Aaron E. Carroll's Blog, page 115

January 2, 2018

What We Mean When We Say Evidence-Based Medicine

The following originally appeared on The Upshot (copyright 2017, The New York Times Company).

In medicine, the term “evidence-based” causes more arguments than you might expect.

And that’s quite apart from the recent political controversy over why certain words were avoided in Centers for Disease Control and Prevention budget documents.

The arguments don’t divide along predictable partisan lines, either.

The mission of “evidence-based medicine” is surprisingly recent. Before its arrival, much of medicine was based on clinical experience. Doctors tried to figure out what worked by trial and error, and they passed their knowledge along to those who trained under them.

Many were first introduced to evidence-based medicine through David Sackett’s handbook, first published in 1997. The book taught me how to use test characteristics, like sensitivity and specificity, to interpret medical tests. It taught me how to understand absolute risk versus relative risk. It taught me the proper ways to use statistics in diagnosis and treatment, and in weighing benefits and harms.

It also firmly established in my mind the importance of randomized controlled trials, and the great potential for meta-analyses, which group individual trials for greater impact. This influence is apparent in what I write for The Upshot.

But evidence-based medicine is often described quite differently.

Many of its supporters say that using evidence-based medicine can address the problems of cost, quality and access that bedevil the health care system. If we all agree upon best practices — based on data and research — we can reduce unnecessary care, save money and push people into pathways to yield better results.

Critics of evidence-based medicine, many of them from within the practice of medicine, point to weak evidence behind many guidelines. Some believe that medicine is more of an “art” than a “science” and that limiting the practice to a cookbook approach removes focus from the individual patient.

Some of these critics (as well as many readers who comment on my articles) worry that guidelines line the pockets of pharmaceutical companies and radiologists by demanding more drugs and more scans. Others worry that evidence-based medicine makes it harder to get insurance companies to pay for needed care. Insurance companies worry that evidence-based recommendations put them on the hook for treatment with minimal proven value.

Everyone is a bit right here, and everyone is a bit wrong. This battle isn’t new; it has been going on for some time. It’s the old guard versus the new. It’s the patient versus the system. It’s freedom versus rationing. It’s even the individual physician versus the proclamations of a specialized elite.

Because of the tensions in that last conflict, this debate has become somewhat political.

The benefits of evidence-based medicine, when properly applied, are obvious. We can use test characteristics and results to make better diagnoses. We can use evidence from treatments to help people make better choices once diagnoses are made. We can devise research to give us the information we are lacking to improve lives. And, when we have enough studies available, we can look at them together to make widespread recommendations with more confidence than we’d otherwise be able.

When evidence-based medicine is not properly applied, though, it not only undermines its reasons for existence, but it also can lead to harm. Guidelines — and there are many — are often promoted as “evidence-based” even though they rely on “evidence” unsuited to its application. Sometimes, these guidelines are used by vested interests to advance an agenda or control providers.

Further, too often we treat all evidence as equivalent. I’ve lost track of the number of times I’ve been told that “research” proves I’m wrong. All research is not the same. A hierarchy of quality exists, and we have to be sure not to overreach.

There is a difference between statistical significance and clinical significance. Get a large enough cohort together, and you will achieve the former. That by itself does not ensure that the result achieves clinical significance and should alter clinical practice.

Finally, we have to recognize that even when good studies are done, with clinically significant results, we shouldn’t over-extrapolate the findings. Just because something worked in a particular population doesn’t mean we should do the same things to another group and say that we have evidence for it.

Years ago, Trisha Greenhalgh and colleagues wrote an article in the BMJ citing evidence-based medicine as “a movement in crisis.” It argued that we’ve moved too much from focusing on disease to risk. This point, more than any other, highlights the problem evidence-based medicine seems to have in the public sphere.

Too many articles, studies and announcements are quick to point out that something or other has been proved to be dangerous to our health, without a good explanation of the magnitude of that risk, or what we might reasonably do about it.

Big data, gene sequencing, artificial intelligence — all of these may provide us with lots of information on how we might be at risk for various diseases. What we lack is knowledge about what to do with what we might learn.

