David Gessner's Blog, page 90

March 28, 2012

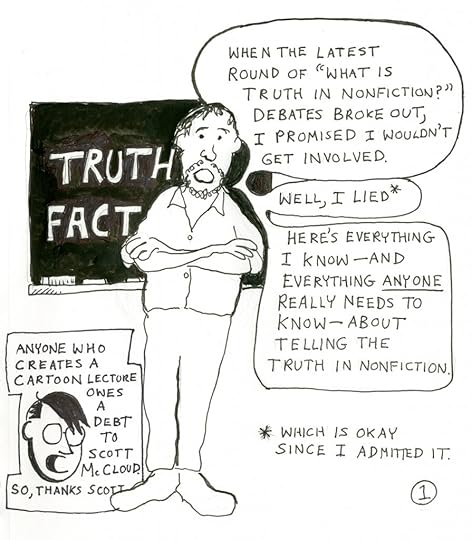

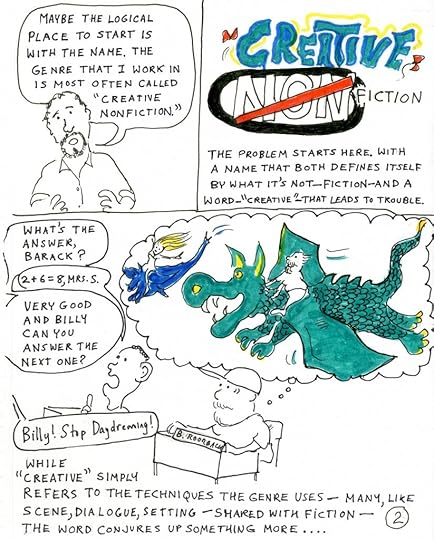

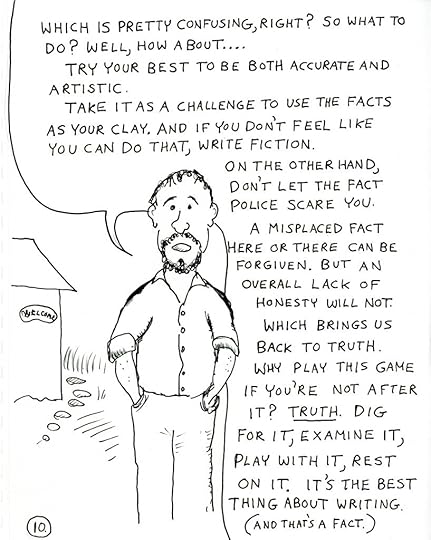

Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About Truth in Nonfiction But Were Afraid to Ask: A Bad Advice Cartoon Essay

March 27, 2012

Has Spring Sprung Early?

This morning the newborn Carolina wrens are busy begging for food. A hundred feet in front of me a mute swan has built a much larger nest. Meanwhile last week I heard (but did not see) a painted bunting, a bird aflame with color that has come back from points south far too early.

This morning the newborn Carolina wrens are busy begging for food. A hundred feet in front of me a mute swan has built a much larger nest. Meanwhile last week I heard (but did not see) a painted bunting, a bird aflame with color that has come back from points south far too early.

"Phenology," writes Jack Turner, "is the study of the mature naturalist." And what is phenology? The discipline of watching phenomena change as the seasons turn. I remember my personal highlight as a phenologist. It was fall and we were living on the beach on Cape Cod, and after a walk I said to my wife, "The seals should be back soon." Each summer "our" seals migrated to the cooler waters of the Gulf of Maine, and each fall they migrated back.

The next day, walking again, I saw that the seals were indeed back, loafing on the offshore rocks. I couldn't have been more thrilled by a promotion at work — and in a way, that's just what it was.

Phenology has always been a private science, a way of getting your own clock in synch with the world's, and so far there have not been any Nobel Prizes awarded for knowing when the seals will be back. But that may be changing. It has been reported that the notes made in the journal of the granddaddy of phenology, Henry David Thoreau, are finding a whole new relevance.

It turns out that the meticulous phenological notes that Henry made in his journal are now being used to confirm what anyone who has lived through this non-winter already knows: spring is springing much too early. Recently, Richard Primack, a professor of biology at Boston University, and Abe Miller-Rushing, who was his grad student at the time, took notes on the same species that Thoreau had observed beginning in 1851 and concluded that nature's timing has changed for the earlier.

How wonderful that Henry's private notes should play this public role. I think of one of his own favorite metaphors, one he employs on the last page of Walden, that of the "strong and beautiful bug," which emerged after lying dormant inside of a farmer's wooden table for sixty years, after having been deposited in the living tree "many years earlier still." Thoreau concludes: "Who does not feel his faith in a resurrection and immortality strengthened by hearing of this?"

What thrills him is that something — insect or idea — can sleep for decades before springing back into "beautiful and winged life." And now his journals are doing the same thing, speaking to us a hundred and fifty years after he spoke to them. It's true the news they tell is bad, but I can't help but find the fact that they can speak to us at all is hopeful.

Who would have guessed? Noticing, it turns out, can be valuable.

March 26, 2012

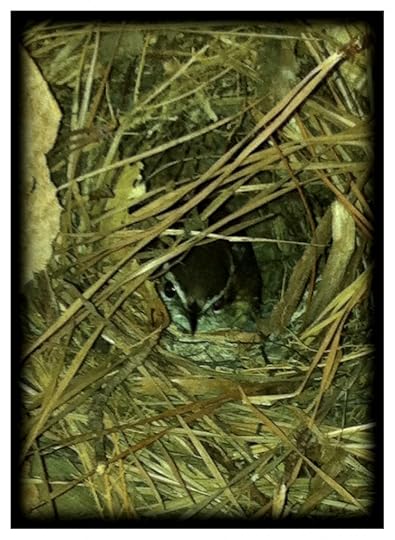

Wren Cam: Day 2

You asked for it and we gave it to you…..live from the shack. A Bill and Dave production. Day 2 in the life of the Carolina Wrens….

You asked for it and we gave it to you…..live from the shack. A Bill and Dave production. Day 2 in the life of the Carolina Wrens….

Click here: 003

Nature Photographer: Nina de Gramont.

March 24, 2012

Getting Outside Saturday: "Scioto Blues"

The Scioto and Downtown Columbus

[This essay is from my book Into Woods and originally appeared in The Missouri Review. Later, Harper's picked up an excerpt for their "Readings" section. It was written in about 1998, and since then I've developed a much fonder feeling for Columbus.]

.

.

Scioto Blues

.

If you move to Columbus, Ohio, from Farmington, Maine, you will not be impressed by the landscape. It's flat around Columbus and the pre-prairie rivers move sluggish and brown. In Maine you pick out the height of flood on, say, the Sandy River, by the damage to tree trunks and the spookily exact plane made by ice and roaring current tearing off the lowest branches of riverside trees. In Columbus you pick out the height of flood on the Olentangy or Scioto rivers by the consistent plane attained by ten thousand pieces of garbage, mostly plastic bags, caught in tree branches.

Always in the months after I moved I was looking for a place to run the dogs, Wally and Desmond, who are Maine country dogs used to the unlimited woods. We started on a subsidiary athletic field at Ohio State—long, kick-out-the-jams gallops across mowed acres, lots of barking and rumbling—then leashes to cross Olentangy Boulevard and a parking lot, so to the Olentangy River (my students call it the Old and Tangy), where the boys swam hard just across from the Ohio Stadium, known as The Shoe, in which the football Buckeyes famously play.

By the time the University started building the gargantuan new basketball arena in the middle of our running field, the dogs and I had found Whetstone Park, a big urban preserve a couple of miles upstream, just across the river from Route 315, which at that point is six-lane, limited-access highway. Really, Whetstone's a lovely place, well kept, used in multiple ways, though not much in winter, always the sounds of 315 in the air like a mystical waterfall with diesel power and gear changes. There are athletic fields, a goldfish pond, picnic areas, tennis courts, basketball courts, an enormous and important rose collection in a special area called Park of the Roses, just one section (about three miles) of an all-city bike path, tetherball, speed bumps, a library branch (in satisfying possession of my books), fishing spots on the Olentangy River.

Which runs through Whetstone after a scary trip through a couple of suburban towns (Route 315 its constant companion), through a dozen new developments and several parks, past or near at least six shopping malls, also through the backyards of people who love the river, love it to death. Indeed, the detritus at its banks in Whetstone is emphatically suburban. Plastic grocery and other store bags of course dominate, festooning the trees in various colors, the worst of which is the sort of pinky brown that some stores use in a pathetic and surely cynical attempt to imitate the good old kraft paper of the now fading question, "Paper or plastic?" The best colors are red and blue, because at least there's that moment of thinking you see a rare bird. Garbage bags are part of the mix, too, but heavier, so lower in the trees.

