David Gessner's Blog, page 28

September 3, 2014

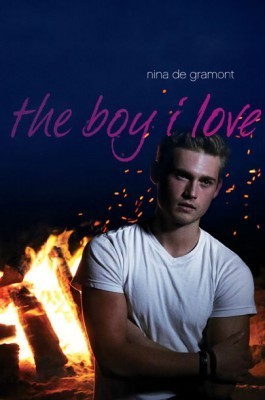

Good Advice Wednesday: Check out Nina’s New Book

My wife, Nina de Gramont, celebrated the release of her new young adult novel yesterday, The Boy I Love, and celebrates her birthday today. The presents have been pouring in in the form of great reviews and blogs. This one came yesterday from Booklist:

My wife, Nina de Gramont, celebrated the release of her new young adult novel yesterday, The Boy I Love, and celebrates her birthday today. The presents have been pouring in in the form of great reviews and blogs. This one came yesterday from Booklist:

The Boy I Love.

de Gramont, Nina (Author)

Sep 2014. 288 p. Atheneum, hardcover, $17.99. (9781442480568).

The day Wren Piner saw the alligator in the river by her North Carolina home seemed to change

everything, and overnight she became famous in her small town. After she begins a new friendship with gorgeous Tim Greenlaw, things fall quickly and completely apart with her best friend, Allie. But just as Wren is convinced that she is falling in love with Tim, he reveals a surprising secret, changing their relationship forever. This fresh and surprising novel has much to offer. The well-drawn characters realistically and believably negotiate difficult life transitions, deal with prejudice and bigotry, and suffer the inevitable emotional pain that comes with falling in love and growing up. Wren might be more confident and self-assured than most teens, but her straight-shooting personality is refreshing and well served by the conversational narrative directly addressed to the reader. Overly heavy foreshadowing detracts from what could have been a suspenseful climactic scene, but Wren’s engaging and inspiring story speaks to the social and economic issues many teens face today. Highly recommended for contemporary

realistic fiction readers.

— Summer Hayes

So today’s bad advice is good: read Nina’s latest!

August 30, 2014

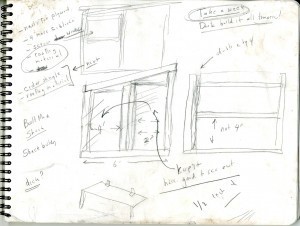

Building the Shack

I’m out in the shack this morning, working on an essay about birds I have seen here. thought I would re-post this piece from the week I built this place:

Robinson Jeffers took eight years to build his stone home, Tor House ,and the adjacent Hawk Tower, both built out of granite and poised on a Big Sur cliff. Mary Oliver’s account of building the cabin behind her Cape Cod home, in Winter Hours, describes no less than a spiritual journey.

As for me, I slammed my writing shack together last weekend.

To each his or her own.

I’m a pretty fast writer and it turns out I’m a pretty fast shack builder, too. But while I may harbor secret dreams of being the greatest writer of all time, I have no such delusions about my carpentry. For one thing I’m not so keen on the whole angles and numbers thing, and while a surprising amount of things in my new shack are level, there are also plenty of things that aren’t. (This writing desk, I’m noticing, as I type this post– my very first shack production by the way– leans to starboard.) One of the main things a young writer learns is that they are not going to be able to support themselves by writing, and my fist attempt at solving that economic problem was by working as a carpenter (a carpenter’s helper really) in Boston and on Cape Cod. I was pretty bad at it, and remarkably insecure when among my more practical co-workers, but some things eventually sank in. What mostly sank in were the slamming, athletic aspects during one winter framing houses on Cape Cod, where moving fast was not just required by my semi-sadistic bosses but by the bracing (a too nice word) weather. In short, I got pretty good at hammering 2 by 4s together.

One of the secrets that house builders know is how fast frames go up, basically going from nothing to house in a few short weeks. Then the finish work starts and goes on forever. When I started writing I was a perfectionist, not showing my work to anyone and taking about five years each to finish my two unpublished novels. I might not have written them at all if I hadn’t learned from framing that the rough draft, the hull of a thing, can be muscled together pretty quick. I also admired one of my bosses, a calm man who showed me a different way to be in the world than my grumbling, judgmental father (and his wrought up Van Gogh of a son).

One of the secrets that house builders know is how fast frames go up, basically going from nothing to house in a few short weeks. Then the finish work starts and goes on forever. When I started writing I was a perfectionist, not showing my work to anyone and taking about five years each to finish my two unpublished novels. I might not have written them at all if I hadn’t learned from framing that the rough draft, the hull of a thing, can be muscled together pretty quick. I also admired one of my bosses, a calm man who showed me a different way to be in the world than my grumbling, judgmental father (and his wrought up Van Gogh of a son).

