Corey Robin's Blog, page 52

January 24, 2016

On Ta-Nehisi Coates, Cass Sunstein, and Other Public Intellectuals

I have a long piece up at The Chronicle Review on public intellectuals. It’s an adaptation of the keynote address I gave last fall at the Society of US Intellectual History. Here are some excerpts…

What is a public intellectual?

As an archetype, the public intellectual is a conflicted being, torn in two competing directions.

On the one hand, he’s supposed to be called by some combination of the two vocations Max Weber set out in his lectures in Munich: that of the scholar and that of the statesman. Neither academic nor activist but both, the public intellectual is a monkish figure of austere purpose and unadorned truth. Think Noam Chomsky.

On the other hand, the public intellectual is supposed to possess a distinct and self-conscious sense of style, calling attention to itself and to the stylist. More akin to a celebrity, this public intellectual bears little resemblance to Weber’s man of knowledge or man of action. He lacks the integrity and intensity of both. He makes us feel as if we are in the presence of an actor too attentive to his audience, a mind too mindful of its reception. Think Bernard-Henri Lévy.

Yet that attention to image and style, audience and reception, may not only be not antithetical to the vocation of the public intellectual; it may actually serve it. The public intellectual stands between Weber’s two vocations because he wants his writing to do something in the world. “He never wrote a sentence that has any interest in itself,” Ezra Pound said of Lenin, “but he evolved almost a new medium, a sort of expression halfway between writing and action.”

The public intellectual is not simply interested in a wide audience of readers, in shopping her ideas on the op-ed page to sell more books. She’s not looking for markets or hungry for a brand. She’s not an explainer or a popularizer. She is instead the literary equivalent of the epic political actor, who sees her writing as a transformative mode of action, a thought-deed in the world. The transformation she seeks may be a far-reaching change of policy, an education of manners and morals, or a renovation of the human estate. Her watch may be wound for tomorrow or today. But whatever her aim or time frame, the public intellectual wants her writing to have an effect, to have all the power of power itself.

To have that effect, however, she must be attuned to the sensitivities of her audience. Not because she wishes to massage or assuage them but because she wants to tear them apart. Her aim is to turn her readers from what they are into what they are not, to alienate her readers from themselves….

Though the public intellectual is a political actor, a performer on stage, what differentiates her from the celebrity or publicity hound is that she is writing for an audience that does not yet exist. Unlike the ordinary journalist or enterprising scholar, she is writing for a reader she hopes to bring into being. She never speaks to the reader as he is; she speaks to the reader as he might be. Her common reader is an uncommon reader.

On Cass Sunstein

With all his talk of menus and default settings, Sunstein is aiming for a new kind of politics, where government, as he and Thaler write, is “both smaller and more modest.” This new politics “might serve as a viable middle ground in our unnecessarily polarized society.” It “offers a real Third Way — one that can break through some of the least tractable debates in contemporary democracies.” Sunstein is also aiming for a new self. There are two types of souls in the world, he and Thaler say: Econs and Humans. What distinguishes them is the ability to secure the ends they seek. Econs have a lot of instrumental rationality and are rare; in fact, they don’t exist at all, except in economics journals. Humans have very little of it. The goal of politics is to bring these real, all too real, Humans into some kind of alignment with these fictitious Econs.

It is that desired transformation — of the self, and of the society in which the self becomes a self — that marks Sunstein as a public intellectual. And marks the ground of his failure. For the polity Sunstein would like to bring into being looks like the polity that already exists. Its setting is the regulatory state and capitalist economy we already have. Its ideology is the market fundamentalism we already pay obeisance to: “a respect for competition,” Sunstein stipulates, “is central to behaviorally informed regulation.” And its actors are the consumers we already are.

Consumers, as Sunstein’s utopia makes clear, with no need for a public. In decades to come, Sunstein writes, the choice architect “might draw on available information about people’s own past choices or about which approach best suits different groups of people, and potentially each person, in the population.” So finely tuned to each of our needs will this future choice architect be that “personalized paternalism is likely to become increasingly feasible over time.” Whatever libertarian slippage may be occasioned by the current state of choice architecture — where some serendipity of desire is eclipsed or ignored by the crude technology of the day — will be overcome in the future. Assured by the detailed knowledge the choice architect will have about each of us, each of us will be happily corrected in our choices. We will know that these are truly our choices, inspired by our ends, uncontaminated by anyone else. What we are witnesses to here is not a public being summoned but a public being dismissed.

…

Set against Sunstein’s nudge, Wickard v. Filburn reads like the lost script of an ancient civilization. Across-the-board mandates like that farm quota, which affect everyone regardless of individual circumstance, are the other of nudge politics precisely because they affect everyone regardless of individual circumstance. But that is their public power: They create a commons by forcing a question on everyone with no opt-out provisions of the sort that Sunstein is always on the lookout for. By requiring economic actors to think of themselves as part of a class “of many others similarly situated,” by recasting a private decision to opt out of the market as a choice of collective portent, mandates force men and women to think politically. They turn us into a public.

That’s also how public intellectuals work. By virtue of the demands they make upon the reader, they force a reckoning. They summon a public into being — if nothing else a public conjured out of opposition to their writing. Democratic publics are always formed in opposition and conflict: “to form itself,” wrote Dewey, “the public has to break existing political forms.” So are reading publics. Sometimes they are formed in opposition to the targets identified by the writer: Think of the readers of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring or Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow. Sometimes they are formed in opposition to the writer: Think of the readers of Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem. Regardless of the fallout, the public intellectual forces a question, establishes a divide, and demands that her readers orient themselves around that divide.

