Phil Simon's Blog, page 53

August 9, 2016

Striking the Right Balance: The Tension between Flexibility and Security

As any old-school CIO or IT manager will tell you, it was much easier to secure the enterprise 20 years ago. Sure, there were plenty of bad actors, but employees didn’t bring an increasing array of devices to work—ones that opened the enterprise up to increased breaches. Not only are employees bringing their own devices to work, they’re bringing their own software to work.

As much as I advocate working from anywhere, it’s folly to dismiss the legitimate security concerns of letting employees work unencumbered. Think about the following polarized scenarios:

Organization A: Employees enjoy complete freedom and flexibility to do whatever they want wherever they want. Security is not an afterthought; it’s not even a consideration.

Organization B: Employees must seek formal IT approval for everything. Everything is locked down by default, encumbering basic productivity, never mind organizational agility.

Which is better?

Of course, neither is ideal. Even the most secured enterprise faces internal and external risks. It’s critical to put safeguards in place, but make no mistake: employees still need to be able to get work done without involving IT at every step along the way. (I once consulted at a consumer-goods company that made employees do just that. You couldn’t go to the bathroom without your computer locking up.)

A Happy Medium

With that in mind, here are some tips to for organizations strike the right balance. First, BYOD is here. Don’t try to fight it. A 90,000-student university is neither a small law firm nor an Alicia Keys’ concert.

With that in mind, here are some tips to for organizations strike the right balance. First, BYOD is here. Don’t try to fight it. A 90,000-student university is neither a small law firm nor an Alicia Keys’ concert.

Next, don’t skimp on employee training and communication. My new employer ASU sure isn’t. The university knows full well the security risks posed by negligent employees. Before I could collect my first paycheck, I had to complete several employee orientation courses designed to reduce the chance that I cause a security issue. And that’s not all. Employee education shouldn’t end when new employees join an organization. As such, ASU maintains a site dedicated to security threats and best practices.

Employee education shouldn’t end upon joining an organization.

On the technical side, consider the words of Tom Smith, VP of Business Development of CloudEntr. Smith notes that companies can restrict remote access to sensitive data by device-specific identifiers such as the MAC address. What’s more, consider adopting encryption and dynamic data-level authentication, a process known by the clunky name of deperimeterization.

Simon Says

One need not be a security expert to understand the increasing number and severity of bad guys out there. Organizations more than ever need to be aware of—and respond to—remarkably sophisticated attacks. At the same time, though, organizations don’t want security to become bottlenecks.

Feedback

What say you?

This post was brought to you by IBM Global Technology Services. For more content like this, visit Point B and Beyond.

This post was brought to you by IBM Global Technology Services. For more content like this, visit Point B and Beyond.

The post Striking the Right Balance: The Tension between Flexibility and Security appeared first on Phil Simon.

August 1, 2016

The Millennial Imperative: Embracing New Technologies and a New Mind-Set

By the time that you read this, I’ll be ensconced in my new position as a full-time faculty member at ASU’s W. P. Carey School of Business. In my first year, I’ll be teaching a number of courses in the Department of Information Systems, including CIS440: Systems Design. As part of the course curriculum, students need to read a number of books, one of which is The Phoenix Project: A Novel about IT, DevOps, and Helping Your Business Win (affiliate link).

At a high level, the excellent book tells the story of Parts Unlimited, a fictional retail organization in the midst of a maelstrom of technological changes and business challenges. Employees are overwhelmed, IT budgets are getting slashed, data problems are endemic, and the conflict between line-of-business employees and IT is exacerbating.

Sound familiar?

Many large organizations going Agile.

As I blew threw the novel, I couldn’t help but think about the technology and cultural differences between large, stereotypically stodgy enterprises and their nimbler, smaller counterparts. (These are often startups.) The former have historically released new applications, systems, and technical tools via the Waterfall model, often unsuccessfully as I describe inWhy New Systems Fail. For their part, the latter have embraced Agile methodologies, iterative releases, and, most recently, Lean Startup methods.

This begs the question: Which is the “best” way to deploy a new technology, release, or feature? In the abstract, there’s no right answer to that question, but it’s interesting to note that many large organizations (such as GE) going Agile.

To be sure, the Waterfall model suffers from significant limitations. For one, it typically takes longer to identify issues, never mind fix them. Nor does it typically account for changes. That is, a business need expressed in the requirements-gathering phase may have changed considerably.

