Lars Iyer's Blog, page 30

May 20, 2016

Five, six seconds and no more - then you suddenly feel th...

Five, six seconds and no more - then you suddenly feel the presence of eternal harmony. Man in his mortal frame cannot endure it; he must either physically transform himself or die. it is a lucid and ineffable feeling. You seem to be in contact with the whole of nature and you say: 'Yes, this is true!' God, when He created the world, said at the end of each day: 'Yes, it is true, it is good'. It is not emotion, it is joy. You forgive nothing because there's nothing to forgive. Nor do you really love anything - oh, this feeling is higher than love! The most terrible thing is the horrific certainty with which it expresses itself and the joy with which it fills one. If it lasted longer the soul could not endure it, it would have to disappear. - In these five seconds I live the whole of human existence, I would give my life for it, the price would not be too high. I order to bear this any longer one would have to transform oneself physically.

Kirilov, in Dostoevsky's The Devils

May 19, 2016

In 1994, my mother had just died. I went to visit my fath...

In 1994, my mother had just died. I went to visit my father on Rue Michel-Ange. I found him on the telephone with Maurice Blanchot.

To my knowledge, this had almost never occurred.

In expressing their mourning, they said tu to one another. The words broke up over their first names: Maurice, Emmanuel. There was between the two of them an inexpressible connection that for thirty years had only been expressed through letters and the dedications of their books.

���Raissa is dead,��� Blanchot was saying. The sentence hung there. It was not necessary to expand. ���Raissa is dead.��� What I heard there was like an echo from the forties. The voice of ���broken and martyred France,��� but the eternal France that my father had always loved.

Standing there next to my father, I then remembered June 1961. Maurice Blanchot was involved in the political battle of the time. June 1961 was the last encounter between Maurice Blanchot and Emmanuel Levinas. I was present, a child hardly twelve years of age.

There had been a great event in my father���s life the previous evening. I was there, too.

It was the thesis defense of Emmanuel Levinas in the old Sorbonne. The Liard amphitheater was full. The French university was getting Totality and Infinity.

On the jury were Jean Wahl, Vladimir Jankelevitch, Paul Ricoeur, Gabriel Marcel, and Georges Blin. In the audience standing very discretely was Maurice, always the friend, the unique and brotherly interlocutor. It was the following morning that Maurice Blanchot came to visit Emmanuel Levinas at his home on 59 rue d���Auteuil. He had, it seems to me, been there several times since the war. This thesis defense of the previous evening marked the end of my father���s institutional isolation. Undoubtedly emotion dominated, too strong. Words were pointless.

What could they say to one another?

I was present for a strange and sublime ���pas de deux��� in that living room on Auteuil, where Totality and Infinity had been written in sorrow.

There was in this room a silent emotion interrupted by attempts at speaking.

The impossible words were fragmented like broken sobs.

There remained only the���tu���and their given names, Maurice, Emmanuel. They paradoxically helped to veil the extreme intensity of the connection, just as they would much later in 1994.

My father stood almost perfectly still in front of the fireplace while Maurice performed a series of scholarly and continuous circumvolutions in that living room.

To the child that I was at the time, Blanchot appeared immeasurably elongated and thin. He was very handsome. He walked with his chest slightly inclined like Giacometti���s L���Homme qui marche.

I felt the bond between the two men. It had been forged at the heart of the twentieth century���s great tragedies and nearly miraculous consolations: the Russian revolution, Nazism and its defeat, and the creation of the State of Israel.

But I could foresee at the moment of this last encounter that the forms of the connection uniting these two men were again going to be radicalized.

Why did this occur precisely on this morning of June 1961, the day after the defense of Totality and Infinity? I would not know exactly how to go about analyzing this.

The speech that carries within itself the inevitable memory of the profane and the dailiness of language became improper to use without betraying, for Maurice and Emmanuel, the infinite complexity of the values of life, of thought. It was a question of leaving intact everything that forged the connection between Blanchot and Levinas since Strasbourg in the 1920s.

That morning in June of 1961 they left one another to pursue this indissoluble connection in a proximity that was still greater for being further away, disengaged from all trivial orality.

They never again saw each other face to face. And that left room for a correspondence that so often was sublime and essential.