It is precisely that sense of a public — summoned into being by a writer’s demands; divided, forced to take sides — that Sunstein’s writing is in flight from. And not just Sunstein’s writing but the vast college of knowledge from which it emanates and the polity it seeks to insinuate.

On Ta-Nehisi Coates

Anyone familiar with Ta-Nehisi Coates will come to Between the World and Me with great expectations: of not only its author’s formidable mind and considerable gifts but also of a public not often present in contemporary culture. From his blog, articles, and engagement with critics high and low, we know that Coates is a writer with an appetite and talent for readers. And not just any readers but readers hungry for the pleasure of prose and the application of intelligence to the most fractious issues of the day.

Anyone who has read Between the World and Me will find those expectations fulfilled. The first page opens with the body, the last closes with fear. From Machiavelli to Judith Shklar, the body and fear have been touchstones of our modern political canon. Given this marriage of talent and topic, we have every reason to receive Between the World and Me as a major intervention in public life and letters, as perhaps the signal text of today’s civic culture.

Yet it is the very presence of those political themes — the body and fear — that should make us wary. For Coates writes against the backdrop of a long tradition replete with cautionary tales about what can happen to public argument when the terrorized body becomes the site of moral inquiry.

At one pole of that tradition stands Hobbes, who more than anyone made that body the launching point of his inquiry; the end point, as readers of Leviathan know, was the obliteration of politics and the public. Only a sovereign capable of settling all questions of moral and political dispute, and enforcing his judgments without resistance, could provide the body the protection, the relief from fear, it needed.

At the other pole of that tradition stands Marx, who understood the body, laboring in the factory, as the site of a civilizational conflict over human domination and the ends of human existence. Where Hobbes saw in the body a set of claims that might annihilate politics and the public for the sake of peace and security, Marx saw in the body a set of claims that might launch an entirely new form of politics, a new public, into being.

Where between — or beyond — these poles does Coates stand?

For some, the very question will seem like an offense. Here is an African-American writer navigating the African-American experience of white despotism: What has he to do with Hobbes or Marx? Surely a book that begs to be read outside the white gaze has earned its right to autonomy, to be free of the judgments of the white Euro-American canon.

We should resist that move. There’s an unsettling tendency, particularly among white liberal readers, to treat black writers, and the black experience, as somehow sui generis, as standing completely apart from other parts of the culture.

…

Despite Coates’s atheism and the science of global warming that underlies this vision of destruction, it’s hard to escape its theological overtones. Baldwin derived the title of The Fire Next Time from the couplet of a black spiritual: “God gave Noah the rainbow sign./ No more water, the fire next time.” The couplet is a more menacing rendition of the original story in Genesis 9. After the Flood, God promises Noah that he will never again destroy humanity and that the rainbow will be a sign of God’s covenant with humanity. But the spiritual Baldwin cites warns of a different ending: This time, it was the flood; next time, it will be the fire. Though The Fire Next Time was written in 1962, it’s hard not to read it as a premonition of the urban fire that would consume America later that decade.

Coates writes out of an even stronger atheism than Baldwin, yet he conjures a catastrophe more biblical and otherworldly than anything Baldwin, who was reared and steeped in the teachings of the black church, imagined. Baldwin envisioned not a flood but a fire, a fire set by men against men. For Coates, it is the opposite: no more fire, the water next time.

So there will be a rescue from the sky, of sorts. Black America will be delivered by a sovereign from above. Its suffering will come to an end. Only it will end the way all living things come to an end: by death. The answer to black suffering is not a public roused, but as was true of Hobbes, a public annihilated.

Whither Public Intellectuals?

We have the means, we have the material. What we don’t have is mass. We have episodic masses, which effervesce and overflow. But it’s hard to imagine masses that will endure, publics that won’t disappear in the face of state repression or social intransigence but instead will dig in and charge forward. And it is that constraint on the imagination and hence the will that is the biggest obstacle to the public intellectual today. Not tenure, not the death of bohemia, not jargon, but the fear that the publics that don’t yet exist — which are, after all, the only publics we’ve ever had — never will exist.

January 23, 2016

Clinton’s Firewall in South Carolina is Melting Away…

In my last post, I talked about the liberal pundits who see black voters as “Hillary’s Firewall.” Even if Sanders wins in states like Iowa and New Hampshire, which have large white populations, the pundits say he’ll find his support plummeting in a state like South Carolina, where black voters are firm Clinton supporters. I pointed out that in 2008, Clinton saw that firewall in South Carolina quickly melt after Obama’s victory in Iowa and his strong second-place finish in New Hampshire. I also pointed out that South Carolina representative Jim Clyburn, who is African American and one of the top Democrats in the House, was cautioning against the notion that black voters were solidly behind Clinton this time around.

Turns out, he was right. According to a poll released yesterday, support for Clinton in South Carolina is plummeting. Back in December, Clinton had a 36-point lead over Sanders. As of yesterday, that lead has been cut nearly in half. 47% of Democratic voters now favor Clinton; 28% favor Sanders. That’s still a lot of support for Clinton, but it’s considerably smaller than in December, when she had 67% of the vote.

Now it’s true that Sanders hasn’t gotten those defectors from Clinton. What seems to have happened is that a significant chunk of her supporters are reconsidering their support (Sanders’s support is nearly what it was in December). Which could mean many things. One possibility is that voters are waiting to see what happens in Iowa and New Hampshire, where Sanders is doing well.

But the most interesting part of the polls is the racial and gender breakdown of the vote: Clinton is losing a higher percentage of her black supporters than of her white supporters, and Sanders is making greater gains among women than among men.

