Stephen R. Graves's Blog, page 9

October 27, 2020

3 Types of Transitions

ESPN does many things well. They’re the best in the business when it comes to delivering daily highlights, news, and expert analysis. They’ve got the best college sports coverage, and with the launch of the 30 for 30 series, they’re even leading the way in documentary film. They’re also pretty good at making commercials, many of which feature self-deprecating cameos from star athletes who trade in their cleats and sneakers for a desk (or a copier).

Unfortunately for us, life and work transitions can often feel much like this commercial. Whether it’s leaving a career and launching out on our own or simply taking on new responsibility in our current role, one thing seems to hold true: transitions rarely go exactly as we planned. The challenges tend to be more difficult, the hurdles higher, and our weaknesses more acute. Many a newly-minted small business owner has sat alone in his office and echoed the words of Will Ferrell’s Ron Burgundy, “I immediately regret this decision.”

So, how can you succeed? How can you smooth the transition and soften the landing?

It starts with identifying what kind of transition you’re dealing with. In my experience, nearly every transition falls into one of three categories: a road extension, a lane change, or a highway transfer.

Road Extension

For the past fifteen years, Northwest Arkansas (my home) has invested millions of dollars in the Razorback Greenway—a biking/running trail that snakes for thirty-six miles through four cities. Over the years, I’ve probably sweated out my body weight biking on that trail.

I imagine they could have done the whole thing in a year or so, but instead, they’ve simply added to the trail, a little at a time, extending the road a bit further ahead each month and year. In fact, for years I’ve driven past groups of workers in one town or another pushing the path forward. Same path mind you … just an extension.

This is exactly what happens when you take a promotion doing the same kind of work you’re already doing, only with a little more responsibility and a little wider scope. It’s what happens when you inherit a new wrinkle or nuance of your business. At the end of the day, despite the change, it’s really just more of the same.

A “road extension” is usually the lowest impact transition because nothing has changed in the core competency of your business. You’re still the same person, doing the same work, in the same place … just doing things a little differently. Don’t be fooled, though. These transitions still test your foresight and preparation.

3 Questions to Ask:

Am I extending the road because I have nothing better to do or because it’s really worth it?Can I stay engaged and committed to this type of task for another run?What roadblocks and detours might lie ahead?

Lane Change

A “lane change” is what every successful television star does when they go from the small screen to the big screen. Some make it (Will Smith). Some don’t (the cast of Friends).

It’s staying on the same highway system, but changing lanes for one reason or another. It’s the marketing executive who changes companies but stays in marketing. It’s the EVP who becomes the CEO of a company she is very familiar with and has years of experience in. It’s an assistant coach jumping to a head-coaching job at a new school. It’s a business integrating horizontally, like PepsiCo moving into the sports drink business with Gatorade (it’s the same highway of drinks).

A lane change necessarily has more variables than a road extension. There’s an entirely new set of relationships you have to develop, new skills to master, and old ones to sharpen. Even if you’re using the same business muscles, you’re using them in an entirely new way.

3 Questions to Ask:

How clear is the new assignment in regard to expectations, roles, and rewards?How will my experience and capabilities transfer to this new lane? What is the same and what is different?What can I do to increase the probability of a smooth transition?

Highway Transfer

This is the most radical of the three kinds of transitions. A “highway transfer” is a person in one career jumping to a completely different sector or kind of business. In other words, you exit your current highway system to travel on an entirely new one. This could be a new structure, new market, new setting, or new role.

In my coaching business, I’ve helped dozens of leaders navigate this type of transition. I’ve helped business owners leave to take a subordinate role in another industry. I’ve worked with corporate executives making the jump to launch their own business. I’ve seen health care professionals jump out of the surgery center and try their hand at building the next technological breakthrough. I’ve even counseled academics walking away from tenured positions to chase their chance at business innovation.

These men and women have to learn skills they never knew or have long forgotten. They have to pick tax structures and design processes from scratch. They have to learn the cultural, relational, and even political nuances of their new station. They may even have to transition from a steady stream of income to a bootstrap mentality and uncertain revenue. It’s a totally different ride!

3 Questions to Ask:

Who should I go to for wisdom? Who has driven this highway before?How much gas do I have? In other words, how are all my resources looking (time, money, energy, knowledge, etc.)?How does this highway change line up strategically with my calling?

No matter what kind of transition you’re beginning or about to approach, the key is to pause and ask some key questions before you make the change. Pause too long and you may miss the opportunity, but if you don’t pause at all, you risk calamity.

The post 3 Types of Transitions appeared first on Dr. Stephen R. Graves.

October 20, 2020

3 Principles for Managing a Crisis

Is it just me or does the idea of “crisis” dominate contemporary media? Seemingly every time you turn on the TV, pick up the newspaper, or check your phone updates, you’re greeted by an announcement of the latest harbinger of death or impending collapse of social order. The Financial Crisis. A World Health Crisis. The Border Crisis. Natural Disasters. The Political Crisis … just to name a few. Everywhere you look, one thing seems clear—you’d better start stocking up on canned goods and bottled water, because the end is near!

Maybe that’s true. Maybe things really are that bad. Maybe we are just one good hiccup away from the collapse of civilized society.

Or, perhaps the more likely explanation is that as humans, we’re prone to hyperbole and the 24-hour, instant information age we live in feeds and exacerbates that tendency.

While this latter explanation certainly seems to be at least partly to blame, I think there is also another significant issue driving the media’s attention to crisis, and that is the poor management of crises. There’s no way around it—in recent years, months, and even days, prominent leaders, both in the public and private sectors, have done a lousy job handling crises. It seems that every day, new headlines are created by a leader not handling something well.

My interest, though, is not to rehash mistakes that have already been sufficiently dissected elsewhere, but rather to attempt to use those mistakes as a wake-up call for all leaders. In the same way that a crisis can be a catalyst for change, let’s allow the crisis of poor crisis management to spur us to more carefully consider how we approach significant changes and problems in our lives and organizations.

