David Gessner's Blog, page 88

April 18, 2012

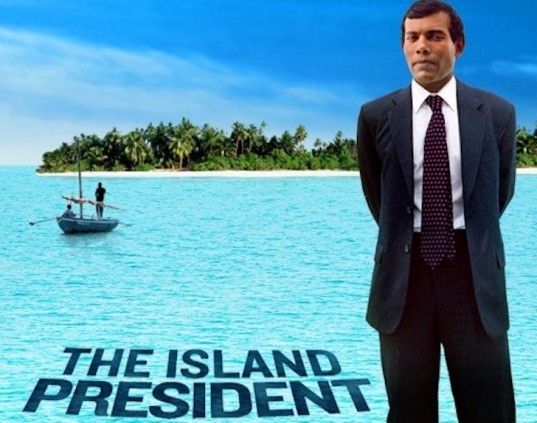

A Night at the Movies: “The Island President”

President Mohamed "Anni" Nasheed

.

Another trip over to Railroad Square Cinema in Waterville, Maine, to see Jon Shenk’s The Island President, a brand-new documentary featuring the incredibly charming and very courageous (and sadly now former, after threats of violence and a coup d’etat) president of the Maldives, a 400-mile chain of 2000 inexpressibly beautiful (as the film shows) islands off the southwestern tip of India. The movie, though, is sad: the Maldives are in imminent danger of sinking under rising sea levels as global warming proceeds unchecked. The happy part is that a man like Anni Nasheed, the president of the film’s title, exists. After the screening director Jon Shenk came onscreen via Skype to take questions. More courage and plain intelligence. One thing he told us was about a reporter asking President Nasheed about the role of hope when it came to climate change and other world problems. “I don’t hope,” the president answered. “I work.” Mr. Shenk also invited us to spread the word about the movie and about their website, which I duly do here. It’s a beautiful movie, worth seeing on any basis, but as a call to action it’s unbeatable. Please beg your local art theater and colleges to bring it to town. And see it yourself. And spread the word. The Maldives–a meter and a half at the highest point–are sinking. And as President Nasheed points out (walking in New York on the way to the United Nations campus), Manhattan won’t be far behind.

.

Here is the synopsis from the official THE ISLAND PRESIDENT website, which I quote whole in the hopes it will catch your interest. A great movie:

“Jon Shenk’s The Island President tells the story of President Mohamed Nasheed of the Maldives, a man confronting a problem greater than any other world leader has ever faced—the literal survival of his country and everyone in it.

“After leading a twenty-year pro-democracy movement against the brutal regime of Maumoon Abdul Gayoom, surviving repeated imprisonments and torture, Nasheed became president at 41, only to encounter a far more implacable adversary than a dictator—the ocean. Considered the lowest lying country in the world, a rise of a mere three meters in sea level would inundate the Maldives, rendering the country practically unlivable. Unless dramatic changes are made by the larger countries of the world, the Maldives, like a modern Atlantis, will disappear under the waves.

“As much as its plight is one-of-a-kind, the Maldives itself is a country like no other. A Shangri-la of breathtakingly beautiful turquoise reefs, beaches, and palm trees, the Maldives is composed of 1200 coral islands off of the Indian sub-continent, of which 200 are inhabited. Arrayed across 400 miles of open sea like necklace-shaped constellations, the Maldives is one of the most geographically dispersed nations on earth.

“Democracy came to the Maldives, a Sunni Muslim country, in 2008, in a way that was uncannily similar to the recent Middle Eastern populist revolts against autocrats in Tunisia, Egypt, and elsewhere. What made the Maldives movement different from the ones that have followed it is the existence of a clear opposition party, the Maldivian Democratic Party (MDP), which had in its co-founder, Nasheed, a popular and charismatic leader ready to usher his country into democracy. Educated in Sri Lanka and England, Nasheed proved to be an unusually shrewd and sophisticated politician who grasped that the only way he could stand up to the catastrophic issues of climate change facing his country would be to take the Maldives cause to the world stage.

“The Island President captures Nasheed’s first year of office, a time when he influences the direction of international events in a way that few leaders have ever done, even in countries many times the size of the Maldives. Nasheed’s story culminates in his trip to the Copenhagen Climate Summit in 2009, where the film provides a rare glimpse of the political horse-trading that goes on at such a top-level global assembly. Nasheed is unusually candid about revealing his strategies—leveraging the Maldives’ underdog position, harnessing the power of media, and overcoming deadlocks through an appeal to unity with other developing nations. Despite his country’s dire situation, Nasheed remains cool, pragmatic and flexible, willing to compromise and try again another day. When all hope fades for any kind of written accord to be signed, Nasheed makes a stirring speech which salvages an agreement. While Copenhagen is judged by many as a failure, it marked the first time in history that China, India, and the United States agreed to reduce carbon emissions.