Beyond these obvious drawbacks, though, there is a subtler problem with relying exclusively on top-down development, especially today. Organizations that cling to antiquated ways and technologies risk losing out on top-notch young and tech-savvy candidates. Millennials know that they almost certainly won’t work at a single organization for their entire careers. Reid Hoffman of LinkedIn even advocates that they adopt a “tour of duty” mind-set. To this end, they want to build things more than participate in meetings and conference calls. You learn more by doing than maintaining.

Simon Says

Today, companies can ape business models, strategies, and organizational capability faster than ever. Thanks to the rise of cloud computing and open-source software, technological barriers to entry have never been lower. Against this backdrop, how can an organization build a sustainable competitive advantage?

Perhaps through its people and its ability to adapt. I’m hard-pressed to think of a more significant chip than attracting and retaining the best people. To this end, it’s never been more important for large organizations to not only embrace newer technologies, but a more progressive mind-set—one that includes BYOD, true collaboration, and a work-from-anywhere mind-set.

Feedback

What say you?

This post was brought to you by IBM Global Technology Services. For more content like this, visit Point B and Beyond.

This post was brought to you by IBM Global Technology Services. For more content like this, visit Point B and Beyond.

The post The Millennial Imperative: Embracing New Technologies and a New Mind-Set appeared first on Phil Simon.

July 26, 2016

Success and Luck

For my money, Breaking Bad is the greatest show of all time. The acting, writing, cinematography, music, and message of the show are simply astonishing.

Many people don’t realize, however, that several high-profile networks passed on Vince Gilligan’s story about a high school teacher with terminal lung cancer who starts manufacturing crystal meth. What’s more, Gilligan had to fight to cast Bryan Cranston in lieu of more established names.

In subsequent interviews, both Gilligan and Cranston have exuded utter humility. They realize that, to be successful, you have to be both lucky and good. Of course, this flies in the face of much conventional thinking. Many people (wrongly) believe that they have succeeded by dint of their own toil—and nothing else.

Against this backdrop, I recently sat down with Cornell professor Robert H. Frank. We talked about his new book Success and Luck: Good Fortune and the Myth of Meritocracy (affiliate link). The following is an excerpt from our conversation. (Note that his publisher sent me a copy gratis without further obligation.)

PS: You’re lucky to even be here after what happened to you on a tennis court. Explain.

RF: I’ve been the beneficiary of chance events many times during my life, but one in particular stands out.

I was playing tennis with my longtime friend and collaborator, the Cornell psychologist Tom Gilovich, at an indoor facility on a chilly November morning in 2007. As we sat between games during the second set, Tom later told me, I complained of feeling nauseated. Moments later, he said, I fell off the bench and lay motionless on the court. When he knelt to investigate, I wasn’t breathing and had no pulse.

After yelling for someone to call 911, he flipped me onto my back and started pounding on my chest. He hadn’t been trained in CPR but, like most of us, had seen it done many times in films. After what seemed like forever, he said, he got a weak cough out of me. But then I slipped away again.

After yelling for someone to call 911, he flipped me onto my back and started pounding on my chest. He hadn’t been trained in CPR but, like most of us, had seen it done many times in films. After what seemed like forever, he said, he got a weak cough out of me. But then I slipped away again.

Moments later, a team of emergency medical technicians burst through the door of the tennis facility. They cut off my shirt, put the paddles on my chest and shocked me back to life. After being rushed to our local hospital, I was flown by helicopter to a larger hospital in Pennsylvania, where I was put on ice overnight.

Doctors told my family learned that I’d suffered an episode sudden cardiac death. They said that 98 percent of people who experience such episodes don’t survive them, and that the the few who do typically suffer serious cognitive and other impairments. And in the three days following the event, I’m told, I spoke nonstop gibberish from my hospital bed.

To be successful, you have to be both lucky and good.

But on day four, for reasons that have never been clearly explained to me, I awoke with a clear head. I was discharged the next day, and after passing a stress test shortly thereafter, I was back on the tennis court with Tom again.

Since the facility where we were playing was located well outside the city, it would normally have taken an ambulance dispatched from Ithaca more than 20 minutes to reach me. That’s well beyond the survival window for sudden cardiac death, since the brain can survive for only a limited time without oxygen.

But by a pure twist of fate, the ambulance that saved my life got there much more quickly than that. Earlier that morning, it turns out, ambulances had been dispatched to two separate auto accidents that had occurred very close to the tennis center. And since the injuries involved in one of them weren’t serious, an ambulance had been able to continue a few hundred yards further to attend to me. To call myself lucky to have survived that day is thus a gross understatement.

PS: Was that the impetus for writing the book?

