Christopher Meeks's Blog, page 4

February 25, 2015

3 Surefire Tips to be a Great Writer (A Video)

I tried something new a little over a year ago: teaching online. I live and write in California, but agreed to teach creative writing at Southern New Hampshire University via the internet. All started well. My first two classes were great with a dozen interesting and eager students in each class, and I had some latitude in how to teach.

To teach online well requires more time than physical classes. It's because you can't see your students' body language or answer things quickly. Most things are written. When SNHU doubled my class size for the third term--to 25 students--and I was forced to give some other professor's writing exercises and readings, which was a lot of busy work for the students and me, it all became crazy. I won't go into it, but I didn't agree to do it again. Even so, I liked the students a lot. I even liked the medium. If you're looking for online classes in writing, look for small classes such as at UCLA Extension.

One thing I wished to try for the third class was to be more visual. I created small videos for my class, which worked out well.

This led to another type of video, one for the general public on how to make it big in writing: getting rich-rich-rich from your efforts. After all, that's what I'm often asked: How do you get rich in writing? I answer it here. Click below for my surefire tips to get there. It’s short, just four-and-a-half minutes.

To teach online well requires more time than physical classes. It's because you can't see your students' body language or answer things quickly. Most things are written. When SNHU doubled my class size for the third term--to 25 students--and I was forced to give some other professor's writing exercises and readings, which was a lot of busy work for the students and me, it all became crazy. I won't go into it, but I didn't agree to do it again. Even so, I liked the students a lot. I even liked the medium. If you're looking for online classes in writing, look for small classes such as at UCLA Extension.

One thing I wished to try for the third class was to be more visual. I created small videos for my class, which worked out well.

This led to another type of video, one for the general public on how to make it big in writing: getting rich-rich-rich from your efforts. After all, that's what I'm often asked: How do you get rich in writing? I answer it here. Click below for my surefire tips to get there. It’s short, just four-and-a-half minutes.

Published on February 25, 2015 11:48

February 20, 2015

AUTHOR STEPHEN KING – And Things I've Learned

When I first started writing, I aimed to be a “serious young writer,” which is why after working as a stock clerk at a Hollywood camera store and then as a tile salesman in Los Angeles’ San Fernando Valley, I joined an MFA writing program at USC.

I adored my time at the university and made good friends. We were all serious young writers, ready to storm the Bastille of Mediocrity, beat aside bad agents, and deliver the Truth. Some of us were there to write the serious and artful Great American Screenplay along the lines of Five Easy Pieces, M*A*S*H, The Deer Hunter, and The Conversation. Others, who cared nothing for money, wanted to write the next great play, our generation’s Death of a Salesman or Who’s Afraid of Virginia Wolff? I would later write Who Lives?, a story about who might be among the ten test subjects of the first working kidney dialysis machine.

Some of my friends wanted to crack the novel in a fresh way, such as was done with Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, and whatever Tom Wolfe was doing with New Journalism, which seemed novelistic. Witness The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.

Me, I wanted to write movies, plays, and novels—and throw in short stories and essays. The great thing when you’re young is you don’t have to put a governor on your ambitions.

None of us in the program were short of dreaming. The one thing we did NOT want to do was write in a genre, such as writing horror or a thriller. Genre was selling out—just not dreaming big enough.

Influential books at the time for me included Watership Down by Richard Adams, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance by Robert Persig, and Sophie’s Choice by William Styron. I didn’t read Stephen King’s books of that decade, which included Carrie, The Shining, Salem’s Lot, and The Dead Zone. That’s because Stephen King was in the horror category, a genre I didn’t want to consider. I also assumed (wrongly) that King must not be a very good writer if he was always writing horror.

Then a few years ago, I read some of his short stories including the one that became the movie The Shawshank Redemption. The stories, touching, revealing, full of emotion, and well-written, blew me away. When his book 11/22/63 came out, I had to see his take on the Kennedy assassination because I remembered the day vividly. I was in fifth grade when Kennedy died. I saw all the adults around me cry, and my parents were Republican.

I became glued to King's 11/22/63. After I finished it, I moved onto his Joyland. I found it gripping and emotional.

These two novels made me appreciate King’s writing and also see many of the things he probably learned early on, things which have taken me many years of writing plays, screenplays, and novels to see. Because I also teach creative writing, these are some of the lessons I try to get across to my students.

I should explain both novels briefly. In 11/22/63, 35-year-old English teacher Jake Epping learns that his friend’s diner in Maine has a time portal in the back room that takes any traveler to a date in 1958 at that same place. No matter how long you stay away, you return two minutes after you left. After Epping tries it a few times, he realizes he could drive down to Texas, hang around five years, and then try to stop Lee Harvey Oswald from killing JFK.

