Stephanie Morrill's Blog, page 9

March 5, 2018

The Newbie's Guide To Writing Historical Fiction

Stephanie Morrill is the creator of GoTeenWriters.com and the author of several young adult novels, including the historical mystery, The Lost Girl of Astor Street (Blink/HarperCollins). Despite loving cloche hats and drop-waist dresses, Stephanie would have been a terrible flapper because she can’t do the Charleston and looks awful with bobbed hair. She and her near-constant ponytail live in Kansas City with her husband and three kids. You can connect with her on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, Instagram, and sign up for free books on her author website.

Once I've written two to three chapters, I have more of a feel for who my characters are and how the story should unfold. This is when I set aside what I've written, open a Word doc, and begin my synopsis.

Over the course of my 10 years of writing professionally, I have gone from haaaaaaating synopses to now rejoicing when it's time to write one. I wrote two blog posts about my process for them last year, so I won't repeat that, I'll just link to them:

How to Write a Synopsis for Your NovelHow to Edit a Synopsis for Your Novel

And then Shan wrote a post about how she uses her synopsis as an outline. That's a good one too.

As a historical writer, once I see my synopsis, I have an even better idea of what kind of research I may need to do ahead of time.

For example, for Within These Lines , I knew a character would be shipping out with the navy and getting taken prisoner, so I needed to research possibilities for that in order to build my timeline correctly. I also knew that my climax surrounded a historical event in the concentration camp, so I spent time researching that as well.

More research topics always crop up as I get into the first draft, but the synopsis helps me to take care of a few ahead of time.

Lastly, if you write historical or historically-inspired fiction, I have written an ebook that I'm giving away for free to those who are email subscribers!

When I decided to write historical fiction, I was lucky enough to have a seasoned historical fiction author as my best friend. I wrote this ebook to help guide those who don't have that advantage! If you're not already signed up to receive my author emails, you can do that here and grab your copy.

Happy writing!

Published on March 05, 2018 04:00

March 2, 2018

Genre Conventions and Reader Expectations

Shannon Dittemore is the author of the Angel Eyes novels. She has an overactive imagination and a passion for truth. Her lifelong journey to combine the two is responsible for a stint at Portland Bible College, performances with local theater companies, and an affinity for mentoring teen writers. Since 2013, Shannon has taught mentoring tracks at a local school where she provides junior high and high school students with an introduction to writing and the publishing industry. For more about Shan, check out her website, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Pinterest.

Shannon Dittemore is the author of the Angel Eyes novels. She has an overactive imagination and a passion for truth. Her lifelong journey to combine the two is responsible for a stint at Portland Bible College, performances with local theater companies, and an affinity for mentoring teen writers. Since 2013, Shannon has taught mentoring tracks at a local school where she provides junior high and high school students with an introduction to writing and the publishing industry. For more about Shan, check out her website, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Pinterest. We are just trucking through our Grow an Author series--a series where we hope to show you that when you write a novel, you're not just writing a book, you're growing into a author.

If you've missed a few Fridays, here are my February links to catch you up.

Discovering My Cast of CharactersDiscovering My SettingTime Out: Letting First Thoughts Settle Into PlaceDiscovering People Groups and Backstory

Now that we've spent oodles of time focusing on what I look for when I'm discovery writing my early scenes, I want to talk to you about genre conventions and reader expectations.

You may have thought about this before setting out to pen your novel, but discovery writers (read: pantsers), like myself, are notorious for neglecting to consider this aspect of noveling early in the process. I hear questions like this one here a lot (in fact, I've asked it myself):

"So . . . uh . . . my book has angels and demons and people, but, like, the people don't fall in love with the angels or the demons . . . so . . . but also there is romance . . . what genre would YOU say that is?"

Ever had this moment? It's like we're begging someone to define our story for us, a responsibility we should routinely shoulder as part of our writing process. I should clarify: you only need to worry about genre conventions if you're hoping to have your book published. If you're just writing for you, write, be free. Do it however you want. But if you're hoping your book will end up on a store shelf somewhere, you need to consider where it would be shelved and what readers who buy that type of book will be expecting.

There is nothing, NOTHING, quite so miserable as selecting a book from a shelf marked 'Mystery', taking it home, and finding out there isn't a mystery to solve at all.

As a reader, I expect books in the 'Mystery' section to contain certain things. I'm hoping for a mystery and some sort of detective. A guilty party and plenty of red herrings to distract both me and the detective from discovering who it is too quickly. There should be plenty of twists and turns and, at the end, I expect the mystery to be solved.

Every genre (category) has its own expectations. Here's a list of the main genres (yes, I'll miss a few) you'll find shelves for in major booksellers. I've noted several of the conventions that are typical of each group:

Romance-A love story is central-Plot focuses on the two people falling in love-Traditional romance: boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy gets girl back -Happy endings are expected

The 'Romance' genre is the most popular genre and has more subgenres than we can reasonably name. Some of them include historical romance, contemporary romance, romantic suspense, fantasy romance, paranormal romance. Truly, the list could go on and on.

The traditional genre is so popular and the reading audience so defined that some publishers have very strict guidelines for submissions. So strict it could be called formulaic. But these publishers have learned precisely what their readers want and if you're wanting to publish with them, be sure to look up their guidelines and tips. Such requirements can be as specific as "Main characters must meet before the second page." If you're good at following a tried and true formula, consider writing formula romance.

Fantasy-Features unique, fictional story worlds or alternate versions of worlds we know-Often set in an era long past where legend and myth play a role-Features magic systems or mystical power sources-Magical creatures are commonplace

Subgenres include urban fantasy, epic fantasy, high fantasy, among others.

Science Fiction-An outrageous but plausible setting (maybe future earth, alternate version of earth, outer space, deep ocean) -Science and technology play a key role (not necessarily science and tech as it currently exists, but a conceivably possible version of it)-Often explores the consequences of scientific endeavors, inventions, and innovative ideas

Subgenres of science fiction include space opera, first contact, apocalyptic/post-apocalyptic, cyberpunk. And there are many, many more.

Inspirational-Faith-based fiction, often Christian

This is such a broad generalization for a category, you can imagine the possibilities for subgenres are wide-spreading: inspirational romance, inspirational thriller, inspirational fantasy, and so it goes.

Horror-Intentionally instills fear, fascination, and/or revulsion in readers -A battle of good versus evil-Supernatural or psychological forces are often at work-Draws on the fears of the reader

Mystery (Crime/Suspense/Thriller)-A mystery to solve (maybe a crime)-A detective (professional or amateur) or team of detectives-A responsible party (often a guilty party)-Suspense-Red herrings (multiple suspects or distractions to keep you and the detective from solving the case too early)

I chose to categorize 'Mystery', 'Crime', 'Suspense' and 'Thriller' novels together. I did that because Barnes and Noble shelves them in the same section. When you walk into their stores, you won't find a 'Thriller' shelf, but you will find several 'Mystery' shelves housing all four of these genres. HOWEVER, they are specialized, they each have subgenres, and there are distinct differences. If you suspect you might be writing any one of these four genres, you'll want to read up on what makes them each unique.

Children's and Young Adult -Marked by the target age of the reader-Distinctions within this broad category: Picture Books (targeting up to age 5), Early Reader (targeting ages 5-7), Chapter Books (targeting ages 7-12), Young Adult (teenagers)

Within the category of 'Children's Literature' you can find nearly every genre of fiction. Most bookstores shelve these books by reader age, but publishers who specialize in this space often excel in specific genres. It's always good to research those who sell what you write.

