Michael Hiebert's Blog, page 12

October 23, 2012

Three Act Structure and Scene Layout in Action

Surrey International Writers’ Conference was Linda Gerber’s four act structure talk (which I’ve mentioned in a previous post, and she broke down Juno and, in my humble opinion, she got it wrong. No offense intended to Ms. Gerber, I think she’s a wonderful person and a great speaker and I really enjoyed that session. I just wanted to break Juno down the way I felt it should be broken down, which is substantially different than hers.

Surrey International Writers’ Conference was Linda Gerber’s four act structure talk (which I’ve mentioned in a previous post, and she broke down Juno and, in my humble opinion, she got it wrong. No offense intended to Ms. Gerber, I think she’s a wonderful person and a great speaker and I really enjoyed that session. I just wanted to break Juno down the way I felt it should be broken down, which is substantially different than hers.

Throughout my breakdown, I’ve cherry-picked what I consider are the integral scenes from the story. They are “emotionally charged, turning-point scenes” that the backbone of the story hinges on. Analyzing them is important.

Okay, so without further ado, here we go:

Juno by Diablo Cody

Plot Summary

The movie is best summarized by its tagline: “A comedy about growing up… and the bumps along the way.” In fact, this is an important view of the movie when it comes to deciphering what the actual climax is (as we shall see).

ACT I

Setup

We meet Juno MacGuff, a witty teenager probably too smart for her own good. The story opens with a Juno voice over of the prophetic words: “It started with a chair.” Then we flash back and see what happened in the chair. Juno and her friend Bleeker (who is a friend with benefits) had “benefits” in it. It’s a chair that is now in a front yard with Juno seated upon it drinking Sunny D.

Inciting Event

Juno soon finds out what she expected: that she’s expecting. She’s preggers.

Debate

Being pregnant leaves Juno trying to decide what to do about it. She tells her friend, Leah, who just assumes she’s going to get an abortion. She asks Juno if she wants her to call the clinic for her. Juno says she’ll call herself.

Juno tells Bleeker, the baby’s father, that she’s pregnant. He asks what she’s going to do about it. She eludes, in a very Junoesque way, that she’ll be “taking care of it”–if it’s okay with him, that is.

He says he guesses that it is.

On Juno’s way out the door to the abortion clinic, we meet Juno’s dad and stepmom, Bren, who’s obsessed with dogs.

There’s a single protester at the clinic. Juno knows her. They strike up casual conversation before Juno goes inside. As Juno walks away, the protester (Su-Chin) yells, “Your baby probably has a beating heart, you know. It can feel pain. And it has fingernails.”

Inside the clinic, Juno finds the clinic very “clinicky” (which is a word I just made up). Juno looks at all the other women, sitting, waiting for to go inside. Suddenly, all she can see is their fingernails. Su-Chin has got to her. The next thing we do is cut away to Leah entering her friend Leah’s house, out of breath and sighing.

She couldn’t follow through with it.

ACT I/ACT II Pivot Point

Juno decides to put the baby up for adoption. She’s made a decision that she knows is about to change her immediate and possibly her far ranging future.

ACT II

Unlike a lot of stories, our subplot doesn’t start right away. Instead we have Juno and Leah going through the Penny Saver ads looking for adoptive parents for her baby. They find a couple that sounds promising.

We cut away to Bleeker in his bedroom. His mom calls to him, telling him that Juno phoned for him earlier. We discover that she doesn’t like Juno very much.

Meanwhile, Juno and Leah break the news of Juno’s pregnancy to Juno’s dad and her stepmom. They tell them about Juno wanting to put the baby up for adoption. Surprisingly, her parents take the news quite well. Her dad says he’s coming with her to meet these prospective new parents. Juno agrees that’s a good idea.

We meet the couple, Mark and Vanessa. They are perfect. They have it all: a good relationship; a nice house; they live in a nice neighbourhood; the whole shebang.

There’s a lawyer present for the meeting. Everyone decides on a closed adoption. So far, things seem to be going swimmingly. In fact, the only reason we’re not bored as an audience from lack of conflict is due to the witty writing which is extremely good.

Subplots

The one and only subplot in the movie takes off now. It will become a very important plot line throughout the remainder of the story.

B Plot: Juno finds out she has common interests in music with Mark. The two of them end up in Mark’s bedroom discussing it for a short while with Juno checking out Mark’s music equipment. This Juno/Mark relationship can be considered the B Plot and it starts now. From here on in, I’ll mark the beginning of any sections where we switch from the “A” plot to the “B” plot and vice versa.

Raising the Stakes / Building the Tension

A Plot: At school, word starts to get out that Juno’s pregnant. However, nobody realizes Bleeker is the father of the baby.

ACT II Midpoint

Time moves ahead pretty quickly. We get to Juno’s five month ultrasound. Juno sees her baby for the first time. Bren is with her. We see that their relationship is far from the stereotypical daughter/stepmom relationship when Bren sticks up for Juno after the ultrasound technician says something insulting to her. It’s an emotionally high point in the movie.

Continue Raising the Stakes / Building Tension

Both plot lines continue to rise in tension as they weave back and forth.

B Plot: Juno goes to visit Mark and Vanessa on her own so she can show them the pictures from the ultrasound. Vanessa isn’t home. Juno and Mark wind up watching a horror movie together. They have a lot in common. The audience gets the feeling there might be something happening between them.

Vanessa comes home and finds the two of them together. By her reaction, we get the feeling she thinks there is something between them, too.

Mark and Vanessa walk Juno back to her car and Vanessa mentions she’s worried Juno might back out of the deal once she has the baby. Juno says she won’t.

When she gets home, Bren gives Juno shit for going to Mark and Vanessa’s. She says it was inappropriate.

A Plot: Juno goes to Bleeker’s and finally tells him about the private adoption situation she’s hooked up. She says nobody’s going to tell his folks it’s his baby. Bleeker says he’s relieved by that.

B Plot: We cut to Mark and Vanessa’s house. Vanessa’s painting the baby’s room. Mark tells her she should wait. It turns into a fight.

A Plot: Juno and Leah go to the mall and spot Vanessa there. Juno tells her the baby is kicking and let’s Vanessa feel it. Vanessa says it’s magical.

B Plot: Juno’s on the phone, talking to Mark about a weird CD he made her that she’s been listening to. We’re really getting the feeling that something’s growing between them.

A Plot: Juno finds out Bleeker is going to prom with another girl, Katrina De Voort. This pisses Juno off, even though her and Bleeker are supposed to be just “friends with benefits”. She winds up taking a side of him in the hallway at school.

B Plot: Juno drives in anger to Mark and Vanessa’s house. When Mark answers the door, the first thing she asks is: “Is Vanessa here?” Mark’s answer: “Nope. We’re safe.” Juno: “Cool.” All this dialogue completely points to a covert love affair in the works.

Darkness Closes In

Mark tells Juno he has something for her. He gives her a comic with a pregnant Japanese girl on the front, kicking ass and taking names. The comic is called Most Fruitful Yuki. Mark puts on some music. A slow song comes on he says he danced to at his prom. Juno says she can just picture him slow dancing like a dork. She mockingly places her hands on Mark’s waist and begins to move back and forth. Soon they are dancing.

All is Lost

Juno’s belly bumps up against Mark. Mark says, “I feel like there’s something between us,” and they both laugh. Juno puts her head on Mark’s chest and he pulls her close and says, “I’m leaving Vanessa.”

Juno freaks out about this. We find out, as Juno is yelling and Mark is defending, that Mark did indeed have feelings for Juno, but those feelings were not reciprocal. Mark suddenly realizes Juno is just a teenage girl and calls himself an idiot. Juno begs him not to get a divorce. She wants him and Vanessa to adopt her baby.