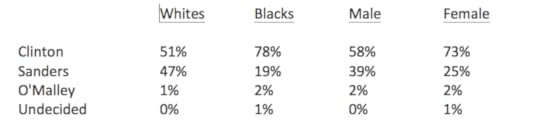

On December 17, this is how the polls looked (see the thirteenth page, which is labeled page six):

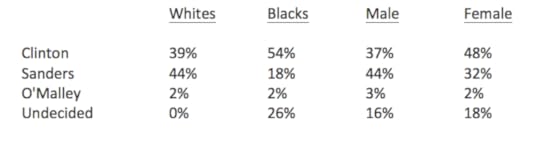

On January 22 (the poll was actually concluded on the 15th), this is how the polls looked:

Between December and January, we see major drops in support for Clinton among all categories of voters. But there’s a greater drop among black voters (30%) than among white voters (24% drop). There’s also a virtually identical drop among male (36%) and female (34%) voters.

Sanders’s support among black voters remains practically the same as it was in December (he sees a tiny drop among white voters). But more interesting is that while he’s made gains among both male and female voters, the gains among women (28%) are much greater than among men (13%).

H/t Alex Gourevitch, Arin Dube, and Seth Ackerman for pointing me to these polls.

January 22, 2016

Bile, Bullshit, and Bernie: 16 Notes on the Democratic Primary

For the last two weeks or so, I have been trying to stay focused on my work on Clarence Thomas, but all the liberal commentary on the Democratic primary has gotten me so irritated that I keep finding myself back on social media, posting, tweeting, commenting, and the like. So I figured I’d bring everything that I’ve been saying about the election campaign there, here. In no particular order.

1. Clintonite McCarthyism

According to The Guardian:

The dossier, prepared by opponents of Sanders and passed on to the Guardian by a source who would only agree to be identified as “a Democrat”, alleges that Sanders “sympathized with the USSR during the Cold War” because he went on a trip there to visit a twinned city while he was mayor of Burlington. Similar “associations with communism” in Cuba are catalogued alongside a list of quotes about countries ranging from China to Nicaragua in a way that supporters regard as bordering on the McCarthyite rather than fairly reflecting his views.

This is becoming a straight-up rerun of the 1948 campaign against Henry Wallace. Except that Clinton is running well to the right of Truman and even, in some respects, Dewey. It seems as if Clinton is campaigning for the vote of my anticommunist Grandpa Nat. There’s only one problem with this strategy: he’s been dead for nearly a quarter-century.

As was true of McCarthyism, it’s not really Sanders’s communism or his socialism that has got today’s McCarthyites in the Democratic Party worried; it’s actually his liberalism. As this article in the Times makes clear:

“Some third party will say, ‘This is what the first ad of the general election is going to look like,’” said James Carville, the longtime Clinton adviser, envisioning a commercial savaging Mr. Sanders for supporting tax increases and single-payer health care. “Once you get the nomination, they are not going to play nice.”

…

A Sanders-led ticket generates two sets of fears among Clinton supporters: that other Democratic candidates could be linked to his staunchly liberal views, particularly his call to raise taxes, even on middle-class families, to help finance his universal health care plan; and that more mainstream Democrats would have to answer to voters uneasy about what it means to be a European-style social democrat.

Raising taxes to pay for popular middle-class programs: that used to be the bread and butter liberalism of the Democratic Party. Now it’s socialism.

2. Clinton’s “Firewall”

The new line of argument against Sanders winning the nomination is that African American voters are Clinton’s “firewall,” which will engulf the Sanders campaign once it heads South. There have been God knows how many articles making this claim over the last two days, celebrating both Clintons’ deep and storied relations with the black community—how, whatever the Clintons’ policy positions (support for mass incarceration, welfare reform, etc.), they do the kind of retail and symbolic politics that black voters care most about. (I’ll note in passing but not comment on the patronizing condescension of this position). And that we’ll see all of this come into play after Iowa, when the campaign heads to South Carolina.

So let’s go to the Wayback Machine and see how black leaders in South Carolina responded in 2008 to the last time the Clintons worked their magic there:

“Black leaders widely criticized Mr. Clinton after he equated the eventual victory of Mr. Obama in the South Carolina primary in January to that of the Rev. Jesse Jackson in the 1988 caucus, a parallel that many took as an effort to diminish Mr. Obama’s success in the campaign….In an interview with The New York Times late Thursday, Mr. Clyburn [3rd ranking member of the House] said Mr. Clinton’s conduct in this campaign had caused what might be an irreparable breach between Mr. Clinton and an African-American constituency that once revered him.

Speaking of Jim Clyburn and South Carolina, he was on NBC recently, talking about Clinton’s firewall. Start listening at 2:30, where he says that if Sanders wins by ten points in Iowa, that firewall could disappear very quickly. As it did in 2008.

3. Sister Souljah Moment

Remember Sister Souljah? In 1992, Bill Clinton chose to go after her as a signal to white voters that he and the Democrats were not beholden to black voters. It was a signature moment not only for him but also for the Democratic Party: they weren’t going to be the party of quotas, welfare, and black people. Which makes the claim that Sanders is bad on race all the more galling. Have we forgotten everything? Well, there’s one figure in the United States today who hasn’t: Sister Souljah. Back in November, she spoke out against Clinton’s campaign.

3. A Little Nutty and a Little Slutty

David Brock, the man who called Anita Hill “a little bit nutty and a little bit slutty,” now says “black lives don’t matter much to Bernie Sanders.” Brock is described here as “a top Clinton ally” who “runs several super PACs aiding her candidacy.”

