David Gessner's Blog, page 92

March 3, 2012

R.I.P. Mighty Waddles: A First-Class Rooster

Our beloved rooster, Mighty, a handsome barred rock, has died. He started life as a chick among chicks, but slipped on newspaper bedding (we didn't realize that newspaper is too slick for chicks), damaging his feet early on. And then, we noticed, he was far smaller than the other birds. We babied him, thought him a girl. Elysia named him Carmen, as he sang a lot more than the others. About the time the pullets began laying their first eggs, we noticed that Carmen was growing. Soon, he was the biggest bird in the yard, half again as large as everyone else. He grew a magnificent plume of a tail. And he grew spurs at his ankles. And with those sharp thorns he came after us when we went to tend the coop. With them, he held the dog, Baila, at bay. He mated with the pullets, frequently, a process that looked like a stomping and a squashing, but which is known in ornithology circles as a cloacal kiss. His carriage was erect. His wattles were elegant, but froze some in winter. The feathers of his neck were subtly layered in black and white. He was a one-man op-art painting. Elysia renamed him Mighty Waddles: that foot injury. Soon, however, he was merely Mighty. First to the food! Last out the door! Irritable as my mother on a bad day, 1967. He'd peck at the ground threateningly to let you know he saw you. Don't fuck with Mighty! Under his feathers he had tattoos. One was an anchor, another was a handgun. BORN TO CROW across his chest. The dog thought the protection was a game and played with the cocky bastard for hours on end. Matter of only a few months, Mighty just stood by while Baila sniffed his butt. They began to share the dog yard peaceably, the kind of barnyard friends you see in cartoons. (Once I looked and saw Baila sleeping in the grass, Mighty standing watch.) If I didn't deviate from the normal

Mighty at six weeks: Still Carmen

coop tending, he left me to my chores. But if I so much as hesitated, he'd come after me. Occasionally he'd sneak up behind. He bit my hand twice. He ripped my blue jeans with his spurs.

But only once. Because, well, I kicked him clear across across the pen I'd built. He came back after me and darn if I didn't kick him across the pen again. That was enough. Pecking order established.

I started carrying a broom to remind him who was head rooster, patted him with it friendly, but also patted him where I wanted him to go, steered him this way, steered him that, kinda fun. He was remarkably strong.

Like the rest of us, Mighty mellowed in his late months. If he heard talking, he flapped his wings and crowed. Any commotion at all, he crowed. He crowed the dawn. He crowed the dog barking. He crowed the mailman. He crowed all comers. He crowed when I put the barn light on,

middle of the night. But it wasn't a very loud crow, and never annoying, not like I worried when we first figured out who he was.

The other morning, a cold one, I found him dead. Just like that. Not the first bird we've lost, and not the last. But the first rooster. The invincible rooster. He crows for thee. The Mighty protector, always between his hens and danger. No idea what got him. Illness? Apoplexy? There may have been an encounter with a fox, some private injury. We'll never know.

And we'll never forget! Goodbye Mighty, goodbye. You weren't even three years old. Mighty, we hardly knew ye.

The newest chicks come April 26, just six of them, and with luck, one will be a cockerel. We may increase the odds by adding one un-sexed chick to the order. Once, we thought we didn't want a rooster. But a rooster is a great friend to have.

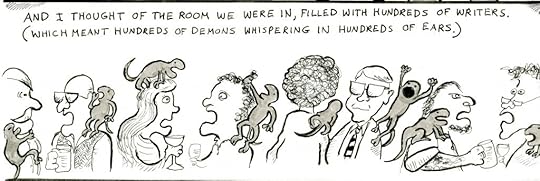

Live Report From AWP…….

It's noon at the AWP (Association of Writers and Writing Program) in Chicago. I start drinking again in about an hour. This is just another way that AWP is not like my normal life. In my normal life I go to bed at 9:00 and get up at 5:00. In my AWP life I go to bed at 2:30 (and get up at 5:00). In my normal life I don't drink 3 vodka martinis and talk to hundreds of writers. In my….well, you get the point.

This morning I thought I had a panel on Thoreau at 11. I was up and ready to go when I finally looked at the program and found out my panel was actually at 9. I asked someone what time it was and it turned out it was 10:01. My panel ended at 10:15 and I was staying a mile away from the hotel. Kind of a nightmare….I had flown out here and would miss it. But no! I sprinted for a cab, told the driver to step on it, ("Hurry, man, I've got to talk about Thoreau!") and then sprinted into the panel with five minutes left. Turned out that was enough time for me to quote Thoreau a few times–"The life that men praise and call successful"–tell some jokes and, despite my slamming heart, not die of a heart attack.

Now it's fish and chips with some fellow writers and then the boozing begins again. Then, thankfully, it will be back to my normal life.

March 1, 2012

SUMMERS WITH JULIET is Twenty

Summers with Juliet, published February, 1992

Summers With Juliet started as an idea for a personal essay, one of my first ever (before that I'd only written formal essays and fiction), nothing more than this: My not-yet wife and I had seen an enormous fish in Menemsha Pond, Martha's Vineyard, a sea sunfish, Mola Mola. One January day I started to write that story, and by late March, I finished it. After a year of revising and enriching the thing (while writing other stuff, of course), I sent the essay off in the mail. The Iowa Review published it, and "Mola Mola'' eventually got an honorable mention in The Best American Essays, 1991.

Well, hey. I decided I was on to something, and wrote another piece—I considered what I was doing nature writing—about a great blue heron. Then another, about some blue crabs. My grad-school friend Betsy Lerner read them, kindly, and said the thing she liked best about them wasn't nature so much as that Juliet was there in all of them. Men usually left their women out of their nature writing. She thought there was a book in there. She even had a title for me: Summers with Juliet. And then she helped me connect with a great agent. Later, much later, she became my agent, but that's another story.

So: a collection of nature essays in which Juliet played a role.

Juliet now, with a new character

My new agent–Binky Urban at ICM–asked for a couple more and an annotated table of contents to describe the unwritten ones. She gave me ten days to do this. She was testing me. I did what she asked. She like one of the new pieces, tossed the other, formed a proposal, messengered it to ten or so top editors and sold the book on the second day out, to Houghton Mifflin.

I was kind of happy. Then I had to do the work. It took a year.

When I'd finished the seventeen essays that made the first draft of the book, everyone said to tie them together. And gradually, that's how the structure of Summers With Juliet emerged. That structure is self-consciously classical: three acts—situation, development, denouement (this last is from the French, as you know, for untying).

Act one comprises six scenes (I should say "scenes,'' since each is a chapter in itself, and some freestanding essays): "Hot Tin Roof,'' "Berkshire Turkeys,'' "Cross Canada,'' "Volcano,'' "Bluefishing,'' "Turtles.'' The situation: a callow young man (myself) in love with a young woman not impressed. A romance develops despite obstacles, mostly of the young man's making. The last scene ("Turtles'') ends with his realization that his own growth is required, and the arc of the narrative rises to act two.

In act two, which is comprised of "Out of the Frying Pan,'' "Hummingbirds,'' "Callinectes Sapidus,'' "Mola Mola,'' "Fishing With Bobby,'' and "Canyonlands,'' the situation (the romance) is developed in a series of tableaux, each built around a carefully nested central metaphor, each metaphor growing nearly absurd (especially when said directly, as will follow): Juliet is a wild trout in an unfished stream; Juliet is a bossy bird; Juliet is an elegant crab; Juliet is an ungainly and rare fish of enormous proportions; Juliet is a gawky heron; Juliet is dangerous as a snake and as big as the canyons of Utah. Or perhaps the word love should replace the name Juliet above: Act two has grand pretensions. Ends with our boy's resolve to marry.