On her way out the door, Juno passes Vanessa who asks her what’s wrong. Then Vanessa asks Mark why Juno’s crying. Then, right in front of Juno, Mark proceeds to tell Vanessa that he doesn’t think he’s ready to be a father. Juno runs to her vehicle and drives off.

Dark Night Before Dawn

Juno pulls over to the side of the rode and buckles over the steering wheel, crying–unwinding for the first time since she became pregnant.

Everything has changed now. All hope she had about having a normal life again after all this is now lost.

ACT II/ACT III Pivot Point

Once again, Juno’s life has been turned upside down. She had spent Act II becoming used to the idea of being pregnant and that she would be giving up the baby at the end of her pregnancy. Now she’s forced to re-evaluate everything she’s gone through up until this point. She’s re-evaluating her relationship with Mark and Vanessa (especially Mark). And she’s re-evaluating her decision about not having an abortion in the first place.

Act III

The scene cuts to Bleeker in his room with his guitar and then back to Juno. When we’re back to Juno, she’s laying on the hood of her car, contemplating her future. The camera pushes in as she gets an idea.

Subplots Intertwine

Hopping off the hood, she rummages through her vehicle and finds a crumpled up Jiffy Lube receipt. She unfolds it and pulls out a pen, ready to write something . . . At this point we’re basically back to a single plotline.

The Climax

We go back to Mark and Vanessa’s and see their relationship wrapping up. They’re being coldly civil to each other.

There’s a loud knock on the front door.

Mark opens the door and sees Juno pulling away in her van. There’s a folded piece of paper on the doormat. He unfolds it and holds it up the wrong way. “It looks like a bill from Jiffy Lube,” he says.

Vanessa takes the note, turns it over, and reads it. “It’s for me,” she says.

That’s the climax. It’s a pretty passive climax and actually ends without resolution until later in the denouement, but we know something wonderful was written on that piece of paper. It’s enough of a climax for a small movie like this. In fact, it’s perfect.

Now, let me pause here and say that some of you might be tempted to say that the climax of the movie is when Juno has the baby. After all, that’s a pretty intense part, right? Sure, but it’s not the climax of the story. The story is about Juno growing up. The story’s been all about her getting pregnant and figuring out what to do with the baby, not having the baby. It’s for that reason, I think the actual birth belongs in the denouement and not here.

The Denouement

Juno meets with Bleeker and divulges that she is actually in love with him. He tells her he feels the same.

We move ahead to Juno lying in her room, staring at the celing. Suddenly, she sits up, thoroughly freaked out. She finds her father and tells him her water just broke.

Juno has a baby boy. Vanessa is at the hospital. She gets to see her son. Juno and Bleeker decide they don’t want to see him. He never felt like theirs.

Juno shares a special moment with her dad.

The scene cuts to the nursery in Vanessa’s house, focusing on an antique rocker. There’s a Juno voice over, matching the one that opened the film: “It ended with a chair.”

The camera pans past a framed note on the wall (it’s the handwritten note Juno left on the doorstep on the back of the Jiffy Lube receipt). It says: Vanessa–If you’re still in, I’m still in. Juno.

The final image of the film is Juno and Bleeker sitting on the street curb with Bleeker playing guitar and the two of them singing.

And that’s that.

Notice that Juno doesn’t follow the three act structure rules I laid out earlier to a T. Diablo Cody begins ramping up the suspense and tension even before we transition into Act II with the trip to the abortion clinic. She also puts off the launching of the subplots in Act II until after Juno and her friend have a chance to find a couple suitable to be the adoptive parents of Juno’s baby.

This is an important point that cannot be emphasized enough: the structure is flexible. You can play with it. It’s there to be molded any way you want. Form follows function, always remember that. Do not force your story over some skeleton it simply doesn’t want to go over.

One last item of note: if Linda Gerber happens to see this post, I would love to hear some feedback as to what she thinks of my breakdown compared to hers, as, like I said, they are substantially different.

Until next time,

Michael out.

October 22, 2012

Cry and the Blessed Shall Sing – Sample Chapter

This is chapter one of my new book Cry and the Blessed Shall Sing, which is the sequel to Dream with Little Angels. This chapter takes place seventeen years after a short prologue where a preacher walks into a farmhouse and accidentally kills a young boy while threatening the boy’s father over a land dispute. I really like the juxtaposition in tone between the prologue (which is very dark and powerful) to this, which is very light and funny with characters that anyone who has read the first book will be familiar with.

Cry and the Blessed Shall Sing

Chapter 1

Seventeen Years Later

”Dewey,” I said, “If I say it was blue, it was blue. Why the heck would I say it was blue if it was some other color? It’s not like the important part of the story has anything to do with it bein’ blue.”

”I just ain’t never seen one that’s blue,” Dewey said. “That’s all, Abe.”

”You ever seen one any other color?” I asked.

”What do you mean?”

”I mean, have you ever even seen one at all? Blue or not? This one was the first one I’d ever seen. I mean other than in movies and on TV and all that. It’s not like you see ‘em every day.”

This question seemed to stump Dewey for a bit as he thought it over. Least, I think he was thinking about it. He may have been pondering the aluminum foil he was unrolling onto my mother’s living room floor. “Not sure,” he said. “Not that I can remember.”

”I think that’s enough aluminum foil, don’t you?” I asked. “How much is in a roll?”

He read the side of the box. “Fifty feet.”

”And you had four boxes? That’s two hundred feet, Dewey.”

”I know, but when I paced off your livin’ room, it was ten by twelve. Right there we have a hundred and twenty feet. And it ain’t like the foil’s goin’ to be laid down flat. And I reckon for this to work, Abe, we’re gonna need to go into your dinin’ room too.”

”Well there ain’t no more foil,” I said. “My mom’s already gonna be mad we used up two brand new rolls.”

”I took two from my house, too,” he said. “At least we’re sharin’ responsibility.”

”But the difference is that you reckon this is gonna work. I don’t.”

”It’ll work.”

I sighed.

”We need two more rolls,” he said.

”We ain’t got two more rolls, Dewey. I reckon if two hundred feet don’t do it, two thousand feet ain’t gonna make no difference.”

He thought this over. “You might have a point. At the very least we should see some indication of it workin’. Then we can show your mom and she’ll gladly buy us two more rolls.”

”My mom ain’t gonna want aluminum foil runnin’ around the inside of her house, Dewey.”

”She is when she sees what it does for her television reception,” he said. “Think of how much money we’re savin’ her.”

”How do you figure?” I asked.

”On a satellite dish.”

”She ain’t buyin’ no satellite dish.”

”Exactly.”

”Why aren’t we doing this at your place?” I asked him.

”Abe, my mom’s home. It’s hard enough to do anythin’ at my place when my mom’s not home,” he said. “You’re lucky that your mom works all day shootin’ people.”

”She don’t shoot people all day,” I said. “I don’t reckon she’s ever actually shot anyone.” My mother was the only detective the Alvin Police Department had and if she had shot anyone, she certainly hadn’t told me about it, and it seemed like the sort of thing that she’d probably mention.

”I reckon she has.”

”She hasn’t,” I assured him.

”I bet she thinks about it, though,” Dewey said. “A lot.”

”Can we just get this finished so I can have it cleaned up before she gets home?” I asked him.

Dewey was taking the aluminum foil and rolling it into a sort of shiny rope. He made sure all the new pieces fit tightly against the old ones, making one solid snake that ran around the inside of my living room, starting and ending at the back of the television set.

”So was they all blue?” Dewey asked. “Or were there other colors too? I mean they can’t all be on the same side. Be awful confusin’ if they was all blue.”

”The other ones were red. I saw one of them later.”

”Which ones were the good guys?” Dewey asked.

”How do you mean?”