While you probably won’t be spearheading a global response to a contagious disease anytime soon, if you lead any organization for long enough, you will have to navigate some difficult waters:

A merger or acquisition that leads to large-scale layoffsA disruptive shift in the marketplace that challenges the heart of “how” you do businessGrowth that combats your cultureAn ethical failing of a leader within your organization or another employee disappointmentThe unexpected death of a senior leader or founder

When those times come, how you as a leader approach the situation may ultimately decide how, and even if, your organization makes it to the other side. With that in mind, here are some critical principles of crisis management that I’ve both learned and observed over the years.

Make sure someone is leading – People want to be led, and they want to be led well. This is never truer than in a time of crisis. When uncertainty and fear abound, someone must act as a steadying presence. The worst thing leaders can do in a time of crisis is recede into the background and leave everyone to speculate. When a crisis hits, make sure everyone knows who is in charge. This person doesn’t have to have all the answers or put out every fire, but you have to manage the emotional stage and help steer people forward.Control the flow of information – At first glance this may seem like an ethically questionable area, but keep in mind that I’m absolutely NOT telling you to mislead those you are leading. What I am saying is this: during a crisis everyone needs to know something but everyone doesn’t need to know everything. Too much information can overwhelm and confuse. Too little can lead to rumor and speculation. Identify the vital information and share it transparently and appropriately.Share in the pain – In a time of crisis, organizational leaders must never lose sight of the human component of their decisions. One of the easiest ways to lose the faith of those both inside and outside of your organization is to insulate yourself from the consequences of change. If salaries and bonuses are being cut, if hours are being increased, you as a leader should feel the pressure as well. In fact, as a leader you must be willing to feel it more acutely and bear a greater portion of the burden. Set an example in the difficult things, and those you are leading will follow.

As I said earlier, if you lead in any capacity for long enough, you will have to navigate some type of crisis. You likely won’t have much say in what your crisis is or when it comes, but how you respond is entirely up to you.

The post 3 Principles for Managing a Crisis appeared first on Dr. Stephen R. Graves.

October 13, 2020

The Know-It-All Who Knows Nothing

You think you know it all, don’t you?

You probably wouldn’t say it that way (and neither would I), but we all generally trust our own perceptions. Even as you approach an article like this one, you measure what I say against what you believe, your experiences, and the things you value. That’s not always wrong, but it’s definitely not always right. And too often, it’s a form of cognitive bias—we all have some faulty hardwiring in our brains.

But you already knew that, right?

The Bible talks a lot about the idea of overly trusting yourself. One of my favorite books in the Bible, Proverbs, is all about wisdom and folly; toward the end, it drops this bombshell, “Do you see a man wise in his own eyes? There is more hope for a fool than for him” (Proverbs 26:12).

In short: Overly trusting yourself is dangerous. Naturally, a dosage of self-confidence is crucial to living a healthy life—but not overconfidence.

The Bible discusses two different ways in which people become blinded by their overconfidence in themselves.

Hypocrisy

Hypokrites, the Greek word for hypocrite, appears in the New Testament and actually originates from the ancient Greek stage. Hypokrites refers to an actor who wears a mask on stage, literally, “an interpreter from underneath.” In other words, a hypocrite is two-faced, presenting one face outwardly while the true actor hides beneath.

In the Sermon on the Mount, one of the things Jesus zeros in on is hypocrisy. He warns, “Watch out for those who give money in order to gain attention from others. Or those who pray or fast for the same reason.”

These hypocrites pretend for public acclaim. It may fool people for a time, but it never fools God, who can always see behind the mask.

What about you? Where in your life are you acting? We all have gaps between who we are and who we aspire to be, but there are surely areas where we choose to wear a mask. Those decisions are dangerous.

Self-Deception

In his 1850 novel The Scarlet Letter, Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote, “No man for any considerable period can wear one face to himself, and another to the multitude, without finally getting bewildered as to which may be the true.”

In the New Testament’s Book of James, the author describes a person who looks in the mirror and genuinely does not see the person in front of them; they see someone who is patient, self-controlled, and reasonable. The problem is that they alone see themselves as that person; everyone else sees through the veil.

Self-deception is much harder to outgrow because you are convinced of a lie.

Conclusion: Is there help for the hypocrite and self-deceived?

We all have blind spots. If you could see them, they wouldn’t be blind spots. Some of these blind spots are dangerous, while others are not. You have things—habits, biases, patterns of thinking and acting—that you can feel good about and that may be very healthy.

The good news is that you can train yourself to turn your head toward your blind spot. Harvard Business Review suggests some ways to do this in their short 2013 article, “Three Tips for Overcoming Your Blind Spots”, but I’ll add my own.

I know myself to some degree, and I’ve worked with leaders for three decades, so I’ve seen some overly strong self-belief over the years. The following are some ways I’ve learned to deal with it.

Give a few trusted people permission to speak on your life: perhaps a spouse, a boss, a friend, a pastor. What disconnect do they see between who you are and who you say you are? Understand that you might have to specifically solicit their opinion and not just give them the freedom to share whenever they want to. Most people just don’t like playing that role.Listen to and read from perspectives you wouldn’t normally encounter. Train yourself to listen first and critique later. My friend, Max Anderson, offers a great newsletter that includes five articles on a single topic each week (check it out.) He always ends his newsletter with the phrase, “Read widely. Read wisely.” Love that phrase.Carve out some time for regular reflection and ask yourself the hard questions. Where have you faked it over the past week/month/year? Where have you been overly defensive? In what areas might you have blind spots? How long has it been since you last received hard feedback?

It takes work to doubt yourself and to remove the mask, but it’s worth it. Don’t just consider yourself to be wise. Be wise.

The post The Know-It-All Who Knows Nothing appeared first on Dr. Stephen R. Graves.

