Silvio Lorusso's Blog, page 3

December 16, 2021

Addendum to Platform BK’s Open Letter to Dutch Art Academies: Economic Responsibility in Art Education

Last week I signed Platform BK’s open letter entitled “Graduates of art academies deserve more agency over their future” without hesitation. Addressing the executive boards of Dutch Art academies, the letter argues that education should prepare students for “the unruly reality of the cultural sector’s job market”.

A four-point plan is laid out: 1) developing post-precarity courses; 2) support social engagement and self-organization; 3) provide insight into the wolrd after the academy; 4) involve students in institutional developments.

The letter argues that general response to the issue of labor is two-folded: cultural entrepreneurship on the one end of the spectrum, and art autonomy on the other. The first can be understood as a passive adoption of a market logic (neoliberal, if you will) within education; while the latter is a form of romanticized detachment from the material reality of artists and designer careers’.

A previous version of the letter advocated for an “economically responsible art education”. The big question is: how do we define economic responsibility? Here, I’d like to give a pointer towards a possible answer, linked to point 3 of the letter.

Economic responsibility is not just financial literacy. Sure, students need to know how to write invoices, but economic responsibility goes beyond that. One way in which art academies can be more economically responsible is by strengthening the research into the lives of their students after graduation. The data available is often fragmented, hard to find, superficial, too broad (on the scale of a country or even a continent) and frequently comes from the work of students themselves who use their thesis time for this kind of inquiry. Furthermore, exceptionalism is the norm: cherry-picked successful alumni are invited to give career tips to young students, reinforcing biased representations of professional fulfillment. Instead of externalizing surveys and cherry-picking success, art academies should be the ones that dedicate in-house resources to develop a rigorous, localized picture of economic life after graduation.

November 15, 2021

Notes on Design Populism

Like many others, I’ve been following @neuroticarsehol for years now. Mostly popular within graphic design circles, NA is a shitposting account active on both Twitter and Instagram that makes fun of the grandiose statements of the design discourse, its unrealistic claims, its careerism, and its distance to everyday life.

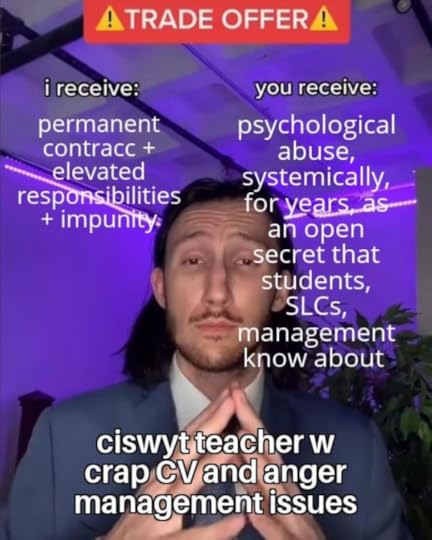

@neuroticarsehol, 2021

Not everyone likes them. Some more or less prominent practitioners find their points reductive and obvious: ethical or political gestures unavoidably contribute to a designer’s career. This doesn’t mean that these gestures are insincere and that such designer is a hypocrite. Not so long ago, I stumbled upon a starter pack meme made by the students of a German design school. Here, NA appeared behind a red cross. The meme also showed legitimate “equipment”, such as the Glossary of Undisciplined Design, and a We Should All Be Feminists shirt.

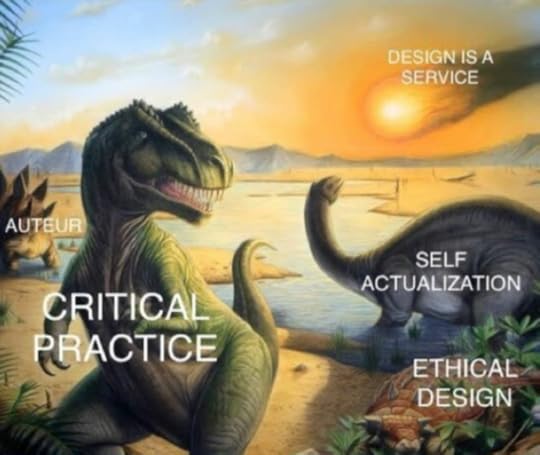

While NA starts to get “canceled” (because they’re too cynical, destructive, purely negative), I find their existence very relevant. To me, NA represents the growing distance between cultural production & consumption within the field, between main characters of the discourse and NPCs. Two developments in the field exacerbate this phenomenon: the research turn and the industrialization of education.

Consider the post at the top. It is no coincidence that it shows educators on one side and students on the other. During the last three decades there has been a crucial turn in design education (at least in many avantgarde design schools around Europe, UK and the US). Before the turn, students were mostly trained to become practitioners in a traditional sense, to think of themselves as problem-solvers, to consider design a service, to have clients or at least to work in a studio, etc. After the turn, a student is encouraged, implicitly or explicitly, to become not a technical expert that solves problems, but a cultural producer that frames problems. In other words, an intellectual, or more precisely an organic intellectual: someone who contributes to culture not only by writing books. An intellectual by other means.

The keyword here is research. In Europe the research turn has been diversified but conscious. Already in 2006, research was presented as an alternative to the proletarization of graphic design while now, in 2021, the notion of “artistic research” is at the center of a heated debate. The research promise takes place both at the level of content (methodologies, assignments, etc.) and at the level of people (educators who work predominantly as researchers and thus offer a concrete example of such career path to their students).

In the meantime, there has been an industrialization of design schools. By this, I mean that education has become one of the main industries in the design field, something that Enzo Mari already pointed out some years ago. I wouldn’t be surprised if graphic design education mobilized more money than graphic design as a trade.

The research turn can be considered a response to designers’ lack of access to the operation rooms of problem solving. Of all the highly educated designers cast by industrialized education, only a few might be able to work on fairly complex—and therefore gratifying—problems, while most might become indeed proletarized. The promise of cultural production, of research, compensates this risk.

The research turn generates a common language made of design currents identified by specific labels. A language that is highly dynamic: every year a few new labels pop up. Everyone who participates or wants to participate in design cultural production has to be fluent in these. But speaking the language is not enough. An emergent design current is not just a set of ideas, principles and values but also and especially a distinction device. It doesn’t only matter that I know what, say, critical design is, but also that my name is associated with it. When that happens, the promise is finally realized: not anymore just a cultural consumer, I’m finally a cultural producer.

How many cultural producers can there be among highly educated designers? Not many, I think. The venues for the cultural production of design (from theory-fiction to critical multimedia installations) are relatively little and generally not so well funded.

What happens then to the designers who don’t manage to become cultural producers? To them, there is not so much difference between the “tacky” social design label and the “hip” undisciplined design one, they both appear as signals of a cultural circuit inaccessible to them. The designer as cultural consumer remains a student for life.

I think it is useful to look at this phenomenon from the lens of populism, namely the tension between the elite and the people. Beware: I don’t consider populism an intrinsically right-wing manifestation, but a dialectic at play in various societal spheres. Same goes for elites, which are and will be part of society. I’m not speaking of Jeff Bezos here, but of elites that are commensurate to the context that they emerge from. An elite is not necessarily an exploitative formation, but simply a closed group of people who determines their own criteria of inclusion. Design education, even when is blatantly anti-capitalist, horizontal and the like, is doing exactly that: determining the criteria of inclusion within its cultural circle.

Dank Lloyd Wright, 2021

Similar manifestations of this populist tension take place in other fields like architecture, with meme pages like Dank Lloyd Wright, or at a different scale, with school-specific meme pages like the Dutch wdka.teachermemes (I interviewed them here). IN DLW, the elite is comprised of archistar, megastudios and ivory tower academics, while the people are precarious young architects. For WDKATM, the elite are the managers and the teachers with permanent contracts, while the people are students and flexible teachers.