Literary FictionSome fiction works do not easily fit into a genre and we often classify those books as 'Literary Fiction'. While category fiction can absolutely provoke deep thought and cause us to examine the world around us in profound ways, 'Literary Fiction' is often defined by this feature and does not easily provide an escape from our world. Instead it thrusts our thought life deeper into it.

I've given you a handful of the genres category fiction is divided into. There are others and not every bookstore or publisher defines them in precisely the same way, but it's important to know what your potential readers expect of you. Part of being an author is taking the necessary steps to learn, understand, and be able to intelligently explain why your novel would be a good fit for a particular publisher or reader.

And at this point in the writing process, it's important to understand the expectations. It brings clarity and direction to my writing sessions. I know it will do the same for yours.

Tell me, as you look at the list I've left you, can you find your project in there somewhere? Is it perhaps a subgenre or a mash-up of more than one of these main groupings? If you were to open your own bookstore, is there a category you would add?

Published on March 02, 2018 06:34

February 28, 2018

How to Plot Your Story and Create a Loose Outline

Jill Williamson is a chocolate loving, daydreaming, creator of kingdoms. She writes weird books in lots of weird genres like fantasy (Blood of Kings and Kinsman Chronicles), science fiction (Replication), and dystopian (The Safe Lands trilogy). She has a podcast/vlog at www.StoryworldFirst.com. You can also find Jill on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, or on her author website. Tagboth (Tag for short) is a goldhorn dragon from Belfaylinn, a hidden fantasy realm on the western end of the Sargasso Sea. Jill is working on the first book of this tale for this year's Grow an Author series.

Jill Williamson is a chocolate loving, daydreaming, creator of kingdoms. She writes weird books in lots of weird genres like fantasy (Blood of Kings and Kinsman Chronicles), science fiction (Replication), and dystopian (The Safe Lands trilogy). She has a podcast/vlog at www.StoryworldFirst.com. You can also find Jill on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, or on her author website. Tagboth (Tag for short) is a goldhorn dragon from Belfaylinn, a hidden fantasy realm on the western end of the Sargasso Sea. Jill is working on the first book of this tale for this year's Grow an Author series.At this point, now that I feel confident about my characters, storyworld, and the backstories of each, I'm ready to plot out my story. I've shared before that I'm a hybrid author. In all honesty, I write my books mostly by the seat of my pants, but I'm also a planner, so I like to make lots of plans as to how that seat-of-the-pantsing will go. I make a list of scenes. Then I'll write those scenes. Unexpected things will happen as I'm seat-of-the-pantsing, and I'll have to tweak my list of scenes. Then I'll go through my manuscript, write out each scene on a 3 x 5 card, then storyboard it to fix the problem places.

But I'm getting ahead of myself.

Right now I need to create a loose plot outline. I need to have a plan for the end of this book. A plan that's going to work. Over the years, I've done this in many ways. Here is the process I'm using for Onyx Eyes.

I had wanted Onyx Eyes and it's sequels to be 20-page books. But as I studied the chapters I'd already written, I noticed that my second turning point—also known as the "Break into act two" part of the story or the "Set off on a Noble Quest"—had happened at the end of chapter six. So if I was going to follow a mathematically perfect three-at structure, I would need to have 24 chapters in this book.

Hmm . . .

Honestly, that's realistic for me. I write long. Better to give myself room in case I need it. ;-)

So I opened Microsoft Excel and created this little worksheet. It's really no different from my other plotting charts I've used before, but this time I put in 24 chapters, a prologue, and an epilogue. (Don't know if I'm going to want an epilogue or not...)

I also added some of the three-act structure elements to help me as I plot. Here's what mine looks like. If you've like to print out your own copy, click here.

Then I fill it in.

This process takes me quite a while. Usually I can do it in a day, but it sometimes takes longer. If I get stuck, I tend to think through the problem spots while driving or doing chores, or (the magical "good idea" place for all writers) while in the shower. ;-)

Honestly, I might not be able to fill in an idea for every chapter at this point, especially those chapters in parts three and four. But I'll try. If things change later, that's okay. The point is to give myself a map to follow.

If you're trying to sell your book to a traditional publisher, you'll need to write a synopsis and perhaps create a book proposal. If that's my plan, this outline would help me with all that. I'm going to talk about writing a synopsis and creating a book proposal in a couple weeks.

Using the chapters I've written so far, below you will see what I wrote on my form. I like writing in pencil in case I need to erase. And I can always copy my Excel file into a new spreadsheet and type in my plot information as well. It's actually easier to edit that way, but I'm often old school about using pencils and papers and such. Do what works best for you.

Warning: there WILL be spoilers here. :-)

Prologue - (KAITLYN POINT OF VIEW) - Sixteen-year-old Kaitlyn's best friend recently disappeared. Now her brother, Quinn, is acting CRAZY. She wants to figure out what is going on.

PART ONE: Glasderry

1 - Setup (Hero in his ordinary world, not yet living his dream) - (DRAKE POV) - Drake, a Grounder knight, has been engaged to Princess AyannaRynn for years, but when a royal contingent from the enemy Aerial kingdom comes to court, the Grounder king annouces that his daughter will marry the pompous Aerial prince SuelAlefric. Drake is furious. Later he visits Ayanna, but neither of them know what to do.

2 - Turning Point #1: Opportunity - (DRAKE POV) - That night, Princess Ayanna goes missing. Drake is accused, and the Grounder king gives him five days to find her or take the blame. Drake confronts the king about his promise to allow Drake and Ayanna to marry. The king says that peace is more important than promises made years ago. Drake starts his investigation. Clues lead to the Aerials, but Drake cannot go undercover in Aerial territory without wings, and he is not a strong enough stonecaster to know such magic.

3 - Stage II: New Situation - (DRAKE POV) - Drake goes to visit Tulak, the Old One who took him in after his mother abandoned him as a child. Drake asks what spell might give him wings. Tulak says that only using onyx to bond with a winged creature could accomplish such a thing, but that is the darkest of magic and forbidden. Drake considers Tulak's warning, but his mind is made up. He would do anything to find the princess.

4 - (DRAKE POV) - Drake climbs a mountain and enters the cave of a dragon named Tagboth. He performs a spell that enables him to bond with the dragon. The spell is quite painful and requires the use of his True Name.

5 - (DRAKE POV) - Drake learns to fly with his new wings. He takes the mask of Prince Suel's Aerial servant. Whenever Tagboth speaks to Drake, he uses his True Name. Drake tells him to stop. It can be dangerous if anyone should overhear it. The dragon is unsympathetic. Drake stole his wings, after all.

6 - Turning Point #2: Change of Plans - (DRAKE POV) - Travels with Prince Suel back to the Aerial kingdom. He leans that the Aerials put her in a human home as a changeling and brought the human here as a slave.

PART TWO: Idaho

7 - Stage III: Progress - (DRAKE POV) - Drake finds a male changeling in a human home, masked as a teenage boy named Quinn. Drake arrests the fairy, creates a mask of Quinn, then takes the teenage boy's place. He learns that the neighbor girl went missing a few weeks ago. He asks questions of any human he can find, trying to discover information about the missing girl, who he believes is Princess Ayanna. Quinn's sister Kaitlyn doesn't seem to like her brother at all.

8 - (DRAKE POV) - Drake goes to school as Quinn and continues his investigation of the missing girl, questioning anyone he can. Kaitlyn confronts him, angry that he is "harassing her friends." Drake begins to experience pain from the magical bond he shares with the dragon.

