Eva Hnizdo's Blog, page 6

August 28, 2021

When you read my book after 28th September, if you like it could you review it? Please?

It is exactly one month before my novel’ official publishing day. 28th September. The book is already available in paperback, the e-book doesn’t come for another month. Some of my friends and family already have my paperbacks from the author’s copies I received.

I am nervous. Suddenly I have a crazy idea that it might be a good book. Will other people think so? This will be a long wait, and I am impatient.

I am also thinking about that saying.

If you don’t like it, tell me. If you like it, tell everybody else.

So please, if you like it, could you review my book on Amazon and maybe also Goodreads?

If you don’t like it, I’d like to know, too, and why, but let’s keep it to ourselves.

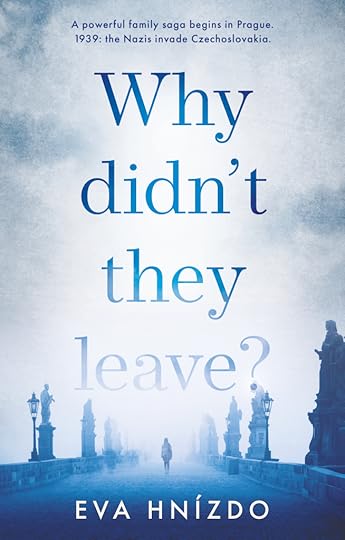

this is what I look look like and what the book looks like

this is what I look look like and what the book looks like

August 26, 2021

My book" Why Didn't They Leave?" is now available

The publishing is not till 28th September.

I was asked to come on the Four Thoughts program of BBC Radio 4, which was very exciting. It will be broadcast in the end of September.

I've been giving my author's copies out, and now I wonder if people will like it. I hope so!

August 25, 2021

A simple summary of the historical background of my novel.

1918-1945

Czechoslovakia became independent after the breakup of the Austro-Hungarian empire in 1918 when the WW1 finished.

It used to be an independent kingdom of Bohemia but despite still keeping the name, it was ruled by the Austrians since 1620.

Czechoslovakia after 1918 was a prosperous democratic republic.

Prague had a long history of Jewish inhabitants, and the Old New Synagogue in Prague , built 1270 is the oldest active synagogue in Europe. Prague was a cosmopolitan city with the often-bilingual Czech, Jewish and German intellectuals living together. There was a large German minority, in the country since 11th century. The Jewish population was very assimilated, and to a large extent secular. Comparing to many other Central European countries, anti-Semitism was relatively rare.

My novel covers 1938-2006 in Czechoslovakia, UK, USA and partly Grenada and IsraelIn September 1938, in Munich agreement Britain, France, Italy and Germany changed the border by accepting Hitler’s demands to annex the Czechoslovak border regions with the majority of Ethnic Germans to Germany. This was an appeasement strategy meant to preserve “ A peace in our time”- quote from Neville Chamberlain, British prime minister. This was meant to be the last Hitler’s territorial demand .

Of course, the peace didn’t last long.

On 15th March 1939, Hitler invaded the rest of Czechoslovakia, and the Slovak part of the country split, forming independent and fascist Slovakia.

For the Jews, the situation became gradually worse, starting with discriminatory laws, later leading to deportations and killings.

1945-1948

After the war, there was a short time of return to democracy, and re-joining of Czech speaking part and Slovakia. The communist party was very successful in the post-war elections, still within the democratic parliamentarian democracy, but in 1948, there was a communist putsch supported by Stalin, and Czechoslovakia joined the Soviet bloc.

In 1952, 13 high-ranking Communist bureaucrats (10 of whom were Jews) were arrested and charged with being Titoists and Zionists. Many were executed.

1968

In the sixties, there was a gradual democratisation of the society, the censorship was relaxed, and in 1968, there was an attempt to change the system. They were still speaking about socialism, “Socialism with a human face”. Reforming communism didn’t work.

On 21st August 1968, Soviet and other armies from the Warsaw Pact invaded Czechoslovakia, followed by a return to totalitarian state oppression.

1989

The Velvet Revolution changed the country to a democracy again.

1993

The Federal Czechoslovakia split into Czech and Slovak republic.

2004

Both countries joined the European Union

August 14, 2021

Being antisocial in Marbella

I go on beach holiday by myself. When I used to go with friends, they were complaining that I don’t talk to them. Normally, I never shut up, but in this instant they were right. On the beach or by the pool, I read, swim, sometimes listen to audiobooks. No talking. I used to talk to friends at dinner, that was nice. But now I am travelling alone, I don’t mind. In the restaurants, I order the food, read, eat, pay and go.

