Diane Lockward's Blog, page 26

May 28, 2013

Gwarlingo and Me: A Love Story

NEWS FLASH: I was the Sunday Poem Gwarlingo feature on Sunday, May 12. Please check it out!

Several months ago I came across Gwarlingo, an online site dedicated to advancing the arts. The site is run by its creator, Michelle Aldredge, who previously worked at the MacDowell Colony but left in 2011 to pursue and support the arts with this new venture. Not surprisingly, Michelle is herself a writer.

What, you might ask, does Gwarlingo mean? It's defined this way at the website: "Gwarlingo is a Welsh word for the rushing sound a grandfather clock makes before it strikes." Michelle strikes a few times a week with posts that feature filmmakers, musicians, novelists, memoirists, and, bless her, poets. Part of her mission is to feature artists who might not have been absorbed into the mainstream, so you can expect to find some new faces and work at the site as well as some familiar ones. All past poet features can be found in the Sunday Poem archive. There is also a complete archive for all artist features.

I came across this site when Michelle initiated her fundraiser, with a goal of raising $15,000, a sum that would allow her to keep the site ad-free. Like you, most likely, I come across a number of fundraising projects for artists. I can't contribute to all of them; nor are all of them equally worthy. But this one struck me as very worthy as the whole idea is to support other artists and to promote the arts. Plus, Michelle offers some enticing rewards for contributions.

Of course, my favorite feature at Gwarlingo is the Sunday Poem. A single poet is selected for the feature which includes a bio, some photos, cover images, excerpts from reviews, and a sampling of poems. This can be read at the website or via email delivery.

Needless to say, I was thrilled when Michelle contacted me for a Sunday Poem feature. Thus I became the featured poet on Sunday, May 12, Mother's Day. What a perfect gift! Michelle chose four poems from my book, Temptation by Water : "Implosion," "How Sarah Wins the Essay Contest," "The Jesus Potato," and "Seventh-Grade Science Project."

If you're not already a subscriber, I encourage you to become one. Simply go to the Gwarlingo site and add your email address to the box in the righthand sidebar. Then you, too, will receive the Sunday Poem and a mid-week piece by email. And if you can make a contribution, please do so. Look for more information at the site, again in the righthand sidebar. Michelle is very close to her goal, but would surely appreciate a bit more help. Should you care to contribute, you'll stand with others who support Michelle's mission to promote the arts. Donations in any amount can be made. But even if you can't contribute, all of the past articles and gorgeous visual work remain available to you. Enjoy!

Published on May 28, 2013 06:51

May 25, 2013

Summer Journals Q-Z

Here's the third and final installment of the list of print journals that read during the summer months. Again, please let me know if you spot any errors or omissions. Good luck!

This mailbox is lucky!

**Remember that the asterisks indicate that the journal accepts simultaneous submissions.

Journal accepts online submissions unless otherwise indicated.

**The Raleigh Review—1x

**Rattle—2x

via email

**Redactions—1x—by email

**Redivider—2x

**Rhino—1x—April 1-Oct 1

**River Styx—2x—May thru Nov

snail mail

**Rosebud—3x

**Sakura Review—2x

**Salt Hill—2x

August 1-April 1

**San Pedro River Review—2x

July 1st to July 31st, 2012 -- Non-themed

via email

**Saw Palm—1x—July 1-Oct. 1

**Slipstream—1x

snail mail

**Smartish Pace—2x

**South Dakota Review—4x

**The Southeast Review—2x

**Southern Humanities Review—4x

via email

**Southern Poetry Review—2x

snail mail

**Sugar House Review—2x

via email

**Turnrow—2x

snail mail

**Tusculum Review—1x

**Washington Square Review—2x

Aug 1-Oct 15

**Weave Magazine—2x

deadline July 31

**Women Arts Quarterly Journal—4x

**Yemassee—2x

Summer Journals A-F

Summer Journals G-P

Published on May 25, 2013 06:47

May 22, 2013

Summer Journals G-P

Here's the second installment of the list of print journals that read during the summer months. If you find any errors or have others to add to the list, please let me know. Good luck with your submissions.

This mailbox is ready to receive lots of good mail.