RF: It’s certainly one of the reasons I began thinking more seriously about luck’s role in life. But my decision to write Success and Luck was spurred more by my gradual realization that most of us scarcely notice the extent to which our lives are shaped by external forces. Of course, chance sometimes intervenes in such dramatic ways that we can’t fail to notice, as in my experience on the tennis court, or when someone wins the lottery. But such instances are rare.

Mostly our lives are shaped by randomness in subtle ways that escape notice. Maybe you had a teacher who steered you away from trouble in the eleventh grade, or perhaps you got an early promotion because a slightly better qualified colleague had to care for an ailing parent. Every career path consists of many hundreds of small steps, and if any one of them had been different, the final destination would also have been different, often markedly so. Failure to appreciate the importance of such contingencies helps explain why so many successful people are able to insist with a straight face that they’d made it entirely on their own. As the essayist E. B. White once wrote, “Luck is not a subject you can mention in the presence of self-made men.”

Mostly our lives are shaped by randomness in subtle ways that escape notice. Maybe you had a teacher who steered you away from trouble in the eleventh grade, or perhaps you got an early promotion because a slightly better qualified colleague had to care for an ailing parent. Every career path consists of many hundreds of small steps, and if any one of them had been different, the final destination would also have been different, often markedly so. Failure to appreciate the importance of such contingencies helps explain why so many successful people are able to insist with a straight face that they’d made it entirely on their own. As the essayist E. B. White once wrote, “Luck is not a subject you can mention in the presence of self-made men.”

PS: Talk to me about the man you met in Nepal and why he resonated so much with you.

RF: That would be Birkhaman Rai, the young Bhutanese hill tribesman who worked as my cook during my time as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Nepal. To this day, he remains one of the most talented and resourceful people I’ve ever met. He could butcher a goat, repair an alarm clock, and re-thatch a roof. He could re-sole shoes. He could bargain hard with merchants without offending them.

Yet the pittance I was able to pay him was probably the high point in his lifetime earnings trajectory. I don’t know if he’s still alive, but if so he’d be well past the normal life expectancy of men in Nepal. If he’d been born in the U.S., however, he’d be looking forward to many years of continued good health, and he probably would have been prosperous, possibly even spectacularly successful.

If successful Americans considered the matter even briefly, most would recognize that their lives would have turned out very differently if, like Birkhaman Rai, they’d been born in one of the world’s poorest countries. But most never give it a moment’s thought.

PS: Why is this notion of luck so threatening to so many?

RF: We see a possible hint to the answer in the hostile reactions to two similar political speeches given in 2012, one by President Obama in Virginia, the other by Elizabeth Warren in Massachusetts. If you’ll reread the texts of those speeches, you’ll see that the essential point made in each was not controversial in any way. Both speakers merely sought to remind business owners that any successes they may have enjoyed were made possible in part by society’s investments in supportive environments. Sellers were able to ship their goods to market, for example, on roads the rest of us helped pay for. They hired workers educated at community expense, and enjoyed protection from police and firefighters paid for by tax dollars. They were able to write contracts enforced by our legal system, and so on. The clear point of both speeches was that business owners should embrace their responsibility to help pay forward in support of similar opportunities for the next generation.

But as evidenced by a veritable avalanche of outraged commentary, that’s not the message that many business owners heard. Many thought they’d been told that they didn’t really deserve the success they’d achieved, that they didn’t deserve the lofty positions they held. Both addresses quickly became known as the “you-didn’t-build-that” speeches. Yet that was clearly not the speakers’ intended message.

Some might insist they succeeded entirely on their own for strategic reasons, hoping to reinforce their claim to whatever money has come their way. And there is indeed evidence that people who deny luck’s importance also feel a stronger sense of entitlement.

Yet the denial of luck’s importance can also be view more charitably. When successful people construct the narratives of their own lives, they suffer from the same kinds of cognitive biases that we all exhibit when trying to explain events. One of the most important of these is hindsight bias, according to which observed outcomes appear far more easily predictable than they actually were. Someone trying to explain a successful business career, for example, searches her memory bank for details that are consistent with that outcome. And since most successful people are both extremely talented and hardworking, she’ll find lots of memories of all the long hours she worked and all the difficult problems she solved over the years. Those memories will form the backbone of her life story.

Whatever its cause, the tendency to deny luck’s importance has kindled tax resistance that has jeopardize our ability to maintain the kinds of environments that enabled so many of us to succeed in the first place.

PS: Generally speaking, does the view of the importance of luck hinge on one’s politics? Explain.

RF: Few questions more reliably divide liberals from conservatives than that of whether success in life depends to any significant extent on luck. As in discussions of free will, liberals tend to emphasize to the importance of external circumstances, while conservatives tend to stress the importance of individual initiative.