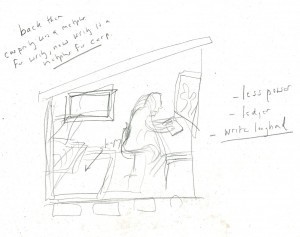

If back then I saw carpentry as a metaphor for writing, this past week I used writing as a metaphor for carpentry. When I set out to build the shack, there were more than a few practical problems, problems that I had no idea how I was going to surmount. I had vowed not to write for the week and the night before I started I did the same thing I often do while writing: woke up at 3 and had ideas. Only these weren’t words, but little drawings in my sketchbook, drawings of what I would build the next day. Then I did something I would never do as a young man. I walked into Home Depot and schmoozed and brainstormed with the people there, who helped me solve a couple of problems. And I solved some problems on my own: like using a screen door turned sideways for the  window I’m looking out right now, giving me a spectacular view of the marsh. (This website actually helped solve another problem: I wasn’t looking forward to building a crowned roof and then remembered the picture of John Hay’s slanted study roof {that I posted here.}) Pretty soon I was into it. “You’re good at getting immersed,” my wife said, which made me proud. It didn’t take long to see that the shack would be a special place for work, even though at that point the only work I’d done was with hammer and nails.

window I’m looking out right now, giving me a spectacular view of the marsh. (This website actually helped solve another problem: I wasn’t looking forward to building a crowned roof and then remembered the picture of John Hay’s slanted study roof {that I posted here.}) Pretty soon I was into it. “You’re good at getting immersed,” my wife said, which made me proud. It didn’t take long to see that the shack would be a special place for work, even though at that point the only work I’d done was with hammer and nails.

I used no power tools and no screws except for the door: just my old framing hammer, some galvanized common nails and coated sinkers, and a handsaw. This was not born wholly out of Thoreauvian idealism. Earlier in the week I bought a power saw at Sears and then discovered, upon opening the box, that some assembly was required,–notably the blade was not attached. I might have gained some confidence in my practical abilities over the last couple of days but I would never, as long as I live, trust a saw on which David Gessner had put the blade. It required a little extra work to do it all by hand, but I still have all my typing fingers.

This morning I brought my bird books, binoculars and telescope down to the shack. The delights here are constant. Clapper rails and herons and egrets. Lots of bluebirds too. The day before my 50th birthday we put up a bluebird house and had bluebirds inside it the next day. Two days later we saw a pileated woodpecker in the yard. The highlight in the shack so far was watching a stark white northern harrier, looking like it had stolen a gannet’s colors, as it hunted, mowing along the top of the marsh grass.

“We need a backshop all our own,” wrote Montaigne. I’ve always been a lover of studies and if you get me started on the subject a certain cabin back in Concord the only way to stop me is to put a plastic bag over my head. One of the fascinating things about Thoreau’s shack was how it solved practical and artistic and personal problems, giving him not just a place to live cheaply, but his subject and a way to be. I don’t expect as much from this place but you never know. Right now my computer battery is running out and so must this post. My plan is to keep this place primitive and have no electricity or plumbing. But there’s a rumor that Bill Roorbach, he of the world famous Bill and Dave’s Cocktail Hour, might be visiting soon and I’ve read that as a young writer/musician he solved some of his own economic challenges working as a plumber and electrician. So who knows? This morning the possibilities, like the view, seem endless.

Bonus pics:

August 26, 2014

Bad Advice Wednesday Greatest Hits: Finding Time to Write

Two missives this week, one from WriterMom, the other from Jean Witlow in Corvallis, Oregon, with very close to the same question. WriterMom: “I teach four sections of composition at two different colleges, and have three kids, 6-8-12. My husband is deceased. I write an infrequent column for the local paper. But that’s it for writing. I want to know how to get my book written when I have no time and never will.” She goes on to describe the book (almost a pitch—first advice: don’t do that—you come off like an infomercial or a flight attendant). And it sounds good, a memoir of her husband and the risk taking that finally killed him. Next, with as little punctuation as possible, Jean Witlow says, “Here I am finally with my MFA and my book basically written it was my thesis but needs some work and I’m going crazy because I can’t work on it half the time and I get a whole day and just sit there and don’t even write. Very depressing, so I avoid it.”

crazy because I can’t work on it half the time and I get a whole day and just sit there and don’t even write. Very depressing, so I avoid it.”

Time. That’s the issue. It’s all around us, moves very slowly and also very fast. Our days are taken up with duties and chores. A simple bad mood can take all morning. A kid’s homework can absorb a night. Jobs don’t take just forty hours, they take forty hours plus the commute and the drinking time to wind down. And there’s fun. Are we not supposed to have fun?

No, we’re supposed to write. That’s what a writer is. Someone who writes. You can have fun doing that. Or have fun later. I had the revelation many years ago that people didn’t respect my writing time. Friends, colleagues, family. They all saw it as a kind of hobby, like collecting bobbins, something you could interrupt at will without harm. Whereas if I had to teach a class, pure respect. “I have to go teach.” So much for whatever agenda my tormentor may have had—teaching is real, teaching commands respect. “Meeting Friday at three?” “No, I have to teach.” Meeting time changed, or if not, I wasn’t expected to attend. But if I said, “No, I have to write.” The reply was, “Oh, well. We all have to write. We’ll see you Friday at three.”

The big shift I made was starting to call my writing work. First to myself, then to family, finally to everyone else. And not just call it work, but make it my work. And not just work, but my job. My number-one task. I had to respect my writing time if I expected anyone else to.

“Can’t make the meeting. Have to work.”

