David Gessner's Blog, page 23

January 7, 2015

Ed Abbey’s FBI File

I have a new essay in Orion, adapted from my forthcoming book, ALL THE WILD THAT REMAINS. (April 2015.)

I have a new essay in Orion, adapted from my forthcoming book, ALL THE WILD THAT REMAINS. (April 2015.)

It includes these sentences:

“As acting editor of the University of New Mexico’s literary magazine, The Thunderbird, Ed Abbey decides to print an issue with a cover emblazoned with the words: ‘Man will not be free until the last king is strangled with the entrails of the last priest!’ The quote is from Diderot, but Abbey thinks it funnier to attribute the words to Louisa May Alcott.”

Funny guy, that Abbey.

You can read the whole piece in Orion HERE.

I will start posting more short sections of the book as we get closer to publication. The idea is to get you, yes you, to buy it.

January 3, 2015

Getting Outside Saturday: Southern Louisiana Edition

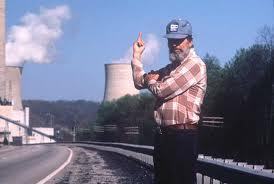

We have made our way down to Venice in southern Louisiana. Yesterday hooked up with Dave Muth for a Christmas bird count. Amazing amount of birds, several of which Hones and I had never seen before. Spectacular abundance in the shadow of the oil plants, right off of Halliburton Road. In this place the future seems to be fighting it out. A fragile spit of land, destined to be underwater by the end of the century, full of wildlife and beauty (this morning we watched an otter slink across the road), while also the virtual front lines of our relentless attempts to extract fuel out of earth and sea. (All photos by Mark Honerkamp.)

Same scene with refinery fire, not sunrise.

Pelicans hanging.

Avocet, Stilt, Dowitcher

Ibises

Writin’

King Rail.

Fog on the Mississippi.

Halliburton (misspelled).

December 30, 2014

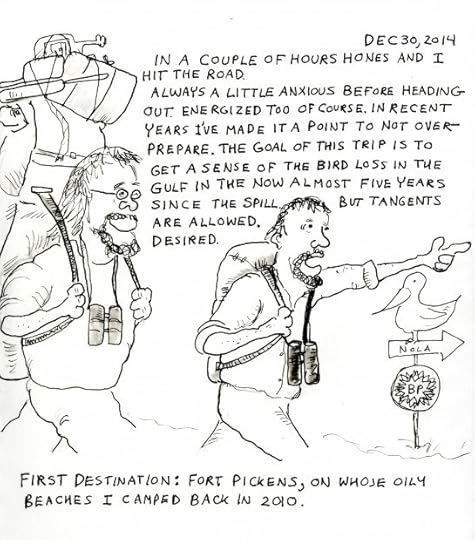

Return to the Gulf: A Cartoon Journal

So I’ll try to do a few of these from the road, but I’m pretty low tech–no smart phone–so I don’t really know how I’m going to scan them. Maybe I’ll run into a guy down at the docks with a scanner. If not, I’ll just post them all when we get back.

And in real life:

December 29, 2014

The Emotional Trajectory of Publishing a Nonfiction Book

1. Hey, I wonder what that’s all about. How come I’ve never heard of this?

1. Hey, I wonder what that’s all about. How come I’ve never heard of this?

2. This seems more interesting than it first appears. More people should know about this.

3.OH MY GOD I HAVE AN IDEA FOR A BOOK THAT IS GOING TO CHANGE THE WORLD.

4. I will go ahead and accept your publication offer, but you should count yourself lucky that you are getting this book so cheaply. I’ll remember this when I’m famous.

5. All right, let’s settle in and nail this thing.

6. Humming along so far; at this rate I’ll come in ahead of deadline.

7. This project is more complicated than I realized/ doesn’t fit my original idea/requires me to do a lot more research than I expected/isn’t as original as I thought.

8. I should probably pause and set up the social media accounts for this book, so there will already be a lot of buzz around the book when it finally appears.

9. I think I have an idea for a better book than this one. I’ll finish this on up quickly so I can write the next one, which will really change the world.

10. I need a few weeks away to clear my head and get some perspective. Where’s the beer?

11. I HATE THIS BOOK WITH THE WHITE-HOT INTENSITY OF A THOUSAND SUNS.* PLEASE LET ME DIE BEFORE I HAVE TO FINISH IT. THIS IS MY LAST BOOK EVER.

