David Gessner's Blog, page 22

February 1, 2015

Girlhood. (Supah Sunday Edition.)

First, our Massachusetts pals Matt and Ben help Bill and Dave explain Deflategate HERE.

Next, here are a couple of pics, seven years apart.

January 29, 2015

Celebrating Ed Abbey’s Birthday

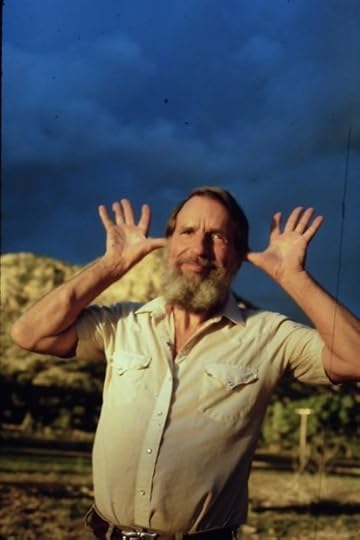

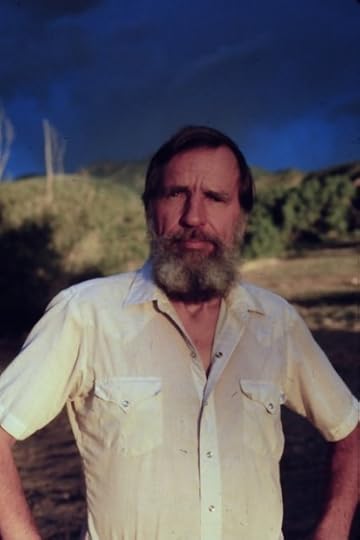

Photographs courtesy of Milo McCowan and Lyman Hafe

Today is Ed Abbey’s birthday and Orion magazine is helping celebrate by running both an article and a blog of mine, both excerpts from my forthcoming book, All the Wild that Remains: Edward Abbey, Wallace Stegner and the American West.

Here’s an excerpt of Orion’s blog excerpt to give you a taste:

It is a tricky business being an Ed Abbey fan these days. We shift toward uneasy ground. Because Abbey is no longer just a writer whose books you read; he is a literary cult figure who has followers. The skeptical reader recoils: “Oh, I don’t want to be part of that.” But clearly Abbey lives, at least in the West. Fresh off the press the same week I visited Ken was an article in the Mountain Gazette, a journal in which Abbey himself often published, in which M. John Fayhee, the editor, took no small delight in mocking the Abbey fandom: “They wore clothing that looked like what Abbey wore. They drove vehicles that would meet with Abbey’s approval. They tossed beer cans out of truck windows because Abbey did.” This hit a little close to home. I thought back to my days in Eldorado Springs and remembered the cans of refried beans I ate, part of the official Ed Abbey diet. I fear I was, unbeknownst to myself, a sort of groupie.

It is easy to mock the more rampant Abbeyites. But the tendency to attach ourselves to writers is a not entirely unhealthy thing. Fandom may be laughable but it has its purposes. Stegner wrote of Bernard DeVoto that “father hunting had almost been a career for him.” He meant that DeVoto sought out older writers, and was eager to sit at their knees. He did this with Robert Frost, whom he first believed was “living proof that genius could be sane,” but whom he eventually broke from with the words: “You’re a good poet, Robert. But you’re a bad man.” Stegner in turn would look to DeVoto as a model, a father of sorts, though a father with the wild streak of an adolescent son. It is easy to dismiss these relationships as mere hero worship, as Oedipal. But what underlies it is something better, I think. A hunger for models. For possibilities. For how to be in the world.

To read the whole blog click On the Tricky Business of Being an Ed Abbey Fan

To read the Orion article click on Edward Abbey’s FBI file.

To pre-order the book click on All the Wild That Remains.

I know that’s a lot of clicking. Apologies.

January 28, 2015

Bad Advice Wednesday: How to Get on a Roll, or, The Value of Momentum

I’m re-posting this, one of our very first “Bad Advice” blogs, since it goes with some things I’ve been saying in the “Just Write” class I’m teaching this term.

Momentum. I say the word so much in my classes that I wouldn’t blame students if they walked out or threw bricks. But I’ll say it again. Mo-men-tum. Sometimes it seems to me that the whole writing game–the whole of life?– is contained in that one word. How do you get in movement and stay in movement? The question. How to get rolling and, more importantly, keep rolling?

As for the “keep rolling” aspect (which, momentum being momentum, is the easier part) many people have tricks, usually some variant on Hemingway’s habit of stopping when you know what sentence you’re going to write next. That’s not for me. For one thing, if I know the sentence, I’ll write it down while I’ve got it. For another, it’s just too rational. “If I know what I’m doing I can’t do it,” said Joan Didion. That’s closer to it. Momentum, whether starting it or keeping it, is about the continued thrust into the unknown. The decision–if it even is a decision– to move forward without or beyond the aid of reason. Momentum is the march into darkness when your sensible (and fearful) side is telling you stay put in your clean, well-lighted brain.

