David Gessner's Blog, page 20

March 23, 2015

On the Road (and Writing the Book)

Here are some photos from the road trip that became my new book. Some are repeats that I published here during from the summer of 2012, but some are new. This is the first of two posts of pics.

First stop on way west: the home of Wendell and Tanya Berry in Kentucky.

The next day in Lexington with Erik Reece and Ed McClanahan. Ed was not just a Stegner fellow and a Merry Prankster, but was WS’s officemate.

Up Flagstaff (barely) with Rob Bleiberg and Chris Brooks. Abbey would have mocked us, Stegner ignored.

Rest stop at the top of the world. Adam Petry’s cabin above Paonia, Colorado.

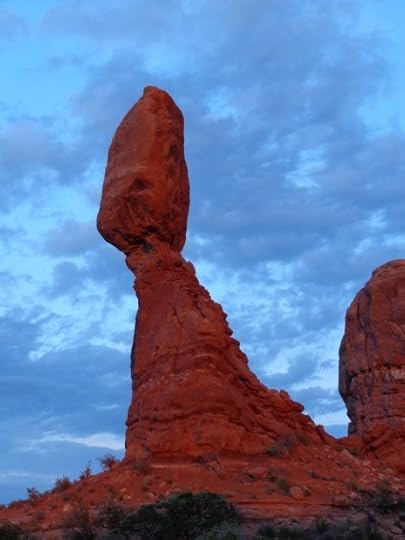

The requisite Arches pilgrimage. Some good light at Balanced Rock.

My protected campsite at Hamburger Rock (didn’t descend to usual spot by Indian Creek due to lightning, and flooding.)

The view.

Chatting with Ken Sleight, aka Seldom Seen Smith, in his office.

North to Vernal, Utah.

Bruce Gordon of Ecoflight, who showed me the gaslands from above.

The view from up there.

Back in Colorado at end of Harpers Corner trail in Dinosaur National monument. Looking down at the land that Stegner helped save.

My trusty steed in Park City.

At the Stegner graves in Salt Lake (courtesy of Stepehn Trimble.) Unlike in WS’s fiction, here there is no redemptive headstone for his father.

With Ken Sanders at Ken Sanders Rare Books in SLC.

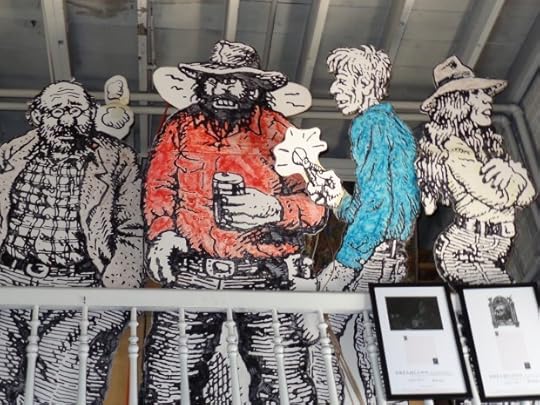

R. Crumb’s lifesize Monkey Wrench caricatures in Ken Sanders Rare Books.

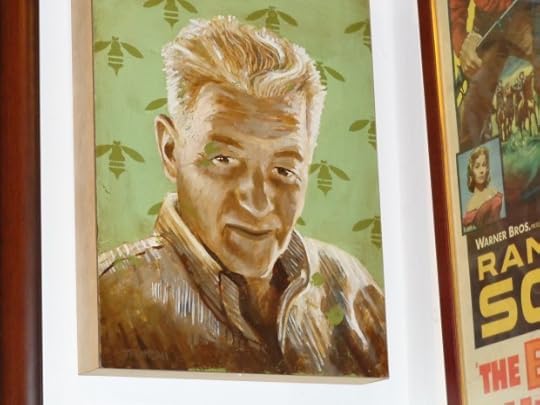

WS portrait on wall of KSRB.

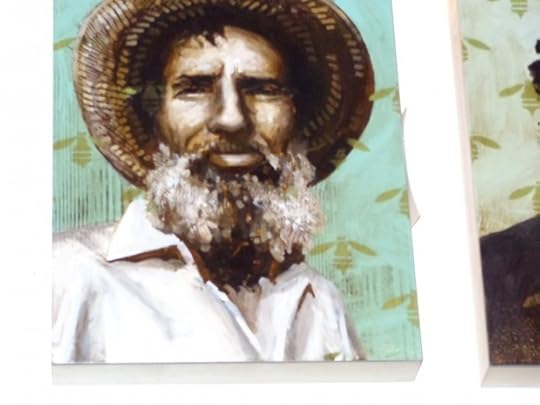

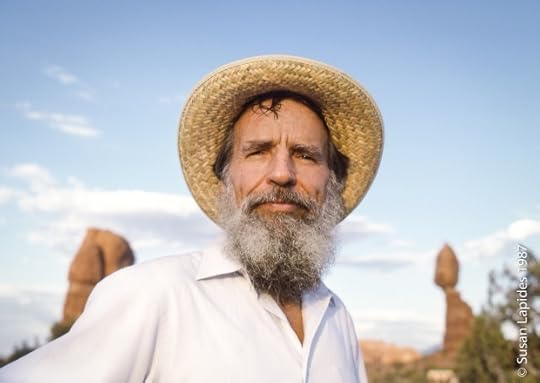

Portrait of EA on wall of KSRB based on photo by Susan Lapides.

The original Lapides photo of Abbey. All rights belong to Susan Lapides.

For more great Lapides photos click HERE

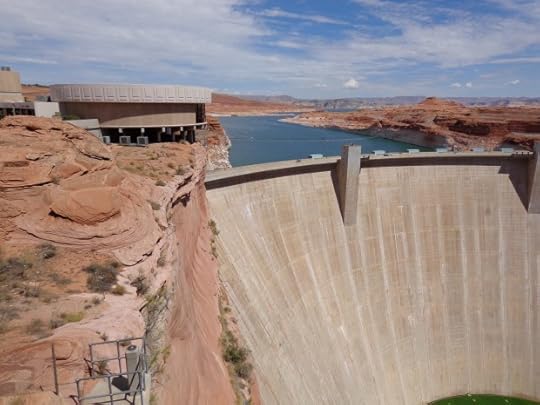

South to Lake Powell and the “damned dam.”

