David Gessner's Blog, page 91

March 15, 2012

Happy (Pagan) Birthday to Me!

My wife was recently reading Cleopatra: A Life by Stacy Schiff, and found out this about March 15th, my birthday:

My wife was recently reading Cleopatra: A Life by Stacy Schiff, and found out this about March 15th, my birthday:

"Until 44 BC, the Ides of March were best known as a springtime frolic, an occasion for serious drinking. A celebration of the ancient goddess of ends and beginnings, the Ides amounted to a sort of raucous, reeling New Year's. Bands of revelers picnicked into the night along the banks of the Tiber, where they camped in makeshift huts under a full moon. It was a festival often indelibly recalled nine months later."

It all makes sense…..

March 13, 2012

Bad Advice Wednesday: Revel in Creation

Is creativity its own reward? As someone who has written eight unpublished books or so, which amounts to about 16 years of life, this is not an academic question. Rather it's a pressing one.

Is creativity its own reward? As someone who has written eight unpublished books or so, which amounts to about 16 years of life, this is not an academic question. Rather it's a pressing one.

Let's throw out the easy answers. Yes, a couple of these were "apprentice" works that later books built off of. But most were the real thing, from brainstorm to rough draft to many revisions over weeks and months and years. So, since they did not see the light of day, were they "failures"?

In a way, yes. For me writing is a drive for truth but it is also a drive to communicate, and even when that communication takes years of solitary work it is a final goal. This final goal was not realized in these stillborn books, and so yes, on that level they failed.

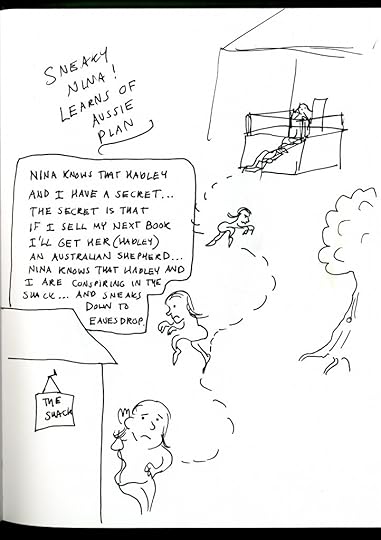

But they did give me something and that something has become the most reliable source of pleasure in my life. Let me give you an example. During the three weeks before Christmas I wrote a children's book for my daughter. It was called "The Adventures of Frisbee Boy and Frisco," and was a sort of post-apocalyptic fairy tale, like a mash up of Harry Potter and the The Road. Frisbee Boy roamed the futuristic wildlands armed only with his plastic discs, and was kept company by his talking dog Frisco.

For three weeks I got up early every day and lived in those wildlands, with their decayed golden arches and crumbling highways and the evil dogmen and water wolves. I wrote and wrote and wrote. It wasn't a perfect creative stretch—there were distractions, there always are. But it was a pretty good one. I wrote for about three hours a day and afterward took walks (see the Bill's last Bad advice–"The Circuit") and even when I wasn't consciously thinking about the book it was still kicking around my mind.

I finished before Christmas and had it bound and gave it to Hadley. I read it to her during our vacation on Cape Cod and she loved it. (I knew my audience and so filled the book with dogs.)

Obviously this book fulfilled the purpose of communication with at least an audience of one. But I'm a professional writer, and couldn't let it go at that. So I sent it to a couple of agents to read. And they were unimpressed. Nope, they said, it's no good. Next I felt my brain do what it does sometimes in the face of rejection; it starts to curl back on itself, fetaling into a ball. The advice I would give my students in this case would be to send it out to a dozen children's book agents, but I don't always follow my own advice. I began to categorize it as safely un-publishable, though it may not be that at all.

But let's say it is, for the point of this discussion. Let's say that's the end of it. What do I "get" out of the book? Well, in this unusual case, I get a gift for my daughter, but, again for the sake of argument, let's ignore that.

What I got, I would argue, were three great weeks. Organized, exciting, goal-driven creative weeks. Weeks that didn't idle and drip. Weeks where the days were marshaled toward an exciting purpose. Whatever the fate of the book, it does nothing to change the joy of creation I felt while working on it.

