Gretchen Rubin's Blog, page 27

May 11, 2021

What Are the Habits that We Most Want to Make or Break?

When I was working on Better Than Before, my book about how to master our habits, I spent a lot of time talking to people about the habits they wanted to make or break.

Habits matter, because habits are the invisible architecture of everyday life. If we have habits that work for us, we’re much more likely to be happy, healthy, productive, and creative. Or not. Whenever I talk to people about their happiness challenges, they often point to hurdles related to a habit they want to master.

For Better Than Before, I identified the "Essential Seven," the areas in which we most often seek to foster better habits. Over time, however, as I've reflected further, I think I'd recast those categories a bit, and expand them.

No catchy name yet (have any suggestions?), but here's the list of habit categories as I think about it now:

Energy: exercise and sleepRelationships: connect and deepenProductivity: work and progressCreativity: learn, practice, playRecharging: relax and restOrder: clear and organizeMindful consumption: eating, drinking, spending, scrollingMindful Investment: save, support, experiencePurpose: reflect, identify, engageDoes this list ring true to you? Are there any habits that you try to foster, or aims that you've set for yourself, that don't fall into one of these categories? Can you see a nuance that isn't quite captured?

May 6, 2021

Katy Milkman: “What Works Depends on What’s Obstructing Change.”

Interview: Katy Milkman.

Katy Milkman is a professor at the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School, host of Charles Schwab’s popular behavioral economics podcast Choiceology, and the former president of the international Society for Judgment and Decision Making.

She's also the co-founder and co-director of the Behavior Change for Good Initiative, a research center with the mission of advancing the science of lasting behavior change. She's written for publications such as The Washington Post, The New York Times, USA Today, and The Economist.

Her new book is How to Change: The Science of Getting From Where You are to Where You Want to Be (Amazon, Bookshop).

I couldn't wait to talk to Katy about happiness, habits, and human nature.

Gretchen: What’s a simple activity or habit that consistently makes you happier, healthier, more productive, or more creative?

Katy: My morning routine involves listening to my favorite podcast – The Daily – while I get ready for work. I love that I can combine waking up in the shower, brushing my teeth, putting on lotion, and picking out clothes with a deep dive into current events. I thrive on information, so this habit ensures I start each day feeling happy, informed, and refreshed even though I rarely have time to sit down and read through a full newspaper.

What’s something you know now about happiness that you didn’t know when you were 18 years old?

When I was 18, I had no idea how much of my own happiness would emanate from finding meaning and purpose in my work. I feel lucky that I stumbled into a career that provides me with such a strong sense of purpose because I didn’t know to go looking for one.

You’ve done fascinating research. What has surprised or intrigued you—or your readers—most?

Most people (myself included) tend to think that when you give advice to someone else, you’re doing them a selfless favor. But I’ve learned from working with a brilliant scientist named Lauren Eskreis-Winkler that when you give other people advice about how to achieve a goal in an area where you’d also like to improve, it helps you a lot.

Why? First, being asked for advice boosts your self-confidence. Second, it causes you to dredge up insights you might not have otherwise contemplated. Finally, once you’ve given someone else advice, it feels hypocritical not to take it yourself.

I was lucky enough to collaborate with Lauren on one experiment where we showed this. We invited high school students to spend a few minutes writing down tips for their younger peers about how to study more effectively. We found this activity improved the advisors’ own grades in the class they cared about most.

A lot of people find it surprising that when you play the role of advisor or mentor to someone else, it turns out to help you, the advice-giver. But the data is incontrovertible, and I think it’s a wonderful insight because it means helping other people is a win-win (and it feels great too!).

Have you ever managed to gain a challenging healthy habit—or to break an unhealthy habit? If so, how did you do it?

When I was a first-year PhD student in engineering, I consistently struggled to get myself to the gym at the end of a long day of classes even though I knew getting regular exercise would boost my energy in the long run. And that wasn’t because I always turned straight to my problem sets and assigned readings, either—I tended to procrastinate on my schoolwork too because I needed a release at the end of a long day.

Midway through that first year of graduate school, after complaining again and again that I just couldn’t motivate myself to go to the gym, I had an idea about how I could simultaneously start exercising and stop procrastinating on schoolwork. I did something I’ve come to call “temptation bundling:” I started letting myself indulge in my guilty pleasure—novels like Harry Potter and The Da Vinci Code—at the end of a long day, but only during trips to the gym. I’d get the books I wanted in audio form and listen while using the elliptical.