9 - (KAITLYN POV) - Kaitlyn sets up some old video baby monitors, putting one in her room and the other in Quinn's. If he's doing drugs, she's going to catch him in the act. That night she hears him talking to the lizard. Then the lizard talks back! The lizard can talk? It calls Quinn a different name. Quinn takes off his shirt, and Kaitlyn sees him stretch out . . . his wings.

10 - (DRAKE POV) - Drake learns to use a computer and seeks information about the missing girl. He follows a lead across town, but just as he finds a clue, he is attacked by Aerials and wounded.

11 - (KAITLYN POV) - Kaitlyn researches fairies—because that's what has taken her brother, right? When he finally comes home, she goes into his room to confront him. But he is bleeding badly. She helps him. Then she tells him she knows he has wings and that he's a fairy. She also knows his fairy name, and that means he has to do what she wants. And she wants him to help her find her brother.

12 - Turning Point #3: Point of No Return - (DRAKE POV) - The human girl knows his name! This is all Tagboth's fault. Drake has no choice to obey her. He tells her about Princess Ayanna and the fairy changelings and pleads his case. His mission is important. In the end, she wins. Back to Belfaylinn they go to find the real Quinn.

That's all I have so far. I'll keep working on it. :-)

Do you plot out your stories? If so, is it similar to this or different? Share in the comments.

Published on February 28, 2018 04:00

February 26, 2018

Five Guidelines For A Great Chapter Two

Stephanie Morrill is the creator of GoTeenWriters.com and the author of several young adult novels, including the historical mystery, The Lost Girl of Astor Street (Blink/HarperCollins). Despite loving cloche hats and drop-waist dresses, Stephanie would have been a terrible flapper because she can’t do the Charleston and looks awful with bobbed hair. She and her near-constant ponytail live in Kansas City with her husband and three kids. You can connect with her on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, Instagram, and sign up for free books on her author website.

Writers and writing teachers tend to focus a lot of attention on chapter one. I include myself in this list. I think this is partly because it's a very important chapter, but also because it's a bit easier to teach. Not easy to do well, of course, but there are a lot of story elements that need to be hit right away to draw a reader in, regardless of the genre or length of the work.

Once we get beyond the opening, the "how to" of crafting a good story can get a bit murkier.

Last week I talked about writing the first chapter in the context of how I can't do a good job of planning my story until I have written the first few chapters. The reason I need to write several chapters and not just the first is because that gives me time to explore several aspects of my characters' lives.

So, let's talk about what comes after that all-important chapter one. What elements are required to craft a great chapter two? Here are five guidelines:

Guideline #1: Show us different people.

If you're writing a book with just one point of view character, you will want to use chapter two to introduce more of your characters. In The Lost Girl of Astor Street, chapter one introduces us to Piper's two closest friends, a boy she likes, her brother, and her housekeeper. Chapter two introduces another family in the neighborhood, her father, and some other characters.

If your book has multiple point of view characters, chapter two sets up a good opportunity to switch perspectives. There's no rule that you must, and sometimes it depends on the length of the work. For example, in an epic fantasy you might stay with your first point of view character for several chapters before switching, while in a shorter romance novel, you'll almost always switch perspectives at chapter two.

When you do switch to one of the other characters, whether it's chapter two or later, many of the same guidelines for chapter one apply. The introduction of this character will be most effective if you show them doing something that matters, something that's interesting, and so forth. You want to show what they want, what they need, and what's keeping them from it. And you want to show what their normal—or their normalish—life looks like.

Most of the time you want all major characters introduced, or at least implied, in the first quarter of your book. By implied, I'm referring to characters who are mentioned or understood to exist without us ever seeing them, which is necessary in some situations. Like Aslan in The Lion, The Witch, and The Wardrobe, or Voldemort in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone. We don't need to see them on the page, and that would make no sense for the story, but we do need to know they exist.

For my book, Within These Lines , I was unable to set up all major players as early as I normally would because Taichi's family had not yet been sent to the concentration camp. So it's okay to not do it, just make sure you have a reason why.

Guideline #2: Show us a different emotional side of your main character.If chapter two is written in the same POV as chapter one, then you'll want to choose something that shows a different emotional side of this character. For The Lost Girl of Astor Street, in chapter one I showed Piper as sassy, clever, and in-control. In chapter two, when Piper comes across her best friend having a seizure, Piper is terrified, lost, and has no idea what to do.

When you show the reader different facets of your character, not only does it make your character feel more real, but it also helps to engage the reader more fully.

Guideline #3: Show us another place.

Unless this doesn't work with your story, you likely want to show the reader a new place in chapter two. If you're switching POV characters, the change of setting comes naturally, but it works well for stories told from just one perspective too.

Guideline #4: Show us a deepening.

In chapter one, you should have shown us what the character wants, what they need, and what's keeping them from that. Chapter two is a place to deepen these.

Maybe in chapter one, we caught a glimpse of your character wanting to get away from his hometown. In chapter two, show us yet another motivation for leaving.

And in addition to that, chapter two is a good time to strengthen either the lie the character believes or whatever is holding them where they are. Building a strong lie is key to building a strong conclusion.

Guideline #5: Give us a greater understanding.

In the same vein as deepening those wants and needs, this is also a great opportunity to answer some questions you raised in chapter one. Going back to chapter one of The Lost Girl of Astor Street, the reader knows that Piper's best friend has some kind of health issue, but they don't know what it is until chapter two when Piper finds her having a seizure. The reader now has a greater understanding of the situation.

For Within These Lines, in chapter one Evalina goes to the farmer's market like she does every Saturday morning to see Taichi, only his family isn't there. She's so scared that for the first time ever, she calls his house.

For chapter two, I wanted the readers to get a greater understanding of what an uncertain time this was, particularly for Japanese Americans and those who cared about them. I also wanted the readers to see Evalina and Taichi together so they would see their connection, so that's where I focused the attention.

How is your chapter two looking? Are there other guidelines you would add to this list?

Published on February 26, 2018 04:00

February 23, 2018

Discovering People Groups and Backstory

Shannon Dittemore is the author of the Angel Eyes novels. She has an overactive imagination and a passion for truth. Her lifelong journey to combine the two is responsible for a stint at Portland Bible College, performances with local theater companies, and an affinity for mentoring teen writers. Since 2013, Shannon has taught mentoring tracks at a local school where she provides junior high and high school students with an introduction to writing and the publishing industry. For more about Shan, check out her website, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Pinterest.

Shannon Dittemore is the author of the Angel Eyes novels. She has an overactive imagination and a passion for truth. Her lifelong journey to combine the two is responsible for a stint at Portland Bible College, performances with local theater companies, and an affinity for mentoring teen writers. Since 2013, Shannon has taught mentoring tracks at a local school where she provides junior high and high school students with an introduction to writing and the publishing industry. For more about Shan, check out her website, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Pinterest. Sometimes the things you write aren't supposed to end up in your finished work. Sometimes the things you write are just for you.

I finished writing a fantasy book not long ago that features four distinct people groups. During my early writing sessions, these people groups crept up organically--my hero meeting each group as she journeyed from one side of her island to the other. As each people group climbed onto the page, as they began to take on life and color, I had to step away from my main work and discover what makes each of them unique. I needed to understand their collective wants and their histories. I needed to know whose side they'd be on in any number of battles and I needed to find out where I'd find nuances within the group. On the whole, I needed to discover how these people fit into the story I was telling.

I tackled this task in much the same way I tackle everything else. After a period of stewing on my first thoughts about the people group in question, I sat down in the chair and I prepared to write.