October 6, 2020

Good Leaders Have a Limp

Maybe you’re familiar with the story I’m referring to. It’s found in Genesis 32 in the Old Testament. Alone for the night, the patriarch Jacob is confronted by “a Mysterious Man,” and the two wrestle for hours. Toward the end of the night, the God-man touches Jacob’s hip, and Jacob is defeated. The God-man blesses Jacob, leaves him, and from that day on, Jacob has a limp.

Up until this point, Jacob has always found a way to come out on top. But now he has come up against an opponent he cannot beat. Jacob is broken—and he is better because of it.

What is a limp?

In three decades of coaching executives, I’ve spent time with a lot of people who, like Jacob, keep coming out on top. But constantly winning can position our confidence and certainty on the wrong person.

However, I have noticed another trait among the most remarkable leaders I have met. They carry a limp.

What’s a limp? A limp is a scar that comes from getting in the ring with God. A limp is the spiritual, emotional, mental, and even physical (at times) recognition that we are not the supreme agent of life. The faster I can learn that I don’t know all, can’t do all, and am not completely the person I need to be… the better. Have you gone through a moment or a season where you realized, as Jacob did, that you do not have the amount of control that you thought you did?

A friend of mine says that the issue for every person is, “Who has the right to rule?” Jacob was wrestling with God over who was in charge. He had spent years ruling his own life, and it seemed to be working. He did what most people won’t admit is true about themselves—he acted as if he didn’t need God.

Wrestling with God

Perhaps you, too, spent years winning at everything in life and then, all of a sudden, it was gone.

Maybe, as I did a couple years ago, you suffered an illness that threw your mortality in your face. Or the corporate strategy you spent months designing flopped. The corner office you spent years angling for was given to someone else. You didn’t make the team after working harder than anyone else. Your marriage or your kids didn’t turn out the way you planned. In other words, something broke the “up and to the right” momentum.

As for Jacob, he was having conflict with his brother, but as Ligon Duncan, a Mississippi pastor said, “The real battle was between God and Jacob. Esau was a sideshow. Esau was an occasion. Esau was a circumstance.” (You can read Duncan’s whole sermon on the passage here.)

When the issue is who has the right to rule, it’s always a wrestling match going up against the Almighty. A limp comes when you battle God, and God decides to win.

Why do we need a limp?

Two things are trickle-down realties of a limp: Humanity and Humility. These two things are inextricably tied, and bad things happen when we lose a grip on either one.

We all can picture people who have lost touch with their humanity, people who act as if they are superhuman. Athletes, movie stars, preachers, business owners, and CEOs come to mind. Well, actually it is more of a mindset rather than a vocational address … and it could happen to any one of us. It can happen to anybody whose life experience has taught them that the rules don’t apply to them. It can happen to people with high authority and low vulnerability, as my friend Andy Crouch says in Playing God: Redeeming the Gift of Power.

The second by-product of a limp is humility. You can always spot it in people who have wrestled with God and lost.

This wrestling is a good thing because until we wrestle with God, we don’t have to face our humanity. There is no substitute for wrestling with God. Like a wild horse that must be broken before it destroys itself, we must go through the experience of being broken.

“Brokenness” sounds bad, as if something is wrong with us. But what if brokenness is a good thing? The Bible, after all, continually talks about brokenness and weakness being the places where God shines through.

As John Calvin wrote, “Only those who have learned well to be earnestly dissatisfied with themselves … truly understand the Christian Gospel.”

Brokenness for Jacob brought about a new name (Israel) and a reminder for the rest of his life of God’s power over his own—a limp.

The greatest leaders I know have a limp. They have found their humanity and they walk in humility. It might be defeat, disappointment, or any number of things that reframes who has the right to rule.

The post Good Leaders Have a Limp appeared first on Dr. Stephen R. Graves.

September 30, 2020

Slaying the Giant: A Tricky Lesson on Ambition

A few years back, Nike ran a marketing campaign entitled, “What’s Your Motivation?” In this ad, the protagonist is a teenager working to improve his game at 3:00 a.m.

He’s driven by the motivation to prove doubters wrong, to make the team, maybe even to make the NBA someday.

Clearly, he’s got ambition.

Ambition is a tricky word, especially for people of faith. I was reminded this the other day when talking with a young CEO. I commented that we all have layers of ambition; in other words, a few different things can fuel our motivation. I then told him a story.

David and Goliath

Our story begins with Israel—a centralized nation of only a few years—and its new king, who is already being tested. Israel is at war with the neighboring nation of Philistia. Led by Goliath, its literal giant of a leader, Philistia is pummeling young Israel.

Each day, the giant comes out on the hillside to taunt the Israelites and their God. No one seems able to defeat the giant.

David is on an errand for his family when he summits the hill and beholds the giant. Naturally, he is challenged, confused, taken aback.

He asks the soldiers in the neighboring camp, “What will be awarded to the man who defeats the giant?”

The soldiers sneer and say, “King Saul offers his daughter’s hand in marriage, a bag of money, and tax exemption for life.”

This response turns the wheels in David’s head and heart.

It is with layers of motivation (in my opinion) that David forms a plan to face the giant. As he prepares, he secretly asks once more about the prize, just to make sure he is clear. And then he is off.

David boldly proclaims that God will give Goliath into his hands to show that his God is the true God. (Note that he doesn’t shout, “I am here to claim my tax exemption and to get the girl!”)

So, what motivates David to defeat the giant? Is it personal gain, or honoring God? I’d say it is some of both, but it’s clear that he has his priorities in proper order. He has a primary and a secondary motivation: an eternal motivation and an earthly/temporary one.

David’s ambition is to raise the name of the God of Israel, but he also carries with him a personal ambition and is excited by the prospect of receiving the king’s reward.

I would argue that David’s ambition is a good thing; it motivates him to face an overwhelmingly difficult situation. The prospect of the reward simply lights the fuse.

Malcolm Gladwell wrote about this scene in his book David and Goliath: Underdogs, Misfits, and the Art of Battling Giants, and coins these as “desirable difficulties.” As Gladwell said in an interview, “Do we have an accurate understanding of what an advantage is?”

Disadvantages spark our ambition; ambition moves us to action.