Design populism is peculiar, because both the people and the elite have similar levels of education. Education is in fact key to understand the current social and economic state of design. Contra the misleading dualism of the school vs the real world, the school is the real world.

wdka.teachermemes, 2021

Things get messy when a design current is connected to notions of social justice because it becomes difficult to decouple the inherent logic of social capitalization from ethics. The very concrete risk is that social justice is dismissed as elitist, which is exactly what’s happening. Furthermore, the criteria of inclusion of social justice circles actively limit general participation. While anyone could call themselves a “critical designer”, not everyone could present themselves as a “pluriversal designer” without raising some eyebrows. It makes sense: marginalized people don’t want to be robbed once again of their social capital. However, the awareness of a closing window of opportunity might generate a novel conservatism. What does a conservative designer look like? Quite the opposite of the ironic shitposter. One who cherishes order and hierarchy. One who wants to keep politics out of the equation. Here’s Paul Rand writing in 1992:

Both in education and in business graphic design is often a case of the blind leading the blind. To make the classroom a perpetual forum for political and social issues for instance is wrong; and to see aesthetics as sociology, is grossly misleading. A student whose mind is cluttered with matters which have nothing directly to do with design; whose goal is to learn doing and making; who is thrown into the fray between learning how to use a computer, at the same time that he or she is learning design basics; and being overwhelmed with social problems and political issues is a bewildered student; this is not what he or she bargained for, nor, indeed, paid for.

Of course, one thing is when a designers who used to ask a minimum $100.000 fee say this, and another one is when a working class student says the same thing. When the latter happens, it’s important to avoid quick demonizing and take into account the populist tension I’ve tried to describe in order not to turn design education into an arena for resentful conservatism.

As soon as I have more headspace, I plan to come back to this topic and turn these notes into a proper essay. If you would like to publish such a thing feel free to get in touch.

November 3, 2021

6 Theses on the Deprofessionalization of Design

1. According to Donald Schön, a professional is someone who “claims extraordinary knowledge in matters of human importance, getting in return extraordinary rights and privileges.” This definition proves that a profession is necessarily exclusive. Claiming inclusivity by calling for a complete deprofessionalization of design is mere populism.

2. The current calls for design deprofessionalization legitimately denounce how the design profession has disproportionately excluded marginalized groups. However, they ignore the mechanisms of deprofessionalization that affect the design field in the first place. This is a problem, because higher education–which is where these calls generally come from–is bound to generate resentment and anger if it cannot guarantee to its student body, which invests time and money in its institutions, the social and economical benefits of the profession.

3. In the context of design, extraordinary knowledge is expert knowledge. We need to ask: how much of this expert knowledge does the designer actually hold in the public perception? If the designers’ knowledge is not considered, at least partly, a form of expertise, they won’t be granted the status of professionals in the social arena.

4. In the eyes of the general public, certain design sub-fields such as graphic design do not possess any “esoteric” knowledge. The perception is that thanks to the common availability of digital tools and devices, everyone can design a logo or a book. For several people the fact that there are MAs in graphic design is a source of astonishment.

5. Whether this perception is right or wrong is irrelevant, as it does and will nonetheless shape the economic relationships between clients and designers, and therefore the social status of the latter. The effects are already apparent in the salary gap between specialists in UX design, which is still considered an esoteric practice, and those in graphic design, which is fully demystified.

6. Some designers recognize that there is no fundamental difference between their supposedly expert knowledge and that of a profane. Instead of trying to convince the public of something they don’t even believe in themselves, they attempt to regain the benefits of a professional position (prestige, credibility, higher income) by placing their expertise within the domain of cultural production, i.e. by presenting themselves as intellectuals. Thus, cultural production is not just the casual ambition of some aspiring intellectuals, but the result of their field’s failure to generate or maintain the impression of expert knowledge. Ironically, the very calls for deprofessionalization belong to this process.

June 29, 2021

Other Worlds

A few months ago, I was blessed to join the amazing team of the Center for Other Worlds, a research center for design and art based at Lusófona University. Now, we’re finally launching Other Worlds, COW’s shapeshifting journal for design research, criticism and transformation. Other Worlds (OW) aims at making the social, political, cultural and technical complexities surrounding design practices legible and, thus, mutable.

What other worlds, exactly? Those that have been traditionally ignored, neglected or silenced in the past, as well as those that are overlooked today: non-Western communities negotiating their own set of values through practice; alternative rationalities emerged in the West but overshadowed by the instrumental reason; technosocial environments blossoming at the periphery of platform empires, semi-visible modes of organization that oppose or sustain official institutions.

OW hosts articles, interviews, short essays and all the cultural production that doesn’t fit neither the fast-paced, volatile design media promotional machine nor the necessarily slow and lengthy process of scholarly publishing. In this way, we hope to address urgent issues, without sacrificing rigor and depth.

We are starting small, OW’s initial form is that of a newsletter. Follow this link to find more information and to subscribe.

Do you feel like you have OW same energy? Then, don’t hesitate to get in touch!

May 18, 2021

Notes on the WdKA’s Removal of a Pro-Palestine Resistance Students’ Banner

Yesterday, a students’ banner in solidarity with Palestine was removed from the walls of the Piet Zwart Institute of Rotterdam. The Willem de Kooning Academy, whose the PZI belongs to, took out it out because “the University of Applied Sciences does not get involved in geopolitical situations” and “does not take political stands whether on national or international issues”.

This might come as a big surprise for who has witnessed first-hand the often self-congratulatory ostentation of Dutch art & design’s criticality, politicality, activist attitude, and decolonial agenda. On Instagram, two posts before the official statement, one reads: “Hello all! Tomorrow our Instagram will be taken over by WdKA’s climate collective SPIN.

”

”

Piet Zwart students expressing solidarity with Palestine.

Needless to say, the walls’ cleansing generated a social media wave of indignation. Especially after a 2015 WdKA branded initiative in support of Charlie Hebdo was unearthed. Soon, the keyword became “double standards”, indicating the institution’s eagerness to take a political position — only when such position fits the Western liberal frame and only when it comes at no reputational cost.

It is worth noticing the abyss that separates students and teachers from management. It seems that the former are relegated to “expression”, while decision-making and direct action is fully in the hands of the latter. This is why students and teachers resort to call out tactics. The call-out is the weapon of the ones who have no seat at the table.

The WdKA affair also shows the state of politics within those institutions who feel the pressure to align themselves with values and programs that they don’t fully comprehend and don’t fully adhere to. Seeing like an institution means reducing politics to “content”, to a generic posture that smoothly resonates with the metrics of relevance and urgency. Metrics that can’t be ignored, as any grant-writing artist would confirm. “Politicality” is functional to institutional legitimization, politics is often detrimental to it.

The dilemma of the coming years will be how to reconcile an art and design discourse which is increasingly entangled with specific, even antagonistic political stances with a strategic neutrality and political superficiality. In order words, how to reconcile the internal politics with external politicality. The WdKA stated that its “buildings do not serve as a platform” for political view. But the very removal of the banner platforms a specific political idea, or better, an idea of the political: the idea that politics is a matter of personal opinion, of “empowered professionals with their own views”, rather than a matter of conflict.

One should take the official statement seriously. No authentic political stance can be expected from the institution. Politics will mainly remain at the pedagogical level, that is, both the informal level of conversations and discussions and the formal one of syllabi and programs. Students and teachers might be surprised by the school’s authoritarian decision, but the school shouldn’t be surprised by their reaction. A double bind is in place: in several academies, the educational level prizes the political to the extent that nothing can escape it; while the managerial level is blind to it, or even actively against it when it goes beyond “content”, that is, when it is truly political.

[image error]April 6, 2021

Ghostly Design

The design field operates according to a fundamental conviction: that what we call design has an unambiguous existence. Back in the days, delimiting design was easy: whereas the mass-produced moka pot hissing on the stove was design, the handmade ceramic cups used to drink its coffee weren’t. Design began with the series and ended with it. Nowadays, things are more difficult: design escaped its industrial enclosure to become a mentality, which is to say that our mentality has become industrialized.1 The few handmade objects still surrounding us owe their aura to design. Design haunts them.