**Indicates that simultaneous submission is ok

Unless otherwise indicated, the journal accepts online submissions

**Gargoyle—1x—June 1-July 16

**Grist—1x

June 15-Sept 15

**The Grove Review—1x

snail mail

Hanging Loose—3x

snail mail

**Hawk & Handsaw—1x—Aug 1-Oct 1

email subs

**Hayden’s Ferry—2x

**Hiram Poetry Review—1x

snail mail

Hudson Review—3x—April 1-June 30 (all year if a subscriber)

snail mail

**Hunger Mountain—1x

**Inkwell—2x—Aug 1-Nov 15

**Lake Effect—1x

snail mail

Louisiana Literature—2x

snail mail

**Lumina—1x—Aug 1 – Nov 15

**MacGuffin—3x

**Madison Review—2x

Manhattan Review—2x

(prefers no sim but will take)

snail mail

Measure—2x

metrical only

**Michigan Quarterly Review—4x

**Mid-American Review—2x

**The Midwest Quarterly—4x

**Minnesota Review—2x—August 1–November 1

Missouri Review—4x

**The Mom Egg—1x—June 1-Sept 1

**Nimrod—2x—Jan 1-Nov 30

snail mail

North American Review—4x

**Parnassus: Poetry in Review—2x

snail mail

Pinyon—2x—August 1-Dec. 1

via email

**Pleiades—2x—Aug 15-May 15

**Ploughshares—3x—June 1 to January 15

**Poet Lore—2x

snail mail

**Poetry Miscellany—1x—tabloid

snail mail or e-mail

Poetry—11x

Summer Journals A-F

Published on May 22, 2013 06:54

May 19, 2013

Summer Journals A-F

It's that time of year again. During the summer many of us have more time to write and submit, but quite a few journals close their doors to submissions for the summer months. Do not despair. There are still many journals that do read during the summer and some that read only during the summer. This is the first of a 3-part list of those journals, all print. As in the past, several had to be removed this year as they have closed their doors permanently. But a few have been added.

I gave the lists a thorough updating last year and added links for your convenience. If you find an error, please let me know.

This mailbox only accepts Acceptances!

**Indicates that simultaneous submission is ok

Unless otherwise indicated, the journal accepts online submissions.

**American Poetry Journal—2x

(summer only for subscribers)