If evidenced-based medicine is to live up to its potential, it seems the focus should be on that side of the equation as well, instead of taking best guesses and calling them evidence-based. This, probably more than anything else, has made the term so widely mistrusted.

December 28, 2017

The Leap to Single-Payer: What Taiwan Can Teach

The following originally appeared on The Upshot (copyright 2017, The New York Times Company). It is jointly authored by Aaron Carroll and Austin Frakt.

Taiwan is proof that a country can make a swift and huge change to its health care system, even in the modern day.

The United States, in part because of political stalemate, in part because it has been hemmed in by its history, has been unable to be as bold.

Singapore, which we wrote about in October, tinkers with its health care system all the time. Taiwan, in contrast, revamped its top to bottom.

Less than 25 years ago, Taiwan had a patchwork system that included insurance provided for those who worked privately or for the government, or for trade associations involving farmers or fishermen. Out-of-pocket payments were high, and physicians practiced independently. In March 1995, all that changed.

After talking to experts from all over the world, Taiwan chose William Hsiao, a professor of economics at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, to lead a task force to design a new system. Uwe Reinhardt, a longtime Princeton professor, also contributed significantly to the effort. (Mr. Reinhardt, who died last month, was a panelist on an Upshot article comparing international health systems in a tournament format.) The task force studied countries like the United States, Britain, France, Canada, Germany and Japan.

In the end, Taiwan chose to adopt a single-payer system like that found in Medicare or in Canada, not a government-run system like Britain’s. At first, things did not go as well as hoped. Although the country had been planning the change for years, it occurred quite quickly after democracy was established in the early 1990s. The system, including providers and hospitals, was caught somewhat off guard, and many felt that they had not been adequately prepared. The public, however, was much happier about the change.

Today, most hospitals in Taiwan remain privately owned, mostly nonprofit. Most physicians are still either salaried or self-employed in practices.

The health insurance Taiwan provides is comprehensive. Both inpatient and outpatient care are covered, as well as dental care, over-the-counter drugs and traditional Chinese medicine. It’s much more thorough than Medicare is in the United States.

Access is also quite impressive. Patients can choose from pretty much any provider or therapy. Wait times are short, and patients can go straight to specialty care without a referral.

Premiums are paid for by the government, employers and employees. The share paid by each depends on income, with the poor paying a much smaller percentage than the wealthy.

Taiwan’s cost of health care rose faster than inflation, as it has in other countries. In 2001, co-payments for care were increased, and in 2002, they went up again, along with premiums. In those years, the government also began to reduce reimbursement to providers after a “reasonable” number of patients was seen. It also began to pay less for drugs. Finally, it began to institute global budgets — caps on the total amount paid for all care — in the hope of squeezing providers into becoming more efficient.

Relative to the United States and some other countries, Taiwan devotes less of its economy to health care. In the early 2000s, it was spending 5.4 percent of G.D.P., and by 2014 that number had risen to 6.2 percent. By comparison, countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development spend on average more than 9 percent of G.D.P. on health care, and the United States spends about twice that.

After the most recent premium increase in 2010 (only the second in Taiwan’s history), the system began to run surpluses.

This is not to say the system is perfect. Taiwan has a growing physician shortage, and physicians complain about being paid too little to work too hard (although doctors in nearly every system complain about that). Taiwan has an aging population and a low birthrate, which will push the total costs of care upward with a smaller base from which to collect tax revenue.

Taiwan has done a great job at treating many communicable diseases, but more chronic conditions are on the rise. These include cancer and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease, all of which are expensive to treat.

The health system’s quality could also be better. Although O.E.C.D. data aren’t available for the usual comparisons, Taiwan’s internal data show that it has a lot of room for improvement, especially relating to cancer and many aspects of primary care. Taiwan could, perhaps, fix some of this by spending more.

As we showed in our battle of the health care systems, though, complaints can be made about every system, and the one in the United States is certainly no exception. For a country that spends relatively little on health care, Taiwan is accomplishing quite a lot.

