Michael Hiebert's Blog, page 11

December 13, 2012

Sequel to Dream with Little Angels Picked Up by Kensington

I just accepted an offer my publisher Kensington Books made on my proposal for a sequel to my book Dream with Little Angels, a book I’ve been calling Cry and the Blessed Shall Sing.

That title will now become a “working title,” because part of their offer states that they don’t like the title and it must be changed, citing it as “clunky and too long” (which, I guess, it is–too long, at least). I am not so worried about changing the title. This is part of why I keep going on about making sure you don’t have too much of an emotional involvement with your work. I’m not married to my title. I have no problem deep-sixing it and coming up with something else. Besides, I’m usually pretty good at titles.

Usually.

But that’s when I’m writing on my own terms, in my own time frame. This will be the first book I’m actually writing under contract, where I have to produce words at a certain pace because I’ve already been paid in advance to do so. That part? That part scares me a bit. I’m not so sure how I’m going to do under the pressure. I’ll probably do fine. I mean, I don’t see why I won’t, given my track record for prolificness, but there’s still that little voice in the back of my brain saying, “Uh oh, now you’ve done it . . . ” I don’t know if you have that voice, but I’ve learned to loathe mine.

At least I have until September to finish it. It’s never taken me that long to write a book once I get going, and I’ve already got the thing outlined and at least ten percent done. Seriously. What’s there to be worried about?

And I am very excited about getting back into this novel again. The proposal I submitted was five chapters long (about fifty-five pages) and had a forty page outline. I really like the story, and I really enjoy the characters. Having been with them for an entire book and now going into a second makes you really feel like you know them. They’re like real people to me, and I think it comes through in the writing.

In a lot of ways, this sequel has a tighter story than the original and, for those who will read both books in order, goes into more depth about the character’s lives.

I’m just really happy that Kensington has enough faith in my work to move ahead with a sequel even before the first book is released. To me, that shows a lot of support for their writers. I’m also very happy I have the best agent on the face of the planet, so thank you, Ms. Adrienne Rosado.

In the mood I’m in, there’s only one way to end this post, and that’s with the words of Tiny Tim: “Merry Christmas, everybody.”

Michael out.

December 12, 2012

Breaking All the Rules-What Indie Authors Can Do That Traditionally Published Authors Can’t

I have a short story anthology being released next month called Sometimes the Angels Weep. It’s being released under my own imprint, DangerBoy Books, which means, in essence, it’s being self-published.

My adult fiction is usually put out by Kensington Publishing Corp. in New York. They will be releasing Dream with Little Angels next July. Dream with Little Angels is a mystery novel set in a small town in Alabama in the late 1980s. So far, critical reaction to it has been wonderful. We’ve got an incredible blurb from New York Times bestseller Deborah Crombie comparing it to Harper Lee’s Pulitzer Prize winning book To Kill a Mockingbird, believe it or not.

So, why am I self-publishing the short story collection? For a couple of reasons. First, I decided a while ago that I wanted to have the control that Indie Publishing gives me for at least some aspect of my career (I guess I’m a slight control freak). I chose to restrain it to my young adult titles and any short story anthologies I might want to release. Short story anthologies generally aren’t tremendously big sellers, so, if they’re put out by a traditional publisher, they can hit the remainder pile pretty quickly. If I release one, though, I can keep it in publication as long as I want.

The second reason is a little more subtle. Publishers don’t like you to “genre hop.” They feel your books (especially your first books) build up specific fan bases that will want and expect certain things from the author. In my case, there will be the expectation of me being a mystery writer (even though, in reality, most of my writing probably doesn’t fall under the “mystery” category at all, and, in a lot of ways, Dream with Little Angels is more of a coming-of-age title hidden inside a mystery than it is a mystery wrapped around a coming-of-age story. If that makes any sense.

I do tend to write a lot of coming-of-age stories, so it makes perfect sense to me.

My young adult books are like this. They fall completely outside the realm of mysteries, and would feel strange to Kensington if I were to propose they release them along with Dream with Little Angels. So, by publishing them under my own imprint, DangerBoy Books, I can brand myself differently for the young adult aspect of my writing career.

Now, the short story anthology, Sometimes the Angels Weep, is another thing entirely because it breaks all the rules. It changes genres within the book itself. There are mystery stories inside this book. One is probably the most successful story I’ve ever written: My Lame Summer Journal by Brandon Harris Grade 7 won the Surrey International Writers’ Festival Storyteller Award, and was later listed as one of the top fifty most distinguished stories published that year by Joyce Carol Oates in The Best American Mystery Stories.

I chose to open the anthology with that story.

But along with that one, there are also quirky stories written in completely different genres. Some are unclassifiable. They’re like romantic comedies, maybe. There’s a few fantasy stories, including a novella-length piece about learning to find love again in the face of death, and a story poem (in the sort of style that Neil Gaiman sometimes writes in) about the tooth fairy. That one was listed in a volume of The Year’s Best Fantasy & Horror. Also included is an almost-novella-length military science fiction piece I am rather fond of.

The collection bookends with another Surrey International Writers’ Conference Storyteller Award winner, a rather tender and touching story called But Not Forgotten.

In other words, I’ve packed this book full of the best ten short stories that, in my opinion, I’ve ever written (I had about eighty to choose from). I cherry picked without caring about genre. I went only for quality.

In the eyes of publishers, I think this would be definitely frowned upon. In my eyes, I think it was a good decision.

Time will decide if I am right.

If you’re interested, Sometimes the Angels Weep will be available in mid-January from Amazon and will retail for $ 10.95 U.S.

Michael out.

Rewriting & Critiquing

We’ve probably all heard the phrase “Writing is rewriting.” But what, exactly, is rewriting?

Most writers loathe the word. I actually look forward to rewriting. It’s during the rewriting process when things start to come together; it’s where things really begin to shine.

But here’s a secret: rewriting is not going through your current writing and changing bits and pieces of it. At least it shouldn’t be. Not unless you’re doing a very light rewrite for a near-final revision.

Rewrites should be just that, complete rewrites. From the top down. Sure, you can draw from what you wrote in the previous draft, but if you try to use that as a basis for the rewrite, your new draft will sit there, lifeless on the page. Trust me, I’ve tried. I’ve tried many times, because, for some reason, it seems like it should be easier to just apply a bit of touch up to the work I’ve already done than to start over. And the simple fact is that it really isn’t.