**American Poetry Review—6x-tabloid

**Another Chicago Magazine—2x—Feb-Aug 31

**Asheville Poetry Review—3x—Jan. 15-July 15

snail mail

**Atlanta Review—2x—deadlines June 1 & Dec 1

reads all year, but slower in summer

snail mail

**Baltimore Review—2x—August 1-Nov 30

**Barn Owl Review—1x—June 1-Nov 1

email sub

**Bat City Review—1x—June 1-Nov 15

Beloit Poetry Journal—3x

**Birmingham Poetry Review—2x—deadlines Dec 1 & June 1

reads all year

snail mail

**Black Warrior Review—2x

Bloodroot Literary Magazine—1x—April 1-Sept 1

snail mail

**Briar Cliff Review—1x—Aug 1-Nov 1

snail mail

**Burnside Review—2x

email sub ok

$3 reading fee /pays $50

**Caketrain—1x

email sub

**Chariton Review—2x

snail mail

**Cimarron Review—4x

snail mail

**Columbia Journal—2x

**Columbia Poetry Review—1x—Aug 1-Nov 30

snail mail

**Conduit—2x

snail mail

**Crab Orchard Review—2x—Aug 27-Nov. 2 (special issue)

snail mail

**Cream City Review—2x

**Cutthroat—1x (plus 2 online issues) July 15-Oct. 1

5 AM—2x—tabloid

snail mail

Field—2x

August 1 thru May 31

**The Florida Review—2x—Aug 1-May 31 (subscribers all year)

Published on May 19, 2013 15:35

May 16, 2013

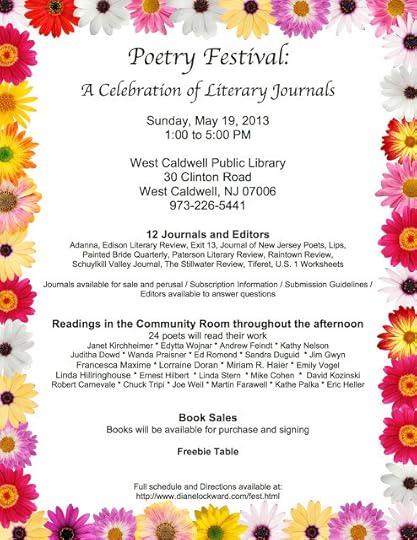

Poetry Festival: A Celebration of Literary Journals

Published on May 16, 2013 06:52

May 9, 2013

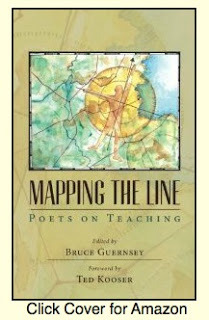

Mapping the Line: Poets on Teaching

If you're looking for some ideas to fire up your own poetry or that of your students, Mapping the Line: Poets on Teaching provides terrific material for poets, teachers, and students. Editor Bruce Guernsey is Distinguished Professor Emeritus at Eastern Illinois University where he taught for twenty-five years. He is also an accomplished poet with six full-length collections, most recently From Rain: Poems, 1970-2010. His work has several times been featured on Ted Kooser's American Life in Poetry column. The poem, Back Road, was featured just this past March.

Following his retirement, Guernsey became the editor of Spoon River Poetry Review. As editor he introduced a regular feature called "Poets on Teaching." That was one of my favorite parts of each issue of the journal.

During his tenure as editor, Guernsey would invite one well-established poet who was also a teacher, one per issue, to write an article about the craft of poetry and to include an assignment that teachers and poets might use. When he left the journal, Guernsey took the feature with him. He has now gathered those articles, as well as some he subsequently solicited, into Mapping the Line: Poets on Teaching. I am happy to be included in this outstanding book and happy to recommend it to you.

The book begins with a Foreword by Ted Kooser. That is followed by twenty essays, covering a wide range of topics. For example, there's "Who's Writing This?" by Cecilia Woloch, "Metaphor as Form" by David Baker, and "Three Exercises for Free Verse" by Wesley McNair. My own contribution is "The Extravagant Love Poem," a discussion of the blazon and anti-blazon with an exercise employing metaphors.

Other authors include Baron Wormser, Kevin Stein, Andrea Hollander, M.B. McLatchey, Robert Wrigley, Doug Sutton-Ramspeck, Guernsey, David Baker, Miho Nonaka, Todd Davis, Sheryl St. Germain, Charlotte Pence, Megan Grumbling, Laurie Lamon, Betsy Sholl, and Claudia Emerson.

Teachers will find this a very useful and informative collection. Poets will find it instructive and inspirational. Students will find that it contains a traveling workshop. This book will be a happy addition to your classroom or your desk at home.

Published on May 09, 2013 06:30

May 2, 2013

The Poet on the Poem: Robert Wrigley

I'm delighted to have Robert Wrigley as my guest poet for this occasional feature at Blogalicious.

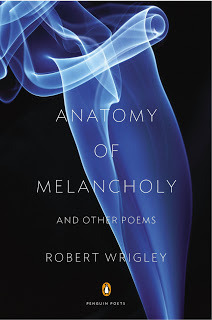

Robert Wrigley is the author of nine collections of poetry, most recently Anatomy of Melancholy. His awards include the Kingsley Tufts Award, for Reign of Snakes; the Poets' Prize, for Lives of the Animals; and the San Francisco Poetry Center Book Award, for In the Bank of Beautiful Sins. He has been the recipient of fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Guggenheim Foundation. He lives in Idaho, in the woods, on Moscow Mountain, with his wife, the writer Kim Barnes. He is the Director of the MFA program in creative writing at the University of Idaho.

Today's poem comes from Anatomy of Melancholy.

Click Cover for Amazon

Earthquake Light

March 11, 2011

Earlier tonight an owl nailed the insomniac white hen.

She'd fluttered up onto a fence post to peer at the moonlight,

to meditate in her usual way on the sadness of the world

and perhaps the hundreds of vanished eggs of her long life here.

I was watching from the porch and thinking she ought not to be

where she was, and then she wasn't, but taken up, a white hankie

diminishing in the east, one the owl would not ever drop.

Now an hour after, the new night wind spins up a leghorn ghost

of her fallen feathers, under the moon and along the meadow grass.

