David Gessner's Blog, page 87

May 2, 2012

Bad Advice Wednesday: Make Like Shakespeare, or at Least Spalding Gray

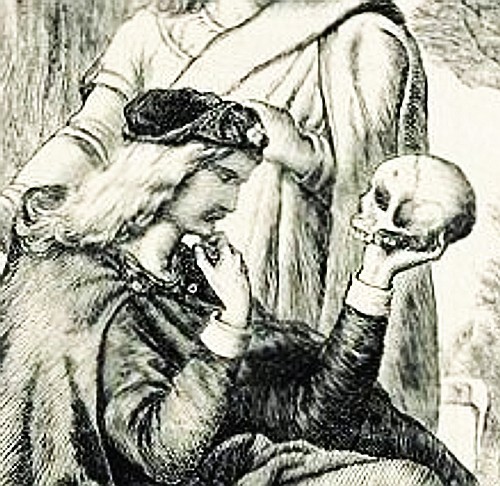

Alas, poor Dave! I knew him, Horatio.

.

Write a monologue.

.

Yes, that’s it. Today’s bad advice is to write a monologue. This is not just for writers, but for everyone. Though if you’re a writer, it’s a magical exercise. A monologue is one character (or even just a regular person) speaking directly to an audience. It’s different from a soliloquy, which is a character speaking to himself, audience be damned, though they’re listening in. It’s how playwrights used to get a character’s thoughts out to the world (filmmakers use flashbacks). A dramatic monologue? That’s a character speaking to someone else who’s usually sitting or standing uncomfortably nearby onstage. An apostrophe is a kind of dramatic monologue, but spoken to someone who’s not there, usually dead. An aside is spoken to an audience, out of earshot, so to speak, from other characters. I used to love George Burns’s asides to the camera on the Burns and Allen TV show, many years gone. An interior dialogue is a nice way to say it: talking to yourself. And then there’s the narrative monologue, telling a story. This is the stuff of stand-up comedy on the one hand, the greatness of Spalding Gray on the other.

Why, you may ask, should you write a monologue? Oh, go ahead, resist. I have no investment in your becoming a better writer, a better person, a better soul, almost a saint. Why, if it were up to me, only I would be allowed to write monologues. Because they are that cool.

So perhaps this is a soliloquy. But if anyone out there is listening, well, now, that’s dramatic, right. (I wake this morning with my belly arumble, my night having been filled with all things undone, or things done poorly, my day stretched too short before me, another night ahead!)

The exercise is as follows, adjusted for the various arts:

Essayist: You are already engaged in monologue, let’s face it. But if it’s a soliloquy, try aiming it outward—think of that one person sitting awkwardly onstage with you as you speak: who would it be? And for more drama, make it an apostrophe: to whom do you wish you could speak your piece without interruption? Well, do so. And be sure to stand up from your desk and actually say your essay, every word.

Memoirist: You, too. Aim that voice outward. But more than that, use monologue to get a handle on what your work is really about. Your bowling career, sure, but what’s the big picture? I mean, what’s it all about, being a bowler but also a human alive in the 21st century, or any century, come to think of it? The monologue gives you a chance and rather forces you to say what the greater piece is doing or should be doing, gives you a chance to get to the aboutness of your pages. Don’t tell stories in this monologue–that’s for the memoir itself. In this monologue, explain what your stories mean. Explain yourself. Another magical thing for the memoirist to do is to write monologues for all those friends and family in your piece. Not to use, because of course that wouldn’t be right, but to learn from–let them speak for themselves–and to hear voices. This is helpful for those who are dead or uncooperative, but also for those you can later phone or visit: You’re going to listen very carefully, now that you’ve spoken for them: what did you get right? What did you get wrong?

Juggler: Always with the banter, aren’t you. Try this: Make yourself a character, and tell the audience about yourself, all with pins and flames in the air, also a couple of oranges.

Novelist: Find every single character in your book and write a monologue for each. Not necessarily for the book, but to really hear who each person is, and what they’re thinking about. You’ll have a rounder, smarter, more vivid cast. And each character down to the lowliest passerby will have a voice their own. Stand your character’s mother up there, and let her go. It might surprise you (and your character) to realize that she isn’t actually thinking about the character’s plight much at all, but about her hairdresser’s affair with that physicist from the university, the man who gave a talk on prions and got Mom interested in going back to school, which, secretly, she’s applied for: Harvard.

Short Story writer: with fewer characters in tow and likely a shorter time frame, it pays to know what everyone’s thinking, down to the details. And the monologues you write now will improve the dialogue you write later: each character, her own problems, her own focus, her own voice.

Poets: You are already doing this, in one form or another. Discern which form. And then try the others. And, as for all your writers, read the stuff out loud and aimed at a person. Ideal if you can get that actual person to sit there while you do it.

Teachers (that’s all of us): This is a really great exercise for classes, students of all ages. You get the group to write monologues at home, or in class, and then–this is important–they perform them. For younger writers, you can bring a stack of index cards in different colors. On blue, say, the kids write a name. On red, a profession. On yellow, a place. On orange, an era. On purple, a problem. On green, an object. You collect all the cards, shuffle them, and pass them around color by color. And then the kids retreat to the various corners of their underfunded library or school and write. An astronaut named Bumidji Collins whose wife just left him, 1995, the South Pole. He’s got an electric guitar. After a half hour or so, all these new inventions, people who never existed before the index cards, come back and declaim. It’s really, really wonderful stuff, with even young kids able to find real depth, often sorrow, almost always comedy.

For college kids, you just send them home with instructions to write a monologue by one of their minor characters, and again, elicit performances. I actually make them stand up and speak to someone else (to make it dramatic), and give notes on the acting, get them to try again, really act. Then go back and revise.

Later, lo and behold, you find snatches and whole speeches from the exercise in the mouths of characters in their stories.

And I use the technique myself, when I’m trying to understand a character. In the new book, I’ve got a bad guy who’s just really bad and I was having trouble giving him motivations, trouble getting where all his manipulative, greedy, violent impulses came from. He surprised me by talking about money. That’s what he talked about. I hadn’t planned it. He talked in his monologue about money like the rest of us might talk about sex or food or love. And it really helped as I went forward with his scenes, a guy sizing up pockets as he went about his day.

