Silvio Lorusso's Blog, page 2

January 5, 2024

Midjourney as a Starbucks Barista

Working with Midjourney is like running into an overly proactive Starbucks barista. “I’d like a coffee.” And they bring you a Caramel Macchiato. “But I didn’t want caramel.” So they bring you an Espresso Macchiato. “I’m lactose intolerant.” A little impatient, they bring you a Coffee Americano. “But there’s too much coffee here.” Now visibly annoyed, they bring you a Sugar Cookie Almondmilk Latte. “Who asked you that?!” “That’ll be $14.99” and they go on misspelling your name on the cup.

November 19, 2023

OUT NOW: What Design Can’t Do

My new book What Design Can’t Do: Essays on Design and Disillusion, with Federico Antonini’s melancholic design, is finally out.

Get it from Set Margins’ website and soon from many great bookshops.

Thanks to all of you who pre-ordered it. It means a lot, and not just symbolically. Hang in there, your copy is on its way.

Abstract and Endorsements

Design is broken. Young and not-so-young designers are becoming increasingly aware of this. Many feel impotent: they were told they had the tools to make the world a better place, but instead the world takes its toll on them. Beyond a haze of hype and bold claims lies a barren land of self-doubt and impostor syndrome. Although these ‘feels’ might be the Millennial norm, design culture reinforces them. In conferences we learn that “with great power comes great responsibility” but, when it comes to real-life clients, all they ask is to “make the logo bigger.”

This book probes the disillusionment that permeates design. It tackles the deskilling effects provoked by digital semi-automation, the instances of ornamental politics fashioned to please the museum-educational complex, the nebulous promises of design schools. While reviving historical expressions of disenchantment, Silvio Lorusso examines present-day memes and social media rants. To depict this disheartening crisis, he crafts a new critical vocabulary for readers to build upon. What this exposé reveals is both worrying and refreshing: rather than producing a meaningful order, design might be just about inhabiting chaos.

What was once a promising field rooted in problem-solving has become a problem in itself. The skill set of designers appears shaky and insubstantial – their expertise is received with indifference, their know-how is trivialised by online services, their work is compromised by a series of unruly external factors. If you see yourself as a designer without qualities; if you feel cheated, disappointed or betrayed by design, this book is for you.

“Are you a bit depressed about design? This book might help you understand why. It may also make you laugh. With a lightness of touch, Silvio Lorusso provides an unflinching but well-reasoned discussion as to how design has become so ‘bigged up’ and what this actually means for its practitioners. After reading this book, design will never look the same to you.” – Guy Julier, author of Economies of Design

“What happens once design is a smokescreen and can no longer claim to be a blueprint for change? This is the question Silvio Lorusso puts on the table. How did form, no matter how cool and disruptive, become so futile and tired? Read this with caution: we can no longer design ourselves out of this painful realisation.” – Geert Lovink, author of Stuck on the Platform

“The disillusion of design is the disillusion of the world. This book is an essential read, not only for specialists. Because design affects us all, and because understanding where design fails helps us understand where design succeeds.” – Emanuele Quinz, author of Strange Design

“Italo-pessimist design critique at its best.” – Clara Balaguer, cultural worker and grey literature circulator

October 14, 2023

Appunti sparsi a proposito di immagini e intelligenza artificiale

Immagine non generata con l’IA bensì con il buon vecchio Content Aware Fill di Photoshop.

Le immagini generate con l’ausilio dell’intelligenza artificiale sono doppiamente retrospettive. In primo luogo in senso tecnico, in quanto costituite a partire da un dataset preesistente. In certa misura ciò vale per qualsiasi immagine, tuttavia i dataset sono caratterizzati da una soglia precisa: i materiali raccolti, ad esempio, si possono fermare al 2021. In secondo luogo, queste immagini sintetiche sono retrospettive in senso culturale: osservandole si ha già il presentimento che il trend visivo di oggi sarà obsoleto dopo il weekend. Da ciò derivano tutti i tentativi di collegare, serializzare, commentare, catalogare, musealizzare… insomma giustificare tali immagini. Tramite una canonizzazione fai-da-te si cerca di salvarle dall’abisso imminente.