But the tendency to underestimate luck’s role in success is by no means confined to one end of the partisan spectrum. And citizens from both sides of the aisle have suffered from the resulting reduction in the electorate’s willingness to support the public investments that make economic success possible.

Each of the opposing views about luck clearly captures essential elements of reality. As the sociologist Duncan Watts has written:

Building a successful life requires a deep conviction that you are the author of your own destiny. Building a successful society requires an equally deep belief that no one’s destiny is their own to write. Balancing these seemingly contradictory ideas may be the most important social challenge of our time.

The encouraging news is that the taxes required to redress our investment shortfall would be much less painful than most people think. Beyond a certain income threshold, people’s ability to get what they want depends much more on their relative purchasing power than on how much they spend in absolute terms. If the most successful among us each paid a little more in tax, all mansions would be marginally smaller, all cars less expensive, all diamonds more modest, and all celebrations a bit less costly. In each case, however, the standards that define “special” would adjust accordingly. Successful people would be no less satisfied than before.

This interview originally ran on Huffington Post. Click here to read it there.

The post Success and Luck appeared first on Phil Simon.

July 25, 2016

Who’s looking for free tech and analytics expertise?

—Monique Candelaria as Lucy in “Live Free or Die”, Breaking Bad

Starting next month, I will be teaching two capstone courses at ASU. Based on my background and body of work, both the undergraduate programs in Computer Information Systems (CIS) and Business Data Analytics (BDA) are right up my alley. I’m downright psyched to get started.

These capstone courses—CIS440 and CIS450, respectively—are designed to provide seniors with valuable real-world experience. That is, they will put theory into practice. Students will apply their newfound knowledge to solve pressing business problems and answer important questions.

To this end, I’m looking for interesting projects for my new students. If you are interested in offering a meaningful project around technology and/or analytics, then keep reading.

What’s in it for potential project sponsors?

I see quite a few benefits for sponsors. For one, these projects let them tap into the minds of eager, knowledgeable students. What’s more, sponsors can acquaint themselves with potential future hires. (Why not date before getting married, right?) Finally, these capstone projects represent a way to give back to the ASU community.

And did I mention that it’s free?

Details and Logistics

Although there’s no monetary cost, it is important that all sponsors take these commitments and projects seriously. This means devoting the requisite time to students. Answer their questions. Provide guidance where needed. Expect regular interactions; this is no “set-it-and-forget-it” type of project. Finally, sponsors will need to complete questionnaires at the end of the semester. That data will help me grade my students.

Capstone courses aren’t new at ASU and the W. P. Carey School. Prior organizations who have worked with ASU in this capacity include:

New and established startups

Small, medium, and large companies

Even a lone founder with nothing more than wireframes of his intended app

Here’s a table with some examples:

Specific Projects and Process

Past projects have run the gamut. On the technology (CIS) side, previous students have developed new web applications and apps. They have also enhanced organizations’ existing tech offerings. On the analytics side, students demonstrate their emerging data chops. To this end, prior classes and groups have looked at a wide variety of problems for professional private and public institutions—even a few sports teams. Students have provided clarity, insights, and recommendations for making better business decisions. Make no mistake: these are exactly the types of things that Big Data and analytics are supposed to yield.

Here are some additional details:

Students will work in teams of four to six over a 15-week period.

They will use the knowledge that they’ve gained during their undergraduate studies

They will learn new tools to complete their projects.

Sponsors must provide students with timely and constructive feedback.

In keeping with Agile methods, throughout the semester, students present several working demos of their work as it emerges. That is, you and I will see project progress well before final student presentations in December. To this end, sponsors must provide students with timely and constructive feedback. If you’re unwilling or unable to do this, then it’s not a good fit.

Historically, the most successful projects have been of the greenfield variety. As I know all too well, enhancements and extensions to existing projects can be challenging. Even the brightest students—and seasoned professionals for that matter—typically face significant learning curves when dealing with mature apps and methodologies. It’s nearly impossible to “hit the ground running.”

Next Steps

If you’re interested, click here to learn more about the formal application process or connect with me.

The post Who’s looking for free tech and analytics expertise? appeared first on Phil Simon.

July 12, 2016

Chart Design for Mobile Devices Made Simple

If you’re of a certain age, then you remember how easy it was to build and design charts and graphs that users could view on screens. The design and deployment process was simple because the vast majority of users viewed them on proper computers, most likely running one of a few versions of Microsoft Windows.

My how times changed.

Today, properly displaying visual information on screens is anything but simple. This stems from the explosion of mobiles devices and operating systems. And if you think that there’s only “one” version of Android, think again. (Interestingly, Microsoft has admitted its irrelevance on smartphones and tablets.)

