Aaron E. Carroll's Blog, page 112

February 21, 2018

A Substantial Gap in Many Medicaid Programs: Lack of Dental Benefits

The following originally appeared on The Upshot (copyright 2018, The New York Times Company).

Even before any proposed cuts take effect, Medicaid is already lean in one key area: Many state programs lack coverage for dental care.

That can be bad news not only for people’s overall well-being, but also for their ability to find and keep a job.

Not being able to see a dentist is related to a range of health problems. Periodontal disease (gum infection) is associated with an increased risk of cancer and cardiovascular diseases. In part, this reflects how people with oral health problems tend to be less healthy in other ways; diabetes and smoking, for instance, increase the chances of cardiovascular problems and endanger mouth health.

There is also a causal explanation for how oral health issues can lead to or worsen other illnesses. Bacteria originating in oral infections can circulate elsewhere, contributing to heart disease and strokes. A similar phenomenon may be at the root of the finding that pregnant women lacking dental care or teeth cleaning are more likely to experience a preterm delivery. (Medicaid covers care related to almost half of births in the United States.)

“I’ve seen it in my own practice,” said Sidney Whitman, a dentist who treats Medicaid patients in New Jersey and also advises that state and the American Dental Association on coverage and access issues. “Without adequate oral health care, patients are far more likely to have medical issues down the road.”

There are also clear connections between poor oral health and pain and loss of teeth. Both affect what people can comfortably eat, which can lead to unhealthy changes in diet.

But the problems go beyond health. People with bad teeth can be stigmatized, both in social settings and in finding employment. Studies document that we make judgments about one another — including about intelligence — according to the aesthetics of teeth and mouth.

About one-third of adults with incomes below 138 percent of the poverty level (low enough to be eligible for Medicaid in states that adopted the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansion) report that the appearance of their teeth and mouth affected their ability to interview for a job. By comparison, only 15 percent of adults with incomes above 400 percent of the poverty level feel that way.

Some indirect evidence of the economic effects of poor oral health comes from a study of water fluoridation, which protects teeth from decay. It found that fluoridation increased the earnings of women by 4 percent on average, and more so for women of low socioeconomic status.

Other evidence comes from a randomized study in Brazil. In that study, investigators showed one of two images to people responsible for hiring: pictures either of a person without dental problems or with uncorrected dental problems. Those with dental problems were more likely to be judged as less intelligent and were less likely to be considered suitable for hiring.

The relationship between oral health and work has gained new salience in light of Kentucky’s recently approved Medicaid waiver, which permits the state to impose work requirements on some able-bodied Medicaid enrollees. It’s a step that some other states are also considering.

Medicaid takes different forms in different states, and even within states, different populations are entitled to different benefits. Though all states must cover dental benefits for children in low-income families, they aren’t required to do so for adults.

As of January 2018, only 17 state Medicaid programs offered comprehensive adult dental benefits, and only 14 of those did so for the population eligible for Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act. More typically, states offer only limited dental benefits or none.

Dental coverage under most private health care plans isn’t comprehensive, either — people who want it have to buy separate dental plans. But compared with those enrolled in private coverage through an employer or on their own, the population eligible for Medicaid is much more likely to need dental care and much less likely to be able to afford it or coverage for it. People with incomes low enough to qualify for Medicaid are twice as likely to have untreated tooth decay, relative to their higher-income counterparts.

Kentucky offers limited dental benefits to Medicaid enrollees, including those on whom work requirements would be imposed. Those benefits exclude coverage for dentures, root canals and crowns, which could challenge some enrollees’ ability to maintain good oral health and lead to greater emergency department use.

One study found that after Kentucky’s Medicaid expansion in 2014, the rate of use of the emergency department for oral health conditions tripled. Another study found that about $1 billion in annual emergency department spending was attributed to dental conditions, and 30 percent of emergency department visits for dental problems were made by people enrolled in Medicaid.

Other states that have proposed imposing work requirements as a condition of Medicaid eligibility include Arizona, Arkansas, Indiana, Kansas, Maine, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Utah and Wisconsin. Of these, only North Carolina and Wisconsin offer extensive dental benefits, while Arkansas, Indiana and Kansas offer limited benefits. (The definition of “limited” varies by state, but in all such states benefits are capped at $1,000 per year and cover less than 100 of 600 recognized dental procedures.) Maine, New Hampshire and Utah offer emergency-only benefits. Arizona offers none.