Comparing Taiwan and the United States may appear to be like comparing apples and aardvarks. One is geographically small, with only 23 million citizens, while the other is vast and home to well above 300 million. But Taiwan is larger than most states, and a number of states — including Vermont, Colorado and California — have made pushes for single-payer systems in the last few years. These have not succeeded, however, perhaps because there is less tolerance for disruption in the United States than the Taiwanese were willing to accept.

Regardless of which health system you might prefer, Taiwan’s ambition showed what’s possible. It took five years of planning and two years of legislative efforts to accomplish its transformation. That’s less time than the United States has spent fighting over the Affordable Care Act, with much less to show for it.

December 26, 2017

US life expectancy declined again. How much does that matter?

US life expectancy at birth declined for the second year in a row, by an estimated -0.1 years (-0.2 years for males, no change for females). When you use a small number to describe an event, it suggests that the consequences of the event are negligible. This is an illusion: the drop in life expectancy is a catastrophe. I’ll show this by translating that decrease into numbers that appropriately convey the magnitude of harm.

Let’s work through a series of questions about the CDC report.

First, what is life expectancy? Life expectancy at birth is the number of years that a newborn should expect to live, assuming age-specific mortality rates remain at their current levels. There’s a lot packed into this definition.

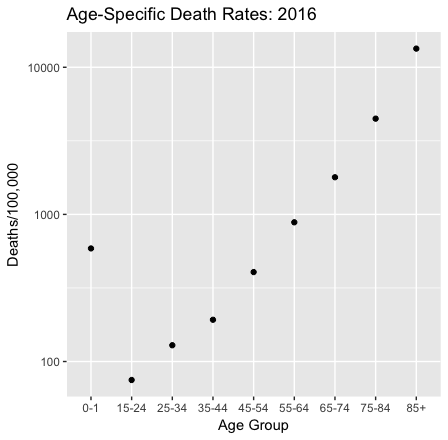

Age-specific death rates determine life expectancy. So if life expectancy changes it is because death rates changed. Death rates vary by age group: they are moderately high for infants, drop during childhood, and then rise as we age.

Data are from the CDC. Notice that the vertical axis is logarithmic. The age-specific death rate for children aged 2-14 years is missing from the CDC report.

Some calamities raise death rates across the lifespan, such as the flu epidemic at the end of the first world war. But if we compare 2015 and 2016 death rates, that isn’t what happened.

The change in death rates by age group from 2015 to 2016, as a percentage of 2015 rates. Data are from the CDC.

The blue bars show that for infants and the elderly, death rates fell. In fact, life expectancy improved for those 65 and older. But for everyone else death rates rose, and for young adults, they rose a lot. Moreover, the changes in age-specific death rates varied by race, gender, and (the CDC report doesn’t discuss this, but it’s true) the region of the US. The net effect of the changes in age-specific death rates across the lifespan and the population was a -0.1-year change in life expectancy at birth.*

Does a small decline in life expectancy matter? The change of -0.1 years/life is a -0.13% decline from the 2015 US life expectancy at birth (78.7 years). This is how your individual life prospects changed if you are an infant who happened to be born in 2016 instead of 2015. And, yes, those prospects only diminished a little.

But that’s not the only way to look at this: We should also look at the cumulative loss of life across the population.** Consider that for one birth cohort,

-0.1 years/infant × 4 million annual births = -400,000 years/cohort.

How large was that loss? There were 4,424 US deaths in the Iraq war. These men and women were on average about 26 years old at the times of their death. Life expectancy at 25 is 55 years, so let’s say that that’s how much life they lost, on average. Hence

4,424 deaths in Iraq × -55 years/death ≈ -243,000 years lost in Iraq.

Therefore the expected years of life lost for a single birth cohort due to the changes in death rates from 2015 to 2016 was larger than the years of life lost by Americans in the Iraq war.

The traditional monetary value of a year of life in cost-benefit analyses is $50,000, but a more reasonable contemporary value might be $100,000. If so, then the value of a -0.1-year change is

-400,000 years/cohort × $100,000/year = -$4 trillion/cohort.