But this is pretty vague. Let’s get specific.

1. You are sitting at your desk writing, or kind of writing. It isn’t going well. You started a long project, let’s call it a novel, a week ago and you are at an impasse. This morning your specific problem is that you need to get your main character, Elton, down to the farmers’ market where he can meet Lorrie, the cute single mom. But suddenly that idea seems kind of stupid. As does the whole book. Dark thoughts gather. How did you ever think that you, busy you, would have the time or energy to write a novel? Wouldn’t it be better to start next January when you’ll have more time? That sickly feeling comes over you, that everything-I-write-seems-lame feeling. Quitting looks more and more attractive. If not quitting the whole project, then at least for the day.

But you don’t. Not this time. Instead you somehow plow through those doubts and shove Elton into the car and get him driving down to the farmers’ market. You are typing now, though you are not initially freed from the curse of insecurity. You’re still pretty sure what you’re doing sucks but at least you’re doing it. So you keep moving, keep typing. Maybe in the back of your head you now remember that you don’t have to be in a chipper mood to write well, and that, while we all improve as writers, we also pretty much write the way we write, our sentences like our fingerprints, and this is semi-reassuring becase it means your sentences come out the way they come out independent of your feelings about them. And then Elton and Lorrie meet, and you like the description of her laugh (it isn’t half bad), and you have him say something witty and then she, with little effort from you, says something witty back and…..

….and what you are experiencing, whether you know it or not, is the writerly law of momentum. You are in motion and you might just stay in motion for a while. It doesn’t mean everything is perfect and that you will now write the whole novel is one great surge, like Dostoyevsky or something. But it might mean you will write for another hour or so. Tomorrow you might throw what you wrote away but tomorrow you might also feel a little different. A little more solid, a tad more confident. And, if you are lucky, you might develop a taste for this thing, this movement, this momentum, which might let you power through those doubts.

You understand, of course, that “power through” isn’t a very artistic or sophisticated term. But you are beginning to think it is an effective one. The thing is that this is how “rolls” often start. You have a crappy day but then you have a not-so-crappy day that leads to a very nice average day and then suddenly some part of you (maybe not your brain) realizes that you’ve had two not-so-bad days and then you have a good day and then, before you know it, you are feeling strangely confident…. You would jinx yourself by saying you are rolling. But you are.

2. What I described above is momentum on a small daily scale. But for writers there is also something else, something larger, that I will call career momentum. It involves, for most of us, the creation of a book, or, hopefully, of books.

2. What I described above is momentum on a small daily scale. But for writers there is also something else, something larger, that I will call career momentum. It involves, for most of us, the creation of a book, or, hopefully, of books.

For writers who are starting, or writers who are stuck, I always bringing up Keats and the composition of his long poem Endymion (I even drew a cartoon essay about it.)

The gist is that Keats, at the beginning of his very short career, young and clueless, decided that rather than “Sit on the shore and pipe on his flute and take tea and comfortable advice” would “dive into the sea and see where the shoals were.” How did he do this? He decided to put aside the short, cozy, and fashionable lyric poems he had been writing and set to writing a long epic poem. It did not go particularly well at first, but he—to use our new phrase—powered through, forcing himself to write a certain number of lines a day. Endymion is generally regarded as a somewhat weak poem, but from a psychological point of view it is fascinating. As Keats’ biographer, Walter Jackson Bate, has written, the real benefits came later, in the next poems, and in the lack of fear in front of a blank page, and in the readiness of phrase that, having trained himself in Endymion, came more easily. Bate quotes William James: “You learn to skate in the summer.”

I am not saying that all our books need to be slammed together. You may be an entirely different sort of writer, one who composes in your head, and comes to the page with a vision, and with precision. But for most of us, at some point, we need to put our perfect vision of a book on a shelf deep in the closet and get down to the work of writing. Most books need to be framed out, like house, and framing isn’t precision work. Better to get in movement now and stay in movement since, as Samuel Johnson said, activity is “self corrective.”

The strange thing is that once you are in movement, once you have momentum, you learn things you can never learn in theory. Your reasonable brain, for instance, might have ideas about plot, but it can’t know plot in a way someone who has wrestled with a book (or two) will. Likewise, you may have some general ideas about your own work habits but these are just ideas until they are tested in the fire of a book. Once you emerge from those fires, you suddenly know a lot more about yourself and are able to predict how you will respond, and, more specifically, practical things like how long it might take to finish a project or, at least, this chapter. (I am listening to Elvis Costello’s Greatest Hits as I type and “Every Day I Write the Book” just came on. Really, I swear. So I might as well go with the music and say that that’s another thing about momentum: once you get going you’re going to want to get that feeling every day. Day after day…rolling….The song’s over now—a song called “Shipbuilding” is on.)