Jean Baudrillard a proposito di Midjourney (1994): “L’arte diventa iconoclastica. L’iconoclastia moderna non consiste più nel distruggere le immagini, ma nel fabbricare immagini, una profusione di immagini in cui non c’è niente da vedere. Sono, letteralmente, immagini che non lasciano traccia. Prive di conseguenze estetiche, per essere esatti. Ma, dietro ognuna di esse, qualcosa è scomparso. Questo è il loro segreto, se mai ne hanno uno, e questo è il segreto della simulazione. Non solo all’orizzonte della simulazione il mondo reale è scomparso, ma il problema stesso della sua esistenza non ha più senso.”

Per liquidare l’ingenuo affidamento sulla Morte dell’autore è sufficiente precisare che quel saggio fu firmato nel 1967 con nome e cognome.

Tra gli effetti dell’uso corrente di intelligenze artificiali generative ce n’è uno che si può riassumere così: un’inversione del rapporto figura-didascalia. Ovvero, nel momento della pubblicazione (ed è qui che si dichiara puntualmente l’utilizzo dello strumento), non è il testo a “spiegare” o “raccontare” l’immagine, bensì è l’immagine generata a fare da supporto – di volta in volta – al prompt utilizzato, all’aneddoto casuale o alla tesi sui media. Non a caso sono moltissimi gli accademici che hanno abbracciato l’arte del prompting: il testo è e rimane la loro zona di comfort. L’immagine, invece, svolge un ruolo ancillare. Questo è il motivo per cui le immagini generate con l’IA e pubblicate sui social hanno sempre un po’ il sapore di segnaposto. Anche quando il testo in questione manca, se ne sente l’assenza: cosa avrà digitato l'”ingegnere dei prompt” (detta in italiano, questa formula suona ancora più ridicola) per generare tale figura?

Sostengono che l’idea di autore è “sovrastruttura borghese”, e poi nel loro lavoro, nelle loro idee e nelle loro pose indossano i panni autoriali più consueti e consunti, mentre noi sono anni che adottiamo il punto di vista tattico della produzione diffusa e anonima che foraggia la falsa coscienza di quegli autori che si vergognano di essere tali.

Dirò la mia sull’intelligenza artificiale a tempo debito, cioè a cose fatte, ovvero quando la singolarità sarà stata finalmente raggiunta e qualunque cosa io dica a quel punto non sarà meno inutile, anzi del tutto inutile e proprio per questo perfettamente consona, di quanto sarebbe dire la stessa cosa adesso.

September 11, 2023

What Design Can’t Do is in Pre-order

Almost there. My new book What Design Can’t Do will be out in late October with Set Margins’, but you can already pre-order it. Here is the cover, designed by Federico Antonini.

Design is broken. Young and not-so-young designers are becoming increasingly aware of this. Many feel impotent: they were told they had the tools to make the world a better place, but instead the world takes its toll on them. Beyond a haze of hype and bold claims lies a barren land of self-doubt and impostor syndrome. Although these ‘feels’ might be the Millennial norm, design culture reinforces them. In conferences we learn that “with great power comes great responsibility” but, when it comes to real-life clients, all they ask is to “make the logo bigger.”

This book probes the disillusionment that permeates design. It tackles the deskilling effects provoked by digital semi-automation, the instances of ornamental politics fashioned to please the museum-educational complex, the nebulous promises of design schools. While reviving historical expressions of disenchantment, Silvio Lorusso examines present-day memes and social media rants. To depict this disheartening crisis, he crafts a new critical vocabulary for readers to build upon. What this exposé reveals is both worrying and refreshing: rather than producing a meaningful order, design might be just about inhabiting chaos.

What was once a promising field rooted in problem-solving has become a problem in itself. The skill set of designers appears shaky and insubstantial – their expertise is received with indifference, their know-how is trivialised by online services, their work is compromised by a series of unruly external factors. If you see yourself as a designer without qualities; if you feel cheated, disappointed or betrayed by design, this book is for you.