It worked like a charm. Suddenly, I started craving trips to the gym at the end of a long day to find out what would happen next in my latest novel, and I stopped procrastinating on schoolwork when I was home because I’d already enjoyed a guilty pleasure and a bit of release. Not only that, but I enjoyed my novel and my workout more combined—I didn’t feel guilty reading the novel, and time flew at the gym.

I’ve since done research showing that this “temptation bundling” technique can be useful to other people, too. It can help anyone who is trying to find ways to make something they ought to do more alluring (and waste less time on an indulgence in the bargain). [Gretchen: I call this the "Strategy of Pairing."]

Would you describe yourself as an Upholder, a Questioner, a Rebel, or an Obliger?

Apparently I’m an Obliger. It’s certainly true that everything worth doing, I’ve found I do best when working with other people on a team. Accountability to my collaborators keeps me motivated and fulfilled.

Does anything tend to interfere with your ability to keep your healthy habits or your happiness?

Oh yes. I’ve found that disruptions to my routines can be a real challenge. One of my former PhD students, Hengchen Dai (now a professor at UCLA’s Anderson School of Management), did seminal research on just how troublesome disruptions can be when you’ve got a rhythm going. She showed this in controlled laboratory experiments, but she also has a wonderful study where she shows it affects the performance of Major League Baseball players when they’re traded to a new team. We’re all pretty susceptible to this. It’s funny because disruptions can be fantastic when you’re in a rut. But when you’re on a roll, they’re often a disaster.

Have you ever been hit by a lightning bolt, where you made a major change very suddenly, as a consequence of reading a book, a conversation with a friend, a milestone birthday, a health scare, etc.?

Absolutely. I’ve had a lot of lightning bolt moments. In fact, the day I bought a new home was the day I decided I was ready for a big new adventure to go with it and decided to write my book! Observing this tendency in myself actually helped spur my research on the power of fresh starts. My collaborators and I have documented a “fresh start effect:” we proved that moments like birthdays, holidays, and even Mondays can cause us to step back and think bigger picture about our lives, which has a meaningful impact on our motivation to change. We feel more eager to take on new challenges and more disconnected from our past missteps at these kinds of fresh start moments because they give us the sense that we have a clean slate. And so we’re more likely to begin pursuing new goals, more open to setting money aside in a 401(k), and we’re even more likely to simply visit the gym. [Me again: I call this the Strategy of First Steps; also the Strategy of the Clean Slate.]

Is there a particular motto or saying that you’ve found very helpful?

I know this is hokey, but I love the saying “Shoot for the moon, and if you miss, you’ll still land among the stars.” I remember finding that quote etched into the paint in a bathroom stall at a Chinese restaurant my family visited regularly when I was a kid, and to my 10-year-old self, the words seemed really profound. Silly as it may sound, I’ve found it’s quite a useful mantra as an adult. When you aim high, things often don’t work out exactly as hoped, but you normally do end up somewhere pretty good (even if you don’t reach your most ambitious goal).

Has a book ever changed your life – if so, which one and why?

Absolutely. I read a book about behavioral economics by Richard Thaler called The Winner’s Curse (Amazon, Bookshop) when I was a first year PhD student studying computer science and business, and I was so absolutely fascinated by it that I decided to change course and become a behavioral economist. The book is all about curious ways that people deviate from making optimal choices, and it made me fall in love with the field Thaler had helped found.

In your field, is there a common misconception that you’d like to correct?

I’d say there’s a common misconception that behavioral scientists have come up with a handy bag of tricks that can be used efficiently to nudge people to make better decisions and that you can just pick a trick from that bag, set it to use in your life or organization, and change will follow. What drives me crazy about this is that yes, we’ve found a lot of really effective ways to change behavior for the better, but if you just pick a tactic haphazardly, you’ll likely be disappointed. What works depends on what’s obstructing change.

Let me give you a couple of examples. If people aren’t getting flu shots in your organization because they forget to show up at the on-site clinic on the one day when it’s open and no one reminds them, making the experience of getting a flu shot more enjoyable and efficient is unlikely to change behavior much. However, a well-timed reminder campaign could have a huge impact. But reminders can also fall flat if they’re matched with the wrong obstacle. If you run a hotel chain where some customers stubbornly refuse to re-use their towels (hurting the environment and your water bill) because they think re-use must be unhygienic, a reminder probably won’t help. But telling customers that the vast majority of guests re-use their towels at this very hotel may well change behavior substantially since it will disabuse holdouts of the notion that there’s something peculiar and unsanitary about re-using your hotel’s towels.