Michael Levinas, The Final Meeting between Emmanuel Levinas and Maurice Blanchot [Technically, it wasn't their final meeting - Derrida recalls visiting Levinas with Blanchot in 1968]

May 17, 2016

The meetings of the college [i.e., the Socratic College]...

The meetings of the college [i.e., the Socratic College] took place after dinner every Tuesday (or Wednesday) in the rue de Lille, where Bataille was living. Their theme: Nietzsche. As well as Bataille, there were the five persons mentioned and, not seated like the others, studiously round the table, but sunk deep in an armchair, a seventh and for me mysterious individual whose voice was not heard in the banal exchange of greetings as people gradually arrived. I knew nothing about him. I did not ask him any questions. I did not seem him at Paulhan's, and encountered him only here, scarcely visible in the depths of the armchair. I had no difficulty persuading myself that he must never go out, so pale was his complexion, so white even his wrists. We were all quite thin, our waistlines under the control of a war-time diet. But even compared to us, Maurice Blanchot looked thin.

Bataille began with a brilliant presentation. After a while, you sensed that even the reader himself was perplexed. At first, this added a sort of anxious gravity to our attention. As it persisted, we began to exchange puzzled looks. your neighbours brow began to display a sort of shadow, a blur of doubt. Illumination was a long time coming. Bataille could feel it. Did he lose heart? His delivery became slower. He suddenly stopped.

In principle, the presentation was supposed to be followed by a discussion. But nobody knew how to begin. We stayed silent. Then, from deep in the armchair where he had virtually been forgotten about, Blanchot quiet uttered a few sentences of dazzling brilliance. They restored us to the joy of understanding. We breathed again. So marvellous was the moment that, in order not to spoilt it, we left it hanging by getting up and leaving.

Jean Lescure, cited by Michael Holland

May 16, 2016

- And how many new gods are still possible! As for myself...

- And how many new gods are still possible! As for myself, in whom the religious, that is to say, god-forming instinct, wants, from time to time, to come back to life, how differently, how variously the divine has revealed itself to me each time! So many strange things have passed before me in those timeless meoments that fall into one's life as if from the moon, when one no longer has any idea how old one is or how young one will yet be - I should not doubt that there are many kinds of gods.

Nietzsche, Will to Power, 1038

Every inner and outer occurrence of lunar nights possesse...

Every inner and outer occurrence of lunar nights possesses the nature of the unrepeatable. Every occurrence possesses an enhanced nature. It has the nature of an unselfish liberality and dispensation. Every communication is a sharing without envy. Every giving is a receiving. Every reception inextricably interwoven in the excitements of the night. To be this way is our only way to know what is happening. For the 'I' does not retain for itself any elixir of its past possession, scarcely a memory; the enhanced self radiates outward into a boundless selflessness, and these nights are full of the senseless feeling that something will have to come to pass that has never come to pass before, something that the impoverished reasonableness of the day cannot even visualise. And it is not the mouth that gushes forth but all the body from head to foot, and the body above the darkness of the earth and beneath the light of the sky, the body that is yoked to an excitement that oscillates between two stars. And the whispers we share with our companion are pervaded by an utterly unfamiliar sensuality, which is not some person's sensuality, but the sensuality of the earth, of all that compels our sensibility, the suddenly unveiled tenderness of the world that touches all our senses and that all our senses touch.

Robert Musil, from a discarded draft of The Man Without Qualities

May 15, 2016

I have taken a truth drug and seen through all the lies I...

I have taken a truth drug and seen through all the lies I tell myself. I have laughed so long, so loud, so incurably at myself and all my pompous moralistic self-deceit that I almost died. Every single thought seemed so shallow, so weak so facile, so laughable. Every thought hovered between affirmation and gelation, laughing at itself, laughing so hard at itself, laughing at the thought of laughing at itself, laughing at the thought that this laughter is all there is...

[...] Blasphemy, switching from God to not God and back again became my greatest joke, my original sin... this loneliness, this unattainable outside, meant that I had to die. I had to be crucified, to wake up on the other side in a resurrection.

Aristodemus, in Philip Goodchild's On Philosophy as a Spiritual Exercise

May 13, 2016

It's been a long time, W. says on the phone. It's been to...

It's been a long time, W. says on the phone. It's been too long. He just wanted to say he hasn't forgotten me. He's just so busy. He's never been this busy. He'd retire, if he could. We'd all retire, if we could. Imagine it! A life in retirement ...!

