicians and organizations—rarely on patients.

A new study in Health Services Research finds administrative complexity in the U.S. health care system has consequences for access to care that are on par with those of financial barriers like copays and deductibles. In other words, we pay for health care in two ways: in money and in the hassle of dealing with a complex, confusing, and error-riddled system. Both are barriers to access. The study was led by Michael Anne Kyle, and I am a coauthor.

Main Findings

Nearly three-quarters (73%) of people surveyed reported doing at least one health care-related administrative task in the past 12 months. Such administrative tasks include: appointment scheduling; obtaining information from an insurer or provider; obtaining prior authorizations; resolving insurance or provider billing issues; and resolving premium problems.Administrative tasks often impose barriers to care: Nearly one-quarter (24.4%) of survey respondents reported delaying or foregoing needed care due to administrative tasks.This estimate of administrative barriers to access to care is similar to those of financial barriers to access: a 2019 Kaiser Family Foundation survey, found that 26% of insured adults 18-64 said that they or a family member had postponed or put off needed care in the past 12 months due to cost.Administrative burden has consequential implications for equity. The study finds administrative burden falls disproportionately on people with high medical needs (disability) and that existing racial and socioeconomic inequities are associated with greater administrative burden.Methods

To measure the size and consequences of patients’ administrative roles, we used data from the nationally representative March 2019 Health Reform Monitoring Survey of insured, nonelderly adults (18-64) to assess the annual prevalence of five common types of administrative tasks patients perform: (1) appointment scheduling; (2) obtaining information from an insurer or provider; (3) obtaining prior authorizations; (4) resolving insurance or provider billing issues; (5) and resolving insurance premium problems. The study examined the association of these tasks with two important measures of their burden: delayed and forgone care.

Conclusions

High administrative complexity is a central feature of the U.S. health care system. Largely overlooked, patients frequently do administrative work that can create burdens resulting in delayed or foregone care. The prevalence of delayed or foregone care due to administrative tasks is comparable to similar estimates of cost-related barriers to care. Administrative complexity is endemic to all post-industrial health systems, but there may be opportunity to design administrative tools with greater care to avoid exacerbating or reinforcing inequities.

The post U.S. health care costs a lot, and not just in money first appeared on The Incidental Economist.September 8, 2021

The next attack on the Affordable Care Act may cost you free preventive health care

Paul Shafer is an assistant professor of Health Law, Policy, and Management at the Boston University School of Public Health (@shaferpr). Alex Hoagland is a PhD Candidate in Health Economics at Boston University (@Hoagland_Alex).

Many Americans breathed a sigh of relief when the Supreme Court left the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in place following its third major legal challenge in June 2021. This decision left widely supported policies in place, like ensuring coverage regardless of preexisting conditions, coverage for dependents up to age 26 on their parents’ plan and removal of annual and lifetime benefit limits.

But the hits keep coming. One of the most popular benefits offered by the ACA, free preventive care through many employer-based and marketplace insurance plans, is under attack by another legal domino, Kelley v. Becerra. As University of Michigan law professor Nicholas Bagley sees it, “[t]his time, the law’s opponents stand a good chance of succeeding.”

We are public health and economics researchers at Boston University who have been studying how preventive care is covered by the ACA and what this means for patients. With this policy now in jeopardy, health care in the U.S. stands to take a big step backward.

What did the ACA do for preventive health?

The Affordable Care Act tried to achieve the twin ideals of making health care more accessible while reducing health care spending. It created marketplaces for individuals to purchase health insurance and expanded Medicaid to increase coverage for more low-income people.

One way it has tried to reach both goals is to prioritize preventive services that maximize patient health and minimize cost, like cancer screenings, vaccinations and access to contraception. Eliminating financial barriers to health screenings increases the likelihood that common but costly chronic conditions, such as heart disease, will be diagnosed early on.