Certainly plastic soft-drink bottles come next in sheer numbers. These things float best when someone upriver has put the cap back on before flinging, perhaps out of a car window. Or perhaps not flung, but only left beside a car in a parking lot along with a neat pile of cigarette butts from the emptied car ashtray. Come to think of it, these bottles are probably seldom thrown directly into the river. The plastic walls are thin, so plastic bottles aren't always the long-distance travelers you'd think. Cracks let water in, and silt. The bottles don't end up often in trees, either, because they are light enough and smooth enough for the wind to knock them free. They are everywhere, though. They rule.

Tires occupy their own category, and come in two sorts: with and without wheels. Those with wheels are heavy but float, so end up high on logjams and in trees; those without wheels get caught up in the silt and mud and form strange ring-shaped silt islands or, buried deeper, show just a little tread as part of a sand bar, or deeper yet, disappear from the world of light and air entirely, perhaps to emerge in a century or two, a millenium, or more. They aren't going anyplace.

Next there are car parts other than tires. Like bumpers and doors and hoods. These must be dumped at river banks, is my guess, off the edges of parking lots built too close to the water, then carried by floods. Occasionally, too, a whole car gets in the water, and slowly demonstrates the second law of thermodynamics: all things seek randomness. Entropy continues its work of unworking, and the car spreads downstream. The iron involved is at least no problem.

Aerosol containers make a strong showing in the river, those former dispensers of paint and freon and deodorant and foot spray and whipped cream and so forth. Indestructibly happy bobbers, these canisters are capable of long trips, clear to the Gulf of Mexico, I'm sure, and before long into the oxygen-free, Lake-Erie-sized dead zone the Gulf now boasts. But some do get up high in tree crotches and last there for years—decades if they're of stainless steel. WD-40 as a product gets a special mention here, for the paint on the outside and the oil film on the inside keep these cans alive and recognizable for years wherever they roam.

Newspaper and other print matter turns up but disappears just as fast, leaching what it leaches into the water. A special category of printed matter I ought to mention is pornography, which I often find high and dry, the park being its entry point into the river. Juggs was one magazine I happened across. It had many photos in it of women who'd had obviously harrowing operations. Also, some kind of trading cards that featured various young women naked. These I discovered clipped neatly by the bark flaps of a shaggy hickory at the eye level of a large adolescent or small man, footprints and dribbles beneath, the whole gallery abandoned after our riparian onanist had done his work.

Other items: prescription medicine bottles, but not in abundance; mattresses common, usually appearing as skeleton only, that is, the springs; pens of endless varieties, mostly ballpoint, ubiquitous, some working; twisted shopping carts; tampon tubes of pink plastic made by, I believe, Playtex (plenty of these, from flushes, giving lie to the idea that sewage is well managed upstream); guard rails; lengths of rope of various types; lengths of cable, mostly Romex; joint-compound buckets (but these are fast fillers and sinkers and join the silt banks permanently with their tire friends and with broken glass bottles).

Glass. Any glass that turns up (except tempered, as in windshields) at least turns back to sand, squandering its legacy of power and fire. The rare complete glass bottle with lid does float by, but these are goners, baby; first rock they encounter and it's smash, step one toward beach glass for kids to find. Eyeglasses you'd think would be rare, but just in the last year I've found three pair, lenses intact.

Planks. Now, planks hardly count, being trees, but often planks have nails, which hardly count, either, come to think of it, being iron. Then again, planks are often painted, so they do add to the color stream—what's that purple? What's that turquoise? A bright yellow board I saw once caught up in a willow was particularly startling.

Now, pieces of Styrofoam are important in this trash system. There are blue pieces often enough, occasionally green, but white is most common. Everywhere are the tiny cells that make up the product—billions of bright spheres, with samples worked into every handful of mud. Packing popcorn, too, everywhere. Cups, sure, but these don't last long. Coolers predominate. Then chunks, which must come from packing materials. Then even bigger chunks, unexplained on the Olentangy, and nowhere as big as the huge chunks found on beaches on the seacoast in Maine, parts of boats or floats or who knows what. And oh, yes, speaking of beach flotsam, boat parts are common too, even on rivers, and even in the Olentangy. Fiberglass boards, not too big, or rowboat seats, or canoe prows, rarely. This is not a sport river.

Though there are fisherman, and there are fish. Catfish and smallmouth bass, most notably. And the fisherman leave their own class of trash: broken fishing rods; lots of line tangled in branches above; bobbers hanging from power lines; lead weights. Lead is poisonous, of course, so a special mention. Also lures sometimes, hanging as well. Or just plain hooks in a branch, dried up worms. Little boys, mostly, though lots of retired men like to fish the river. Also men who don't look old enough to retire, maybe some of those guys who have I'D RATHER BE FISHING bumper stickers on their bumpers (and their bumpers still attached to their cars).

The fisherfolk also leave packaging for hooks and snells and bait and so forth. American Eagle is one of the brand names you see frequently in the mud. And plastic bait cups are just everywhere, their lids not far behind, these packed by local concerns, sometimes with an address printed along with the logo so that I can mail the shit back to them (yes, I'm a crank). They may not be responsible for their customers, but they should care where their names turn up.

Some of the other garbage comes with brand names, too: Budweiser, Wendy's, Kmart, Big Bear, Dow Chemical, General Electric, Goodyear, to name just a few. All these big names sticking up out of the mud! It's like some apocalyptic ad campaign!

Now for the less tangible. Apart from the major chunks in the Old and Tangy River, there is the smell, and the smell must come from somewhere. It's not horrible or anything, not even pervasive, but when the dogs get out of the river there's not only the usual river smell—mud and oxygen and hydrogen and fish and pungent organic rot—there's something else, one notch below healthy on the dial. My amateur analysis is as follows: equal parts motor oils, fertilizers, and straight human shit. Also shampoo and detergent, the faintest sickening edge of perfume.

Which leads me to the foam, good bubbly stuff that can stack up to two or three feet high and is sometimes wishfully called fish foam. But fish foam hasn't the density of suds, not at all, and smells like fish rather than perfume.

I mean, the river is a junkfest.

That's the Olentangy before it gets to campus, and before it passes the mysterious outflow pipes of a certain national research firm[1], and arrives in the large skyscraper downtown of Columbus. And Columbus is big—bigger than you think, an Emerald City that pops up on the Central Ohio flats. It's said to be the biggest city in Ohio, population about 1.25 million inside the Greater Columbus loop of I-270. The city's official slogan should be it's not that bad, since that's what people tell you, over and over. I think the actual civic slogan is more than you dreamed. True. And that huge, worthy school where I was comfortably tenured: 60,000 students, 15,000 staff, 5000 faculty. Something like that. A city within the city. The Olentangy flows right through campus, unassaulted except by lawn chemicals and parking lot runoff and frequent beer vomit on its way to the Scioto.

Columbus' two main rivers meet at Confluence Park. This is not really a park at all, but some kind of convention or catering facility on city land, probably the result of all kinds of inside deals. I took the dogs there once in my early search for dog-walking paradises. Confluence Park was hard to find. There are so many roads crisscrossing each other and exit ramps and overpasses that you pass the place ten times before you get to it, a scavenger hunt of signage, and then when you finally get there it's just another parking lot next to the river. Oh, and the catering facility and their big dumpsters overflowing with whatever party has just come through, making someone a nice private profit on public land, is my guess. And meanwhile, plentiful homeless have pulled all the liquor bottles out of the dumpsters for years, getting those last drops then creating a midden of broken glass down along the water[2]. No park at all, just a steep, rocky, trash-strewn embankment forming a point of land where our two protagonist rivers mightily meet, the greater silt carry of the Olentangy coloring the greater water volume of the Scioto somewhat. Here the Olentangy gives up its name, and the two are one: Scioto.

Which marriage flows through the big city under several bridges, looking like the Seine in Paris (the Seine a dead river, by the way, fishless, oxygenless, killed, unlike the Scioto). But the Scioto is not a navigable river like the Seine; the Scioto's only four feet deep and heavily ensilted. I won't say much about the appealing replica of the Santa Maria that floats here trapped in a specially dredged corner under the Broad Street bridge in a 500th-year anniversary testament to a man who never reached the Midwest but gave his name to our fair city nevertheless.

Anyway, just below town, the river pillows over a containment dam a couple of hundred yards wide, a very pretty fall, really, the funny river smell coming up, men fishing, bums and bummettes and bumminas lounging, bike path twisting alongside, highway bridges, rail bridges, two turtles on a warm rock in spring, egrets, herons, seagulls, swans, busterns, kingfishers, beavers, muskrats, rats.