This is my birthday week, my own personal week of creation, and it turns out that it coincides with a week off from school. As my gift to myself I'm tearing into a new project, a project that may or may not see the light of day in the future. Of course I hope it does see the light of day, that is I hope it serves the higher function of communication. But even if it doesn't I'm not going to stop. As anyone who creates regularly knows, creation provides its own high. And I'm an addict. An addict who doesn't plan on quitting any time soon.

March 12, 2012

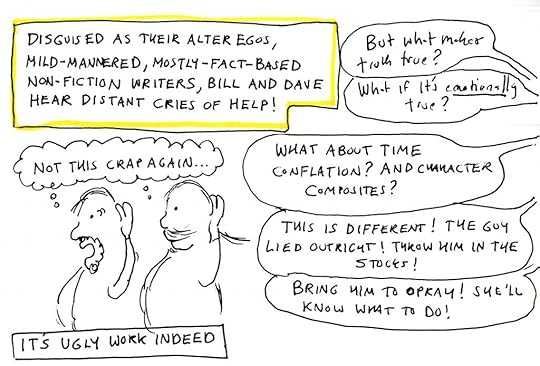

Bill and Dave Enter the D'Agata Storm

For a reasonable (non-hysterical) take on the D'Agata controversy, check out Dinty Moore on Brevity's Nonfiction Blog.

And this one from Ned Stuckey-French…..

March 11, 2012

Dummy Downhill

.

In my ongoing coverage of small town events, I can't forget to offer a glimpse of the annual Dummy Downhill race at Titcomb Hill, the terrific little ski area here in Farmington. It's a community treasure, not three miles from our house. Various endowments fund free downhill lessons, free cross-country lessons, free racing lessons, a kids' race team (F.A.S.T: Farmington Area Ski Team). Little wonder that the Mount Blue High School are state ski champs more often than not, and this year once again. The lodge is a simple barn of a building with volunteer-staffed snack bar. The hill is steep enough for some fun, big enough for a number of trails, and sports a really great system of cross-country trails off the back side. And the view is great. Two t-bars, one pony lift, special after-school prices, and

Death on Skis!

you've got a ski party every day. And Olympic skiers in the making. And boarders. Seth Westcott is from here, for example. I love going up the t-bar with a drippy-nosed kid this trip, a cool teen next, my doctor next, the guy from the stove shop after that, and hellos on the trails. Best of all, kids can ski every day if they want, and they're not on vacation. They're home.

But this is about the Dummy Downhill race. Kids build dummies of all kinds and put them on skis. The dummies are brought to the starting line by kid strength, about a third of a way up the main slope. And one

The winner.

at a time given a shove. There are points for distance, beauty, and most spectacular crash, and of course different builders shoot for different prizes. Some years ago I was there when the Prentiss boys made dummy that included fireworks. The fireworks set the foam insulation they'd used as part of the structure ablaze, and by the time the dummy got to the finish line it was a ball of orange flame running a tail of black smoke. They'd built well, and having just missed the t-bar house

The scene, with jump visible

the dummy kept going, clear across the Nordic basin and under a small balsam fir tree, which burst into flame, too. First prize!

And now a strict no-flame rule.

This year's entrants including Death on Skis, Devil Princess, a tinfoil dog, Half Man (just legs and waist-pretty

Princess Devil about the hit Foil Doggie

eerie), Mini Titcomb Lodge, a huge baseball, a large-scale fighter jet, and a number of human forms. I like the human forms best because they make these wonderful inadvertent gestures when they ski and then when they crash. And

Mini Titcomb Lodge, retreating, rocking horse and stuffed bear, foreground.

they just keep smiling. Except for death, whose head popped off to cheers.

After the first run, you put your dummy back together as best you can, drag it back up the hill, and send it over the jump! This is nothing short of awesome.

This year's winner was the jet, which was wired for radio control, ailerons, jet noises, exhaust sparks and all, such that mid-jump it was able to leave its ski-base and fly thirty or forty feet before crashing and breaking its nose.