“It’s important, Bill.”

“Well, so’s work. Let me know what you talk about and I’ll give you my two cents later.”

The next challenge is knowing when you’re supposed to be at work. Any other job, you have a schedule. You’re expected at your desk or at the restaurant or at the head of the class at a particular time and place.

So, I started scheduling my writing time in with everything else. I’d do this Sunday nights, just look out across the week realistically and find at least a little time every day, Saturday off or reserved for special projects. Something like this: Monday, busy day. But carve out a tiny ten-minute block after lunch. Use the block, and lunch, too, if possible, to get clear on the next day’s work, to get a sentence started, maybe a paragraph written, something, anything to keep in touch with the project at hand and smooth the way upon the morrow: work. Tuesday, two hours in the morning. Wednesday, holy hominy, jammed. Ten minutes again. Thursday, that two-hour morning block again, ahh, and add an hour before dinner. Friday, all afternoon. Sunday after dinner, since I’m cooking that night, three hours, and that’s before I turn to the composition papers also on my desk.

But what if Friday your kids are coming home from school at 3:00? Well, you have to work. Do what you’d do if you were expected at the office, the restaurant, the classroom. Arrange a play date, get a sitter, enlist a relative, turn on Word Girl, whatever it takes. My daughter liked to sit with me and pretend to write. Now she really does write, and a lot.

Go ahead, schedule a day off on the weekend. Don’t make things so draconian you’re bound to blow it. Be a nice boss. But if you don’t show up as scheduled, fire yourself. But have a soft heart–hire yourself back when you come begging.

If a friend calls and says let’s see that new movie Sunday night, you know what to say: “I have to work.” If the temptation is so great that you can’t resist, go ahead, go to the movie: at least you know enough to feel guilty! And you know enough as well to schedule a make-up block of time. Get those scheduled hours in, every week, one way or the other.

Teaching can be a huge time suck. And rightfully so–those wonderful students. But at a certain point I switched the equation from “Teaching takes so much time away from my writing!” to “Writing takes so much time away from my teaching!” And so I scheduled my teaching, too. Not the classes, that was done for me. But the grading time, the prep time, the conference time. Each class got x hours and no more than x. Which meant there were days I went in with some papers ungraded. Which meant there were days I was less than prepared. But after a while, I learned to get the work done in the time allotted, and not only that, but to get it done well. I also realized I could assign fewer papers that would come straight back to me while getting the students to do more with one another. Remember–whoever’s working hardest in that classroom is learning the most. Put those students to work! You can schedule yourself a whole week off by assigning student presentations, all peer-graded. Let the students bring the papers home. And these economies make you a better teacher in the bargain, especially if they help you to write.

As you get good at scheduling and sticking to your schedule, you’ll find more and more time, more and more blocks big and small in which to report for duty, which is writing, don’t forget. The other stuff is just the way you support your writing.

(Except kids. But kids can play Frisbee. Infants worse. And new mothers, and single mothers, they get full sympathy. Young fathers, almost the same. Yet I’ve known quite a few of both types who kept the work going–tiny increments, it’s true, but all babies grow up if we give them the love. Which means time. But I don’t see anything wrong with approaching yourself at the advent of parenthood or during later crises and asking for a leave of absence. And I don’t see anything wrong with granting such a leave. The job will still be there when you return. Life is various. And leaves give you plenty to write about and plenty of heart to write with when you finally return to your desk.)

You’ll also find that daily, or nearly daily contact with your projects will change the way you approach them. Instead of sitting drumming your pencil and thinking about sex through your whole five-hour Thursday-night block, you’ll hit the ground running. But then again, thinking is your work, too. Also daydreaming. Head in a cloud, which is where the metaphors live. Make time for that. Respect all aspects of your process. You can’t leave work just because you’re not having a productive day! Stay there. Turn the machines on, grab that pencil, look busy. The boss isn’t going to keep you around if you take off every time you’re not inspired. Write notes for the greatest book ever written if necessary, but write. And if you’re not writing, at least look like you are.

Sorry, reading doesn’t count. But it is part of our work, so schedule that, too, just schedule it separately, and bring a book to every appointment. Ten minutes of Middlemarch equals hundreds of hours of People Magazine. And really, at the dentist, sometimes you get a half hour here, ten minutes there, wonderful. And listen to the same book on tape on the way home.

I actually count gardening up to a point, because I can bring myself to a still and receptive place among the weeds, think my way through literary problems, hit the desk ready to proceed.

Similarly, you can write in odd moments. I used to hate waking in the middle of the night. But now, after the third or fourth round of worrying whether I’ll make my flight on my next trip, I plug in some crucial plot or language problem from the project at hand. Why does Mark tell Charles he can’t come to dinner? At first, that flight and its attendant worries will keep cycling through, but pretty soon Mark and Charles take over, and pretty soon again I’m asleep.

In that state, since I’ve been working daily, even if only in small blocks, my mind can keep going. Often I wake up knowing what Mark is up to, the bastard. And when I hit the desk, that bit of dreaming is already done, so I can start writing, writing.