What I do now is usually write my redraft overtop of my old drafts. If I’m redrafting a chapter, I start at the top of the chapter and just start writing, pushing the old writing off the bottom of the screen. This way, I can see what I had while I come up with a brand sparkling new work that is going to jump off the page because it’s not relying on the previous draft as a foundation to support it.

This is the professional way to write fiction. It’s the only way to ensure that your work retains that sparkle of life that only comes from original words being put down on paper (or typed onto computer screens).

And don’t think you can get away without rewriting. Don’t disparage when you go into your writing group with what you consider one of the best pieces of writing you’ve ever done and someone points out some obvious problem that you should have seen from a mile away (first, don’t ever kick yourself for missing problems in your own work–this is why we have critique groups. We see issues in other people’s work far more easily than we do in our own. It’s because we’re too close to our own writing and have too much of an emotional investment. With others’ work, we have the joy of apathy. We have no emotional investment. We can easily point out the problems).

The point is: you should expect to have to rewrite. Writing IS rewriting.

And maybe you have problems so insurmountable, you have to completely destroy your current vision and start from scratch. Or maybe it just sounds that way. Don’t be afraid to try. You always have the last draft to fall back on, and who knows? Doing a completely fresh rewrite from a completely new perspective may give you new ideas you just would never have gleaned any other way. In other words, don’t be afraid of work. The work is what it’s all about. You’re a writer. So write.

According to its author, Michael Arndt, the shooting script for Little Miss Sunshine was rewrite number one hundred. One hundred. Think about that next time you’re grumbling about your writing group telling you that your protagonist is coming off as unlikeable in chapter six and you should rewrite things to make her a little more engaging.

Critiquing is an art in itself. There are many different critique styles and methods. Many writing groups use the Clarion method, and it’s one I prefer (actually, the one I am most used to is a modified version of the Clarion method, but that is out of the scope of this article), but whatever the critique method your group uses, remember you should always take notes while being critiqued.

There is also a common problem of weighing comments differently by different people in your group. It’s very easy to write off things said by one person because, you think, Well, he’s not that great of a writer. And, so, you concentrate more on the problems presented by the more experienced members.

This is bad, because it doesn’t take a good writer to point out story problems, it takes a good reader. And sometimes, your best writers aren’t necessarily your best readers. Take all comments equally seriously. Also, even if you disagree with a comment, consider that, for the person giving the comment, it was issue enough to bring it up. It will probably be an issue for other people.

You may also not understand the comment. It may make no sense to you. In cases such as these, sometimes it is valuable to look back a few paragraphs or even a few pages and see if maybe the problem the person is critiquing occurred earlier on than when it is being pointed out. This can happen quite often, especially when being critiqued by inexperienced writers. They feel something is wrong, but they don’t have the experience to describe exactly what it is. But don’t discount their feelings. Their description is just off slightly. Maybe you tripped up two pages earlier making it look as though the problem occurred where they think it does.

Good writers are open-minded and do not get attached to their work. The moment you get emotionally attached to your writing, you’re doomed. Your progress will stymie and you’ll end up going nowhere.

Learn to look forward to critique. And especially learn to look forward to the rewrite process. It will only make your writing better and better!

Michael out.

December 11, 2012

Character Growth

Continuing my ongoing discussion about story structure, i wanted to touch on character change and transformation.

Good stories are all about change. This can’t be stressed enough. When you’re writing, you should make sure that not only your protagonist, but even your subsidiary characters go through a dramatic change. To do this, you have to make certain your characters begin the first act flawed in some way and have specific goals. Then, throughout the struggles of Act II and the ordeal of the Climax, they transform like caterpillars into butterflies, becoming true heroes.

You also have to make sure your story starts with something wrong with the world, too. That something will get fixed once the protagonist goes through his transcendence.

Be careful with transforming your secondary characters. You want to make sure your main protagonist exhibits the most growth, because he’s the one your readers will naturally “feel” is the hero of your story.

Also, even if you have a team working together to solve a major problem and reach an ultimate goal, you can only have ONE hero. Think about The Avengers movie. They all participated in the Climax, but, ultimately, it was Robert Downey Jr. who experienced the “death” and “rebirth” after taking the nuclear missile through the hole in the atmosphere. He was also the character who showed the most change (interestingly, it was the Hulk and Thor who exemplified the All Is Lost moment, after being ejected from the S.H.I.E.L.D. craft).

And remember, your protagonist should be the main factor in defeating your antagonist. In a later post, I’ll talk about breaking down the Climax into components. I know I’ve been a little vague in that area to date.

Another important point is that protagonists change on two levels; there’s a visible change and a hidden change. The visible change is the obvious one: your hero, having conquered the antagonist, no longer lives in fear. He is confident. He is strong.

But the hidden change is a change we, as readers, aren’t so aware of. We feel it more than we see it. It’s an emotional change. A divine change. Having gone through his ordeal, your hero has somehow been touched by God.

Often, the B plot will be a major conduit for the divine change in the

protagonist. It can be a love interest dying or finally falling truly for the hero, or it can be the death of a Mentor.

Whatever causes this second, hidden change has to be in your story because the reality is that THIS CHANGE IS THE TRUE STORY YOU ARE TELLING.

One last point that is slightly unrelated is some advice I once received from Gardner Dozois (one time editor of Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine): Your story should be the single most important event that happened to your main character up to that point in his life. Otherwise, what’s the point in telling it?

Start thinking about all this while you read books or watch movies and you’ll find that (for good ones) these points are always true.

That’s it for now.

If you enjoyed this post, be sure to go through my Writing Tips categories for my posts on story structure. This is part of an ongoing series I’m writing about.

Michael out.

December 7, 2012

Update

I haven’t posted for a while, so I thought I’d post a little update. Not that there’s too much to update.

The Dolls trade paperback is finally available. And even after all the time spent trying to weed out every error and mistake in the text, the first thing I did when I got my copy was open to a random page and find a spelling error. Talk about wanting to strangle yourself. Ug.

The Dolls trade paperback is finally available. And even after all the time spent trying to weed out every error and mistake in the text, the first thing I did when I got my copy was open to a random page and find a spelling error. Talk about wanting to strangle yourself. Ug.