A young woman I had written in a short story–minor character, love interest of the narrator–surprised me in monologue (aimed at her best friend, who never made an appearance in the story at all) by talking very passionately about him. And here he (and the story) had thought the relationship almost over, a disaster. So then I had her talk some more. He required too much coddling, too much reassurance. And he was too passive. His neediness excited her resistance, his passivity made her listless, though she loved him. And in her monologue she remembered the bed of much better lover than my protagonist, remembered an earlier, angrier boyfriend, found protagonist altogether much more wonderful, just frustrating, even a little impotent. And at the end of all this the friend said, “Buy him flowers.” Which I thought at first was a throwaway, a joke, something my subconscious mind pulled for laughs. I cut it.

But then in an advanced draft of the story, I surprised myself by trying a new opening: the young woman given our protagonist flowers, a huge bouquet she’s picked from the fields. So, okay, now that was how the story started. She’s overcome her aversion to coddling anybody and brought him flowers, kind of feminizing, of course, the opposite of what some might think he needs, but, no: the gesture changes him in some ineffable way, and the change powers the story (it had lacked an engine), a story that’s not about their relationship at all.

In life, you can use this exercise to parse problems. Write monologues for the people who are bugging you, for example. Or write your own monologue, holding their skulls in your hands.

(I’ll talk about Spalding Gray at length in a future post–he’s the tragic hero of the narrative monologue.)

(And please, Like Bill and Dave’s–that button up there in the upper right hand corner? Like? It produces endorphins in your brain and makes you feel as if you were in love–go ahead, try it! And speaking of endorphins, follow me on Twitter: @billroorbach)

May 1, 2012

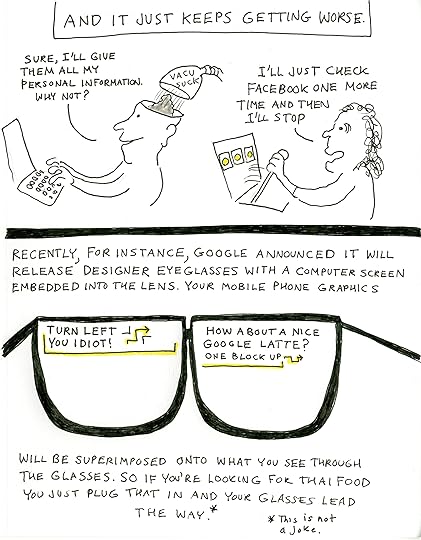

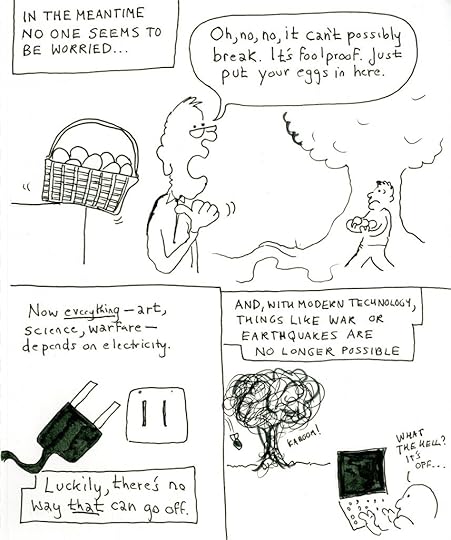

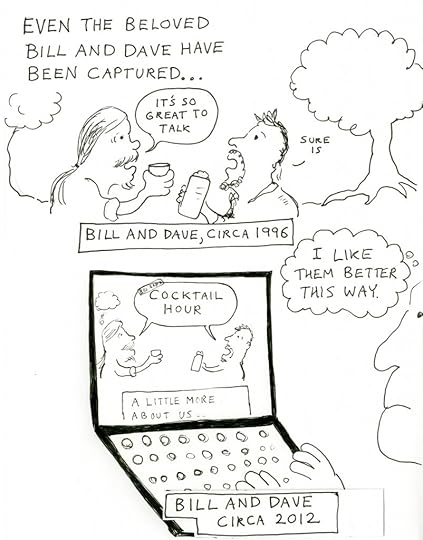

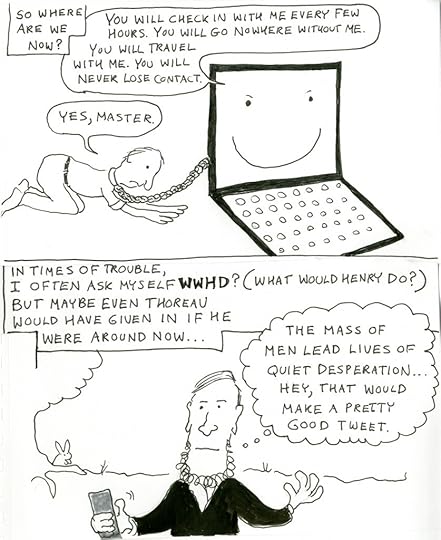

Give Up All Hope: The Machines Have Won, and You Have Become Your Computer’s Slave

April 28, 2012

Getting Outside Saturday: Spring Goodies

It's spring in Maine, and here come the ramps.

.

Favorite things. A sunny spring morning, a walk in the woods, a few things to eat (nothing the settlers wouldn’t have had, and much that the Abenaki before them would have had, too). I bring a trowel, tease a handful of ramps from the rich soil near a basswood tree –these wild leeks smell sweetly of mild garlic, milder onion, leeks, sure, something of a shallot. Home, you chop them–the bulbs minced fine-ish, the leaves more course. A little butter in the crepe pan–no a lot butter, and throw the bulb bits in–quickly, they caramelize. The leaves go in next, light and full. Very quickly in the heat and butter they go limp, cooking down the way, say, spinach does–a handful shrinks to a big bite. You could eat them now–they’re that delicate, and very fragrant, a treat. But I’ve got eggs from the hen-house and the yolks are rich from insect feeding (more spring gifts) and I beat three and drop them in the pan with salt and in seconds my ramp omelette is ready, killer. For dinner, ramps braised in wine and butter, maybe with pasta and a salad of winter lettuce and odd mustards from the coldframe, also trout lily leaves (everywhere in the woods right now) and ostrich-fern fiddleheads cooked soft in butter then cooled–almost like asparagus, of which I’ve got exactly one spear from the edge of the garden, harbinger of the weeks to come.

.

Trout lily--leaves leaping spotted from the forest floor, diving back in only weeks.

.