Section 2713 of the ACA requires insurers to offer full coverage of preventive services that are endorsed by three federal groups: the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices and the Health Resources and Services Administration. This means that eligible preventive services ordered by your doctor won’t cost you anything out of pocket. For example, the CARES Act used this provision to ensure COVID-19 vaccines would be free for many Americans.

Removing the financial barrier has drastically reduced the average cost of a range of preventive services. Our study found that the costs of well-child visits and mammograms were reduced by 56% and 74%, respectively, from 2006 to 2018. We also found that the ACA reduced the share of children’s preventive checkups that included out-of-pocket costs from over 50% in 2010 to under 15% in 2018.

Residual costs for preventive services remain

Despite these reductions in costs, there are limitations to this benefit. For example, it doesn’t cover follow-up tests or treatments. This means that if a routine mammogram or colonoscopy reveals something that requires further care, patients may have to pay for the initial screening test, too. And some patients still receive unexpected bills for preventive care that should have been covered. This can happen, for example, when providers submit incorrect billing codes to insurers, which have specific and often idiosyncratic preventive care guidelines.

We also studied the residual out-of-pocket costs that privately insured Americans had after using eligible preventive services in 2018. We found that these patients paid between $75 million to $219 million per year combined for services that should have been free for them. Unexpected preventive care bills were most likely to hit patients living in rural areas or the South, as well as those seeking women’s services such as contraception and other reproductive health care. Among patients attempting to get a free wellness visit from their doctor, nearly 1 in 5 were later asked to pay for it.

Nevertheless, the preventive health provision of the ACA has resulted in significant reductions in patient costs for many essential and popular services. And removing financial barriers is a key way to encourage patients to use preventive services intended to protect their health.

The threat of Kelley v. Becerra

The plaintiffs who brought the latest legal challenge to the ACA, Kelley v. Becerra, object to covering contraception and preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV on religious and moral grounds. The case is currently awaiting decision in a district court in Texas, but seems to be headed to the Supreme Court.

The case rests on two legal issues: 1) violation of the nondelegation doctrine, and 2) the appointments clause of the Constitution. The nondelegation doctrine is a rarely used legal argument that requires Congress to specify how their powers should be used. It essentially argues that Congress was too vague by not specifying which preventive services would be included in Section 2713 up front. The appointments clause specifies that the people using government powers must be “officers of the United States.” In this case, it is unclear whether those in the federal groups that determine eligible preventive care services qualify.

Texas District Judge Reed O’Connor has indicated so far that he takes a kind view toward the plaintiff’s case. He could rule that this provision of the ACA is unconstitutional and put the case on a path to the Supreme Court.

Patients stand to lose more than just money

If Section 2713 were repealed, insurers would have the freedom to reimpose patient cost-sharing for preventive care. In the short run, this could increase the financial strain that patients face when seeking preventive care and discourage them from doing so. In the long run, this could result in increased rates of preventable and expensive-to-treat chronic conditions. And because Section 2713 is what allows free COVID-19 vaccines for those with private health insurance, some patients may have to pay for their vaccines and future boosters if the provision is axed.

The ACA has been instrumental in expanding access to preventive care for millions of Americans. While the ACA’s preventive health coverage provision isn’t perfect, a lot of progress that has been made toward lower-cost, higher-value care may be erased if Section 2713 is repealed.

Lower-income patients will stand to lose the most. And it could make ending the COVID-19 pandemic that much harder.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. Research for this piece was supported by Arnold Ventures.