Meng Hardy with Death's all-too-real scythe

Half man, foreground. Is that Bert or Ernie back there?

March 10, 2012

Getting Outside Saturday: Ice Out

2012: Very Early, Very Gentle

.

Ice out on the Temple might come slowly, weeks of warming temperatures, stream slowly emerging, easily swallowing all the melt, or it might come all at once—a day's work after hard rain. It's an equinoctial event, coming generally within a week either way of the equinox. After an all-night downpour, the ice we've admired all winter, the ice we've come to regard as permanent, starts to float. Guessing it's imminent, one rushes down there in the morning, early. At the bend in the path, one sees that the Dairyman's lowest field is full of water. More rain than one thought? So to the bluff and lookout, where one sees it: a muddy river flowing over the ice. And though this kind of overflow may have happened in a thaw back in February, this time it's different, this time the ice is lifting on the voluminous flow, folding and breaking in huge slow movements, damming the stream just enough to flood the low parts of the field.

One has appointments, one has work to do, but one stays. After an hour of suspense—grinding, subtle movements in the ice—there's a roar upstream as from a volcano, and a clapping sound, the slamming of enormous dominoes, and suddenly around the bend a prodigious wave arrives: an ice dam has broken somewhere upstream. This new water lifts the ice three feet in a single heave, breaks it in huge pans that want to move downstream, too, lifts them on top of the downstream ice, lifts whole sections twenty feet square, eighteen inches and two feet thick, lifts them and tilts them and breaks them further. The upstream ice keeps coming—large floes and pans bumping and thumping till they meet the blockade, where they tilt and flip and add themselves to its mass. Wherever the water still flows freely, the floes slip under, disappear. More arrive, more tilt and stop or sink and disappear, more and more till the void is well filled, the streambed dammed bank to bank five feet high. The water rises fast, pours over the ice dam, thrusting new pans on top and adding whole trees, last year's sweepers, which will sweep no more. The pans stack up. The water rushes higher, raises the dam, till abruptly the last piece comes into place, an enormous pan that flips and breaks against all that's already in place just below one's vantage point, blocks the stream utterly to a height of ten feet or more. Then all is quiet as the stream mounts, even as more and more ice arrives from the morning's upstream break-outs. The stream rises fast—a foot in a minute, five feet in five minutes, huge pressure building behind the ice. One backs away from the edge of the stream—even on our high bluff, the ice is getting close, all seems ready to explode.

Then, sudden stasis as the stream goes out of its banks and flows into the lowest field, making room for all the new water and ice. Ice pans like loose swim rafts drift placidly out where the cows used to stand, pushing over the forgiving streamside alders till there are no alders in sight, bashing the bark off hardwoods (accounting for all those scars one sees in summer: a barkless patch twelve feet up a streamside maple, a branch no moose or man could reach or hope to break mysteriously torn away above that placid, innocent brook).

The water rises, rises more, flips more pans in front of the dam it has built, rises more, rises to the height of the bluff across the stream, the dam rippling under all the pressure, then bucking, about to let go, enormous flats of ice pushing up the high bank at one's feet. The stream has filled the lower field; the lower field is now stream. It's flowing. And it is rising. Quickly, the flood crests the other, taller bank and the height of water finds a new course, cuts the stream corner, eats the snowpack rapidly, carries ice chunks well into the Dairyman's higher field. Quickly again, this new streamway is blocked. The water crests our bluff—one jumps up on the talk rock, spellbound, ready to run. Now the stream mounts more slowly, filling a huge basin, something on the order of five minutes to a foot. It's been an hour and a half from the start of the show.