Corpse candle, friar's lantern, Will-O'-the-wisp chicken soul

dragging its way toward me, that I might acknowledge her loss

and her generosity, and wonder again about her long-standing

inability to sleep on certain nights. There are sky lights

beyond our understanding and dogs whose work it is to scent

the cancer no instrument can see. On the nights she could not sleep,

the hen Cassandra Blue perched herself with a clear view to the west

and studied the sky, every two seconds canting her head a few degrees

one way or the other. What she saw or if she saw it I cannot say,

though it seemed that something, always, somewhere, was about to go

terribly wrong. Then again, it always is. Now there's a swirl

of wind in the meadow, spinning three or four final white feathers

west to east across it, and there's a coyote come foolishly out

into the open, hypnotized by feather flicker, or scent, then seeing

by moonlight the too-blue shimmer of my eyes, and running for its life.

DS: Almost every line of this poem contains some kind of musical device. Line 1, for example, has the internal rhyme of tonight and white. The -ight sound is strewn throughout the poem—moonlight, night, might—as are the long i words—Life, friar's, I, sky lights, eyes. There's also a good deal of assonance and alliteration in the poem. Tell us how you create this network of sounds.

RW: Well, there’s no formula; there’s no scheme or discernible pattern. It’s just what I’ve always referred to as writing—which is, for the most part, the only way I’m interested in writing—via sound linkages. My poems, generally at least, work toward sonic unity. As much as anything else, this is the way I learned to make poems, allowing the sounds of individual words and syllables not only to unify the poem but even to determine its progress. Richard Hugo, who was one of my teachers, always said, when the poem requires a decision between music and meaning, always pick music. This doesn’t mean that meaning—whatever that might be; poems mean, but how they mean is vastly more important than what—should not matter. It means, rather, that “picking music” allows the poem’s language to conceive itself into being. And it forces the poet to employ all of his/her resources in order to make the conceptions of the language cohere. In this regard, the sound of the poem, as Frost would have said, is the sense.

I might also say that I have a particular fondness for the musical power inherent in long vowel sounds. Consonants are mostly percussive, and I love percussion. But vowels are notes. Balancing vowels and consonants is the way we make our music on the page.

DL: Talk about your long lines. Did you write this poem in long lines or revise into them?

RW: I write line by line. Always do. And I have to have some sense of the line, however loose it might seem to someone else, in order to see how the poem might move on. As with the sounds of the words, I let lines—and, therefore, line breaks—help determine the poem’s progress toward a unified structure. As I remember writing this poem, I can’t recall ever trying to make that first line be anything but a longish (15 syllables in all) declarative sentence. And that declaration demands elaboration. The verb nailed, and the adjectives insomniac and white are where the poem’s complexity is begun. Nailed, in this context, is a kind of vernacularism for gotten or, in the case of the hen, killed, although it may also be said that Japan was itself nailed by the March 11, 2011, earthquake. White is pretty ordinary, adjectivally-speaking, but it comes into substantial play in the totality of the poem’s imagery. The natural symbolic values of white are exactly what they are. Insomniac is the ringer, if you will; it was for me in the writing. Chickens don’t have trouble sleeping, usually, but animals have mysterious . . . skills and sensitivities. Thus the cancer-sniffing dogs later on. Once I had the first line, I felt the rhythmical contract was established, so most of the subsequent lines have a similar length, both in terms of syllables and stresses. This is also a unifying strategy. Like Frost, I believe the poem is (perhaps even must be) a momentary stay against confusion.

DL: I've noticed that you have an affection for symmetrical verses, i.e., stanzas with the same number of lines and fairly even line lengths. But I've also noticed a lot of variety from poem to poem in your book, Anatomy of Melancholy. What made you choose 3-line stanzas for this poem?

RW: I like the challenge of regularizing, I suppose. Building stanzas that are not only symmetrical but whose construction comes to be a necessary component of how they get said what must be said: well, that’s just one of the many things that might be described as increasing the degree of difficulty in the work of writing. And I’ve always been of the opinion that increasing the degree of difficulty formally or structurally is part of the process of deepening the poem’s complexity. I like to think these particular stanzas may be read vertically—that is, reading only the last word in each line, in three-word increments—and that a sense of the poem’s deeper statement may emerge.

The difficulty of the art is what addicts us to its creation, after all. We become infatuated with the possibilities of that difficulty, the challenge of the problem of the poem’s writing. I do see, looking back at earlier drafts, that, as I closed in on a final draft, the poem was first in six quatrains. Meaning the opening quatrain ended with a period, with her long life here. This would also have been when I noticed the effect of organizing the poem into tercets instead, so that sadness of the world is both the end of a line and the end of the first stanza. That stanza break allows the opening stanza’s final phrase to ring a bit longer, and what else is the poem about but the sadness of a world in which there is often no running for your life—not from owl, earthquake, or fate.