How big is that? Well, the value of goods and services produced annually in the US is $19 trillion. The total value of US real estate is about $30 trillion. So the monetary value of a small change in life expectancy for a single cohort was within one order of magnitude of astronomically valuable things such as the stock of US real estate or annual US GDP.

What happened to raise the death rates of Americans aged 15-64? I don’t have a breakdown of the causes of death by age in 2016, but for the population as a whole, suicides rose 2%, unintentional accidents increased 10%, and drug overdose deaths rose by a stunning 21% from 2015 to 2016. These causes contribute significantly to overall mortality for people in this age group, and they likely played a role in the increased death rates. These causes of death are all to some degree preventable, but what are we doing about them? I cannot help but note that although the President has declared an opioid emergency there has been no visible public health action on this issue.

Why is this loss of life difficult to see? First, it’s hard to see because the individual deaths are scattered across the country, and they aren’t connected by a single cause.

Second, policymakers and commentators focus excessively on economic indicators when they measure national well-being. The monthly Bureau of Labor Statistics jobs report is a news event in a way that a release of CDC mortality data is not. These economic data matter, but they are not a proxy for national well-being. US employment rose in 2016, and so did the Gross Domestic Product. Nevertheless, death rates rose sharply for working-age Americans.

So how should we assess national well-being? The French government’s Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress (led by Joseph Stiglitz, Amartya Sen, and Jean-Paul Fitoussi) argued that

our [national] measurement system [should] shift emphasis from measuring economic production to measuring people’s well-being.

Measurements of well-being should include measures of population health, although we need to work through the conceptual challenges of such measures. The UN’s Human Development Indices (HDIs) do not work for me because they take years of schooling completed by students as a proxy for what they know. But the HDIs at least include life expectancy, and that’s a start.

*Keep in mind that the definition of life expectancy assumes that age-specific mortality rates will remain the same. That implies that when babies born in 2016 turn 34 in 2050, their age-specific death rate will be 129/100,000, the same as in 2016. However, death rates change from year to year (as we have just seen), so it’s unlikely that the age-specific death rates will stay constant as the 2016 birth cohort ages. Therefore, life-expectancy at birth is an uncertain predictor of how long an infant born today will live, although we do not have a better one. However, it is a good summary measure of the current force of mortality across the lifespan.

**Taking the population instead of the individual view of mortality is precisely John Donne’s point in his Meditation XVII (1624):

No man is an island entire of itself; every man

is a piece of the continent, a part of the main;

if a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe

is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as

well as any manner of thy friends or of thine

own were; any man’s death diminishes me,

because I am involved in mankind.

And therefore never send to know for whom

the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.

December 22, 2017

Healthcare Triage Podcast!

I haven’t been good about posting this, but Healthcare Triage has a podcast. Well, we’ve had one for some time, but it used to be just the audio of the live show. But now it’s a real podcast, released about every other week. I do some news, we have a guest, and then we answer your questions together! You can find the podcast in all the usual places, like iTunes, Soundcloud, or even on YouTube.

The four episodes so far are:

#1 Let’s Do This Thing – Guest: Dr. Lindsey Doe

#3 We’re All Going to Die – Guest: Dr. Tim Broach, MD

#4 What’s a Nurse Practitioner? – Guest: Aimee Carroll

I will be better about posting these in the future. By the way, to submit your questions to get answered in future episodes, go here!

December 21, 2017

Vacating an EEOC rule on wellness programs

A few months back, I flagged an opinion from a D.C. district court holding that a new EEOC rule governing wellness programs was arbitrary and capricious. The rule allowed employers to impose huge penalties on employees who refused to participate in wellness programs, even though the Americans with Disabilities Act says those programs must be “voluntary.”

In the court’s view, the EEOC had basically ignored the problem in its rulemaking, asserting without explanation that wellness programs backed by enormous penalties were somehow voluntary. I applauded the decision: I’ve been railing against the EEOC for two years now for blessing mandatory wellness programs over the ADA’s express prohibition.