Down the San Juan with Greg and Hones.

The river crew.

To be continued…..

March 21, 2015

Getting Outside Saturday: Traveling Giants

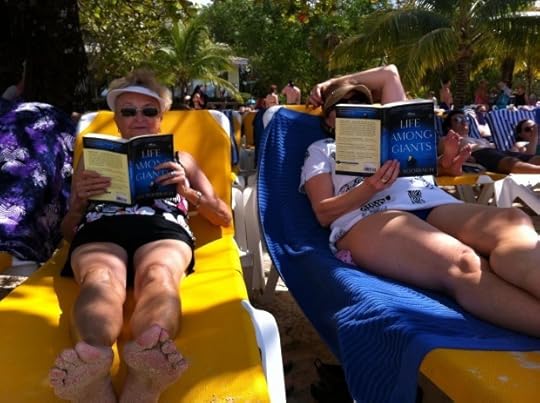

A friend spotted this scene on a recent trip to Honduras…

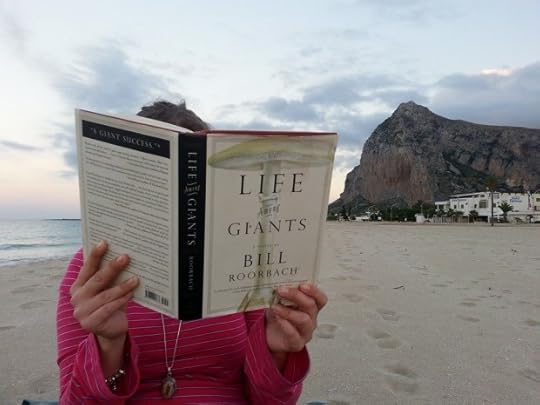

And here, a beach in Sicily–by Ross Nolan:

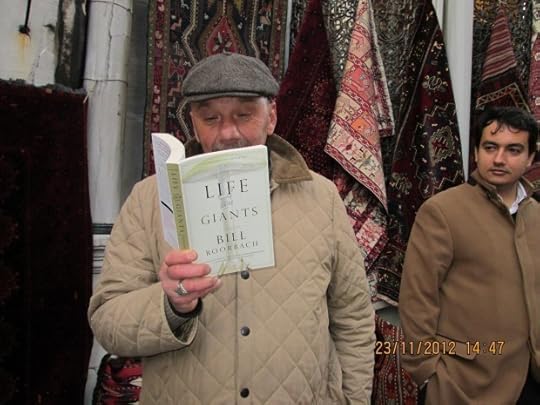

And this last one is outside the Grand Bazaar in Istanbul–caught by Pat Shipley in 2012–that’s an ARC, WTF?

March 20, 2015

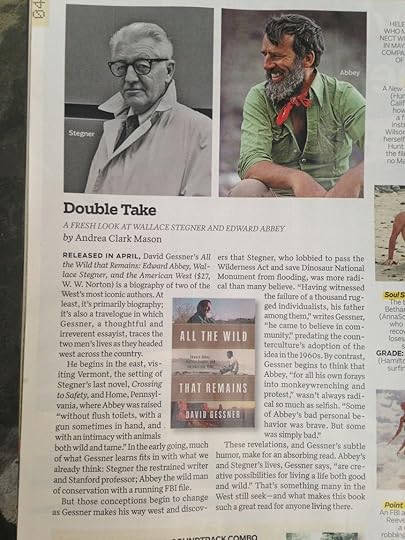

Outside Magazine Weighs in on All the Wild That Remains

This hit the newsstands this week. And the book is starting to ship! Let me know who is the first to get it.

March 17, 2015

March 10, 2015

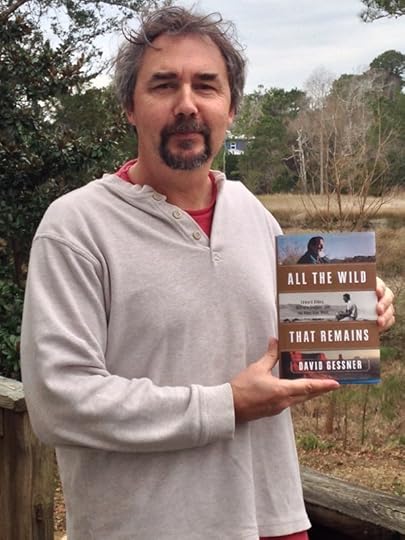

Book in hand

When the thing finally arrives. Always a nice moment.

As coincidence would have it, I just happened to be working on a memoir about Ultimate Frsibee that ends with my first book arriving. Here is the passage about receiving that first book:

The package arrived in the mail in March of 1997, the year I stopped playing Ultimate.

It came in a simple UPS box and even though I knew what was inside the box I didn’t think it would affect me like it did. This was no big deal after all. Being on the cover of the New York Times, winning some big prize, having your face on the cover of a magazine. Those were the things that real writers were supposed to glory in. Not this.

And it wasn’t a surge of glory that I felt as I unwrapped the package and looked down at my first book. Hones had taken the cover picture, a beautiful beach scene of some birds over the sand flats in Brewster. (I didn’t think it wise to tell the publishers that he had been tripping, as had I, when he took the photo.) I held the book in my hand and felt something profound rise up inside me. It was not the blood lust of a Frisbee conqueror spiking a disk on the field, or the exhilaration I would feel at the birth of my daughter. It was something much quieter. Something calmer and deeply satisfying. My face flushed with pleasure. I had the sense that I had finally accomplished something, something that it seemed I had been trying to accomplish forever.

But, then again, at the same time I had the opposite sensation. The sense, not of finality and achievement but of promise. The feeling that, after many false starts and much stumbling, I had at long last begun.

