Phil Simon's Blog, page 43

February 11, 2019

Finding Teachable Moments in Survey Courses

I’ve learned over the last six months about the challenges associated with teaching ambitious survey courses. Introduction to Information Systems certainly qualifies. In short, professors cover a great deal of material at a rapid pace. As a result, we don’t spend a great deal of time on any given topic.1 In other words, survey courses by definition trade depth for breadth—a tension that’s not always easy for professors to navigate.

The breadth-depth tension is not always easy for professors to navigate.

Here’s an example. Last week, I covered the highlights of both security and ethics—both of which warrant longer discussions in different courses. In a few hours, I’ll give three largely similar 50-minute lectures on privacy to a group of mostly college sophomores. We’ll soon shift to relational databases and Structured Query Language. After the break, we’ll move to Python. (Yeah, we’re not lacking for content.)

What’s changed since last time?

I reviewed the slides from last semester’s privacy lecture. To be sure, the slide deck still holds up as is. For instance, Google and Facebook still know a frightening amount about many things. That certainly hasn’t changed.

Nevertheless, ours is not a stagnant world. A few days before every class, I ask myself what new material I can incorporate into the upcoming lecture that will resonate with students. I can’t imagine not thinking this way. Self-improvement and staying current are core tenets of my teaching philosophy.

Nevertheless, ours is not a stagnant world. A few days before every class, I ask myself what new material I can incorporate into the upcoming lecture that will resonate with students. I can’t imagine not thinking this way. Self-improvement and staying current are core tenets of my teaching philosophy.

In this case, I didn’t have to think for a very long time. AMI’s attempt to blackmail Jeff Bezos is front and center. What other story stitches together security, privacy, and ethics in a contemporary way? I’m hard-pressed to think of one. The story is the very definition of a teachable moment.

I’ll open the class with a few minutes from this video:

I suspect that I’ll see a few light bulbs over my students’ heads this morning.

Simon Says

To be sure, the prior privacy lecture still works without Bezos’ letter and its fallout. If I were a student, though, I’d want my professors to integrate current events into their classes as much as possible.

Feedback

What say you?

The post Finding Teachable Moments in Survey Courses appeared first on Phil Simon.

February 4, 2019

Celebrating the 10th Anniversary of the Publication of Why New Systems Fail

Original Version

On February 4, 2009, I released Why New Systems Fail. My first foray into long-form publishing started with a whimper, not a bang. For five long months, very little happened around the book despite my promotional efforts and those of my pricey PR firm at the time.

To be fair, a book recommending ways to avoid failures on new system implementations from a relatively unknown independent consultant couldn’t have come at a worse time. It’s not like I had established myself as a reputable author in years past. What’s more, the US was in the midst of its worst economic climate since the Great Depression. IT budgets were shrinking, not expanding.

Brass tacks: I learned the hard way that, for oodles of reasons, selling books is exceptionally difficult.1 Put differently, writing is easy. Marketing is hard.

Still, I kept at it. I’m stubborn.

Crickets No More

Second Edition

Finally, things picked up on July 15, 2009. A copy of my book had found its way to Bruce Webster. He was a fan. His subsequent review on the über-popular site Slashdot catapulted Why New Systems Fail to number ninety-freaking-one on the Amazon bestseller list. Not #91 for technology books. I mean #91—as in of all books sold on Amazon at that point.2 More than 600 people bought it that week—far more than all sales from the previous five months combined.

That didn’t suck. I often joke, though, that this was akin to Ten—Pearl Jam’s first album. I had nowhere to go but down.

In the time since, I penned an updated version of Why New Systems Fail3 as well as seven other texts. Those books have opened up many opportunities for me—most of which I did not see coming. Some of my income is even passive.

What Has Changed

Agile software-development methods such as Scrum have become far more prominent although Google Trends shows a decidedly mixed trajectory.

Despite many advances and changes, ERP failure is alive and well.

New entrants in enterprise software typically rely upon cloud computing and its cousin SaaS.4 Unlike 2009, it’s no longer weird to suggest an off-premise computing solution.

