Sallie Showalter's Blog, page 9

October 4, 2020

Dominoes

This week I’m offering something completely different. Friday night, after trying—fruitlessly—to keep up with the news relating to the COVID-19 cases swirling among our government’s highest officials, I woke in the middle of the night with the following words running through my brain. I finally got out of bed and wrote them down.

This week I’m offering something completely different. Friday night, after trying—fruitlessly—to keep up with the news relating to the COVID-19 cases swirling among our government’s highest officials, I woke in the middle of the night with the following words running through my brain. I finally got out of bed and wrote them down.

You will see, clearly, that I have no training as a poet. I know nothing about proper forms or meter or rhyme schemes. So I hope you’ll read this as my nocturnal wordplay, an example of what happens when my subconscious wrests control from my conscious thought.

I have not altered what I captured during those feverish moments. I have not allowed subsequent news or insights to inflect these thoughts. I offer this simply as one citizen’s subliminal attempts to make sense of the harrowing world we live in.

As the Dominoes Fall I wake up and wonder:

Was it all a dream?

This fever-pitched

Swampiness holed up inside my head

For what seems like millennia

But was only long enough

To topple democracies

And eradicate futures and pasts,

Fury and white-hot hate

Scorching our throats and

Trampling our dignity

Until one by one they started to fall,

Hubris humbled by truth,

Surrendered to a force

So tiny it arrived

Undetected by the

Armies forming in our streets,

Long guns tossed over shoulders,

Chants rending the night,

A force too subtle for their

Rigid minds, too potent for their

Star Wars defense.

We had thought it a scourge,

Nature doing battle against

Man’s unconscionable crimes.

As we watched helplessly

Thousands succumb—a million—

Innocents lost,

Our heroes, our warriors,

Our suckers

Who shared this precious gift and

Delivered us, our nation,

From certain death.

Published on October 04, 2020 15:01

September 27, 2020

Broken

Hikers find refuge on the trails at West Sixth Farm outside Frankfort, Ky. Photo by Rick Showalter. Immediately after my last posting, I wanted to write about the climate disasters we have been facing this summer. I intently followed the path of hurricane Sally, as you might imagine, curious and fearful about the sort of destruction my namesake might wreak. Meanwhile, once again safe from flooding and wind damage here in central Kentucky, we rather guiltily endured our own fallout from the historical wildfires raging out west: a few gray days as lingering smoke obscured the sun. In California, Oregon, and Washington, the damage to lives, livelihoods, homes, businesses, the economy, the environment, our national forests—to normalcy—is nearly incomprehensible to those of us who don’t live there.

Hikers find refuge on the trails at West Sixth Farm outside Frankfort, Ky. Photo by Rick Showalter. Immediately after my last posting, I wanted to write about the climate disasters we have been facing this summer. I intently followed the path of hurricane Sally, as you might imagine, curious and fearful about the sort of destruction my namesake might wreak. Meanwhile, once again safe from flooding and wind damage here in central Kentucky, we rather guiltily endured our own fallout from the historical wildfires raging out west: a few gray days as lingering smoke obscured the sun. In California, Oregon, and Washington, the damage to lives, livelihoods, homes, businesses, the economy, the environment, our national forests—to normalcy—is nearly incomprehensible to those of us who don’t live there. Around the nation, our continued denial of what is causing these natural phenomena—the unabated warming of our planet that is breaking up Antarctica’s glaciers and raising sea levels and altering rain patterns and resulting in five tropical storms scuttling around the Atlantic simultaneously—reeks of insanity. Yet, we persist in our inaction.

But before I was able to wrangle my thoughts and my fury and my shame on that topic, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg died. I was paralyzed, like so many others. We all knew she had battled heroically against numerous cancers, and we were aware she had been in and out of the hospital this year. We all held our collective breath. But suddenly our optimism that she would always be victorious, always vanquish the silent oppressor, had been punctured, and we deflated like tired balloons. Today, to be hopeful seems ridiculous.

And just as I was trying to come to grips with the certainty of her death and its repercussions, Kentucky Attorney General Daniel Cameron strode to the pulpit and delivered an unctuous sermon about why Breonna Taylor matters. Evidently she matters because her innocent neighbors had to endure bullets flying through their home when a no-knock warrant was served at Taylor’s adjacent apartment. Bullets fired by an out-of-control police officer. Law and order, you know.