Hopefully these examples help illustrate the point I’m trying to make: we can get a lot farther, faster using science to help people change for the better if we first take stock of the obstacle we need to overcome and make sure the behavioral science solution we’re deploying is well-suited to tackle that obstacle.

May 4, 2021

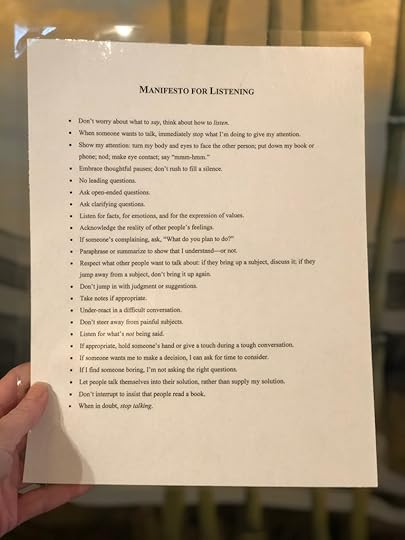

To Help Me Do A Better Job, I Made a “Manifesto of Listening.” What Did I Miss?

For my book about my five senses, I've been investigating my sense of hearing—and so I've thought a lot about noise, silence, and listening.

True attentive listening is powerful, and arduous. I'm not a great listener, so to help me do a better job, I wrote a Manifesto for Listening. I do love a manifesto! (For instance, you can read my Happiness Manifesto, Habits Manifesto, an Outer Order, Inner Calm Manifesto, and Podcast Manifesto.)

Of course, to listen, I have to fall quiet. Just a few days ago, I realized that word "silent" has the same letters as the word "listen," rearranged. Did everyone else know this?

Here's my Manifesto. I laminated it and stuck it up on my bulletin board to help me remember to listen better:

Don’t worry about what to say, think about how to listen.When someone wants to talk, immediately stop what I’m doing to give my attention.Show that I’m giving my attention: turn my body and eyes to face the other person; put down my book or phone; nod, make eye contact; say “mmm-hmm.”Embrace thoughtful pauses; don’t rush to fill a silence.No leading questions.Ask open-ended questions.Ask clarifying questions.Listen for facts, for emotions, and for the expression of values.Acknowledge the reality of other people’s feelings. (This is surprisingly difficult.)If someone’s complaining, ask, “What do you plan to do?”Don’t multi-task.Paraphrase or summarize to show that I understand—or not.Respect what other people want to talk about: if they bring up a subject, discuss it; if they jump away from a subject, don’t bring it up again (we all have our pet subjects that we love to discuss but others may not!)Don’t jump in with judgment or suggestions.Take notes if appropriate.Under-react in a difficult conversation.Don’t steer away from painful subjects. (I realized that I often do this, before I’m even consciously aware of what’s happening.)React with enthusiasm to good news. (Especially important with Jamie: research shows that partners’ response to good news is very important for the strength of a relationship)Listen for what’s not being said.If appropriate, hold someone’s hand or give a touch during a tough conversation.If someone wants me to make a decision, I can ask for time to consider.If I find someone boring, I’m not asking the right questions.Let people talk themselves into their solution, rather than supply my solution.Don’t interrupt to insist that people read a book. (This may be my particular problem. Whatever the challenge, I can’t resist pushing my favorite book on the subject. This is my way of showing love, but I should listen rather than interrupt to insist, “Here, write this down, you have to read this book.”)When in doubt, stop talking.What did I miss? Please let me know. I find that distilling my aims in this way really helps.

April 30, 2021

What I Read This Month: April 2021

For four years now, every Monday morning, I've posted a photo on my Facebook Page of the books I finished during the week, with the tag #GretchenRubinReads.

I get a big kick out of this weekly habit—it’s a way to shine a spotlight on all the terrific books that I’ve read.

As I write about in my book Better Than Before, for most of my life, my habit was to finish any book that I started. Finally, I realized that this approach meant that I spent time reading books that bored me, and I had less time for books that I truly enjoy. These days, I put down a book if I don’t feel like finishing it, so I have more time to do my favorite kinds of reading.

This habit means that if you see a book included in the #GretchenRubinReads photo, you know that I liked it well enough to read to the last page.

