Lars Iyer's Blog, page 77

August 7, 2012

The Mask of Loveliness

Older houses. Villa-styled piles subdivided into flats. Victorian houses with pattern-tiled paths and iron railings. Wide avenues with big-canopied trees. Landscaped gardens. The sun flashing on conservatory glass. Peace and calm.

The mask of loveliness, W. says. What does it conceal? The children behind the windows are depressed, he says. The children in their bedrooms are starving themselves to death. They know what Reading is. They know where it is they live.

Builders’ vans. Scaffolding. The bourgeois are extending downwards, into the earth, W. says. They’re putting in swimming pools and home cinemas. But it won't save them. The world will end here as elsewhere. The Reading rich will scream, just as the Reading poor will scream ...

The Eternal End

Reading. The edge of town. Blank-box executive homes, inches apart, five to a plot in place of old bungalows. '70s semis with barn-sized extensions. Driveways packed with Land Rovers and 4X4s.

Mock Tudor houses... Mock Georgian ones, with pebbledash rendering and plastic windows... Great estates with roads named after flowers, after colours, after days of the week... All the styles of history and mocking history. All the styles, and all at once. This is the end of the world, W. says. The eternal end.

The Catastrophe

Reading. The old buildings of the hospital. This is where I was born, he knows that, W. says. This is where I came into the world. He imagines the midwife, holding me up by my heels. He imagines my first bellow, my first cry.

W. reminds me of the story in the Koran. When the first human being was born, a fish came up out of the water, and a vulture came down from the sky. 'The danger has come', they said in unison. The catastrophe! And the fish dived down to the bottom of the waters, and the vulture flew away into the sky.

'Just as man must suffer from God, so God must suffer from man', W. says, quoting Jung. - 'How much do you think God suffered when you were born?'

Transitory Gods

Broad Street, Reading. Office blocks. Glass box buildings.

A crowded south Indian restaurant. Women in saris. Men with masala dosas on big plates. Silver lassi jugs, and big bottles of Cobra. What are my people doing here, in the midst of it all?, W. wonders. They're software engineers, I tell him. Computer programmers, come to work in the Thames Valley. They're following the international flow of capital, I tell him, and bringing India with them.

Pictures of the gods on the wall. A statue of Shiva in dark wood, with a garland of flowers. - 'India in Reading!', W. exclaims. 'It won't last. It can't last'. The Indians will settle down in the suburbs. They'll stop going to the temple, stop celebrating Deepvali. Capitalism demands that! You shall have no other gods than me: isn't that what the international flow of capital proclaims?

Actually, capitalism has its gods, too, W. says. Transitory gods. Appearing and disappearing gods. Isn’t that what we see, flashing on the windows of the company foyers? Isn’t that what is visible on the windshields of the company cars?

A Suburban St Anthony

W. looks through my notebook. Notes on Robert Walser's confinement, he says. Names and dates. Ah, very interesting, W. says. Didn't Walser volunteer to be taken into Herisau asylum? Didn't he want to go there for the peace and quiet? Hadn’t he had enough of the world? Enough of having to make a living. He’d had enough of crowded streets and noisy neighbours. Enough of writing! Of trying to write! Of his will to write! He wanted to give up writing.

At the sanitarium I have the quiet that I need. Noise is for the young. It seems suitable for me to fade away as inconspicuously as possible.

One lies like a felled tree, and needs no limbs to stir about. Desires all fall asleep, like children exhausted from their play.

To fade away; to lie like a felled tree; to be blown around the world like a leaf. What Zen master has ever wanted to achieve more?

Walser wanted to disappear, W. says. He wanted to dissolve into the everyday like some kind of mystic of the ordinary. It’s what I’ve wanted, he knows that, W. says: it’s what I’ve sought in my years of unemployment. Haven’t I wanted to become a man without qualities?, W. says. Haven’t I said I wanted the everyday to smooth away my distinctness like a river does a pebble?