You’ll know you’re getting there the first time someone you’d rather not calls to ask if you’ll be a bride’s maid, a groomsman, if you’ll come plant trees with the employees of some gross polluter. And you say, “No, I have to work.”

If you’ve had to say yes—and this happens—bring your notebook along, carve a little time out of the block that’s been stolen from you, and write–even one sentence is enough, even one phrase. And don’t forget to re-schedule the time you had to miss! You can’t get along on half a paycheck.

As my friend Wes McNair once said to me, “We’re not going to be remembered for going to meetings. We’re going to be remembered for what we write.”

#

Also this week one of my wonderful former grad students has written to ask if I’ll read his book contract. First of all, hooray. Second of all, no, because I’m not an agent or a lawyer, not even close, and bad advice only goes so far. But here’s what I suggest: join the Author’s Guild. They have a free contract service for members. Actual lawyers review your contract to make sure it’s up to industry standard (many are not). They suggest revisions, which most publishers will accept, at least to some degree. Even your agent will be glad for the second opinion. Membership is ninety dollars a year.

Bill Roorbach is a writer in Maine. He didn’t have time to write this.

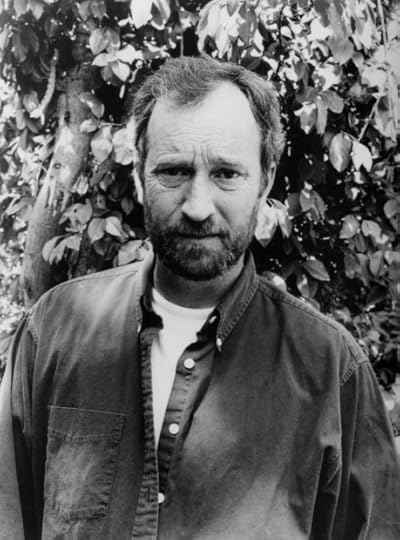

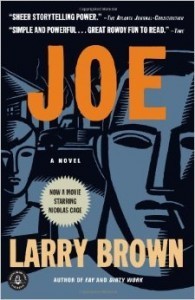

Lundgren’s Book Lounge: “Joe,” by Larry Brown

Larry Brown

The mysterious alchemy that brings books into my life has always fascinated me. I seldom fail to finish books because it’s always so evident that the book in my hands is there for a timely reason, as though there is a god of reading that has placed it there. Often titles appear off the lips of a network of fellow bibliophiles and so recently when friends Monica Wood and Robert Vitesse, voracious readers both, mentioned the astonishing impact of the fiction of Larry Brown on the same day, I immediately went to my shelves and pulled out a copy of Joe and began reading.

I had previously read some of Brown’s short stories and been impressed. But Joe was another animal altogether; for the two days it took to read, I was transfixed. While teaching or gardening or walking the dogs, the bewitching title character was with me. Joe is a creation of the deep South, Mississippi to be exact and Brown hailed from Oxford, so the comparisons with Faulkner are inevitable. But while the Bundren family of Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying have an endearing, almost comical quality to them there is a darkness to the more contemporary Southerners of Brown’s fiction that will cast its mark on your reading soul. Wade Jones, patriarch of a family that resembles the Bundrens in their abject helplessness, is as malevolent a character as you might meet in your literary travels. And Joe, with his myriad flaws, living with his ferocious adherence to a ancient Southern code of honor, is as magnificent a creation as I can recall in recent American fiction.

I had previously read some of Brown’s short stories and been impressed. But Joe was another animal altogether; for the two days it took to read, I was transfixed. While teaching or gardening or walking the dogs, the bewitching title character was with me. Joe is a creation of the deep South, Mississippi to be exact and Brown hailed from Oxford, so the comparisons with Faulkner are inevitable. But while the Bundren family of Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying have an endearing, almost comical quality to them there is a darkness to the more contemporary Southerners of Brown’s fiction that will cast its mark on your reading soul. Wade Jones, patriarch of a family that resembles the Bundrens in their abject helplessness, is as malevolent a character as you might meet in your literary travels. And Joe, with his myriad flaws, living with his ferocious adherence to a ancient Southern code of honor, is as magnificent a creation as I can recall in recent American fiction.

Cleanth Brooks, Faulkner biographer and dean of 20th century American literary criticism, describes Joe thus: “Joe Ransom is a man who insists on running his own life in his own way. He refuses to be controlled by anyone else… Living his life on his own terms makes him a good many enemies, though the fact daunts him not in the least. Yet his is not the arrogance of the bully. He lives by his own code of honor. To shape and present this special kind of character is a formidable test of any author’s powers. It is a test that Larry Brown easily succeeds in passing, for most of his readers will accept Joe’s essential reality.”

Larry Brown died when he was barely 50, apparently of a heart attack. I cannot even imagine what we have missed by his early and untimely demise. Best to simply stop whatever you’re doing and grab a copy of Joe, both to honor the memory of both Larry Brown and Joe Ransom and to experience anew why we read.

[Bill Lundgren is a writer and blogger, also a bookseller at Longfellow Books in Portland, Maine (“A Fiercely Independent Community Bookstore”). He keeps a bird named Ruby, and teaches at Southern Maine Community College.