12. Oh, book . . . you’re not so bad after all. We were probably meant to be together. Let’s see if we can make it work.

13. I might just finish the son of a bitch after all.

14. This book is actually quite brilliant. As long as the publisher doesn’t bungle the marketing, it will probably win a bunch of awards.

15. Please don’t make such stupid suggestions about my work. If you think you know so much about writing, why don’t you quit your editing job and write your own damn book?

16. This isn’t going to push back the publication date, is it?

17. I liked the other cover design better.

18. Why don’t you find people to blurb my book? I wrote the thing—you’re supposed to do everything else.

19. WHY HAVEN’T YOU PUBLISHED MY FUCKING BOOK YET?

20. Is there going to be a parade or anything today?

*Thanks to Diane Chambers on Cheers for this eloquent curse.

Jim Lang is the author of Cheating Lessons: Learning From Academic Dishonesty. Follow him on Twitter at @LangOnCourse or visit his website at http://www.jamesmlang.com.

December 24, 2014

December 23, 2014

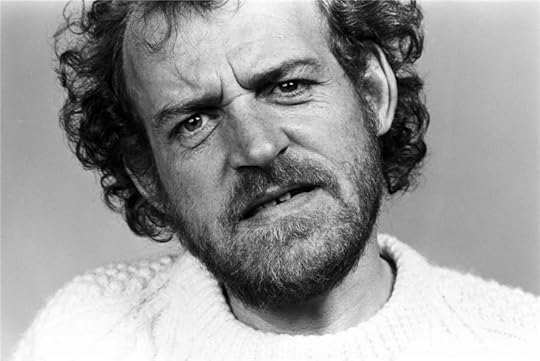

Goodbye, Joe

Joe Cocker is one of those artists that surprise you when you stop to look: thirty albums over forty years, many of them live. The last one to make a big impression on me was Organic, which came out in 1996, possibly the last new LP I ever bought. It has “You Are So Beautiful to Me” on it, and Van Morrison’s “Into the Mystic,” among many others, a guy who made hits out of covers repeatedly by revealing the soul beneath the most familiar of lyrics, that hoarse, tuneful tenor, the struttingly spastic performances, the consummate weird. He just got better as he got older, and maintained a big career dotted with comebacks, something heartbreaking about the guy, but maybe only from the outside. He died of cancer, age seventy, married to the same woman 27 years, big sense of humor, something dark there, too…

Every obituary will mention “A Little Help from my Friends,” and ought to–it’s genius, here at Woodstock, via YouTube:

It made me cry, which took me by surprise, a guy putting everything into it, everything, which is the best we can do, and hope John Belushi sees fit to imitate us, even right behind our backs…. (I also dig the the Carnaby Street high heels.)

I don’t know. I just love the guy, and the position he’s taken in my life over the years, a companion in sadness and joy, and gone.

And just found this–our man LAST YEAR, full arena, illin’, still hitting the screams forty-some years later…

December 21, 2014

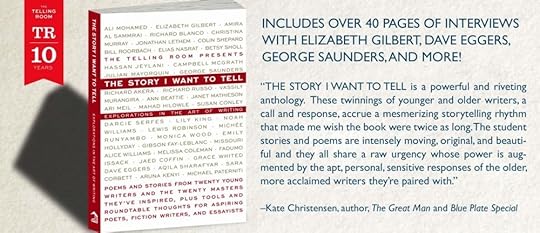

Lundgren’s Book Lounge: “The Story I Want to Tell,” by The Telling Room

Shortly after moving to Portland over a decade ago in an attempt to escape the maw of the Big City that was alternately invigorating and trying to devour me, a friend introduced me to Susan Conley. At the time Susan, along with fellow writers Sara Corbett and Mike Paterniti, was in the early stages of creating a non-profit to support student writers in the Portland immigrant community and beyond, with an eye towards publication as a way to raise the stakes for the writers and the collective consciousness of their readers. Having worked extensively with student-generated publications in the NYC public school system, I was aware of both the potential and the limitations of such initiatives… it seems that many readers and critics find the work of student-writers to be endearing and empowering and yet not worthy of consideration as ‘serious’ literature.