“In this age of political consultants and talking points, it is almost unheard of nowadays for filmmakers to get the astonishing degree of access that director Jon Shenk and his filmmaking team secured from Nasheed in The Island President. An award-winning cinematographer as well as a director, Shenk suffuses The Island President with the unearthly beauty of the Maldives. Seen from the sky, set against the haunting music of Radiohead, the coral islands seem unreal, more like glowing iridescent creatures than geographic areas. The parallel is apt, as the Maldives are as endangered as any species, and unless strong actions are taken, this magical country could become extinct.”

Bad Advice Wednesday: Give Yourself the Gift of a Writing Week

Doe Branch Ink is a writers’ retreat located on 50 acres nestled in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina. Just 30 miles north of Asheville in lovely Madison County — “The Jewel of the Blue Ridge” — the retreat takes its name from a spring fed stream that flows from high in Pisgah National Forest into the French Broad River, a protected National Scenic Waterway. This June, from the 17th to the 23rd, Bill Roorbach and David Gessner will be at Doe Branch.

Doe Branch Ink is a writers’ retreat located on 50 acres nestled in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina. Just 30 miles north of Asheville in lovely Madison County — “The Jewel of the Blue Ridge” — the retreat takes its name from a spring fed stream that flows from high in Pisgah National Forest into the French Broad River, a protected National Scenic Waterway. This June, from the 17th to the 23rd, Bill Roorbach and David Gessner will be at Doe Branch.

Recently Bill and I talked about the week.

Dave: The whole idea behind Doe Branch is to have a week where you put your writing first. A gift to yourself I guess. It’s a gift that sounds very appealing to me at the moment, caught in the swirl of schoolwork and blogging and fresh from filing taxes. The fact that you get to focus on your writing while living in a great setting, deep in the mountains, is a big part of it too.

Bill: The timing’s perfect—end of the school year, beginning of the summer. In fact, we’ll be celebrating solstice together, always a time of new beginnings.

Dave: In our blog we talk a lot about ways to protect your writing time. Usually that means a couple of hours a day, squeezed in between the pressures of daily life. This is different. Not little nibbles. A feast.

Bill: I still date a real turn in my life my writing and even my career to a week at a writer’s retreat. I’d been looking for a break from real life, and I certainly got that. But I got so much more, too, something I hadn’t expected. Suddenly, time  was all about contemplation instead of getting somewhere, doing something “important.” The days were capacious. I’d take a long morning’s walk and realize at the end that not only was I refreshed and full of ideas, but that it was still morning, that there were still hours of writing ahead. And then in the quiet I’d actually write, full of the feeling that nothing but writing and thinking would properly fill the space. And that’s what I did, feverishly starting and building stories in every open moment. In the quiet, away from the demands of real life, I found I could produced ten times more work in an hour, whole stories falling from my mind in mere afternoons. Best, when I was home I realized my priorities had shifted, that my ability to work with focus and concentration was much improved, that I wasn’t constantly getting up from my desk and rushing off to do this or that seemingly important task.

was all about contemplation instead of getting somewhere, doing something “important.” The days were capacious. I’d take a long morning’s walk and realize at the end that not only was I refreshed and full of ideas, but that it was still morning, that there were still hours of writing ahead. And then in the quiet I’d actually write, full of the feeling that nothing but writing and thinking would properly fill the space. And that’s what I did, feverishly starting and building stories in every open moment. In the quiet, away from the demands of real life, I found I could produced ten times more work in an hour, whole stories falling from my mind in mere afternoons. Best, when I was home I realized my priorities had shifted, that my ability to work with focus and concentration was much improved, that I wasn’t constantly getting up from my desk and rushing off to do this or that seemingly important task.

Dave: My thinking is that people should take as much time alone as they like. The way the week worked last year was great. I’m a morning person so I’d go for walks down into the hollow before we all gathered in the morning. I’d usually have some writing ideas of my own and would scribble them down in my journal. I even managed a couple of morning dips in the creek. By the time I got back, breakfast and coffee were ready, and soon after that, around nine, all of the writers would gather out on the porch. We did some writing exercises to warm up, read our work out loud, and I would talk for a bit about writing–that is, about goals, habits, craft, and whatever else seemed relevant to the work we were doing. I really tried to tailor the class to the goals of the people in it, so if someone was working on a novel I’d suggest books to read, for instance. Some people want more direction than others, and that’s fine, too. It’s their week.

Bill: I like to read from favorite books, find lessons there. And I’m hoping people will bring favorite passages to share, too. And I like to tailor exercises and assignments for those who want them, both fiction and nonfiction, even a little poetry. We’ll think hard about what participants need to bring their writing up to the needs of their various visions. And of course we’ll all be sharing our writing. There’s nothing like reading from fresh work and hearing what other writers and thinkers have to say about where you’re going rather than where you’ve been. I like aiming myself at future projects, getting a map in my head for what’s next.

Bill: I like to read from favorite books, find lessons there. And I’m hoping people will bring favorite passages to share, too. And I like to tailor exercises and assignments for those who want them, both fiction and nonfiction, even a little poetry. We’ll think hard about what participants need to bring their writing up to the needs of their various visions. And of course we’ll all be sharing our writing. There’s nothing like reading from fresh work and hearing what other writers and thinkers have to say about where you’re going rather than where you’ve been. I like aiming myself at future projects, getting a map in my head for what’s next.

