Neil Sharpson's Blog, page 24

August 14, 2020

Night of the Hunter (1955)

How quickly things change.

Not so long ago my awareness of Night of the Hunter boiled down, essentially, to this:

The preacher with the tattooed fingers. I knew it was an old movie from the fifties, I vaguely knew it was a serial killer drama and that it was considered to be a real good ‘un. But that was about where my knowledge of the film began and ended.

And now? Guys, I am a full on stan. With the insufferable zeal of the newly converted I will talk your ear off about this film. I will bore you to tears describing individual scenes. Every night I shake my fist at the heavens because I now know I live in the world where Charles Laughton only got to direct one film AND IT’S NOT RIGHT IT’S NOT SUPPOSED TO BE THIS WAY THIS WORLD IS A SICK JOKE.

Guys, this movie is an absolute work of art. It is beautiful to the point of transcendence. It is an aesthetic and stylistic triumph. It is quite good.

” Gasp!”

“Right?”

The story is one of the great Hard Luck tales in Hollywood’s long, glorious history of giving talented people the shaft. Legendary English actor Charles Laughton made his directorial debut with The Night of the Hunter, now regarded as one of the greatest first films ever made. Critics panned it, audiences stayed away in droves and Laughton tearfully shelved all plans to be a director and returned to the gentle bosom of the theatre where talent is always justly rewarded (pause for hollow, bitter laugh). Actually, I’m not entirely sure that first parts totally true. The few contemporaneous reviews from the time I’ve seen are by no means pans. In fact, they’re often quite effusive in their praise of the film and its director. They’re more just…confused. Like they don’t quite know what to make of this thing. And honestly, that’s fair. It certainly doesn’t fit into any tidy little box.

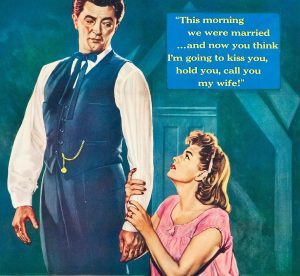

It’s a horror film, and an often extremely dark one, but from the perspective of a child and with the bulk of the film being carried by two child actors. It’s also a fairy tale, dreamlike and quite surreal in its tone. And lastly it’s an intensely Christian movie which nonetheless acts as an ascerbic and harsh critique of American Christianity. So it’s not exactly like you can do a “If you liked X, you’ll love The Night of the Hunter!“. So it’s understandable, if not not forgivable, that audiences slept on this when it first came out. Also, the poster is kind of terrible and makes it look like it’s a Lifetime drama about a man who desperately needs a dictionary.

“I don’t know what words mean!”

The movie opens with Rachel Cooper (Lillian Gish) reading a Bible story to her adopted children. She reads them Matthew 7:15, where Christ warns his followers of false prophets who use the trappings of faith to mask their evil.

Yes, yes, you don’t like it when I get political, I don’t like it when my faith is used as a prop by a fascist Orangutan. Things are tough all over.

We’re now introduced to our villain, Harry Powell (Robert Mitchum), driving along the Ohio river and having a friendly, one to one chat with God about all the women that he’s killed. He attends a striptease show where we watch him quietly seething in the audience with barely contained, murderous rage.

Sidebar: this movie made me realise that colour film was a terrible, terrible idea.

Before he can act on his impulses, he’s arrested for driving a stolen car and sentenced to thirty days in jail.

Meanwhile, in their garden, little John Harper (Billy Chapin) and his younger sister Pearl (Sally Jane Bruce) are playing when their father Ben suddenly arrives home in a mad panic and covered in blood. He hides a wad of bills in Pearl’s doll and swears the children to secrecy. Suddenly the police arrive and handcuff him on the ground while the children watch in horror.

Ben Harper is arrested for armed robbery and murder and sentenced to be hanged. He has the misfortune to share a cell with Harry Powell, who is able to piece together enough clues find Ben’s home town after he’s released.

In the town, Ben’s widow Willa is struggling to raise two children alone and has been largely ostracised by the community. Her only remaining friends are Walt and Icey Spoon, an older couple who’ve run the local general store ever since they escaped from a Grant Wood painting.

With a name like “Icey” I guess she should be glad she turned down that marriage proposal from Gustav Wiener.

Powell slithers into town and quickly suckers in all the townspeople. He explains his tattoos (“love” on one hand, “hate” on the other) as a teaching tool, demonstrating the eternal battle between good and evil by…pretending his two hands are fighting, and the locals just eat it up.

Look, it was before YouTube, entertainment was hard to come by in these small, rural towns.

John is getting serious stranger-danger from Harry but Willa is charmed by him and even Pearl seems willing to accept him as her new step-father. Harry and Willa are soon married and the townfolk are shocked when Harry tells them that Willa has dun runn oft, leaving him to mind her two children. We the audience, of course, know that she is in fact at the bottom of the lake, which Laughton reveals in one of the most eerily beautiful shots I have ever seen.

This was his first movie, people. His first.

Cinematographer Stanley Cortez would later say that of all the directors he worked with, Laughton was one of only two who truly understood light (the other being Orson Welles).

The scene where Powell tells the Spoons that Willa has dun runn oft is the best showpiece for why this is one of the all time great movie villain performances in movie history and the absolute tight rope walk that Mithcum is pulling off here. Mitchum finds the same sweet spot that Anthony Hopkins did with Silence of the Lambs. On one level he’s absolutely hilarious, hammy and even (dare I say it?) a little bit goofy. There’s something of the Devil in an old mediaeval morality play about Harry Powell, like he’s a hair’s breath away from turning to the audience, waggling his eyebrows and saying “I know you’re too smart to fall for this, but can you believe these rubes are buying it?”.