On a personal level, I like to think that I am a far better writer than I was a decade ago. The first edition of Why New Systems Fail certainly wasn’t awful, but that book would flow much better if I sat down to write it today. If I’ve learned anything over the last decade, it is that writing is very much a skill; one must hone it to improve. This involves looking both inward and outward. With regard to the latter, the scribes behind 538, Without Bullshit, and No Mercy / No Malice have profoundly affected how I tackle the craft of writing.

What Has Not

Despite many technological advances and new alternatives, ERP failure is alive and well. I’ve had many conversations with folks since the book’s publication about problems plaguing organizations as they attempt to adopt new technologies. Sure, occasionally the issues are technical in nature. More often than not, though, they’re people-related. I suspect that this won’t change anytime soon.

As for book sales, I can say this much: They’ve become easier over time but they are certainly not easy. Foolish is the soul who believes otherwise. The publishing landscape is more crowded than ever. Building a strong personal brand has helped, but make no mistake: there’s no easy way to move a bunch of books. It seems to resemble the world of startups. You learn a little more each time but success is anything but guaranteed.

Simon Says

I doubt that I’ll continue to churn out books at such a rapid pace over the next decade. I’m not lacking for ideas but teaching, speaking, and consulting take up a decent chunk of my professional time and energy.

Here’s to the next ten years of writing.

Feedback

What say you?

The post Celebrating the 10th Anniversary of the Publication of Why New Systems Fail appeared first on Phil Simon.

January 27, 2019

Audiobook of Too Big to Ignore Now Available

My 2013 book Too Big to Ignore is now available as an unabridged audiobook. In a nutshell, it outlines the contours of Big Data and, as its subtitle suggests, makes the business case for it.

My 2013 book Too Big to Ignore is now available as an unabridged audiobook. In a nutshell, it outlines the contours of Big Data and, as its subtitle suggests, makes the business case for it.

A Few Reflections on Book #5

No, Too Big to Ignore wasn’t a bestseller but it did earn out fairly quickly.1 I suspect that that’s because it arrived early to the Big-Data party. What’s more, although many of the technologies that I discuss in the book have improved over the past five-plus years, Too Big to Ignore holds up reasonably well. Readers tell me that they enjoy the text’s case studies in particular.

Five years after its publication, the book holds up reasonably well.

Too Big to Ignore was my first book to be translated into foreign languages. Although I can’t understand a word of either, I do own both the Korean and Chinese versions. Finally, more than any of my others, this book struck a chord with academics.

In the five-minute sample of the audiobook below I discuss the genius of both Oakland Athletics’ GM Billy Beane and an innovative high-school football coach.

Finally

To buy the book, click here.

To buy the book, click here.

This is my third book that Wiley has offered in this format. It joins Message Not Received and Analytics: The Agile Way. With a hat tip to Dave Grohl and Rush, I’m glad that this has finally happened.

The post Audiobook of Too Big to Ignore Now Available appeared first on Phil Simon.

January 25, 2019

Carnegie Mellon Alumni Interview

Since graduating from Carnegie Mellon in December of 1993, I have remained involved at my alma mater. For instance, the alumni newsletter interviewed me about Big Data in February of 2013. The next year, I spoke at CMU’s Silicon Valley campus about The Visual Organization, my book on data visualization. I hosted a webinar for the CMU Alumni Association in 2015 on why business communication typically fails. Finally, I’ve interviewed dozens of aspiring Tartans as a member of the Carnegie Mellon Admissions Council (CMAC).

Since graduating from Carnegie Mellon in December of 1993, I have remained involved at my alma mater. For instance, the alumni newsletter interviewed me about Big Data in February of 2013. The next year, I spoke at CMU’s Silicon Valley campus about The Visual Organization, my book on data visualization. I hosted a webinar for the CMU Alumni Association in 2015 on why business communication typically fails. Finally, I’ve interviewed dozens of aspiring Tartans as a member of the Carnegie Mellon Admissions Council (CMAC).

I recently sat down with Stefanie Johndrow of CMU’s Dietrich College of Humanities and Social Sciences. Among other things, we discuss how Carnegie Mellon prepared me for the real world, how to change careers, my favorite professors, and the interdisciplinary nature of higher education. We also expand upon some of the points that I made in a recent post.