The bullets that landed in Breonna’s apartment, however, in Breonna, were righteous. Legal. All by the book. All to protect the neighbors’ safety.

Like so many others, I find I can’t focus. I can’t do the research I need to write accurately about the things that matter to me. I’m over-stimulated. I’m angry. I’m scared to pay attention. I have to pay attention. I don’t know where to look.

Meanwhile the pandemic rages. Football teams and their fans gather along the playing fields. Children remain at home, wondering when they will return to the classrooms many of them loathed in the “good times.” Even my elderly dog is craving different people, different running grounds, different smells. She is so sick of us. And of our palpable worry.

I have nothing positive to offer. The days are shortening. Cooler weather is upon us. Solitary walks in the woods might help (while we still have them). Or hiding under a blanket with a hot toddy or a sip of bourbon. Meanwhile, I’m fretfully lying in wait for the next cataclysmic crack in our national psyche. We know it’s coming. It’s 2020 after all.

Published on September 27, 2020 15:54

September 12, 2020

Filling in the blanks

A scene from an orphan train. Photo provided to CBS News by the National Orphan Train Complex Museum and Research Center. Once I had decided to write a novel about my grandfather, I knew that I wanted to hew to the facts of his life as closely as possible. That, of course, required extensive research—research into the public records that revealed his movements and actions, research into the other people who inhabited his world, research into the cities where he made his home, and research into the history and culture of the United States between 1900 and 1942.

A scene from an orphan train. Photo provided to CBS News by the National Orphan Train Complex Museum and Research Center. Once I had decided to write a novel about my grandfather, I knew that I wanted to hew to the facts of his life as closely as possible. That, of course, required extensive research—research into the public records that revealed his movements and actions, research into the other people who inhabited his world, research into the cities where he made his home, and research into the history and culture of the United States between 1900 and 1942.For me, one of the most difficult aspects of writing Next Train Out was knowing when it was time to stop researching and start writing. In the end, external circumstances pushed me to abandon my feeble efforts to educate myself and find the courage to put words on a page. I had enrolled in the Author Academy at the Carnegie Center for Literacy and Learning in Lexington, Ky., and my mentor wanted to see a fledgling manuscript. Although there was still research I wanted to pursue, I stopped making that my emphasis and turned my attention to creating a fictional world.

Occasionally, of course, I still had to stop writing and look up some historic detail or spend a little time pursuing a lead that had just turned up. Sometimes the leads that most intrigued me were unfortunately set aside as new distractions demanded my attention.

Earlier this summer I finally picked up the phone to pursue one of those leads. I had some notes that indicated that, in 2000, Effie Mae’s great-granddaughter had lived one county north of my home. I didn’t know if that was still the case, or whether the contact information I had for her was still valid. But since I finally had some time, I was determined to see if I could find her.

Eventually, one of the phone numbers I tried rang through.

“Hi. My name is Sallie Showalter. Is this Storme Vanover?” I asked tentatively.

“Yes.”

“Ms. Vanover, I live nearby in Scott County, and I recently wrote a novel about the woman I believe was your great-grandmother—Effie Mae Frady.”

“Yes, that’s right. Effie Mae was my grandmother Edna’s mother.”

“Well, my grandfather was married to your great-grandmother and, if you’re interested, I’d love to meet you and give you a copy of the book.”

With that prompt, Storme, who was driving her car at the time, began to share some of her family’s story. Last week I met with her for an hour in her home in northwestern Grant County, and she graciously filled in more of the details.

Storme is indeed the granddaughter of Effie Mae’s younger daughter Edna (whom I call Eileen in the book). I knew from my research (or rather, from Chuck’s research) that Edna had eventually moved to Michigan and married there. Storme was born in Detroit. What I did not know was what happened after Effie Mae left her three older children in Kentucky, including Edna, when she and her youngest son Doug moved to Cincinnati.

The 1920 census confirms that Effie and all her children were living with Effie’s brother in the Logmont coal camp. But I had to imagine what happened to the three older children Effie Mae left behind. In my naiveté—which reflects the ease of my own life—I decided that the children stuck together and successfully navigated their way to adulthood. As I look back on it now, I created a rosy moving picture story, complete with a softening scrim that subdued the hardships they must have endured.