But I was “a little flummoxed by the remedy.” The court declined to vacate the rule, instead leaving it intact while EEOC went back to the drawing board. I didn’t think the remand-without-vacatur remedy was appropriate given the depth of the rule’s deficiencies, the likelihood that EEOC would dither, and the very real prospect that no rule could pass legal muster. I thus “strongly encourage[d] the AARP to file a motion to amend the judgment” to ask the court to vacate the rule, but to stay its mandate—to put that judgment on hold—until January 2018.

To my delight, the AARP did exactly that. Better still, the district court yesterday granted AARP’s motion to amend the judgment. The court thought, with some reason, that vacating the rule in two weeks might be disruptive. But “there is plenty of time for employers to develop their 2019 wellness plans with knowledge that the [rule has] been vacated.” Plus, the court reasoned, “[i]t is far from clear that EEOC will view a 30% incentive level as sufficiently voluntary upon reexamination of the evidence presented to it.”

Beyond that, the court was concerned about the slow timeframe that EEOC proposed for devising a replacement rule. “If left to its own devices, … EEOC will not have a new rule ready to take effect for over three years—not what the Court envisioned when it assumed that the Commission could address its errors ‘in a timely manner.’”

The court therefore stayed its mandate through 2018, but held that the rule will be vacated as of January 1, 2019. That’s an enormous victory for those of us with deep misgivings about wellness programs.

I’m also gratified to see a district court give serious consideration to a remedial question after ruling on the merits. I endorsed this sort of bifurcated approach in my article, Remedial Restraint in Administrative Law. For any number of reasons, it’s rare that remedial questions get the attention they deserve when the parties are fighting over the legality of an agency action. Once that question has been resolved, it makes a ton of sense to allow the parties to circle back to the court with arguments about the remedy.

December 20, 2017

Healthcare Triage News: A Close Look at the Poorly Crafted Birth Control Rule

A couple of months ago, the Trump administration’s Department of Health and Human Services created an exemption to the Affordable Care Act’s requirement that employers cover birth control for their employees. Last week, a US District Court Judge said the rule couldn’t go into effect.

Special thanks to friend-of-the-show Nick Bagley for helping us understand all this stuff. You can find Nick’s original post here if you want more details.

Why New Blood Pressure Guidelines Could Lead to Harm

The following originally appeared on The Upshot (copyright 2017, The New York Times Company).

In the week before Thanksgiving, the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology released new guidelines for the diagnosis and management of high blood pressure. This, probably more than anything else, made my blood pressure go up over the holiday.

The problem was not the guideline itself but some of the news coverage it prompted, with pronouncements that millions more Americans would need to lower blood pressure or that nearly half of Americans now had high blood pressure. A lot of the coverage made it sound as if something drastic had happened overnight.

Nothing had. We just changed the definition of hypertension.

High blood pressure, in general, is not something we should ignore. It’s a major risk factor for heart disease, second perhaps only to smoking, and people with hypertension often need to make changes to reduce their risk of a heart attack or stroke. But, as is so often the case with medical news, matters are more complicated than the headlines or TV summaries.

The new data that led to this guideline revision came from the Sprint study, a large randomized controlled trial of blood pressure management that was published in The New England Journal of Medicine in 2015. More than 9,300 patients were put into one of two groups.

The first received standard care, which involved trying to keep systolic blood pressure (the higher of the two blood pressure measures) under 140. The second group got more intensive care, which meant trying to keep systolic blood pressure below 120. Achieving the latter, of course, required more therapy, mostly pharmacologic in nature.

The results were significant, with fewer patients in the intensive therapy group having an acute cardiovascular event or death. The evidence was so compelling that the trial was stopped early, so the results could be announced sooner rather than later. This decision itself brought a fair amount of media attention to its findings. The fact that those in the intensive therapy group also had more adverse events, like hypotension, syncope and acute kidney injury, got less attention.

Regardless, this is a significant trial, and we should treat it seriously. To generalize its results, however, we have to pay attention to the details of its methods. To be eligible for this study, in addition to having a systolic blood pressure from 130 to 180, patients had to be at particularly high risk of disease. They had to be at least 50 years old. They had to have one of the following health problems: another subclinical cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease or a Framingham 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease of 15 percent or more. Or they had to be 75 years or older.