One final thought on momentum. In skiing terms this might be more of black diamond tip, for experts only. When you are starting out there is much to be said for focusing your energies on completing one project, one book. But once you are rolling, once you have momentum on your side, there is nothing wrong with jumping around a bit, hopping from project to project. I read a recent interview with Cormac McCarthy where he said he was working on five books at once. Why not, if you can do it? It’s a different kind of momentum than “powering through,” the opposite of forcing, just going with the one that’s coming. There are real advantages to this sort of method. For one thing you are rarely stuck. Often when you are working on one project the solution to another pops up. It’s another one of those things that feel different when you’re inside it than it looks from the outside, in theory. From the outside it might seem overwhelming to have so many balls in the air, to be doing so much. But from the inside it can actually be a rejuvenating way of working. “A change is as good as a rest,” said Churchill, who knew a thing or two about variety. It allows you to “rest” certain projects while keeping an overall movement.

And movement, after all, is what it’s all about.

January 24, 2015

January 22, 2015

Sixty by Sixty: A Meditation in Mosaic Upon the Sixtieth Birthday of the Haystack School of Arts and Crafts, and My Own

Elysia at Haystack, 2013

Prologue (in Sixty Words, Too: One to Grow On)

This essay is about the power of collaboration. Written in my sixtieth year, it’s a mosaic of sixty juxtaposed sections, each of exactly sixty words, a total of 3,600 tesserae, or assorted bits. The multiples may be read in any order, inviting readerly collaboration. Please number the boxes as you go to create a fresh path for others to follow.

1. [ ]

I finished my own sixtieth year by serving as visiting artist at Haystack, which had recently itself turned sixty, and was aging better than I—such a lovely place, both eternally and in human time: rocks and mosses and mushrooms and shell beaches, also wind. Craft was at the heart of things, and craft, I came to see, is collaborative.

2. [ ]

At La Selva Biological Reserve in Costa Rica a decade ago, I was struck by the way the scientists I happened to be among worked together as well as apart. An idea might have an author, but an idea was owned by no one. Everyone was available to help chase the idea down, sometimes literally, as with the wild animals.

3. [ ]

As a literary writer, I have not been inclined to work collaboratively. In fact, as I came up through college and my long apprenticeship, the rather romantic vision I held onto was of a writer alone in his garret, or perhaps not quite alone (a muse was permissible), thinking brilliant thoughts and writing great sentences, neither to be messed with.

4. [ ]

Collaboration messes with the economy of competition, of course. It redistributes power from a top-down, winners-and-losers, production-first model to a steady-state, process-and-development model, one in which cooperation nurtures trust. Meanwhile, the sharing of materials, ideas, skills, techniques, tools, and spaces nurtures not dependence but freedom: the liberal and all-but-literal flow of ideas among creators, everyone an apprentice, everyone a master.

5. [ ]

I used to play in rock bands, and these were completely collaborative enterprises, four or five or six or more young people, artists all, all full of ideas, working together to produce one sound. It wasn’t always copacetic, of course, more like a series of group marriages, with group ambition not always in line with individual ambition, and quarrels common.

6. [ ]

As an apprentice writer, I had the idea that it was I against the world. I had read someplace that your relationship with your publisher was adversarial, you fighting for the purity of your ideas and your stories against the commercial instincts of the publishing world, a bunch of bloodsucking capitalists who would sell you for meat in a heartbeat.

7. [ ]

At night I’d go over to the fabulous Haystack library where I generally failed to get online. But one night a bunch of the wildlings from the glass studio were watching a documentary about Dale Chihuly, a record of his studio as he/they created one of his/their complicated ceilings, five or six craftspeople at work, “Chihuly” more than one person.

8. [ ]

In Costa Rica, a dendrologist might stand up at breakfast to ask our group how best to analyze the composition of the increasingly but varyingly acidic puddles that collected in the thousands of niches formed among the dazzling high roots of the strangler fig as it destroyed its host tree: a chemistry question in a research station devoted to biology.

9. [ ]

The ecologist sees the interconnectedness of all things. So does the Buddhist, though the Buddhist adds that nothing is real. And physicists are getting pretty close to agreeing, speaking of collaboration: Nothing is real. As the science proceeds, theoreticians in physics are working more and more with philosophy departments, who are working on many of the same questions, oddly enough.

10. [ ]

One question at Haystack was how to get a photo of the perfection a small spider had woven on a deck railing. I tried in varying light. Finally, after fog, a million droplets defined the orb-weaver’s work. Later, though, looking on my computer screen, I liked another shot better: a man-size spider seemingly clinging to the fab lab shingles: perspective.

11. [ ]

Did each damp strangler-fig niche constitute an ecosystem? If so, was the chemistry a trait of such an ecosystem or its result? A lively discussion ensued, a myriad of approaches (including some great comedy), approaches that considered the immediate problem but also related problems scientists had already solved, all ending in a plan of action and interested parties to help.

12. [ ]

The wood studio at Haystack hummed with machines and reminded me of high school wood shop, a favorite place. I liked the way Katie Hudnall was working alongside her students, and how all of them were working on boxes of various kinds, sharing materials, tools, ideas, and also conventions, all those ways people had worked with wood in the past.