“What happens once design is a smokescreen and can no longer claim to be a blueprint for change? This is the question Silvio Lorusso puts on the table. How did form, no matter how cool and disruptive, become so futile and tired? Read this with caution: we can no longer design ourselves out of this painful realisation.”

– Geert Lovink, author of Stuck on the Platform

June 22, 2023

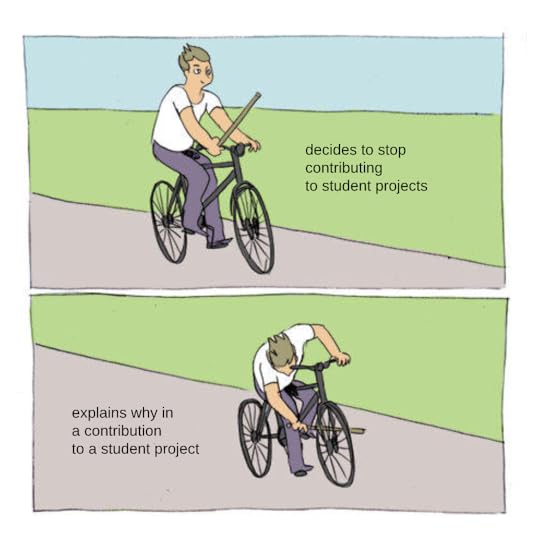

Why I (Almost) Stopped Contributing to Student Projects

Every year, one or two months before graduation time, I receive invitations from students of various institutions to contribute to their final project with an interview, a podcast, a short text, a talk, etc. Some of these requests derive from projects that are genuinely interesting and related to what I do, while some other requests feel, to be frank, a shot in the dark. But that’s not the point.

The point is that some time ago I stopped accepting most of these invitations directly. The reason is not that I find student projects unworthy of my attention. On the very contrary, I dedicate a lot of my work to the dissemination of theses and projects born in school, sometimes believing in them more than the students themselves. See, for example, the Other Worlds journal, in which I published various excerpts from MA theses; and P-DPA, an archive of experimental publishing, populated by many school projects.

The reason of my embargo is instead structural. Students are encouraged to get in touch with practitioners external to their institutions to get the knowledge, points of view and expertise that they don’t have ‘in house’. If we would live in a society devoid of remunerative issues, there wouldn’t be any problem: exchange is good and necessary. The problem arises when the income of creative practitioners becomes low and intermittent, and academies begin to cut down on staff, both hour- and people-wise.

From the point of view of the student who is working on their final project, a contribution from someone external is a nice gesture justified by the fact that nobody is making money anyway. The urge to write this short text came, in fact, from people working on a project that is “student-initiated and maintained — no profit is being made and no one is making an income.” But there is another perspective to consider: the designer who takes part in the podcast contributes to the ‘buzz’ of the school’s final show, the artist who is interviewed might appear in the academy’s website, the writer who gives a talk at the student-organized panel is bringing visibility and prestige to the institution. From this perspective, these practitioners, enthusiastically invited by students, are doing unpaid work for their schools.

I came to think that carelessly accepting most invitations aggravates this state of affairs, because it hides the fact that while schools expand their reach via the innocent requests of students, their core of knowledge, expertise and culture is shrinking as a result of casualization of staff. One can envision a dystopian institution where there is no actual staff but a growing list of email addresses for students to write to… I’m exaggerating, of course, but I honestly believe that students need to be made aware of this process. This is why I’m writing this.

What to do, then? How to avoid disappointing those students who are genuinely excited about my work? Here’s what I generally do: after thanking the students for their interest, I encourage them to ‘re-route’ their informal invitation, that is, I ask them to ask the school to invite me formally for a talk, a ‘crit’, an article, etc. And you know what? It works, sometimes. This way, I got a few paid gigs as guest tutor, and thanks to that, I could dedicate the necessary attention not only to the project of the inviting student, but also to those of their peers. Needless to say, institutions are often slow, and by the time that a student’s request is approved, they might be already graduated. But there is no harm in trying, and if things seem to take too long, the guest can always decide to proceed informally.