This kind of writing is a little different for me because I have no intention of including it in my novel. Because of that, I open an entirely new document for these writing sessions. Once I discover who these people are and what makes them tick, I have to decide what specifically the reader needs to know and when he needs to know it. Not everything I write during these sessions will be shared in the novel, and I'll carefully unveil the necessary elements as the story requires them.

Another thing I do differently when I'm discovery writing great swathes of history: I don't always set a timer and sprint my way through. I'm loathe to abandon the practice entirely--it works for me--but I do allow myself to stop and research various things as I move forward.

Here are five things I'm looking to understand as I set out on this portion of storytelling:

Origin Where did this people group come from? Are they native to this land or did they arrive here later? If so, how much later? Were they a colonizing force? Maybe they were refugees, escaping persecution elsewhere? Do they know their history? Does their past matter to them at all? Does their background put them at odds with any of the other people groups in my story? Does their history give them natural allies? Does their origin affect the story problem? Does it affect my hero or anyone else in my cast of characters?

BeliefsWhat does this people group believe about life and death? What do they believe about their own creation? Are they religious? What do they value above all else? Does everyone in the people group believe the same thing? What do their differences stem from? Do they have a place of worship? How does my hero and the cast surrounding her feel about the beliefs of this group? Does it make them sympathetic to the group or critical?

HabitationHow does this people group live? Do they share households with family members? Are they solitary dwellers? Does the entirety of the people group live in one general location or are they spread across your world? Why have they chosen to live this way? How does this people group sustain themselves? Are they skilled in a variety of trades? How has their origin and belief system factored into where and how they live and survive?

LeadershipDoes your people group have a clear leader? Is there a government in place? If so, what kind? Is it a kingdom or a form of democracy with representatives and votes? Is there a ruling class? Are the rulers benevolent or uncaring? Under this leadership, are the people united? Are they looking for an opportunity to fight themselves free? Are they in full rebellion? What are the stated priorities of the leadership? What are the perceived priorities of the leadership? What are the actual priorities of the leadership?

ThemeIf I'm writing with a theme in mind, I want my discovery writing sessions to unearth just how this people group can serve my theme. When I was writing my second book, Broken Wings, a theme had developed independent of my intentions: worship as warfare. I loved this concept and wanted to serve it by inserting characters that helped me along. I did this by creating a rank of angels called the Sabres. Describing them, I said this,

. . . it's his wings that so separate them from any other angel I've seen. Their beauty is staggering, their design inexplicable. Where I expect to see rows and rows of snowy white feathers, one blade lies on top of another--thousands of them--sharp and glistening silver . . . they rub one against the other, trembling, sending music far and wide.

The wings of the Sabres are dangerous and useful in battle, but it's their song that does the real damage in warfare. Whenever I create a people group, I remember how effective my Sabres were in serving my theme and I ask myself, "How can this people group do the same for this story?"

The wings of the Sabres are dangerous and useful in battle, but it's their song that does the real damage in warfare. Whenever I create a people group, I remember how effective my Sabres were in serving my theme and I ask myself, "How can this people group do the same for this story?"I've given you just five things to look for as you settle in and discover the kind of backstory that will inform you as an author and make your tale all the richer. Though, in truth, much of it may never make it onto the page.

It's easy to get bogged down in this portion of noveling, easy to lose time writing pages and pages of unnecessary words. Discovery writers must be careful not to tumble down the rabbit hole of excessive world development. It's a delicate balance and one you get better at as you grow. Give your pen the freedom to roll across the page but keep in mind that the most important thing you're looking to discover is how each people group touches your hero, her journey, and the problem she's trying to solve.

When you're creating people groups, what is it you're looking to discover? What elements of their backstory do you need to understand to make these characters come alive on the page?

Published on February 23, 2018 04:00

February 21, 2018

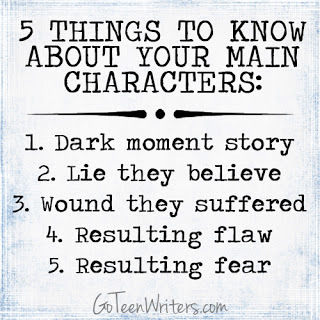

Deeper Character Development: 5 Things to Know About Your Main Characters

Jill Williamson is a chocolate loving, daydreaming, creator of kingdoms. She writes weird books in lots of weird genres like fantasy (Blood of Kings and Kinsman Chronicles), science fiction (Replication), and dystopian (The Safe Lands trilogy). She has a podcast/vlog at www.StoryworldFirst.com. You can also find Jill on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, or on her author website. Tagboth (Tag for short) is a goldhorn dragon from Belfaylinn, a hidden fantasy realm on the western end of the Sargasso Sea. Jill is working on the first book of this tale for this year's Grow an Author series.

Jill Williamson is a chocolate loving, daydreaming, creator of kingdoms. She writes weird books in lots of weird genres like fantasy (Blood of Kings and Kinsman Chronicles), science fiction (Replication), and dystopian (The Safe Lands trilogy). She has a podcast/vlog at www.StoryworldFirst.com. You can also find Jill on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, or on her author website. Tagboth (Tag for short) is a goldhorn dragon from Belfaylinn, a hidden fantasy realm on the western end of the Sargasso Sea. Jill is working on the first book of this tale for this year's Grow an Author series.Over the past few weeks, I've done a lot of problem solving and worldbuilding. I now feel much more knowledgeable about my storyworld. I now know why the three people groups have been at war since they came to this land. And I have a reason why the Aerials justify human slavery.

There is one more area I'd like to spend time on before I really start plotting out my story in detail. I'd like to do some deeper character development--at least on my two point of view characters: Drake and Kaitlyn.

I can start writing now. And in other books, I have started writing. If I want to get something down and out of my head, or I want to see if the idea has merit, I might write some chapters. Having a goal, motivation, and story conflict is enough to get things rolling, BUT . . . I can't get very far knowing only those things. I need to know who my character is if I'm going to write a believable character arc. I can't show my character growing if I don't know what's broken in him.

I've written twenty books, and I never used the same process more than once in how I came up with my plot or developed my characters. I'm always learning, so when I read a new craft book, I take bits and pieces from it and try to incorporate that into my ever-changing process.

With character development, you've all likely seen my gigantic character chart. And while I love that chart, it's very rare that I ever completely fill it in for anyone but my few main characters. And even then, sometimes I don't. Most of the things on my giant character chart don't matter to the heart of the story. A story is about a character who rises up to face a situation and comes out changed on the other side. What he drives, whether or not he has a cat, and his favorite breakfast cereal don't matter. It might be fun to know those things, but they don't drive the story.

I do, however, have a handful of things I must know about a character in order to "play them" in the book. I think of this in terms of method acting. I need to get to know these characters deeply, so that I can accurately portray them in the story. And since I can't literally sit down and interview them, I do so in my head.

The first thing I need to ask them is, "Who are you?" And I'm not looking for a long, drawn out answer. I'm looking for a very specific label. It's the same label I would use to describe my character in a logline pitch statement. I want my character to give me an adjective + a noun that describes who they believe they are. This will help me get to know my character and to grow them over the course of the story.

When talking about loglines, over and over I've used the two examples from JAWS and Miss Congeniality, respectively: landlubber sheriff and ugly-duckling (female) FBI agent. Both of these character descriptions are a great place to start because they show conflict in what I know the character is going to face in the story. In JAWS, the sheriff is going to have to go out in a boat to try and kill a giant shark. That's hard to do for anyone, but especially a man who is afraid of the ocean. And in Miss Congeniality, the fact that she is an ugly-duckling FBI agent isn't such a big deal, until she has to enter a beauty pageant. Now we have trouble.