13. [ ]

Herbert Hoover’s “rugged individualism” wasn’t only a campaign slogan but a source of national pride. Kind of oxymoronic: How can there be a nation if there are only individuals? Self-sufficiency, self-reliance, personal independence, these are all myths, very American. You can only pretend you built your business alone, for example. But don’t point this out if you’re running for president.

14. [ ]

We watched leaf-cutter ants for hours, trying to answer questions we’d come up with as we thought about how to teach science and science writing in the rain forest. The amazing ants used leaf fragments to grow a particular mold, which was their food. But we would have needed a lot more time to figure that out, and more people.

15. [ ]

Consider sports! We applaud individual effort and ability, naturally. But there isn’t any one soul who could play against the Red Sox and win. Well, maybe some years. How does this work? The star player has his abilities and motives and goals, and these align with those of the team. But how do we know when we’re on a team?

16. [ ]

Recently, in a fairly rough saloon, a gang of brave moms took over the pool table on a win and announced that 8-Ball was over. Instead, they introduced Save the Whales (which they’d named after a cooperative board game of the 1970s), inventing noncompetitive rules as they went, funny. But profound, too: “I play the winner!” meant nothing after that.

17. [ ]

When is working together truly collaboration, and when is it merely employment? People must be equals to collaborate, no? If not equals in talent (always there’s going to be an imbalance), then in contribution. But what does that mean? We put in the same hours, and therefore we’re equal? No, it’s something other than time, and something other than power.

18. [ ]

At Haystack I ran a writing group on the deck by the writing studio every afternoon, bright sunshine. People from every studio took part at one time or another, and a small core group attended every session. I tried out different themes each day, from journals to maps, from good cop/bad cop to monologues. And we shared, laughter and tears.

19. [ ]

Mosses: pincushion, nothing else to call it, well, except for Leucobryum glaucum, a tight mound of green—soft, fuzzy, irresistible. And sphagnum, stringy and peaty, deep in pocket bogs among boulders, likely multiple species (there are 120 worldwide, just a few in Maine, and fewer on the islands). Schreber’s moss is most common (Pleurozium schreberi), feathery, a little red beneath.

20. [ ]

A chemist back home had given one of the La Selva scientists a collection kit for a very different investigation of soils, one she was no longer pursuing, and so she went back to her bunk to retrieve the kit, made the dendrologist an offering: a thousand vials in a nifty to go case with labels and lids and seals.

21. [ ]

In the metals studio, someone has painted a lobster on the first-aid box. Bob Ebendorf offers a lesson on curling wire, and curls make their way through the work, pieces of great variance but with the history of jewelry and metalsmithing (and human fascination with objects) in common, and words: sentence fragments, whole quotations, single exclamations. “Fear,” said one earring.

22. [ ]

As part of the Haystack experience, I took a class. Terrified, I chose Robert Johnson’s nature journaling. I had always been told I couldn’t paint. Robert said, “Of course you can.” He is courtly, avuncular, a little older than I, and so I believed him. First day he set me up with a painting kit: brushes, pencil, palette, paper, watercolors.

23. [ ]

In 2001, I wrote a long story called “Big Bend.” The Atlantic cut it in half. I found the cuts added power. Then, in my collection Big Bend, back to the original length: more depth. The NPR program Selected Shorts scripted an intermediate length for performance by James Cromwell at the Getty Center. He asked me onstage if I minded!

24. [ ]

I told my group about Rudy Burckhardt, the great, obscure, and always solo filmmaker. I was overawed, Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, 1998. But he was kindly, asked me, “What have you been thinking about?” A good question that brooked no small talk. The next month, on his eighty-fifth birthday, he drowned himself in his pond, a long-planned suicide.

25. [ ]

In workshop, Robert said he’d been trying to get text into his paintings. And then he asked me to say something about writing and painting: collaborative teaching. I remembered Gauguin’s woodcarvings—I’d seen them in the old Jeu de Paume museum in Paris—the entryway to his Tahitian hut. “soyez mysterieuses,” the impressionist had carved over floating nudes: Be Mysterious.

26. [ ]

A conceptual artist (whose name I have misplaced) once wrote political slogans on leaves in a controlled environment, and left these for her colony of leafcutter ants to find, cut up, and carry. Instant protest march! Also an example of a human working with animals. To different ends, it’s true, so not exactly collaboration, but a window on group mind.

27. [ ]

Looking into the concept of ant mind, I read some of myrmecologist Edward O. Wilson’s very accessible (and sometimes controversial) work. He thinks ant colonies shed light on the human condition, for one thing: An ant colony is a kind of brain. Also fun facts: All the ants in the world weigh more than all the people in the world.

28. [ ]

Robert joined my group as well. One afternoon we talked about journals. He said he loved aimlessly to write after the painting day. Writing brought him down from the stresses of the work, helped him process his vision, assess. I said that I can’t stand to write in a journal—I write all day! He said, “Then you should paint!”

29. [ ]

The question ants help answer is: Why altruism? Why would an individual sacrifice herself for the good of another? And why would natural selection pass such a trait along? Our self-centered aspects are only human: greed, violence, aggression. They are tempered by (and most religions extol): sharing, compassion, cooperation. Survival of the group assures survival of the individual. Self-sacrifice works.