The post The next attack on the Affordable Care Act may cost you free preventive health care first appeared on The Incidental Economist.The Time to Vaccinate the World is Now

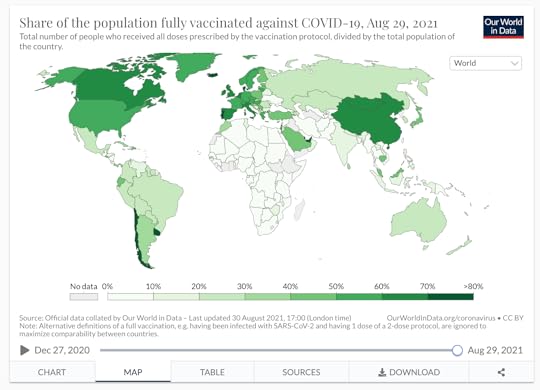

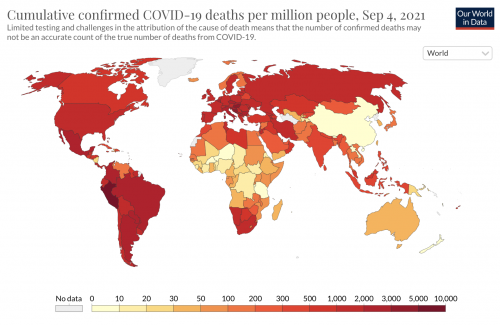

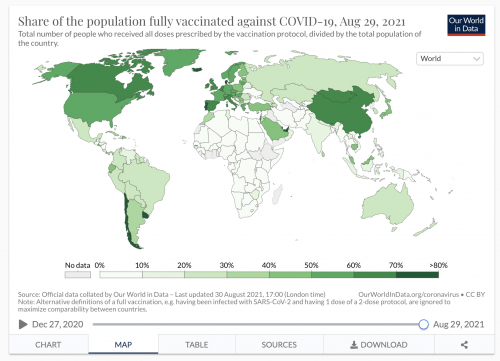

Much of the world is on fire with COVID-19, new variants continue to emerge, and places like Brazil, India, and the United States see repeated waves of infection.

Herd immunity is not working. We need to get the world vaccinated, and we need to do it now. Andy Slavitt and Jeremy Farrar have put forward a goal of vaccinating 70% of the world population with at least one dose by March 2022 (210 days) with a public launch at the UN General Assembly meeting in September (Inside the Bubble podcast, August 25, 2021). We’ll add a goal, that 80% of the world population is fully vaccinated by Summer 2022. This will be an enormous challenge, but it is achievable.

Why We Need to Vaccinate Now

We need to vaccinate the world because the pandemic continues to rage worldwide, killing millions, leaving many survivors debilitated and wreaking havoc on economies. Periodic waves of infection overwhelm health care systems, causing excess death and demoralizing clinical staff. Vaccines reduce the rate of spread, and they keep people out of hospitals.

We now have almost 40% of the world’s population vaccinated. This sounds better than it is. The proportion of the population that is vaccinated varies shockingly around the globe. We’re getting most people vaccinated in the US and Canada, Western Europe, and China. Some people are immunized in Russia and Central and South America. But few of the more than 3 billion people in most of Africa and South Asia are vaccinated, including < 1% of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Nigeria, Papua New Guinea, or Zambia.

We are 18 months into the pandemic, and already dozens of variants have emerged. Several are sweeping across the globe, driven by their ability to proliferate rapidly and to evade immunity. It’s only a matter of time before a variant with high-level vaccine escape emerges, and even vaccinated people start getting sick again in large numbers. The more virus is circulating, the more chances for variants to arise. We control new variants by preventing the spread of the virus, and vaccination is the best way to do that.

The COVAX Alliance has shipped 215 million doses of vaccine to date. That’s a start, but it’s nowhere close to meeting the need, and many countries, particularly in underdeveloped regions, have vaccination rates that are only in the single digits.

Can We Vaccinate the World?

Yes, we can. We have produced about 4 billion doses of vaccines in the past 9 months. To get everyone in the world two doses of vaccine will require another 12 billion doses. That’s a lot of vaccine, but we can do it. COVAX estimates global vaccine production capacity at 8 billion doses in 2021 and 42 billion doses in 2022. The bigger challenge is getting vaccines into people’s arms. That’s going to be a huge lift, and that’s why universal vaccination needs US leadership, UN and WHO support for international mobilization, and massive logistics support from many countries to get vaccinators trained and deployed, supplies procured and distributed, cold chains setup, regulatory approvals obtained, record-keeping established, and vaccines administered.