Shortly after moving to Portland over a decade ago in an attempt to escape the maw of the Big City that was alternately invigorating and trying to devour me, a friend introduced me to Susan Conley. At the time Susan, along with fellow writers Sara Corbett and Mike Paterniti, was in the early stages of creating a non-profit to support student writers in the Portland immigrant community and beyond, with an eye towards publication as a way to raise the stakes for the writers and the collective consciousness of their readers. Having worked extensively with student-generated publications in the NYC public school system, I was aware of both the potential and the limitations of such initiatives… it seems that many readers and critics find the work of student-writers to be endearing and empowering and yet not worthy of consideration as ‘serious’ literature.

The newest publication by The Telling Room, the non-profit that resulted from the fruit of Susan and Sara and Mike’s labors, will hopefully put the lie to that myopic perception. The Story I Want To Tell: Explorations in the Art of Storytelling is a collaborative endeavor between student writers and established authors… except these are not your ordinary run-of-the-mill authors. Check this list: Elizabeth Gilbert, Jonathan Lethem, Rick Russo, Monica Wood, George Saunders, Lily King, Melissa Coleman, Dave Eggers, Ann Beattie, Lewis Robinson, Bill Roorbach, Richard Blanco, along with the three aforementioned Telling Room founders and you have a group of the best and the brightest in contemporary American literature. But what is most revealing about this collaboration is that the student writers, whose earlier pieces inspired responses from the established authors, more than hold their own. The work of the students is literature that deserves to be read and judged on its merits and not limited by the cloying classification of the ‘student writing genre.’

The newest publication by The Telling Room, the non-profit that resulted from the fruit of Susan and Sara and Mike’s labors, will hopefully put the lie to that myopic perception. The Story I Want To Tell: Explorations in the Art of Storytelling is a collaborative endeavor between student writers and established authors… except these are not your ordinary run-of-the-mill authors. Check this list: Elizabeth Gilbert, Jonathan Lethem, Rick Russo, Monica Wood, George Saunders, Lily King, Melissa Coleman, Dave Eggers, Ann Beattie, Lewis Robinson, Bill Roorbach, Richard Blanco, along with the three aforementioned Telling Room founders and you have a group of the best and the brightest in contemporary American literature. But what is most revealing about this collaboration is that the student writers, whose earlier pieces inspired responses from the established authors, more than hold their own. The work of the students is literature that deserves to be read and judged on its merits and not limited by the cloying classification of the ‘student writing genre.’

As Pulitzer-winning author Russo pointed out in an interview, “I think most young people don’t realize they have a story to tell, and I think that’s particularly true of kids who come from other cultures or kids who do not have… money or privilege in their background… In fact they have some of the most important stories to tell. These are stories the rest of the world needs to hear.”

The format of this powerful volume, with descriptions of the writing process and interviews with the the mentor-authors and writing prompts designed to spark the creative juices of even the most reticent student-writer, makes it the perfect gift for the young writer or teacher on your holiday gift list. It will entertain, inspire and broaden your view of humanity and of literature.

See The Story I want to Tell video here. Featuring Elysia Roorbach, as Girl Reading with Dad.

[Bill Lundgren is a writer and blogger, also a bookseller at Longfellow Books in Portland, Maine (“A Fiercely Independent Community Bookstore”). He keeps a bird named Ruby, and teaches at Southern Maine Community College.]

December 19, 2014

We Celebrate our 1000th Post!

Hard to believe but Bill and Dave turn 1000 today. 1000 posts. For many years now we have carried on the tradition of blogging started by our great-grandfathers, Ebenezer Roorbach and Ernst Gessner the eighth. May we live to see 10,000!

A recent trip to the Google Analytics store provided me with a list of our ten most popular posts. Here are three from Bill and three from me:

Bill’s top posts:

Bad Advice Wednesday: Steady As She Goes! (October 3, 2012)

Review of Wild, by Cheryl Strayed (June 25, 2012)

And the Oscar for Revision Goes to… (February 24, 2011)

Dave’s top posts:

Ultimate Glory (January 26, 2012)

Everything you Ever Wanted to Know About Truth in Nonfiction But Were Afraid to Ask (March 28, 2012)

What Kind of Annoying Writer Are You? (March 8, 2013)

(Couldn’t find the original of “Annoying” so I re-posted)

And a couple more we like from Dave:

The Top Ten Sexiest Nature Writers in History

And from Bill:

Bill’s Sunday Sermon: It’s not about Strength (Upon the death of Robin Williams)

We’ve also had great posts by over 60 guest writers, like Nina DeGramont, Monica Wood, Bill Lundgren, Debora Black, Dinty Moore, Luis Urrea, John Lane, Kristen Keckler, Richard Gilbert, Mark Honerkamp, Jim Lang, Eli Hastings, Colin Hosten, Jonathan Evison, David Abrams, Heidi Gessner, Kerry Headley, Erika Robuck, Lee Martin, Crash Barry, and on and on, and in fact our top post of all time, Twelve Habits of People Who Don’t Give a Shit About Your Inner Peace, was by guest blogger Katherine Fritz, with over 56,000 views. Also in the top ten was our friend Katherine Heiny’s Origami and the Art of Fiction.