DL: I see another kind of symmetry in this poem, one of content. Tell us about the parallel between the owl and the hen introduced in the first stanza and the coyote and the speaker in the last stanza, the link between Cassandra Blue and the too-blue shimmer of the speaker's eyes, and the shared sleeplessness.

RW: The owl is not malign; it’s just an owl. The coyote, like the owl a predator, is drawn by the scent of potential prey, but it sees the eyes of the speaker in the moonlight, and sensing danger runs off. The too-blue shimmer is a play on blueness, depression, which both the speaker and the hen are afflicted by, for some reason. That the owl’s named Cassandra suggests that her sleeplessness has something to do with a gift (or more likely a curse) for prophecy, even if she knows only that something bad is about to happen. The unspoken presence, of course, is the earthquake, which is also not malignant but merely catastrophic. If there is a greater curse than knowing what will happen, I can’t imagine what it might be. And yet, the catastrophe that befalls the hen is not something, despite her Cassandra-like gift, she can foresee. Unless it is, which is all I think I can say, without saying too much.

DL: Your poem has several metaphors for the dead hen: white hankie, leghorn ghost, Corpse candle, friar's light, will-o'-the-wisp. Do you have a method for getting your brain to unleash these metaphors? Were there any that had to be omitted?

RW: Only that most of them are synonyms for one another: corpse candle and friar’s light being more of less the same thing as will-o’-the-wisp. White hankie as a kind of remembrance, I guess, and leghorn ghost being, for better or worse, chickenish. But the speaker’s role in the poem to this point is thoroughly passive; he’s a witness to the hen’s pondering and to her being killed. When this onslaught of figures comes in, he’s still sitting on the porch, but he’s active in his imaginative re-seeing, a re-seeing that is an endeavor to understand not only what he has seen and continues to see, but, as it turns out, what he will come to know the larger significance of.

DL: I consider a title the poem's first invitation to the reader. Yours is simple but elegant and inviting. Nevertheless, I wonder about its connection to the poem. The dating of the poem suggests some connection to the earthquake that occurred on that date in Japan, but the poem is clearly not set in Japan. Is this another kind of metaphor?

RW: The title came first. This is, almost always, a terrible thing for me. I was probably looking up something else, in a book or on-line, when I came across the phrase earthquake light, and an explanation thereof. It’s a real thing. Mysterious, abundantly theorized upon, and even challenged as myth, it’s something you can look up. There have been many reports of peculiar, seemingly sourceless lights in the sky at or near to areas of seismic, especially extreme seismic, activity. That such a phenomenon is not explainable but has been witnessed is what captured me immediately. The mystery of it appeals to me for many reasons, not the least of which is that I have this sense that there is a similar mystery attendant to the best poems. It’s not just in what gets said but in how it gets said, and that sort of mystery is mythic, bardic, and endlessly sweet to me.

The poem was composed within a few months of the Tohoku earthquake. My wife has had dreams of things happening before they’ve happened. I’ve had one or two. WTF, one thinks. And yet there is something as alive in the earth’s (write it) soul as there is in a poem. A poem written in German by Paul Celan, translated into English by Michael Hamburger, a poem not exactly explicitly stated but still astonishingly, breath-takingly clear: it rings, it resonates, it wallops, in some impossible-to-explain way, what feels like one’s actual soul. That kind of mystery, I mean, in which an insomniac hen may well be aware of or even foresee a catastrophic happening on the other side of the planet. Or perhaps in the vast nervy continuum of chickendom, a Japanese bantam beheld an otherworldly light in the sky, just before the earth itself moved.

Much as I confess I love the word chickendom, I also have to say that I’m honestly and deeply attuned to animals. There’s nothing misanthropic in that. I simply have come to admire the way most animals, especially wild animals, are at ease within their own skins in ways most human beings never are. Of course, Cassandra Blue is both domesticated and anthropomorphized. It may be that her sadness is in that.

***************************

Readers, please enjoy listening to Robert Wrigley read his poem, "Earthquake Light."

