Aaron E. Carroll's Blog, page 111

March 6, 2018

Healthcare Triage: Why Does the U.S. Spend So Much on Healthcare? High, High Prices.

American healthcare spending is still WAY higher than pretty much all other industrialized countries. But not that long ago, things were different. The US didn’t spend nearly as much in this realm. What changed? Demographics? More sickness? Nah. Spoiler alert, prices have risen much, much faster than the rate of inflation. We’ve got a few suggestions for getting it under control.

This video was adapted from a column Austin and I wrote for the Upshot. Links to further reading can be found there.

March 5, 2018

A feeble constitutional challenge.

I was gone last week when twenty states filed yet another lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of the Affordable Care Act. But no matter. This case isn’t going anywhere—or at least it shouldn’t go anywhere.

In their complaint, the states point out (rightly) that the Supreme Court upheld the ACA in NFIB v. Sebelius only because the individual mandate was a tax and (rightly) that Congress has now repealed the penalty for going without insurance. As the states see it, the freestanding requirement to get insurance, which is still on the books, is therefore unconstitutional. Because it’s unconstitutional, the courts must invalidate the entire ACA—lock, stock, and barrel.

If that sounds crazy, that’s because it is. Even if a penalty-free mandate is unconstitutional—and reasonable minds can differ on that score—the ACA’s elimination isn’t the proper remedy. Ilya Somin—no fan of the law—ably explains why at the Volokh Conspiracy.

[T]he Court has held that if the unconstitutional part of a law is so important to the rest that the statute as a whole cannot work as intended, then the latter falls along with the former. Otherwise, the residual law is no longer what Congress had intended to set up. …

But there is a big difference between a court choosing to sever a part of a law, and Congress doing so itself. And in this case, Congress has already effectively neutered the individual mandate, while leaving the rest of the ACA in place. It was Congress that removed the monetary penalty imposed on violators of the individual mandate, thus rendering it ineffective. And it was also Congress which chose to leave the rest of the law in place, nonetheless (largely because President Trump and the GOP leadership repeatedly failed to round up enough votes in the Senate to repeal any more of Obamacare). Unlike in NFIB, a court could not conclude that Congress’ design for the ACA would be fatally undermined without an effective individual mandate. … In this case, Congress itself has concluded that a mandate-less ACA is acceptable (or at least a lesser evil than the available alternatives).

The states also argue that a mandate-less ACA is unconstitutional because it lacks a rational basis. That’s nuts too. Repealing the mandate may be bad policy, but it’s not arbitrary in any constitutional sense, for at least three different reasons.

First, several states prior to the ACA adopted community rating and guaranteed issue—but did not adopt a mandate. New York and Massachusetts spring to mind: the latter eventually adopted a mandate, but the former never did. As policy, these state schemes suffered from predictable problems associated with adverse selection. But they weren’t irrational in any constitutional sense. Neither is the ACA.

Second, and more importantly, the ACA uses both carrots (premium tax credits and cost-sharing protections) and sticks (the mandate) to push healthy people into the individual market. Even without the stick, however, the carrots are enough to get lots of healthy people to buy coverage. If you make $30,000 a year, for example, you can buy health insurance on the exchange for about $250 a month. Lots of healthy people will take that deal, which is why the exchanges will be resilient even without the mandate. The CBO confirms as much: it estimates that federal spending on subsidies will fall from $887 billion over ten years to $702 billion, a decline of just 20%. That $702 billion will subsidize coverage for millions of people in the individual market.

Third, and more subtly, the elimination of the federal mandate doesn’t imply the elimination of state mandates. And many states—nine at the last reckoning, but likely more—are now considering the adoption of replacement mandates. Whether or not they follow through, it’s hardly irrational to vest in the states the authority to weigh the tradeoffs associated with a mandate. Indeed, Republicans claimed in the debates over repeal and replace that they were committed to federalism. Repealing the mandate partly follows through on that commitment.

* * *

The weakness of the states’ case raises questions about why the lawsuit was brought at all. Ilya Somin thinks the states want to vindicate what he calls “an important constitutional principle”: that “the federal government cannot use its tax power to impose mandates unless that mandate includes a monetary fine that raises some revenue for the government.” In what world, though, is that principle an important one? Is there some risk that Congress might otherwise adopt a raft of hortatory, penalty-free mandates? Even if it did, why should anyone care?