And finally, we are happy to note your participation: 7,250 comments, over a million views.

[Note that Bill is only shorter than Dave in Dave’s cartoons.]

(Actually I topped out at 5’11” and a half and though I’ve shrunk an inch I think I still have an inch on Bill, both in the cartoon and real world. Also I’m as tall as a flood of breaking ice.)

[Okay, Bill topped out at 5′ 10′, shrank an inch, but got it back with my neck surgery. But I weigh more, much of the time.]

The real Bill and Dave celebrating:

And doing our famous ventriloquism act:

And camping on the beach (god I’m choking up):

Please Like us with the FB button up there in the upper right of our page and hear about every damn post. Because we need all the friends we can get! Like this post, too.

December 17, 2014

Table for Two: An Interview with Debut Author Annie Weatherwax

Annie Weatherwax

Debora: Annie, if we were really here at Bistro C.V. you would be able to see how edgy this place is. It’s a good pairing for your new novel! Let’s go sit at the bar. My friend is bartending this evening. She knows all about the wines—which are fabulous here. And we’ll have the opportunity to sample a nice variety, since I want to find out everything about you and your book. But first, Annie, welcome to Bill and Dave’s Cocktail Hour, cheers and congratulations on, All We Had.

Annie: I’m thrilled to be here. Thank-you for inviting me and I can’t wait to try a little wine!

Debora: Let’s begin with your narrator, Ruthie Carmichael. For me, she was totally unexpected, a 13 year old as the story opens. And what a voice—aware, blunt, observant. She definitely speaks here mind. Where did she come from? How did you land on her?

Annie: To me there is nothing more refreshing than the perspective of a spunky teenaged girl.

Ruthie has an unfiltered voice, a voice that has yet to be tempered by the self-consciousness of adulthood. There is simplicity to her wisdom. How did I land on her and where did she come from? There are some hard truths in this novel, and I couldn’t imagine telling it from any other perspective. She has a blunt honest way of seeing the world, which is often humorous, and I hope her humor makes it easier for the reader to digest the some times harsh realities of this story.

Debora: Oh you’ve crafted Ruthie perfectly. She could easily have been one of my inner city eighth graders. In those first pages when Ruthie starts telling us about the latest man in her mother’s life—Ruthie sitting there watching that mustache of his—I was laughing so hard as she lays it all out for us, and I knew this girl would be talking straight and this book was going to be very, very interesting.

Annie: Yes, I want the reader to get a sense of who Ruthie is right away. I want them to hear her voice. Her voice, in many ways, carries this novel. It’s dark, sardonic and humorous. The entire novel rides the line between comedy and tragedy. In fact, all of my work, both visual and literary, is infused with this sensibility. I’ve often referred to it as, “comic realism.” It’s a perspective that feels imbedded in my DNA.

Debora: Every character certainly holds her and his own in the way you’ve written them. But Miss Frankfurt was another favorite of mine. Just exactly how much does she know? Does she know or guess, for example, what happened to Peter Pam? What accounts for her change of heart toward Peter Pam’s overall transgender experience?

Annie: Miss Frankfurt knows everything. She’s got eyes in the back of her head. She’s the principal of Fat River High School and in many ways Fat River is her town. Despite her off-putting manner and the fact that everyone is scared of her, she cares deeply about the community—much of which is made up of her former students. Peter Pam was once Miss Frankfurt’s favorite student, but she never approved of Peter Pam’s transgender identity. When the economy collapses, when businesses close, when neighbors begin to lose their homes and tragedy befalls the elderly couple across the street, the town pulls together. What matters most comes into focus and Miss Frankfurt softens her views.

Debora: Fat River. What an interesting place. Nothing is quite what it seems here. Fat River isn’t fat, it’s mostly dried out. The Olympic hopeful is wheelchair bound. The female waitress isn’t female. And junk turns out to be treasure. It’s an entirely skewed construct. Can you enlighten us?