When I read books related to an area I’m researching for a writing project, I carefully read and take notes on the parts that interest me, and skim the parts that don’t. So I may list a book that I’ve partly read and partly skimmed. For me, that still “counts.”

If you’d like more ideas for habits to help you get more reading done, read this post or download my "Reading Better Than Before" worksheet.

You can also follow me on Goodreads where I track books I’ve read.

If you want to see what I read last month, the full list is here.

And join us for this year's new challenge: Read for 21 minutes every day in 2021!

A surprising number of people, I've found, want to read more. But for various reasons, they struggle to get that reading done. #Read21in21 is meant to help form and strengthen the habit of reading.

April 2021 Reading:Wystan and Chester: A Personal Memoir of W. H. Auden and Chester Kallman by Thekla Clark, James Fenton (Amazon, Bookshop) -- I hunted down this memoir because in another book, I came across the anecdote that when W. H. Auden visited Bernard Berenson at I Tatti, he commented "how perfect everything was and how he longed to slip a satin pillow with ‘Souvenir of Atlantic City’ into the place.” So of course I had to look that up.

Beneficence by Meredith Hall (Amazon, Bookshop) -- Best Book of the Year by Kirkus and BookSense, Elle's “Readers' Pick of the Year." A friend gave this novel her highest praise. A solemn, thoughtful book about the nature of love, marriage, family, and perspective.

Life Is Short, Don't Wait to Dance: Advice and Inspiration from the UCLA Athletics Hall of Fame Coach of 7 NCAA Championship Teams by Valorie Kondos Field (Amazon, Bookshop) -- Another recommendation from a friend. Elizabeth and I talked about an idea from this book, "Ask for a favor in the right way," in episode 321 of the Happier podcast.

A Mathematician's Apology by G.H. Hardy (Amazon, Bookshop) -- Mary Karr recommended this memoir in her book The Art of Memoir (Amazon, Bookshop). A very unusual account of a vocation.

Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World by Haruki Murakami (Amazon, Bookshop) -- 1985 Tanizaki Prize. My daughter Eleanor is on a serious Murakami kick, so I decided to re-read this one so we could talk about it. Such an interesting novel.

Speak, Memory by Vladimir Nabokov (Amazon, Bookshop) -- Another re-read. A brilliant memoir, and so much about the five senses. Also recommended by Mary Karr.

The Opposite of Fate: Memories of a Writing Life by Amy Tan (Amazon, Bookshop) -- I loved this book of essays.

Ramona and Her Father by Beverly Cleary (Amazon, Bookshop) -- Newbery winner. Read in honor of the late Beverly Cleary! So, so, so good. This novel is notable because it deals with Ramona's father losing his job.

The Complete Greek Tragedies Vol. 3 by Euripides, edited by David Grene and Richmond Lattimore (Amazon) -- I re-read one play, The Bacchae. I'd listened to an episode of the In Our Time: Culture podcast about the play, which made me want to re-read it. I'd forgotten how absolutely extraordinary it is. It extends out in every direction, without end.

Burn by Patrick Ness (Amazon, Bookshop) -- I loved this young-adult novel: dragons, fate, prophecy, romance, courage, and more.

I Can Hear You Whisper: An Intimate Journey through the Science of Sound and Language by Lydia Denworth (Amazon, Bookshop) -- I've been thinking a lot about the sense of sound, so was very eager to read this account written by a friend.

The Dyer's Hand by W.H. Auden (Amazon, Bookshop) -- I loved these essays (except the ones that bored me, which I skipped).

Where the Past Begins: A Writer's Memoir by Amy Tan (Amazon, Bookshop) -- More Amy Tan! I'm a fan.

James Baldwin: The Last Interview and Other Conversations by James Baldwin, Quincy Troupe (Amazon, Bookshop) -- I'm a huge fan of the work of James Baldwin, and he's also very interesting in interviews. This book collects some of the most notable.

The Debt to Pleasure by John Lanchester (Amazon, Bookshop) -- 1996 Whitbread Book Award, 1997 Hawthornden Prize. A re-read. This is one odd, enjoyable novel! I highly recommend it, if you're the kind of person who likes this sort of thing. And I can't reveal exactly what kind of thing that is—spoilers. Also, lots about the five senses, especially taste and smell.

How Y'all Doing?: Misadventures and Mischief from a Life Well Lived by Leslie Jordan (Amazon, Bookshop) -- A delightful book of essays by the exuberant Leslie Jordan. Elizabeth and I had a great time interviewing him in episode 322 of the Happier podcast.