Read the whole interview here.

The post Carnegie Mellon Alumni Interview appeared first on Phil Simon.

January 13, 2019

Why All College Students Need to Know the Basics of Coding

Last semester, I taught Introduction to Information Systems – Honors for the first time. CIS236 students typically major in finance, accounting, supply chain, entrepreneurship, and marketing. Put differently, they don’t study information systems, let along programming. As such, plenty of students asked me throughout the semester why they needed to learn the rudiments of Python and Structured Query Language.

Last semester, I taught Introduction to Information Systems – Honors for the first time. CIS236 students typically major in finance, accounting, supply chain, entrepreneurship, and marketing. Put differently, they don’t study information systems, let along programming. As such, plenty of students asked me throughout the semester why they needed to learn the rudiments of Python and Structured Query Language.

Below are my most common responses.

Software Is Eating the World…and No One Is Immune

I quote Marc Andreessen within fifteen minutes of the first class. Uber and Airbnb represent excellent cases in point. Think that software and technology are not changing traditionally non-technical fields, industries, and job functions? Think again.

Consider a more recent example. Just look at what Netflix Black Mirror showrunner Charlie Brooker did when creating “Bandersnatch”1:

The biggest feat, however, was figuring out the workflow2 that would bring Brooker’s idea to the screen. What Brooker quickly realized when he sat down to write the treatment was that the nonlinear script had to be clickable, and there was no perfect tool to help him create his interactive story map. Brooker first used a program called Twine to write the outline. He even learned a new coding language. 3But as the story got more complicated, the script would glitch and inevitably crash.

Yes, even non-techies such as movie makers may need to roll up their sleeves and code at some point—a trend that will doubtless intensify in the future.

Facility with Coding Differentiates Employees and Job Applicants

Consider two students: Alex and Geddy. The longtime friends attended comparable universities. They each studied supply chain and did well. The only difference: Geddy noodled with SQL when he was a student while Alex did not.

Both interview at Company ABC for the position of supply-chain analyst. Alex and Geddy assume that they have the same chance of landing the job but they lack a key piece of information.

Both interview at Company ABC for the position of supply-chain analyst. Alex and Geddy assume that they have the same chance of landing the job but they lack a key piece of information.

ABC has experienced intermittent issues with the supply-chain module of its ERP system. No, it’s not a Hershey’s-type debacle. Still, for some reason, product and supplier data occasionally becomes compromised, typically requiring ABC employees to submit urgent help-desk requests. Ultimately, IT attempts to right the ship by working with supply-chain personnel but the IT-business divide complicates matters. A more tech-savvy analyst would be able to fix things much faster than the status quo.

For this reason, ABC extends an offer to Geddy, not Alex. (Sorry Lerxst!)

Careers Are More Ephemeral than Ever

Students who obtain their degrees in marketing may well start their careers in that field, but will those 22-year-olds stay there? A LinkedIn study found that Millennials can expect to change jobs four times by the age of 32. Given the increasing rate at which we are adopting new technologies, aren’t graduates who possess a modicum of coding experience at an advantage over their less technical brethren? At a bare minimum, don’t the former have more options than the latter?

Confidence in Learning New Tools

At some point sooner rather than later, every college graduate will need to learn a new software application, productivity tool, or programming language. Students who already possess a little coding knowledge and experience should be able to connect those new dots easier. I doubt that they’ll feel as intimidated as their tech-challenged counterparts.

Respect from Proper Software Engineers

If I learned anything from my days implementing enterprise systems, far too often folks in HR or marketing don’t know what they don’t know. As I result, they’ll often create business requirements in a vacuum—typically a Microsoft Word document. They then in turn just expect developers to magically make it happen. This rankles IT folks to no end.

Respect from developers and IT folks in general can pay dividends down the road.

Generic marketing graduates certainly don’t know the technical ins and outs of Salesforce.com—today’s most popular CRM system. Still, those with at least a perfunctory understanding of contemporary programming concepts probably won’t assume that all application and database changes are easy ones. As I know from personal experience, respect from developers and IT folks in general can pay dividends down the road. It’s hard to overstate the importance of credibility in an organization—especially for newly hired college grads.