This text was written as a contribution to the project “Structurally Screwed: Political Configurations within Design Education” by Mariana Neves and Urjuan Toosy, Experimental Communication students of the MA Visual Communication at the Royal College of Art.

March 23, 2023

In-Between Media Conference – Thoughts and Impressions

Leaving the Dreadful Days Behind

Leaving the Dreadful Days BehindGenerally, attending an INC conference means encountering a large variety of perspectives, a parade of presentation formats, and a whole bunch of diverse practices. In-Between Media was no exception. From “theory-scrolling” lecture performances (Jordi Viader Guerrero) to talk-meets-boiler room set (UKRAiNATV), from anti-clouds shamanic rituals (Lukas Engelhardt) to testimonies of visual and invisual citizen journalism (Donatella Della Ratta).

In-Between Media is the first INC conference happening after the Covid outbreak. As Geert Lovink, founder of the institute, put it in the introduction: “the promise of Going Hybrid (the research project from which the conference derives) is that of leaving behind the dreadful days of Teams and Zoom”. We all hope that the project fulfills it. Going Hybrid addresses two main issues: the presence of remote (literally and figuratively) others, and the methods of documentation of events, their afterlife one might say. Urgent developments, such as the Ukraine war, gave new meaning to this research.

Tech That Haunts You BackSpanish artist Joana Moll opened the day with a keynote on the intrusive nature of cognitive capitalism. A smoothing out of the user experience makes space for the AdTech sector to track the attention of users and create extremely detailed profiles of them. They are then grouped in seemingly absurd cohorts (“the generous dad”, if I remember well) which, however, make sense from the statistical perspective of predicting future behavior. One of the most pervasive tools for tracking and profiling is the cookie. In the project Carbolytics, Moll attempts to calculate the carbon emissions of the massive number of cookies injected by the top 1 million websites.

Joana Moll.

Joana Moll.

Moll briefly spoke about the disassociation that might be felt by the engineers and designers who work in AdTech. “How can they not see – the artist wondered – that the tech they build or promote will haunt them back?” An interest discussion arose on the mythological dimension of AdTech. To what extent their profiling claims are real? Moll pointed out that the accuracy of these profile and their adherence to the person behind the user don’t matter much, what matters is their business model – and that is undoubtedly real: “In a near future you will have to fight against those constructed profiles”, Moll concluded.

Pleasure Scroll and TikTok IlliteracyA whole conference panel was devoted to TikTok. While for some that might feel unsurprising, I think it’s quite a bold curatorial move, given the aura of frivolousness that surrounds this social media in research and academic circles. Tina Kendall delved into the challenges to overcome boredom during the lockdown and to solve the “bored-body problem” of becoming one with the couch. From this point of view, TikTok becomes “a machines that turns boredom into fun”, a boredom which, Kendall points out, is a chronic condition of networked life.

From the left: Dunja Nešović, Tina Kendall, Jordi Viader Guerrero, Agnieszka Wodzińska.

From the left: Dunja Nešović, Tina Kendall, Jordi Viader Guerrero, Agnieszka Wodzińska.

Agnieszka Wodzińska focused on the fast-paced subcultures that follow one another on TikTok: cottagecore, dark academia, and finally corecore, a sort of anti-trend that seems to be mildly critical of the platform’s logic. Wodzińska’s hypothesis is that these trends are “zombie subcultures”, since they manifest merely as simulacra of resistance. One might thinks of Benjamin’s aestheticization of politics, which is a feature of fascism. And that wouldn’t be too far-fetched, given of the elective affinities between cottagecore, the nostalgic “tradwife” trope and far-right ideology.

With his chaotic lecture performance, Jordi Viader Guerrero cheerfully disrupted the panel. Meanwhile, he managed to inject some interesting ideas on the “infinite scroll as a symbolic form”. For Guerrero, the infinite scroll should be addressed in itself, and not just as a means to navigate content. Scrolling is “a pleasure device”, an activity that goes beyond the utilitarian goal of acquiring information.