Life After Deaf: My Misadventures in Hearing Loss and Recovery by Noel Holston (Amazon, Bookshop) -- A fascinating account of how Holston coped with his sudden loss of hearing.

On Lighthouses by Jazmina Barrera (Amazon, Bookshop) -- A thought-provoking series of essays on the subject of lighthouses (and much more).

The Words: The Autobiography of Jean-Paul Sartre by Jean-Paul Sartre (Amazon, Bookshop) -- An extremely unusual and compelling memoir. Very honest, in an unusual way. Or was it honest? Fascinating to contemplate.

April 29, 2021

Bruce Handy: “Contemporary Life Demands Too Much Concentration; Not Concentrating Can Be Liberating.”

Interview: Bruce Handy.

Bruce Handy is an author, journalist, essayist, critic, humorist, and editor. He's the author of Wild Things: The Joy of Reading Children’s Literature as an Adult (Amazon, Bookshop). I'm a huge fan of children's literature, and I absolutely love Bruce's book. I wish he'd write Volume II, Volume III, Volume IV...

Bruce has also worked as a writer-editor at Vanity Fair, Time, Esquire, and Spy and has contributed to the New York Times Magazine, the New York Times Book Review, New York, the New Yorker, The Atlantic and the Wall Street Journal.

Bruce's new book is The Happiness of a Dog With a Ball in Its Mouth (Amazon, Bookshop), which is his first book for young readers. I also love picture books, so I was very excited to read his latest work.

I couldn't wait to talk to Bruce about creativity, habits, and of course, children's literature.

Gretchen: What’s a simple activity or habit that consistently makes you happier, healthier, more productive, or more creative?

Bruce: For me, any activity that allows my mind to wander stimulates creativity, from which those other attributes tend to flow. Running, for instance. I don’t listen to anything when I run and I mostly follow the same route every day, which is maybe boring but allows me not to concentrate on anything in particular. The same with long showers. Or, best of all, stirring from sleep but not getting out of bed. A lot of ideas come to me when I’m in that half-awake state. Sometimes it feels like productive dreaming—which as I write that phrase strikes me as kind horrible, like I’ve taking something lovely and ineffable and harnessed it to utilitarian ends, but half-wakefulness works for me, and has the added benefit of justifying what might look like laziness to some. (Needless to say, my children are no longer school age.) Contemporary life demands too much concentration; not concentrating can be liberating.

What’s something you know now about happiness that you didn’t know when you were 18 years old?

I think, at eighteen, I thought happiness came in one size. I now know it comes in many sizes, shapes, wrappings, payment plans, etc.

Have you ever managed to gain a challenging healthy habit – or to break an unhealthy habit? If so, how did you do it?

I quit cigarettes in my late twenties, after smoking for ten or so years--starting in college was the stupidest thing I ever did. I was lucky in that I was able to quit cold turkey without too much stress, largely because I had become disgusted by it. I guess the disgust outweighed the addiction. It helped that I had adopted healthier habits earlier in my twenties, like running and not having potato salad for lunch every day; I think I was twenty-four when I realized I was going to have to start working at it if I didn’t want to turn into a blob. The funny thing is, there were maybe three years where I was both running and smoking. How did I manage that?

Would you describe yourself as an Upholder, a Questioner, a Rebel, or an Obliger?

I see elements of myself in all four, but professionally I’m a Questioner. [Note from Gretchen: Seeing yourself in all four Tendencies is itself a sign of Questioner.

Is there a particular motto or saying that you’ve found very helpful?

There is a jazz musician named Matt Wilson, a drummer, whose music I love—his playing is smart, witty, and joyous. He suffered some horrible losses in his private life, but in 2012 he released an album called “An Attitude for Gratitude.” I saw his group perform that year and he passed out purple plastic bracelets with the title on them. I’ve worn mine ever since, even though the words wore off years ago, as a reminder to be grateful. So much flows from gratitude.

Has a book ever changed your life – if so, which one and why?

Where the Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak (Amazon, Bookshop). I didn’t like that book as a kid; I just thought it was weird. But when I rediscovered it as a parent, I found it spoke to me—it made sense to me at thirty-eight in a way that, at six, it didn’t. I wrote an essay about that, which led to writing a whole book about reading children’s literature as an adult, which in turn has let me to write actual children’s books. I suspect it’s unusual to publish your first kids’ book at sixty-two, but it took decades to accrue the kind of emotional clarity writing for kids requires, at least for me. (PS: There’s nothing wrong with not liking Where the Wild Things Are, as either a kid or an adult. People of any age should never feel bad for liking what they like, unless we’re talking about anti-social behaviors.)