There is precedent for international medical mobilization to fight infectious disease. Under President George W. Bush, the US-led the PEPFAR initiative to deliver HIV medications worldwide. The success of this program saved millions of lives in Africa and remains an enduring legacy.

How the US Comes Out Ahead by Leading the Effort

David Cutler and Larry Summers estimated that COVID has cost the US $16 trillion. The economic impact globally dramatically exceeds this. Operation Warp Speed cost $12 billion to develop and deploy vaccines in the US. It has already more than paid for itself. Ramping up vaccine production to produce 12 billion doses might cost $25 billion, and the logistics and deployment might cost another $50 billion. That’s not trivial spending.

Consider, however, that the US will lose trillions of dollars of GDP each year as long as the pandemic continues. We risk seeing regional economic and potentially even political collapse in many parts of the world. Congress is considering multi-trillion-dollar infrastructure plans. Global mobilization for vaccination will quickly pay for itself in maintaining the economic viability of our trading partners. And, of course, saving humanity, that’s priceless.

Moreover, the larger the population of infected people on the planet, the more rapidly COVID variants emerge. The whole world is connected now, and COVID has shown that it rapidly crosses oceans. Fighting COVID in the world is essential to control it at home.

David J. States, MD PhD is the Chief Science/Medical Officer of Angstrom Bio, Austin, TX.

The post The Time to Vaccinate the World is Now first appeared on The Incidental Economist.September 7, 2021

Childhood Obesity and Problems With Research

Between 2017 and 2018, obesity affected about 14.4 million children and adolescents in the United States. In order to create treatments, interventions, and health policies to adequately address this issue, we need solid data from well-conducted studies. In today’s episode we discuss why we’re largely lacking such data, and how we can fix that.

The post Childhood Obesity and Problems With Research first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

Where are the social workers on network TV dramas?

For a cheap Friday date-night, Veronica and I binge-watched the TV drama Chicago Med. It’s a fun, albeit cheesy Dick Wolf hospital drama—part soap opera, part surprisingly serious and earnest depiction of our urban ills. The show’s physical layout is apparently based on Rush University Medical Center.

Sometimes intentionally, sometimes not, such pop-culture fare reveals important information about what American society values, our blindspots and where our culture is headed–at least within the target demographics served by these shows.

Plotlines include a 14-year-old girl married to a 50-something sleazy preacher, myriad gunshot wound patients, a homeless pregnant youth who was also a victim of child abuse, patients with complicated lives facing serious cancers and other life-threatening conditions, families that require respite services and help paying huge medical bills.

One thing these plotlines didn’t include: Social workers. Leaving aside an insulting and grossly-stereotyped depiction of a welfare department caseworker who didn’t know the name of his patient, there’s no social worker in sight.

The social work craft is invisible on Chicago Med. It’s invisible on most television shows and most of our popular culture. When social workers are shown, they’re often depicted in cardboard ways: As naïve secular saints. Or as overworked, well-meaning, but incompetent bunglers. Or as malevolent bureaucrats who take children away.

(Friends on Twitter identified some notable exceptions, including the series Judging Amy, and the lovely little film Short Term 12.) That’s a terrible blindspot in our cultural understanding of medical and social care.

Within the real-life Rush University Medical Center, social workers would have been all over each of these plotlines. They’d actually be doing many tasks ostensibly performed by the main characters: Working with patients and families on end-of-life care, coordinating with social services, navigating paperwork snarls to obtain wheelchairs and other durable medical equipment, performing behavioral health assessments, and more.

The COVID pandemic shines a spotlight on the skill, dedication, and commitment of doctors, nurses, and the front-line public health workforce. That’s fantastic.

Less widely noted is the fact that many of these front-line workers are actually social workers and allied professionals.