August 23, 2014

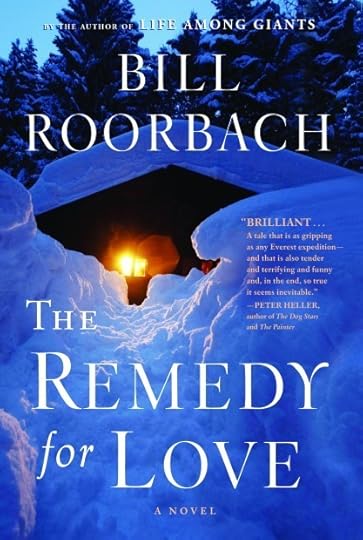

“The Remedy For Love” Book Tour!

Coming October 14, 2014

Save the Date! THE REMEDY FOR LOVE Book Tour is coming to a city near you. Warm thanks to my incredible publisher, Algonquin Books! Valuable prizes for those who come the furthest to each event! Let’s get a drink after! Here’s the schedule as of now:

Tuesday, October 14th, 7 p.m: Longfellow Books, Portland, Maine

Tuesday, October 14th, 7 p.m: Longfellow Books, Portland, Maine

Thursday, October 16th, 7 p.m: Jesup Library, Bar Harbor, Maine

Friday, October 17th, 7 p.m: Emery Center, UMF, Farmington, Maine

Wednesday, October 22, Noon: Portland Public Library

At Sundog Books

Thursday, October 23, 7 p.m: Lithgow Public Library, Augusta, Maine

Friday, October 24th, 7 p.m: Magers and Quinn Books, Minneapolis, MN [A Whiskey Tour event!]

Saturday, October 25th and 26th, Texas Book Festival, Austin, TX [A Whiskey Tour event! ]

Monday, October 27th, 8 p.m: Books and Books, Coral Gables, FL [A Whiskey Tour event!]

Thursday, October 30th, 6 p.m: Watermark Books, Wichita Kansas

Saturday, November 1st, 2 p.m: Lighthouse Writer’s Workshop, Denver, CO

Saturday, November 1st, 2 p.m: Lighthouse Writer’s Workshop, Denver, CO

Tuesday, November 4th, 7:30 p.m: Book Bar, Denver, CO

Wednesday, November 5th, 7:30 p.m: Booksmith, San Francisco, CA

Thursday, November 6th, 7 p.m: Rakestraw Books, Danville, CA

Monday, November 10th, 7:30 PM: Powell’s Books (Hawthorne), Portland, OR 97214

Tuesday, November 11th, 6 p.m: University Books, Bellevue, WA

Monday, November 17th, 7:00 p.m: Talking Leaves Books, Buffalo, NY

Monday, November 17th, 7:00 p.m: Talking Leaves Books, Buffalo, NY

Tuesday, November 18th, 7:00 p.m: RiverRun Books, Portsmouth, NH 03801

Monday, November 24th, 7:15 p.m: Georgia Center for the Book at DeKalb County Public Library

Tuesday, November 25th, 7:00 p.m: Politics and Prose Washington, DC

August 22, 2014

My Shadow Syllabus

I’ll tell you exactly how to get an A, but you’ll have a hard time hearing me.

I could hardly hear my own professors when I was in college over the din and roar of my own fear.

Those who aim for A’s don’t get as many A’s as those who abandon the quest for A’s and seek knowledge or at least curiosity.

I had bookmarked a citation for that fact, and now I can’t find it anywhere.

The only way to seek knowledge is to open your hands and let your opinions drop, but that requires even more fear.

The goals and outcomes I am required to put on my syllabus make me depressed; they are the illusion of controlling what cannot be controlled.

I end up changing everything halfway through the semester anyway because the plan on paper is never what the living class ends up being about.

I desperately needed A’s when I was in college because I didn’t know what else I was besides an A.

Our flaws make us human; steer toward yours. I steer toward mine. That won’t always be rewarded in “the real world.”

“The real world” isn’t the real world.

I realize that I, as the authority figure in this room, might trigger all kinds of authority issues you have. Welcome to work and the rest of your life.

I have a problem with authority figures myself, but I’ve learned how to work with it. Watch my cues.

I think I have more to teach you about navigation than about commas, although I’m good at commas.

This is about commas, but it is also about pauses and breaths and ways to find moments of rest in the blur of life’s machinery.

I hope we can make eye contact.

One of you who is filled with hate for this class right now will end up loving it by the end.

One of you who I believe to be unteachable and filled with hate for me will end up being my favorite.

One of you will drive me bat-shit crazy and there’s nothing I can do about it.

Later I will examine the reason you drive me bat-shit crazy and be ashamed and then try to figure out my own limitations.

There will always be limitations, and without my students I wouldn’t see them as easily.

Sometimes I will be annoyed, sarcastic, rushed, or sad; often this is because you are not doing the readings or trying to bullshit me.

Students are surprised by this fact: I really really really want you to learn. Like, that’s my THING. Really really a lot.

I love teaching because it is hard.

Sonya Huber

Someone in this classroom will be responsible for annoying the hell out of you this semester, and it won’t be me.

Maybe it will be me. Sometimes it is, but often it is not.