In general, I felt a certain distance between the researchers and their research subject. Kendall admitted that she had to quickly install TikTok and become familiar with it in order to study how boredom manifests there. It was a bit frustrating to hear descriptions about TikToks without actually watching them. Wodzińska’s chronicle of -cores made me think of the endless list of -isms of the avantgarde. I asked myself: to what extent the study of TikTok differs from the standard practice of average users? After all, the latter are the “core” experts of trends (pun intended). How sustainable is the idea of a scholar catching up with 2-months long waves? Can Kendall’s “TikTok illiteracy” become a tactic to avoid internalizing the platform-oriented analytical lens?

Stuck in the PastGoing Hybrid brought together various collectives to speak and discuss about their streaming practices. Margarita Osipian and Karl Moubarak talked about the collaboration between The Hmm and Hackers & Designers to develop the former’s streaming platform. Moubarak provided a detailed ‘show and tell’ of the website, speaking of the service they use (such as Mux and, previously, Google’s live captioning feature) and their limits. I like the way they frame the question of bringing users into their design. Quoting John Lee Clark, “Who invites who into who’s world?”

Cade Diehm.

Cade Diehm.

The talk of Cade Diehm, founder of the New Design Congress, was fast and furious. He introduced the Gamergate as the infiltration of far-right actors into game culture to “redpill” gamers. The New Design Congress’s antidote to the red pill is called the “para-real”, a third-space between the digital and the physical, the moment that comes before radicalization – a space of possibility, before a certain mediation becomes entrenched. This entrenching has been, according to Diehm, the main limit of tactical media: “since technology is already old when it’s implemented, we criticize the past. In that sense, our work is reactionary. We deal with systems when they’re already entrenched.”

Self-Hosting? In This Economy??How to go from the short-termism of tactics into the foresight of strategies? Is this even possible? The case of Lurk, a small group of practitioners that provides community services such as of mailing lists, chat and access to the Fediverse, gives an ambiguous feeling of disenchanted hope. As one of its co-founders, Aymeric Mansoux spoke of the history of Lurk. The idea of hosting services was born out of a frustration towards the critical tech community. The problem was that they had apparently given up on the infrastructural issue and started focusing on the user condition within closed platforms instead. Lurk believed on the contrar that dealing with infrastructure was still important, and new energy coming from the Fediverse proved they were right. At that point, the Lurk people were both “excited and exhausted”. But Mansoux’s point is that hosting independent services in 2020 is not the same than doing it in the 2000’s: the cost of life has dramatically increased while the fees of workshops (which allow for much maintenance and development work) stayed the same. The danger, according to Aymeric, is to present independent self-hosting projects in an idealized way, focusing too much on their cultural value and too little on their economic dimension. In other words, the risk is to trick good-willed artists, designers and hackers into “a pyramid scheme of free labor”. Fun times.

Aymeric Mansoux.

Aymeric Mansoux.

Lukas Engelhardt focused a bit more on the bright side of self-hosting and its potential to be the network analog of squatting (he pointed out that in the Netherlands the budget cuts to culture more or less coincide with the squat ban). Engelhardt sees the server as a temporary autonomous zone which prefiguratively shows how it is “the status quo that is unsustainable” and not its alternatives. The digital TAZ doesn’t need to be boring or ugly, and in fact the servers crafted by Lukas are beautiful sculptural objects which combine lights and 3D-printed elements to convey a novel symbolism and incarnate communal metaphors.

Lukas Engelhardt.

Lukas Engelhardt.

A server built by Lukas Engelhardt. Photo: Katarina Juričić.

A server built by Lukas Engelhardt. Photo: Katarina Juričić.

As a research project, Going Hybrid is tackling the very issue of event reporting. Being a reporter (or, more precisely, a blogger) of the event, I feel like in Inception. The problem with reports identified by the Going Hybrid folks is that it often feels like a bureaucratic requirement, something that nobody wants to write and nobody want to read. In fact report-writing is often outsourced to students or interns. The result: dry, uninspired texts chronologically organized (“x said this, y said that”).