March 9, 2015

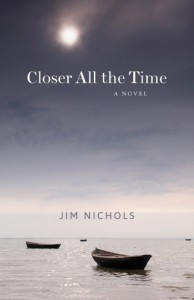

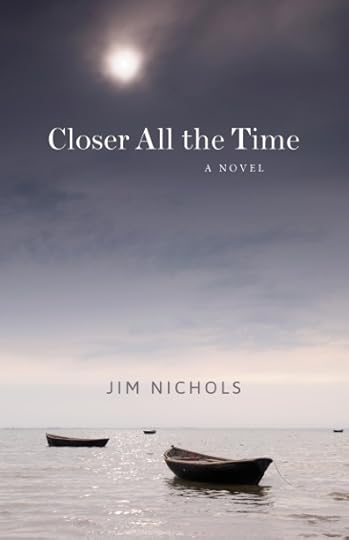

Lundgren’s Lounge: “Closer All the Time,” by Jim Nichols

JIm Nichols

Any discussion of candidates for the title ‘Fiction Laureate of Maine’ will quickly conjure names of the usual subjects: Stephen King, Elizabeth Strout, Carolyn Chute and Rick Russo spring to mind and all of them have carved out a unique niche in the Maine literary landscape. Bur for my money, when it comes to capturing the ethos of the people and culture of the Pine Tree State, perhaps no one does it better than Jim Nichols.

Nichols’ latest novel, Closer All the Time (Islandport Press), is a lovingly rendered series of connected vignettes centering on the fictional coastal Maine community of Baxter. And although the author’s insights clearly mark him as a member of the clan, he does not shy away from depicting the sometimes dark underside of small-town life in Maine: the petty feuds that endure for generations, the xenophobia masquerading as rugged individualism and the tensions between “natives’ and newly arrived people with lots of money and little sense of decorum regarding the way that things have always been done.

One of the early stories, all of which are named after the character at the heart of the action, is “Early,” about a recent widower struggling to extricate himself from the emotional void left behind after his beloved Evangeline passes away. Early (so named for his propensity to be the first one out on the flats each morning), rouses himself to get up and explore some off-limits clamming grounds, legality be damned. Running into a younger acquaintance, the two set to work rhythmically raking the flats and it is here, in his description of the work, that Nichols’ writing prowess is on full display. I have never raked a clam flat in my life, yet there is an undeniable verisimilitude to Nichols’ description that will put any reader right beside the two men, united in their work and the adrenaline rush of doing something outside the bounds of the law. Of course things do not go as planned, as such escapades often do not: chased by the clam cops, Early and his young friend are forced to jettison their catch and barely escape being caught. But in the end, bereft of clams, it is clear that Early has finally begun to begun to lift himself out of the grief and depression that had been threatening to swallow his life..

One of the early stories, all of which are named after the character at the heart of the action, is “Early,” about a recent widower struggling to extricate himself from the emotional void left behind after his beloved Evangeline passes away. Early (so named for his propensity to be the first one out on the flats each morning), rouses himself to get up and explore some off-limits clamming grounds, legality be damned. Running into a younger acquaintance, the two set to work rhythmically raking the flats and it is here, in his description of the work, that Nichols’ writing prowess is on full display. I have never raked a clam flat in my life, yet there is an undeniable verisimilitude to Nichols’ description that will put any reader right beside the two men, united in their work and the adrenaline rush of doing something outside the bounds of the law. Of course things do not go as planned, as such escapades often do not: chased by the clam cops, Early and his young friend are forced to jettison their catch and barely escape being caught. But in the end, bereft of clams, it is clear that Early has finally begun to begun to lift himself out of the grief and depression that had been threatening to swallow his life..

The rest of the stories follow a chronological progression, focusing upon the youth of the village, then the tender infatuations of adolescence and the heartbreak of the loves and challenges of grown-up life. The soul of this indelible collection is Baxter, which could be almost any small community, anywhere, a place where the inhabitants scrape and struggle and try to understand why. Nichols makes it clear that despite the travails and the confusion, there is always a tendril of hope that most often connects back to the community.

There will be a reading and book signing to mark the release of Closer All the Time at Bayside Bowl, 58 Alder St. in Portland, Maine, this upcoming Tuesday, March 10th from 5 till 7. If you’re anywhere near, please come join us for a celebration of the author’s work and the rich literary scene here in Maine.

[Bill Lundgren is a writer and blogger, also a bookseller at Longfellow Books in Portland, Maine (“A Fiercely Independent Community Bookstore”). He keeps a bird named Ruby, and teaches at Southern Maine Community College.]

March 5, 2015

Table For Two: An Interview with Jim Nichols

Debora: Jim it’s lovely to have you with us at Bill and Dave’s Cocktail Hour. Congratulations on your new novel Closer All the Time, published by Islandport Press, available now—and at last, for established Jim Nichols fans! I’m a newcomer, Jim, and wish to say that I love this book for the tenderness in the writing and the expressiveness of the characters. It’s clear that there is a lot of experience and wisdom behind these pages.

Jim: Hi Debora, it’s a pleasure to discuss CATT with you and to be part of Bill & Dave’s…one of my very favorite literary sites. And thanks for the kind words, I’m really happy you enjoyed the book.

Debora: I did very much, there is a sensitivity in your portrayal—in the soft descriptions, in the story-by-story treatment of all the characters, in the isolating condition of small-town life. I find it to be a bit poetic, certainly soulful. Tell me though, what do you think about the end result? How would you describe what you have captured and how you got there?

Jim: I like the way it worked out. I think connecting the stories made for a much more unified book. Originally the chapters were independent stories, and at the suggestion of my editor at Islandport (Genevieve Morgan) I rewrote them with recurring characters and situations, and put them all into the same town. Oh, and made a river run through it (grin). I’m not sure the isolation of individuals is a small town attribute, though; maybe because there are fewer people involved it seems that way in a novel. Maybe you can single out characters more easily. But I think people everywhere are always struggling for connections, don’t you?