Annie: The comedian George Carlin once said that “…. language is a tool for concealing the truth.” And the truth is often the opposite of what we initially see. Things are never what they are purported to be and if they are, they lack dimension and dimension is a premium in all forms of art. What makes characters and images compelling is this tension between opposites. Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa captures our imagination because her expression is conflicting; it’s at once innocent and devilish. Similarly, the photograph of Marilyn Monroe standing over the subway vent is iconic because she’s trying to hold down her dress, but why then is she deliberately standing over something that is clearly blowing it up? The message is contradictory. Opposites create tension and tension is what interests me. I hope I managed to build everything—my settings, my dialogue, my characters—with this same construction.

Debora: Yes, in my opinion, you are very successful in this. In fact my favorite moment occurs about a third of the way in when Salvador Dali shows up. Without giving everything away, I’ll simply mention that what Ruthie has to say in this moment not only teaches me something important about Salvador Dali but also encapsulates for the reader—in a kind of comical, certainly surprising, but also a devastating way—what, for me, becomes the most important and very universal theme regarding the ways we are able or unable to construct our lives. Annie, as I’m thinking on this, I’m wondering if it’s fair to say that the very themes are in conflict with each other?

Annie: It’s all about order and chaos. On the face of it, these motifs seem in conflict with each other, but they have a synergistic relationship, which is evident and necessary in all aspect of life. Art and science alike depend on the interplay between order and chaos.

Debora: There are so many funny moments in this book. You write it all in so subtly that the reader really has to be there intellectually participating in the scene. I love it, for example, when those binoculars show up. Hilarious! And then all the spying that is going on already, escalates. So many other things that you present us with are about seeing and interpreting. Will you talk about this idea?

Annie: I think what you’re talking about is sight and insight. Insight is the capacity to gain a deep intuitive understanding of a person or thing. It is through sight that we have insight. It’s why when we see someone fall we flinch as if we’ve experienced the fall ourselves. Mirror neurons or “empathy neurons” fire off in our brains and these neurons are directly linked to seeing, either with the eyes or in the reader’s case, with the eye of the imagination. If as a writer, I just told you that someone fell, it would have little effect, but if I described it in a way so that you could see it, you would more likely have insight into how it felt. Humor works the same way. Saying something is “funny” does not make it funny. Presenting the reader with deliberately crafted visual details in order to garner the specific insight, “that’s funny” is the best way to get your reader to laugh.

Flannery O’Connor once said that “Everything has its testing point in the eye, and the eye is an organ that eventually involves the whole personality, and as much of the world as can be got into it.”

Understanding this was part of O’Connor’s brilliance. It’s what allowed her to write about the Misfit in her famous story, “A Good Man is Hard to Find,” with such compassion. He kills an entire family with no remorse. But because O’Connor wrote that character so we could see him, we feel for him. We have insight into him and our hearts break for him, even if just a little.

Debora: Earlier you mentioned that you present us with some hard truths, and indeed there is a roughness to Rita Carmichael, Ruthie’s mother. I imagine readers will have a lot to say about her. But you know the most memorable thing for me comes late in the pages when she says I’m tired Ruthie. It’s all in there, Annie. A lesser writer would have embellished here, or worse, not realized. But you know Rita inside and out and you know exactly what words give expression to her. One of the great strengths in your writing overall is the dialogue, it’s completely authentic—pitch perfect.

Annie: It makes me so happy to hear that. Who a Character is, what makes them tick, how they are damaged and what their coping mechanisms are should be apparent in everything they do and say.

Debora: I’m really into minimalism in general. Those single word chapter headings! They totally rock, and I must confess that, as a writer, I’m very jealous of them. Because it’s not just the title but how it represents what follows—like the title of a piece of art—which I liken your scenes to be. Installations of a sort.

Annie: Yes! Thank you for noticing that. Much like the title of a painting or the artistic statement at the beginning of an art exhibition, my chapter titles are meant to nudge the reader into interpreting the section a certain way. They are meant to serve as the intellectual framework through which to experience the work that follows them. I do like to think of my novel as a collection of paintings, each one capturing a specific mood with the entire body of work culminating into one grand expression.

Debora: Annie I came to know you as a writer, but many people likely know you first as an artist. I’m always a little startled by artists, like yourself, who successfully cross over into other artistic realms. I mean I know for certain that if you handed me some brushes and tubes of paint, the only thing I could render is a big fat muddy mess. How did you come to be a writer?