Simon Says: Coding matters for all college graduates today, not just with technical majors.

Sure, programming languages come and go, but many core concepts remain fairly constant. Coding is much like data: This isn’t 1985. Being oblivious to its existence and importance is a recipe for obsolescence or professional disaster.

Feedback

What say you?

The post Why All College Students Need to Know the Basics of Coding appeared first on Phil Simon.

January 11, 2019

What College Professors Can Learn from Hasan Minhaj’s Patriot Act

Upon a friend’s recommendation, I recently checked out Hasan Minhaj’s new Netflix show Patriot Act. In a word, it’s excellent. The Daily Show alumnus fuses political satire, scathing commentary, humor, and interactive data visualizations in a way that his counterparts just don’t.

Upon a friend’s recommendation, I recently checked out Hasan Minhaj’s new Netflix show Patriot Act. In a word, it’s excellent. The Daily Show alumnus fuses political satire, scathing commentary, humor, and interactive data visualizations in a way that his counterparts just don’t.

After bingeing the seven-episode series, I started thinking about lessons that he offers to college professors. It turns out that there are quite a few.

He Educates

Patriot Act doesn’t just rant against a problem or an injustice every episode. The show routinely informs its viewers and, I’d argue, makes us smarter.

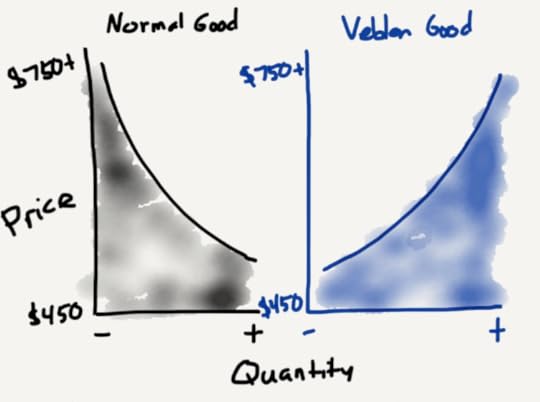

Case in point: A core tenet of economics is that demand for all but a few products drops as price increases. Not so with Veblen goods. I learned quite a bit while attending Carnegie Mellon but that concept escapes me.

Case in point: A core tenet of economics is that demand for all but a few products drops as price increases. Not so with Veblen goods. I learned quite a bit while attending Carnegie Mellon but that concept escapes me.

No bother. Minhaj reminded me of that oddity in his show on the iconic streetwear brand Supreme brand. I’d bet that few economics professors would introduce potentially boring subjects such as these in as contemporary or interesting a way.

He Supports His Assertions with Cold, Hard Data and Compelling Data Visualizations

You may not agree with Minhaj’s politics but the way that he builds his case throughout the show is worth exploring. Minhaj buttresses his arguments with plenty of supporting evidence. Sure, he uses anecdotes but doesn’t shy away from data and interactive data visualizations.1 The one below on an underreported but terrifying oil spill is particularly effective.

He Engages His Audience

Watch five minutes of Patriot Act and it’s nearly impossible not to get hooked. Minhaj frequently moves around on the set and his enthusiasm is downright infectious; viewers can’t wait to see where he’s going next. I wonder how many students would say the same about monotone instructors who remain tied to their lecterns reading off of prosaic slides?

He Tells a Story

Over the course of 18 to 25 minutes, Patriot Act takes its viewers on a journey. Most shows consist of a single subject with a carefully constructed arc. In this vein, the show resembles Last Week Tonight.

Professors don’t put on shows per se. We are not entertainers. Still, isn’t a class fundamentally an opportunity to tell a story with a beginning, middle, and end? I’d argue that the answer is yes. We should think about the content that we’re presenting, the order in which we’re presenting it, and the point of each argument, fact, chart, and the like.

He Entertains

Minhaj is a professional comedian, something that few professors can claim. That doesn’t mean, though, that we can’t inject humorous moments into the classroom from time to time.

Self-deprecation can be a good thing.

On a similar level, Minhaj isn’t afraid of taking shots at himself. At one point, he shows a dated, awkward picture of him and his then-girlfriend. That reminded me of a time-machine in-class exercise in which I took students back to 1997. I had them guess the most popular movies and tech companies of the era. I also showed them a picture of yours truly sporting a funky haircut, 90s classes, and a double-breasted suit to boot. The students got a kick out of it.