Charts on Mobile Devices

Brass tacks: For a number of reasons and in no particular order, properly displaying charts and graphs is often challenging:

There’s just less real estate (read: screen size) to work with.

Zooming in and out on data often zooms in on the whole chart—not the data within the chart. (This can result in user frustration and broken screens.)

Fitting large titles and many labels in a small number of pixels can be difficult if not impossible.

Scrolling issues can be maddening. Sometimes a chart can prevents users from scrolling past it on the page.

Since one size often doesn’t fit all, it requires a great deal of effort to make one chart for desktops, one for mobile devices, and one for print.

What’s the end result from all of these usability issues? Oh, not much. Only frustrated employees and customers, irate calls to IT departments and developers, squandered opportunities, and generally poor business decisions.

Bad dataviz never helped anyone.

The begs the question, What to do?

Fortunately, there’s a nifty solution. ZingChart has just released a mobile-chart plugin for its JavaScript charting library. The robust package supports a wide variety of charts, including bar, line, area, scatter, bubble, pie, and ring. Here’s an example:

See the Pen ZingTouch | Pinch&Expand by ZingChart (@zingchart) on CodePen.

Note that you will only see the features if you’re viewing this post on a phone or a tablet.

Feedback

What say you?

This post is brought to you by ZingChart’s JavaScript charting library. The opinions expressed here are my own. The ZingChart folks love charts. Feel free to hit them up for your dataviz project.

This post is brought to you by ZingChart’s JavaScript charting library. The opinions expressed here are my own. The ZingChart folks love charts. Feel free to hit them up for your dataviz project.

The post Chart Design for Mobile Devices Made Simple appeared first on Phil Simon.

July 11, 2016

The Case for Multiple Clouds

I’ll be the first to admit that I have always been a bit persnickety when it comes to language, especially in the technology world. In fact, I penned Message Not Received in part as a form of linguistic catharsis. In my defense, I’m hardly the first person to realize that writing costs much less than than therapy.

That book details how the tsunami of business jargon is overwhelming folks at work. Neologisms, forced portmanteaus, backcronyms, and new buzzwords permeate the business landscape these days, but it gets even worse: Many people struggle trying to discern what even ostensibly simple and commonly “understood” tech terms actually mean.

Case in point: “the cloud.” As I’ve said many times, there is single “cloud” any more than there is one app or database.

Welcome to the Multi-Cloud World

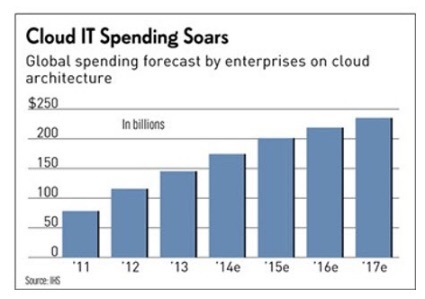

There are many reasons for the emergence of a multi-cloud world. For starters, it’s no overstatement to say that cloud computing is exploding. What was once by all accounts a niche market may approach $256 billion by 2018. Predictably, prices have dropped considerably as well. The result is a virtuous cycle that has fueled increased adoption.

There are many reasons for the emergence of a multi-cloud world. For starters, it’s no overstatement to say that cloud computing is exploding. What was once by all accounts a niche market may approach $256 billion by 2018. Predictably, prices have dropped considerably as well. The result is a virtuous cycle that has fueled increased adoption.

Along these lines, cloud computing has matured considerably in the last six years. In the process, it has converted some early high-profile skeptics. Exhibit A: Oracle executive chairman and CTO Larry Ellison. As Brandon Butler writes on NetworkWorld:

As recently as 2009, Ellison was one of the industry’s biggest cloud-bashers, questioning what the cloud really was, accusing venture investors of latching on to the latest fad and dismissing the cloud the hot fashionable buzzword of the day. But since then Ellison’s views on the cloud seem to have evolved.

“Evolved” is putting it mildly, but there are more reasons that the idea of multiclouds has gained considerable traction as of late.

There is no single “cloud” any more than there is one app or database.

Given the wide variety and types of clouds available, organizations can go shopping and match the right clouds to their business needs. That is, more than ever, one size need not fit all. As Bob O’Donnell writes on Recode, “Some of the more interesting developments in server design are coming from the addition of new chips that serve as accelerators for specific kinds of workloads.”

For instance, highly sensitive customer or patient data often serve as the greatest source of hacker interest. This may well require organizations to enhance their security, often at greater cost. (Of course, other security threats may require different approaches and safeguards.)