The Danger Isn’t Having Ambition

In his book, You Are What You Love: The Spiritual Power of Habit, James K. A. Smith argues that we all have ambition. We all run and work toward what we love.

We sometimes forget this and act as if lack of ambition is the goal. Perhaps this is a millennial and Gen X reaction to watching their parents slave for years for the corner office and a bigger paycheck.

“We won’t be like that,” they say, and chase more meaningful work and more friends with whom to work.

But we are all chasing something.

One group is abusing ambition, sure, but the other group is ignoring it. It’s still there, though, because ambition is part of who we are. We all want for something more. Whether the reward is internal or external, we have ambition to claim that reward.

Ambition isn’t a bad thing. It just needs to be kept in its place.

The Danger is Unharnessed Ambition

Elvis said, “Ambition is a dream with a V8 engine.” I’d put it this way: Ambition makes for great gasoline but a horrible map. In other words, it can motivate you to move forward, but if you let ambition determine your aims, you’ll end up way off track.

I wrote about this a little while back in a blog called “The Two Hearts of Ambition,” which argues that ambition is amoral; it can be positive or negative.

Take David, for example. He has ambition and a desire for a reward that motivates him to fight for his people and for the honor of God’s name. His ambition rescues an oppressed nation.

However, years later, as king, David’s ambition leads him to have an affair, manipulate a man’s death, and number his people—all in direct disobedience to God. In each of these cases, David’s ambition exalts himself.

David’s ambition and desire for the king’s reward is partially what gets him to fight for his people and for the honor of God’s name, but as king, his ambition leads him to overstep—to disobey God.

When Paul writes, “Do nothing from selfish ambition” (Phil 2:3), the emphasis is on self-seeking. Be ambitious but aim for something that benefits something beyond yourself.

Ambition must be harnessed to purpose.

Conclusion

David Brooks critiques the “GPA mentality” that, he says, encourages students to answer others’ questions instead of asking their own questions. Instead, he argues, we must allow and empower students to run down new lanes dictated by their own ambition. People are driven by the autonomy of determining their own fate and solving their own problems (see Drive: The Surprising Truth about What Motivates Us, by Daniel H. Pink, for research and thoughts on this topic.)

In the corporate world, this could mean:

offering rewards to those who identify and solve problems, but not telling them how to do it;setting goals for growth;holding yourself to a vision statement that includes bringing about change in your community and in the world.

Don’t hide or be embarrassed by your ambition. Instead, use it and push others toward it. Interesting things happen when ambition and a reward system meet face-to-face.

The post Slaying the Giant: A Tricky Lesson on Ambition appeared first on Dr. Stephen R. Graves.

September 22, 2020

Three Dangers Every Founder Faces

I’ve worked with hundreds of founders in my three-plus decades of executive advising. Men and women representing all shapes and sizes of organizations. Massive nonprofits and hometown businesses, Fortune 100 companies and boot strapping start ups.

I believe founders face some atypical challenges.

I love founders. I love the risk they take and the courage they have. I’m one myself (sometimes a successful one and sometimes a failed one), and I know how hard it is to start something that lasts.

Starting a business or enterprise is difficult. Sustaining it through hard times and scaling it in good times requires an even more diverse skill set. Try to find one person who can do all three of those things well—start, sustain, and scale—and you’ll be looking for a long time.

Most founders are able to start the organization but then, the very skills that helped them start the organization often become the problem. This is often referred to as the Founder’s Syndrome.

This Forbes article does a good job of clarifying the concept.

Over and over again, I’ve seen founders struggle with the same three challenges: overreaching your narrative, one-dimensionality, and insularity.

Overreaching Your Narrative

At the beginning, the brand of the organization is inextricably linked to the founder (and understandably so). Microsoft was Bill Gates, Blake Mycoskie was TOMS (and vice versa) in the early days. If the founder doesn’t press his/her personal narrative there would be no organization.

As the organization grows, however, there should be healthy separation. The organization must develop a narrative other than simply that of the founder. It must birth a culture, mission, and vision with edges other than the founder’s passions, gifts, and personality. Otherwise the organization will delay in growth and development.

For example, if the founder is driven by hyper-ambition, the organization is in constant growth mode. If the founder loves victory, the organization is out to defeat all competitors. If the nonprofit founder expresses only compassion, the organization may quickly exhaust its resources.

The founder has a narrative, but so does the organization. And over time they must find a healthy separation.

One-Dimensionality

Put simply, most founders are workaholics with all the energy focused on the organization we birthed. Very often we say, “it doesn’t feel like work” because we enjoy the work so much. It is very common for founders to have no hobbies and no life away from our work.

Every growing organization asks more and more from the founder. In the end you can feel trapped. You’ve invested so much of yourself into the organization that dialing down could topple the very thing that defines you.

But every founder must grow as a leader and as a person at the same time they are growing the organization. And this will only happen if the founder has a fierce conviction of the value and payback from making that investment.

I call this “building a composite scorecard.” This includes the many roles in life other than the founder/work role. This includes nurturing my inner person, my physical health, my relationships, my faith, my service to my community, my family, etc.

Over time a founder with no life other than working in the organization he or she birthed will find himself in trouble. Succession becomes impossible. Fulfillment eludes us. Recruiting and retaining balanced leaders can’t happen. Having a healthy company culture unravels. And then the crash of all crashes happens if for some reason the organization doesn’t make it (which happens more times than not).

Insularity

Without outside perspective, the founder can drive the car straight off the cliff.

I always say, “You don’t know what you don’t know.” Therefore, I need people around me who can help, not simply regurgitate my own point of view.

The film Lincoln was based on Doris Kearns Godwin’s book Team of Rivals. Godwin wrote that Lincoln’s genius lay in his decision to surround himself with people who disagreed with him.

Most founders, though, build a circle of folks who only give good news. They often establish their board like this: The founder calls his accountant friend and says, “I’m starting an organization and I need somebody who can do the books. Want to be on the board?”