Dave: That’s right. And another thing I find is that a week like this is good for starting to think hard about the form, or more accurately the shape, of the project or projects you are working on. What exactly is this thing you are working on? I tend to think of writing in terms of books, not shorter pieces, and what I try to do is help students conceive of how this thing they’ve got can be shaped into a book.

Bill: We’ll also have time to talk with each participant individually, both informally (at meals and on walks) and more seriously, over coffee in a quiet corner, trying to sort out challenges, move each of us toward the next positive step.

Dave: Ya, that’s kind of how it worked last year. We would meet in the morning until about noon, though during that more formal time people would also wander off to some beautiful corner of the property while they did exercises. When we were done we got served this amazing lunch that is catered by a local restaurant. The afternoon is generally a more solitary time, everyone off working on their writing. Until we get back together for cocktail hour of course. Then, drink in hand, the talk usually returns to writing.

Bill: The way I imagine it is this will not just be a time of camaraderie, but the time we come together to share this great vision of ours. And it’s where we’re all equals, all with something to offer, something to add, something to give. Some laughter doesn’t hurt at the end of the day. You’re an early-to-bed guy, but after dinner and after some talk around the fire , I’m more likely to be in my room writing till all hours.

Dave: On the other hand, people can just hole up at the end of the day if they like and keep writing. There are only a few formal planned activities. I went for long bikes rides and one day we all went river rafting. Also one night my eight year old daughter took on the local clog dancing champion at a restaurant in a nearby town. But that’s another story.

Dave: On the other hand, people can just hole up at the end of the day if they like and keep writing. There are only a few formal planned activities. I went for long bikes rides and one day we all went river rafting. Also one night my eight year old daughter took on the local clog dancing champion at a restaurant in a nearby town. But that’s another story.

To find out more about joining us at Doe Branch please click here.

April 17, 2012

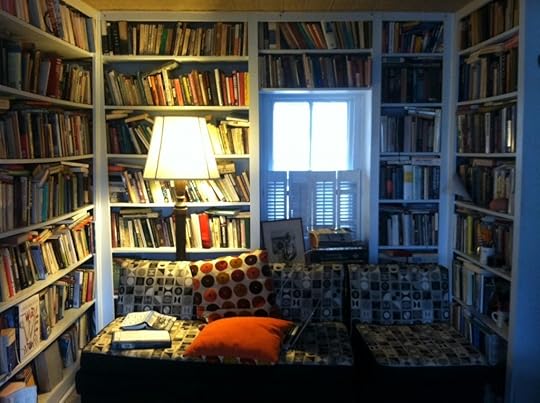

My Kindle Nook

Lifetime supply

A year ago I wrote here about my big push to organize and clean out my library, such as it was. And is. You can see the results above–the main bookcase is jammed, still, even with nearly 900 books carted off to various rescue shelters. I posted this photo on Facebook a while back and it seemed to strike a chord. On the right, I achieved a certain order. Poetry, biography, psychology (those are Juliet’s, primarily), gardening. On the left, chaos continues to reign: fiction. Some of these books have been with me from high school–40 years, that is–a few from childhood (Aesop’s fables in a box with my mother’s lovely handwriting). Large numbers are from college and the years after, which is odd, since those were peripatetic years and books incredibly cumbersome. Larger numbers were lost, of course, or given away. But never fear, I was a bibliomaniac, and collected books in great numbers, no matter I was broke. Do you remember all the crazy used bookstores around Union Square? To the right of the photo frame is our ancient and ugly and very efficient woodstove. In winter, one roosts and reads. Behind the camera is yours truly, then another bookshelf: literary nonfiction. And more shelves all over the house, most in my studio. Behind the camera also is a set of double doors and our deck, and out there and down the stairs and across the lawn a hammock, which I’ve just hung for a fresh season of books and naps. I do enough on screens these days–i want to smell the paper. And I want to throw the awful ones across the lawn. And read my notes, the marks of a younger man. In many I wrote the date of acquisition and place. And nearly all of my stories and essays started in the back blank pages of the books in my life.

What do you think? Books or e-books or both?

April 16, 2012

“A Prize I Won By Not Doing Something”

by David Gessner

This was last week’s post for my “Wild Life” blog at OnEarth magazine. Yesterday it was picked up by Andrew Sullivan on The Dish.

[image error]

With all due respect to resource depletion, global warming, and over-population, I have come to believe that the greatest environmental threat on the planet is our own minds. They are hungry little fuckers, these brains of ours. “We humans are an elsewhere,” wrote my friend Reg Saner, and boy are we ever. Walk across a college campus these days, as I do every day, and it’s a good bet you won’t make eye contact with a single one of the hundreds of students you pass. They are elsewhere, staring down into their machines, absorbed in urgent phone conversations, ears plugged and eyes glazed. “The hunger of the imagination,” Samuel Johnson called this insatiable desire for more, a desire that springs from a dissatisfaction with what is and from the hope that what comes next will fulfill us in ways it never has before.