Debora: Yes, I do. I also think there is something to what you say about how the reader can single out characters more easily. The structure of your book is interesting, Jim, not only in the way you give entire chapters to the principal characters, but also in that these characters vary in age and make their first appearances in another character’s chapter—and in some sort of plot relationship to that character—and then as you mention, each makes recurring appearances thereafter. I like the circling effect this has on moving us through time and plot. All of this had me very involved with each individual and also their importance—their impact—as a member of the town. The other thing happening with point of view is that it shifts between third and first person. How did you determine whose story should be told in third verses first person? How did this serve the novel as a whole?

Jim: Well, for the most part I left the stories written in third person alone, because I thought a sort of unifying narrative voice would help turn these heretofore independent chunks into a novel-in-stories. If I remember right, I changed a couple into third for that reason. But there were certain chapters/stories that simply insisted on being told in the character’s actual voice. Early Blake’s chapter – one of three I wrote to plug gaps during the book’s conversion – appeared in a sort of Morgan Freeman voice that just carried it along, I couldn’t think of taking that away. Another was Arnold’s grownup chapter, and I was just really interested in hearing him speak, after telling his first story in third person. I wanted to listen to what he had to say.

Debora: This is your third book of fiction. And you have also authored many short stories. Do you know the total count? Among these works are numerous accolades, as well. Will you take a moment to provide us with some of the details of your successes?

Jim: Not a huge amount, actually, maybe 35 or 40 stories. I write all the time, but I’m not the most efficient at actually finishing things. But I have published in a couple dozen magazines, and have been lucky enough to receive several prizes, including the Willamette Award in Fiction and the Curt Johnson Prose Award for Fiction. I’ve been a finalist at magazines like Narrative and Glimmer Train and Prime Number. Also, my previous novel (Hull Creek) was runner-up for fiction at the 2012 Maine Book Awards, and won a silver medal IPPY award for regional fiction. Thanks for letting me grandstand a bit!

Debora: Well it’s well deserved, but I forced you, so it doesn’t count as grandstanding. Plus I was leading up to this question. As you look across all of these books and stories, has your writing changed? Are there any steadfast consistencies that typify your work?

Jim: I think and hope I’ve gotten better and more patient with it. As far as consistencies, I’ve always wanted to have a strong narrative voice that comes out of the characters’ own idiom. I have nothing against more sumptuous prose, as long as it relates to the characters’ own hearts and minds, but my own characters tend to be plain-spoken and direct. That doesn’t mean they can’t come out with an elegant turn of phrase from time to time, or that the narrator can’t.

Debora: Yes, those elegant turns account for the poetic feel that I mentioned. Do you have any specific intentions as a writer?

Jim: I’ve had people – including fellow writers – tell me that my work opened up new worlds to them, introduced them to people they hadn’t really thought about before. I think maybe my niche is to tell stories from this community: working class, small-town, sort of rural, independent, generally quiet. They don’t get that much literary attention, but I think there’s plenty of triumph and tragedy – sometimes quiet, sometimes not so much – to find within their lives. I think plenty goes on that maybe isn’t headline material, but that matters just as much as anything else.

Debora: Jim, since you are a Bill and Dave’s Cocktail Hour fan, you are aware that many of our readers are writers yet aspiring to craft their first complete pieces and also writers who are a little further along and landing their first publications. We would love to hear about what writing has meant to you over your years at the keyboard.

Jim: Well, it’s everything to me. I believe fiction is where truth really lives, and sometimes, if you work hard enough and are lucky, you might find a piece of it for yourself. You might stumble into something universal and manage to capture it well enough that someone else, reading it, will possibly nod their head and smile with recognition.

Debora: I’ve been away from your novel for days, and I’ve still got Tomi Lambert on my mind. You portray her so beautifully—in that soft-handed, sensitive way. As a girl of, what was she, 12? 14? She was such a bright light—free and smart, modest, kind, and on the go. And then the adult version, divorced, waiting tables, being rather objectified by all the males in town—everyone wishing they had a piece of her. She doesn’t seem aware of her light. I was surprised and a little disappointed to find Tomi in Baxter at all.

Jim: Don’t give up on her, Debora…Tomi’s got moxie and she’s still young. She’s a product of her upbringing, of course, and her time, and her small town, and she wasn’t looking very far ahead when she ran off and got married. But I think she grew, realized she deserved better and got out of that situation. Now she’s getting by, raising her girls, marking time maybe, but she’s still Tomi, I hope you can tell by the weary-but-witty remarks. She’ll be fine, it’s just going to take a little while because she has responsibilities and she’s not one to shirk them.

Debora: Actually, I do agree, Tomi is stellar in this moment and consistent with her character. I think it was the way she was involved with those photographs. Something penetrated. So I was surprised. However one thing that strikes me here, goes back to the notion of the way your structure so distinctly brings forward each character. Although we get to see Johnny—the most main character—evolve more completely than the others, we don’t get to see the other characters in quite that same start to finish. I’m not saying we should, it’s as you say—lives have stages and moments, and as we enter and exit these stories, the characters are at various places. But I have a lingering curiosity about them. I mean, look at Arnold! What a state he’s in! Do you feel any similar lingering sense of attachment to these stories? Have you considered writing a second book that continues with the same characters? Or is this a horrible idea?

Jim: I think that’s a great idea. I’d like to find out what happens to Arnold and Tomi, too

Debora: Let’s go back. You’ve just finished writing the book. I’m imagining that you feel a heaping sense of that Ta-dah! I did it! I love it! But your editor makes the suggestion that you go back in, that you take your short stories and thread the characters and events together. What did you feel in that moment? What was your gut reaction and what did you do from there? Which version do you like better—because I can see how the original set-up would work too.

Jim: Well, first off, I didn’t actually write it as a book. These were stories that I’d written individually and sent out to magazines, and after I’d had several published I thought I’d round them up and submit them as a collection. That’s how I’d done it with my first book, Slow Monkeys. But yeah, at that point I thought I was done, so to be asked to rewrite it as a novel gave me pause. It meant taking up the yoke again when I was ready to go back to the first draft of another novel I was working on. But the more I thought about it, the better I liked the idea. Genevieve’s notion of a more unified book sort of took hold, and I started to see associations and threads, how a person in this story could be an earlier version of a character in another story, that sort of thing. I got intrigued with making it work. It was a challenge. So I dove in, and five months later, resubmitted it. I like it lots better this way, so I’m glad it happened.