That organization will wake up five years down the road with a rubber-stamp board. Why? Because those board members are essentially volunteer staff. All power and influence resides with the founder. Decisions (including staff hires) are rarely debated or tested.

In this scenario, the founder says, “Jump!” and the board says, “How high?” All strategic direction comes from the founder and the organization ends up lurching headlong from one ditch into another. The board is working for the founder rather than the other way around.

Wise founders find dissenting viewpoints and learn when to listen to them.

Conclusion

To some degree, I can’t blame founders. Noam Wasseman (author of The Founder’s Dilemmas) says that only 16% of businesses have single founders, and Harvard Business Review says that only 25% of businesses ever return the projected return on investment.

Therefore, the few founders who have launched a successful organization have, to some degree, earned the right to self-confidence. They’ve emerged successful in the “survival of the fittest” world, so listening to others seems like folly.

This argument is the kind that looks to heroes like Henry Ford, Walt Disney, and Steve Jobs, singular figures who created cultural icons.

And yet, Henry Ford had to shut down his assembly lines in 1927. Disney stock rose the day Walt Disney died. Steve Jobs was fired by his own company. In each of these cases, the founder let his personal narrative, one dimensionality and insularity stifle the growth of the company.

Founders are a gift to the world. Without them, much would just be hype and hot air. But that amazing contribution doesn’t automatically erase the challenges with the role. If you are a founder, think deeply on the three big dangers mentioned above. Spotting them early is so much easier than the damage and confusion caused late in the game.

The post Three Dangers Every Founder Faces appeared first on Dr. Stephen R. Graves.

September 15, 2020

The Five Stoplights of Business Deals

I’ve been coaching executives for about 30 years, and I’ve never had such a concentration around the area of mergers and acquisitions. Start-ups and established companies, for-profits and non-profits, family-owned companies and Fortune 1000 companies. Across all industries, it seems like everyone is considering buying, selling and/or merging.

Just because everyone is doing it doesn’t mean it’s easy, though.

This Harvard Business Review article is a bit dated (2011), but it says that between 70% and 90% of mergers and acquisitions fail. I’m willing to bet that the number hasn’t changed much in the past decade.

Despite this reality, much of my portfolio the last five years has been exploring their options.

For some it’s a stage of life thing. They’re tired and ready to take their foot off the gas, so they would like to sell. For others, it’s as simple as needing a new challenge. For some, the business demands it. Methodical organic growth doesn’t allow the company to go where the owners/leaders desire. For others still, the possibility of an exit/cash out is just too enticing. Someone whispered the potential value of a sell and the $$$$ can’t be shaken.

The problem is that no matter the reason for looking at a merger or acquisition, the final decision is often made with the gut. It’s not a good idea to hire from your gut, and merging, selling or acquiring from your gut is no better.

Simon Sinek said, “Mergers are like marriages. They are the bringing together of two individuals. If you wouldn’t marry someone for the ‘operational efficiencies’ they offer in the running of a household, then why would you combine two companies with unique cultures and identities for that reason?”

Instead, work the process and objectify the decision. I recommend to look for a “fit” in five areas: economic, culture, timing, role and vision. Without a green light at each step you might be headed into a disaster at worst or at least a huge disappointment.

Economic Fit: This is the obvious one. In most mergers and acquisitions, the conversations start and stop around finances. Someone’s got to provide a fair valuation and then the other party needs to agree. What’s this thing actually worth? Keep in mind, though, that in any good deal, both people can’t win on everything. One side might win on price (how much?) and the other side might win on terms (how soon or what is included?). Be careful to resist greed and make sure you are being fair and reasonable. Anlways look for any hidden economic factors. On yea, one last thing, more times than not the economic fit requires a little dancing so be patient, stay fair and work the process.

Culture Fit: In my book, The Five Tasks: What Every Senior Leader Must Do, I say that one of the “musts” for senior leaders is to set culture. In other words, “we will work and operate in this manner” here in this company. Any consideration of a merger, sale, or acquisition must likewise include good alignment on culture. If you’re selling, you want to sell to a company that treats employees and people the way you would. If you’re merging, you need to look at the working styles of the senior leaders and make sure those line up. Does the other founder treat risk and compensation the same way you do? Is one leader more generous or stingy in treatment of people? Does one owner pull as much money out as possible every year while you push growth capital back in and wait for your payout? If you swapped out your company’s values for the company’s you are merging with, what would change?

Timing Fit: Why now? Even if you can afford to buy or merge (or even sell), and it makes sense, should you do it…now? Do you have the internal organizational bandwidth to keep this ‘great opportunity’ from turning into a train wreck? Even though it’s a deal, is it still too rich for you at this time? If you pressed pause for 6-12 months, what would change? Does having more data make a better decision or is the opportunity lost? What is the worst-case scenario if I pass on this opportunity? What are the other elements surrounding this buy/sell/merge that impact timing? I remember when my kids were young I would often say when pressed to make an on the spot decision, “The answer is no if you must have an answer this second. If you can give me a few hours, and we can chat about it tonight, then perhaps the answer is yes.” Translated – don’t get suckered into “this deal is going away if you don’t do it this second.”

Role Fit: Buyer’s remorse happens in business too, and in many cases it’s tied to misalignment on roles post-acquisition. Fight for clarity on whether you’re supposed to be the banker, just providing the money, or whether you’re going to be an operator doing the five tasks of the senior leader. In other words, is this a passive investment or an active (operational) investment? Where is the role redundancy? What happens if one leader is hard charging and the other is easy going and relaxed? What if one is a top-line growth leader and the other is bottom-line cost conscious? Is one leader fast with decision making while the other is slow and methodical? Role clarity and fit among the senior leadership is crucial.

Vision Fit: The HBR article I referenced earlier says there are two main reasons to pursue an acquisition. The first is to boost performance. The second is to “reinvent your business model and thereby fundamentally redirect your company.” Is this merger or acquisition about the first or the second reason? If the first, you better make sure that you’re aligned on vision so vision fracture doesn’t kill performance. If the second, you better make sure that you’re aligned on vision because you’re about to go somewhere new. It is usually helpful to know the intentioned endgame. Buy and hold? Milk it down? Build it and flip it? Where are things going?