Juliet in 1982, Martha's Vineyard, Age 20

Now, while I was about knitting my various essays together into a book (we'll get to act three in a minute), I realized that Summers With Juliet was doing something subversive: standing up to the boys from the cult of the expert and messing up the central mode of a traditional form—Nature Writing (yes, so self-important is the form that it must be capitalized). Which central mode is that a man goes alone into the wilderness and finds transcendence, glory, absolution, expertise, and so forth. As the central figure in his own autobiography, he finds his way to nothing less than him-ness (or Him-ness, if he gets to God, which is the Emersonian model). It's a male figure made countlessly by male practitioners over centuries, a particularly American figure: I faced the wilderness alone, made peace with it, and in that way conquered.

Bill that same summer (too much sun)... Going on 29

All I really had to do to subvert was to introduce a woman. And make her and her feminine contempt for the rites of the male my foil and my catalyst (because they were in life). To end the book with a wedding was to complete the subversion: Male autobiographies have not, historically, ended with weddings.

Act three, our conclusion: "Water,'' "Visitors,'' "River of Promise,'' "Bachelor Party,'' "A Wedding on the Water.'' The situation having been developed to an almost ecstatic height, our narrative arc begins its fall. The young man, now well feathered, bathes his beloved in an act of devotion, struggles with fear (again the trope is at work, everything to be read as an examination of love with its subtext of mortality), climbs a mountain to ask for her hand, goes fishing with his best man in Central Park (a reprise, a look back, a caesura), then is wed.

The book was published in February, 1992. I can hardly believe it has been twenty years. But it has.

Juliet and I met in July, 1982. Thirty years this summer. She was twenty.

February 29, 2012

Bad Advice Wednesday: Be Like Nixon!

This may seem like really bad advice at first….be like…Tricky Dick? Of course he is starting to seem less creepy in a world of Santorums and Gingrichs and Ws…..But still plenty creepy.

This may seem like really bad advice at first….be like…Tricky Dick? Of course he is starting to seem less creepy in a world of Santorums and Gingrichs and Ws…..But still plenty creepy.

No, I am not suggesting that Nixon should be your moral model, just that he had one habit that comes in handy when you are a writer. The guy taped everything.

For my part, I use a Sony micro-cassette recorder, and this recorder has become an integral part of my writing life. My goal is to re-create my voice on the page. What better way to do that than to actually re-create my voice?

Be warned that it can be an awkward tool at first. I quickly got over the whole "I don't like the sound of my voice" thing, but back when I started, over two decades ago, you looked a little crazy if you talked to yourself in public.No more of course, as we rush about, all chattering to ourselves like a nation of schizophrenics. So you'll fit right in–they'll think it's a phone. But another problem was the pomposity factor. Think of the Alan Alda character in Woody Allen's "Crimes and Misdemeanors," talking into his tape recorder: "Brilliant idea for a scene…"

A larger challenge is to start to actually compose on the tape recorder, since most of us associate composition with privacy and typing/writing. This takes a while but it can be thrilling once you realize that your rhythms speaking into the machine can be almost exactly like your rhythms while writing. My original use for the recorder was to simply remember things–chapter titles, good lines, snippets of dialogue I overheard. I still use it to this end, and, like Nixon, I tape other people when they talk (though I ask). In writing My Green Manifesto, I jutted out the tape recorder (snug in a ziplock bag) across the canoe to record Dan Driscoll as we paddled down the Charles River.

But more vital, for me, are the long walks I take with dog and tape recorder. Sometimes I'll pose myself some simple questions when I start the walk: Where should the next chapter go? How does this concept of wildness versus control fit into the essay? Why does this section feel claustrophobic? But I never try to answer them directly, letting the walk take care of that. Then when the words–and sometimes the answers–start coming, I break out the recorder.

Often enough these sentences, spoken out loud, become a rough draft for what I'll later write at my desk, without even re-playing what I've recorded. But just as often, maybe more often, I get some good stuff, and as I transcribe it from the tape I fiddle with the sentences, which means the process becomes, in effect, another draft. And on a very rare occasion I will speak an entire essay onto the tape. That is what happened with "A Letter to a Neighbor," an essay which I published in Orion magazine. The occasion for this essay was a dawn walk below our neighborhood bluff on Cape Cod when I looked up to see the foundation and skeletal beams of the massive trophy house being built. I was filled with love of the place and anger about the house and out came the essay, whole, right onto the tape.

One final advantage of this sort of composition is that it offers a change of pace after hours at the desk. "A change is as good as a rest," said both Churchill and Lady Grantham. For me walking is a great writing rhythm. Legs move and words come. It was Churchill's preferred mode of composition by the way, and, after a long day of politics, painting and partying, he would head to his study and dictate a few thousand words to his team of transcribers. I don't have a team, but my trusty Sony Micro works fine.

So be like Nixon. Sweat a lot, lie, never fully shave. And tape things, too.

February 27, 2012

Table for Two: An Interview with Michael Martone

Michael Martone

Recently I got a postcard from Michael Martone announcing his newest book, Four for a Quarter. Beneath several vintage-looking photo strips, the postcard and book cover show an old photo booth tucked into a tattered post-no-bills wall somewhere in post-industrial America. The booth sports a sign that says PHOTOS, of course, but it took a little staring to notice that the designer (Lou Robinson) has inserted the word FICTIONS in a font so much the same size as PHOTOS that at first (and then for several weeks) I didn't notice it. It's as if the booth sold PHOTOS FICTIONS. But the fictions referred to are Mr. Martone's. The book is nicely made, beautifully printed and presented, kudos to the The University of Alabama Press (and a notation that much of the great literary work being produced these days is being picked up by university and other small presses).

.

Four for a Quarter is a delightful book on the page, as well, a stream of meditations, of stories, of collectibles, of comedy, of tragedy, of every possible thing grouped in four. Or it seems every possible thing until you walk away and find the world falling into infinite fours, yet another organizing principle and OCD tic to contend with.

Four for a Quarter

Michael is the father of the alternative literary magazine bio, in which he tells a continuing story of his life and alternate lives via the normally prosaic 100 or 150 words they give you in the likes of Epoch, or The Iowa Review, or Iron Horse, in all of which and hundreds more Michael has published his work.

The two of us have agreed to pretend to meet for a meal and talk about Four for a Quarter, among other things.

BR: Where should we eat? I thought of the Four B's in Helena, Montana, which is a lunchroom, basically, good French fries. Visiting during my high-school years, I'd eat there with my Aunt Kay who was a window dresser in the department store nearby. Then, of course, there's the Four Seasons in New York City, midtown, a little more upscale.

MM: I like the idea of The Four Seasons–designed by Phillip Johnson yes?–who is mentioned in the new book.

BR: His glass house is in New Canaan, CT, where I grew up–we used to scale the high stone wall to see if we could see him in his pajamas. Ah, but here we are. The Four Seasons. 99 East 52nd Street. And in we go. The bar is one of the most beautiful I've ever seen. A good place for a bottle of wine.

MM: … and in the Seagram Building designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

BR [Under his breath]: Note rare four-word last name, and that the first clause of this sentence is all four-letter (but clean) words.

MM: … one of the initial international style buildings where the structure is the style, form turned inside-out. And a glass box to boot!

Maitre d': We've a four-top reserved in the Pool Room.

BR: Which, as our readers can't see it, is very lovely, a square pool with a large tree growing at each corner.

Maitre d': Your table, gentlemen. Please don't get too abstract. [He hands us menus, which are broadsides beautifully printed.]

MM [sitting]: Back to the word "table."

BR [ditto]: Of course.

MM: I was once asked to contribute some entries to a dictionary addressing things that until the book were unnamed. I used the word "table" to define two processes often found in New York. The first was when a group of friends discuss where the group will go to eat. I thought that could be called "tabling" (the extended nature of the process has a nice echo to the legislative notion of tabling) and the other end of the event when a group settles up the bill. Being the Midwesterner I always would purchase cheaply, anticipating the each would pay his or her own portion but inevitably after "tabling" the bill would be split evenly. Again, the haggling over the check echos the other bill in legislatures. I hadn't thought of those definitions in years.

BR: Are you sick of people coming up with fours? It's such a temptation after reading your book. In fact, for me it has become an obsession.