Who do you think are out there trying to secure housing and food for COVID patients so they can physically distance from loved-ones and others?Who do you think leads and manages homeless shelters, food pantries, and other social services?Who do you think serves individuals at-risk of behavioral crisis who might otherwise have violent encounters with first-responders?Then there are the outreach staff and nonprofit managers serving people who live with serious mental illness and substance use disorders, and others who assist individuals and families on matters of serious physical, mental, and developmental disabilities.I myself am a public health researcher. I’m not a social worker, but I’ve spent the last eighteen years at the University of Chicago’s Crown School of Social Work, Policy, and Practice. I strongly identify with my colleagues in the social work profession.

So many of my amazing students, practitioner partners, and research colleagues are social workers—at the University of Chicago, in partner organizations such as Youth Guidance, NAMI, Thresholds, Chicago Department of Public Health, Chicago Public Schools, and in other organizations.

My wife Veronica is a nurse-social worker. She’s a care coordinator at Lurie Children’s Hospital. Her patients face medical challenges from cancer to intellectual disabilities and eating disorders, alongside psychosocial challenges tranging from poverty and family dislocation, the need to coordinate complex educational and medical services, the need to secure durable medical equipment, the need to deal with Medicaid and other public assistance programs.

It’s a tough gig. The work of course requires altruism and dedication to patients. It requires more, too: Detailed knowledge of medical and social service systems, a thick Rolodex of bureaucratic contacts to get things done, cultural competence, resourcefulness, training, and grit.

COVID continues to be a brutal trial for so many social workers across the board. I’m proud of so many colleagues and friends, who have risen to this challenge. I feel for them and for many others who see so much, been through so much, endure constant issues of burnout and related challenges.

We in public health and in health care, loudly proclaim that American society must address the social determinants of health. yet we routinely overlook or denigrate social workers and allied professionals whose primary mission and training is precisely to address these determinants.

We must do better.

The post Where are the social workers on network TV dramas? first appeared on The Incidental Economist.Recent publications from Boston University’s Department of Health Law, Policy and Management: September 2021 Edition

Below are recent publications from Boston University’s Department of Health Law, Policy and Management. You can find all posts in this series here.

September 2021 Edition

Austad K, Juarez M, Shryer H, Hibberd PL, Drainoni ML, Rohloff P, Chary A. Improving the experience of facility-based delivery for vulnerable women through obstetric care navigation: a qualitative evaluation. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021 Jun 11; 21(1):425. PMID: 34116648.

Bindman AB, Frakt A, Tachibana C. From the Editors’ Desk. Health Serv Res. 2021 Jun; 56(3):345. PMID: 34029394.

Brady KJS, Sheldrick RC, Ni P, Trockel MT, Shanafelt TD, Rowe SG, Kazis LE. Examining the measurement equivalence of the Maslach Burnout Inventory across age, gender, and specialty groups in US physicians. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2021 Jun 05; 5(1):43. PMID: 34089412. Online ahead of print.

Carey K, Luo Q, Dor A. Quality and Cost in Community Health Centers. Med Care. 2021 Jun 03. PMID: 34081675.

Garvin LA, Pugatch M, Gurewich D, Pendergast JN, Miller CJ. Interorganizational Care Coordination of Rural Veterans by Veterans Affairs and Community Care Programs: A Systematic Review. Med Care. 2021 06 01; 59(Suppl 3):S259-S269. PMID: 33976075.

Gordon SH, Beilstein-Wedel E, Rosen AK, Zheng T, Kelley AT, Cook J, Zahakos SS, Wagner TH, Vanneman ME. County-level Predictors of Growth in Community-based Primary Care Use Among Veterans. Med Care. 2021 Jun 01; 59(Suppl 3):S301-S306. PMID: 33976080.

Harris MTH, Bagley SM, Maschke A, Schoenberger SF, Sampath S, Walley AY, Gunn CM. Competing risks of women and men who use fentanyl: “The number one thing I worry about would be my safety and number two would be overdose“. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2021 06; 125:108313. PMID: 34016300.