What the case does, instead, is force the Trump administration to decide whether it will defend the ACA from constitutional attack. The Justice Department has an entrenched, longstanding, and bipartisan commitment to defending congressional statutes if reasonable arguments can be made in their defense. It’s a bedrock convention of our constitutional structure, one that prevents the executive branch from using litigation strategy to undo Congress’s handiwork.

The Trump administration, however, doesn’t always seem to care for quaint legal conventions. It also loathes the ACA. Plus, Republicans can point to the Obama administration’s refusal to defend the Defense of Marriage Act as precedent. Don’t get me wrong, the two cases can be distinguished: refusing to defend a law that countenanced overt discrimination against a disfavored group is different from refusing to defend one that regulates health insurance. But that’s the thing about precedent. It can be stretched.

The real-world consequences of refusing to defend would be hard to predict. They might be minimal. The courts can and probably will appoint lawyers to defend the ACA, as Somin points out. (For the record, I’m happy to volunteer for that job—it’s the sort of thing I used to do when I worked for the Justice Department.) So the final outcome of the litigation shouldn’t change.

But declining to defend the ACA could have implications for whether the Trump administration chooses to enforce it. That’s a question that has become urgent with Idaho’s decision to flout the law. Unless HHS intervenes, other states will likely follow its lead. It’d be much harder for HHS to step in if the Justice Department takes the position that the whole law is unconstitutional.

At the end of the day, though, the biggest risk isn’t to the ACA. The future of health reform will turn on future elections, not this lawsuit. The biggest risk, instead, is that the litigation will further erode the norm that the executive branch must respect, enforce, and defend duly enacted statutes.

Already, I fear that the tumult over health reform over the last eight years has undermined some of our basic assumptions about the rule of law. Maybe the states that have bought this vexatious lawsuit don’t care about that. Maybe they’re willing to pay any price to hurt the ACA. But I, for one, am worried.

March 2, 2018

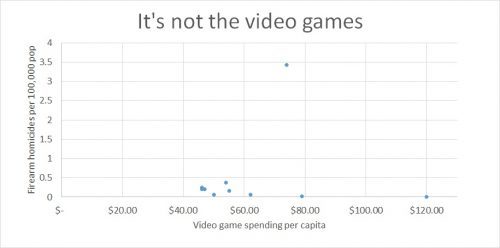

Video games and firearm homicides

I’m too tired to argue. Some have suggested that the reason we have so many gun deaths in the US is because of video games. So here’s a chart. On the x-axis you have video game spending per capita for the top ten countries in the world. On the y-axis you have firearm homicides per 100,000 pop. I don’t think it’s the video games causing gun homicides. YMMV.

Data:

Video game spending per capita

Firearm homicides per 100,000 pop

Japan

$ 120

0

Korea

$ 79

0.02

USA

$ 74

3.43

UK

$ 62

0.06

Australia

$ 55

0.16

Canada

$ 54

0.38

Germany

$ 50

0.07

Switzerland

$ 47

0.21

France

$ 46

0.21

Ireland

$ 46

0.25

March 1, 2018

Healthcare Triage News: The Longer Term Impact of Short Term Plans

The Trump administration can still do plenty to mess with the Affordable Care Act. We warned about that in many episodes, and it’s coming to pass.

February 28, 2018

Heathcare Triage: Preventive Care is Good, Even Though It’s Not Saving Money

The idea that spending more on preventive care will reduce overall health care spending is widely believed and often promoted as a reason to support reform. Unfortunately, that doesn’t pan out in real life.

This episode was adapted from a column I wrote for the Upshot. Links to further reading and sources can be found there.

Help me learn new things in 2018 – Rome!

This post is part of a series in which I’m dedicating a month to learning about periods in history this year. The full schedule can be found here. This is month one. (tl;dr at the bottom of this post)

This month was a bit surprising in that I the parts I thought I would enjoy the most and the parts I thought I would enjoy the least were somewhat reversed. Let me start by saying that I wasn’t ignorant about Rome before I read this month. I took a gazillion years of Latin in middle school and high school, and I’ve even read Virgil’s Aeneid in the original Latin. Not well, mind you (I’ve got a great story about the AP Latin test where I mixed up a mountain and a tree, and… forget it).

I’ve also always loved the architecture of Rome, and am well versed on the period of Cicero, to Caesar, into the emperors. That said, there was still plenty to learn.

I started the month with Mary Beard’s SPQR, which is every bit as good as everyone says it is. She begins the book by focusing on Cicero, which is a great idea, and then backs up to the beginning (Romulus and Remus!) and moves forward through the emperors. That’s a lot of ground to cover, and she does it fairly well. One of the things I appreciated the most was how she spent time talking about how we know what we know. There are no videos or news reports, obviously. Much of what we get is through what was written down and survived. It’s critical to remember that there were no printing presses. Things has to be hand copied or written many times.