We have turned that same insatiable hunger on our own land, swallowing, goring, fracking, drilling so that we can have more and so that we can fuel the vehicles and machines that transport us elsewhere. One of the reasons I find it hard to be too fully moralistic about this behavior is that I share it. In my own work –which is writing — I am always hungry, wanting more and better, and I recognize in my own ambition the same never-sated animal that I see in others. Long ago, I sent a letter to a neighbor on Cape Cod who had built a monstrous trophy house. I wrote: “You’re obviously an ambitious man and in that we are alike. While your workers hammer away up on the hill, I hammer away at my keyboard. Like you, I dream of creating something big, something great, and like you, I sometimes feel that my passion for this controls me, and not me it.” So you see, I am not writing about hunger as an outsider, not Spock looking on puzzled at a world full of Kirks.

And yet that does not mean that I believe that this gets me, or us, off the hook, that we can let our inner Kirks run wild and shoot phasers in the air and make out with every Nurse Chapel they run across. The next sentences in my letter to my neighbor were these: “But we are more in control than we admit, than it’s fashionable to say these days. I don’t suggest the laughable premise that we are rational creatures, or that reason controls our lives. What I do suggest is that our imaginations can be nudged, and work best if nudged earthward.”

Let me give you a small example of what I mean, an example that, not incidentally, ties in nicely with our hunger metaphor. Like my neighbor of old, I like to build, and a year ago I built a writing shack down on the edge of my backyard near the tidal marsh. I liked the way the shack connected me to the marsh and the creek and therefore the ocean and my old coastal home in the north. And I liked, or at least claimed to like, the modesty of the place, its ramshackle look and its basic admission of impermanence, an 8-by-8-foot plywood structure with a screen door for a window, the whole place ready to be wiped out by the next hurricane. It was a perfect spot to collapse after a long day, to birdwatch and drink a beer and do nothing. Except of course for our old friend, the real serpent in the garden: the hungry mind. I soon set to colonizing the space, to building a desk, stocking it with writing pads, taping outlines of my next book to the plywood walls. What I had was nice, but I wanted more.

And then, to my own surprise, I stopped myself. It was a small miracle of restraint. I decided I didn’t want to turn the shack into another study, a mere workplace like the one I already have in the house. I ripped out the desk. I resolved that, as best I could, I would check ambition at the door when I entered the shack. I could scribble down notes, read a little, sure, but there would be no plans and no machines, at least for the short time I spent there each day. Then one day, when a friend and I were sipping beers and watching the sunset from the shack, the friend pointed up at the gap between the top of the door and the roof.

“You better screen that in soon,” he said. “Or the bugs will be terrible.”

I nodded and agreed, but I never did fix it. Consciously, not lazily. I decided this was one time I wasn’t going to give in to the constant need for “improvements.” I decided that, just this once, I didn’t need more or better.

Almost a year has passed since that conversation, and three weeks ago the world rewarded me for my decision not to improve. Two Carolina wrens, beautiful little birds that hop and strut about like field marshals as they dip and lift their cocked tails, decided to take advantage of the opening above the door. They set to building a nest right over the screen window. You can see it in this picture, resting against the stick my daughter found on one of our walks.

[image error]

That would have been enough of a reward, but as it turned out, the world was just beginning to repay me. The wrens flew freely in and out to the nest, ignoring me though I was only four feet away. Then one day a couple of weeks ago I peeked into the nest and saw five eggs smaller than jelly beans. A couple of days later, I noticed that the female wren kept flying to the top of the door, but then, instead of flying to the nest as she usually did, she would fly back out, fussing in a nearby tree branch and on my roof.Something was different. I peeked into the nest and there they were: not birds exactly, but tiny living mouths. The four newborns were all maw. If Samuel Johnson had wanted a visual representation of his idea, here it was. Raw hunger.

My life feels better, more intense and elevated, having this new family around. Over the last two weeks the wrens and I have co-existed, though, feeling it was only good manners, I have spent less time in the shack, and each night I place the plywood cover over the screen window to keep the wind and rain out. When I do take a seat these days I witness the non-stop parade of feeding, performed by both the male and female, and I take notes in my journal of the type of insect or worm they have brought as an offering. The few minutes immediately after the feedings are the only time, outside of sleep, that the tiny birds stop pleading with their squeeze-toy squeaks and stop lifting their gaping mouths.

I won’t push my metaphor too hard. No doubt you get the point. Scientists might have a complex way of describing how the human brain operates, but I say it operates a whole lot like that nest full of birds. For my part, I am not ready to retire like a Zen monk to my shack. I am still hungry for things. A Pulitzer Prize would be nice, for instance, and after that maybe a Nobel. But right now I am enjoying a different sort of prize, and I can’t help but think this is a prize I’ve won by not doing something. And I’m encouraged by the fact that my mind is not in fact a nest of newborn birds, but a complex thing that can, every now and then, be controlled by something other than hunger.