30. [ ]

Wilson launches his book The Social Conquest of Earth with three questions: “Who are we? Where did we come from? Where are we going?” He knows these are the questions, disordered, that Paul Gauguin wrote in the upper right corner of his famous Tahitian painting of the stages of human life: “D’où venons nous? Que sommes nous? Où allons nous?”

31. [ ]

We join groups to protect the self, to take advantage of the skills and abilities of others, to offer our own. Inside the group, of course, there are subgroups—humanity divided, and then divided again and again. And these groups within groups may take on the self-centered traits of individuals along with the altruistic traits, become nearly human in themselves.

32. [ ]

The staff ornithologist wanted to talk about light, the varying access to light at various positions in the strangler’s root niches. A totally separate problem (some dismissive noises around the room over rice and beans—still only breakfast!), but as he spoke the relevance came clearer, also the amount of work that relevance would take to properly study and acknowledge.

33. [ ]

Suddenly, a knot of grad students took it upon themselves to unpack a spectrometer no one had known what to do with, and (eschewing siesta!) marched off into the forest to make some tests no one knew what would come of. Even I took part—I could ask questions as well as anyone (though never come up with the answers).

34. [ ]

I attended La Selva to take a course for professors: how to bring a college group to Costa Rica and how and what to teach once you got there. I was the odd person out, a writer, and not a science writer, either, though something of a naturalist. I felt insecure, but slowly realized I had something to offer: words.

35. [ ]

My friend the biologist (and science writer) Drew Barton had suggested we take the course together and then later team teach our own rain forest course, something about writing and science in Costa Rica. How would we work together, and how would we work apart? Of course, field journals would be part of the equation: observation, writing, drawing. Experiments, too.

36. [ ]

Ferns: Sensitive—these already looking pretty moribund midsummer, stressed by salt and cool temperatures, with last year’s fertile fronds brown among them. Christmas—these stay green the winter through. Wood—small and feathery, elegant, leaves cut thrice. Bracken—grows in poor soil as at the edge of old dunes. Interrupted—fertile portions in the middle wither and give the name.

37. [ ]

Things we drew in Robert’s class (pencil and color notes on field trips, then paint back in the studio): mussels, clams, lobsters, crabs; rockweed and wrack; boulders; shorelines; islands distant, islands close; cones from hemlock, fir, spruce, and larch; mosses, lichens, mushrooms, molds; rare wood lilies, fireweed, dandelions, phlox; grasses and sedges; gooseberries, baneberries red and white (called doll’s eyes).

38. [ ]

Things we wrote on our drawings: “Negative space gets motion of waves.” “I have a headache and Robert won’t stop talking.” “Cobalt Blue plus Cadmium Red Light.” “Woman walks by, shouts, ‘those people are painting, shhhh.’” “Barred Island in fog, I think.” “Edgar M. Tennis Preserve on Sunshine Road. Basement hole with lilacs.” “Water green, not blue, with Payne’s gray.”

39. [ ]

In Robert’s studio, we gave a card to our studio assistant. Robert painted it especially, depicting several of the objects we’d all been studying, drawing. The “committee” asked me to write a few words on the card. I did, a note of thanks running behind Robert’s painting such that you couldn’t quite read it, but had to intuit the love.

40. [ ]

One afternoon at La Selva, the herpetologist asked whether anyone had any snakes to report. Everyone did! Mine had been in the shower stall that very morning, a rat snake of real girth and not much length. The herpetologist listened closely to all the stories—there was information to be gleaned from our subjective experiences: descriptions, locations, numbers, positions, times.

41. [ ]

In a nonfiction workshop I taught at Haystack 2011, we writers found we were jealous of the folks in the other studios, what with their workbenches and tools. They made stuff. My point was that we made stuff, too. But someone suggested we should really come up with an item of some kind to put in the auction. But what?

42. [ ]

Kaya Lovestrand, summer intern 2013, had taken a course in mosses and accompanied us on one of our drawing trips—Barred Island—to help us identify a few common types, but also to observe some major generic divisions. We collected samples (Robert’s kit includes a collecting box) and brought them back to the studio. Naming is knowing; drawing is seeing.

43. [ ]

The herpetologist was making a snake census. Much of the work had to be done at night, when the snakes were active. He needed people to help. We met at ten p.m. and stayed out most of the night, headlamps, flashlights, eyeshine (or as he called it, tapetum lucidum). The forest was staring back: frogs, spiders, mammals, owls, and snakes.

44. [ ]

“Never put your foot down without looking,” the snake man said. And: “Look up! Look down.” Five of us huddled close behind him, hours into the night, thirty snakes to report. A lash viper hanging at face level over the path. My face. A fer-de-lance standing its ground: mortal danger. Coral snake, bird snake, rat snake, false coral, black snake.