4. Dissolve the People, Elect Another

As Sanders surges in the polls in Iowa and New Hampshire—opening up a 8-point lead in Iowa and a 27-point lead in New Hampshire—and the pundits and party elites get squirmier and squirmier about his possible victory, I’m reminded of this line from Brecht:

Would it not be easier

In that case for the government

To dissolve the people

And elect another?

5. Camera Obscura

Speaking of German writers, in The German Ideology, Marx wrote, “In all ideology men and their circumstances appear upside-down as in a camera obscura.” I was reminded of that quote when I stumbled across this story from the summer. Back in July, while everyone was touting Clinton’s sensitivity and deftness (and Sanders’s insensitivity and tone-deafness) around issues of mass incarceration and Black Lives Matter, this little tidbit was reported in The Intercept. And completely ignored:

Lobbyists for two major prison companies are serving as top fundraisers for Hillary Clinton….Richard Sullivan, of the lobbying firm Capitol Counsel, is a bundler for the Clinton campaign, bringing in $44,859 in contributions in a few short months. Sullivan is also a registered lobbyist for the Geo Group, a company that operates a number of jails, including immigrant detention centers, for profit. As we reported yesterday, fully five Clinton bundlers work for the lobbying and law firm Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld. Corrections Corporation of America, the largest private prison company in America, paid Akin Gump $240,000 in lobbying fees last year. The firm also serves as a law firm for the prison giant, representing the company in court….The Geo Group, in a disclosure statement for its investors, notes that its business could be “adversely affected by changes in existing criminal or immigration laws, crime rates in jurisdictions in which we operate, the relaxation of criminal or immigration enforcement efforts, leniency in conviction, sentencing or deportation practices, and the decriminalization of certain activities that are currently proscribed by criminal laws or the loosening of immigration laws.”

Apparently, the new rule of American politics is: So long as you say the right thing, you can do anything.

Post-script: By October, the heat on Clinton over this issue had gotten to be so great—thanks in part to Black Lives Matter—that she was forced to stop working with these clowns from the prison industrial complex. And return all the money.

It should be noted that Sanders never had to return a dime. Because he never took a dime.

6. Reparations

Sanders has gotten a lot of heat from the left for saying he’s against reparations. Interestingly, in 2008, another presidential candidate was asked about his position on reparations. Here’s what he had to say:

Democratic presidential candidate Barack Obamaopposes offering reparations to the descendants of slaves, putting him at odds with some black groups and leaders.

The man with a serious chance to become the nation’s first black president argues that government should instead combat the legacy of slavery by improving schools, health care and the economy for all.

“I have said in the past — and I’ll repeat again — that the best reparations we can provide are good schools in the inner city and jobs for people who are unemployed,” the Illinois Democrat said recently.

…

“Let’s not be naive. Sen. Obama is running for president of the United States, and so he is in a constant battle to save his political life,” said Kibibi Tyehimba, co-chair of the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America. “In light of the demographics of this country, I don’t think it’s realistic to expect him to do anything other than what he’s done.”

But this is not a position Obama adopted just for the presidential campaign. He voiced the same concerns about reparations during his successful run for the Senate in 2004.

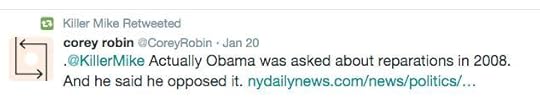

I pointed this out on Twitter to Killer Mike, the rapper who’s supporting Sanders. He retweeted me, which may be just about the biggest endorsement on Twitter I’ve ever gotten.

Except for that time Morgan Fairchild retweeted me. And that time John Cusack retweeted me. But who’s counting?

7. The Establishment

After Human Rights Campaign and Planned Parenthood endorsed Clinton, Sanders said they were part of “the establishment.” Clinton supporters made a big to do of it. But this response from Garance Franke-Ruta was the most sublime in its absurdity:

Bernie remarks a reminder how left economics & new social movements—civil rights, women’s rights, gay rights—have always been uneasy allies

— Garance Franke-Ruta (@thegarance) January 20, 2016

No, not really. Back in 1985, that old dinosaur of a socialist Bernie Sanders was signing a Gay Pride Day Proclamation on the grounds that gay rights were civil rights. Back in the 1990s, while the Clintons were supporting DOMA and Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell, that old dinosaur of a socialist helped lead the opposition to both policies on the grounds that they were anti-gay. And throughout his career in the Senate, Sanders got consistently higher ratings from civil rights organizations than Clinton did while she was a senator.

Again, the lack of memory among journalists is stunning.

Speaking of the establishment, Clinton is now claiming that it’s Sanders who’s the establishment, while she is, I don’t know what. Whatever she calls herself, I wonder what she calls this:

Hillary Clinton’s campaign released a letter this week in which 10 foreign policy experts criticized her opponent Bernie Sanders’ call for closer engagement with Iran and said Sanders had “not thought through these crucial national security issues that can have profound consequences for our security.”

The missive from the Clinton campaign was covered widely in the press, but what wasn’t disclosed in the coverage is that fully half of the former State Department officials and ambassadors who signed the letter, and who are now backing Clinton, are now enmeshed in the military contracting establishment, which has benefited tremendously from escalating violence around the world, particularly in the Middle East.

Here are some of the letter signatories’ current employment positions that were not disclosed in the reporting of the letter:

Former Assistant Defense Secretary Derek Chollet, former Pentagon and CIA Chief of Staff Jeremy Bash, and former Deputy National Security Adviser Julianne Smith are now employed by the consulting firm Beacon Global Strategies, a firm we profiled last year. Beacon Global Strategies’ staff advises both Clinton and Republican candidates for president, including Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio. The firm makes money by providing advice to a clientele that is primarily military contractors. Beacon Global Strategies, however, has refused to disclose the identity of its clients.