”There’s always a good side and a bad side, Abe. Were the blue ones the good ones or the bad ones? These colors make it hard to know. Usually they use somethin’ obvious like black and white. Then you know who you should be rootin’ for.”

”Do you root for the good guys or the bad guys?” I asked.

Dewey stopped laying down his aluminum foil pipeline and considered this. “That depends on when in my life you had asked me. When I was little I always wanted the good guys to win. Then I went through a phase where I secretly hoped for the bad guys.”

”And?” I asked. “What about now?”

”Now I guess I just want to see a fair fight,” he said. “Did the blues and the reds both have swords?”

I started to get excited. The swords had been the best part. “You shoulda seen the swords,” I said. “The red blades actually glowed the same color as the knights, and they were huge. They looked so big I doubt I coulda lifted one off the ground. And each sword had a different gem centered in its hilt. They actually had real swords for sale in Sleeping Beauty’s castle, but Mom refused to buy me one. She told me I’d wind up takin’ somebody’s eye out with it or somethin’”

”Wow,” Dewey said, looking off into the distance and seemingly speaking to himself. “A real sword. That would be somethin’. ” His attention came back to the living room and all the foil. He looked me straight in the eyes. “Especially if we both had one. We could have sword fights.”

”Are you even listenin’ to a word I’m sayin’?” I asked him. “These were real swords, Dewey. We couldn’t have sword fights with ‘em. We’d wind up killin’ each other.”

”Still, it’s fun to think about.”

I hesitated. “You’re right. It is fun to think about.”

I looked around the room. Dewey’s aluminum foil rope completely ran along the walls of the entire living room coming right up to the back of the television. We even pushed the sofa away from the wall so that we could make sure it was as long as possible.

“Okay,” I said, just in case Dewey had other ideas, “I think we’re done as much as we’re doin’. Now what?”

”Now I unhook the cable and attach the foil antenna with these alligator clips,” he said.

”Can I ask where you got this idea?”

He shrugged. “While you was at DisneyWorld I started an inventor’s notebook. Turns out I’m pretty smart. I got lots of great ideas. They’re probably worth a million dollars.”

I glanced around the room. My mother was going to have a conniption when she saw what we’d done to it, and especially that we’d used up two brand new rolls of her aluminum foil. “Probably,” I said. “You give off a glow of genius, that’s for certain.”

The light falling in through the window above the sofa was starting to turn purple and orange, which meant it was getting late. This further meant my mother would probably be home soon–unless she wound up working late like she sometimes did. I took another look at Dewey’s tinfoil snake and hoped this was going to be a late night for her.

Dewey hooked up the alligator clips to the screws attached to the electronic box where the cable vision wire normally attached to the television. “That should do it,” he said.

”So now what?” I asked.

”Now we turn on the TV and enjoy havin’ all the stations folks get with satellite dishes without payin’ a cent. All it cost us was the price of four rolls of aluminum foil.”

”It didn’t cost us nothin’,” I reminded him. “We stole the foil from our moms, remember?”

”Even better,” he said, rubbing his hands together. He pulled the button on the television that turned the set on. For a minute the screen stayed dark, then it slowly grew into a picture of white static.

”Works well,” I said, sarcastically. I snuck another glance out the window. The sky had cleared up considerably from this morning. It had been four days since we’d gotten back from DisneyWorld, and every day since we’d returned had been full of pouring rain, including the beginning of this one. This afternoon, though, the sun finally broke through the clouds and cleaned up the sky.

Dewey changed the channel to more static. “Somethin’s wrong. We didn’t hook somethin’ up properly.”

”You know what’s wrong?” I asked. “You’re tryin’ to get satellite TV with aluminum foil.”

”Wait, this has to work. I had it all figured out.” He started rapidly switching channels. Then he came to a channel that was clear as a bell. “Look!” he said, nearly screaming it. “It works! Look how clear it is!”

I had to admit it was clear.

”Told you it would work!” He went around the dial the entire way and found three more channels we could get. All tremendously clear. This seemed to satisfy him immensely.

”So you’re happy with your invention?” I asked.

”I’ll say,” he said.

I looked at him and blinked. “I’m a little confused.”

”About what?”

”Who you will be marketin’ this to.”

”What do you mean?”

”I mean, is this for folk who can’t afford cablevision but happen to have a surplus of aluminum foil and one or two favorite channels they simply cannot live without?” I once again looked at the foil running along the edge of the floor everywhere. “Or will you try and make it some sort of home décor product? Not to mention the fact that you can’t really charge more than the price of four rolls of aluminum foil for it or people will just go out and buy their own and just set everythin’ up for themselves.”

Dewey frowned, perplexed by my complex questions. “It’s a start, okay? I have many inventions. I’ve already filled half a notebook,” he said. “You may have been wasting time in DisneyWorld with blue and red knights, but at least I was doing somethin’ productive.”

Nodding, I said, “Okay. Now, do you mind if we try to get all this put away and see if we can make the television work properly again before my mom gets home from work?”

Dewey glared at me. “You just don’t know genius when you see it.”

”You’re probably right. I don’t. I’ve never really been much of a noticer of brilliance.”

He unhooked the alligator clips. I began to roll up the two hundred feet of aluminum foil.

Just then my sister Carry came into the living room. She’d been out with some friends all day and I hadn’t even heard her come home. “Abe?” I looked up into her blue eyes. Her blonde curls swayed on either side of her face. “What the hell are you two doin’?” she asked.

”Preparin’ ourselves for the future,” I said. “It’s comin’. And it’s full of aluminum foil.”

”And other inventions!” Dewey said. “Wanna see my notebook?”

”Mom’s gonna kill you,” Carry said.

”I know,” I said.

October 21, 2012

SIWC, Over for 2012

Well, I just got back from my final sessions at the 2012 Surrey International Writers’ Conference. I must say, it’s a great conference. This was my fourth or fifth time attending, but it had been at least five years since the last time I went, and I had forgotten what the experience was like.

Since that time, I have attended a lot of cons. Mainly science fiction/fantasy cons like OreCon, RadCon, World Fantasy–things like that. The SIWC is a completely different animal. For those of you who have never gone, I recommend you checking it out. It’s a much more professional atmosphere than the other cons I mentioned (well, except for maybe World Fantasy, which is a con full of stuffed shirts, if you ask me); there’s nobody dressed up as Klingons or pirates walking around. Just a lot of writers (around eight hundred, I think?) and a whack of editors and agents all trying to hook up together. There’s no Tor parties with unlimited free alcohol, thank God. That way only leads to badness.

I did attend an Romance Writers’ of America party last night. It wasn’t bad. I was an RWA member maybe a half dozen years ago, although I never really managed to finish a romance novel. I have an almost-done romantic comedy kicking around somewhere, but it has that weird Michael Hiebert twist running through it that makes it mostly unmarketable.

Anyway, back to SIWC.

And there’s lectures. Even these tend to be on a different level than the SciFi Cons. Not that there’s anything wrong with the sessions at all those other cons, it’s just that at Surrey, you feel much more like you’re in school. I think you learn a lot more. I’m not sure why. Maybe it’s the caliber of presenters? Maybe it’s just because of the air of professionalism that they come better prepared or, perhaps I should say, more prepared to deliver a well-crafted teaching.

Here’s a brief overview of the sessions I attended and what I got out of them (he says, getting out his notepad):

The Deadly Dozen was all about the twelve biggest sins writers make while writing mysteries. Since I write mysteries, I thought this was a pretty good bet to start off the conference on. It wasn’t a bad session, although most of the advice was common sense. Sometimes, though, being reminded of common sense stuff is good. The problems we were told to avoid ranged from things like “Making the killer the least likely suspect” to “Having the cops do the stupidest things possible”. Of course, there were the tried and true ones in there too, like having the female protagonist chase the villain into the abandoned warehouse alone, unarmed, without backup. Stuff like that.