Whatever we make or encounter–a thing, an arrangement of things, a procedure to arrange such things–is haunted by design. Even if design is not there, it is already there. Thus, the ontological status of design is a ghostly one. But design is a peculiar ghost, one that craves the tangible world of the living. Design is like Slimer, the gluttonous ghost from Ghostbusters: a specter that enjoys ingurgitating as much food as it can.

Slimer’s interactions with the material world are not seamless: they leave slime wherever they go. We can allegorically interpret such gelatinous secretion as design’s ability to reconceptualize things within its mode of comprehension: suddenly, a pebble starts having a form and a function, it gets liable to a process of improvement, a process that is itself subject to a method. What happened? Design has digested the thing: the pebble is now an artifact, a designed object. Design’s metabolism has left its muculent mark and spurred out what it couldn’t process, namely, the thing’s symbolic and ritual aura, its culture; substituted by design culture, with its own equalizing symbols and rituals. The thing is apparently the same, but it is in fact completely different.

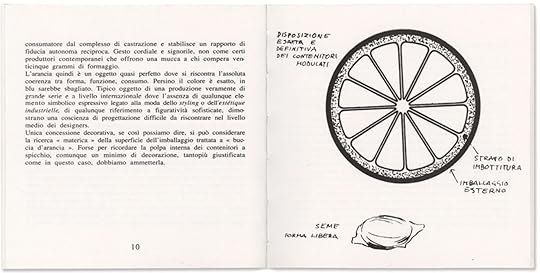

In 1963, Italian design polymath Bruno Munari amused himself by describing an orange, peas and a rose as industrial objects. Whereas the orange is “an almost perfect object”, the rose is deemed completely useless and complicated. Munari’s innocent divertissement, a sort of lesson in design thinking and perhaps a subtle critique of mass production, exemplifies the actual way in which design comes to reinterpret and thus change reality. Once such reinterpretation has happened it is very hard to think reality otherwise, beyond functionality and efficiency.2

According to design curator Paola Antonelli, designers are “respectful, curious, generous, and hungry for other fields’ bodies of knowledge and expertise, designers invade without colonizing. Who can we trust more? They should run the world.”3 Ruha Benjamin might disagree. Asked, during a workshop, to offer a definition of design, the sociologist suggested that “design is a colonizing project”. By that she meant that design is used to describe everything.4 Description is indeed the form that design’s slimy digestion takes.

As Paul Rodgers and Craig Bremner denounce, “design is neither a product nor a service. Design occurs in relationship to everyone and everything – it describes and shapes relationships.”5 Design proceeds through formalization. Focusing on one of today’s most successful design currents, design thinking, Benjamin points out its capacity to encapsulate any form of activity, from the organization of a protests to the user journey of a banking app. The problem is that design thinking is forgetful, not unlike design in general: it neglects histories.6 Again Benjamin:

If one needs to “subvert” design, this implies that a dominant framework of design reigns–and I think one of the reasons why it reigns is that it has managed to fold any and everything under its agile wings.

According to the US scholar, there are risks associated with design thinking, an “umbrella philosophy” that diminishes broader forms of human activity, erasing the genealogies from which they emerged in the first place, canceling what Ezio Manzini calls tradition.7 It’s a matter of hegemony: “Whether design-speak sets out to colonize human activity, it is enacting a monopoly over creative thought and praxis.” Benjamin’s concerns are specifically related to racial issues. From this vantage point she is able to see the way in which design depletes empowerment: “Maybe what we must demand is not liberatory designs but just plain old liberation. Too retro, perhaps?”

A sense of disillusion partly derives from the realization that design can be, like money, a general equivalent: something that severs the links between things and thus estranges them. It can devour contexts. Practitioners suspect that the umbrella is too small, that design is lacking the conceptual and practical means of encompassing human activity, and that by attempting to do so it is actually making tabula rasa.8 Design might be the last successful avant-garde: a deliberate repudiation of histories. Designers who come to terms with such awareness logically develop an impostor syndrome, an urge to resist design assimilation. This is probably a concause of many personal exoduses, dreamed or practiced: ex-designers decide to engage with the fullness of a certain human activity within its specific and historically-rich domain: farming, writing, cooking… all activities that resist the reduction to “rural hacking”, “content design”, or “food design”. More rarely, however, the act of design description provides an enrichment: the selectivity of design allows for the inclusion of forgotten voices, for the lighthearted reshuffling of austere practices, for a novel bridging of contexts. In these rare cases, design “ignorance” truly becomes its bliss. At worst, design flattens a multiplicity of worlds into a one-dimensional, aseptic one, at best it nurtures them.9

Presumably, this industrialized mindset started to emerge in the West in the 16th century, with the appearance of the first mechanically-reproduced books. ︎Peas are described as “food pills of various diameters, packing in double valve cases, very elegant in form, color, material, semi-transparent and easy to open”. Munari, Bruno. 2010. Good design. Mantova: Corraini.

︎Peas are described as “food pills of various diameters, packing in double valve cases, very elegant in form, color, material, semi-transparent and easy to open”. Munari, Bruno. 2010. Good design. Mantova: Corraini. ︎Paola Antonelli “Foreword”. In Midal, Alexandra, Design by Accident: For a New History of Design. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

︎Paola Antonelli “Foreword”. In Midal, Alexandra, Design by Accident: For a New History of Design. Berlin: Sternberg Press. ︎Benjamin, Ruha. 2019. Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. Medford, MA: Polity.

︎Benjamin, Ruha. 2019. Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. Medford, MA: Polity. ︎Rodgers, Paul A., and Craig Bremner. 2018. “The Design of Nothing: A Working Philosophy.” In Advancements in the Philosophy of Design, edited by Pieter E. Vermaas and Stéphane Vial, 549–64. Design Research Foundations. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-73302-9_25.

︎Rodgers, Paul A., and Craig Bremner. 2018. “The Design of Nothing: A Working Philosophy.” In Advancements in the Philosophy of Design, edited by Pieter E. Vermaas and Stéphane Vial, 549–64. Design Research Foundations. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-73302-9_25. ︎Susan Stewart puts it in more systematic terms: “the excision of history from design thinking isolates the understanding that informs the design act from any understanding of the temporal trajectories in which it participates.” Stewart, Susan, and Susan Stewart. 2020. “And So to Another Setting….” In Design and the Question of History, edited by Tony Fry, Clive Dilnot and Susan Stewart, 275–301. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781474245890.

︎Susan Stewart puts it in more systematic terms: “the excision of history from design thinking isolates the understanding that informs the design act from any understanding of the temporal trajectories in which it participates.” Stewart, Susan, and Susan Stewart. 2020. “And So to Another Setting….” In Design and the Question of History, edited by Tony Fry, Clive Dilnot and Susan Stewart, 275–301. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781474245890. ︎Manzini, Ezio. 2015. Design, When Everybody Designs: An Introduction to Design for Social Innovation. Translated by Rachel Coad. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

︎Manzini, Ezio. 2015. Design, When Everybody Designs: An Introduction to Design for Social Innovation. Translated by Rachel Coad. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. ︎If we are to consider “progressive” policy making as a form of design, we recognize a similar impetus for erasure, even in more explicit terms: “There is a sense in which rapid economic progress is impossible without painful adjustments. Ancient philosophies have to be scrapped; old social institutions have to disintegrate; bonds of caste, creed, and race have to burst; and large numbers of persons who cannot keep up with progress have to have their expectations of a comfortable life frustrated.” United Nations, Department of Social and Economic Affairs. 1951. “Measures for the Economic Development of Under-Developed Countries.” http://digitallibrary.un.org/record/708544.