It’s a small victory, I understand. But for the moment, it’s nice not to be elsewhere

April 12, 2012

One on One: Larry Bird vs. John D'Agata

When I was young a lot of my heroes were writers. But not all of them. One was 6'11″ and from French Lick.

Larry's great strength as a speaker was his directness ("Mosses does eat shit," being one of his witticisms. See the Churchill Wit.)

Larry's great strength as a speaker was his directness ("Mosses does eat shit," being one of his witticisms. See the Churchill Wit.)

And in today's New York Times he has something direct to say that speaks worlds to the D'Agata/truth in nonfiction brouhaha.

About the play Magic/Bird which just opened on Broadway and on which he consulted, he says:

"My main thing is to get it right. Don't say my mother said this when she didn't."

Magic, of course, takes the softer side: "We just wanted to capture our voice and make sure that, yes, it was an intense and tough rivalry, yet still, I've got this personality and Larry's this subdued cat."

Sounds a whole lot like "the emotional truth."

Larry Joe will have none of it: "You wrote that Red said 'S.O.B.' but he never swore. " And on insisting that the writers change the alcohol that Red was drinking to a Shasta: "I don't ever remember Red drinking."

No nonsense. The Larry Bird approach to nonfiction.

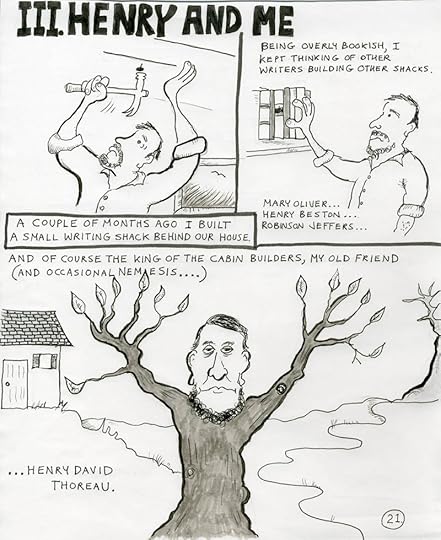

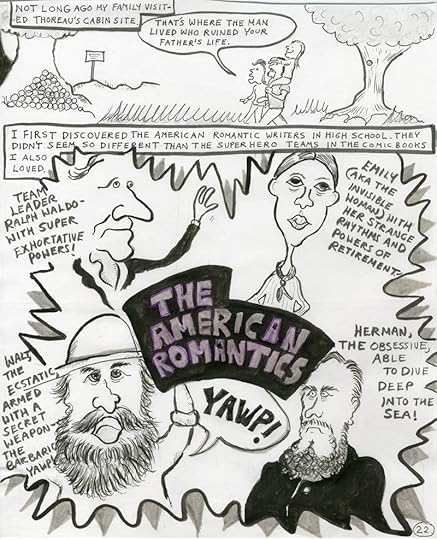

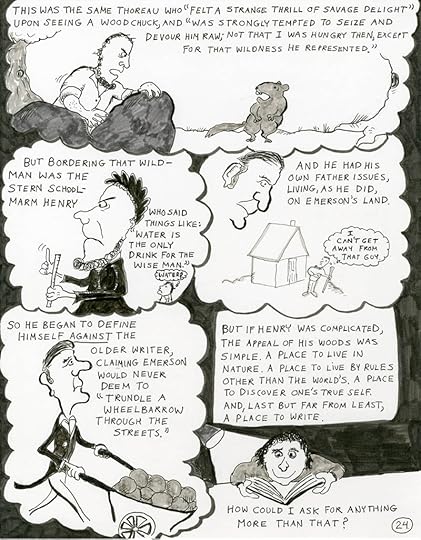

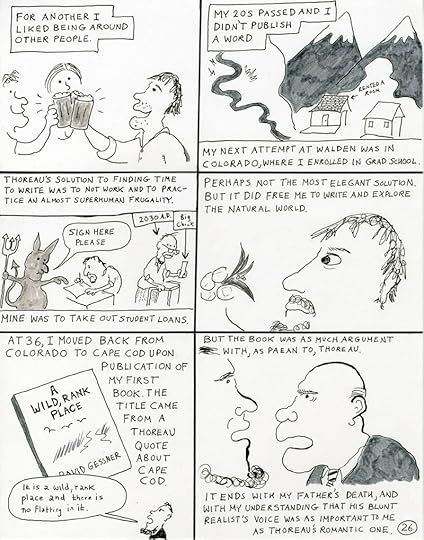

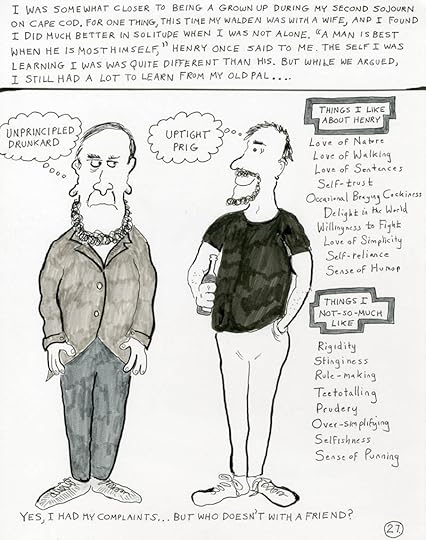

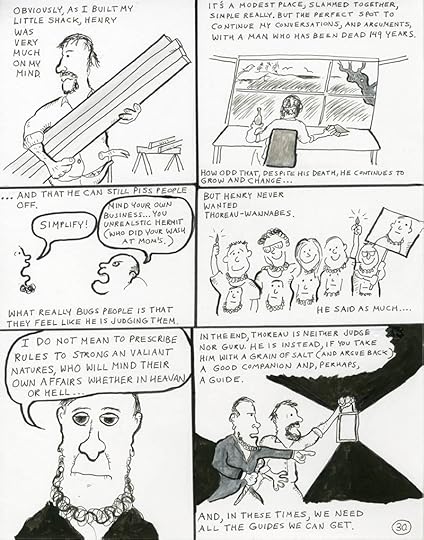

Henry and Me (In 3-D and High Def): A Cartoon Essay

We have been getting a lot more eyes on these pages lately, which seems a perfect excuse to recycle something old as if it's new (which Thoreau, the thrifty bugger, would have approved of). Anyway here, in a slightly different format, is my cartoon take on my complex relationship with Henry David…….

April 11, 2012

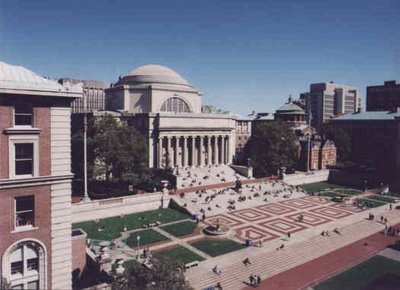

Bad Advice Wednesday: Decision Time, MFA

My Alma Mater, Graduate, at least

I remember waking in the middle of the night, mid-April 1986, wondering where my life was going to go. I'd applied to five MFA programs all around the country, no great logic in my choices (which were strongly geographical, but one) and swung between total confidence and total despair. I was 33 and the idea was to change my life. The letters came in one-by-one. Okay, Montana! I'm in. I'm going. That would be wonderful. I knew Montana well. Or, holy shit, Arizona, which came next. Okay, definitely Arizona, though it was known as a very academic department and I'd have to pass a French test. I couldn't have told you who taught at either place, had only set foot on the Arizona campus visiting friends in college. Cactus, though, I love cactuses. Both schools had offered fellowships, that was cool, and it hadn't occurred to me that money might be