45. [ ]

More eyes meant more chances to spot reptiles. We crossed over the Puerto Viejo River on a high, rickety footbridge. I held the railings, enjoyed the swaying. Our fearless leader looked back. “Hands off the railings,” he hissed. And shined his light under there, where, casting long shadows, and only a few steps ahead of me, four fat scorpions lurked.

46. [ ]

In the ceramics studio, Bonnie Seeman had clay on her cheek from putting her forefinger there to think. So many questions. Her wisdom channeled down from millennia: “In north India there was a tradition …” And by way of the ancestors she solved the problem at hand. I loved the sounds of kiln night, cheers when the door opened, treasure.

47. [ ]

My favorite Burckhardt film starts with five minutes of rapid-fire images: people in motion, zooming cars, buildings glinting. It’s jazz for the eyes, pure rhythm. Then a protracted vista, Brookyn from Manhattan. Seemingly static, until we notice a crow. It enters left, flies all the way right, five full minutes. Then bang, the images from the street flash again, lightning.

48. [ ]

As a writer, I’m jealous of visual and functional artists: Working with your hands, there are plenty of repetitive tasks that leave mind space to listen to music, say, or to have a conversation. At Haystack, I roamed from studio to studio and took part in these conversations, which were only partly about making art, and partly were the art.

49. [ ]

Lisa Cirando brought a beautiful, bluey paper she’d made earlier. What might our nonfiction class do with it? Words were our medium! We were craftspeople! We all contributed a phrase, something from our sessions. Mine was “Just write!” At the fab lab, several volunteers laser cut those phrases, making negative space. Backlit in a window? Gorgeous, a message of cooperation.

50. [ ]

Over 100 people were at the third summer session 2013, including staff, instructors, and participants. I crossed paths with each, one way or the other, and each embodied an idea. I had the feeling that as in outer space each body exerted gravitational pull, some pronounced, some so subtle you wouldn’t know till later you’d been pulled out of orbit.

51. [ ]

The glass studio roared late into the night, the furnaces blasting. Always from there came music and shouting and laughter, a bunch of devils playing with fire. Joe Grant led with such a generous, annealing spirit—you can’t work glass alone, not really. The students worked in pairs, one to turn the rod, another to shape the object being born.

52. [ ]

Family is the essential collaboration, and a fine perquisite for the visiting artist at Haystack is that family can join in. My daughter, Elysia, who had not yet turned 13, took part in Sonia Clark’s multiples workshop in the fiber studio. My wife, Juliet, joined them. Sonia was very warm, made sure they had supplies, and soon the multiples multiplied.

53. [ ]

Each studio has a personality, the sum of the attitudes and moods of the people who happen to be in the room (perhaps especially the instructors), but also an essential expression of the type of work being engaged. Glass was boisterous. Wood was practical. Fab lab, intellectual. Metals, on task. Fiber, cheerful, even hilarious. Clay, determined, elbows out. Drawing, contemplative.

54. [ ]

Back from the rain forest, I found that tapetum lucidum had burned its way into my brain. When the peepers started that spring, I realized I’d never seen one. I texted Drew, simple as that, and soon, equipped with headlamps and flashlights and three or four kids, we made a night expedition, found eyeshine: six species of frogs and toads.

55. [ ]

Robert had us create our own names for mushrooms. Difficult, as some of us already knew the real names. But a Fly Agaric, bright red with white spots, became a Sore Throat. Others had similarly suggestive names: Slimy Butter, Elf Shelf, Snot Blob, Many Tongues. The result was a group language that expressed a new way of thinking and seeing.

56. [ ]

I didn’t hear frogs at Haystack, but perhaps the wind and the waves obscured such sounds. I suggested an eyeshine walk, and come night twelve of us from various studios were padding down Haystack Lane, flashing lights into the quiet woods. No frogs, but lots of eyeshine: spiders. And balsam pitch drips, orange. Finally, big green eyes, looming, a mystery.

57. [ ]

Marijo Simpson, fiber, collected rocks (more multiples) and placed a selection outside their barn door with an invitation to take one, alter it, put it back. And in the secret hours of ensuing days and nights, rocks disappeared. Then reappeared: jewelry attached, tiny clothing, googly eyes, a glass blob. That last was mine, but I couldn’t have done it alone.

58. [ ]

The ants accomplish the perpetuation of their colonies, and therefore of their types and subtypes. Individuals work together, each with a job, and no one ant sees the greater picture. Perhaps we don’t either. Our contribution to the colony may not even be something we recognize, but instead some subtle pull that grows from all the gravity we have encountered.

59. [ ]

Between two people, a power arises that is more than either person, perhaps forming a person in itself, one that combines traits: education, prejudices, loves, aesthetics. Among three people, two powers arise for each—that makes six—and then one more for all. Imagine the powers arising from a hundred people, and imagine those powers mounting the steps at Haystack!

60. [ ]

And then there’s the food, the beautiful dining hall, the ever-shifting dynamics of family-style eating, view of the ocean (or hot sun on your back). Stuart makes an announcement and the hubbub commences: every calorie an idea in the making. The powers shift about the room, one rising, one sitting, new relationships, fresh possibilities: What have you been thinking about?