They also had to have their blood pressure confirmed in three separate readingsin which patients were left alone in a room for five minutes. This is important, because patients often have elevated blood pressure just from being nervous when it’s being measured in the office. There’s even a name for it: white coat hypertension.

Because of white coat hypertension, guidelines for checking blood pressure in both children and adults recommend that after multiple readings in the office, worrisome findings should be confirmed by 24-hour measurement outside the office. This happens far too rarely. Instead, people get their blood pressure measured quickly in the office, are labeled hypertensive, and are then put on treatment pathways.

The Sprint study essentially showed that people truly at high risk should have their blood pressure managed more aggressively than we thought. But that has not been the message of news on the new guidelines. That has focused far more often on the many newly reclassified people with mild blood pressure, who were not the focus of the Sprint intervention.

In fact, almost none of the newly labeled hypertensive people (those with systolic blood pressure between 130 and 140) should be placed on medications. These people should be advised to eat right, exercise, drink responsibly, and not smoke.

That’s exactly what physicians would have been advising people before these changes. Is there anyone left who doesn’t know those things are important for good health?

So why alter the guideline at all? The conclusion of an accompanying articleargues that the guideline “has the potential to increase hypertension awareness, encourage lifestyle modification and focus antihypertensive medication initiation and intensification on U.S. adults with high” cardiovascular disease risk. In other words, much of the goal is to make news and potentially scare people into changing their behavior.

Unfortunately, this is a tactic that has not been shown to work, at least not for all diseases. A 2015 meta-analysis in the journal Psychological Bulletin looked at all the research on fear messaging. The authors found that fear appeals could change attitudes, intentions and behaviors, but mostly on issues with a high susceptibility and severity. With respect to hypertension, it’s hard to believe we’re not already oversaturated with worry.

Fear messaging also works better when it’s intended to change one-time-only behaviors, not lifestyle or long-term activities. Most “new” people with high blood pressure should focus on how they live. The truth, unfortunately, is that it’s just easier to put people on medication than try to get them to modify their long-term behavior.

More people will probably be prescribed drugs because they’ve been told to be afraid and because they can’t get their blood pressure low enough with diet and exercise.

The potential upside from this change is that because of “awareness,” more people might make lifestyle changes that lead to lower cardiovascular risk in the future. The potential downside is that more people may receive a diagnosis of high blood pressure, be overtreated with medication, and endure side effects or adverse outcomes. It’s not irrational to fear that these new guidelines might lead to more of the latter than the former.

December 19, 2017

Can insurers sue to recover cost-sharing money?

Murray-Alexander is going nowhere. Senator Collins insists that passing the bipartisan legislation, which would restore cost-sharing payments for two years, is a condition of her vote on the pending tax bill. But she appears willing to accept airy promises that Senate leadership will make the bill a priority.

Never mind that House Republicans have no intention of passing the bill and that Democrats have ruled out cooperating if the individual mandate is repealed. Never mind, too, that the Democrats’ threat is credible: they don’t stand to gain much if the bill is passed. By and large, insurers have already adjusted to the loss of the cost-sharing subsidies.

How exactly have they adjusted? Most states instructed insurers to anticipate the withdrawal of the cost-sharing payments and to concentrate the resulting premium hikes on silver plans. Because the ACA caps the premiums that people receiving subsidies have to pay for insurance, those price spikes won’t harm most exchange customers. To the contrary, most are better off. Premium subsidies increase as the price of silver plans go up, so gold and bronze plans—whose premiums won’t increase on account of the funding cut-off—are more affordable than they otherwise would be.

In other words, “silver loading” has mitigated much of the fallout from the loss of the cost-sharing subsidies. If Congress appropriated the cost-sharing money now, it’d be a windfall for insurers. Why should Democrats throw their support behind a bill that won’t stabilize the markets and would give the Republicans cover for repealing the mandate?

* * *

If I’m right that Murray-Alexander is a dead man walking, the cost-sharing money won’t be appropriated for 2018. That, in turn, gives rise to an interesting legal question.