Hayaki J, Conti MT, Bailey GL, Herman DS, Anderson BJ, Stein MD. Negative affect-associated drug refusal self-efficacy, illicit opioid use, and medication use following short-term inpatient opioid withdrawal management. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2021 Jul; 126:108309. PMID: 34116827.

Hoagland A, Shafer P. Out-of-pocket costs for preventive care persist almost a decade after the Affordable Care Act. Prev Med. 2021 Jun 16; 150:106690. PMID: 34144061. Online ahead of print.

Jernigan DH. Cannabis chains of influence from a US perspective. Addiction. 2021 Jun 09. PMID: 34105204.

Knudsen HK, Drainoni ML, Gilbert L, Huerta TR, Oser CB, Aldrich AM, Campbell ANC, Crable EL, Garner BR, Glasgow LM, Goddard-Eckrich D, Marks KR, McAlearney AS, Oga EA, Scalise AL, Walker DM. Corrigendum to “Model and approach for assessing implementation context and fidelity in the HEALing Communities Study” [Drug Alcohol Depend. 217 (2020) 108330]. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021 Jul 01; 224:108742. PMID: 33984669.

Mattocks KM, Kroll-Desrosiers A, Kinney R, Elwy AR, Cunningham KJ, Mengeling MA. Understanding VA’s Use of and Relationships With Community Care Providers Under the MISSION Act. Med Care. 2021 Jun 01; 59(Suppl 3):S252-S258. PMID: 33976074.

Meshesha LZ, Emery NN, Blevins CE, Battle CL, Sillice MA, Marsh E, Feltus S, Stein MD, Abrantes AM. Behavioral activation, affect, and self-efficacy in the context of alcohol treatment for women with elevated depressive symptoms. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2021 Jun 10. PMID: 34110890.

Mills JM, Morgan JR, Dhaliwal A, Perkins RB. Eligibility for cervical cancer screening exit: Comparison of a national and safety net cohort. Gynecol Oncol. 2021 Jun 03. PMID: 34090706. Online ahead of print.

Mulcahey MJ, Thielen CC, Slavin MD, Ni P, Jette AM. Pediatric measure of participation short forms version 2.0: development and evaluation. Spinal Cord. 2021 Jun 02. PMID: 34079073. Online ahead of print.

Neufeld MY, Kimball S, Stein AB, Crosby SS. Correction to: Forensic evaluation of alleged wrist restraint/handcuff injuries in survivors of torture utilizing the Istanbul Protocol. Int J Legal Med. 2021 Jun 09. PMID: 34106336.

Prentice JC, Mohr DC, Zhang L, Li D, Legler A, Nelson RE, Conlin PR. Increased Hemoglobin A1c Time in Range Reduces Adverse Health Outcomes in Older Adults With Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2021 Jun 14. PMID: 34127496. Online ahead of print.

Vax S, Farkas M, Russinova Z, Mueser KT, Drainoni ML. Enhancing organizational readiness for implementation: constructing a typology of readiness-development strategies using a modified Delphi process. Implement Sci. 2021 Jun 10; 16(1):61. PMID: 34112191.

Vimalananda VG, Wormwood JB, Qian S, Meterko M, Sitter KE, Fincke BG. The Effect of Clinicians’ Personal Acquaintance on Specialty Care Coordination as the Sharing of an EHR Increases. J Ambul Care Manage. 2021 Jul-Sep 01; 44(3):227-236. PMID: 34016849.