The next session was all about using backstory. I attended this one mainly because it was put on by Diana Gabaldon, whom I’ve had a major crush on since the first time I ever attended the SIWC. Diana is a great public speaker, but she talks really fast. All of the sessions were supposed to run an hour and a half. She went for a half hour and stopped and said, “Well, that’s about all I can tell you about backstory. Any questions?”

Her advice was practical. If you need backstory to write your book, come up with it, but throw it out before writing (or at least 90%) of it. The other 10% can come out naturally through dialogue (providing it is done naturally and not in an, “Well, as you know, Bob . . . ” kind of way) or in flashbacks or weaved throughout the narrative. Something else she does in her historical romances is what she calls shadow narration. Have the author insert a bit of backstory right after a character says something, so it’s almost like author intrusion. Just do it in a way that isn’t so obvious.

The key, she said, is to pull on backstory only when you need it and then to only give out as much as you need to make the reader understand the story. Keep the rest secret. That’s what the backstory is: a secret story you know and the readers only glimpse through the characters’ actions.

She than filled some of the remaining time reading bits from her new book that use backstory in different ways as examples. She’s a great reader. Hearing her read was worth the price of admission.

My final session on day one was Linda Gerber’s Plotting with Four Act Structure. I went to this because I was interested to see what the heck four act structure is, being quite familiar with three act structure myself. turns out her “four” act structure is exactly like my three act structure with a division made at the Act II Midpoint that she then uses to divide Act II into two acts (Act II and Act III), making my Act III her Act IV. Otherwise, it’s pretty much identical.

So I didn’t get too much out of that one. I did actually get to disagree with her on three different points throughout the class, though and that was fun. Sometimes I enjoy being a shit disturber. Luckily, Ms. Gerber is a very nice lady with little to no ego who takes critique very graciously.

That was it for day one. Day two started with a session on researching called Beyond Wikipedia. There was some good stuff here. It was mainly a group session with everyone throwing out questions and answers and the instructor sort of moderating the whole thing. Some great ideas about where to go to find out things for your novel came to the surface, such as: university libraries, old catalogs and newspapers, google scholar (which I’d never heard of), jstor (again, never heard of it), questia (ditto on this one, too), and so on.

I found out there’s a book the size of a doorstop called Cassell’s Slang Dictionary which tells you the first time and place a slang word was ever used. I can see this book being a tremendous addition to my collection, especially for anything I write set in the past. I’m going to try and find a copy online.

I also found out that if you’re writing fantasy, you’re spells should not be cast in Latin the way everyone is doing it (ala Harry Potter), but Hebrew. That’s the way spells were cast back then. Hebrew is considered the first language. Adam and Eve spoke Hebrew.

Next session up was one of the most interesting of the entire conference for me: Taking Control–Advanced Social Media by Sean Cranbury. This one was all about making sure you maximize your web presence and how to get your sales and marketing numbers up using the Internet.

A lot of fantastic ideas came out of this lecture. Mr. Cranbury has a friend who publishes eBooks with sales up in the 120,000 unit range at $ 3.99 a pop, and he shared with us the secret to how to attain those numbers. I am anxious to try some of these marketing methods, especially once Dolls is fully released.

I ended up going to two lectures next, because my first choice sort of sucked after fifteen minutes into it. Well, I shouldn’t say that. To be fair, it was probably a decent lecture, just not for me. It was on outlining and, once inside, I realized, since I sell on proposal, my outlining skills are already as good as what was being described by the instructor, so I wasn’t going to get anything out of it. So I quietly left and found myself another class.

Which found me in another of Linda Gerber’s lectures. She’s the one I argued with about four act structure the day before. This time she was talking about writing mysteries for teens and tweens and I must say, it was a great session. I found out later, she’s got a lot of books published. She knows her stuff.

There was a bit of spill over between this session and the one I’d taken the morning before on the twelve deadly sins of mystery writing, but all in all I still got a lot out of it. I especially enjoyed her lists of common stereotypes in young adult fiction to avoid. Things like best friends always being red heads, token black friend who is usually a girl, nasty girl whose on the cheerleader squad, quiet and artsy girl who hangs out by herself. The list went on and on.

Again, there were a lot of common sense things mentioned as far as mystery goes, but it’s good to be reminded of these things because we do forget. That’s why we continue to see them showing up in books, movies and television shows. Especially television shows:

Avoid “the clue that changes everything”

Avoid “Deus Ex Machina”

Don’t use schizophrenia as a plot device.

Don’t solve the story’s main problem with adult intervention.

Avoid cliches.

Remember the rule of Chekhov’s gun: if you show a gun in chapter one, that gun had better be shot before the end of Act III.

That ended day two, which led to today. Today was a short day with only two lectures. The first one I had been dreading all weekend because, as some of you know, I have gut-wrenching, terrifying stage fright. So what do I decide to participate in? The session on Reading Your Work. And we were supposed to bring some of our work with us to read in front of the group.

I was third. My knees knocked. My arms shook. By the middle of my piece, it was terribly obvious. I actually stopped reading and said, “This is crazy.”

The instructor was very nice and said I have a great reading voice and that nobody noticed me shaking at first, but it had gotten worse as I went which she found very peculiar. I said, “No, it’s not peculiar. I’m terrified.”

Anyway, she gave me some helpful suggestions and was very supportive.

I think she was just being nice.

And that brings me to my final session of the day which I just got home from. It was called Editing Your Own Work and the instructor didn’t seem to know what it was actually on. She sort of asked the class what they wanted to take away from it, and everyone came up with something different.

It was good, though. She gave us an interesting exercise. She handed out a sheet of prose and told us to edit it. I put maybe a dozen marks on it. I was careful to make sure that every mark I made I could back up with why I had done it–for instance, there were places where a semicolon had been used to split two predicates that had a common subject, which, to the best of my knowledge is a no no.

Anyway, the long and the short of it is: the piece was taken directly from a published book by Hemingway.

Go figure.

I still stand by my edits. I guess when you’re Hemingway nobody edits your punctuation on you.

That’s about it. All in all, a good conference. I think I’ll be back next year.

Michael out.

October 19, 2012

Building Scenes

Welcome to my next installment of writing tips for those of you who might be in need of them. I’m posting these in hopes that they might be of some help to people along their way to becoming published authors because a lot of this stuff was stuff I had to learn the hard way; I just kind of stumbled in the dark as I went, trying different things until I found out what worked.

Welcome to my next installment of writing tips for those of you who might be in need of them. I’m posting these in hopes that they might be of some help to people along their way to becoming published authors because a lot of this stuff was stuff I had to learn the hard way; I just kind of stumbled in the dark as I went, trying different things until I found out what worked.

My previous tip post was about three act structure and, like that post, this one isn’t meant to be the last word on writing or the last word on anything, for that matter. Everyone has his or her own process, and if you’ve found something that works for you, then by all means stick with it. These little essays just describe approaches I’ve found that work and I publish them here in case they might be of some value to others. Take whatever you want from them.

Dramatic Format of a Scene

Today, I want to talk about scene building. Scenes really go hand in hand with the three act structure. The structure is basically a sequence of scenes that start at the beginning of Act I and end at the end of your book.

There’s a strong relationship between the concept of “Showing vs. Telling” and scene building. Many writers, especially those just starting out, seem to have a hard time with the showing vs. telling thing. Let me see if I can clear up any confusion.

Consider the following paragraph:

John got a date with Amelia tonight. He drove his car to her place and picked her up. After that, John and Amelia went dancing at that new club, Ringo’s. John drank too much and got into a fight. He wound up in jail. Amelia had to bail him out the next morning. She wasn’t too pleased.