Brass tacks: Self-deprecation can be a good thing.

Patriot Act Makes Viewers Think Critically about Trends and Current Events

Arguably the most important thing that professors need to impart to their students these days is critical thinking. Lazily looking something up on the Internet hardly suffices for knowledge. More than ever, it’s essential to question companies’ claims about their roles in society. I may show future classes the show’s segments on Amazon and Facebook. These companies’ recent actions often belie their claims.

Simon Says: Learn from Hasan Minhaj.

To be fair, Minhaj doubtless sports a team of über-creative folks that make his ideas, jokes, and stories pop. For their part, professors typically have to give 20 to 30 lectures each semester. We simply don’t have the time and, quite frankly, the design chops to dazzle our audiences with slick graphics and interactive data visualizations.

Still, shouldn’t we aspire to be as dynamic and informative as possible? Shouldn’t we ditch or at least minimize boring lectures that often don’t resonate with students anyway? At a bare minimum, shouldn’t we at least spice up our slides to increase student engagement?

Check out the show’s trailer here:

Feedback

What say you?

The post What College Professors Can Learn from Hasan Minhaj’s Patriot Act appeared first on Phil Simon.

December 26, 2018

Teaching Highlights from 2018

I’ve been in a particularly contemplative mood as of late. Thank the winter break. Over the last few weeks, I’ve thought about what I’ve accomplished so far in my teaching career and what remains. Today, I’ll write about the two biggest highlights of this past year.

I’ve been in a particularly contemplative mood as of late. Thank the winter break. Over the last few weeks, I’ve thought about what I’ve accomplished so far in my teaching career and what remains. Today, I’ll write about the two biggest highlights of this past year.

A Belated Thank-You

In my analytics capstone course, students are seniors and I let them select their own individual research projects. Sure, I approve their topics after they submit five-page proposals early in the semester, but they largely have free rein. (Offering regular feedback in small batches and closing loops are key tenets of Analytics: The Agile Way—the course’s textbook.)

I encourage my students to select topics of great personal and/or professional interest.1 For instance, if they want to analyze healthcare data, I tell them to have at it. If they want to try to unlock the secret of sports gambling or fantasy football, they’re free to do it.

I advise my students that this project represents a unique opportunity: Students who complete substantive projects in a specific field can distinguish themselves from their peers when they search for jobs in that field.2 (For this reason, I accentuate the importance of clear, effective writing. Ditto for data visualizations.)

Analytics major Geno Malaty was torn between two very different projects:

Craft beer: a true hobby

The energy industry: a professional endeavor

He visited my office hours last spring and asked for my advice on which road to pursue. I told him that he could choose either. If, however, he wanted to work for a utility in the near future, then Option B offered the highest professional benefit. He stewed on it and ultimately agreed.

After the semester ended, Geno thanked me for nudging him in that direction. He had just landed a fulfilling job at SRP—one of the largest utilities in the Phoenix area. A few weeks later, we grabbed a pizza and he delved into more detail on how his project helped set him up for his new gig.

To quote Bill Murray from Groundhog Day, “That was a pretty good day.”

Righting the Ship

This semester I taught Introduction to Information Systems – Honors for the first time. The survey class moves quickly. Think breadth, not depth. What’s more, my students were freshmen, brand new to the field of information systems. That is, they were all marketing, finance, supply chain, and economics majors.

My hands were largely tied.

Exposing eighteen-year-olds to so much material so fast can be problematic. CIS236 is an in-person class and I could tell from students’ body language that some of them were struggling with the pace of the course. Making matters more complicated in this case, my department insists upon a heavy degree of standardization with 200-level courses. The rationale here is that students should learn the same material irrespective of the course’s specific instructor. In other words, I couldn’t just do whatever I wanted. My hands were largely tied.

What to do?