In the ice dam there's a heaving, then a pressure bulge from below. Upstream, a large new pan of ice gets stuck, flips in the current, makes its own dam, one that briefly impounds the stream behind it, but abruptly it breaks, explodes really, unleashing a wave that hits the bigger dam all at once, raising whole sections of it. Then, unimaginably, the front wall of the assemblage rises at once, flipping backwards onto the whole with a roar like close thunder, and the new front edge bursts, too, all the millions of pounds of backed-up water roaring though ice in a new channel that grows and grows, throwing floes, flipping pans up on the banks, creating short-lived sub-dams that deposit tree trunks and ice walls high on our bluff, up into the very branches of our trees, extraordinary violence, the material of the original dam slowly flushing down over the local beaver dam (the proximate cause of the bottleneck), then taking that, too, sticks and logs and rocks and ice floes and bigger pans and muddy water roaring into the pool downstream, the solid old ice of which simply folds up, no match for the onslaught, folds up and forms a slow, roaring accordion pleat in front of an eight-foot high wall of debris that pushes downstream and within seven minutes rounds the bend a couple of hundred yards away. There's no dam anymore, none. The accumulated water, freed, flushes out of the higher field taking most of the snow cover with it, then flushes out of the lower field, leaving huge ice pans high and dripping. Within half an hour the stream is back to gently flowing in its bed as if the season were autumn again, muddy but mild, utterly free of floating ice, its banks strewn as far as one can see, the alders crushed and buried, the sweepers gone, the hard-won beaver dam absent, sticks and old leaves and mud and dripping blocks of ice everywhere, enormous marooned pans settling, breaking on each other, the whole looking (as Juliet once observed) like the remains of a house after a catastrophic fire, winter washed away in under two hours time.

.

From Temple Stream (Dial Press)

"A Marvel in a genre that's tough to master." –National Geographic Explorer

March 9, 2012

Edith Pearlman Wins! (And so do small presses!)

Congratulations to Edith Pearlman on the National Book Critics Circle Award in fiction. And to Lookout Books. It's just amazing that this could happen to a tiny press with their very first book. Credit Emily Smith and Ben George, who worked tirelessly (and brilliantly) to make their dream a reality. Talk about an underdog winning….

Emily Smith, Edith Pearlman, and Ben George celebrate!

Binocular Vision, Pearlman's story collection, was praised for its "lapidary language" and its "moments of grace." She thanked the NBCC for awarding the short story, a form often overlooked. She praised her publisher, Lookout Books, "who chose me for their debut author." Said Pearlman, "Little presses and little magazines are dedicated to keeping literature

alive, and they deserve thanks from every writer; tonight, particularly from me."

Check it out:

http://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/book-news/awards-and-prizes/article/50985-national-book-critics-circle-awards-go-to-pearlman-jasanoff-gaddis.html