Conclusion

A local investor friend of mine says that in long-term buy/sell arrangements, you start by making a long list of things that are important to you. In most cases, you can group those items into these five categories: economics, culture, timing, role, and vision. At that point, mark each of them with green, yellow, or red lights. Then, look at your colors, and in most cases, the “go,” “advance with caution,” or “stop” becomes pretty clear.

The post The Five Stoplights of Business Deals appeared first on Dr. Stephen R. Graves.

September 8, 2020

4 Metrics of Child Rearing

A recent conversation with a friend about business recruiting actually highlighted a couple of parenting insights.

I was meeting with a CEO who was evaluating his internship program. In determining whom to hire out of this program, he looks for only three capabilities:

Work ethic

Problem solving ability

Relational skills

GPA is not on the list. A list of athletic awards is not on the list. Generations of family success are not on the list. A certain personality is not on the list.

The more I thought about it, the more universal I thought those three capabilities really were. As I often do, I discussed this theory with my family and with some other empty nesters. The more we looked at these factors as measures of success for parents, the more we liked them.

Let’s look at each in turn and possibly give you an insight or two on recruiting or parenting.

Work Ethic

Mike Rowe, the host of Dirty Jobs, cautions, “We’re churning out a generation of poorly educated people with no skill, no ambition, no guidance, and no realistic expectations of what it means to go to work.”

It’s tempting to read that quote and throw more ridicule at Millennials. But notice in his quote where the fault lies—with those who are “churning out” these individuals.

As parents, we must instill work ethic in our kids. If work is a four-letter word in your house, your kids pick up on that. If you do all the work around the house while they play video games, they likely will have low initiative. If you carry all the weight, they will forever be weak. Give them jobs and projects that will take time and effort. And then don’t intervene when it gets heavy, messy, or inconvenient.

Beware: If your children don’t learn the value, honor, and utility of hard work while they are under your tutelage, they will be handicapped for life.

Problem Solving Ability

Have you seen any remarkable problem solving lately? In the movie, The Martian, Matt Damon plays a NASA botanist stranded on the Red Planet after an unexpected sandstorm forces his crewmates to abort. Damon is mistakenly left behind and his only chance for survival is to “cultivate” Mars. Although he doesn’t have much of the ordinary astronaut training, he has one incredible muscle—problem solving—and he took that into space with him.

In other words, you want kids and employees who can think outside of the box in order to solve a problem. Problem solving channels initiative, risk, and creativity. Problem solving makes us sort and prioritize, and then eventually make choices. Although problem solving comes more natural to some people, it is a trait anyone can cultivate.

Every life and every job is full of problems. Some problems are massive roadblocks. Others are small struggles. Some touch money and some touch relationships. Some have both.

One executive I know says problem solving is the thing that has been lost more than any other trait in the last generation. I will leave it to others to tell us why, but I might agree with the assessment.

Relational Skills

When I advise clients on hiring, I always tell them to look at character, competence, and chemistry. In my experience, it’s chemistry that is most often overlooked. We forget how big of a benefit it is to hire people who, quite simply, are enjoyable to be around and “play well with others.” Instead, we wrongly focus on their hard skill abilities.

I am afraid we parents often make the same mistake. Often we concentrate on our children’s athletic abilities and their intellectual achievements while neglecting their relational skills. We forget to teach them how to do things like have good conversations, be an active listener, develop empathy, and be a good friend.

This Harvard Business Review article points out that good relationships must supersede any business relationship. Relationship means caring for a person and not just what they can get you or give you.

Spiritual Vitality

I added this one to my friend’s list. I think any view of a successful life must include the spiritual component, and I’ve always tried to implant that value into my children. I don’t want them to have their dad’s faith, but I also don’t want them to ignore my faith.

The book of Proverbs is one of my favorite books of the Bible, and it’s mainly advice from a parent to a son or daughter. The book pretty much starts out with these lines: “The fear of the Lord is the beginning of knowledge. … Hear, my son, your father’s instruction, and do not forsake your mother’s teaching.”

Imparting spiritual vitality is core to God’s evaluation of our parenting.

Conclusion

These four metrics are the broadest, most universal assignments of childrearing. Get these four done and you’ll never be disappointed with your kids. Sure, you may have some frustrations and pain, but on a macro level, you’ll be satisfied, perhaps thrilled, and hopefully grateful.

Be aware, you need all four. If you have only three, there are major consequences—like a car with a brand new battery, a solid starter, top-of-the-line brakes but no gas. Therefore, you have to pay attention to the neglected element.

What about you? Which of the four do you need to buckle down on with your son or daughter?

Work ethic? How can you give her more responsibility in 2020 or 2021?

Problem solving ability? What are his three biggest problems and how can you take a step back and let him learn to solve those problems himself?

Relational skills? If he’s too cautious relationally, encourage him to come prepared for conversations. If he’s overconfident, challenge him to take on the role of the active listener.

Spiritual vitality? Pick a book of the Bible and read it together, with a weekly discussion over breakfast.

The post 4 Metrics of Child Rearing appeared first on Dr. Stephen R. Graves.

September 1, 2020

4 COVID Impacts

There’s a meme going around that says, “Whoever said ‘The days go slow and the years go fast didn’t know 2020.’”

What a year.

I’ve worked my way through a few mask styles, read some books I didn’t know I’d get to, let a prepaid annual parking spot at our airport sit empty, watched a film series or three, and bigger than all of these, pulled off a wedding for my oldest daughter. After only 3 or 4 COVID pivots.

What a year.

On the work front, every client I have (and more than a few friends) has wanted to talk through the impact of COVID on their organizations. It’s become the great leveling of the playing field in some respects; we’re all going through it.