Though emergency-only coverage is less than ideal, it is better than nothing, as documented in a recent study based on Oregon’s Medicaid experiment. The study used a random lottery to offer some low-income adult residents eligibility for Medicaid. At the time of the study, Oregon offered dental coverage only for emergencies..

The study found that one year after the lottery, Medicaid coverage meant more people got dental care (largely through emergency department use), and the percentage of people reporting unmet dental needs fell to 47 percent from 61 percent. It also doubled the use of anti-infectives, which are used to reduce gum infections. Another study, published in the Journal of Health Economics, found that Medicaid dental coverage increased the chances that Medicaid-eligible people had a dental visits by as much as 22 percent.

It’s an accident of history that oral care has been divided from care for the rest of our bodies. But it seems less of an accident that the current system hurts those who need it most.

February 20, 2018

AI Rifles and Future Mass Shootings

The scale and frequency of mass killings have been increasing, and this is likely to continue. One reason — but just one — is that weapons are always getting more lethal. One of the next technical innovations in small arms will be the use of artificial intelligence (AI) to improve the aiming of weapons. There is no reason for civilians to have this technology and we should ban it now.

By lethality, I mean how many people you can kill in a short period. Lethality depends on many factors, including the weapon’s rate of fire, but not just that. Depending on the circumstances, a shooter with a highly accurate bolt-action rifle may be able to kill more people than one with a fully automatic but inaccurate weapon. Life, as they say, is a trade-off.

However, accurate shooting is hard. Bullets fall as they travel, so you need to estimate the distance to the target and compensate by pointing the barrel up. Likewise, bullets are blown by the wind, so you have to measure that and compensate for it. Finally, it’s difficult to hold a rifle stationary, but if you are even a minute of angle off of true aim when you pull the trigger, at 500 yards range you will be several inches off when the bullet reaches the target.

Here is a rifle that uses AI to increase rifle accuracy (see also here). It automatically carries out drop and wind compensation and times the moment of firing so that the barrel is pointed optimally to hit the target.

Made by TrackingPoint, a start-up based in Austin, Texas, the new $22,000 weapon is a precision-guided firearm (PGF). According to company president Jason Schauble, it uses a variant of the “lock-and-launch” technology that lets fighter jets fire air-to-air missiles without the pilot having to perform precision aiming.

The PGF lets the user choose a target in the rifle’s sights while the weapon decides when it is the best time to shoot – compensating for factors like wind speed, arm shake, recoil, air temperature, humidity and the bullet’s drop due to gravity, all of which can affect accuracy.

To do this, the PGF’s tracking system includes a computer running the open-source Linux operating system, a laser rangefinder, a camera and a high-resolution colour display in an integrated sighting scope mounted on top of the weapon. The user simply takes aim and presses a button near the trigger when a dot from the laser illuminates the target.

The computer then runs an algorithm using image-processing routines to keep track of the target as it moves, keeping the laser dot “painted” on the same point. At the same time, the algorithm increases the pressure required to pull the trigger, only reducing it when the gun’s crosshairs are right over the laser dot – and the bullet is then fired.

The Tracking Point XS-1 precision-guided firearm.

The US and other militaries are developing similar weapons. The Tracking Point rifle appears to be something that Americans can legally own. The technology will, of course, continue to improve and will get cheaper.

At some point, shooters with rifles like these will begin finding positions overlooking busy city streets, arenas, and schoolyards. Although they will fire at slower rates than the Las Vegas shooter did, far higher proportions of their shots will be fatal.

Or, Americans could decide that only the military and the police need these weapons. The time to make this decision is now before the devices get into circulation.

Someone will say that mass shooting are rare. Moreover, if a future schoolyard shooter can’t get an AI rifle, he will use an only marginally less lethal weapon. Thus, preventing civilians from legally owning AI rifles would save only a few lives and only trivially reduce the total of gun deaths. So, really, aren’t you just virtue-signalling?

So what? No one who isn’t serving in the military or police needs an AI rifle more than those future victims need their lives.

February 15, 2018

Can mental health policy solve the problem of mass shootings?

Some people argue that mass shootings in America result from mental health problem and require mental health policy solutions. Can this work?