Joyland is both coming-of-age and a mystery set in 1973. Twenty-one-year-old Devin Jones's heart is broken by his college girlfriend, who runs off with another guy. Each day, Devin is consumed by the loss, but after he takes a summer job at an amusement park in North Carolina and comes to know his co-workers, he slowly mends. He also gets curious about a murder that happened in the park a few years earlier, and there's a rumor that her ghost can be seen on one of the rides.

Using Joyland and 11/22/63, I offer a few things I’ve come to appreciate about King’s writing.

1) Devin Jones in Joyland and Jake Epping in 11/22/63 are great protagonists. Jones is vulnerable and temporarily damaged—and I deeply empathized with him. Epping not only has tremendous curiosity for when he finds a wormhole into the past, but also he realizes he can expunge one great evil—Oswald—and perhaps change history for the better. Both these characters are driven, and readers clearly see their goals and desires.

2) Truth. One of my own goals in my work is to meter out truthful moments. I’m not so much going after the Big T Truth, but it’s the little ones that count, moments that reveal life as we know it. King does this as easily as breathing.

For instance, in Joyland, Jones says, “People think first love is sweet, and never sweeter than when that first bond snaps. You've heard a thousand pop and country songs that prove the point; some fool got his heart broke. Yet that first broken heart is always the most painful, the slowest to mend, and leaves the most visible scar. What's so sweet about that?”

Later Jones realizes, “It’s hard to let go. Even when what you’re holding onto is full of thorns, it’s hard to let go. Maybe especially then.”

In 11/22/63, Epping says, “We never know which lives we influence, or when, or why.” Later he adds, “Stupidity is one of the two things we see most clearly in retrospect. The other is missed chances.” We also come to learn and understand another truth, “The past is obdurate.”

When I write, I’m on the lookout for moments when such truths can lend the story extra depth.

3) Foreshadowing is hard to do, but when done well, it gives any story a sense of destiny and the tone of “This happened; you have to hear this.” One reason it’s difficult to create foreshadowing is that you have to know your own story well. If you’re on a first draft, you may not know what will happen fully. You can’t foreshadow it yet. Thus, foreshadowing is something I tend to add in later drafts.

In both of King’s books, the foreshadowing lends foreboding. Also, the narrator indicates he’s older than the events, and he’s relating what has come to dominate his memory. This gives a sense of importance to the stories.

4) Dialogue and details. King has the right balance for both—not too much or too little, which sets the pacing. “I started to reply,” says Jones about the fortuneteller. “She hushed me with a wave of her ring-heavy hand.”

5) The biggest thing that originally stood in my way of appreciating genre fiction was the idea that genre was devoid of theme. Perhaps I thought that literary stories considered theme and all other stories didn’t. Theme, however, is everywhere. Even writers who don’t think about theme tend to have one because where a story ends says something. You can have the richest, most empathetic characters, but if in the end they are all brutally murdered, that’s suggesting something about life, no?

I never thought of Raymond Chandler as genre because the plots of his detective stories were all over the map—but Philip Marlowe’s insights, tone, and themes grabbed me. That should have clued me in that genre could be special.

My wife tends to watch what I call “bludgeoning shows,” things like Dateline or 20/20 where the true-life tales are often about one spouse murdering another and then trying to hide it. A theme that comes through is “Spouses lie and murder, and marriages are horror shows.” While that’s certainly a truth out there, it’s not one I want as universal or paramount.

Theme at its best is a truth that weaves through a story and can be sensed in the end. Good writers somewhere along the way come to understand what their stories are about and then make readers or viewers discover it on their own. King is a master of this. In both Joyland and 11/22/63, you’re in good hands.

I'm now a King fan, even if I haven’t read most of his books. I love these two and I’m starting a new one, Lisey’s Story, because he said in an interview, he felt it was his best one. Truth be told, now that I’ve written two crime novels, Blood Drama and A Death in Vegas, I have an extra appreciation of genre. In theme, I’ve strived to make the books more than bludgeoning shows. They are about the human condition, including its joys and absurdities.

Good stories are hard to create, and as a writer, I have to celebrate good ones when I see them. In my off hours, I’m enjoying Bosch , which streams on Amazon. There’s another genre writer I enjoy: Michael Connelly. That’s for another blog.

--

Note: NPR interviewed King about how he writes. Read/hear that interview by clicking here.