But it’s out and it’s pretty clean. It looks nice. I did some fancy stuff with the chapter numbers for the final release, flanking them with ivy so they sort of go with the theme of the book a bit and I played with some of the spacing making the book look and feel a little nicer. In the end, I wound up making the font 12 point instead of 11, so I grew by twelve pages. It’s a nicer looking book because of it, though.

Here’s something exciting: I just ordered the proofs for my new short story anthology! I sort of jumped the gun on this one. I planned on doing a HUGE anthology of basically every short story I’d written that I didn’t think was complete crap and put it out next fall. It would have been around four hundred pages. But I am starting to do readings, and having only a YA book to read from is a bit of a handicap, so I decided to take the cream of the crop as far as my shorts go and do a book sooner than planned. This one has ten stories in it and they are by far my best ten.

Here’s something exciting: I just ordered the proofs for my new short story anthology! I sort of jumped the gun on this one. I planned on doing a HUGE anthology of basically every short story I’d written that I didn’t think was complete crap and put it out next fall. It would have been around four hundred pages. But I am starting to do readings, and having only a YA book to read from is a bit of a handicap, so I decided to take the cream of the crop as far as my shorts go and do a book sooner than planned. This one has ten stories in it and they are by far my best ten.

It’s going to look nice too. It’s 5 x 8 and 270 pages long which will give it a bit of heft. Each story starts with a little preamble with me talking about how it came to be written or something else clever (or not so clever . . . I can never tell when I’m being clever).

The book doesn’t have a specific genre. The stories range from quiet and tender to military science fiction, but they all work together I think because they all ultimately have my voice behind them. The anthology is called Sometimes the Angels Weep and the cover is shown here. It’s actually a wraparound cover with a really nice sunset on the back that was incredibly hard to get text to look good in front of, but somehow I managed to do it.

People are going to start thinking I have this weird infatuation with angels because all my books are titled with them, but I chose the title because nearly every story in the book has one thing in common: it shows the fallibility of humankind in one way or another along with showing how we can strive to be our best and come closest to God. It’s at these times when we strive for greatness that we miss the mark and fail the worst, sometimes, and that is when I see the angels crying. At least for the characters in the stories being told in this anthology. Please don’t read any religious beliefs into that statement any further that that.

I heard from Kensington today. They sent out the page proofs for Dream With Little Angels. Apparently we’re ahead of schedule, so I have until the middle of January to get them back to them. That’s good because our mail service is so bad it could take that long just to send them. Besides, I’m a slow reader. It’s one of my biggest problems (there’s a list. It’s pretty long).

That’s about it for now. Y’all go now to Amazon.com and purchase a copy of the Dolls trade paperback and wait impatiently for Sometimes the Angels Weep. That’s what I’d do if I was you.

Michael out.

November 23, 2012

Making Characters Sound Human

When we talk about “voice” in writing, generally there are two different things we can be talking about–author voice or character voice. Author voice is the overall tone and style that comes through his or her use of the language to convey whatever story is being told. Generally, author voice is something that doesn’t change. It didn’t matter what sort of story Hemingway wrote, you could tell it was a Hemingway story because it had that “voice,” that openness to it that nobody else could quite manage (although thousands tried).

When you think of all the great authors, they all seem to have that one thing in common; they all have very distinct authorial voices. Whether it be Stephen King, Charles Bukowski, William Shakespeare, or Sylvia Plath. And there’s a list of people I bet you never thought you’d see compiled together under one heading :)

I plan on talking about author voice in another post, because it’s something I know a little about and I think it’s vitally important. I’ve been told I have a very strong authorial voice and it comes through whether you’re reading one of my science fiction stories, or romances, or my novel that takes place in southern Alabama in the late 80s and is written in southern dialect. So even though my characters talk with twang, my voice still comes through loud and clear.

But this post is on character voices, and how to make your characters sound, well, less like characters and more like human beings. In other words, it’s about writing dialogue.

Writing good dialogue is a craft that some people seem to naturally possess and others have to work at. The good news is that, like everything else to do with writing, it can be learned, and once you’ve got it, you’ve got it for good.

Let’s start by taking a look at some bad dialogue.

I’ll set up the scene: Bill and Ted are meeting for lunch to discuss a business proposal that Ted is offering to bring Bill in on for a meager investment of five thousand dollars. Bill doesn’t actually have that kind of money, but doesn’t want to let his friend know he’s broke, so he’s playing along that he’s interested. I’m not going to take this scene very far, just long enough to use it as an example.

#

“Hi Bill,” Ted said. “I want to thank you for meeting with me. I think you will like what I am going to show you.”

“Well I don’t know,” Bill replied, laughing. “I’m pretty cynical when it comes to investing my money. I don’t like to just throw it around.”

Ted pulled out his laptop and a binder full of promotional material. He flashed Bill a smile. “Let me have a chance to show you what we have been up to. I think you might just change your mind.”

“Okay,” Bill said.

Ted ran through a PowerPoint presentation and discussed financial projections while Bill tried to feign interest. “So . . .” Ted asked when he was done, “what do you think, Bill?”

“Um. . . I’m sorry Ted, but I think I have to pass.”

Ted’s face fell. “Can I ask why?”

“I just don’t feel comfortable investing in something with a friend for one thing. Also, like I said before, I’m pretty tight fisted with my money. Maybe you should talk to Dave at the office. This might be right up his alley.”

Ted seemed a bit ticked off. He put his laptop back into his briefcase along with the binder. “Yeah, I will talk to Dave. Thanks for your time, Bill.”

#

Okay, first let me start by saying this isn’t really that bad. I was trying to make it horrible and found it hard to write horrible dialogue. This is part of the good news I told you about earlier. Once you know how to write good dialogue, you naturally will continue to do so. Even when you attempt to go for stilted, you end up with just mediocre.

But let’s see if we can do better. I don’t want to restructure the actual stage direction of the scene too much (although, I will do a bit because what happens around the dialogue is part of the dialogue). Mainly, I want to concentrate on the words coming out of the character’s mouths.

#

“Bill!” Ted said, taking Bill’s hand. Bill had stood as Ted approached the table. Ted had arrived late, wearing a pressed suit and carrying a briefcase. He had his hair slicked back. Dave, on the other hand, was in dungarees and a T-shirt. “How the hell are ya, buddy?”

“I’m good, Ted,” Bill muttered as they sat. “Pretty good.”

“Been here long?”

“Not really.” Bill looked down at his coffee cup, half empty.