This isn’t a scene, it’s a synopsis. It contains an overview of a number of different scenes. Scenes are dramatic, meaning they contain drama. To write this dramatically requires you to unpack the details. How much of them you unpack is really up to you and, in some degree, defines your style as a writer.

I will write the first line of the above paragraph as a scene to give you an example of what I mean:

#

John came home from work late in a rather unpleasant mood. He’d had a fight with his boss and all he was thinking about was having dinner, putting up his feet, and watching the football game on television. Bedtime wouldn’t come soon enough.

That’s when there was a knock on his door. He could tell just by the sound of the knock that it was Tim Jackson, his landlord. Shit, John thought. He’d forgotten to pay his rent.

Tim knocked again right away. He knew John was home; he could see his car in the driveway. Oh well, there was no point in post-poning the inevitable. John answered the door.

“Hi Tim,” he said, scratching his head.

“I need the rent, John,” Tim said. Tim always reminded John of a reptile. It was something about the way his teeth were set in his mouth.

“Yeah. Okay if I get it for you tomorrow?”

“Why is it always tomorrow with you? Every month it’s tomorrow.” Those teeth looked ready to snap any minute.

“Sorry ’bout that, but I really don’t have it on me. I’ll have it tomorrow for sure.”

Tim searched John’s face as though trying to see whether or not to trust him. John didn’t think Tim ever trusted him. “I’ll be back tomorrow. If you don’t have my money . . . ” He never told John what would happen, just made it seem like it wouldn’t be good.

“I’ll have it. Jesus, Tim.”

“Lots of people would love to live here, price I charge.”

“I know. You’re a saint.”

Tim narrowed his eyes. He was trying to tell if John was being sarcastic. Luckily he wasn’t bright enough to pick up on sarcasm. “Just have my money.”

John closed the door and sighed. He had no idea how he was going to come up with rent money in twenty-four hours. Not unless the rent fairy came and left him a check while he was sleeping. Could today get any worse?

As though reading his thoughts, John’s telephone rang. John didn’t even bother considering whether or not to answer it. At this point, he thought, just let the problems pile themselves up.

“Hello?” he answered.

“Hi, John? It’s Amelia. We met a couple week’s ago at Shelly’s birthday party.”

Amelia. John remembered Amelia. Tall, blonde, curvy. Everyone at that party probably remembered Amelia. “Hi,” John said, putting on an air of suaveness he didn’t know he had.

“I was just wondering what you were doing tonight? My schedule sort of cleared up on me and I was wondering if you might want to go out? Maybe go dancing? I’d like to check out that new place. What’s it called? Ringo’s?”

Jack nearly stumbled over his own tongue. “Yeah, um, sure. Yeah! I’d love to. Want me to pick you up?”

“That sounds great!”

“Okay, hang on, let me get a pen.” He grabbed a pen and the envelope containing his overdue telephone bill. “All right, give me your address.” John copied down her address as she told it to him. “Okay, I’ll see you in, say, an hour?”

“Sounds perfect.”

John hung up the phone and smiled, wondering if maybe the rent fairy had come and just left him a present other than the rent money.

#

There, that’s the first sentence of the paragraph above written out as a short scene. Now it’s dramatic. You might think it sucks, and it probably does. I just wrote it off the top of my head. But it fulfills the job of the first sentence. Where the original sentence “told” us what happened (“John got a date with Amelia tonight”), the scene “shows” us him getting the date. It not only shows him getting the date, it also shows John’s thoughts and feelings about it. There’s also some added back and forth with his landlord that I seem to have arbitrarily added. Why did I do that? Because of our next topic:

Conflict

Every scene has to have conflict. In a lot of ways, your scenes are three act structures squished into smaller time spaces. They should have virtually the same elements: a setup, some sort of rising conflict and tension (and maybe suspense), and everything should eventually crescendo toward a climax and resolution.

Conflict is key. Conflict makes us interested and keeps us there. I added conflict by making John unable to pay his bills (I’m not sure how he’s going to afford to pay for his date tonight, but somehow he gets drunk enough to get into that fight).

Remember, you want to keep the conflict and tension rising throughout your book (especially throughout that great expanse known as Act II), and the only way to do that is by writing highly charged scenes, with each one being a little more ramped up than the last. In reality, of course, you can’t possibly have every single scene more conflicted than the one before it, but you do want to make sure you average a nice rising effect.

Energy

Another aspect to writing scenes is energy. This is something Robert McKee goes on and on about in his great book Story. Energy is either positive or negative. It means your character is either feeling up or he’s feeling down. The energy of a scene has to move. Every scene should show movement of energy one way or another. It should either start off positively charged and end negatively charged, or it should start off negatively charged and end positively charged.

This is yet another reason for me to give John all his problems with the boss and the landlord (and even mention the unpaid phone bill). I wanted to start the scene off negatively charged because I knew it was going to end with him getting the date of his dreams which would leave it ending in the positively charged position.

If you use index cards to map out your scenes (some writers are crazy for index cards and plot out their entire story on them), you can put a +/- or a -/+ in the top right hand corner to designate the energy movement of a particular scene.

Now, there’s one further thing Robert McKee preaches. He says that your scenes should line up so that positive ending scenes butt up against positive starting scenes and negative ending scenes butt up against negative starting scenes, so you end up with scenes looking like this: +/- -/+ +/- -/+.

I think that’s being a little too anal retentive and asking for major headaches later in your writing process if you happen to want to move one scene from somewhere in your novel to someplace else. You’d have to redo every other scene somehow to keep the pattern intact. But who am I to argue with a master like McKee? If it works for him, it might work for you.

Special Scenes

There are a few scenes on the hero’s journey (in other words, throughout the three act structure) that require special attention. You should spend extra time on these to make sure they are highly charged emotionally and that they are well-paced. These are the cornerstone scenes I talked about in my three act structure post: The Inciting Event, The Climax, and the Pivot Points between Act I and Act II, and Act II and Act III.

You will generally find that, as you close in on the end of your novel and ramp up to your climax, your sentences will naturally begin to shorten and, quite possibly, your paragraphs will as well. This is because you automatically feel the subconscious need to increase the tempo as things come to a head. The same might very well be true of your Inciting Event.

The Pivot Points are very emotional places in your story which might benefit from some good internalization. Generally, these are times when the characters are going through inner changes which you might want to draw the reader’s attention to. Sometimes this can be tricky, as the characters themselves might not be aware of the changes coming over them.

Scene Composition

You want to come into scenes late and leave early. Not doing this is a very a common problem with a lot of authors, even authors who’ve been writing for some time.

What I mean by coming in late is that you want to start the scene at the latest possible time you can without losing any valuable information. It’s a lot like starting your novel. You don’t want to show your character from birth and you probably don’t want to show him sleeping and getting out of bed. You want to start on action. You want to pick up right where things get interesting. You want to hook the reader.

And you don’t want to overstay your welcome. Again, here scenes are much like your novel as a whole–once you’ve finished showing the reader what is essential to the story, get out. You’re done. If you have characters saying, “Goodbye,” a lot in your scenes, or getting into cars and driving down streets (although, sometimes getting into a car and driving away is a good way to end a scene), you’re probably going on too long. Once again, you want to end on a hook or, in this case, you’d probably call it a cliffhanger.

Cliffhangers don’t all have to be about damsels in distress tied to railroad tracks with trains only yards away from running through them; they can be little things. I’d consider the ending of the short scene I wrote above a mini-cliffhanger. It leaves the reader with at least a little bit of a question. Who is Amelia, anyway? What’s going to happen on this date? Is John in over his head? It seems like nothing else in his life goes right . . . how is he going to botch tonight up?

It’s really more in the phrasing than the content when it comes to ending scenes well. Although, sometimes, especially when writing thrillers or mysteries, you really can end on a good cliffhanger. If you get the opportunity, by all means, pull out all the stops!