I've been working on this for Onyx Eyes, and I have it all figured out for both Drake and Kaitlyn. I'm going to give it to you one step at a time. To start, here are the descriptions I've given them, then as you read the five things to know about your main character below, you'll see why I chose those descriptions. You don't have to come up with any of this in order. It actually helps me to start with the dark moment story, so I often don't have my character adjective and + noun until later.

Drake: I am an abandoned warrior

Kaitlyn: I'm an invisible daughter.

1. The dark moment story.

What is that character's dark moment story? This is something that happened to them long before the story starts, often in childhood. This event was so powerful, it branded a lie into the character's heart, and ever since that day, he has been a walking definition of that lie. Defined by it. You need to dig until you figure out what that story is. Not just "he was abused by his dad." You need a moment in time that could be watched on a film, complete with five senses details. Here are mine:

DrakeDrake: My father died when I was seven. He was a soldier and was fighting against the Aerials, who were trying to take control of some Grounder border villages. He and I were close. He taught me so many important things. I loved sparring with him with the wooden swords he made me. I still hear his voice sometimes, telling me not to drop my guard.

DrakeDrake: My father died when I was seven. He was a soldier and was fighting against the Aerials, who were trying to take control of some Grounder border villages. He and I were close. He taught me so many important things. I loved sparring with him with the wooden swords he made me. I still hear his voice sometimes, telling me not to drop my guard.Anyway, he died in battle. A soldier came to the door and told my mother. I was sitting on the floor just inside the door, whittling a dragon from a piece of cedar. I saw the blood splattered on the soldier's clothes--I could smell it--and I wondered if that was my father's blood. To this day, the smell of blood makes me think of my father, of his bravery.

When the soldier left, my mother got angry. She started packing clothes and muttering about how she knew this would happen, how my dad had been a fool to fight an unwinnable battle. My mother finished packing the bag and carried it to the door. She looked down at me and said, "I'm leaving. You'll stay here. I have a man up in Novahorn who'll take me in, but he doesn't care for children." And then she left. The door closed behind her with a loud thump. I stared at it for a long while, then I finally got up and opened it. I saw her in the distance, walking away, bag in one hand. She didn't look back.

KaitlynKaitlyn- (Kaitlyn was tricky because she has two families. So I decided to use the family she was born into [spoilers!] because that would have been the family she lived in during her formative years.)

KaitlynKaitlyn- (Kaitlyn was tricky because she has two families. So I decided to use the family she was born into [spoilers!] because that would have been the family she lived in during her formative years.)I came from a really large family with seven children. I was child number five in the long line. My older brothers were already married and had children of their own, and it was my job to cook all the meals and to look after my little sisters and my nieces and nephews. I love my family, but I often felt more like a mom than a child. And it was really hard to get any attention from my parents. Father worked as a soldier, and mother was a maid in the castle. I did one thing for myself back then. I loved to bake. So when the marketplace had a baking contest, I entered my best cuskynoles, which are bite-sized tarts filled with apples, pears, figs, and raisins. My brother always said I made the best cuskynoles--even better than his wife's, so I wasn't terribly surprised when they made the top five. My entire family was summoned to the marketplace the next day, where judges would taste the top entries in each category and choose winners.

I told my family about it, and my parents both promised to be there. The next day, I arranged for our neighbor to come over and watch the children so I could go to the market. I won first place. But my parents never arrived. No one from my family came. That night at home, I made roasted chicken with potatoes and carrots with my award-winning cuskynoles for dessert. Everyone ate with no mention of how the judging had gone. I was working up the courage to share when my elder sister announced she was getting married. The whole house erupted in celebration, and I never got a chance to tell anyone I had won or show them my ribbon. I cleared the table and did the dishes, feeling completely forgotten. I never made cuskynoles again. And I hate roasted chicken.

2. What lie does your character believe about himself as a result of that dark moment story?

Drake: I am worthless. No one wants me around.

Kaitlyn: I'm invisible. Nobody sees me. Everyone else is more important that I am. There must be something wrong with me.

3. What wound did your character suffer from that event?

Drake: His wound was being abandoned and the shame of being unwanted by his own mother.

Kaitlyn: Her wound is being forgotten and the immense disappointment that came with it.

4. What flaw came out of this? How does your character behave in order to protect himself from suffering another similar wound and being hurt again?

Drake: He is distant from people. A loner. Sometimes considered cold. Very independent. He finds it difficult to develop close relationships with people and has never had a close friendship.

Kaitlyn: She doesn't rely on others. People can't be trusted. She is an over-achiever, a hard worker, and overly self-critical. She has a hard time making decisions, and is unable to be spontaneous because she doesn't want to risk future disappointments.

5. What is your character's greatest fear?

Hint: It should be related to his dark moment story manifesting again his his life. And it should manifest again, in the black moment or disaster part of your three-act-structure.

Drake: His greatest fear is that he is unlovable. That he might love someone and be rejected.

Kaitlyn: Her greatest fear is that she is worthless and doesn't matter in this world. That she could vanish and no one would ever miss her.

Okay, so fast-forward to the present...

What is their greatest dream?Knowing all those things about your character's past will help you discover what your character wants and why? This is not a plot question, but an internal one. This is something deep inside your character that propels him through the story.

Drake wants to be part of a family.

Kaitlyn wants a deep and meaningful friendship with someone who sees her.

And since this series will have a romantic subplot, it's important that Drake and Kaitlyn will help each other overcome their lies and wounds and achieve their greatest dreams. They are a good fit because if Drake takes the risk to love someone and is loved in return, he will be fiercely loyal because such a relationship will be priceless to him. That's the kind of devotion Kaitlyn needs to achieve her greatest dream.

And Drake's greatest dream is that he would be part of a family, and while Kaitlyn was hurt by her family, she still loves them. And they are a big, wild, crazy family that will accept Drake as one of them, even if they don't give him a lot of attention. That's the kind of family Drake has always wanted.

One more thing to mention. Once you have all this figured out, you need to give your character some competing goals. I'm currently working on my sixth and (final!) Mission League book. And Spencer is going to reach a place where his two more important goals conflict (stopping the bad guys OR signing a contract to play college basketball at a D1 school), and he'll be forced to choose between them. What he chooses could very well change his life, but since it's at the end of the story, he will now be equipped to make that choice (the right choice), when at the start of book one, he was far too immature to even think about such a selfless act.

So here are some competing goals for Drake and Kaitlyn. If I plot (and write) my story well, hopefully they will both be forced to choose between these goals in the story. They might choose wrong at first, but by the end of the story, they should have grown enough to sacrifice something important to do the right thing. These goals might not mean much to you, but they are events in the story that I will work hard to make sure my characters will have to choose between at some point.

Drake: Find the missing princess. Stop the Aerial slave trade. Help Kaitlyn find her missing brother.

Kaitlyn: Find her missing brother. Find out who she is. Rescue Drake from prison.

Can you answer the following about your characters?

Who are you? (Give a specific adjective + noun.)

1. What is your dark moment story?

2. What lie do you believe because of that event?

3. What wound did you suffer as a result of that event?

4. What flaw did you develop from that wound?

5. What is your greatest fear?

Because of all that, what do you want most in life?

What else do you want (that will compete with what you want most in life)?

Share your answers in the comments!