The ease with which any transparent charlatan with an effective sales patter and a few mangled Bible verses can win the complete trust of these people is entirely the point, of course. There’s a hilarious exchange between Harry and Icey:

: What could have possessed that girl?

: Satan.

: Ah.

And the way she says “Ah” is like “Oh, that prick”.

It’s great. But the wonderful thing is, this wonderfully funny, hammy performance does not undercut Powell’s menace at all because the movie makes clear that it’s all just an act. Every so often the veneer falls and we see the real Harry Powell.

Harry threatens the children at knifepoint until they reveal that the money is hidden in Pearl’s doll. They manage to trap him in the basement and steal a rowboat and sail down the river. Harry chases them and wades out into the water, waving his knife over his head. They barely escape, and as he watches them drift away his face crumbles and he gives this…not even a scream, but a soulless, animal howl.

It’s utterly terrifying and helped in no small part by Walter Schuman’s score, the scariest movie theme I’ve heard since John Williams had to fill in for a faulty animatronic shark.

The kids float down the river while Harry pursues them on horseback, a relentless, tireless silhouette against the sky. While sleeping in a barn John wakes to hear Harry singing softly in the distance and murmurs, less with fear than weary resignation “Don’t he ever sleep?”

Billy Chapin, who plays John, is honestly fantastic in this. He was only eleven at the time but he’d already won a New York Drama Critic’s Award and was one of the most accomplished child actors of his day. And in answer to your questions “drugs or alcohol?” the answer is “both” but he left acting, did a stint in the marines and then got married and had three children so, y’know, could have been a lot worse.

The two children continue on their journey through a Depression blighted countryside. They finally wash up at the farm of Rachel Cooper, played by Lillian Gish. Gish was an icon of the Silent Era until the pictures got small (and has a good claim to be being the first American movie star, period), but by 1955 she was semi-retired. What I find wonderful about that is that the movie draws so much of its magic from the fact that Lillian Gish, queen of the Silent Era, has a wonderful voice.

When this movie first came out it was lambasted by many religious groups such as the Legion of Decency and the Protestant Motion Picture Council. I consider that a spectacular own goal because, for my money, it’s one of the greatest Christian films ever made, right up there with Pasolini’s The Gospel According to Saint Matthew and Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc. And that’s down to Rachel Cooper, the most positive depiction of an explicitly Christian heroine I can ever recall seeing. The movie places Cooper as the light to Powell’s darkness, the truth to his lies. Where he is all charm and smoothness she is brusque and prickly. But she is also tirelessly kind, loving, forgiving and utterly fearless in the face of great evil.

Ever since losing her own son, Rachel has taken in every orphan she can find, and gives John and Pearl a place to stay. John doesn’t trust her at first, but finally begins to let his guard down. When Harry shows up at the farmhouse she’s instantly suspicious. Powell tells Rachel that he’s the children’s father and Rachel calls Pearl and John. John tells her that Harry isn’t their father and Rachel snaps “No, and he ain’t no preacher neither!” and politely asks Harry to leave.

Night falls.

Harry Powell waits outside the house while the children sleep.

Rachel Cooper, gun in hand, stands watch over her charges.

“And the dragon stood before the woman which was ready to be delivered, for to devour her child as soon as it was born.”

Want to see what a perfect scene looks like?

Powell sings the hymn Leaning on the Everlasting Arms, (“Leaning, leaning”) and Rachel responds with the alternate version (“Lean on Jesus, Lean on Jesus”) a name which Powell, for all his pretence at being a preacher, never once speaks. The scene transcends the simple set-up of a homesteader protecting her house against an intruder and becomes something quite mythic. You feel like they’ve always been there, these two, and always will be. Singing to each other across the darkness with weary familiarity. The false preacher and the true believer. The darkness and the light. The hunter, and the guardian.

One of the girls in Rachel’s care comes by with a candle which causes Harry to become invisible through the blinds which is the only opportunity he needs. He breaks into the house but is shot by Rachel and retreats, howling, into the barn. The next morning she calls the state troopers who arrive to arrest Harry.

If I had to find a single flaw in this thing (and I reckon that’s kinda me job) the movie has one of the state troopers ask Rachel why she didn’t call them sooner she jokes “didn’t want you trackin’ dirt over my clean floors” which is an example of a screenwriter spotting a plothole without knowing how to fix it*.

The troopers arrest Harry and handcuff him on the ground in a way that perfectly mirrors the arrest of John’s father. John breaks down in tears and starts beating Harry with Pearl’s doll until the money is raining down over them, all the while weeping “Here! Here! Just take it!”

At Harry’s trial, John can’t bring himself to identify Powell as his mother’s killer. Regardless, the Reverend is sentenced to death for *checks notes* TWENTY FIVE MURDERS MY GOD and the Spoons and the rest of the town who were eating out of his hand are there baying and howling for his blood. While the rest of the townsfolk form a lynch mob, Rachel Cooper gathers up her charges and quietly takes them home.

The movie ends with John and Pearl spending their first Christmas with Rachel and their new foster siblings. The world outside is a flurry of brilliant white snow in a movie that has been, until now, draped in inky shadow. Rachel watches her children playing happily and murmurs: “Lord save little children. The wind blows, and the rains are cold. Yet they abide. They abide, and they endure.”

***

Guys, I don’t know what else I can say. A masterpiece, and one of my new favourite films.

NEXT UPDATE: 10 September 2020

NEXT TIME: September sees the return of Bats versus Bolts! And for our next installment we are going old school. Really old school.

* The solution is to establish that Rachel either doesn’t have a phone or have Harry cut the phone line. Then, once he’s cornered in the barn, have Rachel send one of the older children running to town to get the police.