Debora: Jim what happens in a different set of circumstances when you think over and tryout an editor’s idea, but you end-up not liking it? How do writers and editors deal with that?

Jim: The only other time that’s really happened is when I was asked to swap the first chapter of Hull Creek with a later, more dramatic chapter (about a smuggling trip). I didn’t like the idea because it meant I had to start out with something I’d built up to before, and then change the 2nd, 3rd and 4th chapters into flashbacks, and then when I got to the 5th chapter transition back to present-time with no more flashbacks. I think in that case the book might have been better as it was originally laid out, there was a carefully-designed arc that was disrupted for a while, but the idea of a more dynamic beginning also had its merits, and I wasn’t sure enough that I was right to fight about it. It seemed to work pretty well as it turned out, at least as far as I heard.

Debora: What values and moral code do you live by?

Jim: You should probably have phrased that try to live by (grin). But that said, Do unto others… is as good a place to start as any. Empathy!

Debora: You were raised in a small, blue-collar town. What was your family like when you were growing-up?

Jim: My father was a WWII fighter pilot. My mother – an Army Nurse – married him after her first husband, also a pilot, was shot down and killed over the Istrian Peninsula (a la Tomi’s mother). So you can see I come from fearless stock. I was one of nine children, a rambunctious gang living out in the country. Five boys and four girls and we were our own best friends. We spent most of our time outdoors, but we were also all bookworms and had to be told to turn our lights out most every night. When my mother took us to church (she was French-Irish and Catholic) we occupied a whole pew. My father didn’t go because he was agnostic, and we kids inherited some of his skepticism and didn’t take the services all that seriously. Sometimes we’d sing just slightly off-key during the hymns to try and make each other laugh.

Debora: Sounds wonderful, Jim. You portray a similar sense of well-being within the town of Baxter. Describe what Baxter shows us. Because while I felt this well-being, I also felt—say in the cases of Larry and Sarah, a sense of constriction and disconnection—and in the scenes where the fishermen are competing for their catch and the cabbies are competing for clients—a sense of grating and limitation, like everybody is getting in the way of one another.

Jim: I think you’re right that there’s crowding and impingement because of the small scale of life in Baxter. It’s like one neighborhood, where people always know your business…take Johnny not wanting to walk home from a bar partly because someone might stop and offer him a ride, and then they’d know he’d fallen off the wagon. So right, there’s not the protecting anonymity you can find in a bigger place. But there’s plenty of warmth in Baxter, too. You have families laughing at Martian tales, a father and son racing toward home. And rosy-cheeked kids waiting for school buses, and lonely little boys meeting beautiful girls from Russia! There are centenarians joking about fishing, an adolescent’s first bewildering but thrilling kiss. And isn’t it joy that Johnny feels at the very end, riding with Early and James and Eric?

Debora: It’s a crystalline moment. You have said this is a novel about longing. And, indeed, your characters experience longing in different forms—wistful dreaminess, to longings that harbor secrets, to longings that reside on the peripheries of a darker nature, as might be in the case of Arnold. What drew you to the topic and what would you like readers to come away with from reading Closer All the Time?

Jim: Just that there are all these huge yearning lives going on everywhere around us.

Debora: I don’t think we can discuss longing without noting the scenes where we get to witness the characters in expression of their personal longings. Lead us through a thought or two from your writer point of view.

Jim: I think that expression of longing exists in every chapter, it does seem to be thematic (now that you mention it). For example you’ve got Johnny trying so desperately to think of a way to connect with his fellow-Martian son Eric, and poor Arnold going to eat repeatedly at the restaurant where Tomi works, just because she’s nice to him. You’ve got the aridity of poor Lawrence (of Arabia)’s heart, and the awkward way he and his stepbrother manage to irrigate it. And I think of Johnny and Early, their taciturn love for one another and how they honor that emotion without ever getting sentimental. Because getting sentimental just wouldn’t do, right? I wonder if all stories, when you get right down to it, have mainly to do with that human longing.

Debora: Let’s talk about your publisher, Islandport Press for a moment. They are out of Yarmouth Maine and have established an all-new February Fiction program—which honors you as the author of its first book release. It’s quite wonderful, the program and Closer All the Time being selected. I’m sure you would like to tell us more.

Jim: I love what Islandport is doing both with contemporary fiction – it is an honor to start the February Fiction series – and with their other categories of books. They have a great crew and leader. Bringing Genevieve Morgan on board as Fiction Editor was finestkind (as we say in Maine). Their focus on New England suits me to a T, of course and their moto – We tell stories – is perfect: plain-spoken but adamant. Islandport also happens to make beautiful books that I’ve bought in the past just on the promise that the covers presented.

Debora: Great team, great book, great cover. Many thanks to you and Genevieve for your literary insights and contributions and for spending time with all of us who meet online at Bill and Dave’s.

Jim: Thanks to you, Debora, for the kind words, the great questions and the close reading. And to Bill & Dave for providing such a wonderful forum for writers and readers.

Debora Black is a writer and athlete living in Steamboat Springs, CO. Check out her website here.

March 4, 2015

Bad Advice Wednesday: Why Not Say What Happened?

Robert Lowell

One of the most-asked questions at writer’s conferences and here on the Bill and Dave’s Bad Advice hotline is about the dangers of hurting or offending or simply alerting people who will appear in a memoir or even, disguised, in fiction. Here’s a particularly cogent version of the question, which we’ll keep anonymous by request: “I’m planning a memoir of my growing up partly in Nigeria, partly in London, mostly in the Chicago area. I’m terribly worried about offending my mother, who is sensitive about some of the material in the book (my father ended up in prison, and rightly so). Also, I’m worried about my children reading this material, as they are not fully aware of their grandfather’s story, nor mine (I have a checkered past, to say it mildly). How do you handle sensitive material when it will be out and about for all the world to read?”