That’s about it for building scenes. Just try to keep everything interesting with lots of conflict and tension and make sure you’re showing more than you’re telling. And always remember that the more you write, the better you get.

Michael out.

October 18, 2012

Off to the SIWC Tomorrow!

Heading to the Surrey International Writer’s Conference bright and early tomorrow morning. Pumped!

I didn’t submit anything to the contest this year, but looking forward to the lectures. I’ve already got everything I’m going to attend picked out.

Won’t be online much, as my days between now and Sunday will be pretty full. I’ll try to post an update nightly if anything worth talking about happens, otherwise I’ll put up a recap when I get home on Sunday.

Michael out.

October 16, 2012

Three Act Plot Structure In Detail

A few weeks ago, I posted an entry about my writing style and how I usually approach my work using a three act structure. I mentioned that, until I had at least the four major cornerstones of that structure in place, I couldn’t really start writing. Those cornerstones are: the inciting event, the resolution, and the pivot points between Act I and Act II and Act II and Act III.

Today I’d like to go into a little more detail on my structured approach for anyone who might be interested. There are quite a few books out there that describe different methods of using this as a template, but most of them tend to overcomplicate things. I think I’ve managed to get the process down to as little parts are needed to successfully write a book without getting bogged down in process.

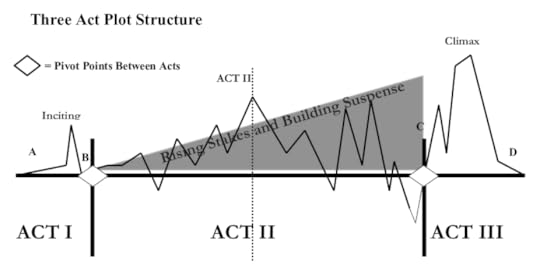

For the sake of those who may have missed it, here’s the graph of the three act plot structure I posted last time:

The first thing I want to do is clarify what I mean by “pivot points”. These are kind of confusing, because on the surface the pivot point between Act I and Act II (the place in your story where your protagonist crosses the threshold into the “new world” where there is no way of ever going back) seems to be the same as the inciting event.

It’s not.

Think of the inciting event as the initial big problem thrown at your story. The first part of your structure is your setup which shows your protagonist in his “normal world”. This is him as he is and has been every day of his life. In showing him here, you want to give a hint that things aren’t as great as they could be. The protagonist might be oblivious to this fact. Indeed, many are. That’s where we get the term “reluctant hero” from. Many protagonists think things are fine and dandy, even after their world starts erupting around them.

Once the normal world has been established (and this should be done as efficiently as possible because all time spent in this portion of your book is before the story starts, read: boring to the reader) you need to throw a wrench into the works. This is the inciting event that will kick off the story. It might be a meteor hurtling toward Earth or an iceberg getting in the way of the protagonist’s ocean liner or some storm troopers killing his uncle and aunt over a couple of droids or your hero’s favorite child getting a Buzz Lightyear for his birthday. Whatever it is, it’s a huge disruption in the hero’s life.

Now the protagonist is left with a choice. This is something important that is easily missed. The choice has to exist in the story. Does the protagonist act on the event, or does he simply ignore it? I call this stage the Debate stage. It can be anywhere from a paragraph to pages in length and it’s important because it’s during this stage that a reader first gets a glimpse of real characterization. We see a bit of what makes your character tick.

Now, we all know eventually the character’s going to act or we don’t have a story. But what’s it going to take? Some heroes are just ready to enter the fray. Some require a little guidance. Maybe a wizard visits his hobbit hole with some dwarfs and convinces him that heading out on a quest is actually a good idea after all.

The wizard in this case is acting as a Mentor which is probably the most common archetype that appears in stories. Knowing about archetypes can be very helpful while you are writing. I will talk about them in a later post. But just know that Mentors have a habit of popping up right near the end of acts, and they’re especially fond of the end of Act I (so is another special and very common archetype called a Threshold Guardian, but I won’t go into details about him here).

Whatever it is, the protagonist’s conscience, the persuasion of a Mentor, the advice of his friend he calls nightly on the Psychic Hotline, something finally ends the Debate phase of the story and the hero decides to take whatever action is needed to get him across the threshold from Act I into Act II. At this point in the story, he knows there is no turning back; he knows his life has now changed forever. It is because of this knowledge and whatever changes he just went through to arrive at the decision to act that we have an Act I/Act II pivot point.

This essentially describes what the pivot point is. It’s an emotional change in the character. It’s growth. Admittedly, it’s not very much growth compared to what we’ll see throughout the rest of the book (especially during the next act which makes up by far the largest portion of the story), but it’s growth just the same. Growth is what writing in the three act structure is all about. You want your protagonist to start one way and finish another. The bigger the difference between A and B, the more emotional potential your book will have. The technical term for this change is character arc. Your protagonist has to arc, and he has to start arcing right away. It’s good if other principal characters arc too, but it’s vital that your protagonist does.

Okay, now we’re past the pivot point and into Act II proper. This is a very common place to launch your subplots.

Before I go any further, I want to point something out. A lot of you might feel I’m trying to make you follow a formula with this “three act structure stuff”; like I’m trying to make all your writing come out one way and one way only. Let me assure you, there is nothing formulaic about it. You don’t have to follow all the rules. When I say things like, “This is a very common place for…” it doesn’t mean that’s the end all be all rule. Not every phase of the structure has to go where I lay it out here. You don’t even need to include every phase. You can juggle them around. You can add your own on top of them.

The way I like to put it is: we’re talking about form, not formula.

Think of the structure more like the structure of a house. Houses don’t follow a formula, but they are definitely built on structures. Yet, every house can be completely different from another. The structure is just there to make sure the house that is built has proper support. With the structure in place, the builder is free to make the more important design decisions that make the house unique without having to worry about the things that carpenters already solved for him hundreds of years ago.

This three act structure, by the way, goes back a little farther than hundreds of years. Aristotle was the first to describe it.

Okay, back to our subplots. Now you may have already started your subplots in Act I. You might not have any subplots. You might have five subplots and two are already going strong and one is going to start now and the other two won’t start until halfway through Act II. That’s all fine and dandy. I’m just saying it isn’t unusual for at least the major if not all the subplots to launch upon entering Act II.

And the major subplot, classically, involves a love interest.

Anyway, welcome to Act II. It’s daunting.

You’re sitting at your computer, looking down the barrel of a very long gun trying to even make out Act III and it’s nowhere in sight at this point.

Act II makes up a huge percentage of your novel. Probably ten percent of your book is taken up by the first act, maybe twenty or twenty-five by your third act and the rest all falls into that big wasteland known as Act II. Most novels sitting in drawers unfinished died somewhere in Act II.

If you read people like Christopher Vogler or Blake Snyder (especially Vogler) they try to give you little milestones throughout Act II–they have more fence posts lining their three act structures then me, making it look as though it makes the task easier, in the same way breaking up a big to do list into a bunch of little things makes it seem easier.

I don’t find that works for me. My act II is pretty barren as far as milestones go, I’m afraid. I just go with my gut. I will give you some hints, though, and a few places along the way where you have to stop and sight see.

First, always make sure your tension and your stakes are moving upwards. Keep the suspense up. There’s a great rule in writing: tell only what you need to, nothing more. Don’t tell anything until you need to. Hold everything back.

Put your protagonist in tight spots, get him out, and then put him in tighter spots. If you have a romance going on in either the foreground or the background, you already know the drill; we’ve seen it in movies enough that we can just feel how it should go: boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy struggles to get girl back. That’s the hard and fast rule that always works. Just make yours work in new and exciting ways that nobody has ever thought of before.