One of the reasons we know so much about Cicero is that, as a politician, he would print up many, many copies of his speeches. He knew not everyone would come to hear him, so he had some infrastructure to write those things down and distribute them to people. Smart. Also, good for history.

A couple key players in history also spent a lot of time writing their memoirs. That’s why we know so much about them. If you didn’t take the time to do that… well, then you have even less control of who tells your story.

Beard’s book gives you a pretty good sense of the time, and does a good job of making you realize that life in ancient Rome, while certainly more precarious than now (politicians get killed way too often for comfort and you spent a lot of time fighting in wars), it was also reasonably comfortable at times. More on that in a bit. She also reminds you that the periods we focus on (Caesar +) are only a blip in the history of Rome.

Next I read Mike Duncan’s The Storm Before the Storm, which I wish I’d read first. That’s because his book focuses on the period right up to Caesar et al, and is a much more in depth history of Rome before what we know. I mean WAY more in depth. There were a hell of a lot of wars, and a hell of a lot of political intrigue before the Republic.

Side note – one of the things I also got from these books was that Kings and leadership didn’t pass down through family (ie sons) the way we seem to assume they do now. The ancient Romans would have thought that was ridiculous. How do you know kids can rule as well as their parents? That idea came along much, much later, and it was somewhat surprising to me.

I was also stunned at how interesting the whole setup of government was as the republic took shape. Very corrupt, but also very stable.

On the other hand, the discussion of political norms, and how those were slowly chipped away (in both books) hits a bit close to home at times. The political maneuvers ring true in a number of ways, and there’s a lot to make you uneasy. Still, you are much less likely to get killed while trying to vote or get elected today than you were then.

Next up was Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, by Peter Gibbons. I didn’t like it. Too dry. I tried and tried, and then decided to move on and come back later. So I moved on to The Fall of Rome: And the End of Civilization by Bryan Ward-Perkins. I was somewhat unprepared for how interesting the fall of Rome would be.

I used to think of “civilization” as meaning big buildings, big armies, and a stable government. But it’s the economic stuff I took for granted that mattered. Because roads were so good and trade was so robust, people would stop trying to specialize locally. The would get amazing pottery from far away, for instance, so why bother to make it close to home. Food moved all over, so you didn’t need to farm as much. But as the empire collapsed, so did its trade. You couldn’t get that pottery anymore. You couldn’t get cheap and easy food. The quality of life of pretty much everyone dropped dramatically, not just in how much money they had but in what you could actually obtain. People had to go back into farming or starve. I wasn’t thinking about the fall of civilization properly.

And THAT’s why I’m even more excited for March. I want to read more about that, and how people pulled themselves back up. It was also good to sit and think about how the world’s superpower that hung around for like 1000 years completely fell apart. Why? I want to know more about that and what came after. On to March.

Oh, I tried to go back to Gibbons again at the end of the month, and still couldn’t fininsh the book. I know it’s a classic. Sorry.

tl;dr: If you want to focus on history up to the fall of the republic, read Mike Duncan’s The Storm Before the Storm. Mary Beard’s SPQR, is more of a broader review of Rome from the beginning through the emperors, but also great. More Fall of Rome next month.

February 26, 2018

Help me learn new things in 2018 – The Fall of Rome/The Dark Ages (What should I read?)

I’m going to spend March learning about the Fall of Rome and the Dark Ages. You’ve already also given me some great ideas. I want to post them here, so you can help me prioritize what to read. If you think I’m missing something, please go tell me. I’m opening comments, or you can tweet me.

The Inheritance of Rome: Illuminating the Dark Ages 400-1000 (Chris Wickam)

Fall of Rome and the End of Civilization (Ward-Perkins, and I already read it this month)

The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians (Peter Heather)

How Rome Fell: Death of a Superpower (Adrian Goldsworthy)

Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed (Jared Diamond)

The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (Susan Wise Bauer)

The Fate of Rome: Climate, Disease, and the End of an Empire (Kyle Harper)

What do you all think? Any thoughts on the order? Am I missing something good?

February 22, 2018

As Idaho goes, so goes the nation.

I’ve got a new piece at Vox digging into Idaho’s decision to flout the Affordable Care Act. If you want to learn something about Idaho administrative law (I know, I know, pure clickbait), this is the place to look. I also kick the tires on the analogy between what Idaho’s doing and marijuana legalization.