It’s what gives me a strange kind of wisdom, W. says. A strange kind of religiosity! Sometimes, he’s even thought of me as a kind of saint, W. says. As a holy man of the banal; a hermit of the empty hours.

Haven't I been a kind of suburban Saint Anthony: a man who ventured into the deepest of suburban deserts? Haven't I wrestled with the most banal of demons, and passed obscure trials which have left others made or drunk or dead?

What vacancies I have known! What boredoms! What diffuse despairs! The everyday still clings to me like bits of shell to a hatching chick, W. says. It's why, in the end, he has a kind of respect for me. For isn't the everyday the contemporary equivalent of the Biblical desert?

Non-Cosmos

The non-cosmos. The non-ontological. That's what W. sees in my damp, in my rats, the Japanese knot-weed, growing in the yard. That's what he sees in everything I have written and will write. In everything I have said or have tried to say. He hears it in my stuttering. My stammering. In the ‘hellos!’ I boom out to all-comers. And isn't it present in my dancing, too? In my stomach problems? In my ceaseless consumption of celebrity magazines?

Non-thought. Chaos. It's what he hears when I use to the middle voice, W. says. There was a dampening. There was a infestation of rats. There was a proliferation of knotweed. There was and will be writing. There was and will be the desecration of speech.

Faecal emergencies come, one after another. There will be a spattering of toilet bowls. The gods, blind and deaf and mad are screaming. The angels are weeping. The sky is darkening, W. says. The desert is growing. He can smell sulphur, W. says. He can see black wings.

Kurtz is heading upriver... Robespierre is sharpening the guillotines... Lenin is ordering more Kulaks killed... Danton dies again...

Pallasch. Pallasch, Pallasch.

Eternal Seething

In the beginning was the non-Word, W. says; in the beginning, there was no beginning. A kind of eternal seething instead. The licking of black flames. Nothingness turning in nothingness. The void, thickening, and thinning out ...

August 6, 2012

Vote for Dogma in the Guardian Not the Booker prize!

Dog...

Vote for Dogma in the Guardian Not the Booker prize!

Dogma is on the longlist for the award, but now needs to get onto the shortlist. Voting is open until midnight on August 9th.

July 12, 2012

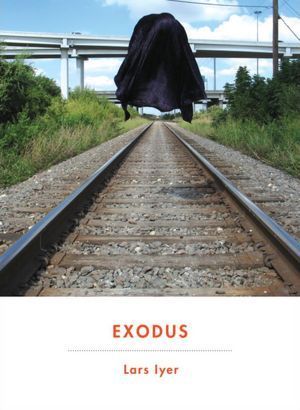

Away until early August. Exodus will be published on 26th...

Away until early August. Exodus will be published on 26th Feb 2013, and is available for pre-order at Amazon UK/ Amazon USA.

The Madman of the Underground

Tottenham, emerging from the underground.

W.’s not surprised that one of the madmen of the underground sat next to us. Did he sense that we had something in common? Did he believe us to be akin, somehow? Like-minded, somehow? He was a religious man, as all madmen are religious. He was an apocalyptic man, as all madmen are apocalyptic.

He spoke of the end of the world. W. nodded in agreement. He spoke of the last judgement. W. affirmed what he said. He spoke of the remnant, of the last stand of the righteous. Yes, said W., a number of times. And then the madman rose and wandered down the carriage.

We musn't be afraid to see our world in apocalyptic terms, W. says. In religious terms. The language of the Last Days is wholly appropriate to our times.

We know what is coming. We know that a new dawn — the opposite of dawn — will spread its dark rays from the horizon. We know that the time will come to put down our pens and close our books ...

Climatic catastrophe. Financial catastrophe. W. quotes the prophet Joel: ‘the rivers of waters are dried up, and the fire hath devoured the pastures of the wilderness’. He remembers what the prophet Jeremiah saw in the ruins of Jerusalem: the earth without form and void. The heavens without light. The very mountains reeling ...

Lars Iyer's Blog

- Lars Iyer's profile

- 99 followers