Silvio Lorusso's Blog, page 4

June 15, 2020

NPC.CAFE, Texts on Videogames

Gui Machiavelli and I didn’t really know where to publish our weird takes on videogames so we came up with our own text repository. It’s called npc.cafe because non-player characters are our friends. When I say ‘text’, I mean it: no images whatsoever, except for a bunch of emojis. It’s either read or play.

The text on Angry Birds vs Flappy Bird is quite connected to The User Condition’s posts, so if you’re into that, make sure to check it out!

May 13, 2020

The User Condition 06: How to Name Our Computer Monoculture?

A general question, to start with:

What are today’s socio-technical conditions embedded in hardware and software that shape a computer user?

There are various issues that make such question too broad. The first has to with the word computer: a Roomba, a Raspberry Pi and the laptop I’m using right now are all computers. In this respect, I tried to refine the question by offloading the problem to Google Images. According to it, the computer user is one who uses either a laptop or a desktop. I think such framing is reductive as it excludes the computer device that is most used nowadays: the mobile phone. So, the computer I’m talking about is an explicitly pseudo-general purpose device (pseudo- ’cause smartphones often need jailbreaking) which can be on one’s desk, lap or pocket. Problem solved.

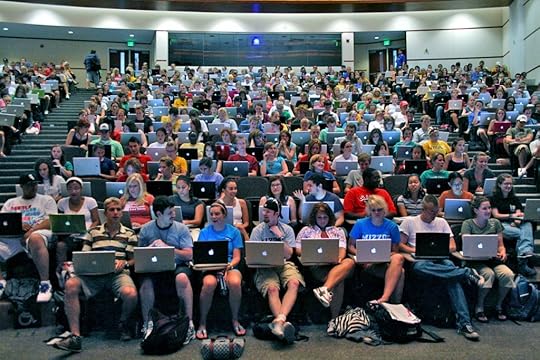

The second problem has to do with the socio-technical conditions. Those can be so widely different, that might be impossibile to make a generalization. And yet, generalize we must if we want to be able to interpret things. If we don’t, we will be stuck believing that each computer experience is different and unique. How to go about with this? In my mind I can easily picture the portion of reality I’m referring to, which is more difficult in words. Actually, this picture is not just in my mind. Here it is:

What do you see? Apple (almost) everywhere. Am I then concerned with the (declining) Apple hegemony? Not really. These people might be busy ordering stuff from Amazon, checking Facebook or writing their paper in Microsoft Word. So, Big Tech, the GAFAM, is what I mean! Nope. The range of experience I want to indicate is broader than this and yet identifiable as one. It includes the GAFAM, the user interface of Instagram, the push notification, the “pull to refresh” behavior, the expectation that a note written on your phone will be also accessible from your laptop, the Tik Tok hype and the Facebook tedium, the App Store and Google Play, the new release of Mac OS, Twitter Bootstrap, Mark Zuckerberg saying that VR is the future, your friend’s surprise when they find out you don’t have a Whatsapp account, and the list can continue indefinitely. This very blog, with its Medium.com clone layout, is part of this.

This portion of reality, this culture, can not only be described cumulatively, as I just did, but also negatively, namely, by pointing out what is not. One name comes to mind: Richard Stallman. The way he does his computing is antipodal to this culture.

I’m pretty aware I didn’t do a great job in explaining what I mean, but I’m confident I gave a good sense of it. And things are not black and white: are Slack or Twitch part of this culture? I’m not sure.

I believe that a good way to speak of something is to name it. So here’s some names:

Mainstream Computing

the Anti-Stallman

the Technium (in Kevin Kelly’s words “the greater, global, massively interconnected system of technology vibrating around us”, brr)

GAFAMondo

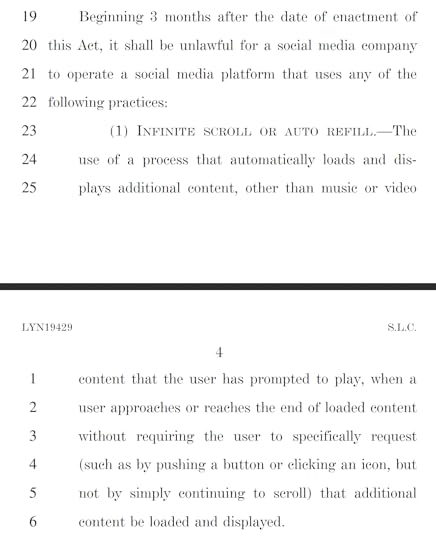

The Generalist Software-Hardware Continuum

The IThing (from the horror movie)

Normie Computerdom

Platform Consensus

Computer Convenientism

Hegemonic Computing

Platform Defaultism

Impersonal Computing

None of them is satisfying. A few might sound derogatory (Normie Computerdom), some too obscure (IThing), or too narrow (GAFAMondo). Some are just silly (the Anti-Stallman). Most of them simply don’t sound good. However, among these there is one that, as Fionnáin pointed out, has potential: Computer Convenientism. I’m reminded of a 2005 essay by Paul Graham:

Near my house there is a car with a bumper sticker that reads “death before inconvenience.” Most people, most of the time, will take whatever choice requires least work. If Web-based software wins, it will be because it’s more convenient. And it looks as if it will be, for users and developers both.

This term has the advantage of suggesting a rationale for today’s computer culture, or more precisely, monoculture, as David Benqué suggested. The rationale is an economic, efficientist one. It’s about seamlessness and straightforwardness. Alex Galloway puts it nicely: “There is one game in town: a positivistic dominant of reductive, systemic efficiency and expediency”. Makes sense to me.

I turned to the Fediverse for help and I generously got some nice ideas (thank y’all!), each one valid in its way because it highlights one of the aspects of such monoculture. Examples of that are Human-Centered Hells or The Californian Cloud Consensus by rra. Both of them emphazise the monoculture’s ideological roots in a discipline (service/interaction design) and in a specific part of the world (California).

I end this list, which you find in full at the bottom, with Brendan Howell’s proposals, that are so vivid that don’t need commenting:

The Valley of Wretched Conformity

Commodity Cameraderie

General Acceptance Fault

Virtual Suburbia

Inhuman Resources

The Motherfucking Shitstack

Instead of choosing one term once and for all, I’m going to briefly discuss some qualities of the monoculture these terms are meant to signify.

Hardware + Software: the monoculture involves both. I think for instance of the relationship between the Kindle as device and online Kindle Store.

Present + Future: the monoculture takes place now, but it includes more or less plausible visions of the future. I think of the VR picture with Mark Zuckerberg.

Platforms + the Rest: they play a big role in shaping the monoculture and therefore users’ conditions. I think of how much the current appearance of the whole web has been shaped by Bootstrap.

UX UI IT HCI, etc.: lot of autonomous fields contribute to the monoculture

Tecnologies + Practices: the monoculture is not just about the way things work but also how are they used, not used, or expected to function

Full list

Mainstream Computing

the Anti-Stallman

the Technium (in Kevin Kelly’s words “the greater, global, massively interconnected system of technology vibrating around us”, brr)

GAFAMondo

The Generalist Software-Hardware Continuum

The IThing

Normie Computerdom

Platform Consensus

Computer Convenientism

Hegemonic Computing

Platform Defaultism

Computer Monoculture

The Valley of Wretched Conformity

Commodity Cameraderie

General Acceptance Fault

Virtual Suburbia

Inhuman Resources

The Motherfucking Shitstack

Abilene Computing (from the Abilene paradox)

Human-Centered Hells

Californian Cloud Consensus

Computational Realism

May 11, 2020

The User Condition 05: On Movement and Relocation

In a previous post I stated that one of the features of interface industrialization (and therefore of user proletarianization) is “movement without relocation”. Here I’d like to characterize a bit better what I mean this two terms, especially the latter, and how they apply to computer software.

Automated Depletion Strategy by Josh Katzenmeyer

I guess it’s unavoidable to mention the very word cybernetics, coined by Norbert Wiener in 1948, which comes from the Greek kybernḗtēs, standing for the “helmperson” of a ship. The helmperson drives or better governs the vehicle. Here, the emphasis is more on movement and trajectory than relocation. We can imagine this ship traversing a boundless sea with no island and still have a sense of this activity of governing.

Let’s fast forward 20 years and we have already proper simulation of both movement and relocation on a computer screen. Doug Engelbart is known (unfairly, because his vision was way bigger than that) to have invented the mouse. To invent the mouse means inventing the mouse pointer as well. The mouse pointer can be understood as a body navigating a 2D surface (I borrow this idea of the body from John Palmer’s Spatial Interface). To be fair, the text cursor, which precedes the mouse pointer, was already a simulated body producing a sense of spatiality on screen but I assume that the sense was weaker. I suspect that one has to look into the history of videogames to discover the first simulation of a body, which Palmer defines as “an element that represents a being”, on screen.

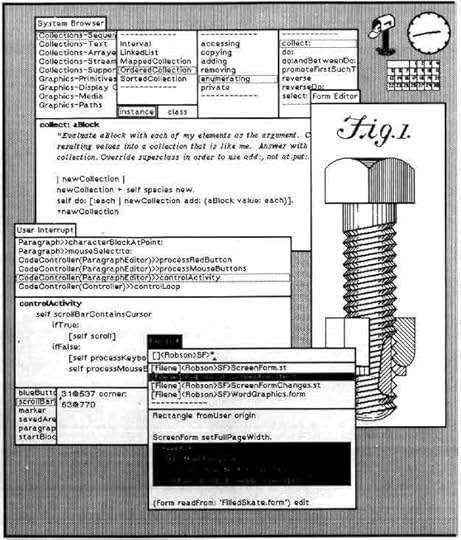

The SmallTalk development and GUI environment.