Annie: I knew from a very early age what I was meant to be. And that was not a writer. I was meant to be a visual artist. My mother claimed I was born with a paintbrush in my hand. My bedroom where I grew up was a revolving installation. There were always streamers and colored shapes hanging off the ceiling. In high school the room was taken up with art supplies and this ridiculously giant easel. In addition to all that, I’m dyslexic. I grew up not knowing how to read and spent my early childhood devising ways to hide it. But in fifth grade when I got my first creative writing assignment, it was as if a secret door opened up inside my brain. The assignment was to write two paragraphs describing something we loved. So I took my pad of paper and pencil and went outside to the creek behind my house. To me, at the time there was no question what a pencil and paper were for, they were meant for drawing pictures, so I simply drew a picture with my words. The teachers actually kept me after school to ask me where I’d copied my paragraphs from.

I ended up going to Rhode Island School of Design. For many years I earned a living sculpting superheroes and cartoon characters for Nickelodeon, DC Comics, Warner Brothers, Pixar and others. Because of my dyslexia and my aptitude for visual art, I never took my prospects as a writer seriously, but that early experience stuck with me.

What I’ve finally come to realize is that fiction writing is many things. It is a mining and sifting through of the raw material of life until something of substance emerges—a story line or character worth pursuing. But the true task of a writer is to elicit an image—a rich and expansive picture of the world written on the page. As an artist, the craft of writing for me has less to do with the study of literature, or even with writing proficiency, and much more to do with the disciplined skill of seeing and seeing is what I do best. At some point I realized that writing was just an extension of my visual art.

Debora: I do believe that we can all learn to write at higher levels of skill and proficiency. But on the other hand, in the area of creative writing, I think there is also a component of a certain something that we say is talent. After all, there is writing and then there is writing. Have you ever thought about what it is that looms inside you and how you mange to get it on the page? What your special skill set might be? Can you try to identify some of that for us?

Annie: Having dyslexia can often feel like a kind of deafness or blindness, especially for a writer. There’s a whole segment of the world that feels out of reach or off limits to you. Although I am a much better reader than I ever was, I still at times feel this very deeply. It took me my whole life to appreciate it, but dyslexia, I now realize, has hidden powers.

Dyslexics are often highly visual and creative people. People with dyslexia see in 3D, very little registers as flat, which is in part why printed letters cause such difficulty. My writing is inspired largely not by what I read, but by what I see. Seeing is not simply registering the name of thing one sees. It’s a very complicated skill or to use your word, “talent” and I have been honing this talent all my life. I mourn my difficulty with reading but I see a richness and level of detail most people miss. Reading may be difficult for me, but I have a catalogue of images stored in my brain, and as a writer these images have become my vocabulary.

My sharpened sense of sight has taken me to astonishing places. Most incredibly to this one.

Debora: What goes through your mind at the start of a new artistic project? And what is your process as you go to work on it?

Annie: Fear and anxiety are always lurking about, the trick is to control them and the only way to do that is to do the work. I learned this through my career sculpting superheroes and cartoon characters. Each project would start the same — with an intimidating block of brown clay. Eventually it would end up as a fully realized character. Batgirl, Superman, Jimmy Neutron, Darth Vader, Big Bird, Bugs Bunny, Marge and Bart Simpson—hundreds of my original prototypes line the shelves in my studio. It was only by facing the block of clay over and over again, that I learned to quell my self-doubt.

Almost everything I know about writing, I learned by understanding the process and the language of visual art. As an artist, I was trained how to capture the nature of my subject by amplifying the qualities that make that subject distinct or noteworthy. When I paint or sculpt a character I need to recognize what gives a face a certain expression or a body a certain gesture. I need to decide which features to accentuate in order to fully capture the character. When I write, I do the same thing.

The process I use for unearthing a character in a hunk of clay is the same process I use as a writer. A sculptor would never fill in the details until the structure underneath has been fully formed, so as a writer I work each piece, crafting it from all directions, leaving broad impressions everywhere. I jump back and forth from section to section in no particular order. I don’t write in complete sentences. I don’t bother with spelling until the shape of my story and the authenticity of my characters have completely emerged. Painters build their canvases much the same way, layering in color, laboring on the drawing underneath, sketching in the composition before tightening it up. My life as an artist has taught me how be alone and how to maintain focus. I’ve learned to be patient, persistent and disciplined and to sometimes let a character emerge on its own.