Former Undersecretary of State Nicholas Burns is a senior counselor at the Cohen Group, a consulting firm founded by former Defense Secretary William Cohen. The firm “assists aerospace and defense firms on policy, business development, and transactions,” including deals in the U.S., Turkey, Israel, and the Middle East.

Former Undersecretary of Defense Jim Miller is an advisory boardmember to Endgame Systems, a start-up that has been called the “Blackwater of Hacking.” Miller is also on the board of BEI Precision Systems & Space, a military contractor.

8. Idiot/Savant

You’ll be hearing a lot in the coming weeks about what a political savant Hillary Clinton is—and what a political naif Bernie Sanders is. You already have. On Sunday or Monday, I counted five such articles alone. Some information to consider when you hear that kind of talk:

Even though the Clinton team has sought to convey that it has built a national operation, the campaign has invested much of its resources in the Feb. 1 caucuses in Iowa, hoping that a victory there could marginalize Mr. Sanders and set Mrs. Clinton on the path to the nomination. As much as 90 percent of the campaign’s resources are now split between Iowa and the Brooklyn headquarters, according to an estimate provided by a person with direct knowledge of the spending. The campaign denied that figure. The campaign boasted last June, when Mrs. Clinton held her kickoff event on Roosevelt Island in New York, that it had at least one paid staff member in all 50 states. But the effort did not last, and the staff members were soon let go or reassigned….For all its institutional advantages, the Clinton campaign lags behind the Sanders operation in deploying paid staff members: For example, Mr. Sanders has campaign workers installed in all 11 of the states that vote on Super Tuesday. Mrs. Clinton does not.

Even Bill Clinton is questioning the strategic wisdom of the Clinton campaign:

Bill Clinton is getting nervous.

With polls showing Bernie Sanders ahead in New Hampshire and barely behind, if at all, in Iowa, the former president is urging his wife to start looking toward the delegate-rich March primaries — a shift for an organizing strategy that’s been laser-focused on the early states.

Bill Clinton, according to a source with firsthand knowledge of the situation, has been phoning campaign manager Robby Mook almost daily to express concerns about the campaign’s organization in the March voting states, which includes delegate bonanzas in Florida, Illinois, Ohio and Texas.

Many Clinton allies share the president’s desire for more organization on the ground; they see enthusiasm that’s ready to be channeled, but no channel yet in place. “Iowa matters a ton, but it seems to be the campaign’s only focus,” said one person close to the campaign’s operations in a March state — one of nearly a dozen Clinton allies with whom POLITICO spoke for this article. “It’s going to be a long primary, and the campaign seems less prepared for it than they were in 2008.”

9. We Are All Socialists Now

From :

Little noticed in this week’s Des Moines Register-Bloomberg Politics Iowa poll was this finding: a remarkable 43 percent of likely Democratic caucus participants describe themselves as socialists, including 58 percent of Sanders’s supporters and about a third of Clinton’s.

And it’s not just Iowa:

Senator Bernie Sanders’s speech on Thursday explaining his democratic socialist ideology carried little risk among supporters and other Democrats: A solid majority of them have a positive impression of socialism, according to aNew York Times/CBS News poll released this month.

Fifty-six percent of those Democratic primary voters questioned said they felt positive about socialism as a governing philosophy, versus 29 percent who took a negative view.

10. The Gender Gap

Another pundit shibboleth is that Sanders is not popular among women. There is a gender gap in this primary, in fact, but it’s not what the pundits are saying. According to the latest USA Today poll:

There is a gender gap as well — and not the one that favors Clinton among baby boomer women. Men under 35 support Sanders by 4 percentage points. Women back him by almost 20 points. The possibility of breaking new ground by electing the first female president apparently carries less persuasive power among younger women than their mothers’ generation.

Stone is ready to support Clinton, though she prefers Sanders. “He’s actually talking about breaking up the big banks and helping income inequality,” she says, “and given that I’m currently unemployed, income inequality is pretty important.”

A fact that apparently has caught the Clinton campaign completely off-guard:

Mrs. Clinton and her team say they always anticipated the race would tighten, with campaign manager Robby Mook telling colleagues last spring that Mr. Sanders would be tough competition. Yet they were not prepared for Mr. Sanders to become so popular with young people and independents, especially women, whom Mrs. Clinton views as a key part of her base.

11. Chelsea Mourning

Chelsea Clinton, who lives in a Gramercy Park apartment that she and her husband bought three years ago for $10.5 million, says:

I was curious if I could care about (money) on some fundamental level, and I couldn’t.

Reminds me of that old joke: One fish asks another, “How’s the water?” The other replies, “What the hell is water?”

12. The Immense and Shitty Hassle of Everyday Life Under Capitalism…

Arin Dube launched an interesting discussion on his Facebook page the other day. Riffing off of a bunch of Paul Krugman’s posts, which are fairly critical of Sanders’s health-care plans, Arin wondered whether Sanders’s focus on single-payer, after all the drama and struggle over Obamacare and its achievements in terms of extended coverage, really makes political sense. There are excellent arguments on all sides, and Arin’s voice is always one that I listen to. But I posted this comment on his page because I have this nagging feeling that a lot of the discussion around health care and insurance in the media is missing a critical reality. I’m posting it less as a definitive statement and more as an opening to see if my own intuitions and experiences track with those of others. I recognize that I really could be an outlier here, so feel free to tell me that I am. I just find it hard to believe that my experience of this system is so completely sui generis. Anyway, here’s an edited version of what I said:

Can I speak to this less from the policy or political perspective or more from the individual perspective, as a way of getting to the political perspective?