︎If we are to consider “progressive” policy making as a form of design, we recognize a similar impetus for erasure, even in more explicit terms: “There is a sense in which rapid economic progress is impossible without painful adjustments. Ancient philosophies have to be scrapped; old social institutions have to disintegrate; bonds of caste, creed, and race have to burst; and large numbers of persons who cannot keep up with progress have to have their expectations of a comfortable life frustrated.” United Nations, Department of Social and Economic Affairs. 1951. “Measures for the Economic Development of Under-Developed Countries.” http://digitallibrary.un.org/record/708544. ︎The field of creative coding provides a good example of non-flattening design. Processing, one of the main programming languages deliberately conceived with artists and designers in mind, is part of a rich history of experiences where design bridges diverse fields of knowledge. Emerging from the MIT “lab” culture, in which Muriel Cooper, a graphic designer, had a leading role, Processing gave rise to a broad community of makers and thinkers who go beyond the drive towards efficiency of much computation culture. See Levin, Golan, and Tega Brain. 2021. Code As Creative Medium: A Handbook for Computational Art and Design. Cambridge, MA: The Mit Press.

︎The field of creative coding provides a good example of non-flattening design. Processing, one of the main programming languages deliberately conceived with artists and designers in mind, is part of a rich history of experiences where design bridges diverse fields of knowledge. Emerging from the MIT “lab” culture, in which Muriel Cooper, a graphic designer, had a leading role, Processing gave rise to a broad community of makers and thinkers who go beyond the drive towards efficiency of much computation culture. See Levin, Golan, and Tega Brain. 2021. Code As Creative Medium: A Handbook for Computational Art and Design. Cambridge, MA: The Mit Press. ︎

︎

March 28, 2021

Design Panism: A Timeline

1962

“Every human being is a designer. Many also earn their living by design – in every field that warrants pause, and careful consideration, between the conceiving of an action and a fashioning of the means to carry it out, and an estimation of its effects.” – Norman Potter

“Everyone is a designer, says Author Grillo in What is Design? Design is not the product of an intelligentsia.” – The Architectural Forum

1971

“All men are designers. All that we do, almost all the time, is design, for design is basic to all human activity.” – Victor Papanek

“Many books on industrial design suggest that design began when man began making tools. While the difference between Australopithecus africanus and the modern designer may not be as great as one might think or hope, the idea of equating man the toolmaker with the start of the profession is just an attempt to gain status for the profession by evoking a specious historical precedent. ‘In the beginning was Design,’ obviously, but not industrial design.” – Victor Papanek

1994

“Contra the widely promoted belief that design is something all human beings do and have done throughout history, but now must do more consciously and thoroughly than ever before, design is something that has had a history. Its beginnings can be traced to the rise of modernity, and it will almost certainly come to an end with the modern project. Indeed, we have an obligation not so much to promote designing as to learn to live without it, to resist its seductions, and to turn away from its pervasive and corrupting influence.” – Ivan Illich & Carl Mitcham

“We are all designers. Designing is integral to every intentional action we take.” – Tony Fry

1999

“There is a risk of falling into the trap of vague generalizations like ‘everything is design.’ Not everything is design, and not everyone is a designer […] Every one can become a designer in his special field, but the field that is the object of design activity always has to be identified […] The inherent components of design are not solely concerned with material products, they also cover services. Design is a basic activity whose capillary ramifications penetrate every human activity. No occupation or profession can claim a monopoly on it.” – Guy Bonsiepe

2003

“We are all designers. We manipulate the environment, the better to serve our needs. We select what items to own, which to have around us. We build, buy, arrange, and restructure: all this is a form of design.” – Don Norman

2004

“Design has emerged as one of the world’s most powerful forces. I has placed us at the beginning of a new, unprecedented period of human possibility, where all economies and ecologies are becoming global, relational, and interconnected.” – Bruce Mau, 2004

2007

“That design is not only an activity that trendy metropolitan design ‘creatives’ engage in: it’s a universal human life skill, a way of ordering, interpreting and enhancing our artefacts, images and surroundings, in which all of us should have a stake.” – Rick Poynor

2000

“Everyone is a designer!” Mieke Gerritzen and Geert Lovink

2010

“Looking back at the first edition of Everyone Is a Designer in 2000, when we proposed the idea of democratization of design, a decade later this programmatic statement has become reality.” Mieke Gerritzen and Geert Lovink

2015

“We are a designing species” – Victor Margolin

“In a world in rapid and profound transformation, we are all designers. Here, ‘all’ obviously includes all of us, individuals but also organizations, businesses, public entities, voluntary associations, and cities, regions, and states. In short, the ‘all’ we are talking about includes every subject, whether individual or collective, who in a world in transformation must determine their own identity and their own life project.” – Ezio Manzini

2016

“Design has gone viral. The word design is everywhere. It pops up in every situation. It knows no limit.” – Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley

2019

“If one needs to ‘subvert’ design, this implies that a dominant framework of design reigns–and I think one of the reasons why it reigns is that it has managed to fold any and everything under its agile wings.” – Ruha Benjamin

2021

“Luckily, design is something anyone in any discipline already knows how to do.” – Keller Easterling

February 16, 2021

The User Condition is out!

I’m glad to announce that I’ve just published The User Condition, a micro-interactive essay on computer agency and behavior. The essay concludes the blog post series on this subject.

December 7, 2020

No Problem: Design School as Promise

@neuroticarsehole, 2020.

GRAPHIC DESIGN IS SHIT CODING IS SHIT ALL I WANT IS REVENGE

– Sticker found in Berlin

The Promise

A promise is something that is put forward. It involves intent and expectation. It is a performative speech act: an utterance that, hopefully, does what it says. A promise is fulfilled when an intended future, now become past, finally aligns with the present. That’s when the speech act meets its condition of felicity.

What kind of promise (from now on simply “the Promise”) does design education involve? Does that relate to the present of education or to the future of work? What are the forces that shape it? How is it fulfilled and by whom? Who has the authority to sanction its fulfillment? Let us consider educational promises in general. First, they are not unilateral but reciprocal. It is not just the promisor, namely the school organization, in cooperation with or in opposition to the market and society, that is supposed to fulfill it (“We’ll give you knowledge, skills and a space to develop them”), but the individual promisee as well, the student, as they guarantee effort and participation (“I’ll make it worthwhile”).

Things get easily complicated because the Promise is not unambiguously formulated—there is no clear contract—and yet it looms over the promisee, functioning both as encouragement and threat. It can be rooted in notions like success, career, self-realization, ambition, autonomy… But, it can also aim at redefining them. It is affected by geography, class, race and gender. It comes in multiple shapes and forms and yet it can be understood as a whole. Does the Promise resemble a vow, an oath, a resolution, a mission? Is it as nebulous and frail as the American dream? In the design field things get even more complicated, as the field itself is in perennial reconfiguration: it experiences a constant identity crisis, some might say, fueling the personal identity crisis of practitioners.

To focus on the Promise means bridging preexisting societal conditions—such as employability, welfare, housing availability, discrimination, mobility, privilege—with socialized professional and personal aspirations—lifestyle, institutional roles, legacies of crafts, research trends, urgent matters, subcultures, notions of virtuosity… In other words, the Promise is built on some premises, at once materialistic and idealistic. When there is no full alignment between a promise and its premises, the promisee feels like they are compromising. From this a question arises: who is defaulting when the Promise is not fulfilled? And what can be claimed as compensation?

Recognizing the Promise means foregrounding intimate confessions, atmospheric peer pressures, individual anguishes, tacit dissatisfactions, concrete limitations, but also creating hacks, finding new paths, imagining different ways of living and working. It means reflecting on the design field’s linguistic tics and automatisms (such as working “at the intersection of”) in order to forge new vocabularies and approaches. It means designing new alignments of personal goals, collective aspirations and societal conditions.

Imagination

The first chapter of C. Wright Mills’ 1959 book The Sociological Imagination is entitled “The Promise”. This chapter is not, as I suspected, about generic expectations, such as having a house, finding a job or building a career. What Mills talks about is “the promise of social science”, ensured by a fundamental skill that the social scientist should muster.