<!--

/* Font Definitions */

@font-face

{font-family:Arial;

panose-1:2 11 6 4 2 2 2 2 2 4;

mso-font-charset:0;

mso-generic-font-family:auto;

mso-font-pitch:variable;

mso-font-signature:-536859905 -1073711037 9 0 511 0;}

@font-face

{font-family:"MS 明朝";

mso-font-charset:78;

mso-generic-font-family:auto;

mso-font-pitch:variable;

mso-font-signature:1 134676480 16 0 131072 0;}

@font-face

{font-family:"MS 明朝";

mso-font-charset:78;

mso-generic-font-family:auto;

mso-font-pitch:variable;

mso-font-signature:1 134676480 16 0 131072 0;}

/* Style Definitions */

p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal

{mso-style-unhide:no;

mso-style-qformat:yes;

mso-style-parent:"";

margin:0in;

margin-bottom:.0001pt;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:12.0pt;

font-family:"Times New Roman";

mso-fareast-font-family:"MS 明朝";

mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast;}

p.MsoListParagraph, li.MsoListParagraph, div.MsoListParagraph

{mso-style-priority:34;

mso-style-unhide:no;

mso-style-qformat:yes;

margin-top:0in;

margin-right:0in;

margin-bottom:0in;

margin-left:.5in;

margin-bottom:.0001pt;

mso-add-space:auto;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:12.0pt;

font-family:"Times New Roman";

mso-fareast-font-family:"MS 明朝";

mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast;}

p.MsoListParagraphCxSpFirst, li.MsoListParagraphCxSpFirst, div.MsoListParagraphCxSpFirst

{mso-style-priority:34;

mso-style-unhide:no;

mso-style-qformat:yes;

mso-style-type:export-only;

margin-top:0in;

margin-right:0in;

margin-bottom:0in;

margin-left:.5in;

margin-bottom:.0001pt;

mso-add-space:auto;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:12.0pt;

font-family:"Times New Roman";

mso-fareast-font-family:"MS 明朝";

mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast;}

p.MsoListParagraphCxSpMiddle, li.MsoListParagraphCxSpMiddle, div.MsoListParagraphCxSpMiddle

{mso-style-priority:34;

mso-style-unhide:no;

mso-style-qformat:yes;

mso-style-type:export-only;

margin-top:0in;

margin-right:0in;

margin-bottom:0in;

margin-left:.5in;

margin-bottom:.0001pt;

mso-add-space:auto;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:12.0pt;

font-family:"Times New Roman";

mso-fareast-font-family:"MS 明朝";

mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast;}

p.MsoListParagraphCxSpLast, li.MsoListParagraphCxSpLast, div.MsoListParagraphCxSpLast

{mso-style-priority:34;

mso-style-unhide:no;

mso-style-qformat:yes;

mso-style-type:export-only;

margin-top:0in;

margin-right:0in;

margin-bottom:0in;

margin-left:.5in;

margin-bottom:.0001pt;

mso-add-space:auto;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:12.0pt;

font-family:"Times New Roman";

mso-fareast-font-family:"MS 明朝";

mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast;}

.MsoChpDefault

{mso-style-type:export-only;

mso-default-props:yes;

mso-fareast-font-family:"MS 明朝";

mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast;}

@page WordSection1

{size:8.5in 11.0in;

margin:1.0in 1.25in 1.0in 1.25in;

mso-header-margin:.5in;

mso-footer-margin:.5in;

mso-paper-source:0;}

div.WordSection1

{page:WordSection1;}

/* List Definitions */

@list l0

{mso-list-id:1222446597;

mso-list-type:hybrid;

mso-list-template-ids:1774458560 67698703 67698713 67698715 67698703 67698713 67698715 67698703 67698713 67698715;}

@list l0:level1

{mso-level-start-at:3;

mso-level-tab-stop:none;

mso-level-number-position:left;

text-indent:-.25in;}

@list l0:level2

{mso-level-number-format:alpha-lower;

mso-level-tab-stop:none;

mso-level-number-position:left;

text-indent:-.25in;}

@list l0:level3

{mso-level-number-format:roman-lower;

mso-level-tab-stop:none;

mso-level-number-position:right;

text-indent:-9.0pt;}

@list l0:level4

{mso-level-tab-stop:none;

mso-level-number-position:left;

text-indent:-.25in;}

@list l0:level5

{mso-level-number-format:alpha-lower;

mso-level-tab-stop:none;

mso-level-number-position:left;

text-indent:-.25in;}

@list l0:level6

{mso-level-number-format:roman-lower;

mso-level-tab-stop:none;

mso-level-number-position:right;

text-indent:-9.0pt;}

@list l0:level7

{mso-level-tab-stop:none;