Published on February 20, 2015 08:37

February 18, 2015

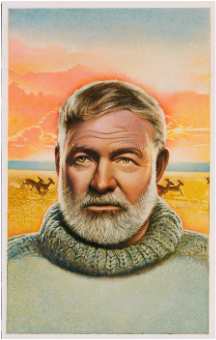

“Why Can’t Jake Barnes Have Sex?” and Other Pressing Questions in Reading

Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Hemingway When I took my first creative writing class, a poetry class, in college at the University of Denver, I did it because I needed to fill in some credit hours. English had never topped my hit parade because most of my professors had made me feel that to truly understand a book, you needed to be an English major. I was not. I was into psychology. Little did I know then that psychology would be important in reading and writing.

My last required English class, one in American Literature, turned me around. I couldn’t believe that in Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, the protagonist, Jake Barnes, was impotent—although I didn’t know that word then. I surmised, though, that his penis somehow didn’t work right, and could we really be reading about this in a class? Was it legal for a writer to write about that? How were we going to talk about it?

I learned that Hemingway had traveled to Spain in 1925, and a lot of those experiences such as the running of the bulls had ended up in his book. He’d had a few wives, so apparently impotence wasn’t a problem. Maybe it was when he killed himself on July 2, 1961.

After that, I also discovered that an F. Scott Fitzgerald story that we read, “The Rough Crossing,” was based on a trip that Fitzgerald and his wife Zelda had taken. I hadn’t known until then that it wasn’t cheating for writers to draw from their lives so directly. Also in “The Rough Crossing,” I was impressed how the storm at sea matched the storm in the characters’ marriage. That was a clever thing.

When I took the poetry writing class, I drew from my life, as did many of the other writers in the class, and it was fun. Symbols emerged in some of the poems, which could add extra meaning. I learned of other poetic devices, such as alliteration and onomatopoeia. This word stuff was amazing.

Another important event in my life was that I spent part of my junior year abroad in Denmark. I learned about language in a whole new way: if you don’t know a language, it’s difficult to communicate. In high school, I’d taken Spanish and Latin, but because Minnesota didn’t have many people speaking either language, I never felt any urgency to learn. In Denmark, I really wanted to understand what people were saying around me.

I took Danish, and I came to see that understanding another language also gives you clues to how a large group of people think. After all, language guides our thinking. Danes have some dozen words for “snow,” yet they have the same word for “fun” and “funny,” which to us are two different concepts. There, I also spent a lot of time reading English-language novels that I picked up in a local library because I had a lot of time to myself. I’d never been much of a reader until that point. Books were incredible. How had I missed that before?

I’d discovered Kurt Vonnegut’s books in Denmark, and while the story lines were wild and of science fiction, much truth rang out to me. In Cat’s Cradle , for instance, Vonnegut created words for things that had no previous words. A “karass” is group of people linked in a cosmically significant manner, such as those in a Corvette-owners club. A “duprass” is a karass of two: two people who are so deeply connected, they are their own universe. They often die within a week of each other.

I read voraciously abroad. I remember looking for the thickest book in English at the Danish library. It was Of Human Bondage by Somerset Maugham. I read it on buses, trains, everywhere. Wow.

After college and a few years of jobs selling things such as men’s clothes, cameras, and ceramic tile, I went on to earn an MFA in creative writing. In 1994, I started teaching creative writing at CalArts after I’d been publishing a lot of articles and reviews and writing short stories and plays.

One thing most creative writing classes don’t have time for is reading published stories and books. Nonetheless, I would slip in a few. Why reinvent the wheel when writers before us have done some amazing things? Reading great stories gives you permission to experiment.

In my third year of teaching, the chair of the English department at Santa Monica College called me out of the blue, having heard I was an inspirational instructor, and she asked had I considered teaching English? I hadn’t, but I took up her offer. My challenge was, “How do I stir my future students in English a way that most of my English professors had not?”

The main thing that had turned me off was in reading older books about older characters that I had no connection to. I thought I’d use contemporary nonfiction narratives and novels, trying new things every semester, one by a female author, one by a male, to keep me on my toes. It has worked. I assign the reading and a few questions to go with it, and my students and I sit in a giant circle and discuss it, like a book club. Everyone talks.

I also instruct them how to read more actively. Reading with a pen in hand helps. They should underline or highlight things that speak to them. If they have a question about something, write it in the margin. The first time a major character is introduced, put a bracket around it. For example, J.K. Rowling in the first Harry Potter book introduces Hagrid with “hands the size of trashcan lids” and feet “like baby dolphins.” When you write in your book, you interact with it. You make it your own. If it’s your book, you can write in it.

I delight when students—and it happens often—say something like, “I’ve never been a reader, and I didn’t think I’d like reading this, but I couldn’t put it down.” One student told me, “It’s weird. It’s like a movie in my mind. I’m looking at ink on a page, and suddenly I’m in these people’s lives. I love it.”