“

Fiddleheads of the ostrich fern, the kind you want to eat! (foto Leslie Steele)

April 26, 2012

The MFA Tournament: Help Crown the Best Writing School in the Country (Vote Early and Often)

What’s the best way to decide the top MFA creative writing program in the country? A tournament of course! Vote on our comments page!

By almost all accounts the current system of ranking MFA programs in creative writing is a crappy one. For starters the rankings of the schools are determined by applicants who have never seen the schools and never had the teachers. That’s right (believe it or not), the rankings depend on the choices of people who are applying to schools, and basing their choices on a variety of criteria, including the ranking system from the year before. Let me say that again so it is crystal clear: the folks who created the rankings didn’t make any attempt to survey those who have actually experienced the program. To which we say: Yikes!

“It’s analogous to asking people who are standing outside a restaurant studying the menu how they liked the food,” says novelist Leslie Epstein, who runs the Boston University Writing Program.

Poets &Writers, the magazine that publishes the rankings, replied:

“Why didn’t we survey MFA faculty and students about the quality of MFA programs? To continue the analogy Leslie Epstein used to describe our approach in the press release, that would be like asking diners who only frequent their favorite restaurant to assess the quality of all restaurants.”

Okay, love both restaurant analogies, but can’t help but believe that the first is a little better, that is that talking to people who have tasted the food should factor in. Right?

So are rankings useless? Hardly! They’re fun! But we here at Bill and Dave’s believe that if you are going to employ a flawed system, it might as well be fully flawed. And so we are announcing our first annual Tournament of MFA Programs. Why not crown the best in the old fashioned way? Let them fight it out.

The Poets & Writers system, created by the great Lawyer-Poet Seth Abramson, is explained in a pithy 80 page document that you can read (for pleasure) here. Our own methods are generally considered too complex for regular humans to understand, but if you want to try and comprehend them you can read Dr. Bill Roorbach’s Rationale of Methodology (printed below).

But the short version is this: We believe the fairest way to determine the best creative writing program is by counting how many votes they get here at Bill and Dave’s Cocktail Hour. What could be simpler? Whoever gets the most votes wins! When it’s all over, shiny prizes will given and cash too. But most important of all will be the glory of being crowned number 1 by Bill and Dave (in person at next year’s AWP in Boston).

Let the games begin!

How to play: simply cast a vote (only two per person please) for your school (and one other school if you like) in the comments page of this post. Next week we will report the results of the first round and move on to the next.

Rationale of Methodology by Dr. William Roorbach

To help us gain scientific accuracy, we ask a representative selection of respondents to name the best restaurant in the vicinity of the program you are voting for. If such respondents look like writers (cigarettes, darkly hooded eyes, paranoid glances) they are bought a sandwich. (See appendix 1289.) The best analogy really is airline food, which really isn’t bad in first class, or on Air France and Air India, and imagine the algorithms they have to use to get vegetarian meals to certain percentages of their passengers, none of whom were on the plane the night before the flight, and yet all of whom need to get somewhere. But back to algorithms, and the sound if not spelling of rhythm in every usage. (See table 456.) We do not weigh for cities we like, though cities we don’t like or think we might not like must be tested for water quality by our team of Navy Seals, which are actual seals. Does the city have a zoo? (See pages 45, 78, 695, 2356, and 12360.) And what is the proportion of pigeons to people? No, on second thought, best analogy would be Depends undergarments. Ask the user what he or she thinks of the garment before and after use. Honestly. Clean results demand a pristine undergarment. (Consult diagrams B19 through F78.) Comma usage, a must. Only votes cast by those who might be reasonably assumed to find dancing germane are taken perfectly seriously, though imperfect seriousness is a tool we are never afraid to apply. (See “The Turning Point”: it’s actually really good.) It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife. Simply put, objectivity obnubilates merely callipygian asseverance. Body types are not taken into account, really not. And besides, how important can money really be when most writers don’t have a lot of money. (See bar graph, pie chart, and flow panels.) Fellowships are all well and good, but it stinks of the 1950s lodge system, which we eschew. Elks and Odd Fellows indeed. That’s a point worth going back to: Elks and Odd Fellows indeed! Percentages are acquired by reference to a chart of percentages and this accounts for nearly 40% of our dependibility quotient, though the formula used may be baby formula. (Fully outlined in subsequent chapters.) What’s that you say? Faculty is weighed and those that weigh more than Bill are asked not to go to restaurants quite as often, though this is not an a priori observation but merely more of the rhythm method adopted above. Student satisfaction can have no place in this analysis, so only unsatisfied desires get full weight. (See addendum.) The hypotenuse is equal to the sideburns of the chair of the program squared indefinitely. And really, can’t we all wear better shoes? (See Zappos.com) When one program gets equal votes to another, both are docked till all programs have the same vote totals in which case a tie is declared and worn to three funerals in seven years, the only time I ever touch my black jacket, which is wool and quite hot in summer, a bad time to die. (Ibid.) Any vote accompanied by cash is weighted in direct proportion to the side orders it can buy. Programs in tropical areas get preference in winter. Formulas do not apply.

April 25, 2012

Bad Advice Wednesday All-Star Guest Post: Whistle While You Wait

.

To be a writer is to be a waiter, and I’m not talking about tables. Waiting. It can be the most excruciating part of the whole process. You spend years working on a book, pounding out a first draft, sweating over the revisions, doing everything you can to bleed your heart out onto the page. When you finally declare yourself done – or at least done enough to hand the manuscript over for a verdict — that’s when it begins. Even if your first reader is just a friend whose opinion you value, it can be brutal. One day ticks by, then two, then a week. Has she started reading yet? Was it so boring that she couldn’t get past the first page? Does she hate it so much that she needs time to finesse a diplomatic response?

Don’t worry. Eventually your friend will respond. She may have helpful suggestions for revision, or she may absolutely love it the way it is (the latter is more likely if the friend is not a writer herself). Either way, the TRULY brutal waiting is now getting closer, because the time to submit to professionals is nigh, and if you think your friend took a long time to read…

I’m sorry to be the one to tell you this. But if you haven’t yet published a book, there’s no predicting how long you’ll wait before hearing back from prospective agents. At Absolute Write Water Cooler, a site for writers, most threads regarding agents involve complaints about response time, in some cases more than a year, and in one case FIVE YEARS – by the time the agent replied positively to the query, the book had already been published. “Grow a thicker skin and move on,” advises this patient fellow. “Rejection (and being ignored) is part and parcel of the writer’s life.”