And no dearth of trees to catch the trash after flood! Maple, ash, cherry, gum, walnut, oak, locust, sycamore—on and on, dominated thoroughly by cottonwoods, which in the spring leave a blanket of cottony seed parachutes in a layer like snow.

The parks once you pass below the city are more than a little tawdry—poorly cared for, placed near the police impoundment lot and the railroad yards and light industry and a complicated series of unused cement ponds that once surely were meant as a sewage treatment facility. Oh, also in sight is the practice tower for the fire department, which trainers douse with kerosene and burn for the recruits to put out. Miles and miles of chain-link fence, altogether.

On the northeast bank of the river is Blowjob Park, one of my students called it in an aside in a paper, which I found because it is at the very end of the bike path. The path ends at a parking lot, where lonely and harmless-looking men sit in cars gazing at each other and waiting for liaisons. The city sometimes arrests these men in courage-less raids, not a homophobic act, says a spokesperson, for the men are said not to be gay exactly, but married guys looking for action of any kind, loitering and littering and certainly dangerous so close to the impound lot and the defunct sewage-treatment plant.

When I moved downtown, downriver, to German Village (a turn-of-the-20th-century neighborhood—now trendy—of brick buildings and restaurants and shops, surrounded by what some Columbusites have called slums in warning me, but which are just further neighborhoods, with less and less money apparent, true, but plenty of lively children and sweet gardens and flashes of beauty in along with the ugliness which isn't much worse than the general ugliness that pervades this end-of-the-eastern-woodlands city and its suburbs) . . . when I moved downtown, I brought the dogs over there for a walk and a swim, two of their favorite activities. Down below the dam, I nodded to men fishing, and the dogs raced happily, and it wasn't bad. You go down below the dam and the riverbank is broad and walkable in dry times—this first walk was in autumn—and you see good trees, remnants of the hardwood forest, and chunks of concrete under the Greenlawn Avenue bridge and re-bar wire and yes, examples of all the junk listed above, particularly those plastic grocery bags in the trees, but fifty-five-gallon drums as well, and broke-down lawn chairs used for comfort by fishermen and abandoned when beyond hope. Also some real dumping—an exploded couch, perhaps thrown off the high bridge, and some kind of switchboard with wires dangling, and a filing cabinet with drawers labeled Contracts, Abstracts, Accounts Payable, and Personnel. It would not take much, I thought at the time, to figure out what local business all this came from. Might be fun to return it, but a lot of work. And probably they paid some asshole to cart the stuff to the dump, some asshole who kept the dump fee and emptied his truck off the Greenlawn Avenue bridge.

And down there, too, was a large concrete bastion of a culvert, labeled with a sign: Caution, Combined Sewer Overflow. In other words, when it rains, get out the way. And if you think "Combined Sewer Overflow" just means rainwater washed off parking lots, listen: in the rich, dried mud right exactly there, the dogs and I hiked through a thousand, no, ten thousand, plants I recognized (and you would recognize, too, at once) as tomato vines. How did so many tomato plants get sown? Well, tomato seeds don't readily digest, generally pass through the human digestive tract unscathed. You get the picture.

And the doggies and I walked that sweet fall day. After the bridge it's hard going, a rocky bank strewn with valueless trash, but also bedding and clothes, particularly male underwear for some reason. It's not too pleasant, and getting steep, so I turn back, but not before noting that across the river there is much park-like land, sandy soils under great canopy trees. Dog paradise. How to get there?

Wally and Desmond and I hike back to the car, drive clear around to the Greenlawn Avenue bridge (it looks very different from above), and find the entrance to what is called Berliner Park. I'm excited. There are baseball fields and a basketball dome and a paved bike path along the river (a discontinuous section, as it turns out, of the Olentangy bicycle trail that also passes through the Whetstone Park mentioned above), and many footpaths to the water.

In the woods along the river there is the familiar trash, of course, multiplied enormously by the location just below the city and just below the dam. Here's how it gets there: rain falls, perhaps during one of the many thunderstorms Columbus enjoys. The parking lots puddle, then begin to flow, carrying gasoline and oil and antifreeze of course, but also cigarette butts and cigarette packs and chaw containers and pop bottles and aerosol cans and many tires, just simply whatever is there. The light stuff gets to the river fast. Tires move a few feet per rainstorm, but they make their ways, oh, make their ways to the river or get stuck trying. Shopping carts probably have to be actually thrown in, but shopping bags get there two ways—flow and blow. Kids' toys are carried downstream just like anything else. And what can't float waits for a flood. Anything can ride a flood! Anything at all!

It's a mess. In fact, the part of Berliner Park that lies along the river is so bad that most people just won't hang out there. That leaves it open to what I call lurkers, men who lurk in the trees and know that my two dogs mean I'm a dog walker and not a lurker, and so not to approach. My dogs have even learned to ignore them, and I have, too. Each to his own.

Except for the one lunkhead who threw a rock in the path in front of my wife, but he seemed just developmentally delayed, no malice, and with the dogs along gentle Juliet felt safe enough, but hurried up out of his purview.

And except for the dead body I saw police divers pull out of a snag one day. Female, probably the suicide that had been reported two months earlier, although that jumper from the Greenlawn bridge had been identified as male by witnesses who tried to stop him jumping. The dogs rushed to have a look, came back quick. I talked to the cops a little. 'Nother day, 'nother dollar kind of talk.

And once I found a note—poignant and plaintive, a personal ad aimed directly at its market, pinned to a log: "Loking for love. Grate Sex. Call me up or meat heer, meet hear." Also this, written in Magic Marker on a bare-flayed log: suck you good. With a shaky arrow pointing to an uninviting side path.

During one of our weekly phone talks, I told my mother about Berliner and all the trash. She said, Well, why don't you and a couple of your friends get together and go in there and clean it up?

She's right, of course. It's easy to complain and not do anything. But, Jesus, the flow of garbage is so great that my friends and I would need to work full time till retirement to keep up just with the one park. Perhaps the city could hire a River Keeper. I do pick up this bottle and that can, and fill a bag now and again. It's the least I can do. Yes, the least. Okay, I'm implicated here, too.

Downstream a little further there's another storm sewer runoff warning, and the vile smell of unadulterated, un-composted shit3. The bike path goes on. It's not a bad walk once you are past the stench, which takes a minute, because there is also a honey-truck dump station right there, which you can see from the path, a kind of long pit where the septic-tank-pumping trucks unload. This stuff has a more composted reek, a little less septic, so there's no danger of puking or anything. The dogs run on, free of their leashes, because there just isn't ever anybody around here, except lurkers. The dogs have no interest whatsoever in lurkers, and they love nothing more than a good stink. The path ends at a six-lane highway spur-and-exit complex, but not before passing a stump dump and a wrecking yard, ten thousand crashed cars or so in piles. Also a funny kind of graveyard for things of the city: highway signs, streetlight poles, unused swimming rafts, traffic cones4. Under the highway bridge isn't too inviting, frightening in fact, but if you keep going there's a fire ring and much soggy bedding, a bum stop, and above you, up the bank and past a fence or two, the real city dump.

Here we (dogs, Juliet, myself) most commonly turn around and head back. And I guess I'd be hard-pressed to convince you or anyone that it's not that bad walking here. Really: it's not that bad. The dogs love it. But they do get burrs, and Wally, the big dope, insists on diving into the reeking storm sewer runoff, so we have to make him swim extra when we get upstream, where the water's cleaner. And note: the city's been working on the pump house. Lots of new valves and stuff, and the smell is really much less, if just as bad. I mean, I'm not saying no one cares.

It's a nice place under the crap. The trees are still trees. And up in the trees the Carolina wrens are still Carolina wrens. And the wildflowers are still wildflowers even if they grow from an old chest of drawers. And the piles of stumps are pretty cool to look at. And the great mounds of concrete from demolition projects too, reminding me, actually, of Roman ruins, at least a little. And the sky is still the sky, and the river flows by below with the perfection of eddies and boils and riffles and pools. And the herons are still herons, and squawk. And the sound of the highway is not so different from the sound of the wind (except for the screeching and honking and sputtering). And the lights of the concrete plant are like sunset. And the train whistle is truly plaintive and romantic, and the buildings of the city a mile upstream are like cliffs, and I've heard that peregrine falcons have been convinced to live there. And the earth is the earth, it is always the earth. And the Sun is the Sun, and shines. And the stars are the stars, and the sliver of the waxing moon appears in the evening, stench or no, and moves me. So don't think I'm saying it's all bad. It's not. I'm only saying that the bad part is really bad.

One fine blue day after much spring rain, Juliet and I in joy take the dogs down to Berliner Park, oh, early spring when the trees are still bare (but budded) and all the world is at its barest and ugliest, every flake of the forest floor unhidden, every fleck of litter and offal visible, and the turtles are not yet up from the mud.