Author photo by Justin Bishop.

April 27, 2021

We’re Happier When We Keep a Sense of Perspective, But How? Here Are a Few Ideas.

From my long study of happiness, and from my own experience, I've learned the importance of keeping a sense of perspective. When I take the long view, my own worries seem smaller. Circumstances seem less dire. I'm more aware of positive change. I don't take myself so seriously.

But in the tumult of everyday life, I often find it hard to keep a sense of perspective.

As I was brushing my teeth this morning, I realized that I'd discovered a hack that helps me keep a sense of perspective, without realizing that I was using it.

I listen to the BBC 4's In Our Time podcast. This podcast is really five separate podcasts: In Our Time: History, In Our Time: Philosophy, In Our Time: Religion, In Our Time: Science, and In Our Time: Culture.

I listen to these episodes when I want a sense of thoughtful calm. I learn a lot, of course, but I get something more. I'm reminded of the long, slow sweep of history; the vastness and mysteries of nature; and the greatness and strangeness of human creation. I'm reminded of how little I know, and how much I want to learn.

It comforts me to learn that Alcuin of York was a scholar of such renown that he's remembered to this day—yet he didn't know the concept of zero and did his calculations using Roman numerals.

And I experience moments of transcendence. In the discussion of Euripides's masterpiece, the tragedy The Bacchae, the panelist comments, "Right at the end, there's that chilling line by Cadmus, 'You've gone too far; it's not right for you to show so much anger,' and Dionysus says, 'But all of this Zeus agree to long ago.'" (at 50:55). As I heard her repeat those words, the hair stood up on the back of my neck. I stopped the podcast to think about that line; then replayed it three times; and later that week re-read the entire play.

I wanted to learn more about the background of the show, and I found this terrific review in the New Yorker by Sarah Larson. Turns out, she had found the same sense of perspective that I do. As she puts it:

In part because "In Our Time" is unconnected to things that are coming out, things happening right this minute...it feels aligned with the eternal rather than the temporal, and is therefore escapist without being junk.

I also get a sense of perspective from my daily visits to the Metropolitan Museum. Entering the Great Hall shrank my everyday worries and preoccupations to their proper size.

The museum fills me with transcendent feelings of permanence, preservation, scholarship, reverence. I feel smaller and also larger. Time seems to pause, to give me an expansive sense of possibility, because the Met is a place outside of time, where objects from the distant past and recent times mix under one roof. On the labels, I read about whole empires that rose, fell, and are now forgotten.

How do you find a sense of perspective these days?

April 23, 2021

Have You Experienced Changes to Your Sense of Smell?

For my book about my five senses, I've been thinking a lot about the sense of smell. How I love the sense of smell! One of my favorite Happier at Home resolutions was to "Cultivate good smells." It's astonishing to me how much pleasure certain scents give me, now that I've tuned into them more forcefully.

In the past, people often took the sense of smell for granted; because it’s invisible and fleeting, it’s easy to underrate it. But smell isn’t just some sort of bonus sense—it plays a vital role in helping us to feel connected to others and to the world.

These days, though, I think that people are far less likely to take the sense of smell for granted. Due to the pandemic, many people's sense of smell has been altered or lost—temporarily or perhaps permanently. And because the sense of smell is crucial for the sense of flavor, losing smell also meant that food and drink lost much of their appeal.

A friend temporarily lost her sense of smell from COVID-19. When I asked her about it, she said, “I felt claustrophobic. The world felt stale and airless, nothing registered.” (Thankfully, her sense of smell has returned.)

During the time that she couldn't smell, my friend drank a lot of kombucha, because it gave her some kind of sensations that registered.

If you experienced a change to your sense of smell—whether from COVID-19 or for some other reason—what was your experience? Did you find any strategies to help register sensation (such as drinking kombucha)?

If you'd like to read or listen to an engrossing discussion of this subject, I recommend "The Forgotten Sense: What Can COVID-19 Teach Us About the Mysteries of Smell?" by Brooke Jarvis in the New York Times. It explores our sense of smell, and how the coronavirus has affected so many people’s sense of smell—and how we’re now so much more aware of the value of this sense. (Thanks to the many thoughtful listeners who sent me the link to this piece, because they rightly guessed that I'd find it fascinating.)