I won’t hold it against you unless you treat me with disrespect.

You should rethink how you treat the people who bring you food at McDonald’s, if you are this person, as well as how you treat your teachers.

I hope you are able to drop the pose of being a professional person and just settle for being a person.

Everyone sees you texting. It’s awkward, every time, for everyone in the room.

Secret: I’ve texted in meetings when I shouldn’t have and I regret it.

Secret: I get nervous before each class because I want to do well.

Secret: when I over-plan my lessons, less learning happens.

Secret: I have to plan first and THEN abandon the plan while still remembering its outline.

Secret: It’s hard to figure out whether to be a cop or a third-grade teacher. I have to be both. I want to be Willie Wonka. That’s the ticket. Unpredictable, not always nice, high standards, and sometimes candy.

What looks like candy can be dangerous.

Secret: Every single one of your professors and teachers has been at a point of crisis in their lives where they had no idea what the fuck to do.

Come talk to me in my office hours, but not to spin some thin line of bullshit, because believe it or not, I can see through it like a windowpane.

Some of you will lose this piece of paper because you’ve had other people to smooth out your papers and empty your backpack for as long as you can remember, but that all ends here. There’s no one to empty your backpack. That’s why college is great and scary.

Maybe there’s never been anyone to empty your backpack. If there hasn’t been, you will have a harder time feeling entitled to come talk to me or ask for help.

I want you, especially, to come talk to me.

You can swear in my classroom.

Welcome. Welcome to this strange box with chairs in it. I hope you laugh and surprise yourself

Sonya Huber is the author of two books: Cover Me: A Health Insurance Memoir , and Opa Nobody, both from the University of Nebraska Press. She’s also the author of The Backwards Research Guide for Writers. Sonya has worked as a waitress, an artist’s model, a trash collector, gardener, nanny, dishwasher,video store clerk, researcher for the Minnesota Department of Agriculture, canvassing staff for an environmental organization, labor-community coalition organizer, receptionist, mental health counselor, overnight security staff in a mental health center, nonprofit project manager, editor, associate publisher, reporter, medical proofreader, writing instructor for engineering students, adviser to a student newspaper, and finally a professor. She is a big fan of: the Chicago White Sox, her cool son, trips by plane, train and car, coffee, and reading too much too late at night. She is not so great at: cooking and cleaning, video games, saying “no,” among many other things

August 20, 2014

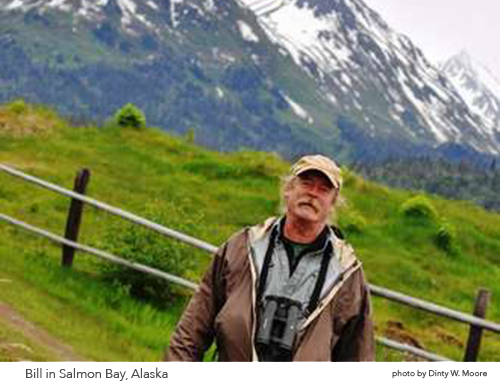

Bad Advice Wednesday: Listen to Bill

Bill is guest starring over at the Lookout-Ecotone blog and we have decided to do a little cross-pollinating:

In House Guest, we invite Ecotone and Lookout authors, cover artists, and editors from peer presses and magazines to tell us what they’re working on, to discuss themes in their writing or unique publishing challenges, to answer the burning questions they always hoped a reader would ask. Bill Roorbach‘s stories have twice appeared in the pages of Ecotone. In this post, he recounts the origin of his story “Broadax Inc.,” reprinted in Astoria to Zion: Twenty-Six Stories of Risk and Abandon from Ecotone’s First Decade.

working on, to discuss themes in their writing or unique publishing challenges, to answer the burning questions they always hoped a reader would ask. Bill Roorbach‘s stories have twice appeared in the pages of Ecotone. In this post, he recounts the origin of his story “Broadax Inc.,” reprinted in Astoria to Zion: Twenty-Six Stories of Risk and Abandon from Ecotone’s First Decade.

__________________________________

“Broadax Inc.” came about because of a ten-day power failure here in western Maine a few years ago, one that had nothing to do with weather (which would be the usual case), but with a technical break somewhere in the grid that caused cascading outages as switches and transformers and other bits and pieces no one of us knows enough about to fix overloaded and burned up—real flames.

I was in the grocery store at the time, waiting in line with my full cart in the glow of some battery-powered emergency lights. The poor woman at the one open cash register had no idea what to do. The cash drawer wouldn’t open without power, so she had no change, and no accounting system. The night manager scratched her head too. I suggested they write down what people had bought and we’d come pay later (I had no cash), but they didn’t even know what anything cost because all that was reported through the laser system. You could write it down item by item, I suggested.

“Well, you can’t leave the store with unpaid merchandise,” the manager said.

In the end there was no solution and all of us in line abandoned our carts. At home, relative comfort. We heat with wood and can cook on the woodstove. And because it’s Maine I keep twenty gallons of water in the basement for such emergencies, so we were able to flush the toilets and could go outside if necessary, no big deal, even as the outage wore on.