Apparently Engelbart and his team also pioneered multiple windows on a screen, but I guess it is with SmallTalk that this was refined. With multiple windows, the sense of relocation, namely movement to a different place, becomes apparent.

Finally, with the World Wide Web, another type of spatial (is this the correct term?) experience comes to the fore. One can think of browsing the web through the browser and hyperlinks as relocation without movement. Different websites feel indeed as different places, but there is the same distance between each of them: one click, which is to say that there is no distance. The Trailblazers contests are somehow the exception that confirms this norm. I’m told that according to some theorists the hypertext is not spatial, exactly because there is no distance involved, but then how to explain all the web-related spatial metaphors such as information superhighway, portal, city, surfing? Teleporting is for us an apt metaphor because, while it admits that there is a distance, it makes such distance irrelevant and imperceptible. One knows that has traveled somewhere because of the simple fact that they are in a different place: again, relocation without movement.

To conclude, I’d to advance an hypothesis, guided by a premise: metaphors are not just a self-contained product of the simulation, but are influenced by what is external to it. In other words, I’m suggesting that the sense of movement and relocation is also shaped by one’s physical movement and relocation. So, here’s the hypothesis: with the spread of mobile devices, the sense of on-screen movement and relocation has become faint. I think of the commuter checking Instagram or the email on the subway, or the traveler whatsapping with their partner on a plane. When everything around us is on the move, we might tend to project stability into the simulation, and perceive it as a persistent harbor that doesn’t change when our physical surroundings change. In a way, this hypothesis is reflected by the motto “home is where wifi is”.

April 28, 2020

The User Condition 04: A Mobile First World

Nowadays, computers can be found inside cars, fridges and watches. So, what do we envision when we think of a computer user? Google Images will provide you mostly with images of people sitting in front of a laptop or desktop computer, somehow confirming the concern that the computer, in the very moment when it becomes truly pervasive, disappears not only from sight, but also from the imagination. Here, I want to briefly argue why the most productive conception of a computer user today is that of a smartphone user.

“Computer user” search on Google Images.

The first reason is quite banal. Nowadays, people spend most of their computer time in front of a smartphone rather than in front of a PC. In the US, for instance, desktop/laptop time was more or less equal to mobile time in 2013 (~136 minutes). In 2019, the former has slightly decreased while the latter has increased quite a lot (~203 minutes), which also means that people spend more of their time on a computer. In emerging countries, smartphone usage is replacing PC usage, as shown by Robert McGovern. As he puts it, “there’s no doubt that mobile is eating the web”. Furthermore, in the US, a person is more likely to possess a mobile phone than a desktop computer (81% vs 74% in the US according to the Pew Center). I suspect that globally the discrepancy is higher.

Finally, I believe is becoming more and more common that one’s first encounter with a computer is with a mobile phone rather than with a PC. I see this happening on both sides of the age spectrum: the elderly learning to use a smartphone for the first time and that of kids doing their first experience with a mobile or a tablet at a very early age.

In 2013, Michael J. Saylor pointed out that “currently people ask, ‘Why do i need a tablet computer or an app-phone [that’s how he calls a smartphone] to access the Internet if I already own a much more powerful laptop computer?’. Before long the question will be, “Why do I need a laptop computer if I have a mobile computer that I use in every aspects of my daily life?’” If we are to believe the CNBC, we must admit he was right. Their recent title was “Nearly three quarters of the world will use just their smartphones to access the internet by 2025”.

If we take all of this into consideration, having in mind mobile phones rather than PCs when we talk of computer users seems both more adherent to the times and more inclusive.

But there is something else I’d like to mention, that is, the influence of smartphones usage on the interface design of PCs. The most obvious case in point is web design. When it becomes clear that sites are mostly accessed via smartphone, more effort will be put in apps and mobile designs. A blatant example of this is Instagram, which desktop version is very limited, not to say crappy.

The “mobile first” rule has been a mantra of web design since 2010. Mobile first means beginning the design process from the most limited and low-function browser and then gradually add visual complexity, effects and interactivity. This approach is called “progressive advancement”. More often than not, there is not enough time to give the same amount of care to every device, so the device that comes first will influence the design on the others as well. I suspect that the frequent layouts with big fonts and a single column are a result of the “mobile first” mindset.

But I’d like to suggest that the “mobile first” influence goes beyond web design. As soon as mobile phone use becomes more frequent than PC use, or it becomes the environment where one learns how to interact with a computer, certain patterns of behavior specific to the former start shaping the latter. For now, I can only bring an empirical observation to the table. I noticed that most students I work with often have a single full-screen window on their screen. They don’t seem to take much advantage of the complex spatiality afforded by their high resolution laptop screen. This might have to do with Mac OS, which encourages full screen mode via the green button on every window. This feature felt very weird to me when was introduced. In fact, I still alt + click to expand the window, as I don’t understand what I gain by hiding the topbar and the toolbar.

April 20, 2020

Intervista di Alessandro De Vecchi: design come adolescenza, deprofessionalizzazione, artigianalità digitale

Alessandro De Vecchi studia design al Politecnico di Milano. Per la sua tesi mi ha posto alcune domande sulla questione professionale, i progetti self-initiated, l’automazione, Instagram e il rischio imprenditoriale.

ADV: La tua formazione nel graphic design guida gran parte del tuo lavoro di ricerca, in quanto settore emblematico nell’industria creativa quando si parla di imprendicariato. In un saggio del 2017 sottolinei come parlare di graphic design come linguaggio ne farebbe emergere la componente ideologica, invece di parlarne in termini soluzionisti, come spesso invece viene fatto. Inoltre, sottolinei come la strada politica possa essere una strada per riaffermare il ruolo intellettuale del designer. Nell’ottica di innescare questa riaffermazione del ruolo intellettuale, credi che la strada politica sia l’unica strada? Ci sono collegamenti con il tema del linguaggio, dato che lo colleghi al tema dell’ideologia?

SL: Innanzitutto andrebbe discusso il valore di un eventuale affermazione o riaffermazione del designer come intellettuale. A distanza di alcuni anni dalla pubblicazione di quel saggio mi rendo conto che l’intellettualizzazione stessa sta al cuore del problema. Con essa intendo la produzione di un’immagine del designer quale detentore di una certa influenza culturale. Non esiste il designer; esistono i designer. Tra di essi i designer-intellettuali sono pochi. Tutti gli altri sono quasi del tutto ininfluenti a livello di discorso pubblico. Ed è proprio qui che si innesta il discorso politico. La politica che auspico è una micropolitica del lavoro, focalizzata su istanze specifiche come il reddito, il tempo di lavoro, la questione abitativa. Ciò è l’esatto opposto dei tentativi perlopiù fallimentari di lobbying professionale, come il tema dell’educazione del pubblico alla cultura progettuale. Per fare politica i designer si devono spogliare della propria veste professionale e disciplinare. Devono porsi non come progettisti ma come lavoratori della conoscenza. Devono allearsi e riconoscersi con mondi a loro estranei piuttosto che cercare di distinguersi da essi.

ADV: Il designer della comunicazione contemporaneo cerca spesso di ottenere i suoi personali successi altrove rispetto alla pratica commissionata da un cliente. Se nel passato i grandi “pezzi” di graphic design erano spesso lavori per grosse aziende, oggi sembrano invece nascere in contesti autoreferenziali verso il design stesso. Come spieghi questo fenomeno? Credi che in qualche modo alimenti un’opposizione tra il design come disciplina e il resto del mondo? Può il designer ridefinire il proprio ruolo smettendo di parlare di design e imboccando invece una strada politica che gli consenta di partecipare a dibattiti al di là della disciplina stessa?

SL: Percepisco due questioni relative al fenomeno dell’autoreferenzialità. La prima ha a che fare con la produzione di identità: le scuole di design non sono più principalmente luoghi di riproduzione professionale quanto piuttosto fucine di formazione identitaria e attitudinale. Il contesto scolastico permette di materializzare i propri interessi culturali e sottoculturali, gli hobby, il proprio essere nerd. È l’occasione per trasformare tutto ciò in un portfolio di progetti. Non c’è nulla di male in questo, però mi pare giusto evidenziare questo sviluppo che definirei adolescenziale. L’adolescenza è per sua natura autoreferenziale e riflessiva: è incentrata più sul sé che sul mondo. La seconda questione, quella della natura del “politico”, deriva direttamente dalla prima. Il politico è una delle varie forme di produzione identitaria che avvengono all’interno delle scuole. In Olanda il politico è un feticcio, un requisito formale, una norma. A proposito di ciò nel 2018 ho parlato di “politica ornamentale”: lo slogan antagonista, l’approccio attivista, i grandi temi e le grandi narrazioni assurgono a decorazioni di una pratica in fondo puramente formale e autonoma, ovvero recisa, essendo i primi spesso svuotati del loro contenuto e astratti dal loro contesto storico e sociale. Spesso – non sempre – il politico nel mondo del design è ridotto all’equivalente della spilletta di Che Guevara sullo zaino Invicta.

ADV: Sono molti gli studi e i report che definiscono i lavori creativi come “salvi” dall’imminente automazione, o al massimo posizionati relativamente in basso nelle classifiche. In realtà fenomeni come Fiverr dimostrano come la differenza tra ciò che è automatizzato e ciò che non lo è sia sempre più confusa e difficile da comprendere. Le piattaforme, gli algoritmi e le interfacce stanno portando il designer della comunicazione ad un destino ben peggiore della semplice sostituzione da parte delle macchine? In che modo, secondo te, tali fenomeni trasformeranno la professione?