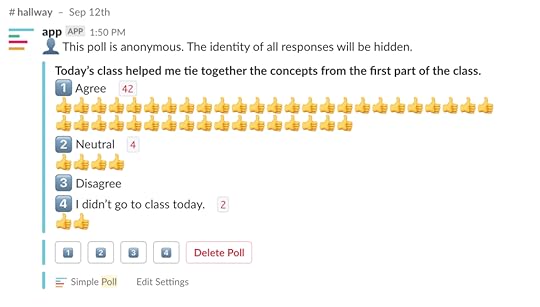

I decided to rework the course coordinator’s prepared materials for the fifth lecture. Rather than hit my students with ever more new concepts and risk alienating them, I tied together most of what we have previously learned in the previous four lectures. I did this by covering the material in the context of several companies with which they were familiar: Amazon and Uber.

Lightbulbs went off. All of a sudden, erstwhile foreign or largely abstract topics such as cloud computing made more sense. How do I know? I asked them via an anonymous Slack poll:

Simon Says

The past year presented the occasional nadir to be sure. Still, moments such as the ones described in this post make those occasional disappointments worth it.

Feedback

What say you?

The post Teaching Highlights from 2018 appeared first on Phil Simon.

December 25, 2018

Thoughts on Reaching 500 Google Scholar Citations

Back when I started writing books in 2008, I largely ignored whether academics cited my work—much less how often. In the whole scheme of things, it just didn’t seem to matter at the time. This feeling continued well into 2014. Although I knew that a decent number of schools used some of my previous texts, I was writing largely for professional audiences, not academic ones.

As I began my career as a college professor, though, my curiosity started to grow. Was my work resonating with researchers? For a slew of reasons, it turns out that academics generally pay a good deal of attention to citations by other academics. Yeah, citation impact is a thing.

It isn’t hard to determine which books or articles resonate with the professoriate using any number of tools—one of which is Google Scholar. Wikipedia describes it as “a freely accessible web search engine that indexes the full text or metadata of scholarly literature across an array of publishing formats and disciplines.” Soon after joining ASU in the Fall of 2016, I claimed my page and signed up for alerts.

At least once every few weeks, Google would send me an e-mail advising me that another scholar cited one of my books or, less frequently, articles on Wired or HBR. I’d click on the link and try to determine the citation’s context. In other words, were researchers praising my work or criticizing it? Fortunately, I can count the number of negative citations on one hand.

Today I’m pleased to report that I’ve hit 500 citations on Google Scholar—something that I’ve seen coming for a few months.

Here’s to the next 500 citations.

I’ll be the first to admit that here’s nothing inherently special about the number 500. No prize awaits me inside or outside of ASU. Also, in terms of context, many long-time academics register numbers far greater than mine. For instance, my friend and muse Terri Griffith of Santa Clara University sports nearly ten times as many citations over her storied career.

Still, 500 isn’t terrible considering the types of books that I write and the fact that I only entered academia in 2016. Also, I have never submitted an article to an academic journal. Finally, the fact that other academics have cited—and continue to cite my work—benefits my employer, the W. P. Carey School of Business, the CIS department, and ultimately me.

Being Right about Big Data

As an aside, it’s interesting to note that more than half of my citations stem from Too Big to Ignore: The Business Case for Big Data (Wiley, 2013). This might be confirmation bias, but I suspected in late 2012 that speed to market with that book was essential. Big Data was starting to blow up at that time; I didn’t want to risk writing another book on a hackneyed subject in 2015. (See social media.) To his credit, my former acquisitions editor at Wiley agreed to fast-track the book. I wouldn’t have signed the contact otherwise.

As an aside, it’s interesting to note that more than half of my citations stem from Too Big to Ignore: The Business Case for Big Data (Wiley, 2013). This might be confirmation bias, but I suspected in late 2012 that speed to market with that book was essential. Big Data was starting to blow up at that time; I didn’t want to risk writing another book on a hackneyed subject in 2015. (See social media.) To his credit, my former acquisitions editor at Wiley agreed to fast-track the book. I wouldn’t have signed the contact otherwise.

It’s rewarding to know that my body of work does not go completely unnoticed among my peers. Here’s to the next 500 citations.

The post Thoughts on Reaching 500 Google Scholar Citations appeared first on Phil Simon.