Let’s think through the possible mental health policies for preventing mass shootings. I see three: 1) we could reduce the social determinants of mental illness to lower the population prevalence of mental disorders, 2) we could increase the availability of treatments for mental illnesses, and 3) we could attempt to identify the specific individuals likely to kill and get them into treatment.

1. Reduce the population prevalence of mental illness. Mental illness is associated with social adversity. The causality runs both ways: getting ill will hammer your life and, conversely, falling down the social gradient substantially increases your risk of getting ill. Providing more and better jobs and improving the social safety net would raise the well-being of Americans and, plausibly, reduce the population prevalence of mental and substance abuse disorders.

However, the causal association between mental illness and mass killing is weak. Few mentally ill people ever kill anyone. A mentally ill person is, at worst, only slightly more likely to be violent than anyone else. Conversely, it is not clear how many mass shooters were mentally ill. So even a substantial reduction in the prevalence of mental illness would have only a small effect on the number of mass shootings.

2. Increase the availability of mental health treatments. Let’s stipulate that if you are mentally ill and you are at risk of carrying out a massacre, mental health treatment might help you avoid this tragedy. Access to mental health treatment could be increased by training more evidence-based mental health providers, insuring the uninsured, and requiring that health insurance cover mental health treatment.

Unfortunately, the effect of increased access on mass shootings would be limited, because a) it’s likely that many potential shooters are not mentally ill; b) even with improved access, not all mentally-ill potential killers will seek treatment; and c) mental health treatment doesn’t always work.

Policies 1 and 2 are eminently worth pursuing because they would reduce mental illnesses and the suffering they entail. However, they would be expensive, and few of the politicians who talk about mental health as a response to mass killing support these policies. In any event, these strategies would have at best small effects on mass murders.

3. Identify likely mass shooters and deliver mental health care to them. This policy is a non-starter because of the mathematics of prediction. Murderers are too rare in the population. Any conceivable prediction model will generate overwhelming numbers of false positives. There is no Minority Report future world.

In summary: America needs better mental health care. However, the nation is unlikely to make the required effort, and if it did, it wouldn’t have much effect on mass shootings.

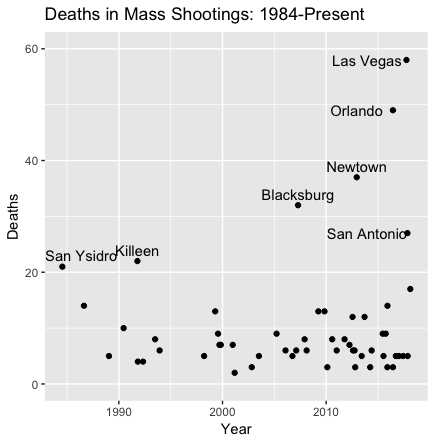

I have updated my graphs of mass shootings to include yesterday’s killings in Parkland, FL, but nothing in the overall pattern has changed. This graph plots the number of deaths in shootings that killed more than four people.

This plot only labels shootings that killed 20 or more, so Parkland with only 17 doesn’t get a label. It is, oxymoronically, a routine massacre. As someone noted on Twitter yesterday, it’s a bitter irony that the 1929 Valentine’s Day Massacre involved only seven murders.

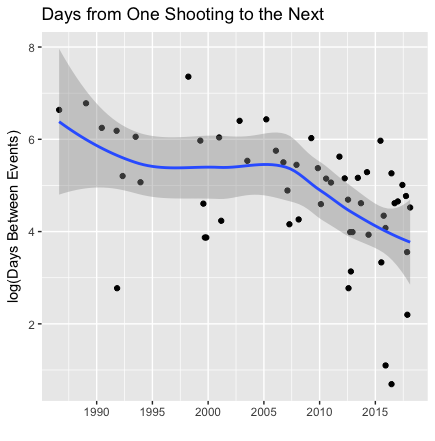

The next graph plots the logarithm of the number of days between successive mass shootings against time and adds a smoothed curve. The declining curve starting in about 2007 indicates that mass shootings are happening increasingly frequently.