As I first pointed out back in 2015, insurers can sue in the Court of Federal Claims to recover their cost-sharing payments. It’s a simple lawsuit: insurers were promised some money; the federal government reneged; and the insurers want damages on account of the breach. The payment of court-ordered damages can come out of the Judgment Fund, even without an appropriation to make the payments in the normal course.

The law is clear; the lawsuit practically writes itself. Insurers should have no trouble recovering the money owed for the last months of 2017—about $1 billion. But what about the money owed for 2018 and beyond?

As a first cut, it seems that insurers should still be able to recover. In a typical breach of contract claim, the courts aim to put a non-breaching party in the same position it would have been in if the breaching party had kept its promise. Here, Congress promised to reimburse insurers for giving their low-income customers a discount on out-of-pocket payments. Insurers are still giving those customers a discount, but the government has refused to pay.

The proper measure of expectation damages, then, is the full amount of promised reimbursement. That amount will continue to accrue for every month that Congress refuses to appropriate the money. If that’s right, the question isn’t whether Congress will pay the cost-sharing payments. It’s when.

But matters may not be so simple. In measuring damages, the Court of Federal Claims will also inquire into mitigation—a principle that might be familiar to you if you’ve ever thought about breaking a lease on an apartment. Although your landlord can sue you for any rent owed for the months remaining on the lease, he also has a duty to find a new tenant. If he does, you only have to compensate your landlord for the time that the apartment was empty. The landlord has mitigated his losses.

The same principle should kick in here. Silver loading has allowed insurers to sidestep most of the harm associated with the loss of the cost-sharing subsidies. Insurers haven’t hemorrhaged customers; instead, they’ve adapted. Indeed, some insurers are better off now than they were before: as premium subsidies increase, they’ll get more customers signing up for their gold and bronze plans.

In short, insurers have mitigated a large part of their losses. Giving them the full amount of the cost-sharing money wouldn’t put them in the same position they would have been in if the federal government adhered to its promise. It would give them a windfall. Contract law doesn’t require the courts to make contracting parties even better off than they would have been in the absence of a breach.

* * *

That doesn’t mean that insurers will lose. The default rule is still that insurers should be paid what they were promised, and the onus is on the government to prove that they’ve mitigated their losses. That’s not an easy burden to discharge: it’s hard to know what the world would have looked like if the cost-sharing payments had been made, so it’s hard to know whether any given insurer is better off or worse off now that they’ve been terminated. The factual inquiries will be demanding.

My tentative sense, however, is that insurers shouldn’t be too bullish about recovery. One reason can be found in Murray-Alexander itself. As currently written, the bill would require state insurance commissioners to develop plans to provide rebates to customers and the federal government. Why? Because funding the cost-sharing payments for 2018 would otherwise give insurers a huge windfall.

Allowing insurers to recover their money in court would give them an identical windfall. The courts aren’t likely to stand for that.

December 18, 2017

Healthcare Triage: The Trump Administration’s Plans for Medicare Premium Support

Senior Trump Administration official Seema Verma has written that Medicare is in financial trouble, and one step in fixing it is giving consumers “incentives to be cost-conscious.” This may be coded language for something called premium support for Medicare, which boils down to patients paying more, and the government cutting funding for medicare.

This episode was adapted from a column Austin wrote for the Upshot. You can find the article and the sources here.

Enjoining the contraception rules

On Friday afternoon, a district court in Pennsylvania enjoined the Trump administration’s new rules on contraception coverage from taking effect. The court’s ruling was not unexpected: I’d argued earlier that the rules were vulnerable on both procedural and substantive grounds, and the court’s analysis largely tracks my own.

Procedurally, the Trump administration had no good explanation for why it skipped notice and comment:

There was no deadline, much less an urgent one, to implement new rules. The [rules] did not resolve any uncertainty and … have not prevented ongoing litigation. And the blizzard of prior comments that [HHS has] received in past rounds of notice and comment rulemaking actually demonstrates that further comments are necessary given the public interest in this matter.