Next up, remember that cloud computing is a means to an end—and that end is usually some type of business or consumer application. Fortunately, there’s never been greater portability with respect to deploying and migrating these applications. Thanks to tools such as Docker (a new IBM partner), organizations of all sizes can switch clouds and vendors faster and easier than ever. This is dramatically different than things a decade ago. As I know all too well, fear of system failure and operational issues have led many CXOs to delay the deployment of key business applications and maintain antiquated ones.

Simon Says

Don’t get me wrong. I can’t advocate an organization using 25 different clouds from 24 different vendors. Complexity can still hamstring an organization and engender massive data issues. Still, no longer do companies need to limit themselves to a single cloud or vendor.

Feedback

What say you?

This post was brought to you by IBM Global Technology Services. For more content like this, visit Point B and Beyond.

This post was brought to you by IBM Global Technology Services. For more content like this, visit Point B and Beyond.

The post The Case for Multiple Clouds appeared first on Phil Simon.

July 7, 2016

Can the IoT prevent the next Flint?

Photo credit: LA Times

Twenty years ago back in grad school, I remember watching Roger & Me, Michael Moore’s moving 1989 American documentary about Flint, MI and the decline of the American auto industry. When I think about how much has changed in that time, my head nearly explodes.

I often reflect that, in the years since the Internet—and technology in general—have exploded. In the process, some people have benefited immensely. Silicon Valley has certainly anointed New Kings, to borrow a phrase from the just-released Marillion song. To be sure, though, many others have been left behind. And, if you’ve been paying attention to the news over the past year, Flint residents have had salt poured in their wounds in the form of a terrible water crisis.

Here’s a timeline and infographic of what happened and when:

Stories such as these justifiably provoke anger, sadness, calls for the resignations of public officials, and even lawsuits. (For more on this, see The Social Determinants of America’s Lead Crisis.)

Fixing Flint’s water supply will be neither quick nor cheap, but the larger question is, How can we prevent the next disaster? While there may be no simple answers, perhaps part of the solution lies in technology.

Enter the Internet of Things

The IoT is coming and we can only begin to imagine how it can benefit humanity.

Specifically, what if there were a way to automatically monitor water supplies for levels of lead, and other toxic materials and pollutants? I’m not just talking about sending inspectors to conduct manual tests at regular intervals. I’m talking about instantly gathering data to alert public officials and regulatory agencies the moment that something untoward is taking place.

Sound like a pipe dream? It turns out that powerful and inexpensive sensors can analyze and instantly report on just this very thing, but don’t believe me. Consider the following:

Exhibit A: Sensors are helping farmers increase their crop yields. As Libelium has discovered, there’s no reason that the same sensor fundamental technology cannot work with water supplies.

Exhibit B: The city of Boston is quickly identifying and fixing potholes thanks to a smartphone app launched in July 2012. StreetBump runs in the background and requires nothing more than a download.

Uses such as these fall under the much-hyped umbrella of the Internet of Things (IoT). I’ll be the first to admit that we’re not there yet. What’s more, today formidable impediments remain to achieving this dream—specifically, the adoption of common, industry-wide standards. Make no mistake, though: the IoT is coming and we can only begin to imagine how it can benefit humanity.

Simon Says

We’re clearly in the first inning, but one thing is certain: Expect more examples such as these in the near future. The IoT will generate valuable, real-time data that not only can make for better, more efficient government. Moreover, it will reduce the odds that calamities such as Flint take place.

Feedback

What say you?

Originally published on HuffPo. Click here to read it there.

The post Can the IoT prevent the next Flint? appeared first on Phil Simon.

July 5, 2016

Uber, AirBNB, and the Adjacent Possible

Back in 2009, Garrett Camp and Travis Kalanick founded what was then a little ride-hailing company called Uber. Odds are, though, that you’ve only heard of it only relatively recently. The company that bills itself as “everyone’s private driver” to date has raised a mind-boggling $15 billion.

As shown below, the vast majority of that sum has come in the last two years. (Ditto for the controversies surrounding the company, but that’s a post for another day.)

Source: Crunchbase

It turns out, though, that the idea of Uber isn’t so new after all. In fact, as Ezra Klein points out on Vox, venture capitalists had heard the idea for Uber way back in 2005. From the piece:

Chris Dixon, a venture capitalist at Andreessen Horowitz, has a useful framework for thinking about this argument. ‘In 2005, a bunch of companies pitched me the idea for Uber,’ he says. ‘But because they followed orthodox thinking, they figured they would build the software but let other people manage the cars.’