In the evenings, I am usually writing on my laptop.

This time, because of my book launch, I also had phone calls and emails about my book. I had a very kind and generous offer from the International Women’s Writing Guild ( IWWG) of which I am a member, that they will include me as a featured reader on an Open Mic this autumn. They will ask me some questions and I will be able to read for about 18 minutes from my book. Very exciting.

Marbella is beautiful, but I only spent some time going to eat out in the evening.

6 weeks before the book launch is a busy time.

In the hotel, there was a nice English couple who kept talking to everybody, small talk, very friendly, but not my thing. The third day, their lounge chairs were next to mine. I smiled and continued reading. That didn’t stop the questions and chat. What worked was me exaggerating my already strong Czech accent and saying. “ My English not so good”. We exchanged friendly grins, and that was it.

Unfortunately, two days later, I was chatting to somebody from the BBC on my mobile, in English, in a Czech accent, of course, but in the way I normally speak. I am lucky, BBC Radio 4 will record a program about emigration with me. It is a series called For Thought. They will mention my book, too. That is of course amazing. I talk louder when I am excited.

I only noticed the chatty couple sitting behind me when I stopped the phone call.

Embarrassed, I didn’t know what to say. Then I went for the truth.

“ I am so sorry, I like my solitary holidays, so I sometimes pretend I only speak Czech. I was antisocial. Please forgive me.”

I smiled and went for a swim. Rude, I know.

Were they angry? Probably. They also probably talked to others. Nobody talked to me, not even at the airport. But the British are a tolerant lot. They were all still smiling at me when I said “ Hello” and only replied “ Hello” back. No weather talk, no questions, just smiles. I should have been nicer, maybe even telling them about my book. But I didn’t talk to anybody…

I had a nice holiday and did a lot of work, too.

Did they judge me? Will you judge me when you read this? Maybe. I hope not. I only get like this on a beach holiday…and before a book launch.

August 5, 2021

Excited

Why didn't they leave?

The publishing date is 28th September. Paperback and an e-book.

I have been asked to do some interviews, and I will appear on a BBC Radio 4 program https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b010...

It will be about emigration, but I am allowed to mention my book. It will be recorded soon, but probably won't be broadcasted till November. There will be a podcast, too. Fortunately it is not live so if I talk nonsense, they can re-record it! But I will try NOT to talk nonsense.

July 27, 2021

What has my book Why didn’t they leave? has in common with Good King Wenceslas carol?

The date my book will be published by Book Guild publishers is 28th September, it is a holiday in Czechia, the Czech Statehood Day.

Stained Glass window in St. Vitus Cathedral, Prague, depicting Wenceslaus I or Vaclav the Good, Duke of Bohemia

Stained Glass window in St. Vitus Cathedral, Prague, depicting Wenceslaus I or Vaclav the Good, Duke of Bohemiacopyright ©jorisvo/123RF.COM

It is the anniversary of the assassination of king Vaclav- the Good king Wenceslas from the English Christmas carol. He was sainted and is the patron of Czech lands.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wenceslaus_I,_Duke_of_Bohemia

I don’t quite understand why the anniversary of his assassination should be the Statehood Day, nor how he got to the English Christmas carol.

However, it reminds me of the strong Czech patriotism of my Jewish ancestors. They loved the country, the first president Thomas Garigue Masaryk, they felt Czech before they felt Jewish. It didn’t help them in the war, but they would probably all agree with me saying I am a Jewish Czech, not a Czech Jew, do you understand the difference?

July 24, 2021

Thinking about immigration

My publisher is starting the media marketing campaign. It is only in the UK, but the book will soon be available in other countries too.

I had my picture taken for the publisher, and when I talked to the men in the photo shop, and when I told them what the book is about, we realised we were all refugees.

One from Eritrea, one from, Somalia, one from Bosnia. I came from Czechoslovakia. Some of us could go back, some can’t.

I am of course a refugee, too, although I can now go back. I won’t, England is my home now.

It made me realise again how important those refugees’ contributions to the society are.

So many people working in so many professions. I worked in the British NHS- health service for 28 years, In London, we foreigners are everywhere.

I like it, but I am biased.

This a copy of the press release:

PRESS RELEASE

WWW.BOOKGUILD.CO.UK

Why Didn’t They

Leave?

Inspired by her own family history, Eva Hnizdo deals with themes of identity, racism and belonging as an immigrant in Britain.

You can’t ask for asylum in another country just because your mother drives you nuts, so when 19-year old Zuzana flees from communist Czechoslovakia to England in 1972, she says she just wants freedom.