What was a bigger deal was maintaining my work life, which is dependent in more ways than I realized on computers and the Internet. I own pencils and still have paper around, so I could write, but I couldn’t access the most recent drafts of two pieces that were on deadline, which is to say I had no access of any kind to the work that was due by e-mail during those days. My cell phone died before I thought to call my editors. I rewrote from memory by hand and put a literal manuscript in the mail—no sign of my old Hermes 3000 typewriter in the barn where last I saw it.

I’d been shopping because we needed food. Now we ate what canned things we had, and pasta. I rehydrated beans from the summer and added stuff I found in the freezer, which remained frozen because it was winter. One restaurant in town used solely gas and they stayed open under candles for two nights till the food was gone and every dish was dirty. Fun while it lasted: bring your own icicle for your drink.

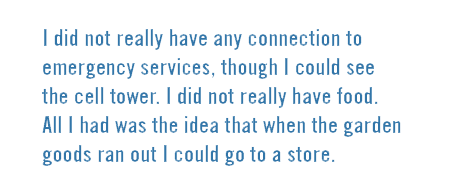

Day seven and it hit me: I did not really have any money. No one does (short of barter, I mean). All we have is electronic promises. I did not really have any correspondents. All I had were electronic addresses, and no way to look up addresses in the physical world. I felt safe, but I did not really have any connection to emergency services, though I could see the cell tower. I did not really have food. All I had was the idea that when the garden goods ran out I could go to a store. But the store had no way to sell till day five, when the generator got there. By then, after two trips to the hardware store (which is very old school in any case, and where they didn’t miss a beat, just made invoices on yellow pads), and numerous trips to help friends, I had so little gas in the cars (simple bad timing) that I couldn’t go anywhere except on skis. Skis were real. The snow was real.

And our house was real. And our wood pile, which saved us.

And so on.

I thought, how about a story where a guy living entirely in the abstract electrical world of corporate money was laid low by someone who could control the access to the abstractions. At long last he’d realize: money doesn’t exist. In the end, he’d have only what he really had, the stuff we can touch, and he’d feel lucky to have that.

Bill Roorbach‘s newest novel is Life Among Giants. His next, to be released in 2014, is The Remedy for Love. His short fiction has appeared in Harper’s, the Atlantic, Playboy, and lots more places, such as on NPR’s Selected Shorts. He was a cake judge on Food Network, but only once.

Tags: Bill Roorbach Ecotone technology house guest astoria to zion

August 18, 2014

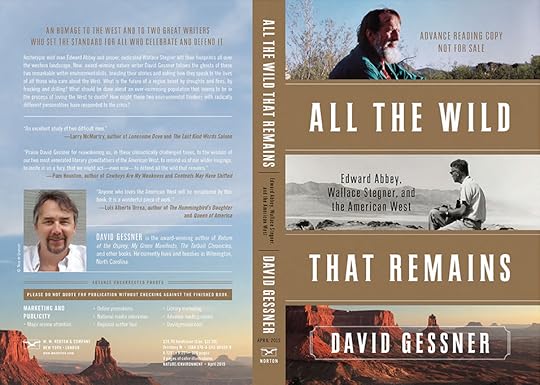

Coming Next Spring…

This is a copy of the cover of the advanced reading copy, not the book itself.

August 17, 2014

Bill’s Sunday Sermon: It’s Not About Strength

So many posts and articles and op-eds and letters and emails about Robin Williams’s sad death, and yet another picture of the media at work, with assumptions run as facts (Williams was back on the sauce? Not true according to his wife, who says he was battling Parkinson’s, and had always battled depression). A lot of moving paeans and memories, too, lovely and sad and instructive. But also a thread of blame: Suicide is selfish. And anger: How could he do this to his family? (Subtext being: How could he do this to me?). And no doubt awakened trauma, as nearly all of us have been through some version of this very public death in our own lives… How could Mr. Williams, or anyone, make such a dire choice?Here’s one FB post, but there were many along the same lines:

“People should be angry when people kill themselves. It’s selfish, passive aggressive and violent. If Robin Williams had shot Michael J. Fox we wouldn’t be writing about his awesome achievements. Suicide is what assholes do.”

But of course, suicide is the result of mental illness. It’s not a choice. We don’t get angry at people with cancer. Or I guess sometimes we do… I knew people who were sure pot caused Bob Marley’s brain cancer, for instance… But compassion makes more sense in either case…

In one discussion, my interlocutor said I insulted those battling cancer by such a comparison, that cancer couldn’t be helped, that suicide was a choice.

I would say illness is illness… Mr. Williams put up a great fight against his for many years, and in the end he lost.

On FB, the wonderful comic brain and fiction writer (and Bill and Dave’s contributor) Meg Pokrass posted the following very helpful quote from David Foster Wallace, who also hanged himself, and who also battled depression for decades before his death:

David Foster Wallace

“The so-called ‘psychotically depressed’ person who tries to kill herself doesn’t do so out of quote ‘hopelessness’ or any abstract conviction that life’s assets and debits do not square. And surely not because death seems suddenly appealing. The person in whom Its invisible agony reaches a certain unendurable level will kill herself the same way a trapped person will eventually jump from the window of a burning high-rise. Make no mistake about people who leap from burning windows. Their terror of falling from a great height is still just as great as it would be for you or me standing speculatively at the same window just checking out the view; i.e. the fear of falling remains a constant. The variable here is the other terror, the fire’s flames: when the flames get close enough, falling to death becomes the slightly less terrible of two terrors. It’s not desiring the fall; it’s terror of the flames. And yet nobody down on the sidewalk, looking up and yelling ‘Don’t!’ and ‘Hang on!’, can understand the jump. Not really. You’d have to have personally been trapped and felt flames to really understand a terror way beyond falling.”