mso-level-number-position:left;

text-indent:-.25in;}

@list l0:level8

{mso-level-number-format:alpha-lower;

mso-level-tab-stop:none;

mso-level-number-position:left;

text-indent:-.25in;}

@list l0:level9

{mso-level-number-format:roman-lower;

mso-level-tab-stop:none;

mso-level-number-position:right;

text-indent:-9.0pt;}

ol

{margin-bottom:0in;}

ul

{margin-bottom:0in;}

--

</style>

<br />

<center>

<embed flashvars="audioUrl=http://montrealprize.com/wp-content/u..." height="27" src="http://www.google.com/reader/ui/35236..." type="application/x-shockwave-flash" width="320" wmode="transparent"></embed></center>

<br />

<br />

Published on May 02, 2013 10:39

April 29, 2013

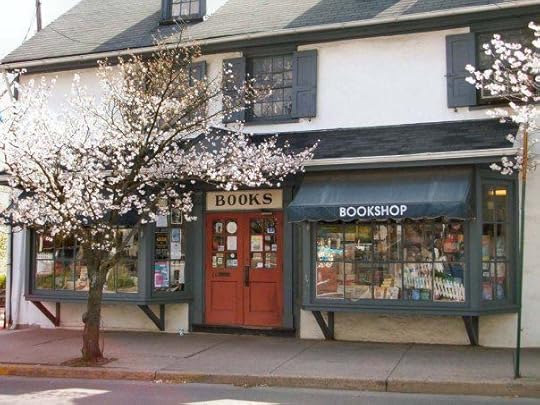

Poetry Reading at Farley's Bookshop

I'll be reading this Thursday, May 2, in the First Thursday Series at Farley's Bookshop in New Hope, Pennsylvania. I've never been to New Hope, but have been told that it's a charming little town filled with artists and nifty shops. If you are in the area, please join me! Here are the details:

Thursday, May 2, 2013

First Thursday Series

Farley's Bookshop

44 South Main St.

New Hope, PA 18938

8:00 PM

reading followed by Q&A

Published on April 29, 2013 10:40

April 23, 2013

Poetry Utopia at the Barred Owl Retreat

Recently I treated myself to a poetry workshop. That's something I haven't done for quite a few years, but I'd been feeling sort of frustrated by my lack of productivity. I suspected that the stimulation of getting away and being part of a group might be just what I needed. I was right. It's now more than a week later and I still feel charged up.

I took the "Two-Day Revision Intensive" with Baron Wormser, a poet I first met at the Frost Place. He has been a mentor to me and an inspiration and a pal. I consider him not only a terrific poet but also an amazing teacher and workshop leader. The workshop was held at the Barred Owl Retreat in Worcester, Massachusetts. The place is owned by Jessica Bane Robert and her husband who purchased it with the idea of turning it into a haven for writers. What a great job they've done in accomplishing that goal. There are several rooms available for participants who choose to stay at the inn. I stayed at a nearby Marriott Courtyard, but was given a tour of the inn's rooms and found them very comfortable and spotless. More rooms are being added. The kitchen downstairs is gorgeous and newly renovated as are the dining room and living room. Most spectacular is the greenhouse room where we gathered both days. What a perfect spot that is! The grounds, too, are beautiful with lots of shrubs, trees, and even a large pond in the back of the house.

Our group of six women poets convened at 8:30 on Saturday morning. A delightful breakfast was available in the dining room along with an endless supply of coffee and tea. We introduced ourselves by each reading one finished poem. Then Baron talked for a while. As he did so, I took down names of poets whose work I need to re-visit—Emily Dickinson, Elizabeth Bishop, Sylvia Plath, Rilke (Letters to a Young Poet), Walter Sutton (American Free Verse—already ordered and in my hands), Denise Levertov on free verse.

Then we went around the circle taking turns with our poems for revision. The critiques were truly intensive. One thing I really admire about the way Baron does a workshop is that I didn't just sit there waiting for my turn. Instead, I learned something from the comments that were made about other people's poems. We got through one round of poems in the morning, broke for a fabulous lunch, then moved on to the second round. I brought two poems which a few months ago I'd thought were finished,

but which had come back each time I'd submitted them. So it had occurred

to me that perhaps they weren't finished. When I learned for sure that they

weren't, I wasn't discouraged but invigorated and excited about

new possibilities.