Point and counterpoint on the recent NEJM 340B study

Last week, the American Hospital Association (AHA) posted a critique of a recent, NEJM-published study by Sunita Desai and Michael McWilliams examining the effects of the 340B Drug Pricing Program, which has the goal of enhancing care for low-income patients. That AHA critique links to a methodological review by economist Partha Deb of the study’s methods. (Partha Deb was kind enough to speak with me and disclosed that he was compensated by the AHA for his time to prepare his review. At the time we spoke, that financial relationship was not disclosed in his online review, something he said he would try to correct.)

The study used a regression discontinuity design, exploiting a threshold in the program’s eligibility rules for general acute hospitals — hospitals with disproportionate share hospital (DSH) adjustment percentages greater than 11.75% are eligible for the program. The study findings suggest that the 340B Program has increased hospital-physician consolidation and hospital outpatient administration of intravenous and injectable drugs in oncology and ophthalmology, without clear evidence of benefits for low-income patients.

As Desai and McWilliams note in their paper, the study had several limitations. One that holds for all regression discontinuity studies is that the estimates pertain to hospitals close to the threshold. Another is that the study relies on data from Medicare and the Healthcare Cost Report Information System. The AHA claims that these limitations and other issues raised by Deb constitute “major methodological flaws” that “negate” the study’s findings.

In a subsequent post, the AHA suggests that the study was unnecessary because the authors could have just asked hospitals how they were using resources generated from the 340B Program.

The authors’ sent me a response to these critiques, which I have agreed to host here at TIE. I will let that response speak for itself. Read it.

But I do want to make two additional comments. First, the notion that we should only learn how a program works by “just asking” those that participate in it or benefit from it is absurd. To be sure, much insight can be gained from such qualitative work. But independent, objective, quantitative work is also essential to unbiased assessment of programs. I reject the AHA’s dismissal of research on these grounds.

Second, there is something troubling to me about advocacy organizations hiring top academics to critique specific studies. The potential for conflicts of interest is obvious. That is not to say there is anything wrong with Deb’s critique, but it is hard to know, in general, what role the financial relationship plays in these kinds of situations. At a minimum, that financial relationship should be disclosed.

Healthcare Triage News: But, But, Medicaid Recipients Are Already Working

Recently, the Trump administration put forward plans to force all the able-bodied lazy people with Medicaid coverage to finally get jobs. The problem with this is that pretty much all the Medicaid recipients who can work already have jobs. So, how’s all this going to work?

February 13, 2018

A new study finds cost shifting, but I’m skeptical

A new NBER working paper by Michael Darden, Ian McCarthy, and Eric Barrette claims to have found evidence of hospital cost shifting. I’m not so sure.

I will skip the throat clearing about what hospital cost shifting is, why or when we should or should not expect it to occur in theory, and what the prior literature says in some detail about whether it occurs in practice. Go read this Upshot post and all it links to for that. I will only say that based on the prior literature, we should begin consideration of the new paper with some skepticism about claims of cost shifting — it is reasonable to believe it doesn’t happen.

Therefore, even to find, with credible methods, a modest degree of cost shifting — like $0.10 per dollar of public payer shortfall is shifted to private payers — would be a big deal.

What Darden et al. found isn’t modest. It’s huge. They estimated that more than half of Medicare payment shortfalls are recouped by jacking up prices charged to private insurers — 56 cents on the dollar, to be precise. Yow! (Right here you should wonder why hospitals would stop at 56 cents on the dollar. If your answer is, “that’s the limit of their market power,” you’re on the right track. That also means they’ve exhausted their market power and, unless they acquire more, cost shifting should halt. And right there is why more than rare claims of cost shifting aren’t credible.)

But, without even looking at methods, we should be careful about taking this figure to mean that there really is cost shifting at a rate of 56 cents on the dollar. Given prior work, a Bayesian might, at most, update his/her thinking from “there is no cost shifting” to “there could be a little cost shifting.” However, the methods might not even warrant that.

So, what’s up with the methods? Craig Garthwaite did a nice pointing out a few issues, starting with this tweet:

There have been a bunch of tweets about the new cost shifting paper this morning. I have a couple of thoughts we should keep in mind. First, finding evidence of cost-shifting is hard at least in part because finding the right setting for testing for its presence is hard (1/4)

— Craig Garthwaite (@C_Garthwaite) February 12, 2018

Let’s unpack a few of his concerns, which I share. First of all, the headline result of massive cost shifting is based on examining how private hospital prices change due to changes in hospitals’ Medicare penalty status. That is, Medicare financially penalizes hospitals for lower quality in several ways, which the paper examines. The study found that hospitals that change from not-penalized to penalized status increase their private prices more than hospitals that don’t. From that, they back out a cost shift rate of 56 cents on the dollar.