In reality, as Storme shared with me, Edna, at some point after her seventh birthday, was put on an orphan train and landed in a Catholic orphanage. No one knows where that orphanage was, but I was distressed to read the stories of neglect and abuse at a number of those institutions in Kentucky and elsewhere.

According to Storme, Edna eventually initiated steps to take her vows as a nun. But her plans were derailed when she became pregnant by a young priest-in-training. It seems that Edna’s older sister Vivian (I call her Valarie in the book) cared for baby Shirley for some time, perhaps contrary to Edna's wishes. Edna eventually moved to Michigan, and Edna and Shirley were reunited when Shirley was six. The father of the child had no further role in their lives, and Edna and Vivian never spoke again.

This is just a glimpse into a family story full of tragedy and mésalliances as well as love and loyalty. That story is Storme’s story, and I will leave it to her to tell.

But I’ve thought about what I’ve learned from her about the fate of Effie Mae’s children. If I had reached out to Storme while I was writing the book, would I have portrayed Effie’s story any differently? Did Effie Mae know what happened to Edna? To Vivian and Lynn, her older son? Did Effie herself put Edna on that train? Or was that Edna’s father, whom Edna was devoted to? Or was it her uncle, who had taken the whole family in?

I didn’t pursue a lead while I was writing my grandfather’s story, and I now know more of the truth underlying his tale. That truth doesn’t change the work of fiction I created. But it does deepen my understanding of the lives interwoven with his own, and it reveals the hidden complexities of all our stories.

Published on September 12, 2020 14:40

August 20, 2020

Peace amid the storm

My favorite cove on Mallard Point lake. It has been a summer of unexpected connections and unexpected losses. Protesters of all colors filled the streets, and hope tempered horror. Families said their last goodbyes from afar, watching on a screen as loved ones took their final breaths. Our nation’s norms and conventions and our most reliable institutions remain under assault. It’s as if the world has tilted too far on its axis, and we’re breathlessly waiting to see if it can right itself again.

My favorite cove on Mallard Point lake. It has been a summer of unexpected connections and unexpected losses. Protesters of all colors filled the streets, and hope tempered horror. Families said their last goodbyes from afar, watching on a screen as loved ones took their final breaths. Our nation’s norms and conventions and our most reliable institutions remain under assault. It’s as if the world has tilted too far on its axis, and we’re breathlessly waiting to see if it can right itself again.Amid all the disruption and uncertainty, all the sadness and grief, I turn to nature, as always, for solace. I drop my little boat in the water and paddle to the most remote cove on our tiny lake. There I tuck myself amid the fallen logs and the loafing carp, and I watch the sun dapple the trees. I listen to the Great Blue Heron screech as it escapes my intrusion. The deer look up, and just as quickly return their attention to the new foliage near the woodland floor. The turtles wait until I float by, and then drop into the water, long after any imagined threat has passed.

I position my boat so I can gaze up the sloping hillside to my left. Then I turn my attention to the cove’s vanishing point and listen for signs of other creatures. I pivot toward the right and watch the grazing deer or intentionally spook the giant carp to engage in a little bumper pool.

This is where I go when I need to turn the world off. When the cacophony has battered my senses and I crave calm. When my thoughts are bumping against each other, creating friction and heat that prevent me from clearly discerning one from another.

The realities of our world this summer have presented most of us with more solitude than we are typically allotted. As engagements and events and opportunities to gather with friends and family have fallen off the calendar, those of us fortunate enough to be beyond the worries of work and child-rearing and aging parents have had the opportunity to assess our lives and how we live them—what we prioritize, how we spend our time, what nourishes us and strengthens us. While many have struggled with this separation or its attendant sense of isolation, I cherish it. I welcome the slower pace. I revel in quiet time for contemplation without the buzz of constant busyness. I can focus on what’s important.

You may not share my affinity for this sudden interruption of our normal activities, but I hope you, too, have found a way to embrace the unwelcome changes. That may require ceasing fretting long enough to clear the voices in our heads, or accepting that we can’t control all the forces shifting around us. Amid this tumult, we all need a place of respite, whether physical or spiritual or imaginary. I’m so lucky that mine is just a short paddle away.