[For information about the incredible opportunities at Haystack for writing and other craft workshops, have a look at the Haystack Website. This essay was written as part of my duties as writer-in-residence at Haystack in July, 2013, and published as a monograph by the organization. Contact them as above for a paper copy, and to make a donation!]

January 21, 2015

Bad Advice Wednesday: Fight Through the Fear

As I mentioned a couple of weeks ago, I’m teaching a graduate class this spring called “Just Write,” the idea being to clear away clutter and get down to the business of actually writing.

As I mentioned a couple of weeks ago, I’m teaching a graduate class this spring called “Just Write,” the idea being to clear away clutter and get down to the business of actually writing.

Last week, during our first class, I mentioned the “Christmas morning feeling” that early morning feeling writers sometimes get, when they go to sleep early thinking about the next day’s work and wake up excited to get to it. (I think I plagiarized, or half-plagiarized, that phrase from Donald Hall’s great book, Life Work.)

Well, suffice it to say, not every morning is Christmas morning. Over the last week I have woken up with a feeling not of excitement but dread. I suppose I could pin actual reasons on that feeling (an operation on my leg, anxiety about my forthcoming book) but it feels more free-floating than that. That creepy something-bad-is-going-to-happen uneasiness. Or, to put it more simply: fear.

I still go about my morning routine, stretch my back, feed the animals, boil tea, make coffee, and the rest. But I don’t quite sprint up to the computer as if it’s a present to open. I’m a little scared of turning on the machine, really. I worry that I don’t have the energy to deal with the bad that is coming or to make the things that I need to make. I think too much.

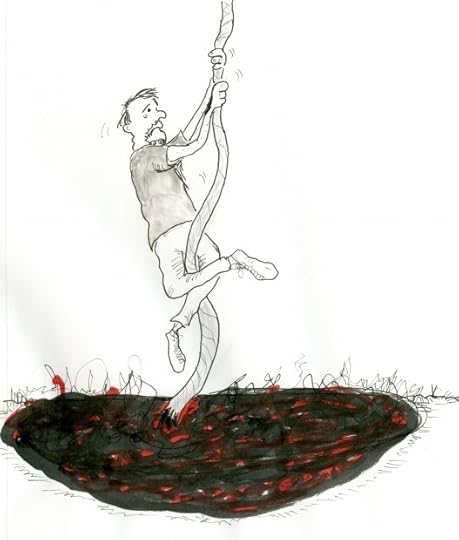

But generally, thanks to years of habit and, more importantly, the knowledge that if I let the fear paralyze me I will be on the fast road to depression, I start to type. Not always, and certainly not always well. But enough so that often enough that activity, combined with the magical alchemy of caffeine, becomes the self-made rope by which I climb out of the abyss.

I write this out from very recent personal experience. From this morning in fact. Two hours ago I was sitting here quaking, if not on the outside than in. The first strand of the rope was woven out of yesterday’s post on Wallace Stegner and largeness. This is the next strand. And now that I have some momentum I think that I will turn to an environmental post about something I saw while down in the Gulf a couple of weeks ago. Three strands will make for a pretty good morning, a way to pull myself up.

Though no guarantee that the fear won’t be back tomorrow.

(Sorry: that last line is not very pep-talky.)

January 20, 2015

Wallace Stegner on Largeness

I’ve spent a lot of time over the last few years in the company, or at least with the mind and words, of Wallace Stegner. It has been a bracing experience. One thing I’ve noticed about his thinking is that there is always a movement toward the general, an imperative to think more broadly and openly, a preference for the long view over the short, the large over the small. This was not just an intellectual commitment, but a spiritual, or at least a personal, one. “Largeness is a lifelong matter,” he once said. The goal was (and is) magnanimity.

I’ve spent a lot of time over the last few years in the company, or at least with the mind and words, of Wallace Stegner. It has been a bracing experience. One thing I’ve noticed about his thinking is that there is always a movement toward the general, an imperative to think more broadly and openly, a preference for the long view over the short, the large over the small. This was not just an intellectual commitment, but a spiritual, or at least a personal, one. “Largeness is a lifelong matter,” he once said. The goal was (and is) magnanimity.

The “largeness” quote is contained and given context below by Stegner’s answer to this interview question: Should the teacher, in the process of instruction, consciously try to shape a student’s personality or enlarge him or her as a human being?

Here’s his reply:

Well, I have some fairly strong feelings about that. I do not believe I can teach anybody to be a bigger or better or more humane person. But I do subscribe to the notion that, in order to write a great poem one should be, in some sense or another, a great poet. This suggests that any writer had better be concerned with the development of his personality and his character.

I don’t believe, with Oscar Wilde, that the fact that a man is a poisoner has nothing to do with his prose. It does have something to do with his prose. A poisoner will write a poisoner’s prose, however beautiful. Even if it has nothing to do with his private life, personal morality, or his general ethical character, being a poisoner suggests a flaw somewhere—in the sensibility or humanity or compassion or the largeness of mind—that is going to reflect itself in the prose.