“I need one of those,” Ted said, looking for a waitress. He made eye contact with one and motioned for her to bring him a cup.

Ted placed his briefcase flat on the table in front of him and put both his palms on top. He stared right into Bill’s eyes. “So . . . how’s the wife?”

“She’s . . . she’s okay, Ted,” Bill said quietly. “You know. Same old thing.” He looked nervously across the restaurant to a bunch of people being seated.

“Glad to hear it.” Ted smiled. He had impeccably white teeth, reminding Bill of a shark. “Still golfing?”

Bill looked away again. “Not really. Threw out my shoulder . . .”

“Ooh, sorry to hear that.”

“Yeah . . .”

“Anyway–” The waitress arrived with Ted’s coffee, cutting him off. She set it down on the table in front of him, making him have to move his briefcase.

“Well,” Ted said, “What do you say we get right down to business?”

“Sure . . . ” Bill said, tentatively. His hands felt clammy.

Ted popped the latches on his briefcase open. They seemed extra loud in the small restaurant. He pulled out a laptop and a binder stuffed with promotional material. He passed the binder over to Bill. “I think you’re gonna LOVE what I have to show you,” Ted said.

“I don’t know,” Bill said, “Stacey and I are pretty tight when it comes to our money. It’s more her than me.”

Ted smiled. “She’s got ya by the short hairs, hey? Well even SHE’LL be impressed when you tell her about this.”

With a bit of rearranging of coffee cups and chairs, he set his laptop up on the table so they could both see it and began running through a PowerPoint presentation describing his investment deal. Every so often, he’d stop and refer Bill to a page in the binder. The presentation was very professional and slick.

Bill felt very warm. A trickle of sweat ran down the side of his face.

The presentation came to and end. “So,” Ted said, “what do you think? I can get you in for five thousand. That’s a pretty sweet deal just for you. We’ve moved up to ten thousand for everyone else at this point. I’m only doing this because we’re friends.”

“Gee, I really appreciate the opportunity Ted . . .” Bill said, “but I don’t know. I think I’m gonna have to pass.”

“Seriously? Can I ask why?”

Once again, Bill’s gaze wandered across the room. “Like I said, Stacey and I are pretty tight with are finances. She doesn’t like me to throw money around. I know this is a good deal. I can see how good it is.”

“You bet it’s good.”

“I know. I can tell.”

“Then what’s the problem?”

“I just . . . I don’t think she’ll GET it.”

“Why don’t you go home and talk it over with her?” Ted suggested.

“Okay,” Bill said, with a sigh. “I’ll do that.”

“Good man!” Ted said, checking his watch.

He stood from the table. Awkwardly, Bill stood too and they both shook hands.”I’ve gotta take off. I have another appointment downtown in twenty minutes. Don’t forget to talk to Stacey about the thing. I’ll call you in a couple days. All right?”

“All right.”

“And give her my love.”

“I will.”

#

Okay, now you’re probably going to call foul and say I cheated because it’s so much longer, but that is a little bit of the point. Real dialogue isn’t condensed in a few lines, it meanders and goes on tangents. Things happen to interrupt it. That’s also why there is more happening in the second scene; everything in it is around the dialogue and, in a way, dialogue related.

There’s also better characterization–we actually see that Bill is nervous–but that’s part of good dialogue too. And notice the structure of the sentences. They aren’t all the same length like they are in the first scene. They vary. Sometimes speakers go on for three or four sentences, in other cases, they say one word and get cut off or drift off. If you listen to real dialogue in real life, people rarely say a complete sentence and hardly ever say a complete sentence without a contraction. You should pretty much use contractions always in dialogue unless you have a good reason not to. Good reasons might be: the character speaking is Data from Star Trek: The Next Generation, he is a God of some sort, he is some sort of being that speaks very formally. Without contractions, a certain level of stiltedness will automatically occur in your dialogue.

Another thing to watch for when you’re writing dialogue is that you’re not playing ping pong. Dialogue shouldn’t just be back and forth, one speaker says something the other reacts with something the other reacts back, etc. There are always multiple levels of things going on. We are always saying one thing and meaning something else. There is always subtext. Half the time, we are playing catch up, still talking about something referred to three lines of dialogue back while the person we are talking to is onto an entirely new topic.

Want to do a neat exercise? Most smartphones have recording software. Next time you’re at a gathering or a party or whatever you call it, place your smartphone in an inconspicuous spot with the recording feature active and just let it record. Then, later, listen to the conversations. Better yet, transcribe them. I actually wrote a short story this way once and it turned out to sound incredibly similar to something in the style of J.D. Salinger.

One last example. I mentioned that my latest novel, Dream with Little Angels (Kensington, 2013) is written in dialect. A lot of editors warn against writing in dialect, because you have to be dead on for it to work. I had no problem selling my book and I think the dialect helped. Here is a scene from that book to give you an idea of how I handled the dialogue. Note that only the dialogue is in dialect, the actual rest of the prose is not. There are also other interesting differences between the prose parts and the dialogue parts. The book is written in first person from the point of view of the eleven-year-old son of the detective solving a murder. Whenever he refers to his mom in dialogue, he calls her “mom,” whenever he refers to her in the prose, it’s always, “my mother.” I do the same thing with the words “reckon” and “think”. In this way, the prose is elevated to a more literary level, even though the book retains the feeling of being placed firmly in southern Alabama.

In this scene, the protagonist (eleven-year-old Abe Teal) and his best friend Dewey (who is at least one burnt sienna short of a box of Crayolas) think Abe’s neighbour is suspicious, so they follow him into town one Saturday morning on their bicycles.

#

Dewey turned out to already be up. He answered the phone on the first ring, which was good, because I didn’t want to wake up his ma. She would have her own concerns, although through the years I had discovered Dewey’s mother didn’t seem nearly as thorough as my own when it came to worrying about or monitoring her son’s business.

“I’ll meet you outside on my bike in fifteen minutes,” I whispered excitedly into the phone after telling him about what I saw.

“Why was he dressed like a cowboy?” Dewey asked. I heard him yawn right before he said it. It annoyed me that he wasn’t already off the phone and getting his shoes on.

“How the heck should I know? Why is he walking down Cottonwood Lane before seven on a Saturday? And the biggest question is why is he carrying a shotgun with him?” I was getting frustrated, because it was questions like these that were exactly the reason we had to follow him. If we knew all the answers, we could just stay home and Dewey could go back to bed the way it sure seemed like he wanted to right now.