Her relationship with her mother, Magda – a Holocaust survivor who lost most of her family in the concentration camps – is toxic and Zuzana finds happiness in London with a loving husband and beautiful son.

But when her mother dies, Zuzana is crushed by guilt and feels an overwhelming urge to discover more about her family’s tragic history. So, she embarks on a life-changing journey, discovers some incredible

stories and tries to answer the question which haunts her: Why didn’t they leave?

Eva Hnizdo is a Jewish Czech, born in Prague in 1953. She is the granddaughter of a man who lost his life by deciding not to emigrate in 1938, and a daughter of parents who, after surviving the Holocaust,

spent most of their adult lives under an oppressive communist regime. Eva studied medicine at Charles University in Prague and became a doctor. She escaped to the West in 1986 and obtained political asylum in the UK in 1987 with her husband and two sons. She worked as a full time GP partner at the same surgery in Watford for twenty-three years. Now retired, she spends her time writing.

Eva says, “I know from my family history that people can find themselves in a situation where their home is no longer safe. Suddenly, they don’t belong.

Their identity somehow changes. However, identity depends also on how other people see us. I emigrated from communist Czechoslovakia in 1986. I was lucky, the Cold War was still on, getting political asylum was easy for me, I was also European, white, a doctor. I felt welcome in the UK.

There are millions of people running away from famine, wars, discrimination. Most of

them are not white, they are poor, sometimes not educated. They need us. The novel is about people who did leave their homeland, their reason for emigration, and the emotional price they paid as a result, but

also about the many people who chose to stay and often paid for that choice with their lives.”

RELEASE DATE: 28/09/2021

ISBN: 9781913913366 Price: £9.99

SAGAS

for author interviews, review or competition copies, articles, photos or extracts:

PHILIPPA ILIFFE, ASSISTANT MARKETING MANAGER

Tel: 0116 279 2299 Email: P_ILIFFE@BOOKGUILD.CO.UK

the book guild ltd, 9 priory business park, kibworth, leicester le8 0rx

July 19, 2021

Now the book is slowly possible to pre-order, here is a taster – the first chapter. Hopefully you will want to read the rest.

This is the worst day ever, Magda Stein sobbed as she walked home. She walked past the renaissance palaces of Mala Strana, and across the bridge over the River Vltava. Normally she would look at the beautiful view of the Prague castle from the bridge. Today, she didn’t notice where she was going. It started raining, and the raindrops were mixing with Magda’s tears. People were looking at her, but 12-year-old girls cry easily, those strangers on the street probably thought she had an argument with her friends or lost something. This was much worse. Today, Magda had been told she couldn’t go to school anymore.

The teacher asked all Jewish children to go to the school gym after lessons. The headmaster was waiting for them. He was pacing up and down on the small, elevated platform that was sometimes used for children’s concerts and theatre performances, his shoes made a squeaky sound. He was pale and talked very quietly.

“We have been told that we are no longer allowed to have Jewish pupils. I am very sorry.”

His eyes were looking on his feet. Magda did that when she was lying. What will we do? she thought.

Magda loved going to school. She always had good marks, and she liked to hold her hand up first when the teachers asked questions. Sometimes, she didn’t know the answer when she put the hand up, but by the time the teacher called her up, she was ready to say something, and she was often right. It didn’t always work. The week before, she didn’t know the answer.

“So, what is it, Magda?” the teacher asked.

“Oh, I forgot! Sorry.”

Everybody laughed at her. Usually, Magda was part of the popular group of girls who laughed at the ones they singled out as weird. Girls like bespectacled Ela, who wore ugly shabby clothes and read books in the interval instead of playing or talking with the other girls. Sometimes Ela was so engrossed in her book that she didn’t notice the school bell marking the beginning of the next lesson.

“Four-eyed Ela, wake up, the teacher’s coming!”

Ela dropped the book, rushing to her desk. Or the fat shy Jana, always eating something her mother baked in their bakery shop. The girls called her Stuffed Face. But when the girls laughed at Magda last week, she didn’t like it.

Now, she couldn’t go to school anymore. My brother Oskar doesn’t like school; he’ll be happy. The only thing he likes is football. Magda thought.

In the physical exercise lessons, Magda couldn’t do the things other children could, jump over the vault, climb the pole or the rope. She always got the giggles and got stuck in the middle of the climbing rope.

“Come on, Stein, climb up or down.”