First of all, this sounds like a great story. And my initial response is sympathetic. But then I want to ask, Why are you worrying about this now? You need to write the book first before you can know what to worry about. Write it unbridled. If the story is haunting you, get it on paper. Get it right both factually and emotionally, both technically and dramatically. This will take a couple of years. Later, you can always make adjustments to protect the innocent or not-so-innocent.

Better yet, like most memoirists, you may find that having found the truth means no adjustments are necessary. Like many, you may find that publication is elusive in any case. Like some, however, the big day is going to come. Most publishers give a legal reading to such manuscripts, try to determine if anyone’s privacy is being violated, or if any libel is being committed, and etc., and request changes, often artful obfuscations.

Before that, most editors will ask if you’ve made any disguises, changed names, fudged locations (above, for example, I said Nigeria and Chicago instead of your real country of origin and city of residence, since you asked to be anonymous). And a good editor will help you avoid trouble with some tried-and-true methods of disguise, up to and including composite characters. Then again, as the star of a memoir, you can’t very well change your name and identifying characteristics. And changing Mother’s name to Mommy won’t help much either. One enterprising friend attributed all her very most controversial behavior (she’d been a sex worker) to her sister, Ann. But she didn’t have a sister. My sense is it kind of worked–anyway, the memoir went forward, its point not being the sex trade but the effects of sexual abuse in her family.

Another possible strategy is to eschew publication till your mother is gone and your kids grown up, or maybe never. We don’t always write for publication.

Then again, we always do. So while you’re looking out for the feelings of others, remember that it’s your story, too, a story you have every right to tell.

Sometimes I’ve heard other writers suggest that you try your manuscript on all the people you’ve adopted as characters. But that seems a sure way to water things down, especially if controversy is involved. (If there’s no controversy, where’s the story?) Even with this strategy, I’d vote for writing the book first. And maybe act as a reporter rather than as a writer with a manuscript to vet. That is, interview your people, get their side of the story, and make sure you include their side in your book, if only to smash it. The interview will also have the effect of letting your people know what you’re up to. If there are going to be lawsuits, maybe better to get them sorted out in advance.

But really, most people are pleased to find themselves written about, especially if what they read sounds right, especially if what they read is well made. I’ve found that people love the stuff I was most afraid to say about them, and take offense at the most minor, surprising things: “Love how you handled my indecent-exposure trial, but I’d never wear a pink shirt to court!” And sometimes, as with your mother, a good book on a shared life can open up new channels of communication.

As for your kids, maybe it’s like the movies. There’s G, PG, PG-13, NC-17, and X. Eventually, they’ll reach the appropriate age for whatever your story holds. If you’ve been checkered enough, you might even find you’ve impressed them. Moreso, you might find they already know a great deal you never knew they knew. Because the things you do leave a trace. Just something about you, something that especially your own kids can detect. And isn’t it better to be who you are for those you love? I mean when they’re ready for it? So they know (as our “culture” likes to forget), that very good people can come out of very bad experiences?

Here’s a poem by Robert Lowell that speaks to the issue, and gives this week’s Bad Advice its title:

Epilogue

Those blessèd structures, plot and rhyme–

why are they no help to me now

I want to make

something imagined, not recalled?

I hear the noise of my own voice:

The painter’s vision is not a lens,

it trembles to caress the light.

But sometimes everything I write

with the threadbare art of my eye

seems a snapshot,

lurid, rapid, garish, grouped,

heightened from life,

yet paralyzed by fact.

All’s misalliance.

Yet why not say what happened?

Pray for the grace of accuracy

Vermeer gave to the sun’s illumination

stealing like the tide across a map

to his girl solid with yearning.

We are poor passing facts,

warned by that to give

each figure in the photograph

his living name.

March 2, 2015

The House at the End of the World

Take a good look at this photo—snapped last December by the marine biologist John Dindo on the west end of Dauphin Island, Alabama—and you can see almost everything that’s wrong about building homes along the coastline in this climate-changed, hurricane-prone, post-Sandy world. You can even make a game of it, if you want—sort of like one of those spot-the-error puzzles that you find on the children’s placemat menus at Red Robin. It’s easy to play along: Just print out the image and draw a big red circle around all the things that make no sense whatsoever.

Take a good look at this photo—snapped last December by the marine biologist John Dindo on the west end of Dauphin Island, Alabama—and you can see almost everything that’s wrong about building homes along the coastline in this climate-changed, hurricane-prone, post-Sandy world. You can even make a game of it, if you want—sort of like one of those spot-the-error puzzles that you find on the children’s placemat menus at Red Robin. It’s easy to play along: Just print out the image and draw a big red circle around all the things that make no sense whatsoever.

Here’s what I circled:

It’s obvious that this oversized house was built on an untenable spot. It’s practically asking to be flooded by the next major storm or taken out by the next hurricane. But what I’m really interested in is the owner’s second mistake—the one that ended up compounding the first one. In an attempt to protect his highly vulnerable castle, he has constructed his own private seawall around it. This seawall—which encircles, or rather ensquares, the house like a frontier fortification (and appears to be made out of Lincoln Logs)—is doing a good job, so far. The problem is that the job it’s doing isn’t one of protection: One look at the wall reveals that it wouldn’t stand a chance of holding back even a half-assed storm, let alone a full-on hurricane. No, what it’s doing instead is destroying the neighboring public beach.

To read more please go HERE.

February 28, 2015

Table for Two: An Interview with Melissa Falcon Field

Melissa Falcon Field and Noah

Debora: I’m so pleased to be among the first to announce your debut novel, What Burns Away. Kudos! How does it feel to know that bookstores all over the country are unboxing your book and making room for you on the Newly Released shelf?