We get out of the car next to a pile of litter someone has jettisoned (Burger King gets a nod here, and Marlboro), and walk down the dyke through old magazines and condoms and smashed bottles to the dam to watch the high water of spring roaring over. In fact, the normal fifteen-foot plunge is now only two feet, and the water comes up clear to the platform where we normally stand high over the river to look, laps at our toes. There are percolating eddies and brown storms of water and the unbelievable force of all that liquid smoothly raging over the dam at several feet deep and twenty miles an hour. You would die fast in that river not because it is so very cold but because of the super-complex and violent pattern of flow.

Juliet and I stare through the high chain-link and barbed-wire fence into the boiling maelstrom, absorb the roar wholly, lose our edges to the cool breezes flung up and the lucky charge all around us of negative ions as molecules are battered apart by this greatest force of nature: water unleashed. And so it's a moment before we see the flotsam trap, where an eddy returns anything that floats—anything—back to the dam and the blast of the falling river. And the falling river forms a clean foaming cut the length of the dam, a sharp line, a chasm; the river falls so hard and so fast that it drops under itself. And great logs are rolling at the juncture. And whole tree trunks, forty feet long, polished clean of bark and branches. And whole trees, a score or more, dive and roll and leap and disappear, then pop into the daylight like great whales sounding, float peacefully to the wall of water, which spins them lengthwise fast or sinks them instantly; and they disappear only to appear twenty feet downriver, sounding again, all but spouting, roaring up out of the water, ten, fifteen feet into the sky, only to fall back. Humpback whales, they are, sounding, rising, slapping and parting the water, floating purposefully again to the dam. It's an astonishing sight, objects so big under such thorough control and in such graceful movement, trees that in life only swayed and finally (a century or two of wind and bare winters) fell at river's edge.

And then I see the balls. At least five basketballs, and many softballs, and two soccer balls, and ten dark pink and stippled playground balls and forty littler balls of all colors and sizes, all of them bobbing up to the wall of water, rolling, then going under, accompanied by pop bottles of many hues and Styrofoam pieces and aerosol cans, polished. And a car tire with wheel, floating flat. This old roller hits the wall of water and bounces away slightly, floats back, bounces away, floats back, bounces away, floats back, is caught, disappears. Even the dogs love watching. They love balls, especially Wally, and are transfixed.

And the tire reappears long seconds after its immersion, appears many yards away, cresting like a dolphin. Logs pop out of the water like Titanic fishes, diving at the dam head-up the way salmon do (in fact, you see in the logs how salmon accomplish their feats: they use the power of the eddy, swim hard with the backcurrent, leap—even a log can do it!), leap among froth and playground balls and tires and bottles with caps on, balls and bottles and tires ajumble, reds and blues and yellows and pinks and purples and greens and blacks, bottles and aerosol cans and balls, balls and tires and logs and tree trunks and chunks of Styrofoam, all leaping and feinting and diving under and popping up and reappearing in colors not of the river: aquas and fuschias and metallics, WD-40 blue and Right Guard gold and polished wood and black of tire and crimson board and child's green ball and pummeled log and white seagulls hovering, darting for fish brought to the tortured surface in the chaos of trash and logs and toys, all of it bobbing, the logs diving headfirst at the dam, the balls rolling and popping free of the foam for airborne flights, and tires like dolphins, and softballs fired from the foam, and polished logs, and a babydoll body, all of it rumbling, caught in the dam wash for hours and days and nights of flood, rumbling and tumbling and popping free, rolling and diving and popping free, bubbling and plunging and popping free.

[1]. Home of at least some of the "Friends of the Olentangy," one of whom gave me a call after the first publication of this essay to invite me to plant trees along the river with his group. I said no, thinking it a conflict of at least my interest to get involved with the PR arm of such a large corporation.

[2]. I'm not saying there is any cause and effect claim here, but in the months after the first publication of this essay, the embankment under the catering facility and the grounds immediately around it were cleaned up quite thoroughly, and have been attended to since.

3. There's some kind of valve system here that's been replaced since the first publication of this essay. The new stuff looks pretty sophisticated, and the stench now is quite a bit less, yet still formidable, especially after rain. The pool in the river below stays thawed in winter, and ducks seem to like it.

4. And, come to think of it, a number of green-painted 55-gallon drums, first about a dozen, then a few more each month or so, till there were over a hundred. You have to love the green paint, the purposeful co-optation of environmental-movement symbolism. These barrels disappeared just after the first publication of this essay, though again, I don't claim any connection. And one day I saw the "Neighborhood Outreach" truck from one of the huge local hospitals, an eighteen-wheeler, make its way into the chain-link compound and drop something—what exactly, I couldn't see from my vantage point, presumably some kind of outreach, though!

March 23, 2012

The Wren in the Writing Shack III.

I finally have some photos to post of the wren nesting inside my writing shack. Yesterday Kate Miles visited us here in Wilmington. Kate is the author of the essay, "Dog is my Co-Pilot," that appeared in both Ecotone and Best American Essays, and of the book, Adventures with Ari.

Anyway, Kate had already seen the jelly bean-sized eggs that were in the nest, and we were sitting in the shack and sipping beers and staring out at the nesting swan on the marsh, when the wren flew in, landed on the stick that Hadley calls "the wolf's leg," checked us out, tilted its tail, and hoped into the nest. And the bird turns out not to be photo shy. Here are the results…..

March 22, 2012

Nothing But the Truth!……Or Maybe Not…..

I swore I would not be drawn into the latest round of the "truth in non-fiction" debate, but as someone who makes their living teaching "creative nonfiction" it's hard not to give in to the pull. The other day I wrote a comment on Brevity's Facebook page: "The truth (!) is that if you have worked in this genre for a while it is really quite easy to be both artful and accurate. A simple introductory phrase, a framing, takes care of everything. It's a joke really. Like listening to skiers on the bunny slope debating about what it might be like to go down the black diamond trail……."

I swore I would not be drawn into the latest round of the "truth in non-fiction" debate, but as someone who makes their living teaching "creative nonfiction" it's hard not to give in to the pull. The other day I wrote a comment on Brevity's Facebook page: "The truth (!) is that if you have worked in this genre for a while it is really quite easy to be both artful and accurate. A simple introductory phrase, a framing, takes care of everything. It's a joke really. Like listening to skiers on the bunny slope debating about what it might be like to go down the black diamond trail……."

I have grown increasingly strict with myself when it comes to my work. But I'm not so strict with others. A few years ago I was on panel about just this subject with three other writers, Philip Gerard, John Jeremiah Sullivan, and Bill Roorbach (aka Bill). Quite accidentally we sat ourselves down at the table in the order, from right to left, that we believed that nonfiction must be factually accurate. I believe Philip sat on the far right, John next, then me, and Bill on the far left. Philip is a friend and I just had the pleasure of reading his great new book of essays (The Patron Saint of Dreams, published by Hub City Press) but he was once a journalist and so doesn't see why it's so hard to be both artistic and accurate. And why not? My own position has moved steadily in the direction of fact, to the point where if the panel were held today I might be sitting on Philip's lap.

But I still respect Bill's refusal to heed the more strident orders of the fact police, and his insistence that this is a genre that should be subjected to standards of its own, not those of journalism. The most obvious example is remembered dialogue from childhood, which brings us right back into the hazy halls of memory.

That said, anything of that sort can be handled with proper framing, as I suggested in my Brevity comment.

That's how I feel today. But here's something from my old lefty days, back when the James Frey thing broke and he was brought before Oprah to publicly confess his crimes.