My family has insurance: I get mine from CUNY and my wife and daughter get theirs from my wife’s employer. From what I can gather, we have decent insurance. Yet when I think about the mountains of time I have to spend dealing with health care and insurance—the submission of forms, the resubmission of forms, haggling with the insurance companies to make sure things that should be covered are covered (or simply to make sure that forms are being processed at all), getting the doctor to revise forms b/c the diagnostic or procedure codes may not be correct or may have changed (which they do with alarming frequency, it seems)—and the consistent surprises I experience about how much we still have to pay—after the deductibles, the premiums, the co-pays, the out-of-networks are accounted for—before we even get reimbursed, I can’t quite believe the statements that are out there about how there’s just not a constituency for further reform.

Again, we have pretty good insurance. We are pretty healthy and don’t have out-of-the-ordinary needs. We are comparatively well off and highly educated. Yet there’s an inordinate hassle of time, and in the end a lot of costs we have to absorb ourselves (and a tremendous amount of confusion, despite my PhD, about how those costs get calculated and distributed), which I find maddening (and expensive!)

Am I just that sui generis? Or is it that the academic and media discourse is so focused on a certain kind of aggregate data that it ignores that there are huge costs that are being shouldered by individuals—and that if there were political leadership that could really speak to those costs, there might be more of a constituency than we realize?

What I take Sanders to be doing is making these individual costs a public or political problem; what I see mostly happening in the discussion is a shuffling off of those costs onto the individual so that they simply disappear from the political calculus. It’s a classic issue of politics: one side (a very small side, it seems) wants to make what is personal and individual into something public and political, while another side— including, it seems, a lot of reformers—tends to escort those personal and individual experiences off into the shadows.

What I’m saying here doesn’t confront, I recognize, the reality of the institutional intransigence of those who are opposed to reform. That’s a separate issue.

But when I hear that Obamacare has solved this problem for 90% of the population, and I think that my family is up there in the relatively well off sector of that population yet experiences significant costs and burdens that we find very hard to shoulder and understand—well, I just wonder if we’re really seeing this reality whole.

I was building here on an old theme of mine: the immense and shitty hassle of everyday life that is life in contemporary capitalism. I wrote about that in Jacobin a few years ago.

In the neoliberal utopia, all of us are forced to spend an inordinate amount of time keeping track of each and every facet of our economic lives….We saw a version of it during the debate on Obama’s healthcare plan. I distinctly remember, though now I can’t find it, one of those healthcare whiz kids — maybe it was Ezra Klein — tittering on about the nifty economics and cool visuals of Obama’s plan: how you could go to the web, check out the exchange, compare this little interstice of one plan with that little interstice of another, and how great it all was because it was just so fucking complicated. I thought to myself: you’re either very young or an academic. And since I’m an academic, and could only experience vertigo upon looking at all those blasted graphs and charts, I decided whoever it was, was very young. Only someone in their twenties — whipsmart enough to master an inordinately complicated law without having to make real use of it — could look up at that Everest of words and numbers and say: Yes! There’s freedom!

13. Clarence Thomas and Free Speech

This has nothing to do with the election, but what the hell.

I did manage, when I wasn’t tearing my hair out or having an aneurism over the campaign commentary, to read a lot of Clarence Thomas and secondary work on commercial speech. And it struck me in reading all this material that Citizens United and campaign finance law may be a massive sideshow to the real drama around money/speech that’s occurring in conservative jurisprudential circles. Conservatives aim, it seems, to use the First Amendment to strike down entire economic regulatory regimes at the state and federal levels. On the grounds that so much of commercial life is a mode of speech, which should be protected like other modes of speech. In one instance they struck down a licensing law in DC that required tour guides to be registered with the city: violation of free speech. Thomas is at the center of this, and it’s really unclear how far the conservatives on the Court will be willing to go. It raises some fascinating questions because the connection between money and speech—as I’m discovering in this excellent dissertation I’ve been reading—is an old and surprisingly complicated one in political theory, in which Aristotle and Locke play critical roles. (Locke’s pamphlet against the devaluation of the pound may have been, according to this author, the single most influential writing he did up until the 19th century.) Anyway, lots going on in this arena, which we should all be paying more attention to.

14. Politics Without Bannisters

There’s a lot of fretting—both well meaning and cynical—out there about whether Sanders can win.

Here’s the deal, people. For the last decade and a half, we’ve been treated to lecture after lecture from on high about how if you want things to change, you have to build from below. Well, that process has been going on for some time.

Unlike purists of the left and purists of the center (who are the most insufferable purists of all, precisely because they think they’re not), I look at the various fits and starts of the last 15 years—from Seattle to the Nader campaign to the Iraq war protests to the Dean campaign to the Obama campaign to Occupy to the various student debt campaigns to Black Lives Matter—as part of a continuum, where men and women, young and old, slowly re-learn the art of politics. Whose first rule is: if you want x, shoot for 1000x, and whose second rule is: it’s not whether you fail (you probably will), but how you fail, whether you and your comrades are still there afterward to pick up the pieces and learn from your mistakes.

Though I’ve not been involved in all these efforts, I know from the ones that I have been involved in that people are learning these rules.

But at some point, you have to put that knowledge to the test. Now the Sanders campaign is putting it to the test. Is it too soon? Maybe, probably, I have no idea. None of us does.