This begs the question: In an age of rapid disruption and change, why did it take mass ride sharing—and Uber in particular—so long to jump from theory to practice?

Explaining the Rise of Uber and its Ilk

The short and general answer is that Uber back in 2005 only existed in what Steven Johnson calls the adjacent possible. For instance, the great Charles Babbage essentially conceived of the modern-day computer nearly 150 years ago, long before the technology existed to build it.

The longer, more nuanced answer is that the rise of cloud computing, smartphones, Big Data and apps made Uber possible. If you’re Camp, Kalanick, or an early Uber investor, you couldn’t be more pleased. However, if you work for a conventional taxi company, you most certainly find Uber, Lyft, and their ilk very disruptive—and you should. Aside from Uber’s myriad legislative battles and even fines, some driver protests have turned violent.

Without cloud computing, smartphones, and apps, Uber and AirBNB don’t exist.

If Uber’s keeping you up at nights, at least you’re not alone in your consternation. Traditional hotel chains aren’t too fond of AirBNB, a company with both similarly outsize ambitions and a questionable record with respect to abiding by current housing statutes. And don’t get me started on the company’s misplaced PR efforts.

I could go on but you get my point: never before has disruption come so quickly and from such unpredictable sources. Case in point: Who would have thought even three years ago that an iconic search engine would be building driverless cars?

Simon Says

Clamor all you want for the now-quaint days of the 1980s, but rapid disruption is here to stay. Sure, there are downsides, but make no mistake: these same powerful technologies that have upended major industries concurrently provide enormous opportunity. (For more on this, see the IBM report “Analytics: The upside of disruption.”)

Feedback

What say you?

This post was brought to you by IBM Global Technology Services. For more content like this, visit Point B and Beyond.

This post was brought to you by IBM Global Technology Services. For more content like this, visit Point B and Beyond.

The post Uber, AirBNB, and the Adjacent Possible appeared first on Phil Simon.

June 27, 2016

Unplugging at Work: My Interview with Vicki Salemi

If you feel the constant pull of electronic leashes at work, you’re not alone. It turns out that many people are in the same boat while on the clock—and even off it it.

I recently sat down with consultant and columnist Vicki Salemi to discuss that topic. A very brief excerpt of our interview ran on the New York Post. Here’s the entire conversation.

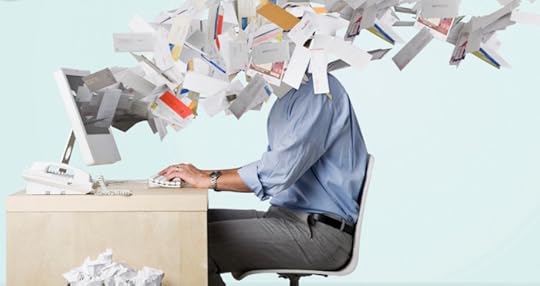

VS: Get this, a study from 2015 said that the average US worker spends 6.3 hours a day on e-mail. What are your thoughts on that? And what does it say about us in terms of productivity and a society (workaholics, anyone)?

PS: That number seems high to me and contradicts the research that I did for the book. In July 2012, the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI) released a report titled “The Social Economy: Unlocking Value and Productivity Through Social Technologies.” MGI found that knowledge workers on average now spend fully 28 percent of their work time managing e-mail.

Regardless of the actual number, though, it’s hard to dispute the assertion that we spend more time than ever on e-mail. On average, we receive 120 to 150 e-mails per day—and that number is increasing at a rate of 15 percent per year. (Source: the Radicati Group.) Because of smartphones, it’s never been easier to check our messages while waiting for coffee, on line at the supermarket, or even while in the bathroom. It’s completely out of control.

VS: Is it OK not to check e-mail on weekends and days off?

PS: In short, yes. All communication is contextual and personal. In Message Not Received: Why Business Communication Is Broken and How to Fix It, I stop short of issuing edicts such as these. You have to do what works for you. Understand, though, that every time you read and respond to a late-night or weekend message, you’re implicitly saying that this is acceptable.

Many organizations are starting to discourage or even ban off-hours e-mails. They realize that this constant frenzy of messages is causing employee burnout.

VS: Are we totally abusing and overusing e-mail? How so?

PS: Yes. We often prefer e-mail because it’s asynchronous. That’s just a fancy way for saying that we can respond to a message when it’s convenient for us. Both parties don’t need to be using it concurrently for it to work.

We also often opt for it in lieu of personal conversations. Sending a file or link via e-mail is fine. Far too many people, however, use it to conduct “conversations.” In the process, they invite misunderstandings and arguments. Consider a 2006 series of studies by two psychologists, Justin Kruger, PhD of New York University and Nicholas Epley of the University of Chicago. They demonstrated that text-based communication only works about 56 percent of the time.