Melissa: Well Debora, I have to say that it is wildly exciting. Publishing a novel has been a dream I have been chasing since my college days, back when I had a big spiral perm and wore stonewashed Daisy Duke cutoffs. Always, in those years, I carried an enormous bag full of books with me everywhere I went, furiously reading Stephen Crane, Annie Proulx, Jane Smiley, John Cheever, Eudora Welty, Raymond Carver, Willa Cather, Andre Dubus, Stuart Dybeck, Mary Karr, Annie Dillard, and so many more. I read literally everything I could get my hands on, studying plotlines, and working hard to develop my own with a ferocious appetite, I still read to inform my craft. But the debut, holding my own work in my hands, it feels like a big deal—a graduation of sorts, a kind of birth, and a sense of legitimacy after chasing the dream and working as hard as I have to understand how to write a novel, for some twenty years now. And, mostly, I am full of gratitude for all the great mentors and literary friendships that gave me doses of the necessary tough love along the way.

Debora: I thoroughly enjoyed reading this book. It was an intense read, thrilling. Claire makes for such an interesting character—she is well educated, she is a successful career woman—I really identified with her and got caught-up in all the things coming at her. I kept setting down the book to think over her circumstances.

Melissa: I’m so glad you enjoyed it, that alone is very important to me, and I am further happy to hear that the protagonist in What Burns Away, Claire, gave you pause. What I loved most about writing Claire is that she initially seems to have it all, until it is revealed later that despite her education and her career successes, she is haunted by a past that has left her unhinged in ways that are both universal and surprising. It’s the past disintegration of Claire’s childhood family woven with the current time narrative of her own crumbling marriage and the reappearance of an old flame on social media, seeking to drag her back into his orbit, that unhinges Claire in that moment of new motherhood and marital hardship. The catalyst for her change of course is that past creeping up on her, reeling her back through time. What I knew when sketching Claire was that I had to access all that residual danger still inside of her, the risk-taking she tucked away after becoming a wife and mother, and that is precisely where the case study of the fire made its way into the narrative. I worked hard to rationalize how trouble manifests itself in the life of a woman who has a solid grasp on chemistry, physics and weather patterns, utilizing those kinds of deliberations that would be made by a successful climatologist, to help inform Claire’s motivations. I lured her into the fire, using the hauntings of old flames, both literal and figurative, throughout the novel. And, I’ll even admit to you, that I played with fire myself, as part of my research to write this book, setting my flames in the back yard, and once, accidentally burning our chicken coop to the ground. No causalities, thank goodness. Just a bunch of stunned hens watching on, perplexed.

Melissa: I’m so glad you enjoyed it, that alone is very important to me, and I am further happy to hear that the protagonist in What Burns Away, Claire, gave you pause. What I loved most about writing Claire is that she initially seems to have it all, until it is revealed later that despite her education and her career successes, she is haunted by a past that has left her unhinged in ways that are both universal and surprising. It’s the past disintegration of Claire’s childhood family woven with the current time narrative of her own crumbling marriage and the reappearance of an old flame on social media, seeking to drag her back into his orbit, that unhinges Claire in that moment of new motherhood and marital hardship. The catalyst for her change of course is that past creeping up on her, reeling her back through time. What I knew when sketching Claire was that I had to access all that residual danger still inside of her, the risk-taking she tucked away after becoming a wife and mother, and that is precisely where the case study of the fire made its way into the narrative. I worked hard to rationalize how trouble manifests itself in the life of a woman who has a solid grasp on chemistry, physics and weather patterns, utilizing those kinds of deliberations that would be made by a successful climatologist, to help inform Claire’s motivations. I lured her into the fire, using the hauntings of old flames, both literal and figurative, throughout the novel. And, I’ll even admit to you, that I played with fire myself, as part of my research to write this book, setting my flames in the back yard, and once, accidentally burning our chicken coop to the ground. No causalities, thank goodness. Just a bunch of stunned hens watching on, perplexed.

Debora: Have you always known that you were a writer? Have you written any short works or has the novel always been your pursuit? How did your MFA program fit-in to your goals? Exactly how did everything evolve for you?

Melissa: I have been writing ever since my undergraduate studies at the University of Maine at Farmington and throughout graduate school, where I earned my MFA at Texas State University. Since high school, tearing through novels, I always knew I wanted to be a writer, but my journey took a tegmental route. After my graduate work in Texas, I joined Teach For America to become an inner city schoolteacher and work toward national school reforms, but always, during those years, I wrote in the stolen hours between teaching and night school, where I worked on a second Master’s Degree in Education. Yet, it wasn’t until I went back to teaching college-level classes, after nearly ten years in urban education, that I was able to have enough continuity in my writing life to work on long form narrative, a novel, successfully. In between I published a few short stories, reviews, articles and a lot of curriculum, but the book took flight when I had the luxury of carving out four full days a week to dedicate to reading and writing the novel exclusively. It took about a year and a half to get a first draft. Then, I put it away for just over a year, after the birth of my son and during my husband’s and my decision to move to the Midwest. Shortly there after, once all our boxes were unpacked and my little boy began to toddle, I pulled out the manuscript and read every book I could that was written in a similar vein. One writer in particular, Jillian Medoff, was a huge influence at that time. And while I revised, I read anything tagged ‘domestic suspense’ by booksellers, and looked in the acknowledgements to find agents noted by the authors I loved. I made lists of those agents and agencies, twenty in total, and sent out fifteen simultaneous, unsolicited query letters to literary agencies in New York and Boston. It took about six months for me to hear back from anyone, but then slowly requests for full manuscripts, and also some rejections, came in. I ended up sending out ten full manuscripts of the novel. I got six requests for phone calls. In the end, I had a handful of offers for representation, but chose my beloved agent, Jennifer Gates at Zachary Schuster Harmsworth, because not only did she have the most enthusiasm for What Burns Away, but also she offered prescriptive ideas for revision before we sent it out. Jen’s wisdom not only helped me make a more beautiful novel, but also led me to a publisher, Sourcebooks, who shared her same enthusiasm for What Burns Away. Shana Dhres, my editor there, connected to Claire’s story right away and the book found its home with her, at the largest woman-owned trade book publisher in the United States. It was all very exciting and I can’t begin to explain how grateful I am to these women, Jennifer and Shana, who helped make it all happen.