“You said the box just looked like it could carry a shotgun,” Dewey said.

“Yeah, but what else would you put in a box like that? Come on, Dewey. It was a cardboard shotgun box if I ever seen one.”

“Have you ever seen one? I never even heard’ve one.”

I thought that over. “No, I suppose I haven’t. Not until this morning, anyway.”

“I’m not sure I should leave,” Dewey said. “My mom’s still asleep.”

“Leave her a note. Tell her you’ll be back before nine.” I reminded him I now had my very own watch.

“I’m still thinking that maybe we should wait . . .”

“Wait for what? We’ve been watchin’ his house going on . . . I don’t even know how long. Now, out of nowhere, I actually see him leave and we have the opportunity to find out what he’s really up to. And you’re worried about your mom because she’s sleepin’?”

“We know he ain’t taking roadkill,” Dewey said. “It came back, remember?”

“We know he ain’t taking it no MORE,” I corrected him. “We have no idea WHAT he does. This is what we have to find out.” I sighed, trying not to get too angry and raise my voice too loud. I didn’t want to wake anybody.

Finally, I convinced Dewey that going after Mr. Wyatt Edward Farrow was not only the right thing to do, it was, by all intents, the only thing to do.

“All right,” he said. “Give me twenty minutes.”

“Twenty minutes? You already used up ten on the phone. We need to catch up with him. You got ten to get here.”

“All right.”

It took him more like seventeen. In fact, I was on the verge of calling him back when I saw his bike pull up outside my yard through that gap in them drapes. I already had my boots on and quietly headed outside using the backdoor, being careful to shut it slowly so it didn’t slam the way it normally did. I grabbed my bike from beside the garage and pushed it gently down the driveway in the still quiet of the early morning.

“What took you so long?” I asked, still keeping my voice down.

“I was in my pajamas when you called.”

“So was I.”

“I was hungry.”

I rolled my eyes. “Fine time to think about eating. Anyway, let’s go before someone wakes up and finds us.”

“Did you leave YOUR mom a note?” Dewey asked.

I nodded.

“What’d it say?”

“Said I was going biking with you and I’d be home by nine. What did yours say?”

Dewey’s cheeks pinkened under the golden morning light. The sun twinkled off the chrome of his handle bars. A few puffy white clouds were stretched across an otherwise light blue sky the color of a dipped Easter egg. “I said we was going after your neighbor to see what it is he does on Saturday mornings dressed as a cowboy.”

I stared at him for what felt like a full-on minute, wondering if he was pulling my leg. He wasn’t. “Now why would you go say somethin’ dumb like that?” I asked.

“Cuz it’s the truth, ain’t it?”

“So? What if your mom calls my mom?”

“I always tell the truth.”

I bit my tongue and thought before responding. “I do too, but just because I left out part of the why doesn’t mean I wasn’t being truthful. Anyway, it’s too late now to worry ’bout it; we ain’t goin’ back to your house to rewrite your note. Let’s go, before we lose any chance of findin’ him. Christ, Dewey, it’s been nearly half an hour since he left.”

We kicked off in the same direction Mr. Wyatt Edward Farrow had been walking. “I figure he’s likely gone downtown,” I said. “Although I doubt too many shops or anythin’ is open so early on a Saturday morning.” I said this, although I didn’t rightly know whether or not it was true. Maybe all this time I’d been thinking I was one of the only people who woke up bright and early on Saturday mornings when the truth was it actually turned out most folk were just like me, and my mother and Carry were the exceptions. I guess me and Dewey were about to find out.

While we rode, I told Dewey about me and my mother finding Carry and her boyfriend the night before. Most of the story I went over rather quickly, but he made me slow down at several key areas. The first was when I described what Carry was wearing in the back of that car. I knew he’d be interested in hearing that, I just never realized how interested. He must have asked me nearly ten different things about it. Finally, I just got mad.

“She was in her bra. What else do you need to know? Why is this so important?”

Dewey shrugged. He was coasting beside me. “I dunno,” he said.

“Well, let’s get past it, then, all right? I mean heck, you can either imagine what she looked like, or you can’t. I don’t see how I can provide any more details than I already have.”

He stopped me again when I got to the end and told him about how my mother pulled out her gun, pointed it straight at Carry’s boyfriend, and—the most important part, I thought—used the word. Not once, but twice.

“Really?” Dewey asked. This interested him even more than Carry’s undergarments. “Was the gun loaded?”

It was my turn to shrug. “I’m assuming so. My mom said it was.”

“And she used all them words?”

I nodded. We both swerved around a parked Chevy truck. “I couldn’t believe what I heard,” I said. “She even said she was gonna blow his balls off, or something to that effect.”

“Wow.”

When Dewey was finally satisfied that he’d wrung every detail of the story he could from me, we fell into silence for a while. I rode the lead, taking us up to Main Street.

“How do you know this is the way Mr. Farrow went?” Dewey asked.

“I don’t,” I said. “I just figure if you’re gonna go out on a Saturday morning and get dressed up, you’re probably headed downtown. I doubt he was going to the swamp or any of the mud roads or anything like that. He certainly didn’t look dressed for roadkill collectin’.”

Dewey considered this and seemed to be satisfied that it made some sort of sense, because he never asked any more about it. “So,” he said after a bit, “did your mom really arrest Mr. Garner?”

This question didn’t sit well with me, but I answered the truth. “Yep. Far as I know, he’s still in jail.”

“You don’t sound too happy about it,” he said.

I hesitated. Truth was, I wasn’t happy about it, but I didn’t exactly know why. Something about the whole thing felt very wrong to me. Like there was something I should understand but didn’t, or maybe something I should be remembering but forgot. “Tell me somethin’, Dewey, you were there that afternoon in the rain when we went searching for Mary Ann Dailey. Remember all the stuff Mr. Robert Lee Garner said? Remember the way he talked about Ruby Mae Vickers? How he put flowers out for her?”

Dewey said he did. “He didn’t seem as though he wanted to talk much ’bout them flowers, though.”

I nodded. “But we saw more flowers that day we rode over to his ranch, remember?” I asked. “The day they found Mary Ann? Those flowers seemed fresh to me.”

“Yup,” Dewey said. “Me, too.”