But you can’t possibly think we got anything decent in this country without men and women before us taking these—and far greater—risks, taking these—and far greater—gambles.

Sometimes I think Americans fear failure in politics not for the obvious and well grounded reasons but because they are, well, Americans, that is, men and women who live in a capitalist civilization where success is a religious duty and failure a sin, where Thou Shalt Succeed is the First Commandment, and Thou Shalt Not Fail the Tenth.

Is it not the right time for the Sanders campaign? The Republicans control the Congress, Sanders might lose to Trump or whomever, we don’t have the organizational forces in place yet? Well, re the first two concerns, when will that not be the case?

As for the third, well, that’s a very real concern to me. But we won’t know in the abstract or on paper; we have to see it in action to know.

Right now, the voters of Iowa and New Hampshire are telling the pundits and fetters: we are reality, deny us at your own peril. (I’m fantasizing a campaign where Sanders racks up more and more victories, and the pundits get more and more hysterical: he can’t win, he can’t win!) Maybe the putative realists—for whom reality seems to be more of a fetish or magical incantation—ought to listen to them.

15. Fame

Oh, and did I mention that I got retweeted by Killer Mike?

16. Speaking of fame (in memory of David Bowie)…

First They Came For…

First they came for the Revolution

and I did not speak out

because I was not a Revolution.

Then they came for the Parliamentary Socialism

and I did not speak out

because I was not a Parliamentary Socialism.

Then they came for the Third Party

and I did not speak out

because I was not a Third Party.

Then they came for the Democratic Wing of the Democratic Party

and I did not speak out

because I was not a Democratic Wing of the Democratic Party.

Then they came for the Green Lantern

and I did not speak out

because I was not a Green Lantern.

Then they came for me

but that was cool

because I’m a Democrat.

January 20, 2016

Chickens Come Home to Roost, Palin-Style

Sarah Palin’s son Track, who’s a veteran, has been arrested for allegedly punching his girlfriend. The former vice presidential candidate had this to say:

“My son, like so many others, they come back a bit different, they come back hardened,” she said. “They come back wondering if there is that respect for what it is that their fellow soldiers and airman and every other member of the military so sacrificially have given to this country,” she added. “And that starts from the top.”

“That comes from our own president,” she elaborated, “where they have to look at him and wonder, ‘Do you know what we go through? Do you know what we’re trying to do to secure America?'”

“So when my own son is going through what he goes through coming back, I can certainly relate with other families who kind of feel these ramifications of some PTSD and some of the woundedness that our soldiers do return with,” she continued before pivoting back to her Trump endorsement. “And it makes me realize, more than ever, it is now or never, for the sake of America’s finest, that we have that commander-in-chief who will respect them and honor them.”

The interwebs are having a field day. I think that’s a mistake.

I’ve held for a long time that one of the keys to understanding the right is that it borrows from the left. Sometimes strategically, sometimes unknowingly.

More recently, in my work on Clarence Thomas, I’ve noticed how skilfully he navigates the traditional waters of the left, churning up the chum leftists used to wade in, but without proposing anything that would clean up the water.

Here we see the same thing with Palin. The left used to argue that military violence abroad would find its way home: in racist vigilantism, heavy policing, and domestic and substance abuse. Since the 1980s, though, the left has grown nervous about making those connections. Enter the right. Rather than focusing on the violence, however, conservatives focus on whether Obama respects the uniform.

It’s Chickens Come Home to Roost, Palin-style.

January 14, 2016

Ellen Meiksins Wood, 1942-2016

I came to Ellen Meiksins Wood’s work late in life. I had known about her for years; she was a good friend of my friend Karen Orren, the UCLA political scientist, who was constantly urging me to read Wood’s work. But I only finally did that two years ago, at the suggestion of, I think it was, Paul Heideman. I read her The Origins of Capitalism. It was one of those Aha! moments. Wood was an extraordinarily rigorous and imaginative thinker, someone who breathed life into Marxist political theory and made it speak—not to just to me but to many others—at multiple levels: historical, theoretical, political. She ranged fearlessly across the canon, from the ancient Greeks to contemporary social theory, undaunted by specialist claims or turf-conscious fussiness. She insisted that we look to all sorts of social and economic contexts, thereby broadening our sense of what a context is. She actually had a theory of capitalism and what distinguished it from other social forms: that it was not merely commercial exchange, that it did not evolve out of a natural penchant for barter and trade, that it was not a creation of urban markets. Hers was a political theory of capitalism: capitalism was created through acts of force and was maintained as a mode of force (albeit, a mode of force that was exercised primarily through the economy). She was also a remarkably clear writer: unpretentious, jargon-free, straightforward. Just last week, I had started reading Citizens to Lords, and I’d been slowly accumulating a list of questions that I hoped to ask her one day on the off-chance that we might meet in person. Now she’s gone. The work continues.

January 9, 2016

On Islamist Terror and the Left

Glenn Greenwald speaks to and rebuts a rhetorical move that’s become common across the political spectrum: when it’s pointed out that US and European foreign policy makes some contribution toward radicalizing Muslim populations, including the turn to terrorism, the response is that anyone who makes such a claim is: a) denying the agency and autonomy of terrorists; b) overlooking the role of religion as an independent variable, which some want to see as completely unrelated to any other variable. You see this response increasingly among certain parts of the left, and Glenn shows why it’s wrong.

I would add two points to Glenn’s analysis.