Published on August 20, 2020 15:11

August 9, 2020

The Good Fight

This weekend I’m celebrating a small victory.

This weekend I’m celebrating a small victory.As a self-published author, I wear many hats. I am the sole proprietor of Murky Press, a small publishing business. I manage my business taxes and licensing requirements. I keep records of sales and inventory. I manage the business website and a variety of software licenses that help me do all the work. I publish through Amazon and IngramSpark, and I maintain accounts with each of those companies as well as with companies that provide my web domain and host my website and manage my ISBN numbers.

I’ve written recently about my rather lackadaisical marketing efforts, but I do try to come up with creative ways to get the word out about my books. BC (before COVID) I would spend time at book fairs and speak to small community groups. I post regularly to this blog to stay in touch with all of you.

And then, of course, I have to write the damn books. That may require research assistance, travel, and coordination with editors and cover designers and possibly illustrators. I do my own page layout and book design for both printed books and ebooks, so I am spared contracting with even more individuals for that work.

Of all these myriad tasks, however, the one that gives me the biggest headache is troubleshooting technical problems. Now long, long ago, I worked in the tech industry and I prided myself in keeping up with technology advancements. But I’m way past that. Things change, sometimes dramatically, every three to six months now. I’m no longer interested in keeping up, and I only fall farther and farther behind with each calendar year.

So I dread wrestling with technology problems. And they befall us all, whether we’re simply trying to manage a smart phone or an online business.

For a couple of months now, I’ve been trying to get to the bottom of the “Not secure” message that had appeared next to the Murky Press web address in some browsers. A couple of my loyal blog readers had expressed concern about encountering dire warnings relating to stolen passwords and credit card numbers.

Let me state up front that the Murky Press website was never risky to visit. I do not request passwords or credit card numbers from anyone. But I know it was unsettling to see those messages. It was for me. And I learned this summer that it could seem downright scary for some of you.

Today, as you access the Clearing the Fog blog, you may finally see a closed lock symbol indicating that the site is now secure. Whew. I hope all those frightening messages have gone away. I didn’t really do anything, in the end. But after multiple phone calls and online chats, I finally got my domain provider to talk to my website host. They changed one number in my IP address and voilà—I have now been certified as the legitimate owner of this website.

The cynic in me wonders if this recent security requirement—an “SSL certificate” for those of you in the know—is simply a way to justify staffing up the customer support lines and thereby expanding business. Perhaps if I were selling products from my website I would have more patience for this stuff.

Nonetheless it appears I have finally solved the riddle. I finally have a website that won’t scare the bejesus out of my loyal visitors. Thanks to all of you for trusting me during these uncertain times.

So raise a glass with me to one small victory over the worldwide website warlords! They stole hours and hours of my time, but you can now read future blogs with a sense of total security.

Published on August 09, 2020 19:56

August 2, 2020

The Conversation Continues

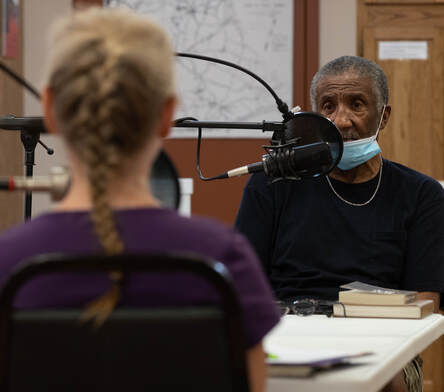

Jim Bannister, during our “family conversation” at the Hopewell Museum in Paris, Ky., July 15, 2020. Photo by Bobby Shiflet. When he walked into the meeting room, my knees nearly buckled.

Jim Bannister, during our “family conversation” at the Hopewell Museum in Paris, Ky., July 15, 2020. Photo by Bobby Shiflet. When he walked into the meeting room, my knees nearly buckled.Long and lanky, Jim Bannister physically resembles his great-uncle, George Carter. From the way Bannister heard his grandmother describe her brother, it seems the two men also share some character traits. Both are genial and gracious, polite and respectful. (Quite a contrast from how Carter was portrayed in newspaper articles justifying his fate.) I don’t know whether Carter also shared Bannister’s gentle garrulity or his bracing honesty.