In Victorian times, mental illness was seen as a character issue. Now we know it’s a health issue, as divorced from character as any other health issue. As is addiction. There’s no logic involved–there’s just terrible, terrible pain and the wish to end it. I agree wholeheartedly that suicide is preventable… But our healthcare system isn’t set up to do so reliably. No help until you’ve hurt yourself or others, and denial in every corner… To blame a suicide for her actions is to blame the victim, I’m sorry, and such blame is a huge part of the problem…

I’m not saying being angry doesn’t make sense! It’s just where to aim it. My grandmother would always say she was angry at God. He could handle it, in her estimation…

I guess this suicide as criminal or sinner nonsense comes from old Catholic and other religious ideas? That it’s a sin? Or insurance companies, who want to make sure it’s viewed as a crime?

To those still feeling justified in anger: do you find that your anger helps those left behind or helps anyone?

Anger, of course, is one of the stages of grieving. I give you that!

I see that the Westboro Baptist Church people (of “God Hates Fags” fame) is set to protest Mr. Williams’s funeral… And there does seem a connection between seeing sexuality and mental health as character issues, or religious… As if genetics had never been available to the discussion… Anger isn’t far from hate, seems to me. And interesting that depression is sometimes characterized as anger turned inward… As if depression or even anger could be helped! I’m sorry for your losses, and all of our losses…

A friend wished aloud that Mr. Williams had had the strength to fight his demons, that he could have gone on to help so many others in his predicament, been a champion in the fight against depression, and therefore mental illness.

But again, it’s not about strength. And of course he was a champion, and lived a life in public that takes more strength and more character than we can imagine–or else we’d all do it… He was very, very strong, is what I’m saying, but he had an illness that made that strength beside the point…

Today marks the advent of a new feature: Bill’s Sunday Sermon (There may be a Dave’s Sunday Sermon from time to time, too!). My chance to rant. I come from a long line of Congregational ministers, but have turned out to be a mystical atheist.

August 14, 2014

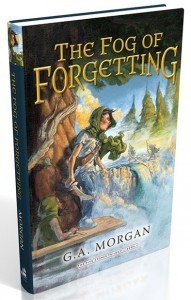

Lundgren’s Book Lounge: “The Fog of Forgetting,” by Genevieve Morgan

I’ve never been an ardent reader of the genre called ‘young adult’ fiction, probably because such books didn’t seem to exist when I was a young reader… or if they did, I was unaware of them. Recently we have seen an explosion of books categorized as Y.A., including many that transcend the limitations of the category of ‘young adult’: these are simply gorgeously written stories whose main characters happen to be kids.

Chief among books in this super-genre (let’s call it ‘Y.A. for everyone’), is Genevieve Morgan’s beautifully rendered tale, The Fog of Forgetting. Book 1 in a proposed trilogy, Fog of Forgetting is a mesmerizing, dreamlike account of a group of youngsters who become lost in the ocean fog while on a  forbidden boating excursion off the coast of Maine. They wash ashore on the island of Ayda, a fantastical world reminiscent of both C.S.Lewis’ Narnia and Tolkien’s Middle-earth. Ayda is composed of four realms locked in an ancient struggle for control of the island. Each of the realms possesses a stone of power, but the fifth stone is missing. Into this maelstrom of intrigue, author Morgan deposits five youngsters who quickly become pawns in the battle for supremacy as if in fulfillment of an ancient destiny.

forbidden boating excursion off the coast of Maine. They wash ashore on the island of Ayda, a fantastical world reminiscent of both C.S.Lewis’ Narnia and Tolkien’s Middle-earth. Ayda is composed of four realms locked in an ancient struggle for control of the island. Each of the realms possesses a stone of power, but the fifth stone is missing. Into this maelstrom of intrigue, author Morgan deposits five youngsters who quickly become pawns in the battle for supremacy as if in fulfillment of an ancient destiny.

Clearly much of this novel is Morgan’s paean of praise to her childhood memories of summers in Maine, where she discovered the secrets that lay deep in the fog. Part fairy-tale, part psychological mystery, full of political intrigue and a masterful bildungsroman, this a book to be read and savored by everyone. Deeply philosophical about the nature of loss and sibling relationships and loyalty and courage, Fog of Forgetting will remind one of the joys of a summer in Maine while also provoking thought and reflection regarding the nature of existence. It is the perfect book to be read together and discussed by young and older readers… Y.A. for all!

[Bill Lundgren is a writer and blogger, also a bookseller at Longfellow Books in Portland, Maine (“A Fiercely Independent Community Bookstore”). He keeps a bird named Ruby, and teaches at Southern Maine Community College.]