Such skill is the sociological imagination. It is about connecting the personal and the societal, what Mills calls “the interplay of man and society, of biography and history, of self and world.” It consists in understanding personal troubles in the light of structural issues. A problem, for Mills, is an adequate formulation of these two scales. Here’s how he discusses it:

The sociological imagination enables its possessor to understand the larger historical scene in terms of its meaning for the inner life and the external career of a variety of individuals. It enables him to take into account how individuals, in the welter of their daily experience, often become falsely conscious of their social positions. Within that welter, the framework of modern society is sought, and within that framework the psychologies of a variety of men and women are formulated. By such means the personal uneasiness of individuals is focused upon explicit troubles and the indifference of publics is transformed into involvement with public issues. The first fruit of this imagination—and the first lesson of the social science that embodies it—is the idea that the individual can understand his own experience and gauge his own fate only by locating himself within his period, that he can know his own chances in life only by becoming aware of those of all individuals in his circumstances. In many ways it is a terrible lesson; in many ways a magnificent one.

As we see, situatedness is crucial to the understanding of how certain values might be cherished or threatened and how we react to such encouragements or threats. Mills provides a spectrum of reactions: well-being, indifference, anxiety and panic. These collective reactions are what he calls trends. What we are attempting here, keeping in mind Mills’ terribly magnificent lesson, is to reflexively turn the lens of sociological imagination to the milieu of (graphic) design, by looking at the implicit promises of design education. For a start, we can simply paraphrase some of Mills’ questions:

What varieties of [practitioners] now prevail in this field and in this period? And what varieties are coming to prevail? In what ways are they selected and formed, liberated and repressed, made sensitive and blunted?

The School

To be sure, the design field is vast and diverse, and so are design schools. What I want to focus on here is the kind of design school that isn’t uncomfortable with being associated with art: by indicating the fruitful relationships between the fields and their historical entanglement (think of the tradition of applied arts), I am interested more in the design schools that belong to the art academy than in those that are associated with architectural and engineering departments. This doesn’t fully solve our framing problem, though. So, my strategy will be to consider not a singular institution, and not even a series of them. Instead, I will focus on the School. The School is an “ideal type”, a useful fiction that, for the sake of the argument, combines, isolates (and maybe exaggerates) traits of the actual institutions I observed by means of direct involvement or distant scrutiny. Whereas the Promise is real, although vague, the School is unreal and yet derived from actual cases.

These cases, which are mostly concentrated in the urban nerve centers of the Netherlands (as well as being linked with the UK and the United States) are definitely a minority and don’t represent design education at large. However, they perceive themselves, and are often perceived, as a sort of avant-garde. Embodying newness, the School suggests directions to other organizations, both educational and professional. The School, supported by a generous system of public funds, can legitimately consider itself a site of reflection, cultural production and renovation. Admittedly, its novel culture is not passively accepted by the field at large, instead it is often confuted, adversed, or simply ignored. And yet, this culture influences the field. Whereas the School has the means to make a cultural idea visible to the field, it is not hegemonic and doesn’t want to be, at least ostensibly. The School doesn’t say “design should be this or that”, but it presents itself as the locus of doubt and experimentation. Certain ideas grown within the School will leak out in the field at large, through the practices of its alumni, through final shows, through textual production and debates later hopefully cemented into design history. But also through the mockery, skepticism and disdain of its detractors. In a 2011 essay, Rob Giampietro pointed out that the culture of design was becoming increasingly like the schools’ culture. The School is the laboratory where this very equivalence is produced. So, reverting the postulate, talking of the School means talking of the culture of design.

Biography

In the same essay, Giampietro wonders how the attitude of designers is formed. This question was triggered by something that he noticed in the context of design schools: an emphasis on biography and a heightened sense of self-awareness. The author points out that this biographical focus is not the result of a narcissistic leniency but it can be interpreted as one of the main burdens of the modern subject. As sociologist Ulrich Beck maintained, “people are condemned to individualization”.

Being proudly international, the School values and encourages biographical expression as an interface to cultural difference, a badge of honor given its multicultural ethos. However, the risk is that a biography perceived as uncommon—in geographical, class or bodily terms—is exoticized and therefore “othered”. Here, the unfamiliar biography is made valuable (“one’s roots”) not for its intrinsic value as the story of a life, but because of its scarcity. A work that mobilizes an unfamiliar life story is framed as a cultural statement while one that is rooted in a relatively usual biography might be deemed mere egotistic indulgence. Not everyone’s “becoming who they are” is validated in the same way. In both cases, the School is in trouble because it struggles to discern the biographical from the personal, what it relates to one’s place in society from what is a feature of individual character, what is debatable from what should be unquestionable.

A keyword that points to such tensions is position. The most frequent question one hears in the School is “how do you position yourself?” The question is of course of a maieutic kind: it is meant to help students situate themselves in the issue they are investigating or, more rarely, in the problem they’re trying to solve (more on that later). The question works as an injunction because it forces the student to produce, or at least reflect on, a self-image. The position can be the one of designer as mediator, as problem-solver, as activist, etc. Or more broadly, for instance, as male, as Western, as able-bodied. Positional complexities are now at the heart of the field’s identity crisis. As the School as a whole rarely has the conceptual tools to address them, this identity crisis (that has always characterized the field and now just feels more apparent) is shared with, if not offloaded to, the student-practitioner.

What’s the School’s responsibility here? Will it still be able to reproduce itself as a progressive institution? How can it facilitate the generative crisis of the field without turning it into the identity crisis of individual students? Positional maieutics is a valid and useful means, but the dilemmas and wicked problems that it engenders should not be merely outsourced to individual students. Furthermore, the School should use those dilemmas neither as formal nor informal evaluation criteria, such as a grade or the conferral of trust.

Autonomy

The very fact that one can reflect and partly shape their position indicates that the Promise is one of autonomy and self-discovery. However, this process is rarely tied to material constraints. When urging students to become who they are, the School developed only a partial alertness and sensitivity: it is rarely concerned with class, census or wealth. Talk on professional exploitation and self-exploitation, increasingly high fees, little pay, unemployment, unfair working conditions, uneven funding possibilities, expiring visas, etc… in one word, precarity, is still infrequent. As it is infrequent to point the finger at the most obvious power disbalance within educational institutions: on the one hand, the powerful managerial class (the stable organogram) and on the other, the fragile teaching staff, whose members are occasional and redundant. Instead, successful stories imbued with survivorship bias are foregrounded.

To avoid misunderstandings, let me say this loud and clear: all the dimensions of inequality are equally important. Not just important, they’re real and inextricably linked. A School that is explicity anti-racist and non-patriarchal is also, by default, against precarity. If that thing we call progress actually exists, this is where we see it.

An emphasis on precarity is much needed as it counterbalances the myth of life and career self-determination that can be fuelled by a simplistic idea of autonomy and self-direction. An emphasis on inequality would foreground what is statistically hard to achieve and what aspects of practice are strictly dependent on local possibilities. In other words, to what extent society determines biography.

I suspect that a miopia towards professional limitations results from design and designers’ protagonism (more rarely, from a solid and remunerative career). What matters is the mark that the designer leaves on the world, not the scar that the world leaves on the designer. Professional disadvantage might sound gloomy, depressing, almost a petty subject. A workshop on precarity? Not fun. Surely, the School doesn’t want to sadden its students. And yet, workshops on entrepreneurship abound. Is there a way to lead their interest to these topics without curbing their enthusiasm? This is the dilemma that the School, usually proud of its criticality, must address if it wants to be considered fully critical.