The teacher hated it, but she had to help Magda to climb down. PE was the only subject where Magda never got the top mark. Who cares? Magda’s brother Oskar was in his school football team, and he ran, too. He kept teasing Magda that she was fat and clumsy. Well, he is stupid. I am far cleverer than he is. Even Daddy says that. It’s better to be clever and clumsy than stupid and good at moving, like a monkey. The image of her brother turning into a monkey made Magda stop crying.

Magda’s father Bruno told her she was his little princess. When he was at home, Magda often sat on his lap, and he told her stories. Daddy loves me. Magda was not so sure about her mother. Of course, Mummy loves me, too, but she prefers Oskar. Mummy can be nasty to me sometimes. Last week, Magda ate half of the chocolate cake their cook Anna was preparing for dinner. There was plenty of it left for everybody, but Anna got angry. Magda’s mother Franzi got very cross, too — she sent Magda to her room without any supper. The punishment didn’t last long. Magda had a secret weapon whenever her mummy punished her. She cried, loudly, sometimes for hours, like an actress. Eventually, her father couldn’t bear it and came to her rescue. When Magda couldn’t cry any more, she started thinking about something very sad, like cute little puppies dying. Then she could cry again. It worked. Her daddy didn’t want his little Princess to be unhappy.

When she cried like that after the cake punishment, Bruno took his daughter back to the dining room after exactly 10 minutes, she checked on her nice Longines Swiss watch that she got for her birthday. She was still allowed to eat her dinner. Not the cake, her mother didn’t allow it. But Magda had enough of that cake anyway.

The cook Anna didn’t seem to like Magda; she kept chasing her from the kitchen. It didn’t occur to Magda that it might have something to do with her always eating sultanas and looking into the pots to find out what was Anna cooking. Once, Magda dropped the pot of soup she was tasting, and Anna had to make the soup again from scratch. Fortunately, Magda didn’t get scalded, but the soup went everywhere, on the hob and on the floor.

Anna used to be a cook for one of Franzi’s Czech friends, who was moving from Prague to Brno. “She’s a wonderful cook, but moody, I hope you can cope with that, Franzi,” the friend said.

The friend was right, Anna had a temper. Almost every month, she gave Magda’s parents her notice about something silly, only for Bruno and Franzi to beg her to stay. Yet, she always stayed and soon became almost part of the family.

Magda remembered when the Nazis arrived in Prague. It was 15 March 1939. They were standing on the pavement, Franzi was holding Magda’s and Oskar’s hands, Bruno was standing behind them. It was very cold for March, and sleet was blowing in their faces. Magda was watching those cars and tanks, driving on the other side of the road. Their steering wheels were on the left, not on the right like her daddy’s car. The cars used to drive on the left, but the Nazis changed that in one day. They just kept driving on the right when they crossed the border.

The pavements in Prague were full of people, watching the invasion. That was the first time Magda saw her daddy cry, although he told her that it was the sleet hurting his eyes when she asked him. He was not the only one, many of the adults on the pavement seemed to cry. Now the Nazis were in power. What used to be Czechoslovakia was now called Böhmen und Mähren. The country was much smaller now. After the Nazis invaded Poland, too, the war started.

Magda used not to care if she was Jewish. Sometimes she felt it was great to be both Czech and Jewish. In December, Hanukkah brought the candles, the dreidel game – the dice with Hebrew letters. She liked the little gifts of chocolate coins and other sweets that she and Oskar got every one of the eight days of Hanukkah, and the festive meals. Sometimes, Franzi let her light the candles. But unlike many other Jewish families, for Magda’s family, the celebrations did not end on the eights day. The family celebrated Christmas, too, in the house of her uncle Otto, who was married to a non-Jew.

Otto and his wife Marie didn’t have any children, but they always had a Christmas tree and Aunt Marie baked ten sorts of Christmas cookies. She had a cook, like Magda’s family, but she said that she preferred cooking the Christmas meal herself. All the family went there for dinner every Christmas Eve, and they always had fried carp with potato salad. Magda didn’t like carp, you had to watch for bones.

“Don’t talk, Magda, you will get a fish bone stuck in your throat and it would have to be cut out!” she remembered her father saying.

Bruno probably just wanted to scare her, but why not have meat instead of fish, and be able to talk at dinner? The Czech Christmas cookies were yummy, especially the little moon shaped vanilla rolls, made with ground almonds. Aunt Marie and Uncle Otto always left lots of presents for the children – Magda and her brother Oskar, cousins Irma and Gerd – under the Christmas tree. Cousin Hana wasn’t a child anymore, so she didn’t get any toys, but they always gave her books. The other adults never got any presents. Aunt Marie said the presents were from Baby Jesus, but Magda knew very well that Uncle Otto was buying them. Aunt Marie was a Roman Catholic like the Stein’s cook Anna. They both wore a cross on their neck. But otherwise they were very different. Aunt Marie was beautiful, whereas the cook Anna was fat and ugly, with a wart on her big nose.