What of our friends - has he heard of them? He hasn't heard from anyone, W. says. He hasn't spoken to anyone, or gone anywhere. He hasn't got time. He's like me - in infinite purdah.

What about the arts? What has he seen or heard of note? He has no time for the arts, W. says. He's too numb for the arts.

I tell him about the apocalyptic economics programmes I've been watching. Things are bad! Very bad! The next crash ...

When is the next crash?, W. asks.

In 1998, Wall Street bailed out a hedge fund, I say. In 2008, the central banks bailed out Wall Street. Well, in 2018, the IMF will have to bail out the central banks ...

Will there be cannibalism?, W. asks.

There could be hyperinflation. There could be a run on the banks. We have to buy gold! It's the only thing that's safe!

He likes my economic turn, W. says. - 'Is that your new line of flight: economics?'

Anyway, he's going to send me the next part of his Gottesbuch, his God book, W. says. - 'You'll like it'. It's handwritten, he says. It's written entirely in propositions, like Spinoza. He'll send me a PDF.

I make enthusiastic noises.

'And it's in different colours', W. says.

More enthusiastic noises.

'I knew you'd like that', W. says.

May 12, 2016

Car driving is a religion. Modernism as a whole resembles...

Car driving is a religion. Modernism as a whole resembles an arena, a self-contained circuit. That's why Formula One races are so important. They are the modern proof of what St Paul the Apostle wrote: the godless go round in circles. The circular rides in the circus contradict the elemental hope, the key theme of the modern age: the primacy of the journey out, opening up new spheres. If technology is the perfect control of sequences of movement, this leaves us with only one progressive function: braking.

[...]

... the culture of soul journeys begins with the observation that individuals can lose their souls. In depression some people become separated from the principle that animates them[...] Shamanism became important here because they know the art of looking for the depressed person's lost free soul somewhere at the edge of the world, and bringing it back to its owner. The early movement experiments and shamanic soul journeys were meant to revive the alliance between humans and their animators, that is, their companion spirits, the forces that help to arouse enthusiasm[...]

... the car is a machine for increasing self-confidence. The difference is that an external engine causes the movement. The car gives its driver additional power and reach. I think we have to see the vehicles of humans in the first place as a means of idealization and intensification, and consequently as a kinetic anti-depressant[...] Two our of three movements are escapes: people drive to their lovers, they take trips to the countryside or on holiday, they go visiting, or they use the car for letting off steam. We could almost think people use the car as revenge on the heavy demands of settledness.

Peter Sloterdijk, Selected Exaggerations

May 9, 2016

I cherish what Thomas Bernhard does, but in my view it is...

I cherish what Thomas Bernhard does, but in my view it isn���t literature.

Ah yes, Thomas Bernhard, the room-clearer of Austrian literature. ���His suggestive power consists in his ability to exploit and assemble prejudices. It affects me like an article from Der Spiegel. I often think he is our best Spiegel correspondent in Austria. Because the things he writes don���t tackle problems of narrative or form at all, they seem to me to be having an almost detrimental effect on art. I found his last few books to be almost criminal in their shoddiness. Apart from his suggestive power, which of course is unique to him and always extremely effective, there was nothing there. But in his new book, Extinction, I am suddenly seeing the rudiments of description, of enthusiastic description of locales and spaces, which for me is of course the most important thing in literature. Otherwise it is of course difficult not think of this drama about the lord of a castle as [Ludwig Ganghofer���s 1895 novel] Castle Hubertus, only with a negative spin. But I was cheered and relieved by those descriptions of the orangery or of the kitchen, because I was able to enjoy a feeling of parity. Of course I wish I could approve of him; I have indeed revered him for 25 years as a kind of secular Austrian saint.

Handke on Bernhard, from an article in 1986 (letter 501 here)

April 19, 2016

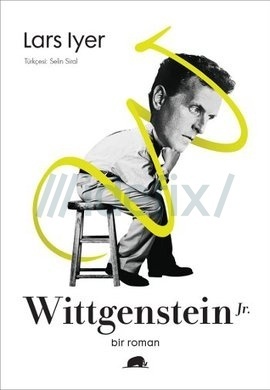

Wittgenstein Jr in Turkish:

Lars Iyer's Blog

- Lars Iyer's profile

- 99 followers