Published on February 21, 2018 04:00

February 19, 2018

8 Keys To Opening Your Story The Right Way

Stephanie Morrill is the creator of GoTeenWriters.com and the author of several young adult novels, including the historical mystery, The Lost Girl of Astor Street (Blink/HarperCollins). Despite loving cloche hats and drop-waist dresses, Stephanie would have been a terrible flapper because she can’t do the Charleston and looks awful with bobbed hair. She and her near-constant ponytail live in Kansas City with her husband and three kids. You can connect with her on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, Instagram, and sign up for free books on her author website.

So far in my thread of the Grow An Author series, I've talked a lot about getting ready to write. Here is a list of my posts so far, in case you need to catch up:

From Story Spark to Story Blurb

How To Effectively and Efficiently Do Research

Ideas for How To Organize Your Research Notes

The Three Things You Need To Answer About Your Main Character

Even with all this work, I'm still not ready to dive full-on into my first draft. There's more planning to be done. But I've learned the hard way that I'm not a very good planner unless I have written a few chapters. I don't really understand why that is, but it's pretty common among novelists.

How do you know where to start your story? Writers ask this a lot, and I have a not-so-helpful answer that I will follow up with a more details answer.

The not helpful answer: For me, it's a gut thing.

We all have parts of writing that come more naturally to us than others, and for me, my instincts with where to begin my story nearly always serve me well. I know lots of other writers who have to "write their way" to their beginning, who almost always scrap the first few chapters they write, so if that's you, don't despair.

But that it's "a gut thing" isn't terribly helpful, is it? So here are eight elements that I feel are key to creating a compelling story opening.

Start with your main character

It's almost always a good idea to begin with your main character. This is likely why the reader has picked up your book. To read about this character and their story, so it usually works best to begin with them.

You can probably name books that you know and love that don't do this. Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone is the first one that pops to mind for me. So while I think it can work to ignore this bit of advice, I think most stories are served best by beginning with the main character.

Start with your main character doing something interesting and pertinent

You have maybe heard the writing advice to start "in media res" or in the middle of action. I do agree with this, though I do wish whoever first said it would have added to start with action, "that matters."

For example in The Hunger Games, we begin with Katniss sneaking out to go hunting, which is both interesting and something that's important later in the story.

Skip the "here's what you've missed" info-dumpy opening

Just don't do it.

There aren't many things that I'll come right out and say, "Never do this," but this is one. Yes, I know you see bestselling authors do this. I don't know why their editors are okay with it, I really don't. I'm actually reading a book right now from an author who I love, but the first TWO CHAPTERS are all backstory. I kept thinking things like, "If this wasn't this particular author, I would have already closed this book." And, "When does the story actually start?"

I know it's easy to believe that if the reader doesn't know all these things that happened in the main character's past, or in your fantasy storyworld's history, they won't be able to adequately appreciate or understand what's going on. But your job in the first chapter is to show the reader why they should be intrigued by this character, not to tell them every single thing they need to know.

It's like when you meet someone for the first time, and you have a bit of a crush on them. You're intrigued by them. You want to know more. You don't need to know everything about them—often it's better if you don't—and you still feel that this is a person you want to spend more time with.

That is what you're trying to create for you reader, and I have yet to read an info dump opening that does this.

Start with action that says something about who the main character is, and why we should care about them.

Going back to The Hunger Games, the reason that opening scene works so well is that Katniss isn't just doing something interesting and intriguing. What she's doing also says something about who she is. She's a provider. She's responsible. She takes care of her own. These are traits of hers that make us care about her, and make us want to find out what happens next.

Start in the character's normal world.

It's helpful for readers to see what kind of life this character is used to, but we don't need very much, and it doesn't have to be a completely normal day either. In The Hunger Games, it's the Reaping day. We see just a glimpse of what Katniss's everyday existence is like, and that's enough.

In Cars we see Lightning McQueen tearing it up on the race track and nearly-winning with no help from anyone else. That's his normal world.

In Harry Potter and The Chamber of Secrets, Harry is having a terrible birthday at the Dursleys', like always.

Sometimes what's helpful for me is to consider how I can portray a normal day, but with a twist. For Katniss, it's an ordinary day, except she knows the reaping is coming. For Lightning McQueen, it's another race, only this time it's a tie. And for Harry Potter, he's used to terrible birthdays, but on this one, Dobby the house elf shows up.

Start with hints of what they want, what they need, and the barrier between

This, of course, doesn't mean stating, "Harry had been neglected all his life, and what he wanted more than anything was to belong somewhere." This means finding a clever way to show the audience what the character lacks. (And it's not always what the character thinks they lack.)

Lightning McQueen wants to win the Piston Cup so he can have the best racing sponsor. What he really needs is friends and people who love him just as he is. The barrier keeping Lightning from this is his own ego. We see all of this in the first few minutes of the movie.

Consider your tone

Another danger with blindly following the "start with action" advice is that writers sometimes will pick an interesting, action-filled, whizbang of an opening ... that doesn't match the tone of the rest of the novel. A cozy mystery doesn't open the same way as a historical romance. Chapter one of a middle grade adventure novel doesn't sound like epic fantasy.

If you're already following the above advice, having a mismatched opening isn't very likely to happen to you, but it's something to be on the lookout for if you're trying to amp up the action in the beginning.

Create questions

More than anywhere else in the novel, in your first pages you want to create questions in the reader's mind. Why did this character wake up scared? Why is she sneaking out? What is she afraid of? What's so important that she's risking getting into trouble? These are a few of the questions that I raised when I wrote the opening of Within These Lines, and they were all answered within a few paragraphs. You're not trying to frustrate your reader by never answering any questions. You're just trying to evoke their curiosity.

Here are the first few hundred words of Within These Lines. After, I'll give a brief summary of how I think this fits the above criteria. (Besides my editor, you guys are the first to read any of it!)

Chapter One: EvalinaSaturday, March 21st, 19423 months after the Japanese attacked Pearl HarborSan Francisco, California

When I jolt awake, the familiar fear smothers my early morning thoughts and thrums through my veins. I gasp for breath, as if there’s a shortage of oxygen, until I convince my rhythm to slow.

No light comes into my room—too early—but I draw back a panel of my gingham curtains and peek outside anyway. Just to reassure myself that it’s all still there—my narrow street, the houses of my neighbors, my entire world.

And there it is, the sound that roused me from my fearful slumber. The faint squeak of bicycle pedals as the paperboy pushes himself up our steep hill. When I look closely at the front door of the house across the street, I spot the newspaper lying across the front step like a welcome mat.

The planks of my wooden floor creak as I slip out my door, past Mama and Daddy’s quiet bedroom, down the narrow, steep staircase, and out the front door. Even in the dim lighting of the streetlamp, the bold headline of the San Francisco News reaches up and grabs at my heart:

FIRST JAPANESE READY TO LEAVE COAST

No, no, no my heart pounds as I reach for the newspaper.

How can you know something is coming, spend every waking moment with it gnawing at you, and still feel a jab of shock when you see it begin?

I devour the article that details how over sixty Japanese Americans living in Los Angeles have voluntarily gone to Manzanar—a place in southern California I had never heard of until earlier this month—to prepare to receive new residents.

“Evalina?”

I jump at Mama’s groggy voice. “Hi. I didn’t mean to wake you. I just couldn’t sleep.”

With her puffy eyes, Mama looks at the newspaper in my hand. Her mouth is set in a grim line. “This obsession is not healthy, Evalina. I know you’re worried, but we have nothing to fear. I don’t know what it will take for you to believe that.”

“Mama, they’re going to make all the Japanese go.” My voice cracks. “Even the ones who were born here. Like the Hamasakis’s children.”

“Who?”

I swallow. I shouldn’t have mentioned them by name. “One of our produce suppliers at Alessandro’s.”