a factor. Then Johns Hopkins, wow. But Baltimore? The Columbia acceptance came late and my vision shifted. Hadn't I meant to get out of the city? But it was Columbia, Columbia University in the City of New York, where I already lived! Iowa wait-listed me, no sense of when they might let me know. And then, the day I committed to Columbia, the letter came from Iowa saying I'd been accepted there, too. I still wonder what that path would have been like. Or Arizona, or Montana. I picked Columbia because, well, because it was Ivy League. I'd never visited, even though it was just uptown, and never set foot on the campus till my first day of classes. Because I was terrified. All of it close to accidental. But for me, Columbia turned out to be great. I loved every minute of it. I taught, I played softball in Riverside Park. I had a free ride. That wasn't true for everyone there. In fact, Columbia is one of the most expensive rides around.

So today's advice goes out to those waiting for letters or those trying to decide between acceptances or those with no choices left.

Total failure: You waited and waited and now the letters are in and you've gotten in nowhere. Nothing. What? It's possible that this is because you really really don't belong in an MFA program. But it also might reflect mistakes made early on. I've had students who only applied to one program. Because, well, that's where they wanted to go, little sense that they'd be up against hundreds of other talented young writers. I've had other students, no better or worse prospects than their peers, who applied to ten schools and came up empty. The first instance is hubris, of course, and dumb. The second, honestly, is just bad luck. In both instances, the advice is: try again next year. It almost always works. Another year of writing practice, a better portfolio, better letters, and perhaps most important, a different committee on the other end. And perhaps a wiser slate of schools, some of the old ones, but a passel of new ones, too. And make contact with the people who run the places, with students, with faculty. Have someone on your team.

Partial failure: I had a really wonderful student who had one first pick, one middle pick, and one back-up. The first pick was Iowa, a very deep pool of applicants. The second pick was one of the other big land-grant schools in the Midwest. And she didn't get into either. Unfortunately, the back up was, well, I'll disguise it, but not much: The backup was Northwest Eastern Kansas State, let's say, and the program (this is real) was a masters in Agricultural Communications. She was leaning toward going for it. I said, that is not an MFA. She said, But at least it's writing. I said, are you interested in farming? She made a face. Advice was to try again the next year, and pick a bigger and more tailored slate of schools. She waited, and the next year got into the middle school, attended, and now writes.