SL: Il destino del designer non è diverso dal destino del lavoro in generale: polarizzazione di un mercato duale. Da una parte una piccola minoranza di progettisti lautamente pagati e gratificati da commissioni importanti e di largo impatto (mondo della cultura, del branding e della tecnologia), dall’altra un esercito di esecutori impegnati in catene di lavoretti semi-automatizzati o artigiani-autori che sbarcano il lunario dividendosi tra progetti autonomi di stampo identitario e progetti senza identità, ovvero quelli che non figurano nei portfolio ma magari sono retribuiti meglio dei primi.

ADV: In Entreprecariat dedichi alcune pagine all’analisi di LinkedIn come piattaforma in grado di alimentare la retorica dell’imprenditorialità ed allo stesso tempo influenzare l’intero mondo del lavoro in termini di relazioni, contatti e competitività. Un profilo Instagram ben curato, nell’industria del graphic design, funziona a volte meglio di un sito web personale o di un cv ricco, in quanto i propri progetti, ben presentati, sono incorniciati da elementi dell’interfaccia che ne elevano la qualità (chi ha messo like, chi ti segue, la possibilità di contatto immediato in modo informale) quasi a creare una figura di designer-influencer. Pensi che Instagram abbia cambiato la disciplina del graphic design e il designer stesso, come?

SL: Credo che Instagram abbia avuto una forte influenza, a partire da ciò che tu sottolinei, ovvero il designer reso social media manager del proprio brand. Tuttavia, c’è un altro aspetto che a me sta più a cuore. Instagram (e prima di esso Behance) ha ammazzato il sito personale. Quest’ultimo veniva generalmente progettato e programmato dal designer stesso. Il sito personale non era né un social media né una piattaforma bensì rappresentava una pratica sociale: offriva l’occasione di sperimentare con il medium del web, magari reinventandolo, tracciando attivamente le relazioni con i propri alleati: il sito personale includeva spesso una pagina dedicata agli “amici”. Ora tutta questa cultura artigianale è scomparsa (spero che qualcuno ci scriva una tesi al riguardo), i siti personali non li guarda più nessuno, e il designer della comunicazione attivo su Instagram ha rinunciato a quello che era anche un modo di distinguersi dall’utente generico di questa piattaforma.

ADV: Hai parlato approfonditamente del concetto di rischio in senso imprenditoriale, per cui colui che se lo assume viene elevato spiritualmente rispetto alle persone comuni. L’imprenditore però deve attuare una serie di strategie per cercare di ridurlo al minimo. Anche in ambito creativo infatti il “rischio” nella letteratura viene sempre trattato in ottica di “risk management” e “riduzione del rischio”. Come possibile strada per spezzare le logiche imposte dall’algoritmo e per indagare invece nuovi sentieri, può esistere un rischio incentivato piuttosto che ridotto? Un rischio inteso come atteggiamento da includere nella propria practice e in grado di innescare così processi inattesi. Un rischio inteso come innovazione sociale e politica, come strumento per dare uno strattone sia al singolo progetto di design della comunicazione sia a tutta la disciplina.

SL: Il paradosso sta nel fatto che il rischio si è normalizzato, l’eccezione si è fatta regola. Si rischia strategicamente entro una cornice concettuale che resta inalterata: rischio come investimento e strumento competitivo. Non so rispondere a questa domanda dato che il mio percorso non è stato caratterizzato da grossi rischi. Tocca forse immaginare il processo inatteso di cui parli e tentare di innescarlo tramite reverse engineering. Ciò che non mi aspetto ma mi auspico è la sovversione di un sentimento di disillusione e disincanto, che io ritengo generazionale, di cui mi sono fatto testimone. Come reincantare la propria attività? Come sentirsi meno inadeguati? La disciplina e il contesto professionale non sono in grado di offrire una risposta, anzi contribuiscono inconsciamente a esacerbare questa condizione. Le risposte vanno cercate fuori dalla sfera dell’“identità professionale”. È necessario raggiungere una posizione eccentrica per rivolgere uno sguardo impietoso verso la professione. Forse da questo punto di vista ci si renderà conto che la professione è un idolo ormai privo del suo alone di sacralità.

April 17, 2020

La regola di A G Fronzoni

[Articolo pubblicato su Progetto Grafico #35. Il Pdf dell’articolo è scaricabile qui.]

Il lavoro di Fronzoni è spesso accolto con fanatismo, ma c’è chi guarda con sospetto al suo purismo monastico. Tuttavia entrambe le fazioni hanno assorbito il suo insegnamento più di quanto credono, dato che questo consiste non tanto in una lotta contro l’inessenziale, quanto in un’ortopedia operata sulle cose, su se stessi e sugli altri.

Tra i progettisti grafici italiani attivi durante il secolo scorso, A G Fronzoni è colui che più radicalmente ha tenuto fede alla missione moderna: quella di innalzare la progettualità a principio di vita fondamentale. Attraverso un’attività che può essere considerata una lunga serie di esercizi, Fronzoni ha inquadrato lucidamente l’analogia tra design e pratica ascetica, ovvero tra progetto delle cose e progetto del sé, offrendo un esempio da imitare a generazioni di designer. È forse questa la vera ragione del culto particolare che avvolge la sua vita e il suo lavoro, un culto che va oltre l’intensità e la coerenza di un’opera talvolta in contrasto con i rigidi precetti del modernismo. In questa sede mi ripropongo di indagare, purtroppo soltanto tramite fonti secondarie, la dimensione ascetica presente nel lavoro del progettatore Fronzoni (come amava definirsi) soffermandomi sul rapporto tra progetto delle cose, progetto del sé e progetto degli altri.

Il progetto delle cose

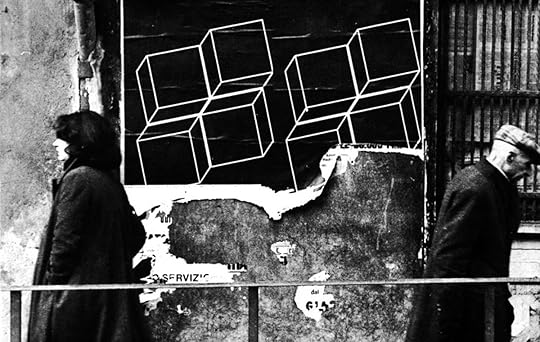

A G Fronzoni, poster per la serie “Arte e Città”, 1979. Autore della foto sconosciuto.

Durante una carriera che si è svolta principalmente a Milano, Fronzoni si è distinto per una vasta produzione di marchi, riviste, allestimenti e oggetti, tra cui l’iconica serie ’64 in tubolare metallico. Il culmine della sua opera lo troviamo però nei manifesti – cinquanta dei quali popolano la collezione permanente del Museum of Modern Art di New York – e nell’esercizio della didattica, che ha avuto luogo dapprima presso la Scuola Umanitaria di Milano, dunque all’ISA di Monza, poi all’ISIA di Urbino e all’Istituto di Comunicazione Visiva di Milano, e infine nella scuola-bottega da lui stesso fondata nel 1982 in via Solferino a Milano. A proposito dei suoi poster Fronzoni afferma:

«Per progettare un manifesto bisogna partire dall’architettura e, ad essa, tornare». Il manifesto è dunque spazio, abitato da alcuni elementi (generalmente pochi) in relazione tra loro, e struttura, come dimostrano le fustellature e le appendici cartacee che ne costituiscono alcuni. Come mi fa notare il ricercatore Michele Galluzzo, Fronzoni ha visto l’emergere di nuove tecniche di stampa e di disegno, così come ha vissuto la diffusione pervasiva della pubblicità accompagnata dalla crescente egemonia della televisione. Sebbene si sia interessato a questi sviluppi e ne abbia tratto degli esperimenti, Fronzoni non se n’è lasciato sostanzialmente distrarre e in tal senso la sua opera appare come la dichiarazione di universalità di una pratica senza tempo.

Non sembra però sufficiente limitarsi a questi aspetti formali. Avanziamo dunque l’ipotesi per cui il manifesto abbia una duplice funzione. In primo luogo è la palestra entro cui il progettista si allena, cimentandosi nella sua lotta contro l’inessenziale, che in quanto spreco è immorale, osceno. In secondo luogo il manifesto è strumento di riforma del mondo, o meglio di purificazione, difatti i poster perlopiù vuoti e acromi di Fronzoni vanno a coprire, e dunque emendare, pezzi di mondo. Dato che ormai questi poster abitano soltanto gli ambienti asettici della galleria o del catalogo, non è facile legittimare la nostra ipotesi. Una piccola conferma ci è però data dal manifesto per la mostra di Fontana alla Galleria La Polena di Genova. Fronzoni omaggia il celebre taglio dell’artista che fa della tela una superficie da varcare producendo così un oltremondo. Ci viene inoltre in aiuto una fotografia del 1979 che mostra i manifesti affissi su un muro di Genova, semilacerati: forme geometriche fluttuanti su uno sfondo nero sembrano appartenere a una dimensione platonica che si rivela attraverso uno squarcio. Sono le logiche geometrie del manifesto a coprire il disordine del mondo o viceversa è il caos delle cose che impedisce all’ordine nascosto di emergere? Un gioco di profondità palesa un orientamento verticale: ricoprire vuol dire al tempo stesso disvelare. È Fronzoni stesso, in uno dei suoi rari scritti, a parlare a proposito del bianco e nero, di «nuove e insospettate realtà» che ricordano i misteri celesti del cielo notturno.