Practice

The promise of autonomy implies the principle of self-direction: within the School, the student is given a space and time to direct their own work. A practice is the outcome of self-direction. What do we mean by that? “Practice” is a term used mainly in the arts to define an artist’s poetics. It involves the artist’s concerns, their method, their medium and even their theoretical and ethical ground. Through the decades, design has been considered a style, a craft, a method, and later a thinking approach. Now, with the notion of practice, we observe an extension of the meta-understanding of the designer’s activity. What does this shift mean? Borrowing from programming, one could say that each “constant” of the discipline (methods, techniques, media and products, literacy, topics, ethical issues) is turned into a variable. Unavoidably, a degree of specificity is lost as the student is encouraged to tweak all these variables. But if none of these is shared among peers, how can we call this a field? Again, the liberating potential of tweaking the very terms of one’s work might also lead to isolation and individualization. The School, partially aware of this, compensates the atomizing drive with participatory and collaborative modes of interaction.

I can’t refrain from wondering whether the practice model—with its consonance to the profoundly isolating subject formation of the art world, which rarely offers more than a faint sense of belonging—is a weak form of professional, and therefore social, reproduction. Maybe, the traditional medium-based or problem-based orientation was stronger for the simple fact that it shared at least some fixed variables. The point, however, is not to choose one model over the other, but to raise a specific concern: what effects does the “practice of practices” have on identification? Is the School partially responsible for the disintegrating sense of belonging and tangible social isolation that many practitioners, often self-defined as “outsiders”, feel? By offering an abstract promise of autonomy, is the School uncritically abdicating its role to nurture the field?

Problem

Variable manipulation is so radical that one variable might take the place of the other. As Giampietro pointed out, in certain design contexts “research […] is not only an analytic method but also a cultural product unto itself”. The School presents research as the very artifact that is offered to the public. However, it rarely clarifies what research actually means, who this public is and how it is going to consume such research. The specter of self-referentiality manifests: will this research be read and seen by designers only? The emancipating image of a practice “without reliance on commissions” and with no problem to solve might look like a shout into the void, as the lack of commission might coincide with the absence of an audience. The sites in which research as a cultural product is consumed are mostly educational in ambition: the gallery, the museum, the school itself. It seems that the School is trapped in its own pedagogical afflatus, and extends the student paradigm to the public as a whole, a public that is often indifferent. Instead of the socially-oriented “double commission” (the client and the public), we end up with “zero commission”: no public and no client.

Traditionally, problem solving has been a defining aspect of the design field. The designer used to solve problems, both big and small. Perhaps pushed by the tedium and frustrations of client-based work and the scarcity of grand-scale problem-solving positions available, various currents have challenged this approach. As a consequence the School has developed an allergy for that word: problem-solving feels petty and naive, undignified. Designers are meant not to solve but to frame problems, to be, in other words, cultural agitators, people who raise awareness, influencers. Design’s main category once was “the problem to solve”, now it’s “the problematic issue to address”. Is this an attempt to question the way in which problems are constructed by the larger system or is it a form of disciplinary surrender?

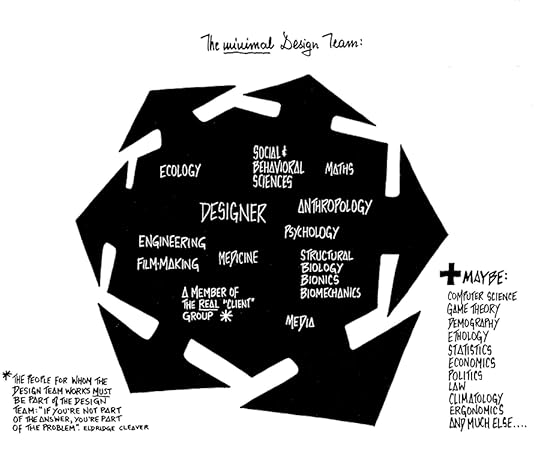

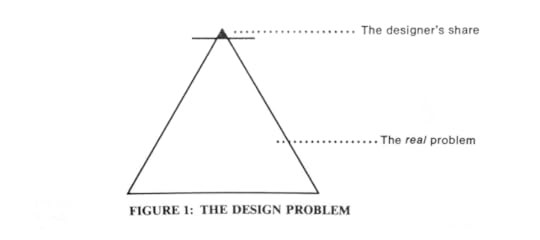

Victor Papanek’s Work Chart for Designers, 1975 (detail).

Take Victor Papanek’s complex diagrams of interrelations for an “integrated design team”: one feels dizzy just by looking at them. The reason why these diagrams feel overwhelming is that they ask for a configuration that hardly exists. Papanek provocatorely asserted that the minimal design team would include social and behavioral sciences, maths, biology, maybe even computer science (and also, commendably, the final users of the design). Outside of corporations and big studios, such a design team is mostly utopian. But the School, despite training designers who will frequently develop small-scale practices, operates according to this pseudo-fiction. As a result, the student is forced to become their own minimal design team, timidly approaching all the disciplines involved. Since getting in touch with an expert is apparently effortless (“just drop her an email”), interviews and surveys (when and if the expert replies) become the interface with other areas of knowledge. Even before having a job, the student becomes “hyperemployed”.

The notion of scale is key. Papanek’s not-so-minimal team is mainly economically viable when it comes to big-scale products and services, but the School’s non-commercial autonomous practitioners rarely deal with them. Here’s a depressing truth: for all the talk about design’s role in society, the big-scale impact on the world left by designers as a demographic cohort lies less in the design work they do than in the consumer choices they make. The laptop they buy counts more than the poster they design with it.

Victor Papanek’s Design Problem, 1975.

Let’s now consider another Papanek’s diagram, which states that the designer’s share of a certain problem is rather small. In the interplay of these two diagrams lies the cognitive dissonance present in the School: the student is encouraged to explore the whole pyramid while being aware that they will mostly be confined to its tip or, more realistically, to its basis. The scope may feel exciting and liberating at first but also turn tiring and disorienting.

Here, a necessary distinction must be made between an educational context and the outside world. The School offers a safe space for systemic thinking, an invaluable exercise from which the student undoubtedly benefits. But there is also a more worrisome consequence. It takes the shape of an anti-solutionist nihilism: problems are too big, multilayered and wicked to even attempt to solve them, what we can offer is interpretation by means of critique, Frankfurt School-style. A critique that—it is painful for me to say this—is sometimes mired in conformism and superficiality. A critique that seems to take a morbid pleasure in portraying its object. A critique that, as said before, rarely reaches a public larger than the designer’s crowd. We should ask ourselves: what degree of agency do these modes of inquiry provide? Where are they supposed to land? Are there environments which are receptive to such approaches? If so, how can we nurture them? And are we able to identify locally-bound situated problems that speak to larger systemic issues?

The modernist tradition of design was tied to a god-view perspective. The designer would observe the world from above. Now, the grand metascale of the problems tackled by the School perversely renews such perspective, but the sight couldn’t be more different. Modernist universal values turn into the School’s “reductio ad absolutum”: designers are now urged to engage directly with the megamachine, the hyperobject, the Stack… with Capital itself. This novel synoptic view resists synopsis: it doesn’t show, like in the past, the illusion of an orderly terrain, but a stormy sky heaving on a frightened practitioner. This scenario might have contributed to the emergence of the counter-currents of design intimism (“the world is scary: I focus on myself”) and even design revanchism, the latter mostly performed on Twitter (“design is useless: I want revenge”).

The stormy sky is not just theoretical dramatization. Reality is indeed complex and multifaceted. In one word, scary. The School shouldn’t deny this but it must be able to provide guidance. It should attempt to bridge the scales, showing how the macro is in the micro. It should resist the grandiose General Theory, but also prevent a defeating relativism. The role of the School is to make big things approachable and small-scale gestures valued.

Expertise

“‘In the beginning was Design’, obviously, but not industrial design.” wrote Papanek. Designers argue that everything can be design, only then to reclaim their monopoly on it. Through the decades, this generalization took another form: design became understood as a sort of glue between disciplines, a bit like cybernetics. As a result, designers started to see themselves as mediators facilitators interpreters… What about the vocabularies needed to fulfill such roles? I don’t even bother, the list would be too long and controversial. What I want to point out here is a double movement: on the one hand, designers try to become polyglots to communicate with various experts; on the other, they relinquish an intimate relationship with specific crafts. This is not just the outcome of the field’s volition but also an aftereffect of the digital banalization of competences, e.g. typographic knowledge being crystallized in software.