The post Recent publications from Boston University’s Department of Health Law, Policy and Management: September 2021 Edition first appeared on The Incidental Economist.September 3, 2021

The largest risk-group we must reach to reduce COVID vaccination disparities

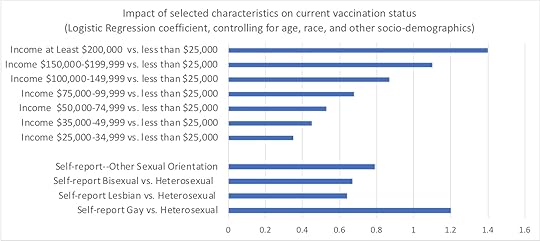

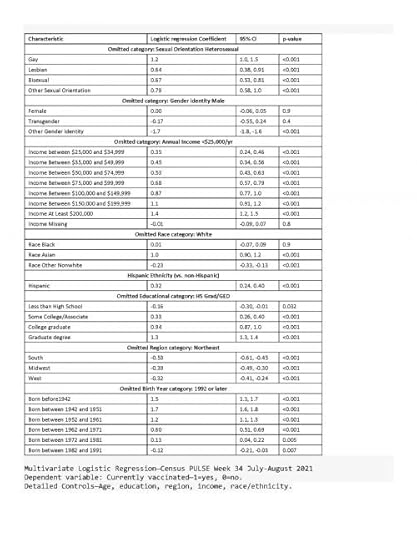

Last night I downloaded the latest Census Bureau July-August week 34 PULSE data. Over two cups of coffee, I ran the obvious multivariable logistic regressions to examine who is now fully vaccinated against COVID. See the bottom of this post for the full set of resulting Logit coefficients.

I’m sure Reviewer 2 would order due refinements to my quick analysis, were it immediately submitted for peer-review publication. My capacious study limitations section would note the inherent challenges of population surveys to gauge contentious questions like this. These data surely include response biases and likely overstate the true prevalence of COVID vaccination.

The overall patterns and disparities remain clear enough. Of course, we see huge disparities across regions, by education and by income. A bit more surprising: One group appears especially vulnerable and requires specific outreach…

Yup. We must formulate culturally competent public health messaging for heterosexual non-Hispanic white Americans. This group conspicuously lags in vaccination status.Among self-identified male respondents, heterosexual men were almost four times as likely to report not to be fully vaccinated (19%) as were gay men (5%)–an absolute different quite similar to the gradient observed between men with incomes less than $25,000 and those with incomes between $75,000 and $100,000.I know that there daunting obstacles to reaching this disparity-population of heterosexual American men. We can’t let these barriers deter us. I’m joking–sort of. OK not really.Political and social polarization are serious obstacles to our COVID efforts. Tribalization of public health may ironically increase vaccination rates among sexual and gender minorities, the educated, residents of blue states, and the socially liberal. We must find ways to push past these divides. Recent vaccination promotion efforts by Senator McConnell and other Republicans are extremely valuable. That is a positive development. Public health is too important to be polarized on partisan or cultural lines.(Full unweighted logistic regression results shown below….)

Recent vaccination promotion efforts by Senator McConnell and other Republicans are extremely valuable. That is a positive development. Public health is too important to be polarized on partisan or cultural lines.(Full unweighted logistic regression results shown below….)

The post The largest risk-group we must reach to reduce COVID vaccination disparities first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

The post The largest risk-group we must reach to reduce COVID vaccination disparities first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

September 2, 2021

Mergers aren’t great; why do they keep getting approved?

Elsa Pearson is a senior policy analyst at Boston University School of Public Health. She tweets at @epearsonbusph.

Health care mergers and acquisitions can have significant negative consequences on patients, providers, and communities. Yet, questionable deals keep getting approved. Inspired (read as: frustrated) by the pending merger in Rhode Island between Lifespan and Care New England, I dove into the antitrust machinery in place to stop these mega deals.

It’s clear that mechanisms already exist to curb potentially harmful mergers and promote industry competition. It’s also clear they aren’t being used to the fullest extent. Unless these checks and balances lead to mergers being denied, their power over the market is limited.

Experts have been raising the alarm on health care consolidation for a while. The research shows mergers rarely lead to better care quality, access, or prices. Proposed mergers must be assessed and approved based on evidence, not industry pressure. If nothing changes, the consequences will be felt for years to come.