[The waiter arrives, and we order]

MM: I am not sick of folks coming up with fours. The number, of course, has been with me for a long while–I started writing it when I was 44 and only stopped when the 44th president was elected and the first-class stamp went to 44 cents. I am still amazed there are so many and that people find more. I had always thought that there were more threes or twos. In the way back of my mind there was the book LETTERS my teacher John Barth was writing when I was in grad school that depended upon sevens. Those numbers seemed more likely to generate a long list of subjects. No, I have liked living with fours and still find it an interesting nothing to meditate upon.

MM: I am not sick of folks coming up with fours. The number, of course, has been with me for a long while–I started writing it when I was 44 and only stopped when the 44th president was elected and the first-class stamp went to 44 cents. I am still amazed there are so many and that people find more. I had always thought that there were more threes or twos. In the way back of my mind there was the book LETTERS my teacher John Barth was writing when I was in grad school that depended upon sevens. Those numbers seemed more likely to generate a long list of subjects. No, I have liked living with fours and still find it an interesting nothing to meditate upon.

[waiter drops off our bottle of wine, a rare Carraine from Chateau les Quatre Filles]

BR: John Barth! I loved Letters, all those missives between his characters regardless of century rocked me. 1979, right? I'd been a big fan of The Sot-Weed Factor, all that swiving in colonial Maryland. There'd been a long hiatus in Barth's career. And suddenly here those people I'd loved in (extracurricular) high school were writing letters to characters in later books and to Barth himself, wonderful. I hadn't yet discovered Laurence Sterne and no one had ever tried the phrase post-modern on me and here I was on the road with this or that rock band reading while everyone else slept and feeling in the presence of something entirely new and fresh. And he was your teacher?

MM: He was working on LETTERS when I was writing my thesis at Hopkins. I didn't know he was writing LETTERS, and in conference one day I told him the title of my thesis. Numbers. It was the only time I saw this very formal, very stately, and very brilliant man taken aback. In LETTERS, as you know, there is a character who is writing a book called NUMBERS. And here I was, a fiction manifest before him.

BR: This wine.

MM: LETTERS got a first page review in the NYTBR which said something like this is the tombstone of literary modernism. It signaled in 1980 a profound and instant change in the landscape of fiction in America. Raymond Carver calling for "No more tricks." The dominant mode switched overnight from formalistic experiments like LETTERS and surreal or irreal fictions to narrative realism that has now been dominant for the last 25 years or so.

Waiter [Presenting our first small plate]: Like the fiction you write, Mr. Roorbach.

BR [inhaling the fragrances gratefully, hint of sage]: You under-read me.

Waiter: I don't read you at all.

MM: … Only recently has that dominance begun to change. Barth told me when I was a student that I didn't write stories. He was right. Technically I did not write stories. I don't write stories but fictions. He was fine with that, of course. I learned that stories were just another form. That, I think was the thing I learned from Barth. All is artifice. Artifice is all. And I had to master as many forms of writing fiction as I could.

BR: I read the pieces in Four for a Quarter as poems, as flash fictions, as flash essays, as found objects. Then again, there are some longer pieces, reaching four or more pages, such as "The Teakwood Deck of the USS Indiana," clearly  a story, as well as pieces that are developed as essays, though sometimes grouped with stories. "The First Four Deaths in my High School Class" reads as nonfiction, poignant. Your use of language throughout the book would make everything here easy to describe as poetry, and in fact some pieces could easily be at home in Poetry Magazine. How do you read the pieces here, or want them read? One piece is called "Tessera," and it is, in fact, like a tile or other more irregular fragment in a mosaic.

a story, as well as pieces that are developed as essays, though sometimes grouped with stories. "The First Four Deaths in my High School Class" reads as nonfiction, poignant. Your use of language throughout the book would make everything here easy to describe as poetry, and in fact some pieces could easily be at home in Poetry Magazine. How do you read the pieces here, or want them read? One piece is called "Tessera," and it is, in fact, like a tile or other more irregular fragment in a mosaic.

MM: And the Greek word for Four. That particular piece is very much a mosaic, a collage, but not one that makes a whole picture when pieced together. The bits are connected by these other abstract coincidences. Funny, that in stories, the narrative depends upon a huge coincidence to get the story started–the "one day" that sets the set-up in motion–but then the story seeks to hide all the accidents, force a more logical cause and effect. A story, too, never never wants to end in a coincidence, not if it is a realistic story. O. Henry, yes. Or Twilight Zone twist. No gods in machines. But this is a lyric "story" and its narrative is abstract. It is all about, for me, association, random association that is all about randomness and accident and coincidence. Where the naturalistic realistic story seeks to hide the artificial, a story like this emphasizes the artifice. So all the pieces don't come together to form a picture as much as to picture the material itself. This is a mosaic that pictures a mosaic. You are forced to look at the individual stones as individual stones and then make the larger grouting moves. I love the pictures of Chuck Close who paints individual abstract pictures that when connected on the larger scale create a super realistic portrait. How to do that with words instead of paint? Things to look for here in this story. There is blood. Blood everywhere. There are four basic blood types. Greece of course. Myth and mythic tales. I am very interested here too in animating characters who become artists or artists who become characters. Thucydides had to write his own part of the story in his history. Achilles transforms from the warrior to the storyteller telling the story of his transition from woman to man. Now that I think about it, these stones are meant to reflect different frequencies of light. Heroes turned into regular Joes. A poet and a first lady reduced to their bodily fluids. All about the sublime. Changing states is the change here more than changing character.

BR: What challenges did you face in structuring this material?

MM: I am sure that what I just said about Tessera sounds challenging. I am not sure why I am wired to associate, to find connections in very random elements but I am. It's not hard for me to structure. Structure is what the structure is all about. I am conscious about resisting the existential nature of language to line up. Words want to become narrative. They have naturally a beginning, middle, and end of the line. The challenge for me is to break it up, to disrupt what the written language wants to do on the page. It tends to the narrative. The challenge for me is to use that medium without the bias. Perverse, I realize. I figure that is the challenge for a reader who wants story, that thread out of the maze, not just the maze. Yes, I build mazes but I'm not a very good Ariadne. The clews of yarn I supply are pretty clueless.

BR: This makes a great bathroom book. I mean that as a compliment. I could keep reading it in reiterative increments pretty much forever. When should I stop?

MM: Well, I'm not sure you should though I suppose there is a time limit on actually occupying the bathroom. But not the book. I like to think that all of us have just one book we write, are writing. A big job for the writer now is keeping the book alive and in print. Think Leaves of Grass. This new book contains pieces previously published in books of a different title, in magazines, delivered at readings. In the same form or slightly altered. I like to have in my stories the sensation that these things, this writing is alive, organic, growing, changing in different contexts, frames, delivery devices. You never step into the same bathroom twice!

BR: Heraclitus.

MM: I want to design my one book to be a book that is read forwards and backwards and back again. I want it to feel as you are reading it that it is still being written. Or that it is being erased. Or that the reader is writing all over it. There was that wonderful hypertext memoir that launched a virus when you began to read it that literally erased the text. A book about memory forgetting itself. Frank Gehry said of his house in Santa Monica where he used all the materials of construction–plywood, chain-link fencing, sheet metal, etc–to finish the structure that he wanted it to feel still in process, to feel as if it were being edited. I am all in to the dead author side of the argument. I am not the authority of the texts I create. I don't have the sole stake in the making of meaning. I know I am collaborating with the reader. I provide the interesting pieces (I hope) and the reader takes it from there. The reader writes the book. So no I wouldn't want you to stop.

BR: I can't, not to worry.

[The food comes. It is good. Our budget is $444 each, so no worries there, more if necessary, the nice thing about pretending.]

MM: I just saw in The New York magazine that The Four Seasons is ranked number 52 (up from 56) in their annual rating of the top 100. It mentions the ridiculous prices–$55 for a crab cake–but does recommend the bar lunch at $35.

BR: Not for us, not today.