“Oh. Yes, of course.” Mama stifles a yawn, seeming unaware of how far I tipped my cards. “You’re safe, honey. I know sometimes those articles make it sound like Italians are going to be rounded up too, but we’re not.”

“If the government was being fair, we’d be forced to go too. Especially a family like ours—”

“But we’re not. Stop looking for trouble, and come inside before somebody sees you looking indecent.”

I’m wearing my favorite pajamas, which have long pants and long sleeves, but Mama hates that I bought them in the men’s department. I shuffle back inside the house, and Mama soundlessly closes the door.

She scowls at me in the gray light of the entryway. “I’m going back to bed. I’m tired of these conversations, Evalina. I’m tired of waking up to you crying. Or hearing from your friends that you’re distracted and preoccupied by the news. This is not normal behavior for a girl your age.”

“Our country is at war.” I force my voice to be soft. “What am I supposed to act like?”

Mama’s mouth opens. I’m wearing away the thread of patience she woke up with—I can see it in her eyes—but I don’t know how to lie about this. Why, I’m not sure, because I’m certainly lying about plenty of other things.

“Evalina…” Mama takes several thoughtful breaths before saying. “I’m going back to bed. You do the same.”

Start with your main character: Done. Again, there are times when I've seen writers start with not-the-main character and it works fine, but I think those are exceptions.

Start with your main character doing something interesting and pertinent: Evalina is sneaking out of the house to get the morning paper, which is interesting behavior for a teenage girl, and directly relates to the main plot.

Skip the "here's what you've missed" info-dumpy opening: Done. Other than when I spell out when and where we are in the chapter header, which is customary for historical fiction, the reader hits the ground running with minimal information.

Start with action that says something about who they are, and why we should care about them: From this scene, we know that Evalina cares deeply about something that is happening around her, but not really to her. Anytime you can show a main character caring about something that's bigger than them, that's attractive to readers.

Start in their normal world: I considered starting before the bombing, which would really be Evalina's true normal world, but when I learned the timing of when the Japanese Americans were evacuated, I decided after would serve the story better.

Start with hints of what they want, what they need, and the barrier between: This is just the first 600 words so you don't get the full picture, but we see what's pressing on Evalina's heart, and you even get a hint of why this issue matters to her so much when she mentions the Hamasaki family by name to her mother. The barrier that's implied is that these are government decisions, and Evalina is a teenage girl with no power of her own.

Consider your tone: I wanted my opening to show the panic and uncertainty that saturated this time in history. That's why I have Evalina jolting awake from a dream about a bomb, and sneaking out of bed to find out what new, scary things have happened in the world.

Create questions: Some of the questions the scene evokes get answered very quickly. (Why is she sneaking downstairs? Oh, to read the newspaper.) Other questions are raised but not answered, like why is Evalina nervous that she "tipped her hand" by bringing up the Hamasakis? Or what else is she lying about?

Take a look at the openings of your stories. Do you feel like they're doing a good job of setting up the story you want to tell?

Published on February 19, 2018 04:00

February 16, 2018

Time Out: Letting First Thoughts Settle Into Place

Shannon Dittemore is the author of the Angel Eyes novels. She has an overactive imagination and a passion for truth. Her lifelong journey to combine the two is responsible for a stint at Portland Bible College, performances with local theater companies, and an affinity for mentoring teen writers. Since 2013, Shannon has taught mentoring tracks at a local school where she provides junior high and high school students with an introduction to writing and the publishing industry. For more about Shan, check out her website, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Pinterest.

Shannon Dittemore is the author of the Angel Eyes novels. She has an overactive imagination and a passion for truth. Her lifelong journey to combine the two is responsible for a stint at Portland Bible College, performances with local theater companies, and an affinity for mentoring teen writers. Since 2013, Shannon has taught mentoring tracks at a local school where she provides junior high and high school students with an introduction to writing and the publishing industry. For more about Shan, check out her website, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Pinterest. As a routine part of my writing process I give myself days at a time to do nothing but think. Well, not nothing. I'm usually scrubbing the bathroom, or preparing a Sunday school lesson, driving my kids around town, or putting together a conference talk. Sometimes I'm actually out in nature, hiking a mountain or splashing in the ocean. Those are the glorious days, but the truth is, so long as I make it a priority to come back to my manuscript sooner rather than later, these thinking days are incredibly valuable and, in truth, necessary.

If you've been following my writing process on Fridays, you'll know that at this point I've committed to a story idea and I've begun the process of discovery writing the opening scenes. I have the beginnings of a protagonist and the problem she's working to solve. A cast of characters is starting to take shape around her and my storyworld is blurry but is slowly coming into focus.

I've noticed that I've started to contradict myself here and there within the manuscript. Some days my hero has two brothers and some days she has three. Some days her father has a beard and some days he's clean shaven. During my first writing session, I set the story in the springtime, but I've since decided that autumn makes way more sense. I have the frame work of a religious system in place and I'm trying to decide if I want to include magic or not.

What I need to do now is stop and give the story time to become more than just an idea. I need to walk away from the business of writing and let the story settle into place in my gut.

Ever cooked a tri-tip? You pull it off the grill and it smells amazing, but if you cut into it right away, the juices inside the meat spill out and you're left with a dry hunk of cow. What's needed is not more time on the grill or even another dose of marinade. What the meat needs is time. If you leave the tri-tip alone for just ten minutes, the juices will redistribute and every slice will be full of juicy yumminess.

That's what I'm trying to do here. I've done a little cooking and now I need to let my story rest. To let it breathe. To let all the juicy ideas I have racing through my head redistribute. I need them to settle into place.

When a break like this is successful, I come back to the page excited because I have clarity. The influx of first thoughts that pummeled me during my early writing sessions have begun to settle into place.

I know how many brothers my hero needs and her father's appearance has started to solidify in my head. I'm more certain than ever that I should start my story in the autumn. Like magic, those springtime images of budding flowers and new grasses suddenly become mulch underfoot with orange and gold leaves blustering about on a warm fall breeze.

Time away from the page allows the warring images inside my own self to adjust organically. As I settle in to write again, I'll go back through my first scenes and I'll tailor the words on the page to match the images I now have in my head. I'll likely come across other things that need to be stewed on, but since I'm back from my thinking break and ready to move forward, I'll just highlight those sections and push on. Remember, this is a first draft. I don't need to figure EVERYTHING out now. Just enough to keep me writing.

Do you routinely take timeouts during your writing process? What does that look like for you? Is it challenging when you come back to the page or do you find a renewed sense of energy?

Published on February 16, 2018 04:00

February 14, 2018

Go Teen Writers Live Episode 8: Resubmitting after rejection, character creation, and Wattpad

Hey, it's Jill. I've been working diligently on too many things lately, which means I haven't made much progress overall in any one area. :-/ I'm recording audio books, building storyworld for Onyx Eyes, working on my classes for the Mount Hermon Teen Track, and trying to write my last Spencer book. All at once. I've always been more of a "one project at a time" girl, so this schedule has not been my favorite, nor does it enable me to be my most productive. But in everything there are seasons, and my life right now is no different. So I'm going to continue to peck away and see what I can accomplish. *fingers crossed*

Today, I'm excited to bring you our eighth installment of Go Teen Writers Live! In this video, we answered the following questions:

1) If you query an editor and they reject your manuscript, but you've made a lot of changes, is it okay to resubmit, or is that considered rude?

We talked about how it really depends on what kind of rejection you received, and that sometimes an agent or editor will invite you to resubmit. The one thing you should never do when offered a reason for rejection is to argue with them. Nothing good can come from that.