Al Fronzoni grafico viene spesso rivolta un’osservazione critica, quella di aver privilegiato una committenza culturale “illuminata” a scapito di un mercato “reale”, perlomeno per quel che riguarda la sua attività riprodotta nelle mostre e nelle monografie. Sarebbe riuscito Fronzoni a preservare il suo rigore formale se avesse allargato la sua clientela? – domandano i critici. Ammesso che si tratti di una critica fondata, essa confermerebbe la vocazione ascetica dei manifesti di AG, che non solo mettono in scena una separazione dal caos, ma esaltano ciò che è cultura, e in quanto tale valore sì da diffondere, ma anche da preservare. In questo senso l’attività di Fronzoni è secessionista: i suoi manifesti inscrivono un mondo nel mondo, quest’ultimo in qualche misura separato dal primo. Fronzoni aspirava a «fare pubblicità alla cultura», e questo è lo scopo dei manifesti di Genova. Ma di che cultura si tratta? I manifesti danno forma a una cultura fatta per essere contemplata e assorbita ma non certo manipolata o abitata. La cultura di Fronzoni è la misura di una distanza. Certo, «la cultura va portata laddove non c’è, in periferia, tra i più deboli» ai quali spetta però solo il compito di abbeverarsene. Ma d’altronde cos’è la cultura se non un codice per iniziati, un linguaggio esoterico? Le forme pure di Fronzoni sono il simbolo della cultura posseduta da chi è in grado di leggere, e della cultura che manca per chi non è in grado di capire. In fondo Fronzoni sapeva meglio di chiunque altro che il vuoto vale quanto o forse più del pieno.

Nonostante ciò, il grafico incitava spesso i suoi allievi a farsi ingaggiare da zii o amici per progettare un logo o un’insegna, li spronava insomma a sporcarsi le mani. Qui vediamo come progetto delle cose e progetto degli altri si intrecciano. Il fine dell’opera fronzoniana è fondamentalmente educativo: si educa il committente, si educa il pubblico, si educa se stessi. Le cose progettate e il contesto di tale progettazione sono il canale, il medium di questo impresa educativa. Le cose insegnano la coerenza che le caratterizza. Come sostiene Hannah Arendt, la sfera pubblica è costituita da cose progettate che al tempo stesso uniscono e separano. I manifesti di Fronzoni sono un esempio di questa unione e divisione simultanea: attraverso il manifesto, l’utente si unisce al committente, ma è sempre il manifesto che li costituisce come entità separate e asimmetriche. Si tratta di un’asimmetria verticale: nonostante la volontà inclusiva presente nell’opera di Fronzoni, la cosa progettata trasuda immutabilità e perciò autorità. I suoi poster per le lotte operaie non accolgono le istanze degli operai se non attraverso il filtro dell’occhio competente del progettista. Se di minimalismo si tratta, quello di Fronzoni è un minimalismo pedagogico.

Il progetto del sé

Celando il suo nome di battesimo (Angiolo Giuseppe) dietro un acronimo, il grafico dichiara: «io sono solo un marchio, mi chiamo A. G. Fronzoni» (successivamente scompariranno anche i punti). Durante la sua attività di redattore e designer per Casabella, fa lo stesso con i suoi colleghi A. Mendini e G. Celant perché «nella grafica non non c’è spazio per diminutivi, per messaggi sentimentali.» Ed è proprio Mendini, che si è poi distinto per la sua verve progettuale sacrilega e irriverente, a riportare l’episodio e tratteggiare un Fronzoni appassionatamente coinvolto nella sua personalissima lotta del bene contro il male. Una visione olistica dal forte potere seduttivo, questa, alla quale Mendini, come molti altri allievi di Fronzoni, non è stato immune. Fronzoni è definito di volta in volta ortodosso, francescano e addirittura calvinista, ma ciò non impedisce a Mendini di chiamarlo illuminista. La contraddizione tra questi appellativi è soltanto apparente: quando si fa della razionalità un dogma, attorno a essa si può sviluppare un culto dal carattere talvolta più intransigente di quello delle religioni tradizionali. A questo proposito il filosofo tedesco Peter Sloterdijk, sostenitore della tesi radicale secondo cui le religioni non sono altro che sistemi di esercizi, nota che il progresso può essere considerato una specie di conversione morbida, non radicale, «una metanoia a metà prezzo» su larga scala, che diventa a volte addirittura gratuita. Fronzoni però non si è mai contentato di un facile ottimismo tecno-umanistico, ed è per questo che la sua condotta è ascetica in senso tradizionale: separatista, distante dalle cose del mondo eppure immersa in esso; «ascesi inframondana» la chiamava Max Weber, ovvero «un’esistenza nel mondo ma non di questo mondo o per questo mondo».

A G era dunque credente: oltre a una salda fede nel progresso, le sue affermazioni lasciano ritenere che non fosse privo di un credo trascendente («quando l’uomo crea si avvicina molto a Dio»). Il suo amore per l’essenzialità sembra coincidere con una frugalità di stampo francescano (Massimo Curzi lo definisce «pauperista di natura»). Una frugalità che va a coinvolgere lo stile di vita di Fronzoni, il quale rifuggiva i beni materiali e detestava la proprietà privata, che trovava il massimo dell’eleganza nell’abito di suore, preti e frati, che con la sua divisa nera sembra voler scomparire, negarsi in quanto individuo. Quella che nei suoi progetti è una riforma del mondo non è altro che un riflesso della riforma del sé: una battaglia su due fronti.

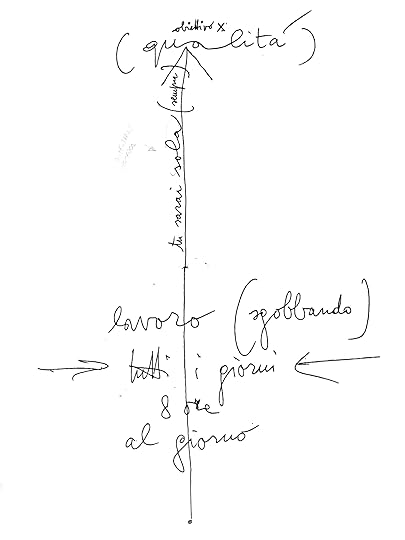

Ciò che ci resta del pensiero di Fronzoni sono principalmente apoftegmi tramandati oralmente. Gli scritti sono pochi, uno dei quali volto a castigare la vanità di chi scrive. Intitolato “Che vergogna scrivere”, consiste in un testo indecifrabile, che ancora una volta pone l’accento sulla sua forma piuttosto che sul suo contenuto. Ieratico, A G afferma che «il progetto più grosso è il progetto di noi medesimi», che «i progettatori di noi stessi siamo noi stessi, noi lavoriamo per noi». In fondo non vi è differenza tra vivere e progettare, perché «il progetto è un modo di essere, un modo di porsi nei confronti della vita e della società […]». Nel libro A lezione con A G Fronzoni di Ester Manitto, che è l’omaggio di un’allieva al suo maestro di progetto e di vita, troviamo uno schizzo a lei dedicato. Si tratta di uno schema che sintetizza la condotta del designer pistoiese. In basso, troviamo la dimensione orizzontale del lavoro e della fatica («lavoro (sgobbando) tutti i giorni 8 ore al giorno») e da questa base si innalza una verticale che punta all’altissimo obiettivo finale: la qualità. «Tu sarai sola (sempre)»: la via verticale va percorsa in solitudine, ammonisce Fronzoni.

Schema di A G Fronzoni dedicato a Ester Manitto, 1990.

Il progetto degli altri

A proposito di Fronzoni, Claudio Silvestrin, architetto e designer noto in tutto il mondo per il suo linguaggio semplice e austero, lamenta la scomparsa del mestiere di maestro. Ma di che tipo di maestro parliamo in questo caso? A G subiva certamente il fascino della bottega rinascimentale, dove si impara facendo, e in cui il maestro è innanzitutto mastro. Non si stancava infatti di ripetere il motto learning by doing, coniato da John Dewey e fatto proprio da Josef Albers nell’ambito del Bauhaus. È chiaro però che i suoi insegnamenti non si limitavano alla tecnica, andando ad abbracciare la politica e l’etica, attraverso la critica del consumo e l’elogio della cultura. Come ricorda Florencia Costa su Domus, il fulcro della sua didattica consisteva in un allenamento del pensiero, una serie di istruzioni sull’essere umano.

Ha ragione Silvestrin a dire che di maestri non ce ne sono più. Ma, dato che c’è ancora chi ha voglia di svolgere questa funzione e non manca chi ne sente il bisogno, a cosa si deve la loro scomparsa? La figura del maestro presuppone una visione delle cose limpida, definita. Il maestro detiene l’ordine. Il manicheismo di Fronzoni è certamente rassicurante, ed è per questo che fa tuttora presa sulle nuove generazioni di progettisti. Purtroppo però il culto di Fronzoni non è privo di nostalgia, e ciò lo rende malinconico. Il cenobio in cui mettere in pratica la regula di Fronzoni, già traballante quando questi era ancora in vita, ha fatto largo al deserto del relativismo e alla vertigine della complessità e dell’ironia. Abbiamo sviluppato degli anticorpi ironici che ci immunizzano dai grandi propositi e dalle grandi speranze, che ormai percepiamo come polaroid sbiadite del boom economico e post-boom (dopotutto Fronzoni è stato attivo durante gli anni 70 80 e 90, quando questo sistema immunitario si costituiva). A proteggere i fiduciosi aforismi di Fronzoni, come quelli di un Munari o di uno Steiner, ci pensa la buccia d’arancia della storia. Come risuonano le parole di Fronzoni oggi? Si può ascoltare senza tradire un sorriso condiscendente che «progettare è voce del verbo amare» (titolo di una mostra del maestro)? Oggi la sincerità di Fronzoni, prodotto di una rigorosa frugalità concettuale, spaventa e perciò si riveste di livelli, di interpretazioni, di ricollocazioni, di riappropriazioni.

Ci si imbatte spesso in una citazione di Fronzoni, di provenienza alquanto dubbia, secondo cui la sua ambizione non sarebbe stata quella di progettare manifesti, bensì di «progettare uomini». Sorprendentemente nessuno si scandalizza, forse perché tale affermazione è protetta dalla rassicurante patina di un passato glorioso. L’oscenità sta nel fatto che, in un contesto laico che pone la libertà come valore assoluto, nessuno vuole essere progettato, nemmeno dal più puro dei maestri. E chi sarebbe presuntuoso a tal punto da cimentarsi nella progettazione di esseri umani? Non si fa fatica a sentire l’eco della retorica sovietica attorno all’Uomo Nuovo.