Of course these are extreme examples, and once you’re an author who already has an agent, your wait won’t be nearly as long. But you still can’t presume a speedy reply. Not only do agents have stacks of manuscripts on deck from aspiring and established clients, the nature of the business precludes scheduled reading time. Your agent may have every intention of reading your novel this week, when suddenly he finds out that a prospective client who submitted a five hundred page memoir is getting offers from three other agents. So your manuscript gets bumped off the top of the stack yet again (Of course it’s a metaphorical stack because your agent reads on a Kindle or Ipad). Meanwhile the hours and days and weeks are again ticking by, and the sense of confidence and love you had for your book is not only waning, but morphing into the sort of anxiety that begs for medication. Think this ends once an agent has read and loved the book? Prepare to refill your prescription, because now the submission process begins. I have a friend whose brilliant, gorgeous, and highly readable second novel (the first sold well and got great reviews) took two years to find a publisher.

So where does the bad advice come in? For one thing, you need a special ringtone for your agent to prevent your heart fluttering with wild hope every time the phone rings. Beyond that, you kind of have to accept the fact that once you’ve written the best book you possibly can, it’s out of your hands. You’re going to have to wait, possibly for a very long time. And so the only choice you really have is to start a new project.

I have heard writers say that their books are like their children. Perhaps I’m lucky not to feel this way. Whenever anyone asks me which of my books is my favorite, the answer is invariably the one I just finished, or the one I’m working on now. To me books are like romances, and you know the best way to get over one of those. The only way to stop pinning all your hopes and dreams on the book you just finished is to write another one. The incomparable Brad Watson once told me that when he’s working on a novel, ideas for other books are like sirens, calling to him from the rocks. But once that book is finished, you’re free to give your mind over to those siren songs. Everyone knows that a watched pot boils at precisely the same speed as an un-watched pot. The trick is in not exclusively waiting. The trick is in rejecting the timetable of the business, and creating your own timetable for doing the work you love, which is writing books.

Will that make the waiting easy? Will it stop you from diving for the phone, heart aflutter, when you finally do hear your agent’s ringtone? Probably not. But at an absolute minimum, whatever the fate of the book you just wrote: you’ll still have the book you’re writing

April 24, 2012

Is It Safe to Eat the Fish? And Other Questions Two Years After the Spill

by David Gessner and Bethany Kraft, deputy director of the Gulf Restoration Program at the Ocean Conservancy.

David Gessner: Last Friday was the two-year anniversary of the BP disaster. For many of us, the spill is spoken of in the past tense, but for those who live on the Gulf, it is not. What strikes you the most after two years?

Bethany Kraft: Looking back, there is one moment very early on in the summer of 2010 that really stands out to me as a harbinger of the chaos to come. It was late April and the government response was being mobilized in Alabama. I got on the phone with several officials who were in charge of coordinating the placement of the boom that would ostensibly protect our most environmentally sensitive areas from the onslaught of oil. My questions were simple: where had the boom been placed and where would it go in the coming days? The answer I got was both hilarious and terrifying: “We can’t tell you where the boom is or where it is going in because no one has given us a printer.”

We weren’t prepared for a disaster on the scale of the Deepwater Horizon — we didn’t know how to adequately protect our natural resources or our economies or our most vulnerable coastal communities. We didn’t know how a massive volume of oil would impact the Gulf ecosystem. We didn’t have the technology to respond to a deepwater drilling incident. We couldn’t even find a printer to make the maps to tell us where to put boom.

Two years out, I worry that the lessons we swore we would learn in those early months haven’t been given more than the most cursory consideration. I’m concerned that we still have so much to learn about the impacts of the disaster, and I fear that we aren’t any better prepared to address technological disasters than we were two years ago.

DG: When I was traveling along the coast during that unctuous summer of 2010, the scientists I talked to often said: “We’ll have to wait a couple of years until we even start to know anything.” Well, here it is, a couple of years later, and sure enough, we are starting to know some things. Over the last few weeks we’ve had reports about dying coral, sick and stranded dolphins, and low catches of shrimp and oysters.

BK: The images we saw of oiled wildlife in the summer of 2010 were just the tip of the iceberg. It takes time for scientists to understand how various species are affected, particularly if you are looking at impacts that may not show up for a generation or more, (like reproductive problems). We’re starting to see more oil-related studies crop up in the scientific literature, and so far the news is troubling. We know that birds, sea turtles, shrimp, finfish, and oysters were impacted, but now we are learning about damages caused to deepwater corals, killifish, zooplankton, and insects and spiders, just to name a few. And there is still much work to do to determine what those damages mean in the context of the Gulf ecosystem. For example, Gulf killifish play an important role in the food web. We know that these fish were exposed to BP oil in Louisiana marshes and as a result are growing up with damaged gills, but we don’t yet know what to predict in terms of how this may affect their reproduction or the Gulf food web. This work will continue for years.

The human impacts are just as bad and still ongoing. The BP disaster was just the latest in a string of challenges that face our coastal communities. Imagine a fisherman in Bayou La Batre who lost his house, boat, and livelihood after Hurricane Katrina and was just starting to get life back to normal — only to have the rug pulled out from under him again and lose all of his income for an extended period. One thing I’ve found fascinating is a study about the fabric of community by Steve Picou, a sociology professor at the University of South Alabama who studies the human impact of technological disasters that cause massive environmental contamination (see “Q&A: A Human Disaster,” Fall 2010). He said that natural disasters bring people together in a way that makes them stronger in the long run, but that technological disasters tend to do the opposite by breeding distrust in government and other institutions and reinforcing an “every man for himself” mentality. Our culture is still feeling the effect of this, and it’s very alarming.

DG: I live on the coast of North Carolina, and bottlenose dolphins are my neighbors. During my time in southern Louisiana I became friends with some filmmakers who worked for Jean-Michel Cousteau’s Ocean Futures Society. During the height of the spill they took me out into Barataria Bay on their boat. We watched dozens of dolphins dive in and out of the water, and then they swam right over to our boat, curious. I was struck by the fact that they were living in a stew of oil and dispersant.