One friend called the other day and asked if I would come talk with his leadership team about some of the impacts I’ve seen from COVID. I’m hesitant to do talks like this because I’m just one guy with one seat to watch this from, but I’d seen enough from clients at this point that I was starting to see a few trends, so I agreed.

We met outside, doing the whole socially distanced thing and talked for a couple hours. I came up with four personal and organizational impacts from COVID, and after I finished, I thought I’d share them with you here.

Again, I’m not trying to be exhaustive here (I’m on the board of Praxis, and our CEO wrote an excellent and extensive analysis of the season called Leading Beyond the Blizzard: Why Every Organization is Now a Startup), but these four insights are what I’m seeing from friends and clients across the country and across the industry landscape. Hope they help you make sense of this disorienting season.

1.) COVID is a pressure test for every organization.

The old saying is “What comes out of a lemon when it is squeezed? Whatever is in the lemon.”

I guarantee it: COVID has shown you some things about your organization. It renders a score, exposing some weak areas that need shoring up, and highlighting some things that are more deeply rooted than you thought.

Over the years, one of the tools that I’ve used to do a quick assessment of a company’s viability and health is The 4 Wheels of Effective Strategy. Customer, People, Offering, and Financials. If one of these four wheels is flat or out of balance, you’re in for trouble. Maybe not right away, but it’s coming. During COVID, all 4 of these things have been pressure tested.

I know a company who has learned that their entire culture depended on being in close proximity. I have watched companies designed for gathering scramble to survive. People who firmly believed remote working would never work for them are big believers now.

Running within, through, and around all four of these categories are questions of values and culture. As you look back at the past six months, do the things you called values show up crystal clear? If not, they probably weren’t that clear to start with. How has the pressure test of COVID been for you and your company? Learn anything?

2.) COVID doesn’t treat all organizations equally.

While COVID has had impact on every company and organization, the exact impact has differed, falling into one of four categories: disaster, hyper-growth, pivot, bridge. Which are you?

Disaster: This is you if the combination of pandemic and your pre-existing risk meant the end of your organization. Big-name companies like Hertz and Lord & Taylor have declared bankruptcy, but I’ve also seen it in my hometown as restaurants and small businesses have shut down. It’s happened to companies dependent on March Madness tourism and churches without an online platform for giving. It could have been poor planning, but it also could have just been bad timing. You didn’t have the balance sheet or the cash to carry you through; you saw the writing on the wall and you shut it down.Hyper-growth: There’s definitely some of you who are “all systems go.” It’s a good time to be in the hand sanitizer business. Wal-Mart’s online sales surged 74% through April 30. And Zoom has become a verb. Anybody tried buying a boat, bike, tent or pickle ball set lately? Yes, some of you are just figuring out how to keep up with all the growth you’ve run into.Pivot: The Praxis article I mentioned earlier highlights this possibility, saying “Set aside your current playbook” and lean into “the creative potential.” The pandemic is a once in a lifetime opportunity to reset things that aren’t working or to try out new things. Most health care providers sped up their telehealth offerings, restaurants are offering curbside pick-up and delivery, churches are shifting care back into the hands of church members, universities are moving courses online, even the NBA is getting in on the act, trying out new technology and playoff structure.Bridge: There are some industries in which business will look pretty much the same as normal once we get to the other side of COVID. The manufacturing company may have lower numbers during COVID, but the equipment still runs the same way and will on the other side once demand increases. The non-profit answering educational needs in developing countries will restart as school restarts. College football, the airline industry, these things are too big to not survive even without wholesale changes. They have to innovate a bit of course, but mostly, they just need to make it to the other side.

Which one are you? Once you know which group you fall into, it guides your decisions. Do you need to get out fast (disaster)? Double down (hyper growth)? Listen to the right voices (pivot)? Cut costs (bridge)?

3.) COVID makes us slow down and refocus

I know that there are some people (health care workers, for example) who have not slowed down, but the vast majority of us have. I can’t tell you the number of people who have told me, “I’ve spent more time with my wife and family in the last few months than I have in years.” Hedges have never been so trimmed, the book stack on the nightstand is going down, the basement is cleaned, sons and daughters are learning to fish and throw a baseball. You might even be eating healthier.

We are people of routines and habits and like Newton’s first law, something in motion stays in motion until a greater force stops it. Habits…meet COVID.

The question is, “What have you done with the chance to reset?” Were you one of the 15.8 million new Netflix subscribers (not all bad)? Or did you reinvest in your relationships and in self-management? I sometimes talk about my “oikos,” that is, my relational orbit. During COVID, the orbit has gotten tighter. Have you invested more in those in your orbit?

As for self-management, what has COVID shown you about what you depend on for joy and satisfaction? What habits have you started that you don’t want to lose when this is over? COVID has given you a chance to slow down, take stock, and make adjustments. Take advantage of it.

4.) COVID exaggerated differences and brought us together at the same time.

Ever had an ambulance screaming down the street, getting closer and closer, and then it stops at the house across the street? 2020 feels that way a bit, like an alarm screaming for attention that has just parked itself.

Except it’s not just one alarm in 2020, it’s at least three. Check out anything from Facebook to NPR over the recent months, and you’ll hear voices screaming about three topics in particular: health care, the economy and politics. (And as a sidenote: most people have one alarm that is most important. They’ll talk about that one more than the other two.)

When disaster strikes, people generally set aside their differences and rally together. We see this when there’s a natural disaster like a tornado, but we also saw it at the beginning of COVID. People weren’t faking it then, they were uniting around their common humanity. As John F. Kennedy famously said, “We all inhabit this planet. We all breathe the same air.” I’d say it’s that we’re united in our carrying of the divine image of God.

But when the crisis is over, or even begins to ebb a bit, we go back to ideological differences. This is particularly evident during an election year, when candidates proclaim their differences loudly. Candidates and normal people on social media alike try to hoard the microphone.

It’s good to have points of view about these things; I do. But it’s also good to remember that you’re not an expert in everything. When the weatherman says, “Hurricane coming! Get out of town!” he’s not thinking of economic impact or transportation infrastructure to get people out of town. We need his voice, but we don’t need only his voice.