March 8, 2012

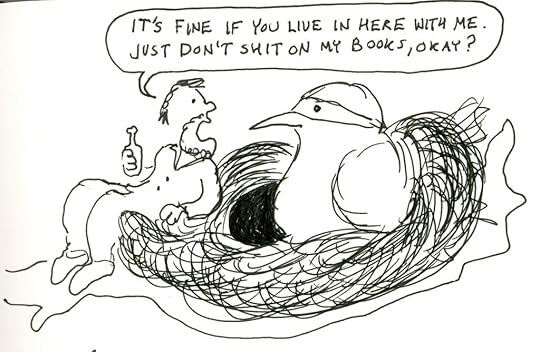

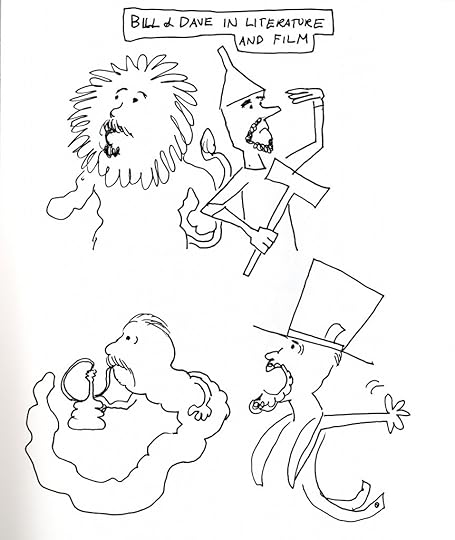

Dave's Random Doodle Day

March 6, 2012

Bad Advice Wednesday: Take a Circuit

An Early Circuit

Part of the writing day for me is a circuit. This has been true no matter where I've lived, and I've lived a lot of places since I started writing seriously. The country circuit is the one I'm on now–every morning out on skis at this time of year, or walking in the summer, or maybe riding a bike, sometimes swimming. The idea is a similar or the same route each day, preferably a loop (no backtracking), one that takes me through my thoughts as surely as through the woods or through the streets of whatever given city. The first twenty minutes are often a tumult of spare thoughts–stuff that a desk only encourages–and then, well, wow, I look up and see the trees, or the buildings, or the surf. The twenty, I know, corresponds to how long it takes for endorphins to get to the mind during exercise. But never mind the science: suddenly, ineluctably, I am there. Or rather, here. Here where I am, and not there where I'm not. And once I arrive, I begin to write. Not with a pencil, and not with a pen, and not with an old Selectric, certainly not with this laptop, but up there in the leaves, and over in that plaza, and down in that very clear water.

When I lived in Soho, in New York City, my loop was straight up LaGuardia and into the village, then all the way up Bleecker Street to West 4th and to 11th (yes, weirdly, West 4th crosses West 11th), then out to the river along 14th Street, then by many routes homeward. When I lived in the Meat District (Meat-Ho, we called it), I reversed the course, heading down Bleecker and all the way to Lafayette, then downtown into China, and around. In Columbus it was German Village, or on a bike clear to campus along the rivers. In Worcester, it was through the woods around the Holy Cross campus, on foot, on skis, through construction zones, didn't matter. Here in Maine it's through the woods along the stream on this loop or that, the busy world of birds and bugs and fish and frogs.

(Can't sleep? Need to relax? Take your circuit in your mind even as you lie in the dark. Picture every step, every sight, all the sounds. This works. Zzzzzzz.)

The point is to walk an hour or two in privacy, nothing but your thoughts, and end at the desk. Full of those endorphins and having thought the circles away and found the straight lines, I'm able to leap right to it. Often, I've held whole paragraphs in my head, wanting only the computer to take dictation from my fingers. Equally, I take notes in one of my little books. These I either transcribe or ignore: it's all equal in the end.

The walk is where I solve the problems. The walk is where I leave the demons. The walk leads me to my studio, and that it took an hour to get there makes it all the more imperative I write.

On trips I find a circuit wherever I am. In Billings, Montana, I walked the Yellowstone River across from an LPG plant. I did it every day I was there. In Rome I found the Pantheon by a thousand routes–but the Pantheon was the goal going out, my desk (at a flyblown former palazzo of a hotel) the goal coming back.

So, invent a circuit. Make it kind of long. End at your desk. Write what you've walked up. Or sing it. Or dance it. Anyway, do what you do after the circuit prepares the way.

And let the walks get longer.

(For Kate Neptune Baum)

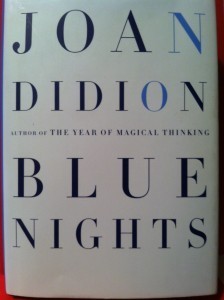

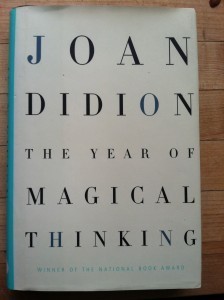

Reading Under the Influence: Joan Didion

No

A critic on a radio show not long ago asked how Joan Didion could write about the death of her husband, the death of her daughter, two books, implying something that went unsaid, maybe that Ms. Didion was exploiting her tragedies. But, Radio Guy, she's a writer. That's who she is. She writes about her life. Was she supposed to not write about this? Her husband, the writer John Gregory Dunne, died suddenly at their dinner table. Not long after, their adoptive daughter, Quintana, died as well, a little more slowly. Strangely, Didion doesn't mention Quintana's death in the first book. But I agree: that's a different story. In these books, The Year of Magical Thinking and Blue Nights, Didion explores what we go through in the face of such loss. I say we, because while she is recounting her own experience (and very bluntly) she is speaking universally. She does this by never using a single bromide. Nothing like "Everything happens for a reason," or "Whatever doesn't kill you makes you stronger." Didion tells us the truth. Things happen for no reason. Things that don't kill you

JOHN

often leave you devastated permanently.