I'm a big fan of the writing of Leslie Jamison, and I was fascinated by her haunting account of losing her sense of smell from COVID-19. (Her sense of smell did return.)

These accounts underscore how crucial our sense of smell is—to our sense of vitality and engagement.

April 22, 2021

Gina Hamadey: “A Gratitude Habit Does Not Mean Pasting a Smile Atop Your Misery.”

Interview: Gina Hamadey

Gina Hamadey was the travel editor at Food & Wine and Rachael Ray Every Day and started her career at the O, the Oprah Magazine, and George. She founded the content and social strategy firm Penknife Media, and has written for The New York Times, Real Simple, and Women’s Health, among other publications.

Her new book, I Want to Thank You: How a Year of Gratitude Can Bring Joy and Meaning in a Disconnected World (Amazon, Bookshop), chronicles her year writing 365 thank-you notes to friends, family, strangers, neighbors and more. .

I couldn't wait to talk to Gina about happiness, habits, and gratitude.

Gretchen: What’s a simple activity or habit that consistently makes you happier, healthier, more productive, or more creative?

Gina: Writing thank you notes and gratitude letters. In 2018 I sent out 365 gratitude notes to friends, family, neighbors and strangers. Every month I turned to a new group of recipients, including career mentors, favorite authors and healthcare workers. Most of these notes were not very long (some were written on postcards)—three or four heartfelt, specific sentences. Writing heartfelt gratitude notes feels like a combination of meditation and therapy: My breathing and heart rate slows down (there are scientific studies that show that to be true), and a calm, meditative focus comes over me.

Here’s the story of how I launched what I call my Thank You Year: I had just finished a batch of thank you notes to donors to my City Harvest fundraiser, and I was surprised at how good that process felt. I was sitting on the train reflecting on that, and noticed that I had written 31 cards, one for every day so far. What if I kept it up?

While I am no longer keeping up that one-a-day pace—technically I would write 10 or 15 at a time, but you get the idea—I still sit and write a note of gratitude when I want that dose of calm, joyful focus. And that year trained me to recognize grateful thoughts, hold onto them a little longer, and share them with the people responsible—if not in a letter, then via text or email or in person. That habit has made me a happier person.

What’s something you know now about happiness that you didn’t know when you were 18 years old?

The way you speak to yourself matters. This might be embarrassing, but I often use terms of endearment when I talk to myself, which I do in the second person (apparently not all that common?). “Okay, honey, you can do this.” “You’ve got this, babe.”

You’ve done fascinating research. What has surprised or intrigued you—or your readers—most?

In the year I sent out 365 gratitude notes, I was surprised at how frequently I heard something along the lines of, “I am going through a hard time, and this helped.” By approaching people in this vulnerable way—it’s not cool, telling someone you haven’t seen in years that you still think about them—I made space for them to respond in kind.

Also, I expected or at least hoped that writing these notes would get me back in touch with people I hadn’t spoken to in awhile. I was surprised at how powerful it was to express gratitude to the people closest to me, including my husband, to whom I wrote a thank you note every day for a month.

Have you ever managed to gain a challenging healthy habit – or to break an unhealthy habit? If so, how did you do it?

As the former travel editor at Food & Wine and Rachael Ray’s magazine, a huge part of my identity has been tied up in food and booze—being able to sample anything and everything and have an opinion on it. As I approached 40, that approach wasn’t working for me anymore. The biggest sign was, oddly, my eyes, which were inflamed to such a degree that I couldn’t wear contacts for nine months, and I needed to take a heavy dose of antibiotics. I started experimenting with my diet and realized that I don’t do well with gluten, sugar or dairy. Dairy! I wrote a nacho cookbook! But once I started feeling better—more energy, better sleep, brighter skin—those changes really haven’t been so difficult to stick to. I attribute my resilient attitude to my Thank You Year. Instead of pining for pasta and ice cream, I am focused on the health benefits and all the foods I am still able to enjoy (guacamole, steak, French fries with mayo).

Would you describe yourself as an Upholder, a Questioner, a Rebel, or an Obliger?

I’m an Upholder. How else would I have stuck to sending out 365 gratitude notes in a year when I had a full roster of clients and two kids four and under?

Is there a particular motto or saying that you’ve found very helpful? Or a quotation that has struck you as particularly insightful?