2) The next question we answered is about how to create characters "from scratch."

This is a complicated question. For several entertaining minutes we struggled to explain how we come up with characters, and then we moved onto the third question, which was about Wattpad.

3) We were asked about Wattpad, and whether or not we think it's a good idea.

Stephanie talked about some authors she knows who were discovered by publishers on Wattpad, and how that's absolutely a thing. But she also talked about how that's really rare, and that's not really the best reason to use a site like Wattpad.

Hope you enjoy the video!

Please feel free to ask any follow-up questions in the comments below. And if you have questions you'd like to have answered on Go Teen Writers Live, email Stephanie at Stephanie(at)GoTeenWriters.com.

Today, I'm excited to bring you our eighth installment of Go Teen Writers Live! In this video, we answered the following questions:

1) If you query an editor and they reject your manuscript, but you've made a lot of changes, is it okay to resubmit, or is that considered rude?

We talked about how it really depends on what kind of rejection you received, and that sometimes an agent or editor will invite you to resubmit. The one thing you should never do when offered a reason for rejection is to argue with them. Nothing good can come from that.

2) The next question we answered is about how to create characters "from scratch."

This is a complicated question. For several entertaining minutes we struggled to explain how we come up with characters, and then we moved onto the third question, which was about Wattpad.

3) We were asked about Wattpad, and whether or not we think it's a good idea.

Stephanie talked about some authors she knows who were discovered by publishers on Wattpad, and how that's absolutely a thing. But she also talked about how that's really rare, and that's not really the best reason to use a site like Wattpad.

Hope you enjoy the video!

Please feel free to ask any follow-up questions in the comments below. And if you have questions you'd like to have answered on Go Teen Writers Live, email Stephanie at Stephanie(at)GoTeenWriters.com.

Published on February 14, 2018 04:00

February 12, 2018

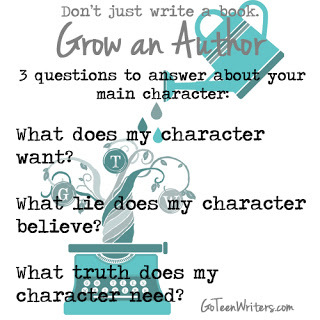

The 3 Questions You Need to Answer About Your Main Character Before You Start Your Novel

Stephanie Morrill is the creator of GoTeenWriters.com and the author of several young adult novels, including the historical mystery, The Lost Girl of Astor Street (Blink/HarperCollins). Despite loving cloche hats and drop-waist dresses, Stephanie would have been a terrible flapper because she can’t do the Charleston and looks awful with bobbed hair. She and her near-constant ponytail live in Kansas City with her husband and three kids. You can connect with her on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, Instagram, and sign up for free books on her author website.

I've always wanted there to be—and have often attempted to create—a step-by-step process for writing a novel. And while there are some things that happen in a clear, orderly fashion, many other pieces feel a bit like the chicken and the egg.

My character forms my plot, but also my plot forms my character.

So even though I've chosen to talk first about my plot and my research, it's not like I cross those off a list before I get going on my characters. The creation process is all very entwined for me, so when I'm working on my blurb or research, I'm also thinking about and working on my characters.

For me, it isn't until I've written my first draft that I feel like I really know my characters. Before the first draft, it's like when there's a person in your life who you've talked to a time or two, but you've never had a shared experience. Yeah, you know them ... but after you go on that mission trip/play that season of volleyball/survive being lab partners, then you know them.

I've tried character interviews, figuring out their Meyer Briggs personality type, archetypes, but none of that has ever served me real well. If you feel like those tools are helpful to you, then stick with it.

The first thing I do, and that you probably do too whether you think about it or not, is mine the story idea for intrinsic character information.

For Within These Lines, there were a few things about my characters that were obvious from the concept of the story. One being that both my main characters, Evalina and Taichi, were the type of people who could be persuaded to break social customs. Since interracial marriage was illegal in California in 1942, obviously dating someone of a different race wouldn't be very popular either. But they haven't told their parents, so they're not rebelling for the sake of making a splash. To me, that suggested that they loved and valued their parents and their opinions.

So just what little I knew about the story has already informed the characters. Before I begin writing or creating a synopsis in earnest, however, I do have three questions that I answer for all point of view characters. I didn't come up with these on my own, I should say. These are craft questions that are so widely taught, I wouldn't even know who to give credit to.

What does my character want?

What are they trying to accomplish during the story? If the goal isn't strong enough, your reader is going to think, "Why don't they just not do this?"

If the authors hadn't done their job in Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Pride and Prejudice, or the movie Tangled, you would think, "Why should Harry Potter look for horcruxes, or Lizzy Bennett wait for true love, or Rapunzel risk leaving her tower?" But you don't because from the beginning of these stories, you know what the main character's goal is, and why.

Because my two main characters, Evalina and Taichi, want a happily ever after with each other, I knew in those early chapters my job was to show the reader how good they are when they're together, and how unfair it is for them to be kept apart.

What lie do they believe, and why do they believe it?

Before the opening of my stories (and most modern stories), my character believes something untrue about his or herself, or the world around them.

The lie is one of the hardest things for me to identify before I write the story, and it sometimes morphs a bit for me as I write the first draft. (Which is frustrating because that inevitably means more work in rewrites.)

When you're trying to identify the lie, you want something that feeds into the overall message of your story ... which means you need to have an idea of what you're trying to say with the whole thing. For Within These Lines, I knew I had a lot of anger over the way the Japanese Americans were treated, a lot of admiration for how submissive and gracious they were through the whole ordeal, and a ton of frustration with how few people advocated for them outside the fences. I didn't really know what my theme would be yet, but I knew those were all topics I wanted to touch on.

Taichi's lie came to me much easier than Evalina's. Taichi's lie is, "If I just do what I'm told, everything will be fine." I knew that lie would feed Taichi's decisions about how to handle cruel treatment from guards and poor living conditions.

Evalina's lie started out as something different, but eventually became, "I'm just a teenage girl." Evalina would lean on her low place in society as an excuse to not speak louder, to not be angrier, to not be more active. She's just one person. What's she supposed to do?

Your characters also need a reason to believe what they believe. Sometimes this is called "an origin scene." For Taichi, I decided he has an older sister who has been very rebellious and gotten into a lot of trouble. From watching her, he learned how to stay out of trouble by obeying. With Evalina, it was a bit murkier to come up with a defining moment of when the lie took hold. I think anyone who has gone through childhood understands that most of the time you feel like a second class citizen who will only really matter once you're an adult.

The best lies for your characters will have truth in them as well. Take Taichi's lie as an example. It's true that if you obey the authorities in your life, things tend to go your way. But what about when the authorities are morally wrong? Or it's true that Evalina is a teenage girl and doesn't have much (or any) clout to her name. But that's not a good enough reason to stay quiet in the face of injustice.

What truth do they need that they'll discover over the course of the story?

Your main character believes they are working toward something specific (and they are) but they also need to be moving steadily toward learning the truth that will defeat their lie.

Evalina, I knew, would have to learn how to be bold and use her own voice even in the face of oppression from someone who "ranked higher" in society. Taichi would need to learn that there's a time and place to question authority.

Once I've answered these three questions—which sometimes happens easily and other times takes trying and trying again to land on the best option—it's amazing how much of the plot starts to take shape in my mind. More on that next week!

Do you do very much to get to know your character before starting your first draft? What tools work for you? What have you tried that hasn't worked?

Published on February 12, 2018 04:00