I heard her say once (I believe on Charlie Rose, I believe about The Year of Magical Thinking): "I wouldn't say it was about death, it's about whether you'll survive."

Magical thinking refers to the not letting go of someone who is dead, not truly admitting he or she is dead. It's denial. It's a little theatrical, keeping a player onstage. For example a friend called once to tell me that her sister had died in a car crash, and gave the details. And later in the call she asked if I wanted to go visit her sister soon, because of course the sister could use the support. Maybe we'd just go

together and see her. I asked where and the answer was silence. I said, "But you said she has passed away." "Yes. But let's go see her. I think she's in San Francisco." Perfectly serious, perfectly logical. Even in the knowledge that the sister was dead. That was magical thinking.

The phrase "blue nights" refers to a certain time of evening at a certain time of year, a family phrase

at Didion's house, here called up to evoke more magic, but a more atmospherical magic. The book broke my heart. And its message, to the extent is has one, is this: There really isn't any comfort.

A student pointed out that the blue highlighting on the cover of A Year of Magical Thinking spells out J-O-H-N. On Blue Nights, it spells out N-O.

March 5, 2012

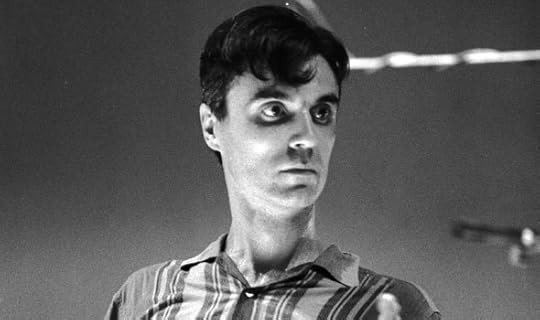

David Byrne Meets Ned Ryerson

We are fans of quirky here at Bill and Dave's. (We even like to think we are a tad quirky ourselves.) And lately I've come upon a couple examples of this here inter-web at its quirky best. For instance, my friend Betsy sent along this great lecture/animated film on education. For another, there's the pleasure of having Groundhog Day's Ned Ryerson come back into my life. You remember Ned (if you don't, or even if you do, here's a Youtube video with all his scenes from the movie.) Anway, I hadn't thought about him in years until a student of mine, Carson Vaughn, sent me this note:

We are fans of quirky here at Bill and Dave's. (We even like to think we are a tad quirky ourselves.) And lately I've come upon a couple examples of this here inter-web at its quirky best. For instance, my friend Betsy sent along this great lecture/animated film on education. For another, there's the pleasure of having Groundhog Day's Ned Ryerson come back into my life. You remember Ned (if you don't, or even if you do, here's a Youtube video with all his scenes from the movie.) Anway, I hadn't thought about him in years until a student of mine, Carson Vaughn, sent me this note:

"I meant to send this after the first day of class, but bit-part character actor Stephen Tobolowsky (think Ned Ryerson on "Groundhog's Day") has a fabulous podcast called "The Tobolowsky Files" available for free on iTunes. Episode 12, "The Voice From Another Room," is about his relationship with David Byrne and his work on the film "True Stories." You mentioned being a big Talking Heads fan, so I thought I'd shoot you the link:

"I meant to send this after the first day of class, but bit-part character actor Stephen Tobolowsky (think Ned Ryerson on "Groundhog's Day") has a fabulous podcast called "The Tobolowsky Files" available for free on iTunes. Episode 12, "The Voice From Another Room," is about his relationship with David Byrne and his work on the film "True Stories." You mentioned being a big Talking Heads fan, so I thought I'd shoot you the link:

http://itunes.apple.com/us/podcast/the-tobolowsky-files/id339001481?ign-mpt=uo%3D4 (Episode 12)

Tobolowsky is also just a really great story teller. I recommend almost all of them."

And it's true. The guy is great. Bing! Check out episode 12.