Most artists are flawed; but they probably ought to make an effort not to be. But how do you teach people to enlarge themselves in order to enlarge their writing? It is a little like asking them to “commit experience” for literary puprposes.

Largeness is a lifelong matter—sometimes a conscious goal, sometimes not. You enlarge yourself because that is the kind of individual you are. You grow because you are not content not to. You are like a beaver that chews constantly because if it doesn’t its teeth grow long and lock. You grow because you are a grower: you’re large because you can’t stand to be small.

If you are a grower and a writer as well, your writing should get better and larger and wiser. But how you teach that, the Lord knows.

I guess you can suggest the ideal of it, the idea that it is a good thing to be large and magnanimous and wise, that it is a better goal in life than pleasure and money and fame. By comparison, it seems to me, fame and money, and probably fame as well, are contemptible goals.

I would go as far as to say that to a class. But not all the class would believe me.

This interview, and a whole lot else can be found, in Wallace Stegner’s On Teaching and Writing Fiction.

Click HERE to see my article in Orion on Edward Abbey’s FBI file.

All the Wild That Remains: Edward Abbey, Wallace Stegner, and the American West is coming out in April. “Two extraordinary men, and one remarkable book. To understand how we understand the natural world, you need to read this book.” –Bill McKibben

January 14, 2015

Bad Advice Wednesday Expands to Bigger Markets

Our new column!

A chance find in my daughter’s GIRL’S LIFE magazine…

January 12, 2015

Lundgren’s Lounge: “Preparation for the Next Life,” by Atticus Lish

Atticus Lish

The Great American Novel has always been a story about outsiders, people peering in through the gates at a uniquely American dream that seems maddeningly just beyond their reach… from Huck (where it all began), to the Joads and Gatsby and Bigger Thomas and on to McMurphy and Seymour (Swede) Levov, Ignatius J. Reilly and Sethe… these are all characters in pursuit of a mirage shimmering on an ever-receding horizon.

So what does the GAN look like in the post 9/11 world? Who are the outsiders that walk among us today, invisible and striving to be seen, to be recognized and validated as real? I offer for consideration Atticus Lish’s powerful debut novel, Preparation for the Next Life and his two indelibly sketched protagonists: Zou Lei, an illegal immigrant from northwest China and Skinner, a damaged survivor of America’s disastrous military adventure in Iraq. The trajectory of their meeting seems inevitable, driven by a propulsive, relentless narrative. They share an aching sense of loneliness that maybe, the author hints, might be assuaged by their coming together.

At first glance Skinner would appear better equipped to grapple with his situation, but it is Zou Lei who becomes caretaker as the couple embark upon a thoroughly contemporary American love story. What they have in common is a passion for the release of physical exercise and they pursue this with a ferocity that energizes the story. Though initially their physical pursuits are solitary, Zou Lei as a runner and Skinner as a weight-lifter, their story gains traction when they begin to run together through the boroughs of Manhattan, mostly Queens, or hit the gym where Skinner spots for Zhou Lei while teaching her the rudiments of lifting.

At first glance Skinner would appear better equipped to grapple with his situation, but it is Zou Lei who becomes caretaker as the couple embark upon a thoroughly contemporary American love story. What they have in common is a passion for the release of physical exercise and they pursue this with a ferocity that energizes the story. Though initially their physical pursuits are solitary, Zou Lei as a runner and Skinner as a weight-lifter, their story gains traction when they begin to run together through the boroughs of Manhattan, mostly Queens, or hit the gym where Skinner spots for Zhou Lei while teaching her the rudiments of lifting.

Interestingly this novel might have disappeared into the stacks of forgotten remainders if not for a fortuitous review. Published by a small press (Tyrant Books), with a conservative initial print run, Preparation for the Next Life began to gain traction when Dwight Garner pronounced it, “Perhaps the finest and most unsentimental love story of the new decade” in the NY Times. Aided by word of mouth from appreciative readers, the book became temporarily unavailable as the publisher rushed to print more copies, in a reaffirmation of the power of the reading community and the essential role played by “curators”… this despite Jeff Bezos‘ inchoate screeds decrying the Times and mainstream book reviewers and publishers as “gatekeepers” that prevent people from reading what they wish.

Another reader/reviewer wrote, “Now that America and the novel are dead, I hope we can have more great American novels as alive as this one.” Dead or simply reimagined? This marvelous novel is the strongest argument for the latter that one might hope for.

[Bill Lundgren is a writer and blogger, also a bookseller at Longfellow Books in Portland, Maine (“A Fiercely Independent Community Bookstore”). He keeps a bird named Ruby, and teaches at Southern Maine Community College.]

January 10, 2015

Getting Outside Saturday: A Few More From the Gulf

Birds and rig on Elmer’s Island, LA.

This photo and one below by Erik Johnson. All the rest by Mark Honerkamp.

An oiled herring gull.

Oyster shells in Bayou La Batre.

West end beach on Dauphin Island.