But there’s another way to estimate what the cost shift rate is, not by looking at changes in penalty status, but by looking at what the penalty amount is. How much does a hospital cost shift when it is penalized an additional dollar? When estimated this way, the authors find small and statistically insignificant evidence of cost shifting, which is a highly credible finding on its face. (See footnote 17 of the paper.)

So, one has to ask, why might hospitals that become penalized differ from those that don’t, and in ways that are associated with increases in private prices? About this, Craig made a very good point: Hospitals were aware in advance of their risk of being penalized. Those that looked like they would be may have invested more in quality improvements. For some, those improvements didn’t translate into avoiding the penalty, but they did increase the value those hospitals were delivering. Private payers may have been willing to pay more for that additional quality. It’s possible they’re even willing to pay more for investments in quality that haven’t yet translated into actual improvements.

Separately, it’s also possible that hospitals that respond to potential penalties change their marginal costs, which would change their profit- (or revenue-) maximizing price. This could look like cost shifting, but it’s still a response to a change in quality or, more generally, cost structure. It wouldn’t be a response to Medicare reimbursement shortfalls in the sense that if Medicare just cut payments without linking them to quality, one would not expect the same change in private prices.

The BIG IDEA here is that firms (here, hospitals) respond to incentives in ways that change their production function (their costs and the value they provide). In fact, this is the point of Medicare quality penalty programs. They should affect what hospitals do and that, itself, can affect prices, as explained above. That’s not cost shifting. Not being able to control for that in a cost shifting study is a big problem. The particular approach taken in this paper likely doesn’t address this problem, leading to estimates that should not be attributed to cost shifting.

I will close by adding that this paper is highly useful for tracking down claims of cost shifting made by hospital executives and policymakers. See the main text as well as footnote 1.

PS: I should make explicit what should be obvious. I would appear to have a large interest in arguing away findings of hospital cost shifting, given my prior writing on the issue. I am so aware of that apparent conflict that I had a few colleagues without that conflict look over this post before publishing. All of their input was incorporated to their satisfaction.

Healthcare Triage: The Ups and Downs of Evidence-Based Medicine

This week on HCT, we’re talking about evidence-based medicine. We talk about it a lot here on the show, but what exactly does the term mean? Why is evidence-based medicine useful, and what can we do to use it more effectively?

February 7, 2018

Healthcare Triage: Blood Pressure Guidelines Have Changed, and PANIC!

Actually, don’t panic. Or maybe do panic. I don’t know. The American Heart Association released new blood pressure guidelines late last in 2017. New coverage was breathless, and claimed millions of Americans suddenly had high blood pressure. But, it’s a little more complicated than that.

JAMA Forum: The economy and health

It’s important to recognize that the financial effects of a shrinking or growing economy—employment and reduced income—can accrue to different people than its health effects. This is demonstrated in an intriguing study by Ann Stevens, PhD, Douglas Miller, PhD, Marianne Page, PhD, and Mateusz Filipski, PhD. They found that increases in mortality during strong economic conditions are concentrated among the elderly, particularly older women living in nursing homes. One mechanism for this phenomenon is that employment levels in skilled nursing facilities—particularly for nursing staff—go down when the unemployment rate falls. This might occur because nurses who would otherwise work in those facilities are able to find better jobs elsewhere, or their other household members are able to gain employment. Moreover, it may be the case that during economic expansions, the nursing staff that facilities are able to retain are of lower quality. Since quality is positively correlated with nursing home staff levels, this connection between employment rates and nursing home mortality is plausible.

That’s from my latest on the JAMA Forum. Go read the rest!

February 1, 2018

Healthcare Triage News: The Flu is Terrible!

This year’s influenza is really bad. Hospitalizations are up, and health departments in 49 states report widespread flu. Apparently, if you don’t want the flu, go to Hawaii. Just kidding. You can still get a flu shot, and you don’t have to go to Hawaii!

Aaron E. Carroll's Blog

- Aaron E. Carroll's profile

- 42 followers