I backpedaled slightly, slowing a bit. “Dewey, do you think Mr. Garner could do something like this to Mary Ann?”

“If the police think so, I don’t see why my opinion would rightly matter. I’m only eleven years old,” he said. This was a slightly different opinion than the one he had expressed the night Mary Ann Dailey showed up dead and Mr. Garner was first taken into custody.

#

There’s a taste of good dialogue in action. It’s not overwhelming the scene by taking up all the space nor is it being squeezed out of existence by exposition. Both have to achieve an equal balance and let the other breathe.

That’s about all I have to say about character voice.

Michael out.

November 15, 2012

Caged!

The new YA book I’m working on is finally into Act II.

The new YA book I’m working on is finally into Act II.

This is the one where I realized I had way too much stuff happening before the story actually took off and didn’t need any of it. Yesterday, I went back and added the parts into the story to make it work and wrote another 5,000 words, bringing everything up to the end of Act I.

It still doesn’t hit Act II until the 12,000 word mark, but I’ll be able to shave some wordage off of that in second draft and, besides, there’s quite a bit of plot going on that’s essential to the story even though we’re not in the “story proper”. It’s not just set up. At least I hope it’s not. Maybe I’m just being self-delusional.

The story is called Caged and is about three kids who get taken aboard a spacecraft against their will and have to find a way to escape. The ship has species from all over the galaxy stowed away in captivity, so it’s sort of like a slave vessel or maybe some sort of research vessel. The kids don’t know. For all they know, they might end up in some cosmic zoo somewhere.

The characters are pretty strong and all bring something different to the table that I can draw on to solve the puzzles that I’ll be throwing at them. My main protagonist, Parker, for reasons he will discover later, is super smart with incredible reflexes. Like better-than-Mensa smart.

His best friend, Braylon, is athletic. Parker is not. Parker can’t even throw a football.

Then there’s Braylon’s girlfriend, Gabriela, who I originally made good at history and geography (which she still is) but all through my writing session yesterday, she kept demanding to be a drama student with an incredible memory for lines from Shakespeare. So I’m not sure when that is going to come in handy, but fate has told me that it will.

I’ve slated the book to come out next summer, probably under DangerBoy Books unless my agent has different ideas for it. The cover is actually already done and looks pretty good. Being almost 13,000 words into it, I’m probably a good fifth or sixth of the way to completion, so I should have no problem getting it ready for a summer release. Especially if I’m doing it Indie style. The first draft will probably be finished before New Years.

That’s it for me. I’m just sitting here in the rain, thinking about aliens.

Michael out.

November 13, 2012

Darkstone WIP Cover Art!

Okay, I wasn’t going to share this, but it’s too cool not to.

Remember, this is really early, so you have to use your imagination a bit.

This is the cover art so far for the Darkstone: The Perfection of Wisdom book. Obviously it’s not done. It still needs a lot of work and, of course, color. But it’s going to look fantastic. The Buddhist mandala in the background is superb. The costume is exactly the way I envisioned it when I was writing the book. I am super happy with how this is progressing. Kudos to my artist, Scott!

It’s a wrap-around cover, so you’re looking at both the front and the back (and the spine). The light will glow from his palm (he has gems embedded in his palms) and grow darker as we get farther from his hand, so I’ll be able to put text over the image on the back of the book.

Now the question is: when will the book be done? I think it’s finished, but I am not happy with the response I am getting from first readers. But then, I haven’t actually had anyone in the demographic it’s written for get back to me with comments yet, so that will be real litmus test. Obviously, I don’t want to rewrite too much because that could change the spine size which might impact the artwork. Ug.

The inside of the book looks nice. I’ve used dropped caps on chapter starts and taken the center circle from the cover art mandala and put it behind the chapter number which is lowered on recto pages. I’m using a nice font, too, with a good size and a nice line spacing.

In other words, if people would just come back and say they love the damn thing, it’s pretty much ready to be printed other than the cover art and one final proofread (it’s even been copyedited–sigh).

Oh well, such is life.

Michael out.

Lions, Tigers, Bears, New Proposals, Oh My!

My two proposals for the next books I want to write are finally in the hands of my editor.

Cry and the Blessed Shall Sing

The first is a sequel to my upcoming release Dream with Little Angels. It’s called Cry and the Blessed Shall Sing and has two main plot lines running through it.

The first is a sequel to my upcoming release Dream with Little Angels. It’s called Cry and the Blessed Shall Sing and has two main plot lines running through it.

One, of course, is the main mystery component of the book which circles around a twenty-two year old woman named Sylvie Carson who has a newborn baby. Sylvie’s boyfriend, the father of the baby, left her alone six months before the birth. The woman suffers from post dramatic stress disorder from an event that happened in her childhood; she witnessed her younger brother being shot in cold blood by a preacher right in front of her at the dinner table while her family sat down to eat. Because of her illness, she is a target for abuse and not taken seriously by the police until tension begins to ramp up. In the process, Sylvie learns things about her past and about her brother and now dead parents that she never knew before.

The second plot line is about our protagonist, young Abe Teal (now twelve years old) learning about his pa’s side of the family–an aunt and a grandma and grandpa he never knew he had. This plot line mirrors the first in a way, as they are both about finding family and discovering where you come from.

The theme of the book is finding your roots and, at the same time, finding forgiveness. For Sylvie, this means discovering truths about her family and forgiving the preacher who killed her baby brother. For Abe, it means learning about the relatives he never knew he had. For Abe’s mother, Leah Teal, it means finally forgiving her husband, Billy, for dying in a car crash and leaving her all alone to raise two children when Abe was only two and his sister just five.

All Abe’s parts in the book are written from first person point of view. Otherwise, it’s in third person. There won’t be a lot of different third person character shifts. Probably three or four maximum.

That’s about all I can give you without completely giving away the story. It’s tight. The outline is pretty complete. The first five chapters are done, and I’m really happy with how the writing is coming along.

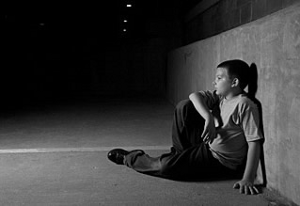

Boy, Alone

The second proposal is for a completely different book. I mean, of course it’s a different book, but it’s different in every way imaginable. Boy, Alone is written in journal format, following the same structure I used in my award-winning short story My Lame Summer Journal by Brandon Harris, Grade 7. In fact, it starts with the same premise: the protagonist is given a school project over summer break: to keep a journal.