BK: The recent news of the declining health of dolphin populations is very troubling. They are high on the food chain and in many ways act as important indicator species that tells us a lot about the health of the ecosystem. More than 600 cetaceans have stranded themselves on Gulf beaches since April 2010. Early results from 32 dolphins tested in Barataria Bay in Louisiana show that many of these dolphins are underweight, anemic, have low blood sugar, and/or have signs of liver and lung disease. About half have low levels of hormones that help in stress response, metabolism, and immune function. Many of those still alive are not expected to survive. For me, this is one of the most compelling reasons that restoration in the Gulf has to have a strong science and monitoring component — we need to continuously take the pulse of the Gulf ecosystem so we can address problems like declining health in our dolphin population. I like to think that I’ve stayed fairly focused and level-headed over the past two years, but listening to government scientists reel off this laundry list of dolphin impacts was very difficult for me. It’s not acceptable.

DG: I’ve been very critical of the media coverage of the spill, which, in my mind, went from all to nothing. As I’ve written in these pages, during the summer of 2010 close to 40 percent of all televised news coverage was about the spill. But then, as if embarrassed by this excess, the coverage all but disappeared. I have been particularly critical of the New York Times, which reported credibly on a rosy NOAA report in July 2010 that said the oil had all “evaporated” or been eaten by oil-eating microbes. They story ran under the headline “Oil in Gulf Poses Only Slight Risk, U.S. Report Says.”

Lots of scientists criticized the report, but the effect was: “This is over.” The capping of the well in September seemed to mark the end of the official coverage. There was a good piece in the Wall Street Journal last Friday, but even that piece had a “not as bad as we expected” angle. Which is understandable: it wasn’t the complete nightmare many of us envisioned at first. But I feel that our relief over this, over having “dodged a bullet,” blinds us to the less obvious impacts. One thing I’ve noticed in all the mainstream coverage is the fact that no one seems to mention the millions of gallons of the dispersant, Corexit, that were dumped into the water. In the Wall Street Journal piece, for instance, the only mention of dispersants is to say “chemical dispersants broke up crude both below the surface and on it, as did naturally occurring oil-eating microbes.” On the other hand, the story does conclude with this quote from the scientist Doug Inkley: “The oil spill is to the Gulf what smoking is to a human. You’re still able to function overall, but not nearly as well.”

BK: In some ways I understand the media’s desire to put a bookend on the whole saga and move on to the next crises, and I understand that people outside of the region may not see the disaster as relevant to their daily lives. But the story of the Gulf of Mexico is not simply the story of the Deepwater Horizon. And BP isn’t the only bad guy. The Gulf has been an incredibly prolific ecosystem, and until the last 100 or so years, we haven’t had to worry that it wouldn’t be able to give us everything we wanted. But it’s now clear that it’s no longer a given that the Gulf can absorb all of our requests for its bounty and remain unchanged.

The list of woes facing the region is long, and you’ve likely heard them all before: nutrient pollution, wetland loss, loss of barrier island protection, unsustainable fishing practices, and on and on. These challenges aren’t new, and they aren’t going away unless people in, say, Iowa realize they have a stake in improving the health of the Gulf of Mexico. What makes the story of the Gulf oil disaster so compelling (and frustrating) for me is that this is one case where the villain, BP, also has an opportunity to be the hero — not by choice, but as a result of the lawsuits and government fines that should result from the spill. For years we’ve said that what we on the Gulf are lacking is funding to restore our ecosystems. But now, through established legal processes that came about as a result of the Exxon Valdez spill, we can mitigate the damage caused by the oil disaster. And there is a second potential source of funds: fines levied against BP by state and federal agencies for violations of environmental statutes like the Clean Water Act and Marine Mammal Protection Act. Those could go a long way toward addressing long-term degradation in the region. We don’t yet know the total dollar amount BP will end up paying, but we do know we need legislation to move that money to the Gulf, and that the bill that would do it, known as the RESTORE Act, has not been passed by Congress.

If we expected the entire Gulf of Mexico to become a toxic gumbo of Louisiana sweet crude and dead animals after the rig explosion, then no, the media’s depiction of the “worst-case scenario” didn’t come to pass. But if we let another year go by without seizing the opportunity to address both oil impacts and long-term degradation, courtesy of BP’s pocketbook, then I will consider that a worse fate. It will mean we have learned nothing and that all of the sacrifices that have been forced upon us were in vain.

DG: One of the things that I think confuses people are the claims, prominent in the current batch of BP commercials, that Gulf seafood is safe to eat. Their commercials trumpet the fact that the seafood has been frequently tested and none of it has been found to be contaminated. When people hear this, they assume the Gulf is back. But testing for chemicals in seafood is not the same as testing for deformities and habitat degradation. What do you make of the testing? I know that traces of oil and dispersant have been found in some species. Given this, how can it be that the seafood is all considered OK to eat?

BK: There are no simple answers to this question. For instance, if a study were to show that a particular fish species experienced health impacts as a result of being exposed to oil, that doesn’t mean that a human would expect to have the same health impacts or that the seafood isn’t safe for human consumption. When talking about potential risk to humans, the answer depends on what particular type of seafood you are consuming, how much and how often you consume it, and whether you are considered a member of a vulnerable population, like a young child or a pregnant woman. This study from the Natural Resources Defense Council (which publishes OnEarth) claims that the FDA’s allowable limits of some oil-related contaminants were not sufficient to protect vulnerable populations, and that concerns me a great deal. Unfortunately, there is no single source of information on this issue, so we are left to make the best decisions we can with what we know. For me it boils down to the following:

Trusting what the science says is a better bet than trusting a slick PR campaign

Continued testing and monitoring is not just important for the seafood we consume, it’s important for the entire restoration process. Without an investment in science and long-term monitoring, we won’t be able to answer these questions with any degree of certainty.

I really like Gulf seafood, and I still eat it, though not as often as I did prior to 2010.

DG: For me the Gulf spill has had an almost metaphoric importance beyond the spill itself. It’s shown me how we think as a nation. How we get obsessively into something, then ignore it, and how we operate in panic mode, emergency mode. One thing most of us certainly don’t do is think like naturalists. A naturalist looks for connections, sometimes subtle, and notes effects that are often hard to trace back to their source. An example would be the hike we took with Bill Finch on Grand Bay in July of 2010. He pointed to the millions of periwinkles that were eating the marsh grass, and noted that the only thing that kept the periwinkles in check were the blue crabs, which were at that moment migrating back to the marsh over the oily ocean floor. Were the crab population to fall, the periwinkles would be blamed for destroying the marsh, but it is always more complicated than that. That’s the kind of subtler disaster that doesn’t make the news. It’s not as sexy as an oiled pelican, but that doesn’t make it less real. For instance, in Alaska, years after the Exxon Valdez disaster, the herring fishery collapsed. The thing with these sorts of troubles is that they are hard to trace back to their source.