Deskilling, which is another name for superficial overskilling (knowing a little bit of everything), goes hand in hand with softskilling. The designer is not anymore an expert of craft, process and method, but an expert of mediation, articulation and framing. Their environment is the meeting room and the conference panel more than the laboratory or the studio. Their main medium: the slide deck or the video essay. Here, we find a parallel with the tertiarization of work where soft skills, both social and managerial, are trumping the hard skills of craft and making (in this respect, the overuse of the term “empathy” in service design comes to mind). At best, this can be seen as an intellectually rich interdisciplinary frontier; at worst, this might appear as a cerebral post-medium, post-craft territory. All of this takes place with the backdrop of a more general crisis of competence: experts aren’t trusted anymore. Papanek called for an anti-specialized design education. In his view, the problem was “too much design” in the curricula. Four decades later, the School has indeed become a school of generalists, but I’m afraid he would consider much of what is produced there “‘self-indulgent’ anti-design”.

Within this epochal change, the School rightly encourages the student to exercise care and considerateness, as well as to organize and facilitate the work and the hard skills of others, to become a sort of impresario who holds a vision. Next to this explicit level of valorization, there is also an implicit one where other soft skills matter: enthusiasm, proactivity, confidence, resilience, flexibility. This begs the question of how much the School is itself considerate toward characters that do not fully adhere to the attitudinal norm it sets.

A student meme reads: “I went to art school and all I got was this fucking attitude”. I find the attitudinal emphasis at the expense of craft a bit disconcerting. I’m afraid that the soft-skill, post-craft ideology of the School might be rooted in entrepreneurship, or even worse, on outsourcing. In fact, it is not infrequent for a student to use online marketplaces like Fiverr.com to complete their project. The general devaluation of skill-specificity is also worrisome because, in a society that cherishes work above all, craft is often one of the few stable forms of identity making: the mastery of a craft goes way beyond a professional title. “A good job well done” can be an island of personal stability within an ocean of impostor syndrome and self-doubt. Furthemore, craft goes against radical, make-believe horizontalism by showing the positive side of hierarchy: a workshop master-apprentice relationship is not in itself an exploitative, abusing one.

Politics

Once, a semiotician told me: “design schools train students to become whatever they want, except designers.” Given what can be considered as an expansion (or even a dilution) of the design field, the School can no longer be seen mainly as a site of professional reproduction but rather as a forge of attitude. The School allows the student to materialize their cultural and subcultural interests, their hobbies, their nerdiness. Part of the Promise lies is the opportunity to transform all these identity features into a portfolio of projects. To turn cultural consumption into cultural production, cultural capital into economic capital. There’s nothing wrong with that, but it’s a development worthy of reflection. Shall we call it the adolescence turn? After all, the design field is kind of young. Adolescence is self-referential by definition: it is more about the self than the world. And anyone who used to wear a RATM shirt during their teenage years, knows that politics is one of the various forms of identity building.

The School actively encourages this form of identification: being “political” is a plus. There is, however, an idea of politics which I find slightly reductive: politics as what the work says more than what it does. The statement, the manifesto, the invective are more positively scrutinized than the inner logic or the social relationality of a work. Politics as a badge rather than a process, with the further risk of turning it into a fetish, a formal requirement, a norm. The design field at large is still imbued with ornamental politics: the radical slogan, the activist posture, the glorious declaration are adopted as decorations of purely autonomous practices, that is, cut off from the murky waters of micro and macro politics. Often—not always—the political is reduced to the equivalent of Che Guevara’s pin on an Invicta backpack.

In 1998 Mister Keedy wrote on the pages of Emigre: “Today’s young designers don’t worry about selling out, or having to work for ‘the man,’ a conceit almost no one can afford anymore. Now everyone wants to be ‘the man.’ What is left of an avant-garde in graphic design isn’t about resistance, cultural critique, or experimenting with meaning. Now the avant-garde only consists of technological mastery: who is using the coolest bit of code or getting the most out of their HTML this week.” In the context of the School, quite the opposite is true: explicit cultural critique comes at the expense of “mastery”, which is deemed as narrow-mindedness. I’m not saying that the School should reject politics and pretend to be neutral, because we know that there is no such thing as political neutrality. What I’m saying is that political orientations shouldn’t become passe-partout. The student should not be pushed to inject politics for politics’ sake into the work. And politics should be understood broadly: a political work, understood as a work with explicit politics, is not superior to a “formal” work, which implicitly enacts its politics.

Informality

The School resists formal structures, even conspires against them. Within its environment, a suspension of disbelief towards formality is produced: the School is amnesiac to the very fact that it is indeed a formal institution. Somehow, it has digested decades of self-organized educational initiatives. The School conceives itself as an anti-school, a parallel school, an unlearning and a relearning site. This self-image is part of the allure it emanates and the spirit it projects. Informality doesn’t just come natural but is the product of a proteiform intentionality, corroborated by a broader distrust of bureaucratic structures. But this informal turn goes hand in hand with an inflation of managerialism, which is a type of bureaucracy that is able to mobilize informality. Being put to work, informality becomes the School’s new formalism.

Designer and writer Jacob Lindgren recently published a piece in which he criticizes the rigid structure of current graphic design schools. “We need the common, the occupied, the appropriated, and the lesser governed spaces”, Lindgren writes, quoting “A Letter for the Academy” by Parallel School. This could have well been a statement issued by the School itself. Informality doesn’t like numbers, it prefers words—only certain words actually, and “student” is not among them. Instead of grades, it generates a multiplication of feedback forms and conversations. Despite wanting to be holistic and horizontal, informality does not erase the intrinsic power imbalance between teachers and students (and even more, between teachers and management). New forms of validation, no less messy and abstract and obscure than grades emerge: individualized collaboration opportunities, good words, friendships. Validation becomes interpersonal rather than institutional. Charm acquires prominence. Emotion work becomes at least as important as productive labor. Governing forces feel too human to bear.

Validation also affects the teaching staff, partially fueling the Promise. The School’s teacher (often called “coach” or “mentor”) is generally a practitioner as well: they’re able to make a living out of their practice, or at least so it appears. While teaching, they also substantiate their research. Sometimes, it is the very income derived from teaching that makes their professional persona possible and real. As students logically aspire to build such a professional persona for themselves, the School, like a ouroboros, offers the Promise of itself. To what extent is this form of validation in line with that of the industry and society at large? To avoid that “no grades” turns into “no jobs”, the continuous effort to bridge validation systems, internal and external, implicit and explicit, should be one of the School’s main concerns.

This is not to say that the student is uninfluential or uncritical. It might well be that a generation of students develops a wariness towards the kind of persona that the School encourages. There is a metabolic relationship between the School and the student. The former exerts explicit or implicit power on the latter, while the latter influences and reshapes the former, bringing new conceptual energy to it. If the opaqueness of validation is informality’s negative side, an ease of reconfiguration is its positive side.

Future

To what extent is the School actually attentive to the future? The temporally and geographically distant, and therefore safe, canned futures of speculation are favored over the tedious and mundane present-like pseudo-future of life-after-graduation. Again Papanek: “It is also in the interest of the Establishment to provide science-fiction routes of escape for the young, lest they become aware of the harshness of that which is real.” As this prospect is grim in the most unspectacular way (this is what makes it terrifying), the School recasts the Promise as something oriented to the present: a promise of space and time, protected from the idiotic frenzy of the work grind. In fact, several students arrive at the School after years of professional activity.

Present-orientedness makes sense: if the School is truly a site of cultural production, what it has to offer are mostly the relationships that take place within its shelter. Not cultural production, then, but the production of a culture. Some would call this “prefigurative politics”, a sort of controlled experiment that is meant to be later implemented on a larger societal scale. If this is the case, the issue of individual sustainability should be central. Exiting the sandbox, would the student fall into an abyss?