Moving from this premise, Sepp Eckenhaussen from INC and Gijs De Heij from OSP, speaking on behalf of the consortium’s team, defined a series of needs for a report-writing workflow. It has to be fast and flexible, it should diminish the workload of reporters and ideally de-center the idea of the author towards a non-linear aggregation of perspectives. The current prototype of this workflow is based on an Etherpad document with a series of phases and instructions. The reporter writes their notes, turn them into paragraphs and then cuts and paste bits according to tags, such as questions, opinions, audience moods, etc.

Testing the prototype during a work session was a good opportunity to reflect on the role of the reporter (e.g. are they a bored intern or a professional writer?), the division of labor when it comes to writing and editing, and, as Sepp beautifully put it, “the need to expand and not diminish the reporter’s craft”.

Photos by Sonia González Diez.

October 21, 2022

New: A Slice of the Pie

Sebastian Schmieg and I recently launched a new artwork entitled A Slice of the Pie. Check it out here: https://a-slice-of-the-pie.live/

For three months, a 16 square meter LED wall installed at Kunsthalle Zurich will display a circular shape divided into six slices. A dedicated website will livestream the pie 24/7. Through the website, artists will be able to purchase one or more slices and fill them with their own artworks, thus becoming full participants in the DYOR exhibition. To fill the pie, they will have to collaborate or compete, hustle, or simply leave the final composition to chance.

Once per day, at a random time determined by an algorithm or through a paid option on the website, the pie will be minted as NFT and auctioned on Objkt.com. The profits from the sale will be shared among the artists and A Slice of the Pie.

A Slice of the Pie derives from the artists’ prolonged reflections on the gatekeeping of the art world and the monetization of the access to it. Focused on the crypto scene, the artwork provides an update of these themes, which were first explored by Lorusso and Schmieg in Projected Capital (2018). A Slice of the Pie allows both cooperation and competition, both consensual decision-making and winner-takes-it-all resolutions. The artwork is inspired by the dry language of financial charts and dashboards as well as the cutthroat design of “battle royale” games. Being launched in a time of backlash around crypto, A Slice of the Pie puts its promises of participation to the test.

June 23, 2022

“Expectations as Reality” New Essay on The New Design Congress

It’s finally online the essay derived from the talk I gave at the Yale school of Art in April. In this essay I tried to weave together various themes that are particularly close to my heart and to my world, that is, the art and design school: professional “proprioception”, the role of the intellectual, self-design, the problem of access to problems, the persistence of the two cultures, the spectacle of self-aggrandizing ethics, and the ethos of compromise. Writing it meant running into a number of contradictions, and my attempt to overcome them was not easy because it meant placing myself outside a certain antagonistic comfort zone. The result is this river of text. Read it, if you have time, and let me know what you think about it, if you feel like.

The text appears on the New Design Congress, which I highly admire for their sharp and embedded work on design politics, ethics and technology. Publishing build bridges.