BK: Ecosystems are complex. They function in ways that we don’t fully understand. As you said, connections aren’t always easy to make, even for scientists, and they certainly aren’t easy to describe in a sound bite. I think a lot about the best way to make these concepts relevant to regular citizens, because though they are complex, they affect us profoundly. Over time I’ve come to believe that there is one word that is critical to our understanding of how ecosystems work and how damaging one link in the chain can affect the very way we live. That word is why. I know we are capable of asking this critical question because we all learned it and wore it out by the time we were 3 years old. When confronted by something we don’t fully understand, all we have to do is ask why, then answer the question, then ask why again and again until we get to the very root of the issue. The fancy term for this is root cause analysis, and it is a powerful tool to understand how things are connected and what we can do to actually solve problems, rather than simply alleviate the most obvious symptoms.

To use your example above, let’s say that I go back to Grand Bay and notice that the marsh grass doesn’t cover as much ground as it did in 2010. Why? It’s being eaten down by periwinkles faster than the grass can grow and reproduce. Why? There are more periwinkles than in previous years. Why? They’re reproducing faster. Why? Their natural predator, the crab, is present in much lower numbers. Why … on and on you go. If you don’t ask this fundamental question, you may well stop before you get to the right answer. For instance, if I saw periwinkles proliferating and damaging the marsh grass and didn’t trace the cause back to its root, maybe I would say that the solution is to try to eradicate the periwinkle so the marsh could grow back, when really I should have kept going and gotten to the point where I decided to focus on bringing the crab population back up. It’s a different way of looking at the natural world, but I think it’s the only way to accomplish lasting and meaningful restoration in the Gulf.

Tracing ecosystem impacts back to their source is difficult, but it can be done. And there’s not a single one of us who isn’t capable of acting like a 3 year old, so I think we are up for the task.

April 23, 2012

The Hunger Games, Movie and Book. Is this for kids?

.

It’s been a long time since I read a book and saw the movie in the same day. Last time was “To Have and Have Not,” the Hemingway potboiler, not bad page for page, and I read it in an afternoon. The movie happened to be on TV that night, and I remember watching in my parents’ basement (I would have been home from college), really surprised: aside from the title and the names of the characters, it had nothing to do with the book. Turned out that William Faulkner (“Out of work and broke”) had re-written the screenplay under contract with Warner Bros, putting together what amounted to a parody of his rival’s work. Starring Bogart and Bacall.

.

My daughter is eleven and read The Hunger Games before either her mother or I had heard of it. Of course, the kid loved it, and downplayed the violence we’d begun hearing about. To me it sounded like an allegory for life in high school, which is in turn an allegory for corporate life, if not life itself: there are winners and losers. And I’m a proponent of the Bruno Bettelheim “Uses of Enchantment” idea that kids need fairy tales in all their grimness or Grimmness, witches, dead children, and all: the imaginative use of pretend horror to help deal with the real vicissitudes of life.

Jennifer Lawrence as Katniss

So Saturday night I sat down to read The Hunger Games, which if you don’t know is by Suzanne Collins, formerly a television writer, primarily for Nickelodeon, and aimed at the young adult market. By bedtime I was halfway through. It’s not a long book and has fewer words per page than books for grownups. More than that, though, it’s a massive page-turner—a plot that comes at you full speed, skating over a very simple, filmic structure. And the narrator, Katniss Everdeen, is very appealing, a strong voice, compassion, kindness, power, knowledge of the forbidden world outside the fences that surround her district, which is a mining district. She’s a great hero for all of us, but certainly for young women and girls. It’s told so briskly as to be schematic, but you still come to love and admire the heroine.

The basic story is that each district in a post-American, post-disaster country must hold a lottery and send two kids—one of each gender—to the hunger games, the ultimate reality show and release for an oppressed nation. 24 kids are chosen, put in an arena that looks like life—forests, ponds, rivers, etc.—and told that only one can come out alive. (I’ve been reading about a Japanese book and subsequent movie that share a similar plotline, Battle Royale, in which high school kids from the same school fight to the death.)

Anyway, I finished the book Sunday afternoon just moments before the sitter arrived, fun for Elysia, who loves to hang with college women. And I shot into town to meet Juliet. We’d planned a walk but it was raining and so to the movies, and The Hunger Games, which we’d been meaning to see. The question being: should Elysia be allowed to see it, as so many of her friends (quite a few of them older, but not a few younger) had already done?

And honestly, it’s a terrific movie. Jennifer Lawrence is perfectly cast as Katniss (though she’s 21 and looks it, not 16). For one thing, she’s unbelievably gorgeous, a shifting, unsettling beauty powered by her clear intelligence. But she can act, too, and the part requires a lot of subtlety. Woody Harrelsen’s in there,too, and does a great job. Most surprising is Lenny Kravitz, playing a stylist. He’s as beautiful as Jennifer Lawrence. Stanley Tucci plays the host of the games and he’s brilliant—cynical, sadistic, charming, the perfect dandified simulacrum of his character’s society and a good reason to cast great actors in small parts.

And the kids go at it. Most die. It’s no slasher pic, but it’s very intense and quite bloody at times. There’s a modicum of sex: chaste kisses. Let graphic leg wounds serve as representations of genitalia, since violence in our own so-called culture is fine where bonking is not. And let the mutual application of super-balms serve as sex. (The child of a friend of mine thought PG-13 stood for Pretty Gross: 13)

Thirteen, okay, maybe. But this is certainly no movie for an eleven year old. And though she’s campaigned hard for the right to see it as her peers have, she no longer wants to. Because we told her about the wounds. She doesn’t even like it when Daddy gets a cut. We told her about how sad, little Rue and the flowers. And we told how loud and how fast-paced and how really terrifying at times.

There’s nothing in the movie that isn’t in the book. But the movie is a step toward the real, whereas a kid’s imagination as she reads is a place of learning and safety. A kid reading can stop and think while she reads. She can process the imagery–which her own mind has produced from prose cues–for a minute or an hour or a day or a week. And then she can step back in.