“Anna’s nose is more Jewish than mine!” joked Bruno.

The religion classes in school were once a week, always the last lessons in the day, so that Catholic, Protestant and Jewish children could all go to a different class. Magda used to go to the Jewish religion class. The rabbi was old and couldn’t manage the children. There was such noise! The children talked, threw the wet sponge for washing the blackboard at each other and didn’t listen to the lessons. Magda only managed to learn some Hebrew letters. The letters were also used as numbers, strange.

“You sounded like a class of monkeys, not children.” Franzi once said when she was picking Magda up.

Later Magda went to the Protestant classes. The whole family was baptised shortly before.

“It might help us with the Nazis”, said Bruno.

The Protestant pastor Mr. Homola was nice. The way he told those biblical stories was a bit like theatre, he changed his voice, made faces. He also made Oskar, Magda, and the other Jewish children feel special. When they joined the class, he said: “We must all respect and be nice to these children, they come from an ancient tribe that founded our religion. They are our brothers and sisters, and they are living through hard times.”

It was nice, but it also made Magda giggle. Tribe? Like the American Red Indians from the books Oskar reads? I am not Jewish anymore; I am a Czech Protestant.

But the Nazis didn’t believe that. And now I can’t go to school, I will never see Pastor Homola again.

When Magda got home, Anna opened the door for her.

“Oh Anna, where is Mummy? Those stupid Nazis decided that Jewish children can’t go to school.”

Magda cried, and this time it was real. Anna embraced her, which was weird, but it was nice to be pulled to Anna’s large breasts, warm and soft, like lying on a pillow. Then she started baking a chocolate cake. That cheered Magda up and she stopped crying.

“Big chocolate cake, really?”

“Yes Magda, and it will be all just for you,” Anna said. “I will make something else for your brother.”

“Oskar hates school, he’ll be pleased!”

But she was wrong, he wasn’t. He tried to hide it, but Magda was pretty sure he was crying, too.

July 16, 2021

Only slightly more than 2 months till the book comes out!

I had to do the proofreading on my typeset book. One of my American friends, a writer, read the book for me, too, she said “ I want to read it anyway so might as well help with the proofreading. ” Very kind.

That is where I realised that grammatically, there are more differences between British and American English than I thought! Fascinating. She also told me about em and en dashes- never heard of them, I just use hyphen -.

I should apparently also never use ;;;;. But again, in Britain they do. I am getting published by a British publisher, so I am writing in British English ( with a Czech accent).

I have a zoom meeting with the marketing department of my publisher next week. I looked, and it is already on amazon UK:

It is exciting, but also scary. What if nobody reads it? Or what if they do read it but they think it’s terrible !?

Some people might say : How dare she write in English, when it is her 5th language? ( It is, but now after Czech my best one, my German, French and Russian got worse, and my English got much better.

But you know what? I believe one should be daring. What’s the worst that can happen? The book sinks? If it does, I am writing another one.

And if you want to say, “ How dare she?” you have my permission to do that.

May 31, 2021

I am not happy about the UK attitude to arrivals from abroad.

Photo by Miguel u00c1. Padriu00f1u00e1n on Pexels.com

Photo by Miguel u00c1. Padriu00f1u00e1n on Pexels.comI read this article

Unfortunately, it reminded me of my relative, cousin of my grandfather, an esteemed Jewish musicology University professor from Prague who was refused entry to Britain twice in 1939. He was travelling with his family.

He returned to Czechoslovakia, and after correspondence, got authorisation for a settlement visa in the UK. They travelled back and were again refused by the border guard in Dover ” because they were already refused once”. By then, the Nazis invaded the Czech part of Czechoslovakia and Slovakia split.

The chance of that British border guard being the cause of their death was high.

They were lucky. They contacted Princeton University in the USA where the professor was well known as a Mozart specialist, and Princeton University sponsored their settlement in the USA,

The son, then very young became a famous musicology professor, too. The whole family are accomplished educated people, a definite asset to the country they moved to.

How many such people is Britain loosing? How many lives are being endangered again? It is NOT just EU citizens, they are safe. The Home secretary Priti Patel wants to reform the asylum procedures, making it much harder to get political asylum .Being an ex-refugee myself and knowing history of my family and many others, I am sad.

The democratic Britain, place for people seeking freedom seem to have gone. And in my opinion, it will be the worse for it.