I’ve used such books as Patti Smith’s Just Kids, about her years after high school in New York, and she and Robert Mapplethorpe struggled to find what to do with their lives. Novels such as In the Lake of the Woods by Tim O’Brien and Margaret Atwood’s Oryx and Crake worked well. Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five had only a lukewarm response, but his Cat’s Cradle found converts.

I’ve ended up creating a list on Amazon’s Listmania of the most successful books I’ve used, which you can see by clicking here. These are books that engaged nonreaders, and you may enjoy them too.

Many of my students are surprised they like reading and want to know how to find more books. With perhaps two million books published each year, there absolutely are new things you will love. You just have to find them. Services such as BookBub, BookGorilla, and BookBlast help you discover new books at bargain prices. They send you a handful of links to highly rated books each day whose eBooks are on sale. Choose the category of books you like, and in this daily email, you are likely to find things that grab you.

I know I’ve ignited a number of students into reading. Reading helps a person think, feel, and see the world in fresh ways. It may inspire you to write, and writing draws you into thinking and understanding more deeply.

May you find the frenzy of reading. Reading is life.

Published on February 18, 2015 14:40

February 16, 2015

The Planet-Moon of Being a Writer

When I was ten, my parents gave me a telescope, and I formed an astronomy club.

Suburban Minneapolis had the benefit of many stars. As my four friends and I met one evening at sunset, ready for the blanket of stars, the full moon slipped up over the horizon and surprised us. The huge dish radiated bigness—bigger than the moon was normally—and one of us said, “Hey, it’s Mars, and it’s off its course. What if it crashes into us?”

We were convinced Mars had slipped out of line, and no one but us knew about it. We hopped on our bikes and rode toward this orb quickly as if we could get closer and examine it better. We pointed skyward. “Mars! It’s definitely Mars!”

This moment hangs as a symbol to me of what it is to be a writer today. One is that there are many misguided things to do that suck up your time, money, and attention. The second is that marketing definitely has its own gravity and is a giant moon in your life.

One of the joys of taking a creative writing class in college or elsewhere is that you’re focused on the creative process, not on marketing. You are building your skills. At that point, commerce may as well be Santa Claus—it doesn’t seem real and, if anything, will bring you the gift of a career. Don’t count on it. Readers search for great stories told well. They have to find your work, though, and that takes marketing. You need it.

Today’s writers, if they aim for sales, have to become practical and put aside the “fun, creative part” to promote what they have. What follows are some truths I’ve learned about the planet of creativity in harmony with the moon of marketing.

1) Don’t rush into marketing less-than-polished work. Everyone and her taxi driver are writing books. If you truly think your book has a place in the marketplace, engage your talented friends or hire a professional editor to get your book to be the best.

2) Book publishing is intimidating. That’s why agents and big publishers still exist—because if you’re talented, and you want to stay focused more on the writing than on the marketing, this traditional route still works. To get an agent requires writing a query letter—which has to be some of the best writing of your life. After all, you’re proving your worth in a page.

3) If you go the self-published route, know in advance that you have to become a master of marketing. You can hire services or people to help you with the self-publishing process, but beware of services that promise you the moon. You can spend thousands of dollars to little effect. If you didn’t seriously take my first point, polishing your work, no one is going to buy your book. An amateurish book design or less-than-stellar book description will hobble your book more.

4) Self-publishing can work. It takes dedication, starting with polishing your book. You learn that self-promotion isn’t singing “Buy my book” in a loud voice on social media, but rather, you do a lot of indirect things, such as joining the community of writers by writing a blog, writing book reviews, advertising, hiring a blog tour operator, and more. It’s all ever-changing, so keep reading about this stuff. The fact you’re reading this is a good sign.

5) The challenge of marketing can be addicting. It’s fun to watch something that you did sell a thousand books in a day. Don’t let it override your main goal, which is to write books with merit.

6) One less-obvious step to get you thinking and immersed in marketing is to attend a writing conference. To get a taste of one, see my previous post or click here.

May your planet and moon circle with success.

Published on February 16, 2015 12:11

February 15, 2015

RICK BASS: Highlight from the 2014 AWP Conference

Writers often tend to keep to themselves, but the biggest convention of writers is the annual AWP Conference--the Association of Writers and Writing Programs--which will take place April 8-11 this year in Minneapolis. I thought I'd offer this from last year's conference to give you a taste.

--

Imagine a three-day film festival in a giant complex where you had a selection of 33 movies every 90 minutes, and each of the 500 movies would be shown only once. Add to that more than 12,000 attendees vying for the choices over the three days. That gives you an inkling of what it felt like to attend the 2014 Conference for the Association of Writers and Writing Programs (AWP), held in 2014 in Seattle.