The sloppiness here is striking. HHS could have run through the notice-and-comment period on an expedited timeframe. Doing so would have delayed the rules by a few months, but probably no more than that. Instead, the Trump administration practically begged the courts to step in.

Barring a successful appeal, the Trump administration will now have to start all over. And appealing is risky. HHS apparently thinks that time is of the essence here. Yet, if the agency appeals and loses, it will have wasted another year before even starting notice and comment. At best, HHS might issue final rules sometime in the middle of 2019. At worst, the timeline could slip to 2020.

And make no mistake about it: the agency likely will lose on appeal, at least if the district court is right that the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania has standing to sue. (That’s a hard question.) The procedural violation here is basic stuff, and the Trump administration’s justifications for skipping notice and comment are almost laughably thin. Maybe the agency should swallow the loss and start over now.

* * *

Then again, HHS may have no choice but to appeal. The district court didn’t just criticize the agency for the procedural violation. It also held that the Trump administration’s rules suffered from two substantive problems. First, the court concluded, as I had, that the agency lacked even a colorable basis for exempting employers with non-religious “moral objections” to contraception coverage.

The Moral Exemption Rule allows any non-profit or for-profit organization that is not publicly traded to deny contraceptive coverage for its employees for any sincerely held moral conviction. This means that boards of closely held corporations can vote, or their executives can decide, to deny contraceptive coverage for the corporation’s women employees not just for religious reasons but also for any inchoate—albeit sincerely held—moral reason they can articulate. Who determines whether the expressed moral reason is sincere or not or, for that matter, whether it falls within the bounds of morality or is merely a preference choice, is not found within the terms of the Moral Exemption Rule.

The court found no statutory basis—because none exists—for such a sweeping exception to the ACA’s mandatory requirement.

Second, the court didn’t believe that HHS had the authority, under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, to expand the Obama-era accommodation for employers with religious objections. In prior litigation, the Third Circuit had held that the Obama-era accommodation passed muster under RFRA. The court reasoned that RFRA therefore couldn’t justify transforming the accommodation into a free-wheeling exemption to the ACA.

I’m not sure what to think of this argument. It has a certain logical coherence, but it implies that agencies have, at most, a highly circumscribed role in crafting RFRA-sensitive accommodations to their rules. That might be appropriate: Congress didn’t delegate to every agency under the sun the authority to interpret and implement RFRA.

Nonetheless, the reasons that we think it’s a good idea to defer to agencies—that they’re experts in their regulatory domain and that they’re more politically accountable than the courts—apply equally here as elsewhere. And courts often defer to agencies’ judgments about how the laws that they’re charged with administering align with generally applicable legal rules.

When it comes to the Supremacy Clause, for example, the courts give “some weight” to an agency’s conclusion that a state law impairs federal objectives and must therefore give way: “The agency is likely to have a thorough understanding of its own regulation and its objectives and is ‘uniquely qualified’ to comprehend the likely impact of state requirements.” For similar reasons, shouldn’t the courts give “some weight” to an agency’s conclusions that RFRA demands a particular accommodation?

* * *

These are deep waters; I don’t pretend to know the right answer yet. For now, the important point is that HHS will have to appeal at least the RFRA portion of the district court’s order if it hopes to reestablish the exemption for religious organizations.

One final issue to ponder. The court’s order says simply that defendants “shall be enjoined from enforcing the new [rules].” On its face, the order doesn’t specify whether it applies on a nationwide basis, only in Pennsylvania, or only with respect to Pennsylvania as an employer. My hunch is that it’s the first: district courts over the past couple of decades have made a habit of entering nationwide injunctions. (As Sam Bray argues in a compelling article, that’s an unfortunate and damaging development.) But the order itself doesn’t say, and the Trump administration may need to ask the district court to clarify.

The bottom line, though, is that the Trump administration’s needless haste has imperiled one of its signature initiatives. However you feel about the new rules—and I think that reasonable minds can differ on that front—the incompetence on display here is breathtaking.

Aaron E. Carroll's Blog

- Aaron E. Carroll's profile

- 42 followers