Hedged bets: Oh, this is a popular one. Kid applies to three MFA programs and two law schools. Theory being that if he doesn't get into an MFA program first time around, he can always be a lawyer? Folks, there is a terrible glut of young lawyers out there. The top picks for jobs are those who went into it because law was their first love and first talent. Okay? Your parents great wishes be damned. Law school is not a back up. Because, this is what happens–kid gets into one of the law schools and one of the MFA programs. Parents lean heavily: law. My advice? Go to the fucking MFA program, enjoy two or three years of writing and being around people who write. Even with a partial fellowship you're better off than law students, who seldom get money, and seldom get to T.A. And hey, you can always do law school later.

Partial success. I love/hate these go-getter students who have sent you the forms for 17 schools, an afternoon of work for the weary prof at recommendation time. And now in spring comes the rebound: 12 acceptances. Not the top pick. Not the second pick, but lots and lots of others. The fellowships are various. The geography is wildly diverse. The programs are ranked all over the map. How to decide?

And then there's poor partial success: your bottom three picks have accepted you. Try again next year? I'd say yes, but only after you've given those schools that accepted you now a very close look.

Total success. This can be harder than it looks. You got into all your top picks, congratulations. How do you decide among them? Best if you can get the choices down to two or three leading contenders, and then study them closely in the time you've been allowed.

An MFA program is only going to be great if it's a good match for you. So, do some matching. I wouldn't go on reputation, at least not entirely. Rankings can be meaningless. A great fellowship at a lower-tier school can be worth more than any amount of rank. And your one life-changing great teacher can be hiding anywhere, at any school.

Geography's another factor. Do you really want to live in corn country for three years? Or in the broken heart of some minor city? Some people really don't care. If you do care: Don't go live somewhere you'd rather not. If you want to be in the mountains and have an offer, go be in the mountains, even though the money isn't as good, or the ranking lower. And consider the travel. One student realized she wouldn't be able to get back east very often–too expensive–and made a decision based on that. Another liked the idea of being stranded very much, and went for the school farthest away. Another saw an opportunity to get rid of her boyfriend, chose one of the lesser fellowships she'd been offered, and pretty much disappeared into the Pacific Northwest.

In all cases, if you don't have an obvious pick, and if practical, the best course of action is to go visit your top two or three choices from what you've been offered. If you only have one choice, go visit, too. If you hate it, don't go. Apply next year. If you can't visit, definitely call, ask to speak to a student in the program, a professor, the director. Most will be happy to talk. Find out who's going to be teaching for the next couple of years. Some schools have permanent faculties and seldom bring in guests: good–you know who you'll be working with. Have a look at their web pages, read a little (or a lot) of their work. Don't depend on their fame. Some famous writers are great teachers, others not so much. This is something conversations with students can help you parse. Some little-known writers are brilliant teachers, too. And then there's course load: Some famous teachers only teach one class a year, or even every two years. Will they be available to you? And all teachers have sabbatical years, leave years, retirements. Ask.

Other programs have a small core faculty and a constant turnover of visitors. This can be truly wonderful, if you are there for a good run. It can be terrible, too, as visitors, naturally, don't always have the attachment to the program and its students that core faculty might have. The big question is: who's coming in the next couple of years? How will they fit with you?

Money. Crucial. And a tough one. Is a free ride at a lesser program better than going into serious debt? Or having to work while everyone else is writing and studying? Those fellowships should weigh very heavily on your decision, especially if you don't have family or savings behind you. T.A. money not might sound like much, but it's usually adequate to scrape by on. The T.A. puts you into the school culture, trains you as a teacher, gives you a broader reach of colleagues. What are rents like at each program's location? And where are you going to live? Again, a visit tells you more than any other method. A great fellowship is a great temptation. But it's not an auction, with your choice going to the highest bidder. Weigh all the factors, and don't let a couple of thousand dollars either way sway you when other stuff might matter more. $20,000 difference? Okay, sway. You can live with an ugly campus if it means you won't be paying off student debt the rest of your life.

Results are another factor, more difficult to suss out. What's become of the graduates of the programs that have accepted you? Are a lot of them writing, publishing, making their way? Or are most of them in law school?

Best of luck. And tell us your stories. I'm happy to offer specific advice, if your query comes in this forum.

[And have you liked Bill and Dave's on Facebook today?]

@billroorbach on Twitter

April 10, 2012

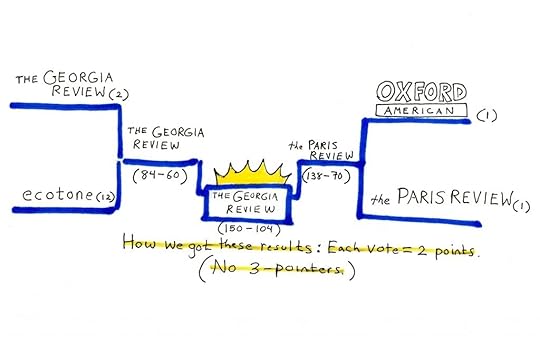

The Georgia Review Wins It All!

Despite a furious late rally by The Paris Review, The Georgia Review holds on for a statement victory:

Congrats TGR. Bill and Dave will buy you a beer next time we see you. Or at least Dave will.