MM: If I may quote: "… this plutocrat watering hole still manages to retain its special Oz-like feel." So we may not be in the 1% but maybe at least the 4%! The reason I get New York Magazine is funny. My grandfather gave me what he thought was a subscription to the New Yorker, thinking I was wanting to be a writer and so would like the magazine. He made a mistake and sent New York. I have been a subscriber to it all these 30 years or so. Never subscribed to the New Yorker though I did own shares in the company when it was still traded publicly. When the magazine was bought out, I made more money on the tendering of the stock than I have ever made selling fiction. But that is another story.

BR: My mother got New York, too, I think because it had a good puzzle… I wrote an article for them once about death and ever since people introducing me will mention the New Yorker, not true, not true, but you can't start a reading by saying you didn't really have work in the New Yorker… Is Fore Street on that list? It's in Portland, Maine, and I think the best restaurant I've ever eaten in.

MM: It was just NYC places. Of course. I love Fore Street. My wife, Theresa Pappas, went to school in Portland and lived there for awhile and for a long time we did summer in Maine. I love it. We have to get back there. I love the Italians of Maine–the real cuisine of Portland not lobster rolls. Theresa worked a bit an LL Bean and her second book of poems is called The Desert Art and many of the poems are about the Desert of Maine. Great postcards from there.

BR [Spooning a scallop bisque]: But I do love a good lobster roll. And a great clam shack. So long as the bathrooms are clean.

MM: The question about toilet reading also got me thinking about the James Wright poem that ends with "I've wasted my life." Poetry is fond of putting pressure on such words as waste, forcing a reader to inflect till the cows come home. Has the poet wasted his life or has this man wasted his life by not being a poet? The perfect suspension in that hammock. Rock above the tropic earth. Poetry too makes nothing happen. I want in this book about a bunch of nothings make those nothings happen. I want you to waste your time on this earth.

BR: I really love the postcard captions you've collected and present in the book. Here's one called "Four Found Postcard Captions," and the postcards happen to be from the Wadsworth-Longfellow House in Portland, Maine, where I've been with my daughter.

[Reads]

1.

This most historic house in the State was built in 1785 by Major General Peleg Wadsworth, grandfather of the famous poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, who spent much of his life here.

2.

The Boy's Room was occupied by all the Longfellow boys at various times. Here the Poet wrote his first poem. Here also is the old trundle bed and the scarred school desk.

3.

The Rainy Day Room. Its chief interest is in the old desk on which the Poet wrote, in 1841, "The Rainy Day." "It rains, and the wind is never weary."

4.

The Guest Room of the house contains the four-poster bed and rocking chairs of the General's wife, Elizabeth. To this room the Poet brought his bride, and here, later, the Poet's father died.

Waiter [checking in on us]: That was lovely.

BR: Indeed. And there are a lot of really delectable tidbits here of all kinds. Michael, what's your method of collecting material?

MM: Somewhere, I read, Donald Barthelme wrote that he wanted to be on the leading edge of the junk phenomenon. I love that idea. I think some writers are writers of nouns. Most live in those active verbs, in the predatory predicate. You asked about collecting material but I know you were thinking of the "material" in the abstract. As writers we must be by nature abstractionists who wrestle those abstraction into the "concrete" conventions of writing. I love stuff. I collect a lot of things. I just wrote a piece about my thermos collection of all things. http://www.hungermtn.org/list-5-micha... I think we are seeing more and more writers expand their notion of writing into the realm of the material nature of things. It is hands on from here on out. Die-cut books, books in boxes. The writer because of the changing nature of the means of production the way books and magazines are made finds him or herself involved in what we used to think was the designer's job, the publisher's job, the editor's job. I like postcards a lot. I of course collect postcards, arrange them into stories. "Writing"a postcard is an act of publishing. And I love being involved in not only the abstract writing of the message but the concrete manipulation of the material. The stamps. The writing instruments. And the post office contributes the cancellation, the bar codes of routing. There is so much to read–other than one's own writing– on the card. So many texts. In museum school there is an argument between those curators that want to deploy labels with artifacts and those that don't. I like a third way of thinking about it. The labels themselves are artifacts that can themselves be labeled, even expanded.

BR: What should writers be trying to do now that everything's broken?

MM: Well, they certainly shouldn't be trying to fix it. Broken is good. As you might guess I would say to take those broken pieces and put them back together in a new way. And then break them again. Art is about rearranging the known. About re-framing the deranged. I worry at times that the cultural moment we are in as writers–namely the movement into the university for poetry and literary prose–subtly forces us to fix the broken instead of break the fixed. The university's impulse is curatorial by nature. It finds a bunch of bones and puts them back together and then teaches its students to put the bones back together in the same way. To maintain, to store, to study, to norm. All of these are important activities but not activities that art should be about. I want to generate new genera and that is very difficult in the setting that seeks to categorize and sort. The university can be thought of as a vast efficient storage facility. But you were asking about what should writers try doing. Funny you should use that word. I edited an anthology a while back of new fiction called Trying Fiction for Colorado Review. Yes, I like the pun. The attempt and the difficulty both. Writers should be trying. Writers should try to be trying. Should try to try one's patience.

BR: Tell me about your career.

MM: I was very lucky. After graduating from Indiana University in 1977, I returned home to find my parents had sold my bed. I was an English major with no job so I slept on the couch. I out-smarted my parent's gambit in a few weeks when I found a job as a night auditor in a hotel in Fort Wayne. I walked in and told the manager that I was a liberal arts major and I knew nothing about accounting but I could be taught. And she bought that. The hours were from 11 to 7 in the morning. I would come home then after my shift, and roll into my younger brother's bed as he rolled out of it to go to high school. I think I thought that the third shift at a hotel would be easy. A long stretch where I could write and read but it turned out that the third trick in a hotel is one of the busiest. I did love the job. And it gave me time to write in the daytime poems for hire in a downtown park. I charged a quarter a poem, on any subject. Over the noon hour, I'd make $5 or $6. Tax free! And write 20 poems or so. This was a stunt developed at IU with a bunch of friends. We called ourselves RKO Radio Poems. A poem must not mean but be 25 cents. Hey there is the early inkling of the book right there. If you have ever seen the film Breaking Away, we were there outside the stadium writing poems for hire for the crew and the extras. I would suggest everyone do a stint as a night auditor. The job is very interesting but the hours are hard. The consequence of that is there is always a night auditor job listed in the classifieds. More?

BR: More.

MM: I published the first two books, little chapbooks of very short prose, myself with a little help from a Fort Wayne small press called Windless Orchard this was in the late 70s and the work was mostly things that I wrote for folks in the park in downtown Fort Wayne. Very local meditations on Fort Wayne and Indiana. I really mean I published them myself too. I used a typewriter and rub-on lettering and Xerography and mimeography.

BR: Rub-on lettering! Extinct now, of course, along the mimeograph (except in inner city schools and many English departments) and so much other writing technology.

MM: … Then I went to grad school at Hopkins where I wrote a book, of stories called Cardinal Numbers. Odd to think back on that now, what with the new book Four for a Quarter. Cardinal numbers was a book of ten stories each based on a number. My first hardback book was Alive and Dead in Indiana. I had been writing a mythology or that's what I thought it was. Edith Hamilton, the great popularizer of the Greek mythology (which I loved) grew up in my town and i wanted to dramatize the myths of Indiana and record them in a series of monologues. Gordon Lish came to Ames, Iowa to give a reading and said to everyone there to send him stories. So I did and he actually took the lot and had me write more for a book!

BR: What was the path to Four for a Quarter?

MM: I see now that the seed for this book was in those early days of thinking about Indiana, numbers, monologues, and non-narrative lyric forms. I don't think of myself as a novelist but I have always thought of myself as someone who makes books. When you are also not much of a story-teller and give up the narrative pattern you have to impose some arbitrary pattern to sustain length. I often just use numbers. If I had been born later in the digital age instead of the analog one I would say that what I do is just invent algorithms to solve the problem of structure in my prose. That is what we all do I know. We pose problems for ourselves to solve in the performance of writing. I just seem to have always done that in terms of numbers. I was the generation that was taught the "New Math" for the first time. Sets and bases. Sixth grade. Price Elementary School. Mr. Flora.