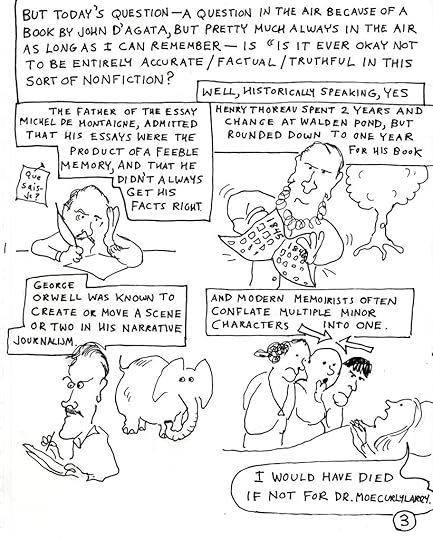

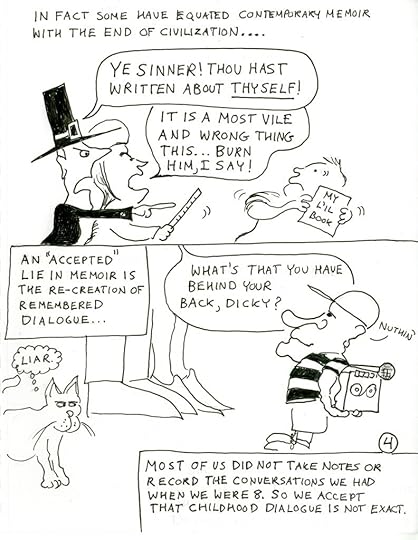

Against a Literature of Fact

Long before anyone had ever heard the name Frey, there were those who equated the rise of memoir with the end of civilization. Several years ago, for instance, James Wolcott of Vanity Fair used the lingerie-and perfume-filledsoapbox of his magazine to preach that most memoirists are whiny narcissists, navel-gazers who write about victim subjects like child abuse or cancer or watching their fathers die. I took offense at this, maybe in part because I'd just written my own navel-gazing memoir about the death of my father, but also because I couldn't help but feel that Mr. Wolcott's adopted role as stern preacher was blinding him to what was really going on in the diverse and dynamic world of contemporary nonfiction.

A similar blinding has occurred over the last three weeks as we've heard a scolding chorus issue forth from dozens of columnists, commentators, and of course from the great benefactor herself. "I believe the truth matters!" thunders Oprah as the crowd cheers. Something must change! Facts must be checked! Off with his head! Of course we all agree that Frey was wrong to have lied, to have made things up whole cloth. But in the moral oversimplification of the moment, everyone seems to have forgotten that our culture has a long proud tradition of fictional nonfiction. Ignoring this tradition, not to mention ignoring the fact that most of us understand that memoir is not always literal truth, we all found ourselves outraged, outraged, that we had been lied to. The collateral damage became obvious when Oprah's next book, Elie Wiesel's Night, came under attack for factual details, most prominently the age that the narrator was carted off to Auschwitz. That there is a world of difference between this inaccuracy and those of Frey, that to compare the two books would only be reasonable if Wiesel had invented the fact he was in a concentration camp at all, didn't matter. What mattered was the emerging belief that memoir should be held up to the rigorous journalistic standards of factual accuracy.

I humbly defer. In fact, despite all the recent handwringing, I contend that we are in the midst of a golden age of imaginative nonfiction, and that while much of that literature isn't factual in the journalistic sense, it also doesn't need to be. During the same week that Freygate broke, I began teaching an annual class to undergraduates on the history of literary nonfiction from Montaigne to the present. Montaigne's work, begun in the 1570s, signaled not just the birth of the essay but of an attitude, putting the self on display to reveal the contradictions of self, and hoping to achieve, through candor, the intimacy which the essayist Philip Lopate calls "the hallmark of the personal essay." One could argue that Montaigne's chronicling of his own every move was the closest thing the 16th century had to reality TV, and in fact Montaigne painstakingly revealed the particulars of his life, including his bowel movements, (if James Wolcott wants to slam someone, here is his man). But he does so with the belief that "Every man has within himself the entire human condition." That is, by talking to and about himself he is, to some degree, talking to all of us.

Obviously Montaigne's attitude suits these times, and I contend that in recent years something creative and vital has been unleashed in the world of nonfiction. Yes, there have been some sappy recovery memoirs, though I dare readers to name three other than Frey's. But more to the point we have had the essays of James Baldwin, Joan Didion, and Wendell Berry, the wild comedy of the not-always-factual New Journalists, notably Hunter Thompson and the young Tom Wolfe, and honest, hard-minded memoirs like Tobias Wolff's This Boy's Life and Philip Roth's Patrimony (as powerful as any of his fiction, though one could argue that his fiction is also Montaignian) and more recently the experimental nonfiction mosaics of writers like Richard Rodriguez. This is no less than a flowering and these authors, and dozens more, provide a growing sense and obvious proof that the actual facts of one life can be arranged in ways that rival the best fiction. And believe me they are arranged. While none of these writers simply made things up, as Frey did, they all, to a varying degree strayed from the purely journalistic version of truth. On the other hand, they are the true literary great-grandchildren of Montaigne in that honesty is their first virtue. "The mind is a burrowing organ," said that fine creator of creative nonfiction, Henry David Thoreau. The work I'm describing isn't lurid, sensationalistic, or sloppy. It is the hard work of burrowing into one's own life to make stories.

Though there is a long tradition of imaginative nonfiction, we are now entering a new place of cross pollination between the essay, memoir, reportage, biography, and fiction. At the birth of any form there is always sloppiness and uncertainty of rules. Perhaps that is best exemplified in the last writer I teach in my course, whose book, A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, came out almost 425 years after Montagine's. While at first glance Dave Eggers and Michel de Montaigne might not seem to have much in common, they both explore the world through exploring themselves, stripping selves away, remaining skeptical about a thing called truth while bumbling, Colombo-style, toward honesty. In fact the prefatory section of Eggers' paperback version of his book self-consciously anticipates the backlash that Frey apparently went whistling by, acting as a pre-emptive strike against accusations of self-aggrandizement and dishonesty. This begins right on the copyright page where Eggers admits, "This is a work of fiction, only in that many cases, the author could not remember the exact words said by certain people, and exact descriptions of certain things, so had to fill in gaps as best he could." The effect of these words, in contrast to the secretive, Nixon-ian air of the guilt-ridden Frey, is refreshing, like talking with a friend who inspires trust by honestly admitting past lies.

Oprah may tell us the truth matters, but the truth is it's not that simple. Every seasoned reader, even Maureen Dowd, must know that the memoristic contract with the reader is quite different than the journalistic one. Anyone who sits down to read a detailed account of a conversation a memoirist had when he was thirteen with his mother over the death of a goldfish, should know that what is on the page is made up, or as we say in the trade, re-created. Astute readers also know that within the world of memoir there are lies and then there are acceptable lies. As Bill Roorbach, another daring contemporary writer of nonfiction, says in Writing Life Stories: "Approximating the words from a lecture attended long ago at your modest college is something quite different from saying you studied under Robert Lowell at Oxford." Another historically "acceptable" lie is time compression. I recently published a book of nonfiction about the great nature writer John Hay, and I taped many of our conversations. But when it came time to novelistically frame my time with this man, I decided it was better to have our meetings take place over the course of a single year, rather than the sloppier two years and change that it actually took. My justification for this was fairly highbrow since mine was a nature book and for a model I could point to Thoreau's Walden, which had also been squashed down from multiple years into one. Not a lie, true, but it may keep Thoreau and me off future Oprahs.

Sins of time and dialogue may seem relatively minor. But then we get to human beings, who inside our pages become something called characters, and this is where it gets messier. Omission is one of the lesser crimes of character: I have an essayist friend who wrote a beautiful piece about experiencing a moment of euphoria after climbing a mountain alone. The only problem was that the companion the writer had actually been hiking with read the essay and grumbled about being edited out. Equally common is creating something called composite characters, when several real life people are smushed into one. This is usually motivated by a desire for clarity and artistic neatness among minor characters: say you are writing about a time when you were in the hospital and you conflate three night nurses into one. Students of mine once read the work of a memoirist who later, when he came to speak to us, admitted that a minor character they had all really loved had actually been built in this way, from the parts of several characters. They felt understandably betrayed.

Of course the simplest way for an author to use these techniques without upsetting readers is by fessing up. A major complaint about Frey's book is that nowhere did he say or suggest that it wasn't all true, that he in fact rode the "true story" horse hard until it bucked him. The paradox within the genre is that while we may forgive a few misplaced facts, we never forgive an overall lack of honesty. As it turns out one of the surest and most obvious ways to establish this honesty is by telling the reader right at the start that what follows may not all be exactly true, and within the genre disclaimers have risen to a kind of minor art form. For instance, at the beginning of This Boy's Life, Tobias Wolff writes: "I have been corrected on some points, mostly of chronology. Also my mother thinks that a dog I describe as ugly was actually quite handsome. I've allowed some of these points to stand, because this is a book of memory, and memory has its own story to tell. But I have done my best to make it tell a truthful story."

This last point is a vital one. Intention may be hard to discern and somewhat vague, but intention matters. One of the reasons for the Frey backlash is the sense of many readers that they were manipulated and betrayed, and that Frey's motivations were not honorable ones. In the best essays or memoirs we feel just the opposite: that the writer is honestly wrestling with ideas and then trying to present them to us as nakedly and frankly (and artistically) as possible. A good memoir becomes great when we sense this honest effort to make sense of life's facts. Can readers be misled? Lied to? Can candor be used as a false trick, the way really good liars use it in life? Certainly. But we also hope we can ferret out intention, and, more importantly, that we know when something is art. (Long before the recent revelations about Frey's book, many reviewers commented that certain things didn't feel true.)