We worked until 5:30 but were sustained by the delicious goodies Jessica baked for us. We then all went out to dinner together. I returned to my room around 8:30. I would not have thought I could put in such a long day, but I didn't even feel knocked out. In fact, I got right to work on some revisions. I can't remember when I last went twelve hours without checking my email!

The next morning we met at the inn at 8:30. We each found a quiet corner, set up our laptops, and worked on revisions. Again, I surprised myself as I wouldn't have thought I could revise with the clock ticking down, but I did. Baron had suggested that I make my first poem twice as long, so I really pushed it. Not everything I came up with will be retained, but I arrived at some lines and images that gave me pleasure. We gathered again at 10:30 and went over the revisions. Only one of us was able to get revisions for both poems—and that wasn't me. Again, we gave and received good feedback. Nobody yet had a finished poem but everyone went home fired up for the next revision.

Baron had asked us each to bring one extra poem in case we had time, which we did. We spent Sunday afternoon on those poems. We then hugged and parted around 4:00. I stayed over that night rather than make the 4-hour drive home after a long two days. So I had some more time to revise. And that's what I've been doing all week. If you're looking for a place to attend or give a workshop, I heartily recommend the Barred Owl Retreat.

Barred Owl Retreat from the outside

Dining Room where breakfast was served

Our meeting space

Deck off the meeting room

Lunch in the kitchen with Heidi, Carli, Baron, Jessica

Pond in the backyard

Published on April 23, 2013 06:52

April 17, 2013

Lilies and Urine: Perfect Together

I wish I'd written this essay, but I didn't. Pablo Neruda did. It's worth a careful read.

Toward An Impure Poetry

by Pablo Neruda

It is good, at certain hours of the day and night, to look closely at the world of objects at rest. Wheels that have crossed long, dusty distances with their mineral and vegetable burdens, sacks from the coal bins, barrels, and baskets, handles and hafts for the carpenter's tool chest. From them flow the contacts of man with the earth, like a text for all troubled lyricists. The used surfaces of things, the wear that the hands give to things, the air, tragic at times, pathetic at others, of such things—all lend a curious attactiveness to the reality of the world that should not be underprized. In them one sees the confused impurity of the human condition, the massing of things, the use and disuse of substance, footprints and fingerprints, the abiding presence of the human engulfing all artifacts, inside and out.

It is good, at certain hours of the day and night, to look closely at the world of objects at rest. Wheels that have crossed long, dusty distances with their mineral and vegetable burdens, sacks from the coal bins, barrels, and baskets, handles and hafts for the carpenter's tool chest. From them flow the contacts of man with the earth, like a text for all troubled lyricists. The used surfaces of things, the wear that the hands give to things, the air, tragic at times, pathetic at others, of such things—all lend a curious attactiveness to the reality of the world that should not be underprized. In them one sees the confused impurity of the human condition, the massing of things, the use and disuse of substance, footprints and fingerprints, the abiding presence of the human engulfing all artifacts, inside and out.Let that be the poetry we search for: worn with the hand's obligations, as by acids, steeped in sweat and in smoke, smelling of the lilies and urine, spattered diversely by the trades that we live by, inside the law or beyond it.

A poetry impure as the clothing we wear, or our bodies, soup-stained, soiled with our shameful behavior, our wrinkles and vigils and dreams, observations and prophecies, declarations of loathing and love, idylls and beasts, the shocks of encounter, political loyalties, denials and doubts, affirmations and taxes.

The holy canons of madrigal, the mandates of touch, smell, taste, sight, hearing, the passion for justice, sexual desire, the sea sounding— willfully rejecting and accepting nothing: the deep penetration of things in the transports of love, a consummate poetry soiled by the pigeon's claw, ice-marked and tooth-marked, bitten delicately with our sweatdrops and usage, perhaps. Till the instrument so restlessly played yields us the comfort of its surfaces, and the woods show the knottiest suavities shaped by the pride of the tool. Blossom and water and wheat kernel share one precious consistency: the sumptuous appeal of the tactile.

Let no one forget them. Melancholy, old mawkishness impure and unflawed, fruits of a fabulous species lost to the memory, cast away in a frenzy's abandonment—moonlight, the swan in the gathering darkness, all hackneyed endearments: surely that is the poet's concern, essential and absolute.

Those who shun the "bad taste" of things will fall flat on the ice.

Published on April 17, 2013 06:34