BR: How has parenting affected your writing, both on the practical end–getting to your desk, or wherever–and on the daydreaming end?

MM: I love what William Stafford told writers who came to him saying they were blocked. "Can't write? Lower your standards!" Having children teaches you to actually lower your standards. As a parent you learn quickly it is about imperfection. Or the calculus of approaching perfection but never coming to it. What amazed me was childbirth itself. Birthing since we are now so removed from it, from this human animal moment, struck me as so interesting and absurd and wonderful from a writer's point of view. There were all these competing narratives. My wife imagined the births would go this way. The doctor had her competing narrative. The nurse another. The birth assistant another still. And then me. And all of us reading books about birthing and watching movies and telling stories or hearing stories of birth. Amazing. Anyway, one can "write" this moment up in all these different scenarios and yet the moment when it does happen simply writes itself. Control means to roll against. Birth of my babies, the raising of the babies, taught me to roll with and that, in turn, taught me that I am in less control than I think of the stories I write.

BR: Love that, "roll against."

MM: I find I think of myself as an arranger of things now more than the author of things. Improvisation is important in life and in the writing. I try to say yes to the things that are given me and then add and. Yes! Yes and…

BR [forgetting entirely about the restaurant trope]: You've taught at the University of Alabama for some years: How does that work with your writing and thinking and being, in general, a writer?

MM: Yes? I teach writing in a generative way now but in an institution that is rigorously curatorial. I have been fortunate at Alabama to be able to clear a space for the students to do lots of things and not worry so much about being professionalized. Try things. Discover self and art. It is a gift I can give. None of the students here pay for the schooling. I don't make any promises as to what they will do or become. I just say come here and write with me. Let's find out what writing is for you. Let's make something up. My standards are so low. I don't feel like I am a police teacher protecting writing from amateurs or dabblers or those who are simply no good. My students have expressed a profound interest in writing. I let them write what they want to write. I guess I am a flakey artist. I have embraced that. I am far more interested in quantity of writing than in quality. Not at all interested in critical thinking–there are plenty of teachers around here for that. I tell my dean when he inquires after my goals for writing that successful outcome would be in twenty years my student will still be writing. How can we assess that he asks. I tell him in twenty years we will have to ask.

BR: Tuscaloosa had a terrible bout with tornadoes this past fall, and the University was clobbered. What was that like?

MM: I was at school teaching when classes were canceled. There at been storm damage in my neighborhood that morning. I drove back home from school through streets already blocked by felled trees from that morning. It would have been safer to stay at school and have my family come there. I drove west into the storm as it came on. The tornado that then hit was further south in the city and sliced up from the southwest going northeast. A very straight line so unlike most tornadoes. It was a half-mile to a mile wide. Many of my students were much closer than I to the destruction and they were immediately in it and out in it helping. I kept power and was in touch with them through the rest of the day through their cell phones, email and Facebook. What was very frightening was watching them go dark as time went by and their batteries drained. Like the stars going out. Perhaps that is the most disturbing aspect of this disaster. It is the first one I have ever been in with all this electronic equipment. All the cell phone pictures, the video you-tubing real time reports. All the information everywhere but here. Friends and family watched the storm happen in real time. Stranger than strange.

BR: And more than disruptive. What's your writing routine like, if any?

MM: I have been writing for 40 years–hey there is another 4–and I am one of those writers whose routine is not to have a routine. I think this habitless habit really developed when Theresa and I had the first baby. I got really good at writing in the seams of time, the writing time filling space between the spaces of the not writing time. It was at that time too that I began thinking, more and more, that all writing, all kinds of writing, "counts." That is to say, I don't think that working on this interview is subordinate to the mail art text I am also writing right now in another window on the desktop.

BR: But we're just having dinner.

MM: … I write a lot of postcards when I travel. I count that as writing.

BR: I count gardening, hiking, skiing, this meal.

MM: Letter writing. Journal keeping. Note taking. Blurb writing. Notes in the margins of students' stories or essays. That spills over to the "real" writing I do do. I don't think my stories are the most important thing. Or the essays. There is just the great big differences. The adaptations of the writing to time and place constraints. I did this anthology–and I think the anthologies I do where I arrange other people's words as important as the books where I am arranging my own words–where I asked writers for their writing rules. We called it Rules of Thumb. And I loved it because there were all this different accommodations with space and time that each writer had worked out and each was convinced that this was the way it had to be done. What is the name for that kind of dance exercise where you just keep running bouncing off of buildings, leap-frogging mailboxes, swinging around street signs, tumbling and falling and getting back up? What is that called?

BR: Singing in the Rain?

MM: That is my routine. Just to make way. You know that from sailing up there in Maine, right. A sailboat must "make way." And once way is made then anything can happen.

On the Netting and Tagging of Babies

I net and tag Hadley. She is 4 weeks here, the optimum age for radio collaring.

I understand why some people are against netting and tagging babies. But the crucial issue here, I hope you understand, is control. We simply can't have babies running wild over the marsh and through the woods, going hither and yon, completely unmanaged. In the end the goal is to protect babies and to protect them, ultimately, we need them to be tagged and tracked. I would think this would be obvious, even to the lay person.

If I seem insensitive, please understand, that I know of what I speak. We first trapped and tagged my daughter Hadley in the salt marsh behind our house in East Dennis. My wife argued that she should develop on her own, freely, and that we should release her without the radio collar. I tried not to laugh at her lack of scientific discipline. Softened by her maternal instinct, she did not understand my hard reasoning. How could we protect the newborn without a radio collar? How could we follow where it went? How could we study it? And, perhaps most importantly, how could we use what we learned to advocate for wild babies in the future?

I tried to explain that the collaring process was relatively painless, but, again soft-hearted, my wife could only hear the child's screams. "She won't even notice it once she is back in the wild," I said. "It looks heavy," she said. "Only 23 ounces," I said.

In the end she saw the sense of it. This are modern times after all. We can't have wild, un-monitored babies roaming about. Don't you agree?

February 26, 2012

Oscar Degrees of Separation

Siedah Sings To Hadley

As far back as the cave humans no doubt took satisfaction in what Samuel Johnson called "imagined connections to celebrity." ("By the way, I know the chief's brother.") I am not above this guilty pleasure myself and can tell a "I did cocaine with Tim Robbins at the Howard the Duck cast party and talked about our future writing lives while the two midgets who wore the duck suits ran around and before hitting on Lea Thompson and yelling at her when she turned her nose up on me" story with the best of them. (True story by the way–for another post.)

And so now, at Oscar time, I will not focus on dull categories like "Best Picture," but on the much more interesting "People We Want to Win Because They Have a Connection to Dave."

Obviously Clooney and I go way back and have both faced the burden of being dashing 50 year olds, but George has gotten enough press this week.

Let's instead start–and why not–with Siedah Garret, who is up for Best Song for "Real in Rio" in the film Rio. Here are some Bill and Dave reasons we want Siedah to win:

1. Her vastly underrated album, Siedah, was my daughter Hadley's favorite album, and the only way you could get Hadley to sleep was to walk her up and down while blasting songs like "Get the Hell Out of Here."

2. At the time the album came out she was going out with my oldest friend Dave, and when I met her she was funny, generous, blunt and dynamic. I suspect that hasn't changed.

3. It makes sense for her to win for a song in a kids movie since I know she likes singing to kids. That's her in the picture above singing songs from her album to a two month old Hadley.

4. The movie has a lot of birds in it. Ditto the song.

* * *

As well, as rooting for Siedah we are pulling hard for Best Adapted Screenplay for The Descendants. Why? Because it's a fine movie, well-written and literate? Well, sure there's that…..but really it's because Kimi's brother wrote it. That's Kimi Faxon, writer, teacher, friend. Her brother co-wrote the screenplay along with his regular co-writer, Jim Rash, and director Alexander Payne.