Bannister has lived a long and full life. After retiring from one of our nation’s iconic companies, he stumbled into a second career that filled his next 15 years. He is immensely proud of his three children, five grandchildren, and two great-grandchildren.

George Carter never had a chance to see what he could make of his life. At 22, he was murdered by a mob seeking misplaced justice for my great-grandmother. He never got to see his two daughters—an infant and a toddler when he died—grow into young women.

Although I have no evidence that my family was directly involved in that mob, the actions of those men must have had my great-grandparents’ tacit approval. The long, detailed, nearly baroque newspaper article that described the event never mentioned that Mrs. Board was outraged by this rogue justice. If that had been the case, I have to imagine the newspaper’s owner—the husband of her good friend—would have felt obligated to acknowledge it. Or at least allude that the mob’s actions were shocking to her “gentle sensibilities.” Instead, the editor felt comfortable printing her name in bold type just below the booming headline “JUDGE LYNCH.”

And it was this silent acceptance that made it all so sinister. That same unspoken code underpins the racism that roils us today. It informs our wordless interpretation of the symbols of our bloody history: the monument that looms over a city, the flag draped along a front porch, the arched gate that tells a tale that only a few people can hear.

My ancestors helped gird this “infrastructure of oppression” that former President Obama referenced during his eulogy for Congressman John Lewis, a national hero who dedicated his life to shouting out loud what some would prefer to keep under a bushel. Who demanded that we unshackle ourselves from the myths and the lies we have told ourselves and exclaim that all men are indeed equal and therefore deserve an equal chance at a long and full life.

I’m still trying to understand why Jim Bannister was willing to meet with me, a member of the family that introduced such horror into his own. I think, in part, he was determined to break the silence that surrounded this piece of his family’s history. A silence that he bravely mimicked at a very young age when he chose not to tell his grandmother about the beatings he endured at the hands of a black teacher. It was the oppressiveness of all that silence that burdened him. Why would no one talk about it? Why could he not learn more about an incident so significant to his beloved grandmother?

Going into our initial meeting, I mistakenly thought that George Carter was Jim Bannister’s great-great-uncle. That seemed fairly removed from his own life. But my heart began racing when I realized early in our conversation that we were talking about his grandmother’s brother. The grandmother who had raised him. A woman he was around every day. George Carter would have been immediate family to him.

I, on the other hand, had never known my grandfather, the one who allegedly identified George Carter at the jail when he was only eight years old. My mother had never known him. It all feels like distant history for me.

But with Jim Bannister’s help, I will be able to feel a little more sharply the pain my family caused. That’s what I need to propel me to search for another small step I can take to help right some of these generational wrongs, to heed John Lewis’ words in his final op-ed:

“Democracy is not a state. It is an act, and each generation must do its part to help build what we called the Beloved Community, a nation and world society at peace with itself.”

I recently called Mr. Bannister, breaking another brief silence that hung between us, to let him know that I had discovered we had both worked for the same company. To let him know there was something else we had in common. We had a long and delightful conversation. He shared more about growing up in Paris just after World War II, as well as a few tidbits about his children’s and grandchildren’s accomplishments. When I got off the phone, I was grinning from ear to ear. I have a new friend. And I couldn’t be happier. Read coverage of the conversation in the Lexington Herald-Leader [July 30, 2020]Listen to the full conversation [July 15, 2020]Listen to the segment aired on WEKU’s Eastern Standard program [July 30, 2020]—also available as a podcast on iTunes, Stitcher, Google Play, and NPR One.

Published on August 02, 2020 11:15

July 26, 2020

Word of Mouth

How I’ve spent my summer marketing Next Train Out. Photo by Rick Showalter. As traditional book fairs, author readings and, yes, book launch parties remain taboo, digitally savvy authors come up with creative ways to alert likely readers to their new books.

How I’ve spent my summer marketing Next Train Out. Photo by Rick Showalter. As traditional book fairs, author readings and, yes, book launch parties remain taboo, digitally savvy authors come up with creative ways to alert likely readers to their new books.The rest of us rely on friends, family, and colleagues to spread the word.