Keep this up for the next hundred, hundred and fifty pages and you’ll be in full swing. If you start running out of ideas, have the men with the machine guns fall through the ceiling (don’t really do that–it’s been done to death now. Do something different, but just as surprisingly ridiculous. It usually works and takes your story in a direction you never expected it to go). Keep this up and you’ll soon hit the next major point in my structure which is:

The Act II midpoint.

This is the very middle of your novel, or pretty close to the middle anyway. This is an important place for you the writer and for us, the readers. It’s a great place for you because you get to relax a bit and do something different. If you watch a lot of movies or read a lot of books, you’ll start to notice that what every great story has near the middle is a pseudo-climax. You can build it just like you would the final climax to your book, only make sure your final climax is going to outshine the one in the middle.

I’ll give you an example. Think of the pod race in Star Wars Phantom Menace. That was almost too much of a false climax. For me, it overshadowed the actual climax, because I’d seen enough Jedi lightsaber battles to last me, well, a lifetime (or so I thought. Apparently, Mr. Lucas thought otherwise). The pod race happens in almost exactly the middle of the movie, right when Act II needed a severe rocket to the gut to get everyone’s attention perked up. And it worked.

Think this is only limited to action movies? Nope. All stories. How about the movie The Help? At the start, Skeeter’s interviewing Aibileen but is unable to get any of the other maids to talk because they’re too scared. Almost in the exact middle of that film is when Minny comes into Aibileen’s house during her interview and shouts at Skeeter for taking advantage of Aibileen. The tension builds, and you think she’s going to dissuade even Aibileen from talking as Skeeter tries explaining that she’s on their side. She’s hoping her work will bring change. The tension ramps up and Minny leaves in a huff closing the door behind her in a climactic slam until, a moment later, she opens it again and says, “Okay, I’ll do it.”

It’s a perfect midstory climax.

The Act II midpoint climax can resolve one of two ways: either as a peak (like both the examples I gave; Anikan wins the pod race, Skeeter gets to interview Minny), and it seems for the moment that things simply can’t get any better than they are, or as a down, and the world collapses around the hero and things seem like they can’t get any worse. If it’s a peak, it’s a false peak. If it’s a down, it’s a false down.

The conditions are false because we’ll learn that things can get more extreme than they are, and they soon do as we progress through the rest of Act II, continuing to maintain growing tension and raising stakes and trying to keep up any suspense we can.

Near the end of Act II we hit three major milestones. My terms for these may have been culled from other people, I’m not sure.

The first one I like to call Darkness Closes In. This happens just as things seem to be going all right. If Act II had been a little shaky, things finally seemed to be getting back on track and going okay for our protagonist. He and the reader can probably see progress being made toward whatever goal he has set out to attain. It’s at this point you want to toss a monkey wrench into his life. The bad guys regroup; the dark forces of evil swell; the girl he met at the swarma bar and fell in love with decides he smells to much like a garlic farmer and leaves him for his best friend Gordon who has two different colored eyes.

This naturally leads to the next phase, one that I definitely did lift. I stole it from Blake Snyder (writer of the excellent book “Save the Cat”). It’s called All is Lost.

This is where the hero suffers a false defeat. The hero thinks he’s come so far only to find he can’t possibly go any farther. It’s the end. You’ve seen this play out in countless movies and novels. It’s where Luke knows he can’t defeat Darth because he’s exhausted. Where the Joker in Dark Knight has the bombs on the boat and Batman can’t possibly save everyone with the way he’s devised his plan.

The hero suffers a breakdown. All hope is lost.

At this point, Joseph Campbell says the character must experience death. It doesn’t have to be a “real” death, although that works, too (In Star Wars, Obi-Wan gives up his life so that Luke and his buddies can make to the Falcon and get out before being shot). It can also be a metaphorical death. Either way, something inside the hero must die.

To quote Blake Snyder, he calls this the “whiff of death scene”.

The reason we need this is because the All is Lost point is our Christ on the Cross moment. It’s where the old world dies for good for our hero. His old way of thinking goes along with it, and everything he used to be is destroyed. This death clears the way for what he can now become.

My final phase of Act II is something I call The Dark Night Before Dawn. This may be only a few seconds for your hero or it may last five minutes. It’s the point right before he musters every last ounce of energy he has left and reaches deep down inside and pulls out that last, best idea that will save the day, which will happen in Act III. Right now, that moment is nowhere in sight. He’s out of ideas and out of strength.

This is a primordial story point. We’ve all been there: hopeless, clueless, drunk, stupid, sitting on the side of the road with a flat tire and no car jack (hopefully not all at once). Then, and only then, are we able to admit our humility and our humanity and give up our control and let fate hand the rest.

This plot point is all about humility. You want to show your hero has been beaten and knows it; show us that he’ll learn from this lesson.

You also want him to exhibit humility in a way that doesn’t knock your readers over the head with it. In other words, do it subtly.

We now hit our Act II/ActIII Pivot Point. By now, I don’t think I need to do much explaining on this one. You can see the emotional state represented by this stage of the structure. This is why it’s one of the four key states I need to have in my head before I start writing. The emotional state of my protagonist at this point in the book–right before I head into my climax–is a very important one, indeed.

Entering Act III is traditionally where all your subplots intertwine and tie up. Classically, it’s in the tying up of the romantic subplot that the idea for solving the ultimate problem of the protagonist comes from, but like everything about this structure, feel free to vary your mileage. Generally the hero gets the girl and the solution at the same time. However you do it, somehow the hero gets a potential solution to his predicament. Hopefully, it’s smart and fresh and something we didn’t see coming from a light year away.

Note that if you don’t tie up all your loose ends here, the best place to probably do it at this point is to wait until the denouement because you don’t really want anything to get between you and the resolution of your book now.

Next step is the climax. Things start wrapping up quickly now. Solutions are applied. If you’re writing a comedy, the main plot and subplots end in triumph for our hero. If you’re writing a tragedy, they end in death. If you’re being ironic, the hero doesn’t get what he wanted but discovers afterward his life is better for being unsuccessful.

The climax usually entails disposing of bad guys in ascending order. Henchman go first, then the boss. The main cause of the problem, whatever it is (a person or a thing) must be completely taken out. Movies supply endless examples. Look at Kill Bill, Lord of the Rings, The Avengers, etc.

But it’s not enough for a hero to just be triumphant. As I already said, the most important thing is character arc. Your protagonist has to change. He should have been gradually changing all through the tests and trials of Act II, but it’s not until the end of The Climax that the change has become final and complete.

And it must become final and complete in an emotionally charged and satisfying way. The hero must experience a resurrection of sorts, corresponding to the metaphorical death he went through at the All is Lost stage. Everything that has happened up to this point should have purposely led to this moment.

To quote Robert McKee, author of “Story”: “The story must build to a final action beyond which the audience cannot imagine another.”

That’s quite a task to undertake, don’t you think? Nobody said writing would be easy

After the climax, you’re pretty much done. In fact, you want to finish as soon as you can. The story’s done, so get out at your first chance. Everything written after The Climax is called The Denouement.

The Denouement is basically the bookend to The Setup at the beginning of the story. It’s a chance for readers to catch their breath after The Climax. It primarily exists for two reasons: first, it gives you a chance to wrap up any loose ends, and second (and more importantly) it gives your readers a chance to see the hero back in the real world having gone through his ordeal.

The world should not be the same as it was in The Setup. The protagonist has changed and with that change, his world has changed. The world is a better place for him having gone through all he did. This is a very important scene and without it your story would lose much power and meaning.

Well, that about wraps up this post. Sorry, I sort of went on a little longer than usual. Hopefully someone actually was interested in what I had to say.

Next time I’m going to talk about scene writing. And I plan to do another post on archetypes. Neither of those will be as long as this, I hope

Until then, Michael out.