The second proposal is for a completely different book. I mean, of course it’s a different book, but it’s different in every way imaginable. Boy, Alone is written in journal format, following the same structure I used in my award-winning short story My Lame Summer Journal by Brandon Harris, Grade 7. In fact, it starts with the same premise: the protagonist is given a school project over summer break: to keep a journal.

It is there that this novel and my short story begin to diverge quickly, however. Boy is targeted at a much more adult level. The protagonist, fourteen-year-old Jason Tillman, lives in a rundown apartment outside of Seattle with his mom and her drug addicted boyfriend (Rick, which, as Jason is quick to point out, conveniently rhymes with “prick”).

The journal entries start out innocuously enough, but quickly turn dark when Jason begins to earn the trust of the teacher he’s writing the journal for, a Mr. Henderson. The students were told they could write anything they wanted and wouldn’t be reprimanded. It takes some time before Jason comes to accept this. But soon, the journal becomes his security blanket and he’s revealing his innermost secrets.

We learn about his crush on a certain girl at school. We learn how he’s treated by other kids.

And we learn that his mom also has a drug problem. And the drug problem she shares with her boyfriend is a constant source of contention in the apartment.

When Rick’s not high, he’s mad about something. Jason asks his mom why she doesn’t leave. She says she’s happy. She says, “At least he doesn’t hit me.” She tells Jason if Rick ever did hit her, that would be it.

And that’s when the story takes off. When Rick finally snaps one day and gets violent.

Jason’s mom picks him up from school and the two flee to Canada where she has a friend they can stay with. She tells him things are going to be different from now on. She’s going to quit the drugs and settle down. They’ll have a proper life.

Then, after a long struggle, it looks like everything actually is going well. That’s when, right out of the blue, something slams into their life that neither of them ever had a chance to see coming.

Boy, Alone could be the most tragic and heart-breaking story I’ve ever come up with. Yet, at the same time, there is some humor woven through it, and, in the end, there’s a glimpse into the human spirit that shows the power and courage we all possess to go on even when the odds are stacked horribly against us.

Anyway, those are my two newest novel proposals. Fingers are crossed that I’ll be finishing them soon. I’m really excited by the work done so far on both. I think it’s some of the best writing I’ve ever done. I hope that makes me sound more proud than egotistical.

Michael out.

November 11, 2012

It’s Not The Quality, it’s the Quantity

Someone from my writing group recently asked me to look over the beginning of their manuscript and give my opinion as to whether or not the story was “working”. They are nearing the end and, as most writers know, the end of a story is very much tied to the beginning. If your ending doesn’t work, it usually means there’s something wrong with your beginning or vice versa.

Someone from my writing group recently asked me to look over the beginning of their manuscript and give my opinion as to whether or not the story was “working”. They are nearing the end and, as most writers know, the end of a story is very much tied to the beginning. If your ending doesn’t work, it usually means there’s something wrong with your beginning or vice versa.

Beginnings are vitally important to stories because they set up something called Author/Reader Trust. It’s in those first twenty pages or so that you, the author, convince the reader that you’re capable of being trusted to take him on a three or four hundred page journey and that it will be satisfying in “expected” ways.

Am I implying that this Trust thing means you have follow some sort of pattern and make sure nothing surprising happens?

Not at all. What I am saying is that the reader is trusting you not to use your power as a writer in ways that behave beyond certain contracted guidelines. Guidelines that are unwritten but come into existence very early on in the reading experience.

Let me give you an example.

I love Quentin Tarantino movies. Always have. I also really like Robert Rodriguez movies. So, it was with great anticipation that I went to see From Dusk Till Dawn.

Now, I have a weird rule when it comes to movies: I try desperately to avoid any advertisements, trailers, commercials, reviews. . . absolutely anything that will tell me anything about the movie before I go. I just feel they give too much away. I like to go in blind. In a perfect world, I would rather not even know the title. Especially if it’s something cool like a new Tarantino film.

So, in hindsight, really I got what I deserved. But let me continue.

Another weird thing with me is that I absolutely detest vampire movies (Buffy excluded). They just don’t click with me. I find them far-fetched and almost laughable. I would never knowingly go see one. I spent ten minutes in Interview With a Vampire before I got up and left the cinema.

Do you see where I’m going with this yet?

So I sit down with my super-sized popcorn and giant Diet Coke trying to avert my eyes from the trailers before the movie, anxiously awaiting the next Tarantino masterpiece and it opens on that gas station out in the desert (if you haven’t seen it. . . the movie’s worth seeing, just for the opening sequence. Even if you hate vampires). And I’m watching and waiting for the cool Tarantino spin, because you just know it’s gonna be there.

And of course it is. They come out of the washroom with the hostage and I’m on the edge of my seat. This movie rocks. This movie is great. This is the best movie ever.

It stayed the best movie ever for another fifteen minutes. Tarantino had me. In my mind, in those fifteen minutes, we had formed a contract: he was going to give me a movie full of surprises with guns and chicks and cars and violence and it wasn’t going to slow down until the clock finally hit that hundred and five minute mark.

Well it sure turned out to be full of surprises. Not good ones, though. Not for me, at least.

When they’re in the bar and suddenly that girl jumps on the table and flashes the fangs and tears open that guy’s neck, I was like: “What just happened? That can’t happen. We had a deal. Vampires weren’t part of the deal.”

I felt gypped.

Everyone else in the theatre loved it. Of course, everyone else watched reviews, commercials, trailers, and ads like normal people.

Anyway, books are like this. You make a deal with your reader that you are going to give them a fair shake. If you’re going to tear the throat out of a girl’s neck at the top of Act II, you better have a vamp on your cover or some indication that it might be coming up in your opening twenty pages, or you’re going to lose your audience.

If Arnold Schwarzenegger dropped out of a helicopter with a machine gun in the middle of Steel Magnolias and started gunning down everyone over seventy, people would feel let down by the writers of the movie. But if Arnold had appeared in the first five minutes and shown to be back from the war with a piece of artillery in his head and unbalanced and had somehow gained possession of UH-60 Black Hawk, it may have actually worked. It wouldn’t have broken the audience contract at any rate.

So, getting back to the manuscript I reviewed. The ending isn’t finished yet, but the writer is close enough that I can see where it’s headed. There’s some good writing in this book. It’s got some great scenes that rise in tension and it’s an adventure mystery book that manages to continually push the plot forward.