We will be rooting hard for Nat tonight. But with no disrepect to Nat, Kimi is still our favorite writer in the Faxon family. Check out "Personal Belongings, in the anthology Choice: True Stories of Birth, Contraception, Infertility, Adoption, Single Parenthood, & Abortion which according to Eli Hastings, "will rip you asunder and piece you back together."

Here's a pdf of the essay: kimi hemingway.

February 25, 2012

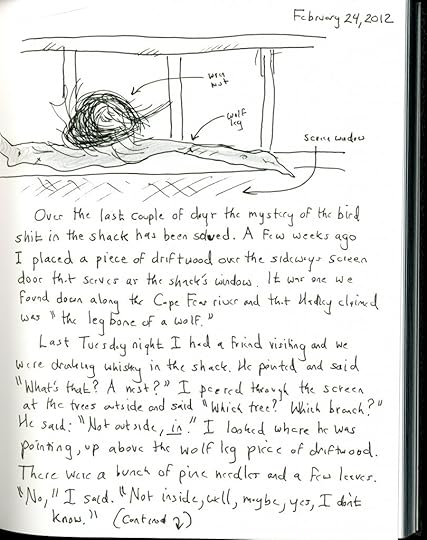

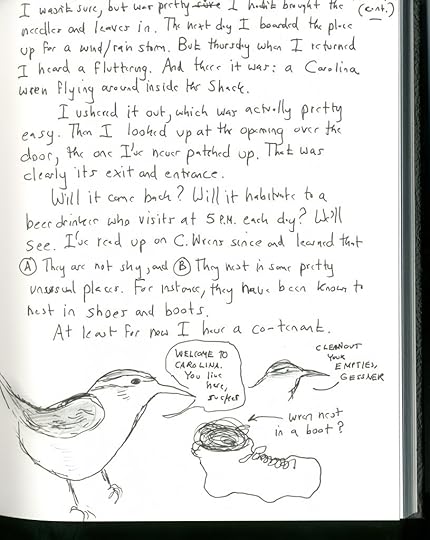

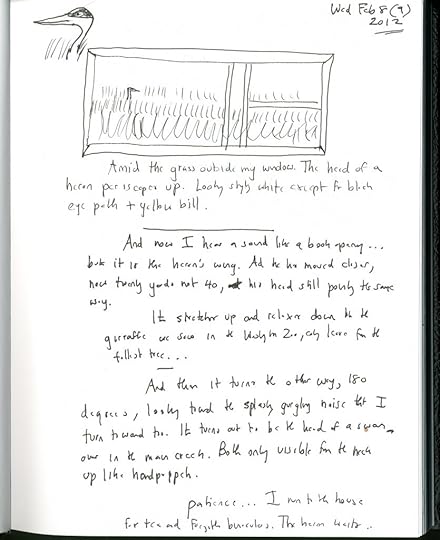

Getting Outside Saturday: Some Recent Journal Pages…A Mystery Solved

February 23, 2012

Trouble in Happy Valley: Penn State, Joe Paterno, and the Art of Fracking

I spoke at Penn State on Monday. My hosts couldn't have been more generous and engaging, but my thoughts weren't always peaceful ones. First, there was all the fracking going on up north in central PA, which seemed to call for a cartoon. Here it is…..I call it….

THE FUTURE OF GROUNDWATER

What follows are some random observations (and pictures of me with Paterno's statue….)

Joe Pa and Me

As I flew into the Happy Valley this past Sunday, I felt rather uplifted. After a non-winter winter in North Carolina, I was actually tired of green. I saw snow on the ridge lines, countless small farms, and enough open woods to put the lie to the more hysterical environmental cries of doom. But I'm a literary sort and so remembered that in Samuel Johnson's Rasselas the title character never quite could find peace, even in a perfect world called Happy Valley.

Later, looking up at the statue of Joe Paterno, another literary allusion came to mind (one I began to work out on this blog a few weeks back). I remembered The Brothers Karamozov, and the story of the beloved priest who was hero and mentor to the pious Aloysha Karamozov. The elder lead a devote life and had even been considered a possible saint, but then in death his body had rotted and stank, which was seen as a physical embodiment of a deeper corruption. Hadn't something similar happened to Joe Pa, who for most of his life was seen not just as a great football coach but as the moral conscience of the game, and certainly the presiding saint of the town of State College, Pennsylvania? That Paterno had played his part in the unspeakable tragedy that occurred here did not take away my sense of life of effort, passion, and commitment torn down at its end. And my sense of a town stripped of its illusions.

Less Reverent Pic

I spent the next couple of day's with a couple of other vital, if less celebrated pillars of the community. They were Penn State professors and the picture they painted was grim. Over the last couple of years the governor had been trying to cut the University budget by 50%. They did not need to describe for me the damage this would do to education, of course, but what struck me was all the jobs that would be lost. And something else was rotten in central Pennsylvania. This same governor had refused to tax the energy companies that were busy hollowing out the hills to the north, fracking away and then rumbling off down the state roads in their huge trucks.

I imagined one of my heroes, Wallace Stegner, rolling over in his grave. In envisioning an ideal town he had always said that a college should be at its center. This led to what he called "stickers," people who made the town their own. In contrast, he held up "boomers," people who come to a place, extract what they can and then leave it behind, hollowed out. When jobs are touted we had better ask ourselves what kind of jobs those are? "To hell with schools and others fancy pants institutions," seems to be the rallying cry. But wouldn't education come in handy in the coming economy? Never mind, they seem to say. The jobs that matter most are the temporary ones.

Something rotten indeed……

Farewell, Happy Valley

February 21, 2012

Bad Advice Wednesday: Beginnings

Today's guest post is by Kyle Minor, author of In the Devil's Territory (Stories). He's at work on The Sexual Lives of Missionaries (a novel). And he's an all-around good guy. Like Bill, he works all night.

.

Beginnings

I. Bad Advice

At Bill and Dave's Cocktail Hour, when someone offers "bad advice," the advice that follows is usually pretty good advice. The phrase "bad advice" is armor, because you know how it goes. First, you offer good and useful advice, and then somebody gives you the one example of why the greatest story anyone has ever read would be a terrible story if the writer followed your good and useful advice. And then somebody else puts on a black beret and lights a cigarette and talks about how all true art is boundary-breaking, and all true artists would never accede to the tyranny of conformity. Then the open mic night begins, and somebody starts beating the bongos, and somebody else yells abstractions into a microphone and uses the word "poetry" a lot. Three friends in the front row say, "This performance really flows," and the four drunk guys at the bar watch the basketball game, which is, let's face it, the better of the two shows.

If you ask me, as Bill and Dave have asked me, to offer some bad advice, I'm not going to give you "bad advice." I'm going to give you some seriously bad advice.

So here's some bad advice: Start all your stories in the middle. Start a scene without worrying about managing information in a way that helps your reader fall into the fullness of the point of view from which the story arrives. Don't let the reader know who the speaker might be. (Better, yet, don't know for yourself who the speaker might be!) Don't let us know where we are or when we are. Don't bother to establish the story's ground rules. If we're on the planet Jupiter, and our lovers are a swarm of gnats who breathe methane and know they'll die the first time they profess their devotion to another swarm of gnats, don't let us know that until page 14 of the 15 page story.

As a bad lover might, begin with the climax. Get it out of the way in the first ninety seconds. Be sure to stop the forward motion of the story near the top of page two, and then spend five pages doing the necessary exposition that helps us understand what we just read on page one. Don't attend to the music language makes in the first sentence. Consider opening in unattributed dialogue. Consider attributing the dialogue to a speaker with a first name – Frank, or Joe, or Bob, or Mary – and don't bother to let the reader know who Frank or Joe or Bob or Mary might be. Quickly introduce a second speaker with an equally generic name – Martha, maybe – and don't bother to let the reader know the relationship between Frank and Martha. If they are sisters, don't let us know that they are sisters until page seven. If they are lovers, page eight. If they are mother and daughter, page nine. If they are mother and daughter and they are also lovers, page eleven.