And finally, there’s something about the movie that’s a little like the games it condemns: people will pay to see children take each other out. Katniss, though, she shows us that love wins, that cooperation beats competition, and that grrl power rocks.

Maybe Elysia will be old enough to see it when the third and final movie comes out. Thirteen does sound about right, now that I consider it. I mean, think what I was doing at that age.

No, don’t.

April 22, 2012

Music from Big Pink

Iconic

.

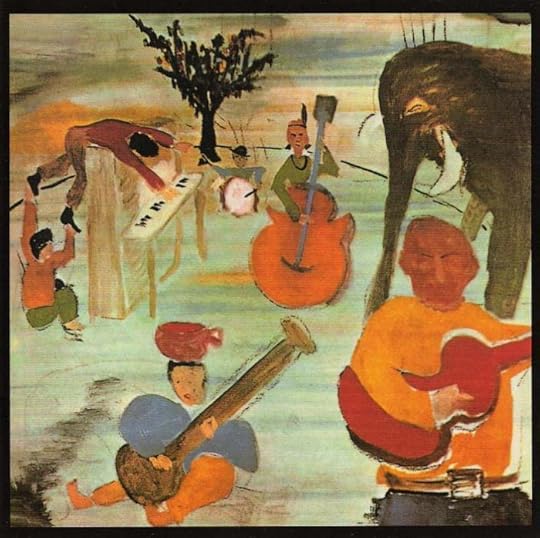

Jimmy and Peter fox had attic rooms in their house on South Avenue, New Canaan, CT, and up there under the eaves we listened to music and told stories and smoked various substances, ate elaborate snacks. One afternoon after I’d turned 16–this would have been in 1968– Jim showed me a new album he’d gotten and put it on his turntable ready to play. First, though, we had to work his hash pipe a while–temple balls from Thailand (very popular, coming back with the kids who’d been fighting in Vietnam). You didn’t just listen to a new album without preparation. I studied the album cover. The painting, Jim told me, a pleasing Gauguinesque watercolor, was painted by Bob Dylan. Whoa. And The Band had been Dylan’s band. Holy shit. On the back side was the title: “Music from Big Pink,” simple photo of an

Yep.

imposing pink house, taken from below. This was the house The Band lived in (maybe), and the recording studio was up there, and Dylan had written there and recorded. It was in West Saugerties, New York. We took a lot of stock in knowing these things and I paid close attention. Maybe one day we’d drive over there and see. My ears grew warm with the hashish and my breath grew important and I could feel my hair. You didn’t listen to an album in order–not the first time. You listened song by song because if you just played it your attention would wander the way it would on a long driving trip and you’d miss everything after the second song, or maybe third. We had a lot of theories like that and talked them over endlessly.

Finally, Jimmy put the needle in the proper groove and played me “Tears of Rage.” I’d never heard such a keening. Jimmy played it again. “Tears of Rage” was sung by Richard Manuel (co-written with Dylan!). Later, Levon Helm said it was the best performance Manuel had ever given. And he did it in the studio. Jimmy Fox was the first kid I knew to have that album. Pretty soon everyone would have it. But that afternoon it was new and fresh and so moving that I couldn’t stop hearing it for weeks, then years.

The next song Jimmy laid on me was “The Weight.”

That was Levon Helm singing, first I’d ever heard of him. Pretty soon, same, everyone would know him. A drummer, singing! And “The Weight” was in the movie “Easy Rider” just that next year. Those slow rhythms, the emotional voices, the falsetto, the songs of loss and sorrow. It all really spoke to us, kids waiting to turn 18 and get drafted, unless we could avoid it.

“The Weight.” Levon Helm sang that.

April 21, 2012

Getting Outside Saturday: A (Little) Nature Essay in Film

So here’s a little Youtube film I made last week to go with the essay I wrote about the wrens in the shack and not putting up screens. Six people have seen it so far. You can be the seventh!

So here’s a little Youtube film I made last week to go with the essay I wrote about the wrens in the shack and not putting up screens. Six people have seen it so far. You can be the seventh!

It’s called………An Uncertain Place

April 20, 2012

Happy Anniversary BP! The Oil Spill Two Years Later

BP recently got an anniversary present: close to $24 billion in net profits for 2011. Happy to know that all is well in the corporate ecosystem.

BP recently got an anniversary present: close to $24 billion in net profits for 2011. Happy to know that all is well in the corporate ecosystem.

Today, at my NRDC blog, “Wild Life,” I talk with Bethany Kraft, deputy director of the Gulf Restoration Program at the Ocean Conservancy about the current state of the Gulf. It’s a fairly comprehensive piece on the most recent scientific results on dolphin deaths, seafood, and damaged ecosystems.

As for BP, the below is adapted from The Tarball Chronicles:

After another fifteen minutes we reach the rig itself. The Deepwater Horizon Rig and the boats around it look like Tonka Toys. The rig platform is lit up by the green nimbus of the sunny and flowering BP logo. Dozens of boats, tiny from up here, gather around the rig, as if trying to protect and comfort it. To us the rig may look like a toy but it is in fact a great metal island, capable of housing over a hundred people. Still with its green logo it appears almost cheery, as it is no doubt supposed to look, and of course the scene looks not just sunny but industrious, with no hint of despair.

In broad daylight it is hard to picture the fiery hell of April 20th, the night when the methane bubble blew up through the well and exploded at the platform, killing eleven, injuring seventeen more, and sending dozens leaping off the platform into the flaming water. What was it like to take that ten-story plunge? The chief Engineer said later that he thought of his wife and his little girl before closing his eyes and making the leap. Those, I am sure, would have been exactly my thoughts.

In the story being told right now the Deepwater explosion was a great tragedy, but also something anomalous, an “accident” of course, a terrible accident. But is something an accident if crucial tests are skipped, if costs are cut, if warning systems are turned off so alarms won’t ring, and if even the CEOs of Shell and Exxon–a Big Oil cohort that is known to stick together–have sworn in front of Congress that the Deepwater Horizon well did not come close to meeting industry standards? Is something an accident if a billion dollar company, the world’s fourth largest, decides it needs even greater profits, and sends a top-down directive to cut costs by 25 percent? “I’m not a cement engineer,” BP’s CEO Tony Hayward told Congress in way of feeble defense, but presumably he had a few cement engineers working for him. He also said famously “I’d like my life back,” a sentiment no doubt shared by the eleven dead crew members and their families.