A farci dubitare dell’attendibilità della citazione sono in primo luogo le simpatie anarchiche di Fronzoni, per cui l’autonomia è necessaria e costitutiva di un uomo degno di tale nome. In secondo luogo, l’idea di progettare uomini cozza con il più frequente e documentato riferimento allo storico dell’arte Giulio Carlo Argan, secondo cui «chi ricusa di progettare accetta di essere progettato». Eppure è proprio qui, nella tensione tra l’idea del discepolo progettato dal maestro e l’autonomia del discepolo solitario che si innesca un circolo vizioso. Il maestro-allenatore spinge a progettare la propria vita, affinché questa non sia progettata da altri; ma si tratta dello stesso maestro-allenatore provvisto di un progetto di vita da offrire al discepolo. Fronzoni incarna l’autorità che pur progettando la tua vita, ti libera, perché fa di te un progettatore.

Oggigiorno è facile ritrovare l’ambivalenza tra progettare e essere progettati nella vita quotidiana, dove si scopre che le due attività non si escludono a vicenda. La pubblicità, ad esempio, ci intima di progettare i nostri consumi e attraverso di essi la nostra personalità. Così facendo riprogetta il nostro rapporto intimo con le merci e con noi stessi. La propaganda, quando non ci manipola apertamente, fa di noi degli attori disorientati. E che dire della scuola? Tramite la scuola, lo stato progetta cittadini fungibili che devono amministrare attivamente il loro progetto di vita. In tal senso, tutte le scuole sono scuole di design. Tuttavia, le scuole di design in senso stretto generano un surplus di progettualità negli allievi, che riconsiderano o addirittura negano la propria funzione sociale. Càpita che la lezione della progettualità radicale venga accolta fin troppo bene, e si rifiuti così la vera e propria griglia concettuale entro la quale avviene l’insegnamento: si confuta l’idea stessa che l’autonomia passi per la progettualità. Altre pratiche, metodi e modalità si innescano, più vicine al continuum del diario che alla suddivisione discreta del progetto, che si configura come necessità storica di un mercato del lavoro sempre più frammentato. Gli studenti, quelli più accorti o sprovveduti a seconda dei punti di vista, ricusano il progetto, appunto per non farsi progettare. Può dunque esistere una progettualità pura, autonoma, riflessiva? Che sia indipendente dalle progettualità socialmente imposte? Se qualcosa del genere esiste, la ritroviamo nell’ascetismo radicale dei cenobiti, degli anacoreti, degli stiliti. Per tutti gli altri c’è solo progettualità promiscua, distribuita, sociale. Ci si progetta mentre si viene progettati.

Bibliografia

“A G Fronzoni ovvero dell’essenziale.” Parete, settembre 1976.

Arendt, Hannah. Vita activa. Milano: Bompiani, 2017.

Costa, Florencia. “A G Fronzoni 1923-2002.” Domus, 4 settembre 2012. https://www.domusweb.it/en/design/2002/04/09/ag-fronzoni-1923-2002—.html.

Curzi, Massimo. Inventario per autori: A G Fronzoni, “Inventario”, n. 9, luglio 2014.

Fronzoni, A G. “Che vergogna scrivere.” In Grafici italiani, curato da Giorgio Camuffo. Venezia: Canal & Stamperia, 1997.

Fronzoni, A G. “Diamo La Parola A…” C-R-U-D. Napoli, 1999. https://soundcloud.com/heather-for-c-r-u-d/diamo-la-parola-a.

Fronzoni, A G. “Il progettista grafico.” Sipradue, 5, Maggio 1965.

Galluzzo, Michele. “I grafici sono sempre protagonisti? Pubblicità in Italia 1965 – 1985.” Università Iuav, 2018.

Gunetti, Luciana, e Gabriele Oropallo. “The City as a White Page: The Encounter of Typography and Urban Space in Italian Late Modernism.” Design History Society Annual Conference, Barcelona, Spain, 2011.

Koening, Giovanni K. “Carattere di un carattere anni ’20.” Casabella, 349, 1970.

Manitto, Ester. A lezione con A G Fronzoni. Dalla didattica della progettazione alla didattica di uno stile di vita, 2017.

Mendini, Alessandro. “Colorare A. G. Fronzoni.” Abitare (blog), 28 luglio 2009. http://www.abitare.it/it/design/2009/07/28/colorare-a-g-fronzoni/.

Sironi, Roberta. “b/n. Gli spazi di A G Fronzoni.”. Doppiozero (blog), 16 ottobre 2012. http://www.doppiozero.com/rubriche/226/201210/bn-gli-spazi-di-ag-fronzoni.

Sloterdijk, Peter. Devi cambiare la tua vita. Milano: Cortina, 2010.

Waibl, Heinz. Alle radici della comunicazione visiva italiana. Como: Centro di Cultura Grafica, 1988.

Weber, Max. L’etica protestante e lo spirito del capitalismo. Milano: BUR, 2009.

April 13, 2020

The User Condition 03: User Proletarianization, a Table

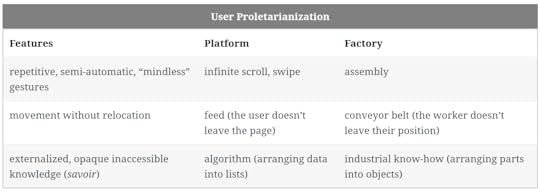

I’m posting this table, as I think it fairly elegantly summarizes what I called “proletarianization” in the previous User Condition posts. The step forward I made here is to connect the level of user gestures to that of the algorithm. The table as image can be found here.

.demo {

border:1px solid #C0C0C0;

border-collapse:collapse;

padding:10px;

font-size: 13px;

}

.demo caption {

font-weight: bold;

background-color: gray;

color: white;

.demo th {

border:1px solid #C0C0C0;

padding:10px;

background:#F0F0F0;

}

.demo td {

border:1px solid #C0C0C0;

padding:10px;

}

User Proletarianization

Feature

Platform

Factory

repetitive, semi-automatic, “mindless” gestures

infinite scroll, swipe

assembly

movement without relocation

feed (the user doesn’t leave the page)

conveyor belt (the worker doesn’t leave their position)

externalized, opaque, inaccessible knowledge (savoir)

algorithm (arranging data into lists)

industrial know-how (arranging parts into objects)

April 9, 2020

Dispatches from the Quarantine

by Silvio Lorusso and Geert Lovink

“Media: we must work together to go back as soon as possible to normality. Normality:”

During these long days, thinking is hard. Coronavirus updates come from every milieu: friends, family, work, governments, finance, the economy at large. None of them can be ignored. Remember, we used to complain about information overload. What about now? Now that we’re uninterruptedly tuned to different sources, from apps, radio, TV and newspapers, to Whatsapp chats with people in various countries and timezones. Now that our minds are busy processing the conditions and worries of our relatives and acquaintances, the selective scarcity of close-by supermarkets, the permutations of our shaky working schedules, the proliferation of software to set up. We put effort into changing our embodied automatisms, such as the urge to touch our face. In many ways, we are not ourselves.

This ain’t no time for speculation. “Instatheory” pops up and grows old in the span of a week. Are we locked, not only into our shared rooms, home-studios and apartments, but also into the present moment? Probably. And yet much of this present will be the material for the leading images and motives of the years to come. Trends are crystallizing, counter-trends are emerging. The March-April 2020 shock is a bifurcation moment, a time in which things can take completely different directions, among which there is a also cosmetic recrudescence of the ordinary. We see this in the news: what was yesterday’s “I’m shaking hands” is today’s “stay home”. What can we do then? Here, we attempt to chronicle the present: making sure that apparently minute aspects of this state of exception don’t pass unnoticed: a new habit, a novel social protocol, etc. Change is taking place at various scales, all interrelated. Subtle adjustments of everyday life accumulate. Suddenly, not recognizing this everyday life anymore, we may ask ourselves: how did we get here?

Before this happens we look at the time being to spot new behaviors that we are more or less consciously adopting, to identify social mutations that might be here to stay, to discern which ones should be encouraged or prevented.

First, some considerations. Before Coronavirus was the time of offline romanticism, time to log off, to take a break, to rediscover the fantasized authenticity of meatspace. Now, it is the time of online defaultism. Business as usual can continue thanks to smart work solutions; podcasts and live convos can broadcast conviviality; the tedium of quarantine can be overcome with a good dose of Nintendo Switch and Netflix. And yet, we feel the paucity of this networked double of social life. To be sure, the online is no less real than the offline. And yet, they are not mutually exclusive, they aren’t meant to fully replace one another. More importantly, the conversion from one to the other is not lossless. Following Franco Berardi, the conjunctive exceeds the connective.

Remote work is in many ways as concrete and corporeal than in situ work – if not more: video calls foreground the imperfections of the medium resulting in headaches and a loss of focus. Mediocre wifi disrupts the Skype-human cyborg. Remote work brings the intimacy of the family into the work scene. Remember the journalist whose live interview on BBC was disrupted by the cheerful bustle of his kids, with his wife running to catch ’em? Well, this is everyone with a family now, all the time. The messiness of life penetrates the aseptic virtuality of the digital office. We used to think of the home as a retreat from work, we now realize that work used to function as a refuge from domesticity. We speak from the position of people used to do video calls, to manipulate windows on screen, to cut and paste files, but what about the others? People who suddenly find themselves having to install software, timidly approaching a computer that is not their mobile phone, trying to orient themselves in complex spatial interfaces? Digital literacy acquires a new urgency, novel forms of digital divide emerge. Will we witness a renaissance of the desktop computer?