Read the full piece in at STAT!

Research for this article was supported by Arnold Ventures.

The post Mergers aren’t great; why do they keep getting approved? first appeared on The Incidental Economist.September 1, 2021

Rx vs. OTC (Part Two): Costs and Benefits

Izabela Sadej, MSW, is a policy analyst at Boston University School of Public Health. She tweets at @IzzySadej. Research for this article was supported by Arnold Ventures.

This post is the second in a series that examines pharmaceutical drug distribution in the United States. The first post described the FDA drug classification process [prescription or over-the-counter (OTC)] and how drugs can switch classifications, while this piece focuses on the costs and benefits associated with both. The next and final post will explore alternative approaches to drug distribution, with a particular focus on the role of pharmacists.

Prescription Drugs

The primary purpose for prescription drug requirements is concern for patient safety and well-being. Prescription requirements allow health care professionals to provide education, oversight, and care management when patients need pharmaceutical care, especially for drugs that can be particularly harmful if not properly managed. A person’s medical history and current health status are considered before prescriptions are filled, allowing for appropriate course of treatment and dosage.

Consumers cannot always accurately self-diagnose and self-medicate when purchasing their own medicine, which highlights the importance of access to health care professionals when pharmaceutical drugs are involved. Concerns for drug misuse and abuse are valid; even with access hurdles, prescription drugs are among the most misused and abused substances.

However, while prescription drugs are essential to millions of people, particularly those who suffer from chronic illness, they have become increasingly expensive. A 2021 report found that three in ten adults did not take their prescriptions due to costs. Consumer drug expenditure heavily depends on health insurance coverage, if one has insurance at all, and can fluctuate depending on branding.

OTC Drugs

OTC classification allows for easier, universal access to important medicines. It is estimated that OTC drugs are used by 81 percent of adults as a first response to minor ailments and have provided symptomatic relief to 60 million people who probably wouldn’t otherwise seek medical treatment.

Barriers – such as cost, lack of insurance, stigma, etc. – limit under-served communities from accessing pharmaceutical care directly from a doctor. The CDC found that 30.4 million people were uninsured in the beginning of 2020 and nearly half of adults reported that they or someone in their household deferred medical care due to COVID-19. OTC approval has the potential to alleviate some of this burden.

For example, OTC approval could increase access to Naloxone, a largely unavailable medicine that rapidly reverses an opioid overdose. While several states have created laws that allow pharmacists to distribute the drug without a prescription, access barriers continue to exist that have resulted in advocacy to approve Naloxone for OTC use. Some of these barriers include negative stigma about carrying Naloxone, health care provider discomfort in distributing Naloxone, its high cost, and the prevalence of medicine and pharmacy deserts. OTC distribution won’t address all of these, but could address some. In addition, structural racism disproportionately increases the risk of overdose and death in communities of color, causing opioid-related overdoses to continue to rise. Greater access to Naloxone could also address this issue.

OTC drug availability also promotes patient autonomy and comfort when needing certain medicines. For instance, when the Plan B One-Step medication became available OTC, it allowed individuals to access emergency contraception in a timely and discreet manner. Confidentiality is an important consideration for medication access, particularly for women’s health and pregnancy-related care.

Although consumers normally pay out-of-pocket for OTC drugs, which can be a barrier to their use, prescription to OTC drug switches have been found to save both time and costs. This benefits consumers, providers, and insurers alike by limiting unnecessary clinic visits and reducing overall drug prices.

The classification system of prescription and OTC drugs creates both opportunities and barriers for several stakeholders, but especially consumers. It is important to remember that the end goal should always be providing people with access to the medicines they need.

The post Rx vs. OTC (Part Two): Costs and Benefits first appeared on The Incidental Economist.Aaron E. Carroll's Blog

- Aaron E. Carroll's profile

- 42 followers