December 22, 2018

Reflections on Carnegie Mellon 25 Years Later

Around this time a quarter century ago, I graduated from Carnegie Mellon although I walked in May of 1994.

Around this time a quarter century ago, I graduated from Carnegie Mellon although I walked in May of 1994.

Twenty-five years is a long time. On many levels, today I barely recognize the young man who wore that cap and gown.

As I celebrate that anniversary, in this post I’ll reflect on the most important things that I picked up during my time at CMU and how they have helped me throughout my career.

Facility with Technology

As the saying goes, at Carnegie Mellon even the poets know how to code. I would imagine that that remains true today. (In case you’re curious, I didn’t study poetry.)

As the saying goes, at Carnegie Mellon even the poets know how to code. I would imagine that that remains true today. (In case you’re curious, I didn’t study poetry.)

My first semester I had to take Computer Skills Workshop. In hindsight, that course and a few others helped me understand software and devices that would ultimately change the world.

Of course, one can use computers and programs differently. Styles vary. I remember learning early at Carnegie Mellon about the benefits of keyboard shortcuts. Sure, it took time to learn them, but in the long term they save users a great deal of time. I have never forgotten that lesson. To this day, I eschew using my mouse on my computer whenever possible and even record custom shortcuts on my Mac.

What’s more, CMU taught me the importance of learning new tools—something that I’ve carried with me. Exhibit A: Using Slack in the classroom.

Facility with Data

The same comfort holds true with data. I’ve never been afraid to look at data to either diagnose a problem or find a better solution. In fact, I’ve expected it. Looking at data is like breathing to me; I do it and don’t really think about it.

Make no mistake: Plenty of folks reject mind-set. I’ve come across more than my fair share of dataphobes in my career. To the extent that the world is more data-driven than ever, I’m glad that the 18-year-old version of me learned to embrace data. In retrospect, it has helped my career immeasurably.

Learning How to Learn

I would be remiss if I didn’t mention my first proper programming class because it illustrates a larger lesson. If you’re of a certain age, then you’ll probably laugh when you read this: At Carnegie Mellon, I learned how to code in Pascal.1

I’m glad that I learned to embrace data when I was impressionable.

I don’t know of a single university that still teaches that moribund language. Nevertheless, I’m still glad that I took that course nearly 30 years ago. It turns out that, while programming languages change, many concepts remain pretty constant.

For instance, Pascal supported for loops—essentially, a way for software to iterate through a potentially unknown number of steps until it achieves a desired outcome. If you think that concept remains useful today, you’re right. Modern-day, general-use programming languages allow you to do the very same thing. Case in point: When teaching Intro to Information Systems – Honors this semester, I spent nearly two weeks covering the basics of Python. This included—you guessed it—for loops. (I even had some fun creating examples in class.)

I can think of other programming languages that I picked up over the course of my career. SQL and HTML most readily come to mind. The key point is that at Carnegie Mellon, I learned how to learn. I stress the importance of that very thing each semester to my students at ASU. I hope that they are really listening.

Critical Thinking and Problem Solving

Facility with data often goes hand-in-hand with critical thinking—a skill that has only increased in import in the last quarter century.

I remember a project on which I worked in 2008. To make a very long story short, a hospital hired me to solve a particularly thorny data problem that was flummoxing a team of high-priced consultants.2

The project involved corralling, aggregating, and analyzing a boatload of data from disparate sources. To be sure, the sheer complexity of the work hurt my head a few times. Still, I diligently made progress and ultimately solved the problem. In part, I have Carnegie Mellon to thank for imparting the requisite skills to me.

Confidence and Work Ethic

When I attended Carnegie Mellon, student-retention rates weren’t spectacular although they have since improved. The usual suspects back then included its cost, heavy workload, and an, er, challenging social environment.3 Brass tacks: Graduating from Carnegie Mellon wasn’t easy and some of my friends didn’t make it.

Fortunately, I didn’t have to bear the financial burden of my college years. I’ll focus here on CMU’s substantial workload. I can’t recall a single easy class at Carnegie Mellon. Because my parents footed the bill, I felt compelled to go all in. That meant:

attending every class and paying attention

assiduously taking notes

doing the assigned reading ahead of time

turning in all assignments

properly studying for my exams (read: not cramming)

As a result, I received high marks and graduated with university honors.