If in the aftermath of the Frey scandal nonfiction writers are held closer to journalistic standards it will be for the most part a very good thing. But it would be a shame if this were taken too far. The fact that the rules within memoir are not as rigid is one of the most exciting things about the genre, and that excitement has given us both the New Journalism and the lyric essay. There is plenty of fact out there for anyone who wants it; in our society the onslaught of journalism is constant and unabating. Take a look at any book review page and you'll see that never before has there been such a profusion of factual books about some subject, usually, since 9-11, about war and politics. But there are those of us still hungry for life stories, and for whom stories made from real life are the most fascinating. Samuel Johnson wrote of how readers like to read about the lives of others in part so they could "put to use" what they read in their own lives. This, too, is part of the hunger for lives.

In The New New Journalism, Robert Boynton claims that our best contemporary nonfiction writers are our journalists who follow "the great issues of the day." But great issues fade and what is most boring in Montaigne isn't his analysis of his bowels so much as his descriptions of the French Civil Wars. Boynton claims that the "days in which nonfiction writers test the limits of language and form have largely passed." Clearly here he is only referring to journalism, because within the world of the essay and memoir some serious testing is going on. Things are wide open. On the hallway where I teach there are three other professors who teach so-called creative nonfiction and I know that we all have widely varying opinions about the degree that this sort of writing should be absolutely factual. This might be confusing, not just to the students but to ourselves, but it is also exciting. There is always danger on the frontier. The rules aren't clear yet. The form has not calcified.

Should our stories be as factually accurate as memoirists and essayists can make them? Of course. Just because a thing is emotionally true doesn't mean it can't be factually true, too. But at the same time a memoirist who says their sister had blonde hair when it was light brown shouldn't be held to the same standards of Stephen Glass. It is the nature of memoir and essay that memory is telling the story and these forms will never be as clean as journalism. In the best literary nonfiction the true rules that need to be followed are artistic ones. Those rules are developed in each individual book by each individual artist, and they should be judged that way, individually, not in a great hue and cry of moralistic oversimplification. Yes, it is wise for writers of memoir to hew as closely as they can to the facts. But my worry is that we will, as usual, overreact and learn too literal of a lesson. That in rushing to rein things in we will choke off what is creative and alive in the form.

March 20, 2012

Bad Advice Wednesday: Guest Contributor Joshua Bodwell

This Won't Hurt A Bit

.

This piece by MWPA director and all-around good guy Joshua Bodwell appeared originally in Maine Ahead, and speaks directly to business leaders, nice idea: Hire a writer! And of course Bill is available for any type of surgery. Bring your own hospital gown. Bill has a Leatherman and a hack saw. Dave is in charge of anesthesia. Rates are competitive with the best garages.

.

Please, Hire a Writer

My pal Bill Roorbach is an exceptional storyteller. He is descriptive yet concise on the page, and perfectly meandering when he shares a story over a beer.

There is one particular story Bill has told for years, and I often think of it whenever talk turns to good writing and what it means to write well. Bill's tale has become something of an urban legend, and it has been retold at literary conferences and parties across the country.

The short version goes like this: Bill is at a literary cocktail party. A surgeon approaches Bill and tells him she was so inspired by his lovely, understated memoir Summers with Juliet that she is going to take a six-month sabbatical to write her own book. Bill politely thanks her; this isn't the first time he has heard such cavalier pronouncements about writing.

"You know, you've inspired me!" Bill suddenly blurts out, his courage no doubt girded by the cold liquor in his tumbler. "I'm going to take six months off and become a surgeon like you."

Confused and unamused, the surgeon walks away.

Now, Bill's response was, of course, pitch-perfect, tongue-in-cheek sarcasm. But it points out how casually many people talk about the hard-earned craft of writing. While it's commonly accepted that every skill set—be it surgery or stonemasonry—requires practice, hard-won expertise, and years of experience, why do we keep forgetting this is also true of writing?

Joshua Bodwell

No one assumes that just because they own a gleaming set of wrenches they are proficient auto mechanics. We accept that we are enthusiastic amateurs fumbling our way through a Sunday afternoon under the hood. So why is it that so many people with a word-processing program fancy themselves wordsmiths?

The fact that most of us can write does not necessarily mean that we are all writers.

In a wrld whr ths knd of mssg hs bcom accptbl, good writing is actually more appreciated and more important than ever. Good writing is good communication—and just about everything in today's small, flat world is about communication. Just consider the sheer volume of writing used to communicate a business: website content, print materials, advertising, and, yes, gobs of email. Good writing is good business, and good leaders value genuine expertise, invest in their most important assets, and never assume there's no room for improvement. Whether it's in our relationships or our professions, it's never wise to take something important for granted.

While mechanics work in the esoteric language of carburetors and exhaust systems, a writer's tools are the 26 letters and 14 common punctuation marks that make up the English language. But here's how that equation looks in literary terms: 26 + 14 = an infinitude of possible expressions.

All of this is to say, simply, that written language is slippery. The ability to speak well is not the same as writing well. Casual emails, texts, and Facebook posts are not professional-grade writing. And getting someone to pay attention to your product or service or cause, in a world filled with noise and distractions, is an elusive art. Yet if we accept a few fundamental facts, respect the written word, and strive for improvement, we can all become better communicators.

1) Make good writing a priority, not an afterthought. Recognize that great businesses and organizations are built on great communication.

2) Invest in your written communications. Build it into your budget. Take time to get it right. Refine and improve your writing over time.

3) Don't do it alone. Take what you have, print it out, and give it to friends, colleagues, or clients for their feedback. Good writing never occurs in a vacuum.

4) Always pass it by a professional! If you can't afford a professional copywriter for your print materials or online content, for example, work with an experienced editor or proofreader. Professionals see things that novices overlook.

5) Remember that bad writing is bad business. Typos, ungrammatical sentences, or missing words imply carelessness and substandard quality. And confusing or sloppy prose is as disrespectful to readers as rudeness is during a conversation.

6) Never, ever, under any circumstances, use the typeface Comic Sans.

Good writing is, at its very best, invisible. Like great typography and great architecture, even when you're not fully aware of good writing, you are imbued with a sense of ease and calm. Nothing jars, clanks, or confuses. Good writing flows, lures you in, and exhilarates.

The surgeon Bill Roorbach met at a cocktail party was correct in one sense: Nearly everyone can write. But it's careless to assume that everyone can write well. So what's one to do?

When your car engine is smoking, you take it to the shop. When your kitchen sink is leaking, you hire a plumber. So when dealing with something as crucial as the language you are using to describe your business, services, mission, or cause, hire a writer.

We're out here, still awake in the predawn hours, sleepless over a semicolon or sloppy adjective. We're obsessing over a typo or stray comma the way a great CFO obsesses over a balance sheet. So, please, hire a writer. Either that, or my pal Bill is going to start performing surgery.

Joshua Bodwell is the executive director of the Maine Writers & Publishers Alliance. His website is www.joshuabodwell.com.

His cartoon head was drawn by his partner Tammy Ackerman.

Cartoon of bill by M. Scott Ricketts

March 19, 2012

Vernal Equinox

23.4 degrees

Here is the equal night again, so different from that of autumn, which comes dressed in summer. In fact, the first day of spring comes to Maine in high winter drag. Often it comes dressed in snow, thick and wet, mixed with rain.

For me in March most of the pleasure in watching snow accumulate has fled. I decline to shovel the driveway, thinking, Snow'll be gone soon enough, and pay for that when the slush left over freezes in deep ridges that last weeks in a cold snap. I consider the skis—but the snow is so wet and heavy, and I've been thinking about my bicycle, my hiking boots. Soon enough.

But, of course, it's not soon enough. It's weeks, sometimes, in grinding cycles of melt and freeze, and melt and freeze again. And again. Time never moves so slowly as in the transition from winter to spring in Maine. By March the mind's night has got very long, and I have gotten used to it, gotten cozy alone in there, in my thoughts. Winter is painful at times, but comes at least with its own anesthetic: cold slows all processes. Spring is more painful: growth. It's hard to let the branches come forth, to anticipate the work of putting out all those millions of leaves. But it must be done. The sun is bright that one morning that breaks the back of winter—the air is cold, to be sure, still in the twenties. I dress for a walk as for winter, come indoors sweating, half disrobed—by ten o'clock it's forty degrees. By noon, fifty, the sun higher and hotter than I remember possible. Out of the wind down in the stream bed, standing on old bright snow covering old familiar ice, I'm hot. The jacket comes off, the sweater, the flannel shirt, all but the t-shirt underneath (not one picked for show, that old shirt with the hole in the shoulder, the blue swath of door paint, the stupid slogan from the marathon one never ran: "Hang in There for Hugs!"). Everything is adrip. The chickadees, ever cheerful, find high perches and chip and buzz and whistle their pleasure. Sparrows, too, who sing theirs. The cardinal sets himself up on a good high branch and begins his spring song, in a Maine accent (that is, sings a regional song, distinctly different from cardinal song in Ohio), still hoping to impress his gal, despite being her life partner: chew, chew, chew, woody, woody, woody, chew.