In a season with conversations around health care, the economy, politics, and much more, as people tend to devolve into hardened camps, it’s worth not hardening yourself. Listen to wisdom and remember common humanity.

It’s been a long year, and it’s not over. We need wisdom and to remember our common humanity.

The post 4 COVID Impacts appeared first on Dr. Stephen R. Graves.

August 25, 2020

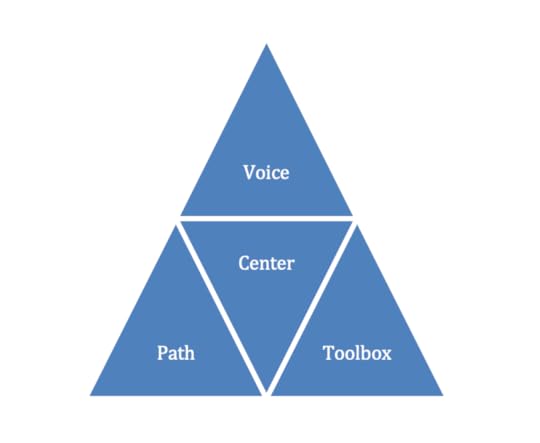

Voice, Center, Path, Toolbox

Frameworks are good. They help steer our imagination and energy. They help us focus on the things that matter most. They create repositories of insights that can be recycled at a later time.

It is common for me to find myself having a conversation with a bright-eyed millennial ready to change the world. And it is also common for me to have a conversation with a seasoned executive considering a 2.0 or 3.0 career. In other words, they are contemplating leaving their current platform and relocating to another.

More times than not I will think through a single framework to help. It is Voice, Center, Path, and Toolbox.

Voice—My Unique Sound

I have to discover and get comfortable with (but not get addicted to) my voice. In life, my voice is that unique sound of me operating in my created and discovered giftedness. It is my personal signature on life and work. It is me finding my unique wiring. Sure, others influence me but I don’t aspire to be other people. I aspire to be all that I was created to be.

When we operate out of our voice, others straighten up and pay attention. Like the audience who hears Susan Boyle in this masterful moment:

Your Creator has hardwired you uniquely; no one has your exact DNA, no one has your exact set of experiences and passions. And certainly no one has the blending of all these things the way it shows up in you. It is the unique “you,” but unless what is created is discovered, it will stay buried under weeds and rubble. Find your voice regardless of how young you are, how old you are, where you sit on the org chart, what your title is, or where you derive your income.

Center—The Footing of My Life

Maybe this season in our world has shaken you—personally, organizationally, emotionally, financially. When, as the old hymn says, “all around my soul gives way,” what do you fall back on?

Options abound:

FamilyAchievementsReligionMoneyEducationNatural TalentsHard WorkFriendshipsAdventureService

Where are your security, significance, and success anchored? Your center is your bedrock, the core foundation that your personal operating system is built upon. It is the thing we default to over and over again.

Without a firm center, my point of view will always be moving around, my morals will always be shifting, and my goals will jump from one target to the next like Solomon in the Book of Ecclesiastes. I will be destroyed by indecision on the one hand and foolish hastiness on the other.

But with a strong center, there is true peace, genuine deep confidence, and astounding contentment. When we understand our center, we don’t try to do everything and we don’t simply respond to crises. We have a settled-ness that guides and governs our life and work.

Path—Journey and Destination

Where is your life headed? Are you truly making progress or are you just spinning in place for weeks, months, or years at a time? Do you have a compelling vision for the future pulling you forward or are you sidelined from progress and contribution?

Identifying my unique voice and establishing my foundational center assists when I am choosing the targets and paths of life.

Life’s path is never as straight as we envision. Traffic, potholes, and car trouble always change our plans. At least it does in my journeys, and for many of us, the past year has felt more like a car crash altogether. We must have a doggedness to keep an eye firmly on the destination and the flexibility to adapt to changing circumstances.

Among the most strategic assignments of any leader is to determine where the organization is going and not going … at what speed … at what risk. That is a leader’s job. In the same manner we must determine those same items for us personally in our own journey.

What does this mean? It means you can’t get distracted by every shiny object. That will often send you down the wrong path. It means you can’t stand paralyzed, waiting for someone else to fix your world. It means you might have to step into an intersection and commit to a new direction that would require a new level of risk or energy.

Wanting to go somewhere and even knowing how to get there doesn’t automatically transport you there. You have to jump in and take the journey.

Toolbox—The Things We Carry

We need tools (resources) to accomplish our life and work. The better the instruments, the better our performance.

My toolbox contains the instruments that I acquire along my path that move my confidence and competence upward. These instruments might be a knowledge bucket, a skill, a relationship, a business model, a business sector, a style of work, a rhythm of work, a set of guidelines or truths, etc.

Another element in your toolbox is stage and setting. We perform and produce better in some settings than others. We are more comfortable and natural on some stages than others. Some people need a strong collection of support players around them. Others just need a computer and a coffee shop. Some people thrive in large corporate settings and others must have a fast-changing entrepreneurial culture. For some people, working from home during a pandemic has increased effectiveness. For others, productivity is way down. These are all part of your optimum toolbox.

Of course, no two toolboxes are exactly the same. Your toolbox has to fit your learning style, personality, temperament, and calling. Keep building it. The pandemic has probably revealed some tools you need. Beware of trying to get by with other tools, and don’t forget what you’re learning now. Figure out how to go get those tools.

Conclusion

I have been guiding executives for three decades. Those who have done the hard work of nailing down their Voice, Center, Path and Toolbox seem to thrive better than those who haven’t. During this challenging season, it’s becoming even more clear how these four things root us and drive us forward. Maybe it’s also becoming clear where your lack is in these categories. Don’t give up hope. I’ve told many an executive over the years the same thing—press in.

The post Voice, Center, Path, Toolbox appeared first on Dr. Stephen R. Graves.