Debora: I used to be the curator of a fine art gallery. Once, two of the artists that we represented out of Denver—very developed painters—came up to Steamboat to do some plein air work. The big laugh that evening was how one of them completed his painting then threw it across the highway in disgust. Will you talk for a moment about artistic evaluation? Is it important or not? And how do you, Annie, who is a painter and a sculptor and a writer, make evaluation over your work?

Annie: Artistic evaluation is an integral part of the creative process. Without it, the process is more like occupational therapy—a mindless busyness lacking a deeper goal. As a visual artist I am constantly stepping back from my work and asking myself these questions: Does it look right? Does it feel right? What does it mean? As a writer, I do the same. Honest artistic evaluation is a disciplined practice, one that requires the artist to detach from their work because your ego will inevitably warp this process. It requires an uncluttered objective vision. Understanding and evaluating criticism from others demands the same thing. Of all the lessons I’ve learned from a lifetime as an artist, this lesson has been the most valuable. Moving the ego out of the way takes conscious effort. It lessens the angst and eases the process not just in creating art but also in living life.

Debora: Annie, you seem to have brought us to the perfect place to finish. And you are leaving me—all of us, I should think—with an enormous amount of bright energy to carry forward. What a great time it has been hearing about your book and your artistic ideals. Thank-you so much for being with us. Can we end by you sharing with us a last thought that is important to you regarding All We Had?

Annie: I do hope readers enjoy the book and that it delivers a larger message about the damaging effects of economic inequality. Artistically, I hope the book is understood within the context of my entire body of visual work. To begin that conversation I invite readers to visit my website http://www.annieweatherwax.com and read my artistic statement.

Bad Advice Wednesday: Just Write (2)

Blinders are not all bad.

Why did I call my graduate class this coming spring “Just Write”? Well, “Just Write, Baby” seemed potentially sexist. And “Just Fucking Write” (which was my first choice) kind of crude. But the point, and I bet you get the point already, is to, yes, write.

I’m currently at work on what I hope is my tenth published book. I have easily that number of unpublished books. In some ways I’ve learned a lot and tend to think in big narrative, shaping material somewhat naturally (if you can call something earned over three decades “natural”) but in at least one very real way things are no different than when I was working on the three unpublished novels of my twenties. What remains the same is the fact that books don’t come into being through theory, through brainstorming, through gentle musing. Yes, all those things help and are necessary but the moment when something goes from a whimsical nothing into the beginning of a book is exactly the moment you start writing it. Not jotting ideas about it. Not considering point-of-view. Not wondering if a book about an amputee from Seattle who works with baboons will sell. And not writing another outline dear god.

Writing, daily effortful writing toward the goal of making a book, is quite different from any of those things. It requires pushing ahead and, if you keep pushing ahead on a daily basis, gaining the known scientific benefit of pushing: momentum. And then, if you are lucky, the problem becomes not that you can’t get going but that you can’t stop. Which means that everything else, things like work and eating and getting the taxes done and all the small things, too, things that you usually use as excuses, still get done but they get pushed far enough out of the way so that the big thing, the important thing, the book thing gets done first.

In some way I see this course as a corrective. The grad students I encounter these days are remarkably well-rounded, and are overall a lot healthier than I was as a young writer. In our program they don’t just take writing classes but they learn about publishing and become teachers and they work as editors on literary journals, and I support all this. With some students you can see them wisely thinking “I had better learn a trade,” because they see that even published writers can’t really make their living by just publishing books. I get it.

But I also believe that if you really want to become a writer, a great writer (let’s just say it out loud), then you ultimately can’t hedge your bets. Because being a writer has never been about logic, a plan, parental approval, sensible shoes. It has been and still is about wild risk and commitment. An illogical and crazy leap that everyone says you shouldn’t be taking. This was true before writing schools took over the planet and it’s still true now.

I am not saying you can’t be a good person, have a good job, balance the budget, all that. But I am saying that at some point if you really think this is for you then you’ve got to do it, got to take the wild gamble and put it all on red. “Boldness and commitment brought rewards.” Walter Jackson Bate said that in his bio of the young Keats. Boldness and commitment. Those are not part-time, hedged, sensible things. They are things that lead you places though the scary thing is you’ll have no idea where they’ll lead.

P.S. It wasn’t until I posted this that I realized I was plagiarizing an earlier Bad Advice by Bill.