After that fateful day, the temperature gets to just a little above freezing, almost every day. The world around is at its scruffiest—the load of snow has pushed down every dead thing, every stalk and leaf and twig of the summer past, flattened the forest floor, flattened the lawn (which emerges afternoon by afternoon in patches, muddy and golden). The odd fleck of green comes as a surprise: blade of hardy sedge, wood fern, branch of pine. The snowpack lingers in the shadows on the north side of the house, crumbles gradually into corn—I walked on top of it just yesterday without a thought: solid ground. Today I sink. The compost heap by the stone wall at the verge of the woods emerges in mussed layers—frozen rinds from as far back as November down there, frozen peelings and stalks and cuttings and food scraps from each month since, soon to be proper wormfood, food for bacteria, too (more quickly than one would guess) gorgeous black soil. Red knobs show in the dirt where the rhubarb will rise. Green hands reach up everywhere from tulip and narcissus and crocus and snowdrop and hyacinth bulbs I planted so long ago I can't think when or quite remember where.

Down in the stream, the mysterious beavers leave sign that they are venturing forth: clean-gnawed, waterlogged branchlets in pick-up-sticks piles underwater along the banks, the bones of their winter meals. The biggest might be about big enough for a walking stick; I fish it out of the shallows, walk with it, enjoying the feel of smooth-peeled wood.

The woodpecker—one of our hairys—leaves large wood chips on the ground—he's chiseling a house from the trunk of a popple tree half killed by the success of a tinder polypore (which is a common fungus, a conk with fruiting bodies like so many horse-hooves kicking out of the bole of the tree).

What is it makes us open our hearts in spring? The sun hits my chest in town and I linger on the sidewalk in front of the Witt Brothers' Rexall—suddenly I don't mind talking with whomever's walking past: a long and textured list of acquaintances coming out of hibernation, blinking. The daylight seems endless, though the day is exactly half night. I feel the old sense that everything has come into balance, every odd thing of winter, another hoop closing. My night nature no longer overpowers my sun nature, my natural optimism is back.

And will be rewarded with light—every daylight will be longer from here on in till solstice. The westward creep of the sunsets along the ridge of our view is a movement away from solitude, away from cabin fever. And here's a hooray for the presence of others! The brooks flow everywhere. I hear them and my heart pumps harder; I'm a stream again, and no longer ice.

[From Temple Stream: Dial Press]

March 17, 2012

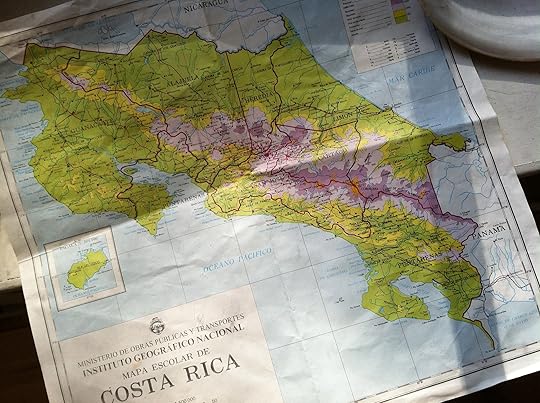

Getting Outside Saturday: Learning the Island

LEARNING THEISLAND

LEARNING THEISLAND

Journal Entries from my first year in the South and My Daughter's First Year

September 28

The swallow migration is coming through. These shield-like aerodynamic birds dip and shoot over the sea oats like hallucinogenic flecks. Meanwhile the sanderlings work the tideline with their sewing machine bills, searching for mole crabs, while Black Skimmers get active at dusk. The skimmers let loose a noise like the wahh-wahh-wahh. of adults talking on Charlie Brown.

On the way in to work this morning I saw a bumper sticker on the back of a pick-up. Other details hinted that the truck was owned by a hunter, but it was the sticker that really gave it away. It read:

"If it Flies, It Dies."

October 3

There is a tree, more a large bush really but let's call it a tree for today, that stands outside our window that has begun to bloom with monarch butterflies. Dozens of them resting here, feeding, before continuing their preposterous and fluttery migration south. I have watched individual monarchs try to fly from our island southward over the water, have watched them dip precariously low, almost touching the sea, which would be the end of them, before carrying on apparently unperturbed by their thin brushes with mortality.

Inside the house Hadley thrashes on her changing table. Her legs have always been strong, even when she was inside her mother I would feel her thumping against my back at night. Now trying to change her is like attempting to subdue a landed striper with your bare hands. She sleeps in the bed between us at night and to make sure I'm there she will occasionally administer a swift Kung Fu kick to my middle.

She also seems to have inherited my obsessiveness. Sitting in her high chair she keeps a death grip on her little plastic spoon, refusing to unclench and let you fill it with baby food for another bite. The only way to get it out of her hand, short of prying it open, is to trick her by using that same obsessiveness against her. You offer another spoon from another direction and when she locks on that one, grab the first away. And so her obsession isn't eased as much as transferred. As if her mind were swinging from vine to vine.

October 9

The monarch tree continues to bloom.

The joy—the relief!—of a beach town emptying. It happens much later here than in the north, but, as we are learning, it does happen. Fewer cars in the lots, fewer walkers on the beach. I remember the joyous feeling on Cape Codwhen you could finally re-claim the beach after the crowded summer. To be less cramped, to have more space, to be able to turn away from people and toward yourself and your own.

October 22

More small death to report from the neighborhood:

The other day at school a woodcock flew straight into the front door of the Creative Writing building. The noise was like that of a baseball being struck. A solid thwump. The bird was dead by the time I picked it up. Its underside was tawny and beautiful. And to my eyes, the eyes of a shorebird-lover, it looked like an inland willet.

Today I am sitting on the dock in front of our house. Next to me is a quaint little sailboat called "Screaming Banshee" and a powerboat called "Mello Yello." I feel the urge to ask the owner of the latter boat what kind of statement he is trying to make by dropping the "w"s from the ends of the words. Docked next to it is a cabin cruiser called "Fishin' Mortician II."

On the next dock down there's an old black guy fishing. He wears a flannel short and sits on a bucket that looks much too small for his bulk. I am on the next dock and watch him pull in a fish. It's too small and I wonder if he will throw it back. I'm relishing this romantic scene–rustic, southern, pastoral–when I see him grab the fish by the tail and slam its head on the dock, then toss it back in the water before throwing his line back in. I watch the tiny fish float by on the current.

Later, after I see him do this a couple of more times, I wander over to his dock and ask him about it.

"Don't want to catch those little fuckers again," he says.

October 29

The latest lesson the world has taught Hadley is that things exist when they are out of her sight. This is called "object permanence" and, until we comprehend this notion, out of sight is out of existence.

Cause and effect is another idea that is starting to take hold. Those spoons, gripped so tightly just weeks ago, are now being dropped to the floor as she conducts her own little science experiment. Or as Dr. Sears puts it: "An important part of a baby's reach-grasp technique is developing the ability to release the grasped object. Babies become fascinated with holding something, such as a piece of paper, and then opening their hand and allowing the object to drop to the floor." And so go sixteen plastic spoons.

Meanwhile the Monarch tree has emptied. But unlike most leaves, these haven't merely fallen to the ground but decamped and begun a two thousand mile migration toMexico.

November 3

After Hadley and I make our morning pilgrimage to the coffee shop, I turn to the paper. On the front page I read of the Iraqi man whose wife and two daughters were killed when their house was blown up "by mistake." This is tragedy, obviously, but we are Americans and we believe that tragedy can be rectified. The soldier who made the mistake offers the man an apology. And ten thousand dollars.

There are so many things that have been offensive about our media presentation of the war that it's hard to pin point any one thing. But perhaps most reprehensible has been our habit of listing the number of people dead, and then only listing our dead.

November 9

The magic trick of a loon. You look over at it, look it in the dark eye, and then you look away for a second and turn back and –poof—it's gone. No sign of it in the air or floating on water, and in fact no sign of wake where that it has submerged, though you know that's what it's done. It has tunneled down into another world, another life. The best trick around.