April 6, 2022

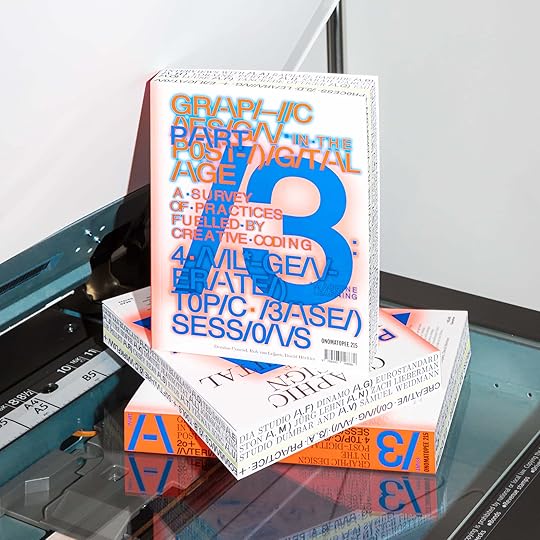

New Essay in New Book about Creative Coding

My essay “Learn to Code vs. Code to Learn” is online. Coding is an ideologically charged skill: “learn to code” is an actual injunction, and not just for designers. The propaganda around coding has not only to do with need to produce a new professional type – IBM speaks of ‘midcollars’ – but also with relocating obsolete workers and introduce emerging economies into a global production circuit. The outcomes are sometimes paradoxical. In 2019, Joe Biden addressed a crowd of puzzled miners this way: “Anyone who can throw coal into a furnace can learn to program, for God’s sake!” This is what I call learn to code.

Is software, then, the new factory? Not necessarily. Creative coding can be a laboratory, a cultural activity, and a community of practice. In this case, efficiency is secondary after all: speed (of the computer) and slowness (of the coder) coexist harmoniously. Okay, more or less harmoniously (read: debugging). So, rather than an end, coding becomes a means to learn with the computer and through it, a dialogue with the machine and with other users. This is what I call code to learn.

The essay is included in the book the book GRAPHIC DESIGN IN THE POST-DIGITAL AGE edited by Demian Conrad, Rob van Leijsen and David Héritier, designed by Johnson/Kingston, and published by Onomatopee. “Graphic Design in the Post-Digital Age” includes the work of so many friends and practitioners that I admire as well as amusing AI-generated commentary. The book can be also read in full online.

December 21, 2021

The Paradox of the Political Art & Design School – Notes on Bourdieu

During the last couple of years, in various countries such as the Netherlands, Germany and the UK, art & design schools were demanded to take an explicit political stand. They were asked, for instance, to show solidarity with marginalized groups, to take a side in international conflicts, to oppose the dominant economic system, or to actively join environmental groups. We can think of this period as an accelerated reshuffling of political urgencies. We can go even further and say that politics, as understood within art & design academies, is a process of prioritization of such urgencies.

These days I’m reading Bourdieu and I believe that his work can be useful to understand some implications of the political art & design school. One of the questions that Bourdieu helps framing is an apparently obvious one: what is a school? The French sociologist urges us to think of the school not just as a context where knowledge is acquired and shared, nor as a merely repressive institution that disciplines future white collars, but also as a market where cultural capital is formed, exchanged, sanctioned and legitimized.

Speaking of culture as a capital is crucial: it means highlighting the fact that culture can be converted into economic capital, namely, money. Scholastic capital, the amount of knowledge acquired at school, is a subset of cultural capital, but one can argue that the art & design school is slightly exceptional because the student explicitly brings in their preexisting cultural capital (interests, passions, readings, etc.) and the school helps turn it into a “practice”, which is the activity through which culture is converted into money. The art & design academy turns cultural consumers into cultural producers.

The art & design school is also a particular place also because it encourages individual self-expression. It is, in other words, the place to “become who you are”. But how can one become who they are when a set of urgencies or prepackaged political leniences steer their development? This is the paradox of political art & design education: on the one hand it promises autonomous self-realization while, on the other hand, it encourages certain urgencies, while devaluing others. A course director stating that “the climate crisis is the most important issue of our times” (as I read recently on the newspaper produced by a prominent academy) necessarily implies that other urgencies are, simply less urgent, less important, and therefore less valuable.

It’s important to point out that the delegitimization of less urgent urgencies doesn’t have to happen explicitly. Instead, it can many forms: lack of excitement in the teaching body, longer time to simply explain why something matter, less or no peers to develop the work with, etc. Less urgent urgencies will generate more friction.

It’s also crucial to remind that a certain educational institution negotiate its urgencies anyway, even when it professes its neutrality. In this sense, the explicitly political school has a quality, that is, it makes the students aware of its own process of legitimization. But if it wants to be itself aware of it, it might have to drop the liberal model of full individual self-expression by narrowing down the area of intervention within which students can express their own urgency. The political art & design school should, in other worlds, learn to become what it already is.