The lock-down comes with a software lock-in: organizations are leaning towards pre-packaged, centralized solutions. We witness the zoomification of work. Live streaming is taking over the small and busy yet simplistic interfaces of social media based on text, images and icons. Before the Coronavirus, a degree of technical informality survived. Video conferencing, notes, memos, chats… everyone could propose and use the tool or service best suited to their technical needs, ethical principles and personal idiosyncrasies. The state of exception banned this variety and with it the right to refuse certain insidious functions. “Emergency” Whatsapp groups active at every hour of the day, mandatory reports on Slack to keep the whole team updated (which few then actually read), video calls which allow to monitor the level of attention of participants.

All of these solutions have sprung up like mushrooms. It might have taken a few days to create the remote working conditions for the coming years, and they certainly don’t seem favorable. Same goes with our appearance on Zoom sessions. Apart from all the ‘selfie’ concerns of the correct face and posture, we now also have care about sound levels, background, animals and kids that come in to disturb. It is their environment, after all. Were we ever asked to comply with this intrusion of our private space? We’re not sound engineers and have no private TV studio at home. All the anxieties of the emerging Influencer Class have now, overnight, become general concerns. History has thrown us back in 2005 as our work now consists of watching ‘user-generated content’, this time produced by friends, family and fellow professionals that were not quite prepared to become ‘streaming stars’.

Covid-19 became the message so that the medium of pre-existing conditions could stay unchanged. We cried “this shouldn’t be business as usual” during the usual meetings, with the usual schedules, to the usual people. “Stop” was the forbidden word. Cultural organizations, which fundamental role is to perpetuate themselves, demanded resilience, which is to say that their atomized workforces had to implement ingenuity and flexibility. All the while, the same workforces were putting together useful lists of resources, penning open letters and signing petitions to voice their concerns. They were doing this informally, in their own spare time, to the benefit of organizations.

The organizational burden offloaded onto the workers was three-folded: organizing the very content of their work, organizing its remote form as demanded by the organizations, and finally organizing a reaction to this very form. Not even a week was lost. In schools and academies, lectures and classes continued to take place, even when it was farcically clear that a pause was due. Dutch universities lobbied to obtain the status of “vital profession”. Was this a matter of self-esteem, of dreading the idea of being irrelevant in a moment of crisis, after all the “what design can do” and “impact” kind of talk? Cultural workers whose activities weren’t postponed or “suspended” were able to stay alert, improvise, and organize work, but not to stop it. This word, “stop”, crossed the minds of many of them, a few even pronounced it out loud at the risk of appearing antagonistic or even lazy, when everyone else thought that a display of commitment was their civic duty. In this case the bifurcation was clear: stop or continue. We chose to continue.

As one could have expected, political organization in times of the Coronavirus is frantic – and yet on hold. The idea that people, once online, with spare time on their hand, would cause a revolution in cyberspace is still what it is: science-fiction. Why? Because, that very cyberspace is preventing the suspension needed to observe and analyze the situation, the interruption that we call thinking. On the contrary, we simply “adjust” to this alien situation, which means that we look at it through the rear-view mirror of the routine.

Where are the online swarms that block, hack, delete, take-over the virtual resources of the rich and powerful? Are the DDOS hordes just busy with the Italian Institute for Social Security? Is it the problem that they got sucked on Discord, or even on Slack, our rebels without a cause? What are we dreaming of here, anyway? Should we reclaim asynchronicity? Instead, we’re faced with various degrees of desperation and isolation, in which any form of wild and unexpected ‘computer-mediated communication’ is 100% not taking place. Instead, we’re trapped in the 24/7 virtual golden cages of the past, filter bubbles that rarely feel comforting.

Is it the real encounter we desire? How should we, European get there?

In solidarity, against sentimentalism.

Precarious, with worse to come.

10/04 Dispatch from Alina Lupu, Romanian Artist Based in Amsterdam

As a generally resistant person, tending to be first and foremost critical of every situation as well as hard to engage in the first stage, I find it fascinating that this reorientation towards online education in the arts has been so far reaching and so quick. When I entered art school in NL, 7 or so odd years ago, bringing a computer into a fine art environment was considered blasphemy and prompted ridicule. I had one teacher that used to do net art. Yes, net art. In the ´90s. No, as fine artists we work with our hands, we experience the material, and the material tends to be wood, clay, paint, fabric etc. I had no choice in carrying a computer with me since I was videocalling with clients (US, Australia, UK) that needed to have their websites done via some Romanian outsourcing company or another. And here we go, now we´re all digital natives and don´t frown at it. Is this evolution or the death of critical thinking? Or maybe we´re just tired… I can´t quite say at this point.

A letter of dissent started being drafted by the students of the Sandberg Institute, the Master program tied to the Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam. In it, the students, supported by their teachers and by the student unions that popped up over the past couple of years, demanded accountability from the administration of the institution after the closing of the academy and the rushed move of many of their in-person meetings and classes to open source and proprietary online platforms (Zoom is overall popular in these cases). They asked for participation in the handling of the crisis, they asked for a postponement of the academic year and refused to see their graduation show moved online. They asked for refunds of tuition fees in light of lack of access to facilities if that lack of access extended well into the summer vacation. They asked for an empathetic understanding of their condition, affected as it is by the limitations the government of the Netherlands has put on education, public gatherings and various jobs – Horeca (Hotel/Restaurant/Café) is a field in which a large swath of students was employed in order to support themselves, and much of it has been suspended. They asked for understanding in the face of the international character of the academy and the fact that many students have had to leave to their countries of origin to be close to their families during these trying times, and for an understanding of the fact that focus is hard to come by in a crisis triggered by a pandemic. These are not normal working from home conditions. Education should not be rushingly transferred into online mode, pretending to forget what triggered the move and working on the premise of “business as usual”.

The letter was signed on March 30th, 2020. It reached my inbox by mistake. It slipped through the cracks of a stuffy newsletter, due most likely to the exhaustion of whoever put the newsletter together. It wasn’t meant for public consumption, but the mere fact that it existed signaled some form of solidarity in the face of hopelessness. The letter illustrated a bottom-up change of pace.

On March 31st, the Student Council of the Rietveld Academie and Sandberg Institute went one step further, this time publicly, and took responsibility for providing what was needed during the crisis. It issued a short guide with resources for international students, artists and art workers in the Netherlands. It surprisingly broke a taboo by acknowledging the type of support needed by students in a time of crisis, practical information such as: what is a freelancer? What is a zero-hour contract? What support does the government provide in times of crisis? What should one do if their contract is not being renewed? What is unemployment and how to apply for it? How to get legal assistance? And so on.

Because it´s perfectly well to offer solidarity in the abstract and draft encouraging video speeches, but people have been plunged into the land of terminated contracts, no income, and even homelessness and under these conditions knowledge is absolute power.

But then came April 1st (sly sense of humor maybe?). The timeline that I’m building is idiosyncratic, but it´s worth maybe asking if the administration of these schools had also kept an eye on the student initiatives that went counter to the need to adapt, keep one’s head up and keep up productivity. On April 1st the Sandberg, or rather its press office, sent out a newsletter towards all of its followers, I’m guessing students and teachers included, in which it announced its “Homemade Routines”.

“How do we clean, paint, administrate, chat, prototype, stretch, cook, read, watch and dream during a period of social distancing? A growing accumulation of activities by artists and designers, live-streamed for free on Wednesdays on Sandberg Instituut Instagram, echo a different pace and concentration for our homemade behaviors.” It covered:

08:00 – Cleaning

10:00 – Painting

11:00 – Administrating

13:00 – Chatting

15:00 – Prototyping

16:00 – Stretching

17:00 – Cooking

20:00 – Reading

21:00 – Watching

23:00 – Dreaming

24/7 production.

Despite the crisis, despite the confusion, despite resistance, despite solidarity, it seems the post-autonomous artist cannot catch a break, endlessly fucked as he or she or they are by the neoliberal need to be present, to be flexible, to adapt to precarity with a smile.

April 6, 2020

Intervista di Angelica Ceccato: Sapere ombra, lock-in e rivendicazione della gratuità

Angelica Ceccato sta lavorando alla sua tesi per il Master in Estetica dell’Université Paris8. Per questo motivo mi ha posto qualche domanda su Entreprecariat, cultura digitale e creazione artistica contemporanea. Di seguito le mie risposte, in cui non ho potuto fare a meno di includere un paio di riflessioni sull’attuale stato d’eccezione.

Illustration by Studio Frames

Il libro «Entreprecariat. Siamo tutti imprenditori, nessuno é al sicuro» denuncia la condizione attuale del lavoro, in particolare quello a cui sono costretti gli agenti culturali, laddove uno status come quello del freelancer viene assimilato come una scelta di ‘libertà’, flessibilità ed indipendenza, nonostante sia troppo spesso matrice di forme di sfruttamento. In questo senso l’auto-imprenditoria sarebbe la chiave per un nuovo tipo di precarietà, che sembra sempre più accettata ed assimilata come ‘normale’ sotto le spoglie di una – non troppo sana – competitività. In questo quadro, Internet proporrebbe piattaforme in grado di accelerare questa dinamica, proponendo sistemi che spremono il lavoro cognitivo più che favorirlo ‘spontaneamente’. Esiste un modo di intendere il web come, al contrario, strumento di rivendicazione di una possibile orizzontalità dei saperi o democratizzazione della conoscenza?