Don't get quickly to the trouble (http://www.gulfcoastmag.org/index.php?n=2&s=2607). Let us first hear about the weather. Describe the characters by their faces or the color of their hats. Do a lot of gestural stuff—smiling, winking, nodding, arm-crossing. When we do get to the trouble, be sure that we start with a single-character scene where a character is alone in a room and crying about something that happened to her which we haven't yet seen. Do a lot of interior monologue full of the language of felt emotion. Use abstract words like angry, happy, sad, love, exhilarated. Stick an -ly on these

Kyle Minor

words and be sure to get them into your dialogue tags. "I am so happy," Mary said exhilaratedly. "Me, too," Frank snorted uproariously. "Me, three!" Martha ejaculated spently. What a happy family they be!

Don't avoid the impulse to make extraordinary generalizations. ("All happy families are the same," Mary, Frank, and Martha said winkingly.) Don't avoid the impulse to do any essaying your story might require at story's beginning rather than story's end. Don't hang out with the kind of people who do the kind of work your characters do so you might know at story's beginning that our dentist, Dr. Hewitt, would use the D-11 Root Extractor rather than a pair of tweezers to retrieve the shard of decayed tooth root he broke off during the extraction. (Let's be fair: He was distracted. He bought this dental practice and the building that housed it from vain old Dr. Green, who painted the walls green in tribute to his own name, and no matter how many times Dr. Hewitt paints the walls white, a ghastly green tint peeks through. Why didn't Dr. Hewitt negotiate more vigorously? Why did he overpay by $100,000 for this third-rate practice and this building with these goddamn green walls?)

.

II. Good Advice

.

Here's some good advice: Read everything. Pay close attention to how your betters are beginning. Build up a catalog of borrowed opening gambits. Note the relationship of point of view to time. If the first person narrator is offering a dispatch from the moment, and we don't have a latter-day narrator to offer helpful expository runs, how does the writer compensate in offering the baseline information the reader needs in order to understand the first moment in the same way the speaker understands the moment? If our speaker is very old, and the story itself is therefore about all that has changed—all the possibilities now turned to what-if-I-hads—how, then, might the story signal that the reader's greater patience with all the heavy-lifting will be rewarded with a corresponding pleasure?

How does the story manage the givens particular to time and place, which form the ground rules by which the characters understand the world and make their decisions? If we say that the story of Romeo (age 20, let's argue) and Juliet (age 13), set way back when in fair Verona, is about star-crossed lovers whose love is fated to tragedy because they belong to incompatible rival families, then what happens if we signal good and early that our Romeo and Juliet is set in Toledo, Ohio, in the year 2012? Does the reader then know that we have a statutory rape story? What if we don't establish time and place until page 20? Will the reader turn to page one, and read again the first twenty pages in light of the new and necessary information, or will the reader throw the book across the room in frustration?

Is it too much, to talk about all these things as abstract concepts? All right, then. Call down a parade of books from your shelves. Say: "Dance for me, baby. Sing." It's like a Broadway audition. Hundreds of thousands of fresh-faced singer-dancers are ready to offer their songs, but the harried old casting director, who has already seen it all, doesn't have time to hear the whole song. Not everybody's whole song. The only people who get to sing the whole song are the people who don't hit one wrong note, make one wrong step, but that's not all. Lots of our auditioners are technically proficient. There's something else the casting director requires, too: A big chance, taken. A special quality of voice and movement. The promise of something visceral or cerebrally pleasing or otherwise new. The spark of life.

Five minutes ago, I gave this a try. See now the parade of my pretties, and the notes I made about them in my notebook of do-or-die:

1. Openings simply establishing who speaks and/or when and where we are in space and/or time:

"William Stoner entered the University of Missouri as a freshman in the year 1910, at the age of nineteen." – Stoner, John Williams

"When I am run down and flocked around by the world, I go down to Farte Cove off the Yazoo River and take my beer to the end of the pier where the old liars are still snapping and wheezing at one another." – "Water Liars," Barry Hannah

"I am Gimpel the Fool." – "Gimpel the Fool," Isaac Bashevis Singer

First, note the efficiency with which this strategy dispenses with the offering of necessary information. (This is why newspaper journalism has kept to the convention of the dateline, and why magazine journalism so often embeds the dateline in the first sentence.)

Second, note how little this strategy has to do with voice or speaker. Those are elements independent of the structural gambit, which is to open in the most clear manner possible. The voice of the speaker makes other kinds of promises about the story we're about to enter. We know, right away, that John Williams is about to offer us a stately, measured, and plainspoken account of the life of William Stoner, something not unlike a biography. We know, right away, that Barry Hannah's narrator will be a yammerer, possibly an exaggerator, a gather-round-the-campfire-and-let-me-tell-you-a-tale-son sort. And we know, right away, that our Singer's Gimpel is going to stare his trouble straight in the face, and we trust and love him for it.

2. Expository openings whose primary purpose is to introduce us to the trouble at story's beginning (and these often also include the matters of who speaks and/or when and/or where we are in space and/or time):

"Of the twenty stallions brought to Cap Francais by the ship's captain, who had a kind of partnership with a breeder in Normandy, Ti Noel had unhesitatingly picked that stud with the four white feet and rounded crupper which promised good service for mares whose colts were coming smaller each year." – The Kingdom of This World, Alejo Carpentier

"For the first three years, the young wife worried that their lovemaking together was somehow hard on his thingie." – "Adult World (I)," David Foster Wallace

Again, could these two speakers be any less alike? The elegance of Carpentier's language elevates story and speaker, as does the choice to fill the first sentence will stallions and the breeder in Normandy and the ship's captain and the stud with the four white feet and rounded crupper. It's all there – sex, death, colonialism, grandeur. We expect an epic sweep. And the corresponding inelegance-unto-artlessness of Wallace's language – the young wife, "their lovemaking together," "somehow hard on his thingie" – signal a colloquial and near-to-our-ear speaker and a no-bullshit account of something that might seem small unless you're in it, and then it might well be the most important thing in the world.

What both sentences share, as opening strategies, is a great clarity. Both stories go on with the exposition for awhile longer, but in either story, if the scene began in the second sentence, we'd have enough information to be ready to enter into the scene without scratching our heads and wondering what the hell is going on.

3. Quick-to-scene openings (sometimes expository, but they signal that they won't be for long) whose primary purpose is to introduce us to the trouble at story's beginning (and these often also include the matters of who speaks and/or when and/or where we are in space and/or time):

"I was coming down off the Mitchell Flats with three arrowheads in my pocket and a dead copperhead hung around my neck like an old woman's scarf when I caught a boy named Truman Mackey fucking his own little sister in the Dynamite Hole." – "Dynamite Hole," Donald Ray Pollock

"The child had been warned. His father said he would nail that rock-throwing hand to the shed wall, saying it would be hard to break windshields and people's windows with a hand nailed to the shed wall." – "Gentleman's Agreement," Mark Richard

"Lizard and Geronimo and Eskimo Pie wanted to see the scars." – "Miracle Boy," Pinckney Benedict

Here are three openings that work in a very similar way to the Wallace and the Carpentier openings, but they also have a special speed to them which the brevity and compression of their short stories will require. In the Pollock opening, note the change from the first part of the sentence to the second. We open with a passive-ish construction ("was coming") which smartly embeds motion in it, and by time we get to "when I caught a boy named Truman Mackey fucking his own little sister in the Dynamite Hole," we've already upshifted to a more active register ("caught . . . fucking.") Note, too, the way Pollock offers us much about the narrator-protagonist by way of what he's carrying ("three arrowheads in my pocket and a dead copperhead hung around my neck like an old woman's scarf.")

4. In Medias Res:

"Strike spotted her: baby fat, baby face, Shanelle or Shanette, fourteen years old maybe, standing there with that queasy smile, trying to work up the nerve." –Clockers, Richard Price

"The gun jammed on the last shot and the baby stood holding the crib rail, eyes wild, bawling." – The Plague of Doves, Louise Erdrich

"He wanted to talk again, suddenly." – "In the Gloaming," Alice Elliott Dark

Here are three stories that open in the middle. (Remember: You can do anything. Even open a story in the middle.) They each must undertake the special challenge that all stories that open in the middle must undertake, which is: How do I parcel out the requisite information without slowing down the momentum and tension I've initiated and built by starting in the middle?