The upshot is that I wouldn’t count on the courts to intervene, even though what Idaho is doing is patently illegal.

If Idaho moves forward and other states follow its lead, what will emerge is a gray market in noncompliant insurance coverage, not unlike the gray market in legalized marijuana. Indeed, the marijuana analogy fits neatly. In both cases, state officials have purported to legalize conduct banned by federal law; in both cases, federal officials have been reluctant to enforce a law they disagree with.

And as with marijuana, what starts in one state will spread. As floutings of federal law go, Idaho’s approach is pretty measured. Under its rules, insurers that sell noncompliant plans must also sell compliant plans, the unhealthy can “only” be charged 50 percent more than the healthy, and insurers must cover preexisting conditions (unless there’s a gap in coverage, in which case they don’t).

But other red states that follow Idaho’s lead may not be so restrained. They might allow insurers to ditch their ACA-compliant plans, to exclude any and all preexisting conditions, or to jettison coverage for mental health care. Red states could take us back to the harsh pre-ACA state of affairs, and all without the need for congressional action.

So this story isn’t really about Idaho. It’s about every Republican-controlled state that’s waiting to see what happens next.

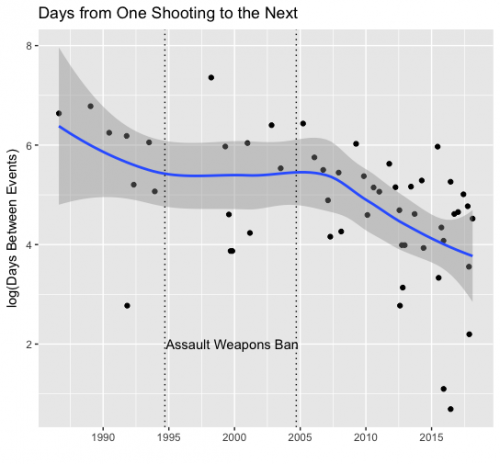

Did the Assault Weapons Ban Slow the Acceleration of Mass Shootings?

The data on mass shootings show that the frequency of these killings has been increasing. Many of the killers have used military-style rifles, including the AR-15. The use of these rifles has prompted some people to call for a renewal of the federal ban on assault weapons, which was passed by Congress on September 13, 1994, and expired on September 13, 2004.

Critics of the proposed ban argue that the definition of an ‘assault rifle’ is vague and arbitrary. There is merit in that claim, although I am not sure how much we should care if the ban saves lives anyway. To the latter point, however, critics claim that the 1994 ban had little effect.

I can’t evaluate whether the ban worked. That would require time, data sets, and expertise that I lack. But I decided to look at my data set of shootings where more than four people were killed and see if there was any evidence about the effect of the ban.*

Below is a graph of the logarithm of the days between successive massacres, as a function of their dates. I have also plotted a loess-smoothed curve to look for trends in the data. The fall in the curve means that the time between events is decreasing, which is another way of saying that the frequency of massacres is increasing. The vertical lines mark the beginning and end of the assault weapon ban.

The accelerating frequency of mass shootings appears to have slowed while the assault weapons ban was in effect.

Taking the logarithm makes the increase in frequency look less dramatic: the untransformed data are much scarier. However, because all you see in the untransformed data is the speedup in the rate of massacres, it’s hard to see anything else. What this graph shows, however, is that the frequency of mass killings was increasing before the ban started and after it ended, but that it paused while the ban was in effect. Christopher Ingraham makes a related argument here in the Washington Post.

There are so many caveats needed here. First, this is a small dataset. Massacres are, thanks be to God, uncommon events (albeit becoming more common). Second, the coincidence of a slowdown with the assault weapons ban proves nothing. These data can’t tell us whether the ban caused the slowdown; it could have been something else in that decade. Finally, the slowdown in the increase in massacres means that lives were saved. That’s good and worth doing, but what we want is for the curve to trend up.

Bottom line: I can’t tell you that the assault weapon ban worked. But it may have had a small effect.

*Thanks to friend-of-the-blog Dr. David States for the prompt to look at this.

February 21, 2018

Healthcare Triage: The Health System of Taiwan: HCT Healthcare of Many Nations

Every once in a while, we like to take a moment and focus on health systems around the world. Today, we’re looking at Taiwan, which made the transition to a single payer system kind of suddenly, and pretty recently.

This episode was adapted from a column Austin and I wrote for the Upshot.

Aaron E. Carroll's Blog

- Aaron E. Carroll's profile

- 42 followers