Debora: While you were writing What Burns Away, your life—perhaps similar to Claire’s—was very busy and complicated, or at least complex. Describe what was going on and how that impacted your work. What specifically did you do to keep the writing going—or was it easy to keep that part moving forward?

Melissa: My protagonist, Claire, as you suggest, is in some ways both like and unlike me. At the time I was working through a second draft of What Burns Away, I was a new mother myself, lost to a cross-country move with an ambitious husband, who had his head buried in work. And in that period of time, I will admit, I was no longer certain who I was, or who my husband and I were together. But the writing was my anchor—and I felt, as I always do, that I had to engage it some, touch it, or read it. Some days I wrote just a handful of sentences to move it forward, other days I blasted through pages until I got a solid draft, then, with the help of librarian Katherine Clark at the Sequoya Branch of the Madison Public Library, in Wisconsin where I had moved from Maine, I retrieved and read all of Michael Faradays’ Lectures from his lecture series at the Royal Academy of London, The Chemical History of a Candle. The research helped me flush out scenes that were slim. It added layers to Claire’s story, and also gave her an authority that she lacked in earlier drafts. During the revising and research, I further separated Claire’s story from my own, by learning more about fire, Claire’s draw to it, and came to understand that danger brewing inside of her, which allowed the story to grow fully aflame.

Debora: In the Acknowledgements at the end of the book you are giving thanks to friends and colleagues. You arrive at Michael Field, your husband. You say the most intriguing thing, that Michael had told you that one-day you would thank him for all that is unconventional in your lives. Wow! He had us at unconventional! Details, girlfriend. Start with the context of him saying this.

Melissa: Oh man—well I am married to a quirky and dear man. Not a writer, quite the opposite—a doctor and musician, both. And, in the early years of our courtship, we made promises to each other about encouraging our dreams, mine in writing, his in medicinal research and technology, and so when we moved to Madison, Wisconsin for his work, my husband encouraged me to take all that I was feeling, my homesickness and loneliness, and channel it into a book. So that is exactly what I did. Michael has always pushed me to use our private obstacles as strengths in the work, challenging me to explore myself and our troubles, encouraging me to take risks and adventures that other husbands might not be so open to, nudging me to find my way in the world and write my way through points of crisis—ours and those we collectively observe. It is an unconventional practice and one for which I am most grateful.

Debora: What would you say if I said that Miles got off easy?

Melissa: I would say I worked really, really hard to leave readers’ feelings about Claire and Miles open to interpretation, hoping that sentiments might be divided among the audience. I always find it a compliment when book groups tell me they have had a lively, or better, a heated conversation about what is coming down the pike for Miles and Claire, questioning both their trouble and their atonement.

Debora: I love that you give us a fairly uncomplicated plot, but you manage to turn up the heat so that the reader feels the tension in each moment. And it builds steadily. Even the ending is tense, now that I think about it.

Melissa: Thank you for that, Debora. I was really focusing on tension in this work. The way relationships can come quietly undone then heat up, as the trouble bubbles over.

Debora: There are several themes running through What Burns Away. One that I find particularly striking has to do with the way in which Claire interprets the world as if her desires are less consequential than the men around her. Would you say this is true? Or is it something else? What are your thoughts?

Melissa: Well, I think the best way to answer that is to say that what I see in Claire is one woman’s search for balance and normalcy—hers rendered through desire. And I am especially interested in that moment in which a woman realizes her youth is more behind her than it is in front of her, giving her pause. For some women, or at least for Claire, marriage and motherhood force her to take a long look at the second half of her life, and to decide what kind of life it is that she wants to live. She thinks a lot about what she can no longer live without, what needs to be tossed aside, and how she wants to be loved. It is this middle age “awakening,” particularly in women that I was interested in as subject matter. There is something about remaking yourself as a mother, in terms of desire and sexuality that really fascinates me. What was once sexy, what once felt like desire, is driven by different external factors. It’s both freeing and horrifying, and in Claire’s case, destructive. But sometimes you must burn down the barn to see the moon. And in Claire’s case this burning is not about female versus male consequences, as much as it is about a middle age woman’s changing concept of beauty, finding what is left underneath her youthful pretty, learning to love the lines notching time in her face, understanding the value and wisdom brought by living a full, and perhaps more dangerous life. I loved writing a character in this space, acknowledging these things about her and allowing Claire to behave in reaction to the process of reinvention and rekindled desires, which is both brutal and transformative, and why I felt compelled to capture her quest, inside the novel.

Debora: It’s that extra complication in deciding to redefine normalcy and herself that makes Claire the kind of female character we like to read. And Miles, too, has his own set of realizations. Looking ahead, what will be your next step?

Melissa: I’m currently working outside the bounds of normalcy altogether on a second novel about a series of accidents that intimately connects four strangers—two women, a teenaged boy and a sexy and extremely unstable helicopter pilot. It is a third person narrative that works as a study of grief caused by the omens of dead birds, who rain from the sky and curse the landscape of the Calendar Islands, located off the coast of Maine. I have about 225 pages. It’s a mystery of sorts, and I’ve already gotten some great feed back so I am very excited to finish the first draft.

Debora: Sounds like another winner, Melissa. I know what you mean about finishing a first draft. You can feel it, that you are there. Melissa you have been touring, as you mentioned in our correspondence, like a lunatic, so I can’t thank you enough for spending time with us at Bill and Dave’s Cocktail Hour. It has been wonderful to hear your writer view on What Burns Away and all of the life content that brought you through from conception to publication.

Melissa: Thank you Debora for making such a close study of the book and for looking at the themes that ultimately illuminate the complexity of marriage under duress. What I hope is that What Burns Away provides both an anatomy of a marriage and its toxic effluence, revealing the hidden truths in every relationship and breeding that kind of tainted love that recasts the way we define ourselves in our public and private worlds, our past and our present lives, as they collide into one another. Thank you again. It was my pleasure to sit at this table for two!

Debora Black is a writer and athlete living in Steamboat Springs, Colorado. Find her on the web at www.deborablack.com