All this is fantastic.

Having read the beginning, though, I found some problems. And they are common problems I think everyone encounters.

One has to do with the contact with the reader, which right now remains undefined because I can’t tell what it is. There is one scene of action but it’s fully encapsulated, meaning it can stand-alone by itself. It doesn’t have any ramifications outside of the beginning of the story. This may be interesting, but it doesn’t give the story anywhere to move from.

There’s also either no inciting event or the inciting event is pushed so far back I hadn’t got to it yet after reading the first two chapters. This is a YA book so it’s shorter than a regular novel. YA books are fun to write because they’re short. They’re like mini-novels, but with YA it’s even more vital that you get to the inciting event as quickly as possible. You haven’t got time to walk the reader to the story.

Now this is in no way a slam to the writer in question because everyone walks the reader to the story on their first drafts. And I mean everyone. I do it all the time and don’t even realize I’m doing it (isn’t it funny how we can see things in other people’s work so much easier than our own?). I only recently figured out that the new YA title I’m working on has three entire chapters that happen before the inciting event that aren’t just in the wrong spot. . . I don’t think they’re even needed! That’s like fifty pages.

You’re story doesn’t start until your inciting event happens, so I was going to have the reader go through fifty pages plus my setup before my story even started. Well you know what? That book would never get published. And I didn’t even notice it until I woke up one morning and it just occurred to me that it was all messed up.

So, if you can’t see these problems in your own work, how do you ever get to the point where you’re improving as a writer? Do you have to rely on other people to critique you?

Other people’s critiques are good, especially when you’re starting out, but you can’t rely on them. You have to develop some sort of intuitive instinct that tells you when you’re writing crap and when you’re writing quality. It won’t always be right, but you can sharpen it, like any other skill. And the way you sharpen it is with practice.

How do you practice? You write. Like anything else, the more you write, the better you get.

When I reported back to my writing group friend with what I thought of the beginning of their story they told me I am very good at this. My response was that I’m not so good as I’ve had a lot of practice. I was very lucky early on in my career to meet Dean Wesley Smith and Kristine Kathryn Rusch. They became my mentors and I spent many weeks at their house down on the beach in Oregon in very intense writing workshops.

They taught me not to love my work and not to be afraid to throw things

out; they drilled into my head that at least eighty percent of what I write is going to be crap. And you have to learn to be able to tell the difference because you can’t rely on other people to tell you. No offense to mine if she reads this (because mine is actually pretty good) but as a general rule: agents are useless. Editors are useless. Time and time again, you hear of books like Harry Potter that get turned down by twenty-eight literary houses or something like that before going on to outsell the Bible.

And the industry is completely flaky right now and getting flakier all the time. Agents are supposed to be working for the author. All money should flow to the author (this was the Gospel according to Dean–I believe he’s an advocate of self-publishing right now, so his stance on how money flows may have changed a bit, it’s been a while since we talked), but when you talk to the people in New York, you would think, given the balance of power between agents and writers, that writers work for agents. It’s crazy. Again, I want to point out that there are exceptions. If you get a good agent, consider yourself blessed. I do.

The best thing you can do is control the things you have control of, and the main thing you have control of is the writing. Get good at it. Dean and Kris (Dean in particular) taught that the best way to get good at writing was to write as fast as possible and to put out as much product as possible. Don’t worry about quality because quality has nothing at all to do with how much time you spend on a book. I’ve written sixteen novels. Some really suck. Some, I think, are far better than the one I have being published (although they are part of my earlier oeuvre and probably appeal to a less diversified audience–I was a bit odd back then with what I wrote. It didn’t pigeonhole well). For two years running, I managed to write a million words. That’s two million words in two years. I’m not awfully good, I’ve just written two million words in two years. You can’t help but know what you’re doing if you put up those kinds of numbers.

These days, I don’t hit anywhere near those totals. I like to write two

adult novels and three YA books a year and maybe four or five short

stories. I’ll probably also outline a few things and tinker with some

other things. But I don’t try to knock myself out. I took a hiatus from

writing for three years. Ironically, it was during that hiatus that my

agent sold my book (it wasn’t quite a hiatus… I did write a few things, but from the output I was experiencing I was definitely considering it a hiatus).

Anyway, the point of this story is that writing is a very harsh

mistress and it can be the most disheartening thing in the world. And I

know as much as anyone that it’s very hard to remind yourself of things

when the darkness comes swooping in, but if you can, try to remember

that there are no wasted words. Every single keystroke you type is

important and teaching you something.

And writing is like anything. The more you do it, the better you get. Sure, some people are born better than others–Stephen King probably has an innate talent that allowed him to start at a level I will never hope to reach, but the nice thing about writing is that I just might. I could. Possibly. Because it’s not an art. It’s a craft.

And it’s fine to learn about grammar and usage. In fact, if you’re an Indie publisher, it may be vital if you’re doing your own copyediting. But you can’t be thinking about those things when you write your first drafts. You can’t think about usage. You can’t think about grammar. You can’t think about structure, even (you can before you start, though, and it might do you well to do just that). For me, the key is, when I’m writing, I don’t think about anything. My head just goes into that far away place and I listen to my characters and try to keep up while they talk to me.

That’s when it’s good. When things are great, I just type until four in

the morning and have no idea what the next line of text is going to be

or what’s going to happen next.

Then there’s those times when it’s bad. When it’s bad. . .

Well, I may as well go do the dishes because I tend to write one line

of prose every hour and it sucks hind you-know-what because the left

side of my brain refuses to let go and just let the right side do what

it’s meant to do. That’s probably the biggest value I got from writing

a million words in one year: the ability to just shut off the analytical part of my brain and not care what comes out of my fingers.

Read the books on structure and grammar and usage and story construction and then forget it all. Your subconscious will absorb it. Let the right side of your brain sop it up so that it can deal with it in its own way while the left side goes to sleep.

Relax.

Trust the process. The process works. As long as you’ve gotten to a certain level of quality, that is. In the beginning, you can’t just shut everything off. You do need to do some work. But it doesn’t take long to get to the point where you’re writing decent prose. You’ll know when you’re there. Nobody else can tell you.

It’s something you feel in your gut.

Michael out.

Michael Hiebert's Blog

- Michael Hiebert's profile

- 99 followers