First, with regard to the agency/autonomy claim, it surprises me that leftists would repeat an argument that conservatives pioneered in their assault on liberal and left approaches to crime in the 1970s. Whenever the left tried to see crime as a symptom in part of social and material conditions, the right accused the left of engaging in excuse-making and a denial of individual responsibility. It was a simplistic, though lethally effective, political move, which has now, in the context of the debate over Islamist terrorism, migrated across the political spectrum.

Come to think of it, that move today re agency and autonomy also reprises what a lot of liberals did in their attacks on the French and Russian Revolutions in the 1970s and 1980s. Against anyone who tried to see the Terror or Bolshevik violence as in some measure a response to material realities (the persistence of the old regime, the threat of counterrevolution and foreign invasion, etc.), it was claimed that such a view eclipsed the role of revolutionary agency and ideology. Yet in making that argument, liberals threatened to separate entirely revolutionary agency and ideology from the realities of political and economic life, as I argued in this piece I did for the Boston Review on Arno Mayer’s study of terror in the French and Russian revolutions.

The two analogies here are admittedly imperfect because some leftists today do want to see religious fundamentalism and terrorism as a response to real conditions, only theirs is a particular account of what those conditions are: not the power politics of US or European imperialism but instead the secular changes of capitalist modernity, which threaten established identities and familiar social ties, creating an enervating anxiety and anomie. Here these leftists reprise an old psycho-social argument of 19th and 20th century social thought, which I analyzed in my first book on fear, and which, ironically, was historically used by liberals against the left (just read Arthur Schlesinger or Talcott Parsons). Which brings me to my second point.

Second, with regard to the religion argument, I can’t help but feel that some of the left are using the Islam/terrorism nexus as a way of conducting their own campaign, rooted in the domestic politics of the West, against a) what they see as a softening on the religion and identity question among the left; and b) what they see as certain moralistic/puritanical, quasi-religious, tendencies on the left. It seems like leftists should just have that debate—about the role of religion in politics, about the sources of religious belief and identity, about the proper role of morality, etc.—out in the open, and not try to conscript areas and peoples of the world that it knows little about in order to conduct a thinly veiled battle against their opponents.

January 8, 2016

When White Men Complain…

Clarence Thomas:

Most significantly, there is the backlash against affirmative action by “angry white men.” I do not question a person’s belief that affirmative action is unjust because it judges people based on their sex or the color of their skin. But something far more insidious is afoot. For some white men, preoccupation with oppression has become the defining feature of their existence. They have fallen prey to the very aspects of the modern ideology of victimology that they deplore.

—”Victims and Heroes in the ‘Benevolent State,'” Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy 19 (Spring 1996)

January 7, 2016

Clarence Thomas on the One-Party State that is our Two-Party System

From Clarence Thomas’s dissent in McConnell v. Federal Election Commission (2003):

The joint opinion also places a substantial amount of weight on the fact that “in 1996 and 2000, more than half of the top 50 soft-money donors gave substantial sums to both major national parties,” and suggests that this fact “leav[es] room for no other conclusion but that these donors were seeking influence, or avoiding retaliation, rather than promoting any particular ideology.”Ante, at 38 (emphasis in original). But that is not necessarily the case. The two major parties are not perfect ideological opposites, and supporters or opponents of certain policies or ideas might find substantial overlap between the two parties. If donors feel that both major parties are in general agreement over an issue of importance to them, it is unremarkable that such donors show support for both parties. This commonsense explanation surely belies the joint opinion’s too-hasty conclusion drawn from a relatively innocent fact.

Lefty critics of the American two-party system have complained for years that there is too much ideological alignment between the two parties, particularly on questions of economics and corporate power, as evidenced by the fact that many wealthy donors are only too happy to give to both parties. Clarence Thomas doesn’t disagree.

January 6, 2016

Goodbye, Lenin

Sanford Ungar, an author and former president of Goucher College (might he also be the historian whose articles on the FBI or the CIA I read for my dissertation many moons ago?), has an oped in the Washington Post, criticizing the recent efforts to remove Wilson’s name from Princeton, take Jackson off the $20 bill, and so on. There isn’t anything new in the piece (Wilson was complicated, Jackson did some good things, etc.) But this last paragraph caught my eye:

What is at stake, in the end, is an understanding of our own history. We certainly must confront the reality that many of our greatest public figures did not always live up to American ideals. But wiping out the names, Soviet-style, of key actors who shaped the society, and world, that we live in today, will not help that process.

That “Soviet-style” reference intrigues me.

After 1991, when people in the former Soviet Union began toppling statues of Lenin, no liberal-minded person—at least none that I can recall—raised any alarm bells about “Soviet-style” erasure. Indeed, removing these signs and symbols of the past was considered the very essence of anti-Soviet-style politics. It was an act of emancipation.

But when we remove the name of Wilson or the face of Jackson, liberation becomes erasure, anti-Soviet-style politics becomes Soviet-style politics.

I get the Lenin/Stalin-was-worse-than-Wilson position. But surely that can’t explain the whole of it. If anything, one would think that in the wake of total domination, we should be even more solicitous of the past. To understand how such tyrannical regimes work, we need to unearth all their secrets, which can be hidden in the most unexpected places. Before we remove anything, we should make sure we’ve thoroughly excavated its every last nook and cranny. Conversely, it’s not clear to me why removing the symbol of some great wrong from the past is made less liberatory by the fact that that wrong was alloyed with some good, even some great good.

So we’re left with the question: If removing the signs and symbols of the past is supposed to threaten our understanding and appreciation of that past—and that is Ungar’s point, after all— how does erasure become freedom in the one instance and tyranny in the other?

Corey Robin's Blog

- Corey Robin's profile

- 163 followers