April 9, 2012

Emma, by Jane Austen, Poolside, With Crocodiles

Books in My Suitcase

In college I often was sad for my future self. For one thing, I was sure I wouldn't have any fun on the millennial new year. I'd be 47 and dull and would have forgotten how to party, if still alive. But I was still alive back then in 2000, and still knew how to party. And still now, too, actually, even further into the Jetson era. Callow college fellows don't know about the stamina of late middle age.

Another thing I was sad about was that I would have read all the great books by the time I was 30, and then what? So I embarked on a plan, one I kept up for many years. Greedily, I read all but one of the books of all the reputedly great authors, and saved that one for later decades. (I even saved Dickens entirely). Which is why Emma has been on my shelf wherever I've moved these last nearly forty years, unread. So last month, on the way out the door to Costa Rica, my daughter having nipped Great Expectations, I tossed Emma in my suitcase–something to read along with Birds of Costa Rica, which is more like the Bible (and to which I'll return, in a post very soon). (I also brought along a library book: Tropical Rainforests, and it proved to be excellent. So more about that, as well.)

But Emma. It's a later book of Miss Austen's (as Lionel Trilling liked to call her), the last she saw fully into completion. And when in the second week of our adventure I finished Tropical Rainforests, and when I'd finished the days accounting of birds, I drew Emma out of the front pocket in my suitcase, brought it to the pool at our hotel in Manuel Antonio. And under an umbrella in the satisfying heat I began to read. First line, not so famous as that of Pride and Predjudice, but better: "Emma Woodhouse, handsome, clever, and rich, with a comfortable home and happy disposition, seemed to unite some of the best blessing of existence; and had lived nearly twenty-one years in the world with very little to vex her."

Already I was happy I'd saved this one out. Clearly Emma, the character, was about to be vexed. And vexed, she turns out to be much more complicated than any earlier Austen heroine. The book is never as funny as, say, Pride and Predjudice. Emma is earnest, nearly. She's a good person, but too insistent on that point, and very much too hard on others, nearly her downfall. She's also a busybody. She lives with her father, and for his sake, plans never to marry. Which means, of course, that she must.

In order, betimes, to forestall frustration, she engages in matchmaking, and causes no end of trouble, which she comes to regret, offering apologies. It's fun to watch her grow.

But I can hardly say what draws me through these pages so hungrily. A man in hiking boots and a dirty t-shirt, rancid shorts, rushing in from a rainforest adventure (crocodiles, scorpions, strangler figs, howler monkeys galore, the most bustling ecology in the world) to see what will happen when Emma's friend Harriet finds out that Emma has been quite wrong about a certain not very gentlemanly gentleman's being in love. Talk about bad advice!

Emma is a thinker. Her mind is a war zone. Nothing is black and white, though she likes to start with strict oppositions. Her goal is intelligent love, developed through reason, through the application of character.

Austen leaves a number of suitable men littered about the plot, but one by one they are married off. Emma's declaration that she will never marry is the engine. It's like a murder mystery, one suspect eliminated at a time. Emma, despite her fussiness, is so human (full of demons she can't entirely repress: jealousy, cattiness, hunger, boredom, a touch of wildness) that we care about her deeply, and cannot abide her wish for a life of duty. I rooted for one gentleman, then the next, found my hopes dashed when their character flaws came exposed. I laughed in the face of Mister Elwood, who dared propose. To my Emma! Fool! Just not suitable.

Sex is buried deeply under everything, the only overt mention being something about the saffron robes of Hymen being donned on one's wedding night, and a certain amount of perspiration on hot days. But then, ah, late in the book, the mere touch of the right gentleman's hand on dear Emma's arm? It might be the hottest scene in literature.

Alas, never was there a point in this life at which I'd have been a suitable match for Emma. The only respectable thing I ever did was save her story for my older self. And I must thank my younger–I enjoyed it very much, young man. And just look at all the books you bought me. Far more than a man of my subtly advancing years will ever be able to read.

Spend a Week Writing in Vermont at Wildbranch (as close as we get to an ad)

MY CLASS LAST TIME AT WILDBRANCH!

Come join us! Last time it was a perfect combination of intense writing, great camaraderie, and a beautiful place.

In the week we are there I will take my class through the process of drafting two essays, one a braided essay that weaves three topics, and the other an essay with a focus on place.

Here's the link. Here's the info:

The Wildbranch Writing Workshop is the country's foremost writing workshop for people interested in honing their ability to write honestly and powerfully about the natural world. Join Christopher Cokinos, David Gessner, Ginger Strand, and members of the Orion editorial staff for a week of writing and conversation in the rolling hills of Vermont's Northeast Kingdom. Application deadline April 12, 2012.

Two editors-in-residence from Orion magazine offer participants the option of a one-on-one critique of a piece of their writing. A limited number of manuscripts will be accepted for review on a first-come first-served basis and a 4,000-word limit applies. Those wishing to take advantage of this opportunity are asked to submit their work to the workshop director by June 1.