Far from anomalous, disasters were, by the time of the spill, become commonplace in the world of British Petroleum. Over the past decade the company went from the little brother of oil to one of the big guns, acquiring Amoco and Arco in the process. But during that heady rush the company’s M.O. was to take risks and cut costs, safety be damned. This is not overstatement. BP has led the Big Oil League in deaths and disaster. In 2005, fifteen people were killed and 170 injured when BP’s Texas City refinery blew up due to shoddy safety standards. In July of that same year BP’s flagship for deepwater drilling, the giant off-shore rig, Thunder Horse–Thunder Horse!–was toppled, seemingly by hurricane Dennis but in fact by faulty valves hastily installed. The next year BP hit the disaster trifecta when 20,000 gallons spilled from a rusty pipeline in Prudehoe Bay on the north slope of Alaska.

Which leads to the question: if things happen regularly and for the same reasons do they still qualify as accidents? Which leads in turn to the next and larger question: if we, as a country, keep acting in ways that lead to shocking events, isn’t it time to stop being shocked?

Not that it isn’t shocking. A 20,000 gallon spill, like the one in Alaska, is a disaster. But over 200,000,000 gallons have spilled from the well below me since early April.

We circle the rig again. I stare down to try to see the deeper story. It was down there that eleven people were sacrificed in the name of profit. Is that an exaggeration? Tony Hayward and Carl Svanberg might be scapegoats–and fine scapegoats they are, with diabolical accents to match–but what about the board of directors? And what about the system that created the board? The group and the philosophy that demanded that this company, despite earning billions of dollars, had to earn even more to sate them; that to do so, to provide more billions, a 25 percent cut in operations had to be enacted, even as those operations were expanding downward into new territory, 13,000 feet below the ocean floor? How were those cuts enacted? Simply and systematically: by cutting corners and skipping regulations and eliminating safety measures. Piles of money that could support a small city for decades were being divided between a board made up of a dozen or so people. And yet no one could be bothered to pay a few hundred thousand on tests, nor could they abide a alarms that might slow them down.

Take this down to a personal level and it seems almost inconceivable. This is not the first time I’ve traveled this country and I am always surprised by how decent people are. But where are all those exceptional individuals in a moment like this one? Is it only in large groups that most people are allowed to bury their morals? No healthy individual would ever do to their family or clan what this corporation has done to the people of the Gulf. Individuals would face immediate ostracism. Maybe it’s as simple a problem as the size of the organization, or even the words “organization” and “system.” When profit is laid down as the greatest priority and one’s job–one’s self-interest–hinges on that profit, simple commonsensical goodness flies out the window.

I am wrestling with these ideas in my mind and can’t stem the tide of confusion. It’s too much to handle all at once. In our over-simplified political discourse we talk a lot about the importance of business, but we also talk a lot about freedom and individual rights. But a corporation like BP is about as individualistic as a batch of flesh eating bacteria–there is no debate over what the collective will is: grow and profit, no matter the cost. What does freedom mean when we blindly trust that an entity like BP will not destroy the world we rely on for our health, happiness, and wellbeing?

We don’t stop there, though. Before I came down here I watched the congressional hearings where Tony Hayward testified. A woman jumped up from the back row and waved her hands, which she had painted black, and yelled: “He should be charged with a crime!” She was quickly dragged away. It’s easy to roll our eyes and call her a wacko, relegating her to the category of NFL fans who paint their chests and wear wedges of cheese on their heads. But she is right. Rather than being charged with a crime, this man’s famously inept and dangerous company is being charged with running the cleanup. It is hard to imagine a culture in which this would possibly happen: not only do we trust them, but, when they err, we trust them yet more.

* * *

Praise for THE TARBALL CHRONICLES

and DAVID GESSNER’s Writing on the Gulf Oil Spill

Environment/Nonfiction • Milkweed Editions • September 2011

Winner of the Reed Award for Best Book on the Southern Environment 2011

Top Books from the South 2011 Atlanta Journal Constitution

A San Francisco Chronicle Gift Book Recommendation

“Anyone who wanted a first-hand look at the Gulf after the news cycle ended will find it here . . . a brilliant, thoughtful book.” —Publishers Weekly (STARRED review)

“If you read only one book about the Deepwater Horizon oil spill this year, it should be this one. If you plan not to read any books about it, make an exception for this blunt, funny, eye-opening quest to find the real stories behind the Gulf crisis.”

—Shelf Awareness

For those interested in putting the Gulf crisis in perspective, there can be no better guide than this funny, often uncertain, frank, opinionated, always curious, informed and awestruck accounting of how we’ve gone wrong and could go right, a full-strength antidote to the Kryptonite of corporate greed and human ignorance. –Atlanta Journal Constitution

“Expressive and adventurous. A profoundly personal inquiry into the aftermath of the Deepwater Horizon catastrophe unique in its hands-on immediacy and far-ranging ruminations.”

—Donna Seaman, Booklist

Gessner crafts a powerfully informative but also immensely relatable narrative. He shows that while the national media has moved on to other stories and the oil has sunk to the ocean floor, the full impact of the gulf oil spill remains to be seen and the questions it raised must still be answered. Somehow he succeeds in teaching without lecturing or moralizing, making “The Tarball Chronicles” entertaining and rousing despite its disheartening subject matter.

–Mother Nature Network

“David Gessner is on a roll.” —New Orleans Times-Picayune

“Gessner has the heart and mind of an investigative journalist. . . . Not everyone will be pleased with this Jeremiah in our midst, but the word is a fire and a hammer, and Gessner delivers it well.”

—Mobile Press-Register

“In this highly readable, firsthand account of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, David Gessner considers the catastrophe in the Gulf as a symptom of even bigger economic and cultural challenges that loom in our future. This excellent book is not judgmental, but thought provoking and well worth reading.”

—David Allen Sibley, author of The Sibley Guide to Birds

“Brilliant—the best and most original writing coming out of the Gulf.”

—Scott Dodd, OnEarth magazine, Natural Resources Defense Council

“Plenty of people are writing about the BP oil disaster, but few indeed will be able to make us feel the reality of it like David Gessner can. The likelihood that his account will also be action-filled and darkly funny is pure bonus.”

—John Jeremiah Sullivan, the author of Pulphead

Order or comment on The Tarball Chronicles HERE.