Fatico a ragionare in questi termini. Se pensiamo ai gruppi ristretti presenti su piattaforme come Facebook, si possono effettivamente mettere in atto delle forme di governance pseudo-orizzontali e democratiche, dove si ozia e si lavora, si producono saperi e si scambia conoscenza. Di fianco a questo sapere di base – questo intelletto generale – ce n’è un altro, che potremmo definire “sapere ombra”. Quest’ultimo è gestito e posseduto dalle piattaforme. Esso non solo è monetizzabile ma è capace di riconfigurare i comportamenti degli stessi utenti e le loro relazioni. Esistono ambienti virtuali dove un sapere che potremmo chiamare induttivo è accessibile alle comunità di utenti (penso ad esempio a Mastodon). Tuttavia anche qui c’è la possibilità concreta di ulteriori induzioni esterne compiute su dati prodotti orizzontalmente, rese infine nuovamente inaccessibili. Parafrasando Daumal: il chiuso conosce l’aperto, l’aperto non conosce il chiuso.

Nel testo si fa appello alla misura in cui la logica competitiva del lavoro 24/7 provoca una ‘volontaria’ deprivazione delle ore di sonno. In particolare, questa istanza andrebbe ad influire sull’economia dell’attenzione, anch’essa precarizzata dalla presenza di troppi input. D’altro canto, anche Bifo afferma che il sovraccarico dell’informazione, come del troppo lavoro, e la tirannia di un vivere in aggiornamento perpetuo portano ad uno stato di «discronia», ossia la patologia del tempo vissuto eradicata nell’odierna ‘era dell’impotenza’. In particolare per quanto riguarda il lavoro online, é possibile ristabilire un equilibrio nell’attenzione o siamo destinati all’anestesia, discronia, ed anempatia come preannuncia Bifo? É eventualmente possibile riappropriarsi di una temporalità più sostenibile rispetto a quella proposta da uno ‘smart working’ che arriva a sottrarre le necessità biologiche primarie? (penso, tra le tante, all’immagine che accosta il wc al pc)

Questa domanda giunge in un momento in cui lo smart working assurge a mezzo per salvare l’economia e impedire che la macchina dell’impiego si inceppi a causa del lockdown. A me pare che il lockdown stia portando con sé un lock-in a livello di software: le organizzazioni propendono per soluzioni preconfezionate e centralizzate. Il lavoro si sta zoomificando. Prima del Coronavirus, nel mio ambiente di lavoro sopravviveva una certa informalità nei confronti degli strumenti adottati per le mansioni d’ufficio: videoconferenze, appunti, memorandum, chat ecc. Ciascuno poteva proporre e usare lo strumento o il servizio più affine alle sue esigenze tecniche, ai suoi principi etici e alle sue personali idiosincrasie. Lo stato d’eccezione ha messo al bando questa varietà e con essa le facoltà di rifiutare certe funzionalità insidiose. Sono spuntati come funghi gruppi Whatsapp “d’emergenza” attivi a tutte le ore del giorno, frequenti richieste di report per tenersi aggiornati (che in pochi hanno poi il tempo di leggere), video call in cui è possibile monitorare il livello d’attenzione dei partecipanti. Temo che ci siano voluti pochi giorni per creare le condizioni del lavoro remoto dei prossimi anni, e non sembrano certo condizioni favorevoli.

Nel testo si cita spesso il pensiero di Richard Sennett riguardo soprattutto il concetto di flessibilità, o meglio di flexploitation. D’altro canto Sennett, come Kenneth Goldsmith, é uno tra i teorici sostenitori della cultura Open, che si configura nella città aperta, ma anche nell’Open Source digitale, nel libero accesso ed alla co-creazione dei contenuti online. Un lavoratore entreprécaire, può permettersi di essere portavoce di una cultura come quella del ‘libero accesso’?

“Free” è stato il mantra degli ultimi vent’anni. Ciascuno di noi ha prodotto e consumato contenuti gratuitamente. Tutto bellissimo, in teoria. In pratica però la polarizzazione dei network attorno ai nodi più collegati ha fatto sì che questi nodi potessero beneficiare più degli altri della ricchezza prodotta dalla rete nella sua interezza. Un artista semisconosciuto produce un’opera e la pubblica discretamente online, questa viene usata come spunto o direttamente scopiazzata da un artista più noto o da un brand. Quest’ultimo ne trae profitto, mentre il primo deve sgomitare persino per vedersi riconosciutà la paternità dell’opera. Se le cose stanno così, dobbiamo diventare strenui difensori del copyright? Nient’affatto, e non solo perché il copyright è un’arma efficace principalmente nelle mani di chi ha tempo e denaro per intentare una causa. La ragione più importante è che i commons sono a tutti gli effetti un bene comune, la cultura si produce collettivamente, insomma, il diritto d’autore è una finzione giuridica. Piuttosto che proteggere le sue opere, l’ entreprécaire deve rivendicarne la gratuità, ovvero la possibilità di contruibuire ai commons contestando l’attuale regime di competitività indotto dalla scarsità diseguale.

Si può affermare che abbracciare l’’inter-dipendenza’ corrisponderebbe ad accettare (e gioire di) una sconfitta, quella dell’eccezionalismo propagandato dalla logica imprenditoriale?

Sì.

La conclusione del tuo libro propone una sorta di breve elogio all’impotenza. In generale, l’impotenza é collegabile ad un impatto negativo nell’economia dell’attenzione, come in quella del piacere, messa in crisi dalle nuove tecnologie di comunicazione – e di lavoro – come affermano Bifo o Yves Citton. In che senso l’impotenza come ascesi e rinuncia al corpo sarebbe una via d’uscita dalla precarietà? Si tratta di un’ennesima affermazione di insufficienza individuale fronte alle possibilità collettive?

L’impotenza è l’opposto dell’ascesi: la cultura imprenditoriale sollecita una condotta ascetica del corpo e della mente. Il mio breve elogio dell’impotenza deriva da una semplice domanda: se persino l’ozio e la noia sono messi a lavoro, esiste un valore (o disvalore, a seconda dei punti di vista) in grado di non essere recuperato dall’imprenditorialità? La risposta è l’impotenza. Per impotenza intendo la sottrazione radicale a ciò che l’imprenditorialità chiama “potenziale”.

Il ‘trionfo dei nerd’ nella cultura imprenditoriale sembra prevedere un’impronta tutta al maschile. Si può affermare che l’entreprecariato nell’era digitale evidenzi le differenze di genere, qualora la cultura digitale sia spesso intrisa di sessismo tanto esplicito quanto tacitamente accettato?

Se la cultura imprenditoriale, come giustamente sostieni, ha un’impronta principalmente maschile (con l’eccezione di figure chiave come Margaret Thatcher), il discorso critico sulla precarietà ha invece una forte matrice femminile e femminista. A fronte dell’attuale emergenza sanitaria, la cultura imprenditoriale ha poco da dire a parte chiedere a gran voce il ripristino delle attività. Al contrario, le teoriche della precarietà hanno saputo anticipare delle questioni che si stanno palesando con drammatica evidenza, come ad esempio la precarietà ontologica della vita e la relazione non esclusiva tra autonomia e dipendenza. In questo periodo la cultura digitale, perlomeno quella in cui sono immerso, mi pare sia più precaria che imprenditoriale e perciò più femminista che maschile.

Nel preciso periodo storico che stiamo vivendo, di preannunciato collasso ambientale, sanitario, e forse politico e militare, molti si affida alla cultura online come baluardo di rinascita ed ispirazione, basti pensare alla quantità di materiale culturale messo a disposizione gratuitamente da musei, riviste ed in generale altre istituzioni culturali. Ora che siamo tutti online, e pertanto nessuno é ancora al sicuro, si può pensare alla costruzione di una rete inedita di cooperazione che esca dagli schemi delle attuali gerarchie di visibilità in linea? O, al contrario, la maggiore disponibilità di materiale culturale non farà che fortificare gli attuali algoritmi di ricerca, favorendo la condivisione di elementi già parte del consumo mainstream (penso a piattaforme dal trend elevato come Netflix o Spotify, contro alternative indipendenti e senz’altro meno inflazionate)?

Ora che siamo tutti online, come dici tu, ciò che mi preoccupa è la questione infrastrutturale. Pare che nelle ultime settimane il traffico sulla rete sia aumentato del 20% e con esso i costi di gestione. Molte iniziative culturali affidano la loro presenza online ai giganti dell’hi-tech. Temo che scopriremo a nostre spese che l’accesso a risorse online non è mai gratuito fino in fondo.

Il ruolo dell’artista contemporaneo sarebbe, in questo quadro, quello di indagare nuove forme di pensiero, criticare (nel suo senso di messa in crisi analitica) ed ironizzare l’attuale gerarchia di produzione della conoscenza. In che modo l’artista, una figura che é essa stessa parte dell’entreprecariato (l’artista é imprenditore, ergo non é al sicuro), può attuare questa pratica metadiscorsiva?

Credo che ci sia una differenza tra ruolo e funzione dell’artista. Il ruolo dell’artista è ciò che tu descrivi: criticare, ironizzare, sovvertire, resistere. La sua funzione è purtroppo un’altra: contendersi lo pseudo-welfare che gli viene offerto sotto forma di grant e residenze; alimentare la macchina culturale di uno stato sancendone l’ampiezza di vedute; fornire un appiglio identitario a chi non sa, non vuole o non può trovare posto altrimenti nel mondo del lavoro.