I like to think that I’m a humble guy. (Playing golf will do that to you.) Still, I’m proud that I was able to succeed at one of the nation’s premier institutions. The lesson for me is that I know that I’m capable of accomplishing my goals if I do the work. If I experience doubts, as I did at one point writing Why New Systems Fail, I remember my time and accomplishments at Carnegie Mellon.

Final Thoughts: Carnegie Mellon never treated me as a customer.

Are college students customers? This question currently provokes passionate viewpoints in academia.

My favorite line in this debate comes from Jeff Gentry. He currently serves as the Dean of the College of Fine Arts at Eastern New Mexico University. In an astute article for The Chronicle, he writes:

My customer is the you 10 years from now, who is going to thank me for upholding college-level standards.

Gentry could not be more right.

In hindsight, my professors and the administration viewed me as a product, not a customer. They never coddled me. I placed my trust in a school, its administration, and my professors, 25 years later, I’m glad that I did. That faith has served me well throughout my career.

Feedback

What lessons have you took with you from college? If you’re currently studying, what do you expect to say about it 25 years from now?

The post Reflections on Carnegie Mellon 25 Years Later appeared first on Phil Simon.

December 10, 2018

Reflections on Supervising More than 100 Capstone Projects

I just wrapped my fifth semester teaching at ASU. On many levels, it was quite the different experience. Most germane to today’s post, for the first time I didn’t teach my normal capstone courses.1 Instead, I taught a survey course: Introduction to Information Systems (Honors).

Professors can manage capstone courses in several ways. I choose the method that requires the most work for me but the greatest benefit for my students. This entails hunting down people and organizations with data and technology needs and meaningful projects. Even though I have developed a few shortcuts after more than one hundred of these things, it’s no small endeavor.

Professors can manage capstone courses in several ways.

Sure, just like in the real world, often projects break bad. When they succeed, though, the results can be spectacular. Today I’ll cover a few of my favorite ones. Note that I’m intentionally omitting company names to provide anonymity.

Scraping the Web

A firm that specializes in executive compensation engaged a group of my CIS students to pull Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) filings. These documents are the very definition of unstructured data. Manually downloading this information and making sense for even a few companies would have taken a great deal of time.

A firm that specializes in executive compensation engaged a group of my CIS students to pull Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) filings. These documents are the very definition of unstructured data. Manually downloading this information and making sense for even a few companies would have taken a great deal of time.

Fortunately, a group of smart cookies used the Python library Beautiful Soup to scrape largely unstructured data from the Web. The entire script took a long time to run but the results blew my mind. Beyond retrieving gigabytes of data, the team threw in an interactive data visualization to boot. The project sponsor was ecstatic.

Alexa: Do Something Cool

A large financial institution wanted to build a mobile app that would help its older customers apply for loans. Sounds pretty standard, right? Consider that the team built did this with Alexa’s voice-recognition technology.

A large financial institution wanted to build a mobile app that would help its older customers apply for loans. Sounds pretty standard, right? Consider that the team built did this with Alexa’s voice-recognition technology.

Watching the six-student team develop the app over the course of the semester served as one of my highlights in my ASU tenure. Beyond building a cutting-edge app, the students had some fun in the class—a key tenet of my teaching philosophy. I grinned from ear to ear after the following exchange:

Student: Alexa, what is Professor Simon’s favorite band?

Alexa: Professor Simon’s favorite band is…Rush.

Building a Model for a Startup

Finally, in my analytics capstone course, a team three students helping a parking startup build a model for its expansion plans. To do this, the students needed to scrape data, deal with the startup’s founders, handle uncertainty, and think critically—just like they will upon graduation.

Because of the students’ character and work ethic, the team accomplished more than some of its peers more than double its size. Sometimes, less is more.

Simon Says: Watching students turn their ideas into reality is very rewarding.

My experience on IT projects is decidedly mixed. Because of this, watching students succeed while learning important real-world lessons just makes me feel good. It’s that very feeling that makes the professor job worth it.

Feedback

What say you?

The post Reflections on Supervising More than 100 Capstone Projects appeared first on Phil Simon.