VS: Should you put an “out of the office” (OOO) message on for the weekend if you know you won’t check your e-mail?

PS: Yes, but you have to do more; you have to stick to it. A Google programmer recently took a much more radical—and, I would argue, more effective—approach. He set his “out of office” message to read: “I’m deleting all of my e-mails when I return on [insert date]. If your message is really important, send it again after I return.”

You can always express your desire to unplug from work. There’s a ton of research that cites the benefits of doing just that.

VS: What if your boss expects you to be available at all times? Do you just have to deal with it?

PS: Great question and I address that at the end of the book. The short answer is no, especially in the long term. You can always express your desire to unplug from work. There’s a ton of research that cites the benefits of doing just that.

If your manager refuses to respect your limits, you can always look for another position somewhere else. Nowhere is it written that you have to be available 24/7. More and more workplaces are recognizing the drawbacks of these types of pressure-packed environments.

VS: What are the negative effects of constantly checking e-mail? For instance, greater anxiety and stress, plummeted productivity, etc.

PS: Constantly checking e-mail (or texts, Facebook, etc.) inhibits productivity. Put differently, this is what Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi calls flow or a state of “optimal experience” in his eponymous book Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. To do your best work, you need uninterrupted time, not two minutes here and there.

Checking e-mail on vacation prevents us from unplugging and recharging our batteries. Many workers can’t stomach returning to work after a weeks’ vacation with 700 unread messages—with more coming all the time. As a result, their vacations aren’t really vacations at all. This is simply unhealthy.

Checking e-mail on vacation prevents us from unplugging and recharging our batteries. Many workers can’t stomach returning to work after a weeks’ vacation with 700 unread messages—with more coming all the time. As a result, their vacations aren’t really vacations at all. This is simply unhealthy.

Beyond that, e-mail induces stress—and not just among American workers. LexisNexis in 2010, the company conducted its second International Workplace Productivity Survey. Its findings confirmed what many have long suspected: e-mail is very distracting.

More than eight in ten (85 percent) white-collar workers in Australia and more than two-thirds (69 percent) of South Africa’s professionals say the constant flow of e-mail and other information is distracting, making it more difficult to focus on the task at hand. Six in ten workers in the U.S. (60 percent), U.K. (62 percent), and China (57 percent) echo this sentiment.

E-mail also gives the sender the appearance that all messages have been received when, in fact, nothing can be further from the truth. (This is one of the reasons that I titled the book Message Not Received.) From the same LexisNexis survey, a large majority of workers in every market admit deleting or discarding work information without fully reading it. Nine out of ten (91 percent) U.S. professionals say they have done this, as have eight in ten workers in China (84 percent) and Australia (82 percent), and almost three-quarters of professionals in the U.K. (73 percent) and South Africa (71 percent).

Originally run on Huffington Post. Click here to read it there.

The post Unplugging at Work: My Interview with Vicki Salemi appeared first on Phil Simon.

June 23, 2016

On Databases, Tattoos, and Teaching Philosophies

Building a database is like getting tattooed. You really want it to be correct the first time you do it. Changes are possible but they are painful. And, like tattooing, some changes are easier than others. Adding something extra is easier than trying to change something that has been in place for a couple of years.

Among the courses I’ll be teaching in my first year at the W. P. Carey School at ASU is “CIS 440: Systems Design and Electronic Commerce.” The course focuses on the design of organizational and electronic commerce systems. It also touches on the use of project management, systems analysis, and design tools. (I’ll also be teaching courses on business intelligence and enterprise analytics in the fall.)

Bringing My Personality to the Classroom

As I think about how I’ll present each course’s material, I know that there’s a fair degree of existing structure. Still, lectures aren’t scripted. Why leave my personality at the door? I’ll have plenty of time to be professional while infusing Rush, Marillion, and Breaking Bad references into my lectures—and for good reason. The most recent thinking and research on education reveals that professors who bring genuine enthusiasm into the classroom generally do better than those who mail it in.

Quotes such as the one above make me think and laugh—never a bad combination.

Quotes such as the one above make me think and laugh—never a bad combination. I’ve seen throughout my career that, as Craig Bruce has said, “Temporary solutions often become permanent problems.”

I could be wrong, but updating or complementing well-trodden maxims with colorful analogies may lengthen students’ ever-shortening attention spans.

My friend inspired this post.

The post On Databases, Tattoos, and Teaching Philosophies appeared first on Phil Simon.