March 11, 2020

The User Condition 02: A Tentative Chronology of the Industrialization of Web Interfaces (work in progress)

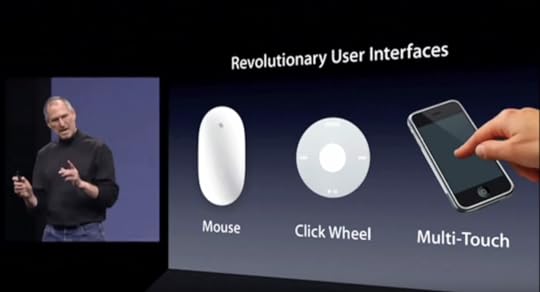

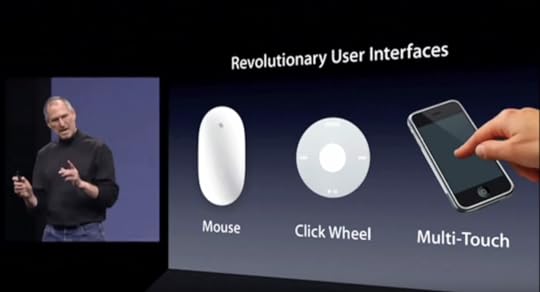

Apple’s “revolutionary user interfaces”

In a previous post, I hypothesized that the evolution of web user interfaces can be understood as their progressive automation which, following the paradigm of industrialization, produces in turn a proletarization of the user. In this post I propose a tentative chronology of technical inventions as well as future forecasts, formulations of trends, and public admonishments that have contributed to and engaged with such transformation. The term proletarization is inspired by French philosopher Bernard Stiegler. I do not use it in an accusatory or moralistic sense; by that I intend to simply point out that, by means of semi-automation first (infinite scroll), and full automation then (playlist, stories, etc.), the user is turned into a “hand” first and then into a machine operator, someone who supervises the machine pseudo-autonomous flow and regulates its modulations. Following Simondon, the machine replaces the tool-equipped individual (the worker).

There are four main intertwined threads in this chronology: the emergence of web apps, the invention of the infinite scroll, the appearance of syndication and aggregation, the introduction of smartphones and thus the swipe gesture.

As I’m sure I’m missing or misunderstanding some aspects of it, comments are very welcome. There is also a loong Mastodon thread about this. Let us begin.

1997: Netscape Communicator is launched. The software is an early attempt (the first one?) to somehow merge browser navigation capabilities with applications like email and instant messaging in a single suite. This can be seen as a step towards erasing the distinction between webpages and applications.

https://books.google.de/books?id=Kh0EAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA8&lpg=PA8&dq=#v=onepage&q&f=false

2000: Microsoft develops the XMLHttpRequest technology (the cornerstone of the more known AJAX technique later used for the infinite scroll). XMLHttpRequest (originally XMLHTTP) allows to fetch content from the web and include it into a webpage without having to reload it.

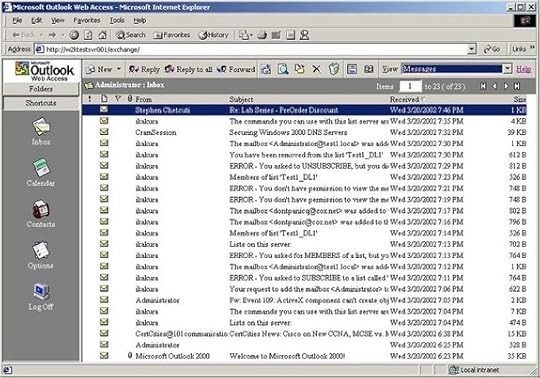

The technology is implemented in Outlook Mail. Alex Hopmann, one of the engineers involved, speaks of two competing versions of the software: “There were two implementations that got started, one based on serving up straight web pages as efficiently as possible with straight HTML, and another one that started playing with the cool user interface you could build with DHTML.” Was this a historical bifurcation moment? If so, are static and dynamic its terms?

Outlook Web Access

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/XMLHttpRequest#History

https://web.archive.org/web/20070623125327/http://www.alexhopmann.com/xmlhttp.htm

2001: Paul Graham publishes “The Other Road Ahead” essay. “There’s something wrong when a sixty-five year old woman who wants to use a computer for email and accounts has to think about installing new operating systems. Ordinary users shouldn’t even know the words ‘operating system,’ much less ‘device driver’ or ‘patch.’ […] With Web-based software, most users won’t have to think about anything except the applications they use. All the messy, changing stuff will be sitting on a server somewhere, maintained by the kind of people who are good at that kind of thing.”

Such statement, having to do with the shifting agency of ordinary users (the very topic of an upcoming post), seems very much to substantiate the proletarization hypothesis, if we think of it as the worker’s alienation from the tool. At the same time Graham points at some openings for direct, synchronous collaboration, which is antithetical to alienation:

“This is an obvious win for collaborative applications, but I bet users will start to want this in most applications once they realize it’s possible. It will often be useful to let two people edit the same document, for example.”

http://www.paulgraham.com/road.html

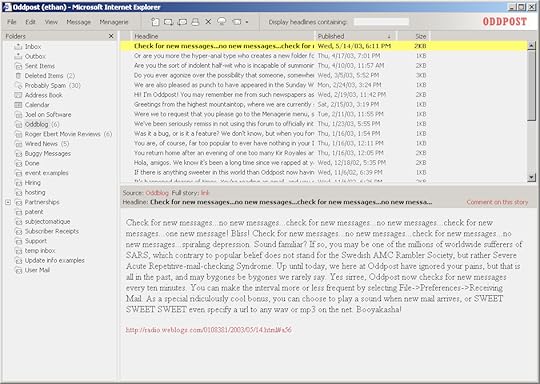

2002: Oddpost.com pioneered the use of JavaScript and AJAX to mimic a desktop mail application, making the service much faster (no reload needed).

Oddpost interface

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oddpost

2002: Dave Winer launches RSS 2.0, which propelled the growth of news and blog aggregators, normalizing the idea of a feed made of content coming from various sources.

Tiny Tiny RSS user interface

2004: Google borrows several ideas from Oddpost to create Gmail. The main developer is Paul Buchheit, while the main designer is Kevin Fox. Given the general web-centricity of Google services, Gmail turned out to be a website but AJAX “made it feel more like software than a sequence of web pages”. The original version doesn’t seem to have infinite scroll to browse the emails.

Journalist Harry McCracken puts it this way: “If you wanted to pick a single date to mark the beginning of the modern era of the web, you could do a lot worse than choosing Thursday, April 1, 2004, the day Gmail launched.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oddpost

https://time.com/43263/gmail-10th-anniversary/

2004/5: Tim O’Reilly and Dale Dougherty popularize the term Web 2.0. What, of the narrative that I’m trying to build here has actually to do with Web 2.0? Some examples extracted from the original “meme map” and Markus Angermeier’s extended map. These are interesting because they don’t necessarily confirm the industrialization trend, but even confute it sometimes. For the moment I just list them: “The Web as Platform”, Gmail and AJAX as “Rich User Experiences”; “User Behavior not predetermined”, “Joy of Use”, Syndication, Design Liveliness, Design Simplicity. Regarding RSS O’Reilly states: “RSS allows someone to link not just to a page, but to subscribe to it, with notification every time that page changes. Skrenta calls this ‘the incremental web.’ Others call it the ‘live web’.” Can it be that the liveliness now infused in the web decreased that of its users? “We’re entering an unprecedented period of user interface innovation, as web developers are finally able to build web applications as rich as local PC-based applications.””

Markus Angermeier’s Web 2.0 map

https://www.oreilly.com/pub/a/web2/archive/what-is-web-20.html

2005: Jesse James Garrett coins the acronym AJAX. “Ajax isn’t a technology. It’s really several technologies, each flourishing in its own right, coming together in powerful new ways. Ajax incorporates:

standards-based presentation using XHTML and CSS;

dynamic display and interaction using the Document Object Model;

data interchange and manipulation using XML and XSLT;

asynchronous data retrieval using XMLHttpRequest;

and JavaScript binding everything together.”

https://web.archive.org/web/20050601001457/http://www.adaptivepath.com/publications/essays/archives/000385.php

2005: Bill Scott publishes a blog post titled “Death to Paging!” where he describes the LiveGrid Behavior: “First, let me say that I really don’t believe that paging is evil or that it is wrong in all cases. But I believe the reason that most sites have paging solutions is because 1) its easy to implement, 2) handles the problem of large sets of data and 3) it is convention.”

https://web.archive.org/web/201104270...

2005: Nick Craswell, Julie Farago and Hugh E. Williams invent infinite scroll and apply it to MSN image search: “Over a pizza lunch, Nick, Julie, and I spent time digging in user sessions from users who’d used web and image search. We learnt a couple of things in a few hours. […] The first thing we learnt was that users paginate in image search. A lot.”

MSN Image Search results inteface

https://hughewilliams.com/2012/03/06/ideas-and-invention-and-the-story-of-bings-image-search/

2006: Aza Raskin also invents the infinite scroll, calling it “Humanized History”. Like in the 2005 implementation, the issue to solve is pagination. “The problem is that every time a user is required to click to the next page, they are pulled from the world of content to the world of navigation: they are no longer thinking about what they are reading, but about about how to get more to read. […] The take away? Don’t force the user to ask for more content: just give it to them.”

https://web.archive.org/web/20120606053221/http://humanized.com/weblog/2006/04/25/no_more_more_pages/

2006: Facebook launches the much hated News Feed. “Before the News Feed, you wouldn’t see a collection of updates and stories when you logged onto Facebook. You’d only get personal notifications like how many people had ‘Poked’ you and if anyone had written on your Wall. Every browsing session was like a click-powered treasure hunt: You would search for specific people to look at their profiles and then just wander through the site from there.”

https://www.businessinsider.com/facebook-news-feed-launch-2016-9

2008: Paul Irish releases the infinite scroll jQuery and WordPress plugin, which probably led to a big spread of the technique. The advantages of the plugin: “Users are retained on the site far better; Requires no adjustment in a user’s typical reading habits.” Irish also puts together his own history of inifnite scroll which features Aza Raskin, but also less official solutions such as an Auto Pager greasemonkey script for Google Search.

https://www.paulirish.com/2008/release-infinite-scroll-com-jquery-and-wordpress-plugins/