These three stories address that challenge in three different ways. Price opens in scene. The first thing we get is an action in a particular moment. It's not a highly active action. It's an action of observation: "Strike spotted her: . . ." Because it's located in a particular moment, the tension of the particular moment attaches to it. Anything might happen after Strike spots her. The speaker isn't making a static report: Strike saw this girl one time. The speaker is locating us in a now: Strike spotted her.

Price does some other things here worth our attention. First, our character's name is Strike. This is his street name (he is a dope dealer), and things attach to it. Strike: Speed, power, initiative, efficiency, respect. Ordinarily, we'd hope to get the antecedent before we get the pronoun "her," but Price has a special reason to invert them. The rest of the sentence is an unfolding of everything Strike thinks about this "her" in the moment he sees her: "baby fat, baby face, Shanelle or Shanette, fourteen years old maybe, standing there with that queasy smile, trying to work up the nerve." Is he going to sell to her? Of course, he's going to sell to her. But we sure did learn a lot about Strike as his mental process of deciding whether or not to sell to her is unpacked. By the end of sentence one, he's more complicated than any dozen TV renderings of a young street dealer, and we probably love him. (Note, too – there is so much to like about this sentence! – how Price initiates the fluent street patter that is in some ways the defining achievement of Clockers, and how it lends authority even as it characterizes and brings pleasure.)

Erdrich also opens in scene, but her point of view is highly exteriorized. We're not seeing through the eyes of the would-be assailant, as we see through Strike's eyes in Price's opening. Instead, we're seeing the assailant from the outside, in something like an objective point of view, as a film camera might. This is a useful way for Erdrich to open what turns out to be a mystery story, which will be unpacked through multiple points of view. The first time we see this pivotal scene, we see it from the outside, in a sense reconstructed as a detective might do, and now we'll read on to see how the thing that happened unfolded. Erdrich's kin here is the vaudeville act – (I'll tell you what I'm going to do, then I'll do it, then I'll tell you what I did) – or Charles Dickens – ("It was the best of times, it was the worst of times . . .")

Dark's in-the-middle opening still offers a little bit of expository scene-setting. ("He wanted to talk again, suddenly.") Very soon, we'll learn that the speaker is the mother of a son who is at the very end of a his life. AIDS. And in so many ways, we'll learn, this talk leads to the knowledge that this son, this gay son, is the love of the mother's life. And then, in the story's final scene, we'll get a rather stunning turn, after the son dies, in which the father reveals something about his own unexpected love for his son to the mother through whom we see, and through whose eyes we probably weren't yet ready to see this about the father, but now we are, because of all we've seen. It's as pyrotechnic an ending (in terms of the shock to the heart) as I've ever seen in a story, and it comes at the end of a story whose every part is quietly preparing the reader for it. The quiet opening gains in power and resonance, and we don't know the full impact of "He wanted to talk again, suddenly," until the story's last line.

5. Openings in directly quoted dialogue:

"'Either foreswear fucking others or the affair is over.'" –Sabbath's Theater, Philip Roth

"'49 Wyatt, 01549 Wyatt." – In Parenthesis, David Jones

"'Tell me things I won't mind forgetting,' she said." – "In the Cemetery Where Al Jolson Is Buried," Amy Hempel

It's a big risk to open in directly quoted dialogue, because the reader doesn't yet know who the speaker might be. In the case of Sabbath's Theater, the risk is mitigated by the power of the statement: "Either foreswear fucking others or the affair is over." (Note, too, the two hard f's – "foreswear fucking" – and how they drive the sentence like a hammer drives a nail.) There's another reason, too: The book itself is in many ways a meditation on all that is initiated when the character who says it says it, often from the point of view of the character to whom it was said, and in whose life big upheavals arrived as a consequence. In a manner reminiscent of a strategy favored by Joan Didion, the line will be repeated, inspected, turned over again by the receiver—and what writer could be less like Joan Didion in temperament than Philip Roth? But on grounds of technique, there is plenty of common ground. Matters technical and formal can be appropriated in all directions, toward ends unforeseen by the writer from whom one learns and borrows, and it's unlikely that any but the savviest reader will even see the connection, if the writer of the new thing is stretching out fully into his or her own thing, rather than trying to be the other writer. Our aim is to turn the old means to new ends, and thereby transform the means.

6. A few other kinds of openings:

Contextless fragment whose function will become apparent later:

"Short story about a church on the ocean floor." – From Old Notebooks, Evan Lavender-Smith

"Oh, poor Dad. I'm sorry I made fun of you." "Nietszche," Lydia Davis

Here's some good advice. Whatever advice you've been given, if you push as far as you can in the opposite direction of the good advice, what would otherwise seem the fruit of bad advice can become something that resembles the fruit of really good advice. For more on these matters, I'll send you profitably to Stephen Dixon ("The Apology"), Milan Kundera (The Book of Laughter and Forgetting), Jerzy Kozinski (Steps), Kurt Vonnegut (Slaughterhouse-Five), William Gay ("The Paperhanger"), Ernest Hemingway ("Hills Like White Elephants"), Margaret Atwood ("Happy Endings"), F. Scott Fitzgerald ("Benjamin Button"), David Foster Wallace ("Good Old Neon"), Christopher Coake ("All Through the House"), Bonnie Jo Campbell ("The Solutions to Ben's/Brian's Problem" http://thediagram.com/7_4/campbell.html) and Susan Minot ("Lust").

Establishes alternative donnée (possibly because of altered consciousness, possibly because of space/time/physics displacement):

"In sleep she knew she was in her bed, but not the bed she had lain down in a few hours since, and the room was not the same but it was a room she had known somewhere." – "Pale Horse, Pale Rider," Katherine Anne Porter

"It's one thing to be a small country, but the country of Inner Horner was so small only one Inner Hornerite at a time could fit inside, and the other six Inner Hornerites had to wait their turns to live in their own country while standing very timidly in the surrounding country of Outer Horner." – The Brief and Frightening Reign of Phil, George Saunders

If you've got a special set of ground rules by which the speaker operates and of which the speaker is knowledgeable, best to signal them right away.

Essaying of some sort:

"They are conduits of emotion, kids are." – "AM:31," Amelia Gray

Here and most often, used for comic effect.

Direct Address:

"So, Monsieur, it began with a great gust of wind." – Street of Lost Footsteps,Lyonel Trouillot

Why not?

Yammering by foregrounded omniscient narrator:

"Any mention of pirates of the fair sex runs the immediate risk of awakening painful memories of the neighborhood production of some faded musical comedy, with its chorus line of obvious housewives posing as pirates and hoofing it on a briny deep of unmistakeable cardboard." – "The Widow Ching – Pirate," Jorge Luis Borges

(Get on board or not, the speaker says, but right away you know what you're in for.)

The language of advertising:

"So, you don't believe in a future life. Then do we have the place for you!" – The Quick and the Dead, Joy Williams

Epistolary:

"Since your letter is accompanied by an endorsement from your minister, I am happy to reply." – "A Wilderness Station," Alice Munro

Why not dispense with the narrator conceit altogether, and write your story as a progression of letters (http://www.ninthletter.com/featured_artist/artist/33/index1.html) from people who want things from other people?

Q: What's the takeaway?

A: Don't listen to me. Don't take as gospel anybody's good or bad advice. Take it as a starting point. Test it against everything. Read everything. Learn how to do all the things everybody else can do, so you've got an arsenal ready for any narrative challenge. Be capable. Be smart. Synthesize. Hybridize. Seek contradiction. Embrace contradictory ideas about things. Invent new out of old. Try it again, even if it takes fifty tries, until it makes you feel something. Read a thousand opening sentences. Write a hundred opening sentences if you have to write a hundred opening sentences. Make yourself smarter and more capable than you are now. Learn it so well you can forget it. Then operate out of instinct. Come out punching.

Q: What else?

A: You can do anything if it sings.