Attendees received a thick catalog detailing the more than five hundred panels, and panels changed every 90 minutes. The panels could be divided into categories. There were those that addressed publishing and getting published, either through traditional methods or other ways such as do-it-yourself. There were panels that addressed ways of teaching creative writing, such as using the stories of Flannery O’Connor in the classroom.

Then there were voyages of how to write creatively, such as research strategies for creative nonfiction or using an unusual point of view such as from a dog. Academic explorations examined such things as passive characters in contemporary fiction and poetry as a philosophical foray. Last, there were readings of poetry and fiction.

If a person could absorb two or three panels a day, catch a reading, meet a friend for lunch, and attend the Book Fair on the fourth floor of the Seattle Convention Center, that was a big day. The Book Fair featured more than 600 exhibitors competing for your attention, offering handouts, chocolates, raffles, and glimmers of publication. One could meet editors of journals for future submissions or examine some of the more than 200 MFA writing programs across the country.

Then there were the hundreds of off-site meetings and parties. To zoom from 9 a.m. to 11 p.m. each day took much stamina. To find a moment of rest and pleasure was difficult—until I found that short story writer Rick Bass, who lives in Montana, would be reading his stories, accompanied by live music. The band Stellarondo, named for the character in Eudora Welty’s “Why I Live at the P.O.”, had composed original scores to go with Bass’s stories.

The AWP Convention, by the way, is the only convention I’ve liked. Years ago, I’d been to a few Comdex computer conventions in Las Vegas—miles of walking indoors to see the latest programs, computers, and gadgets. I’d been a delegate to the Modern Language Association, but would be lucky to find three panels among its hundreds of offerings, most of them professors dryly reading papers to other professors.

I arrived for Rick Bass at 10:30 a.m. to a giant ballroom filled with chairs and a stage up front, to find only twenty people, and the band was just setting up. I went up to one person and said, “This is all there is? I thought this would be the coolest thing at the whole convention.”

“Me, too,” she said. “I don’t get why it hasn’t started yet or why more people aren’t here.”

I went up to a band member to learn the show was at noon. We’d misread the catalog. Thus, I grabbed a cab to the waterfront to visit the Seattle Mystery Bookshop on Cherry Street, then zipped back in time to see the performance.

Rick Bass sat in a comfortable chair on stage that had a microphone. The band spread out to the right of the stage, and the four members prepared their instruments: pedal steel guitar, acoustic and electric guitars, banjo, cello, glockenspiel, musical saw, upright bass, and vibraphone. The lights dimmed, and the magic began, first with the band playing what might be called mood music, and then Rick Bass starting in on his story “The Canoeists.”

While I instantly loved the idea of music and words, one thing worried me: that the music might overwhelm the stories. Instead, the music offered a gentle flow, allowing Bass to pause at certain sections, and he didn’t have to start up right away. The music filled the space and let you think about the words you just heard. At times, the band members would take turns playing, so that there would only be one soothing sonic sense at a time. Together, they mingled in harmony.

After the first story, Bass told the audience that he had had doubts when the band first suggested a collaboration. He pictured beat poets with bongos, and he said that had rarely been effective. “However, working with these musicians,” said Bass, “I learned what Barry Lopez meant about ‘stories need to have space.’” Now when Bass writes, he pictures the aural space his words might have.

I sat in the front row and let the music and words drift over me, and everything was about the story. I was in the moment as when I ski. I was present. It was now. Each story unfolded at its own pace. Bass read two more stories, “Fish Story” and “The Bear.” When it was over and the lights came up, the woman next to me and I looked at each other and said “Wow” in tandem.

To get a taste of Bass with music, the band has clips on its website, which you can hear by clicking here. After the show, they were selling CDs of Bass’s stories with music, but the line became quickly long, and I had to get to the airport. Still, the show was the perfect way to end AWP. I’ve since learned one can get the album here.

Published on February 15, 2015 13:03

March 3, 2014

RICK BASS: Highlight from the AWP Conference 2014

Published on March 03, 2014 15:03

March 1, 2014

AWP: A Good Publisher is Hard to Find

Published on March 01, 2014 00:00

February 18, 2014

The Planet-Moon of Being a Writer

Published on February 18, 2014 12:28

February 16, 2014

Sting and Paul Simon in Los Angeles Last Night

Published on February 16, 2014 18:48

Reading for Your Life

"Outside of a dog, a book is man's best friend. Inside of a dog it's too dark to read." -- Groucho Marx

Published on February 16, 2014 18:24