October 15, 2012

Cry and the Blessed Shall Sing Proposal: Take 2

So now I’m back to working on my proposal for the sequel to Dream With Little Angels, a book called Cry and the Blessed Shall Sing which I think is stronger than the first.

At one time, I had the proposal completely finished and sent it off to my agent for review before sending it off to Kensington for their approval. However, it would seem my tactic of taking sections of the text that I didn’t feel like figuring out in advance and simply blocking them out in the synopsis with phrases like “The mystery grows here with suspense and intrigue,” didn’t slip past her eagle eye vision.

At one time, I had the proposal completely finished and sent it off to my agent for review before sending it off to Kensington for their approval. However, it would seem my tactic of taking sections of the text that I didn’t feel like figuring out in advance and simply blocking them out in the synopsis with phrases like “The mystery grows here with suspense and intrigue,” didn’t slip past her eagle eye vision.

So she made me go back and actually flesh out the whole story, even though I complained that I think leaving some aspects of the story to work themselves out organically during the writing process makes for a much fresher finished project. I still believe that’s true, although I must admit my intentions may have been driven more by laziness and less by some sort of altruistic belief system. Besides, when I told her this, she had a valid point: I’m not really tied down to what I put in the proposal. Just make it work and if something better comes along while I’m crafting the story, go with it.

Actually, once I sat down and started carving out the missing parts I found some pretty golden stuff. I don’t think anything better is going to come along. It might polish up, but I think I managed to hit a pretty nice treasure trove already. This book’s going to be very rich with story and characters and have a lot more backstory I can draw on if I need to, but the nice thing is I don’t HAVE to.

So now I have to go back through my proposal and insert all the new stuff I came up with; the backstory and the scenes and make sure it all flows together nicely and sells itself the way it should. Hopefully that won’t take too long. This is one of two proposals I’m shopping right now. I’m still waiting to hear back from my agent on the other proposal. I think it’s pretty solid. I’m just as excited about that book as I am about Cry.

Well, maybe that’s not true. Maybe Cry and the Blessed Shall Sing is a little closer to my heart only because it’s in the same world as Dream With Little Angels;

Once again, it takes place in the south. Same mythical Alabama town. Alvin, population: almost none. Same main characters. Most of the story is told from the point of view of the now-twelve-year-old son of the town’s only detective (he was eleven in the first book). I say most of the book. In Dream I had every scene from his point of view and, looking back, it was just too constrictive. From here on in, I’m going to tell as much as I can from first person, but cut away when I have to and go into third person. It just gives me a lot more flexibility and cracks my ability to work new things into the story wide open.

All of this adds up to me being very excited about the prospect of this new book. I love writing these characters. Especially twelve-year-old Abe and his friend Dewey. I can write them for hours and never get bored. I honestly don’t know where they’re going to take me until I sit down and just let them start talking with their southern accents and Dewey’s absolutely drop-dead stupid ideas.

I hope y’all will pick up a copy of Dream With Little Angels when it comes out in July 2013. It’s a pretty tragic book as far as a mystery goes, but it’s got some fun parts in it as well.

Michael out.

New YA Book Finished

I have finished my next YA title. It’s a rather strange book, called Darkstone: The Perfection of Wisdom. It’s pretty much done, other than a final edit.

I have finished my next YA title. It’s a rather strange book, called Darkstone: The Perfection of Wisdom. It’s pretty much done, other than a final edit.

What makes it strange is that it has a very strong Buddhist aspect to it. The protagonist is a Buddhist monk who is also (brace yourself) a superhero. That’s right. A full-fledged, costume-wearing, crime fighter.

I know. On the surface it sounds ridiculous. When I first started writing it, I was kind of joking as I wrote. I just had nothing else to work on, but after about ten thousand words, it sort of took off and the weird part? It works. At least for me it does. And I’ve let a few other people read it too. I’ve had lots of feedback ranging from extremely positive to slightly critical–slightly critical being only that I spend a little too much time with the Buddhist parts and the reader was worried that young people might find that boring. She thought I would be better off spending less time there and more time tussling with the bad guys.

But that really isn’t the point of the book. The point of the book was to try and bring a big topic like Buddhism to a young generation of readers in a way that they might not only be able to understand it, but also enjoy it–and I think on that level I’ve actually succeeded somewhat. I’ve had it read by a Buddhist instructor to make sure my Buddhism references are all accurate. The real problem I see with this book is going to be trying to market it. It’s tough enough promoting a book that fits into a natural genre slot. This one has no real home anywhere. I’ve been racking my brain and thinking as much outside the box as I can trying to come up with different ideas to get my product into the hands of people who might enjoy it.

I have a tremendous cover artist who has shown me some concept sketches so far that have just blown me away. I will be sharing those once he gets a little farther along with them.

All in all, the book’s a fairly mature read. I think it’s a fourteen-year-old plus title–at least that’s probably the age where a reader will really begin to understand and appreciate what I’ve tried to do with the main character. As you can imagine, being a Buddhist monk and a superhero causes a lot of inner conflict (and outer conflict) so there’s a tremendous amount of complexity to the character. It actually makes for an extremely interesting read, imho. It’s also quite funny in places.

I’m just amazed I was able to finish it at all. Like I said, when I first began it, I thought there’s no way the idea would ever work. It just goes to show that if you stick with something, even the weirdest ideas can come to fruition.

Michael out.

Paper Dolls!

In honor of the imminent (well, not so imminent, but maybe in the next month)  release of the trade paperback version of DOLLS, I’ve added a new section to the website. You can now print out your very own sheet of paper dolls and paper doll accessories! You can even recreate the doll on the cover, although you have to supply your own blood.

release of the trade paperback version of DOLLS, I’ve added a new section to the website. You can now print out your very own sheet of paper dolls and paper doll accessories! You can even recreate the doll on the cover, although you have to supply your own blood.

This is the link to the dolls and accessories on the site. Just click the little printer icon in the top left corner of the screen, and you’ll be off and running!

Michael out.

October 4, 2012

Anatomy of a Town

Lately, I’ve been discussing writing resources and how different writers handle them; whether they use something like Scrivener to switch back and forth quickly between their manuscript and their data, or if they have some other way.

Today I want to discuss building things like, well, buildings and towns. When I wrote Dream With Little Angels I had to do a lot of this, and it soon became somewhat messy. I wound keeping everything in a big notebook.

For simple buildings, like the houses of main characters, I was able to just remember the layouts in my head, but for anything complex, I generally jotted down a sketch or two.

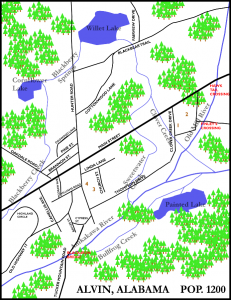

When it came to the town, that was a whole different thing altogether. I started off just throwing out street names when I needed them and sort of guessing their relative position to one another, but that soon became unwieldy. I needed to draw a map. So off I went once again to my notebook and actually drew a completed map of my town, using names for things like creeks, and trails, and roads that I managed to dream up with the help of friends I have who used to live in the south.

Luckily, before that project was finished, I scanned that entire notebook into digital format, because now that I’ve started the sequel to “Dream”, I need the map and all the rest of the data once again and, of course, the notebook is nowhere to be found. But the digital scans are right there on my hard drive with all the rest of the original work for the first book.

This time, though, I went one step farther and actually created a digital version of the map in Photoshop (see image). It’s not pretty, but it works.

I’m just wondering what lengths other authors go to in order to make sure all their information is cohesive throughout their book? I tend to be a little anal retentive when it comes to this sort of stuff, but I think this might be a case where being anal retentive isn’t such a bad thing.

Michael out.

Michael Hiebert's Blog

- Michael Hiebert's profile

- 99 followers