Considering that I am a new father with a new job, I spend an inordinate amount of time on the beach watching birds dive. I can't help it. As a sports fan and someone who enjoys contact, I love the sport and variety of it. The pelicans, for instance, are alternately ungainly and graceful. They dive from up to 65 feet, and they hurtle downward out of the air with a great twisting plunge. This is just one way that their dives are different than the birds I am used to in the North. Of course there are really two dives within the dive of any water bird. First, there is the initial drop from the sky and then there is the entrance into the water. Each species enters from different angles and with different styles, strategies, and goals. A northern gannet will accelerate and hit the water like an arrow, leaving air behind, using gravity and a last thrust of the neck to spear through the surface before tunneling down underwater where they chase after fish in their own element. Meanwhile an osprey dives head first before swinging its legs forward and–like the one I saw the other day–popping a wheelie at the last second, going in talons first.

The weather has warmed but the clouds of gannets remain. The other day, watching them, I decided I needed to get closer. Pelicans circled on the water in a great post-dive scrum, while the gannets dived closer than I had ever seen them before. I stripped off my clothes and swam out in the middle of the scrum. Numb legs were a small price to pay. I had never seen the action so close, a front row seat. As the birds dove just a dozen feet away I had a fish eye's view.

November 18

Today the temperature dips down into the low thirties and I feel relieved. It's as if my brain is activated, waking up from a long hibernation, and it is easier for me to work on the book, to place the characters that I have been, to this point, only sluggishly imagining.

I glass the horizon and focus in on one gannet, studying the art of its dive. It flaps and waits, with a hundred other of it kind, searching for fish below. A gannet doesn't need to have the patience of an osprey, which is going after a single fish. Instead these white birds, with their six foot wingspans, just hit a general area where fish are schooling. What they may lack in pinpoint accuracy, however, they make up for in abandonment. They pull their wings in and let gravity do its work, throwing throw themselves into their dive. What does it feel like, that cold moment of contact, of immersion, entering into the dark wetness and immediately giving chase to animals who only know this one liquid realm? What skill to both dive with Olympian grace and swim well enough to overtake fish! To be equally at ease in both worlds. And then, and here is where they differ from ospreys and even the more stolid pelicans, to do it again and again and again.

November 22

Montaigne died in 1592. Over the last three days of his life he lost the ability to speak and could only communicate by pen. One imagines he scribbled furiously.

What is writing if not an attempt to leave our marks?

In a macabre fashion our cat Tabernash has done just that. Despite recent rains, his blood still stains the road in front of our house from where the SUV slammed into him and didn't stop.

Our babysitter saw it all and called Nina who ran home, cradled Tab in her arms, before rushing him the vet. He didn't make it, which leaves more than one stain on our new home. I am not a cat person, and as a bird lover I know well the carnage cats are capable of, but Tabernash, an adopted stray from Boulder Colorado who spent his early years living in an abandoned motor home, had earned my grudging respect and love. He had been with us through all our moves, from Colorado to Cape Cod to Carolina, and thought we worried that he might be jealous, or even predatory, when Hadley was born, this did not prove the case. He would nap with her in the afternoon and press his forehead gently against hers when she woke. (Hadley still thinks this is how you greet any animal and if we come upon a dog in our walk she will lean in her head.)

A few weeks before Tab died, Hadley was napping in her bedroom when my wife, who was downstairs, heard a maniacal purring come over the baby monitor. She ran upstairs and found Tabernash lying right on top of Hadley while Hadley, grinning ear to ear, waved a fistful of yellow fur.

December 6

School's out forever. School's out for winter.

My first term is over. A month to become a writer again. To wear my sweats all day long and drink too much coffee, to stop brushing my hair and answering the phone, and to descend every morning into my writing cave. So different than the friendly-wave-hello, help-others work of teaching. Fuck that for now. Melville said of that deep writing state that it was the "strange wild work." That's where I want to go.

December 12

Seven hours at my desk this morning. Feeling like myself again. And soon a week back on Cape Cod.

The big news from the outside world is that a Northern Right Whale is patrolling up and down the coast. Today Hadley and I watched from the pier as water spouted out of its blowhole. Sleek and black, its enormous dorsal fin juts from the water like the keel of a capsized schooner. The Right Whale earned its name because it was considered the "right" whale to hunt, both easy to kill and bloated with oil. This led to its current distinction as the most endangered of all large cetaceans with only about 300 Right Whales left in the world. And though no one is hunting this particular whale, curious boaters keep getting too close, forcing it to dive under to avoid them. I find myself rooting for it to breach right under one of the smaller boats.

January 25

I love our local coffee shop but there is a problem in that it doesn't keep regular hours. This is especially troubling when it comes to something as regularly needed as coffee.

I have been shipwrecked. Thrown up by the waves on this strange island. We are separated from the mainland by a drawbridge, and lately they have been doing repairs at night so that it's impossible to get off the island after ten. When I do drive off, early in the morning to work on the computer at school, I encounter one of the strange new customs of this place. My fellow drivers all float along, driving under the speed limit, seemingly unconcerned with getting anywhere. I had expected rowdy redneck drivers in this land of NASCAR, revving up their engines at the lights, but instead they drive as if stoned. They float up to the lights, unconcerned, uncaring, untroubled. A few mornings ago I watched a middle-aged man, his eyes blank like a goat's, as he stared at a green light for a full ten seconds. I was so fascinated that I didn't even hit my horn. "It's as if the whole town were just learning to drive," Nina says.

Thinking about the traffic gets me thinking about other sorts of movement. Place, I've decided, is a perfect metaphor for ambition. The ambitious, by definition, want to be some place other than where they are. Yes: Ambition is moving from place to place versus being content where you are. Goals, those things that lead us to the new place, are the maps. By this definition our local drivers are underachievers. The man with the goat eyes that I watched at the light seemed distinctly uninterested in "getting ahead." Of course I bring my own regional mores down here with me. Trained to drive in Boston, I'm a caricature, too, just the sort of outsider that the locals must loathe. I mutter and curse because I am "stuck" at a light; I speed ahead so I can be some place other than where I am.

February 3

One thing I can't stand about this place. People here use beach as a giant ashtray. They finish their cigarettes and toss them into the sand where kids will soon be playing. Unfucking believable.

On the bright side, this morning I saw an Eastern bluebird with orange breast cracking a nut open on top of a lightpost.

February 20

Pelicans are not the only thing that patrol these skies. Today my bird-watching is interrupted by a noise so loud it seems the sky will crack open. The beach's illusion of the carefree is broken by the sight of 6 huge black planes. FortLeJuneis eighty miles up the coast from us. Occasionally it isn't pelicans, but F-22s that fly over the beach in formation. For many of these soldiers this is the last stop beforeIraq. Looking up, you can't help but imagine what it would be like if they were an invading force, patrolling the skies of your own country.

March 10

I am still a long way from calling this place home. For one thing I'm not ready to fight for it yet, with its ramshackle architecture just waiting for the next hurricane to blow it down, and its miles and miles of strip malls. Back onCape Codit was a constant fight, with many losses and much pain, watching what you loved disappear. I'm not committed to this new place, just a visitor, though for now I like that well enough. It's nice to take a short break from caring. I know that soon enough, if we stay here, this place will start to get in my blood and start to operate on me the way the Cape still does. It will ask me to defend it, and how will I be able to say no?

But for now I am content to wander through this shabby wilderness. Yesterday Hadley and I found a gull tangled and trapped in fishing line and we went home to get scissors to free it. Then last night I went out on the boat with Douglas, a grad student of mine who works as a charter fisherman. Not long ago Douglas saw a pod of 50 bottlenose dolphins, with babies swimming in and out. Yesterday he took me out on his boat, ostensibly to fish for false albacore but actually to help me get a sense of the island from off-shore. It was a rough afternoon and we saw petrels dip and dive into the wave and a razorback shoot low over the water. These, like gannets, are birds I always associated with the North, looking more fit for swimming than flying though this one shot through the trough of the waves on frantic missiles. At the very least it must have been on the far end of its southern range; it looked like a miniature penguin with a chunky body and black wings with white breast. We also saw Ibises, buffleheads, mergansers, scaup, mallards, loons, oyster catchers. Later he showed me a school of fish squiggling and igniting sparks of phosphorescence by the jetty wall. There was more phosphorus in a long wave that rolled in like a train along the breakwater, roaring and glowing green, before it crashed white over the wall.

Today I watch a hundred pelicans close to shore and several hundred gannets behind them, as they dive for fish. That is the secret of all this bird life: the wildly abundant fish life. The air fills with a crazy, jangling energy as bird after bird dives. The winds blow the top of the waves back over themselves, the white blown backward like smoke. The water broils with birds. Thousands of gulls, gannets and pelicans feasting on bait fish.

March 15

Watching Hadley's day-to-day growth reminds me of a summer I spent watching osprey nestlings fledge. More than we know, humans delight in the simple observance of growth.