This is the humble urgency that even students themselves tend to postpone to the last months of education (if they are not preoccupied with things like visas), in favor of more epic and apparently noble urgencies dictated by the agenda of the museum-festival complex. One does not even have to wait for graduation to encounter the unfashionable urgency of circumstances. A proof being the crowdfunding campaigns to afford concluding one’s studies in cities with rocket-high rent and a housing crisis, or even beginning these studies in the first place! A new “design challenge” is getting traction: craft a GoFundMe to sustain your design studies in a fancy cultural hub.

The Field

To conclude, let’s to go back to Mills’ paraphrased question:

What varieties of [practitioners] now prevail in this field and in this period? And what varieties are coming to prevail? In what ways are they selected and formed, liberated and repressed, made sensitive and blunted?

In this text, I tried to problematize a series of developments of design education. I focused on my own niche context, but I suspect students and educators outside of it will recognize some of the issues I dealt with. Among them, the ascendance of a biographical style. I provided various interpretations for it: a way to stabilize oneself within increasing complexity and professional dilution, a problematic interface for cultural diversity, an intimist disengagement from the world, an identity-making process based on the mobilization of a certain cultural or subcultural capital, and finally, a form of self-indulgence.

It is risky for an educational organization to engage with biography, especially in a time when individualism is forced upon individuals. Not every facet of biography should be scrutinized by the School. And the ones that deserve attention, shouldn’t be personalized. To manage this complexity, the School should become able to navigate intimacy, privacy and confidentiality. Most of all, it should avoid flattening a life story into the project-practice surface for evaluation or promotional purposes.

The Promise has to do with the design of the self. Self-design can be umbilical, pathologically self-reflexive, asocial. It can be unsettled by an essence that is not there. It can obsessively measure itself with the ghost of identity. This is its fixed idea. It is not difficult then to understand the desperation of those students who come to school to engage with a system of thought, and instead find themselves placed in front of a mirror. Through self-design, biography relates to the notion of autonomy (shall we then, keeping in mind autofiction, speak of autodesign instead?). But autonomy can mean exile. Self-direction can lead to isolation. The variable-tweaking process that constitutes a design practice might resemble micro-targeting advertising: as specific as to address one person only. It might be that “at the intersection of” (an expression commonly found in designers’ bios) there is no one else other than you. Autonomy can adumbrate precarity and insidiously replicate the much despised design protagonism. In which case, that is not autonomy but wishful thinking. Fauxtonomy, if you will.

Modernist comfort might be gone for good, but postmodern disorientation is here to stay. Complexity looms over us. What are we to make of ourselves? Identity crisis is not just personal: it exists at many scales. The presentiment of mundane futurelessness is concealed by the glamour of Big Dystopia. Tempted by overskilling dilution and mesmerized by the multidisciplinarity frontier, avant-garde design education might be abdicating professional reproduction and solid identity-making. Instead, it might be disseminating existential self-doubt and confusion.

To avoid succumbing to the multilayered identity crises driven by fauxtonomy and futurelessness, it’s time to put self-design aside and rebuild the Field. The Field is the space inhabited by a series of connected communities of practice (where practice is not understood as in contemporary art, namely devoid of an authentic communal sense). The Field doesn’t shy away from problems. Instead, it constantly redefines its own set of issues and concerns: functional problems, ethical problems, problems of method, of access, of inclusion. The Field deals with complexity but doesn’t try to tackle it in its entirety. Through the specialized knowledge it produces and the situated activity it performs, it glances at complexity without being blinded by its frightening god-like appearance.

The Field is a political entity, but not because it regularly issues statements and manifestos (even though it might do that as well). The Field is political because it is busy with its own organizational politics, as well as the politics of the artifacts it designs and circulates. The Field is preoccupied with tangible, lower-case futures. The future rests in its surroundings, but also in the broader effects that interventions on these surroundings have. It is thus embedded in a gradient of scales.

The Field is not a scene: its main motor isn’t visibility. It might even unconsciously limit the exchange with the outside. But if it is too self-referential, that’s not the Field, it’s a club. The main interface with the outside and between its members is a physical space: the Field is aware of the insufficiency of online-only communication.

The Field is not a school: while learning takes place within it, scholastic hierarchies, both implicit and explicit, don’t apply there. This doesn’t mean that it rejects hierarchy completely: its structure is based on the healthy, reconfigurable hierarchies of apprenticeship, amateurship and curiosity.

The Field isn’t a school and the School isn’t the Field, but they benefit from each other (collaborations with local collectives, self-organised spaces, etc). What the School gains from the Field is a sense of specificity and purpose; what the Field gets from the School is financial resources and the possibility to open up to new publics. But the exchange is asymmetrical. The Field is in a less stable position: collectives come and go, and their sustainability is currently put to the test. The occasional workshop fee is not enough to maintain the Field alive. And yet, given its ambitions and limitations, the School is increasingly dependent on a lively Field. Without the energies of a surrounding Field, the School is doomed to become a managerial graveyard.

The Field is informal in nature, but it doesn’t fetishize informality: it resists character normativity and protects its people from hurtful behavior. The Field is attentive to its flows of social, cultural and economic capital: it is generous with quoting, crediting and remunerating; it doesn’t trust impresarios and creative directors; it rejects inner qualitative distinctions: all the work it needs is essential, interdependent work. Validation comes with effort, helpfulness and mutuality, more than with smartness, talent and bravado. The Field is not a guild: it’s not preoccupied with the protection of its trade. The Field believes in expertise, but it doesn’t worship experts.

The Field provides an activity-based sense of belonging and identity: people have roles and purposes, but these can be renegotiated. The Field understands biographical and cultural differences, but foregrounds them only when necessary. Within an instance of the Field, a practitioner can joyfully forget about themselves.

Acknowledgements

My gratitude goes to Manetta Berends, Sami Hammana, Geert Lovink and Gui Machiavelli for reading drafts of this text and giving precious feedback. I’m also thankful to Varia, which represents in many ways the community of practice I tend to idealize here. This work is the result of countless discussions, disagreements, misunderstanding with students and colleagues. I wish to thank them all. I do this anonymously as I don’t want the School to be understood as a school in particular: it is not. Each school exceeds the School because actual human relationships are ineluctably exceptional and unique.

October 5, 2020

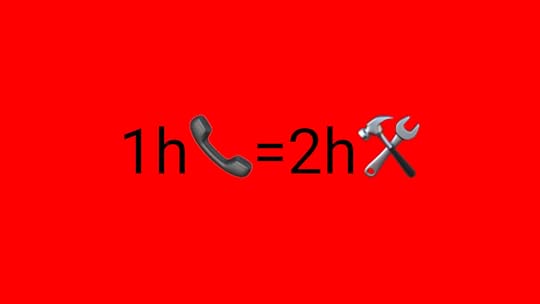

1h call = 2h work

These last few days, inspired by Geert Lovink’s upcoming essay on Zoom Fatigue, I’ve been thinking a lot about videoconferencing and telework. And then today I was asked to borrow a non-Linux machine to participate in a live talk because Teams’ “Live” function is not supported by the Linux version of the software. Lock-ins ahead. Luckily, the other speaker is also a Linux user so we didn’t have to feel weirdos… Anyway, everybody seems to agree: videoconferencing is exhausting. But how can one turn exhaustion into a political demand? My proposal is to consider videoconference work (Zoom, Teams, Skype) from the prism of recovery time, namely, the time needed to regain mental and bodily energies. My empirical assumption is that videoconference work (Zoom, Teams, Skype) requires twice as much of recovery time as the same activity performed in a physical setting or as regular, async digital communication (email, chat, etc.). And what is recovery time if not just another name for work? If that is the case, one can formulate a concise slogan reminiscent of the “8 hours labor, 8 hours recreation, 8 hours rest” one. Here’s some versions of it:

1h call = 2h work

1h