“Happiness is equilibrium. Shift your weight.” That’s from Tom Stoppard’s The Real Thing, which was, I believe, the first play I saw on Broadway after moving to New York at 21 years old, so it made a real impression. I think about that quote all the time. If I’m feeling down, what am I missing—time with friends, or by myself, or with a good book? Have I exercised, and hydrated, and slept?

The day that I came up with the concept of the Thank You Year on the train, I wondered whether the timing was right for this project, what with a busy docket of clients and two kids at home who were four and one. The reason that I did it anyway was because of that concept. I felt like I was operating in triage, tending to the neediest client or child or bill, and I wanted to find a way to reconnect to the parts of myself that were left behind. I was intentionally shifting my weight.

Has a book ever changed your life – if so, which one and why?

I read both Jane Goodall’s Harvest for Hope: A Guide to Mindful Eating (Amazon, Bookshop) and Barbara Kingsolver’s Animal, Vegetable, Miracle (Amazon, Bookshop) in 2007 with my food-related book club, and those books changed the way I grocery shopped and cooked. This was before “local” and “sustainable” were in the public lexicon, and I remember feeling embarrassed that I hadn’t before given thought to the provenance of my food—and I worked at a food magazine! We still plan our weekly meals around our Sunday farmer’s market visits thanks to that mindset change.

In your field, is there a common misconception that you’d like to correct?

Gratitude does not equal toxic positivity, to use a term that’s trending on Instagram. A gratitude habit does not mean pasting a smile atop your misery. You can feel all human feelings—rage, despair—and then return to a gratitude practice that helps you see what’s beautiful and joyful, and appreciate the people who make your life better. Gratitude is powerful medicine.

April 20, 2021

Are You a “Foodie?” I Have to Admit: I’m Not.

I’ve never been much of a foodie.

I love learning about the sense of taste for my five-senses book, and I love certain foods, but I like very plain food best, like scrambled eggs or fish without sauce. I like my coffee mild and my meat cooked through. I don’t get much of a kick from visiting new restaurants, eating elaborate meals, exploring farmers’ markets, or learning about foods’ origins or cooking techniques.

And once I quit sugar, I became even less passionate about food.

One of the sad aspects of a happiness project, for me, is to Be Gretchen and to admit this aspect about my nature.

My lack of enthusiasm makes me feel like a killjoy; a love for food is a marker of a love for life. Cooking expert Julia Child, who's one of my patron saints, declared, “People who love to eat are always the best people”; food essayist Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin wrote, “Tell me what you eat, and I shall tell you what you are.” What does that say about me?

But over the years of writing about happiness and human nature, I've learned that usually when I think, "I'm the only one," it turns out I'm not the only one.

I thought I was the only one who was an "Abstainer."I thought I was the only one who was an under-buyer.I thought I was the only one who was comforted by routines and rigidity.When I shared my experiences, other people said they knew exactly what I was talking about. And I realized that if I'd been paying attention, I would've realized long ago that I wasn't the only one.

So...am I the only one who's not much of a foodie? What's your experience? Or are you a tremendous foodie? I'd be interested to hear about that, too.

April 16, 2021

When I’m Anxious, I Turn Off the Music. Do You Do Something Similar?

Recently, I realized something about myself.

When I'm feeling anxious, I often respond by turning down some sensation. For instance, during the most intense part of the pandemic shut-down, I stopped wearing perfume or lighting scented candles—and I was puzzled by my own reaction.

Then, as I thought about it, I realized when my daughter Eleanor was playing music in the kitchen, I'd ask her to turn it off.

I wouldn’t be feeling particularly anxious, but suddenly, the extra scent or sound seemed like too much.

It took me some time to realize that this habit was my “tell.” In gambling, a tell is a change in behavior that reveals a person’s inner state, and gamblers look for tells as clues about whether other players are holding good or bad hands.

I knew that one of my tells is that when I’m feeling worried, I re-read my favorite works of children’s literature, because I want the coziness and familiarity of a book I love.

Now I’ve identified a new tell.

I’ve only recently realized this habit in myself, and I'm curious—do other people do this, too?

For instance, I recently got this email:

I had been a dedicated listener of the Happier podcast for a long time, until the Covid shutdown, when, bizarrely, I stopped listening to all podcasts. I’m still not sure why I stopped listening, but I’m so glad that I resumed listening to your show.

How about you? When you're feeling anxious or overwhelmed, do you try to change your environment in some way?