Once the pandemic tightened its sticky little fingers around our collective throats, I pretty much gave up on marketing. I tried to focus on the blog, just to stay in touch with all of you. But I largely threw up my hands and said, “It’s God’s will.” Then I sat on my butt and ate bonbons.

Slowly, however, as the initial shock of the lockdown lifted, the wheels of the old network began to grind. Thirty years of job-hopping started to pay off. A couple of folks I exchanged pleasantries with during my working days felt sorry for me and offered to help.

First, Tom Eblen, formerly with the Lexington Herald-Leader and now the literary liaison with the Carnegie Center for Literacy and Learning in Lexington, Ky., reached out to me about doing an online reading to post on the Center’s Facebook page. Being the Luddite and contrarian I am, I’m not on Facebook. But I figured millions are, so surely two or three potential readers might become bewitched by the tale of Lyons and Effie Mae. I grumblingly agreed. After a couple of technical glitches, I managed to submit a seven-minute reading that suited his purposes. Then Tom Martin poked his head up from all the reporting the pandemic had generated for his weekly radio program on WEKU, Eastern Standard. Tom and I had planned to do this interview in April, but waiting until July gave me plenty of time to rest up before I had to perform again. Tom is a consummate interviewer—and an excellent editor. He can make anyone sound good, thank goodness. I know some of you caught the original airing of this interview on July 16.

Now I figure if I sit patiently in my office—or on my dock—maybe another opportunity or two will come. Perhaps I’ll even sell a couple more books. Meanwhile, I’ll continue to lean on the excuse that there’s not a damn thing I can do to market this book during a pandemic.

Coming up On Thursday, July 30, at 11 a.m. on WEKU’s Eastern Standard, Tom Martin will present his remarkable summary of the conversation I had on July 15 with George Carter’s great-nephew, Jim Bannister. Listen to a preview. If you can’t catch the original airing, it will be available from Eastern Standard’s archives afterwards. I’ll write more about this experience for Clearing the Fog soon. That post will include links to the WEKU broadcast and to various newspaper articles about the conversation.

Published on July 26, 2020 14:53

July 20, 2020

Culture Shock

The beautiful Eastern Kentucky mountains. Photo provided by Joe Anthony. Joe Anthony, of Lexington, Ky., writes about how we are all the same—yet different.

The beautiful Eastern Kentucky mountains. Photo provided by Joe Anthony. Joe Anthony, of Lexington, Ky., writes about how we are all the same—yet different.My wife and I and our 14-month-old daughter moved from New York’s Upper West Side to Hazard, Kentucky, in August 1980. Culture shock is what people gasp when they first hear that. Culture shock. I’m trying to think what they mean by that term.

I’ve written a couple Appalachian novels and some stories where I play with the outsider/insider theme—showing how different expectations, different stereotypes, and different ways of communicating all make for an unexpected mix. Perhaps that’s culture shock. You expect certain things, certain reactions—or you don’t expect them and you get them. Did I know I was in a different place when I first moved to Hazard?

Not really. Of course, there were the mountains. And accents. But I had taught in Brooklyn. You want accents? Spanish, Russian, Inner-city Black, African, and so on. At least Hazard’s accents were more or less the same—though deep in the county, places like Bulan, Kentucky—they were a little hard on the ear. But even then, you just needed a pause to understand. Like old fashioned-long-distance telephone calls. “Oh, that’s what he said.”

So a place with accents—like Maine—only with mountains. How pretty. Look how the fog catches in the valleys in the morning, how it coats the rivers. But just a different part of America. The same people.

A school of thought exists, a philosophy, a theology, that all people are the same. I’ve lived my life on that premise, and my writing, both on Appalachia and on race, center around that idea. But I’m not sure. Sometimes the foreign is so distinct that one wonders: how do I understand this?

My first inkling that I was in a different place was the wary friendliness I encountered. I gradually understood that they had an idea of a New Yorker that didn’t match who I was. Brash self-confidence wasn’t my style. A certain cognitive dissonance occurred as they tried to adjust what they saw with what they expected.

On the other hand, they expected me to fit them into stereotypes. But they again underestimated how ignorant I was: I didn’t know the stereotypes. I only learned the stereotypes after I had seen the reality. That’s not the natural order for embracing stereotypes: they really can’t take root.

Of course, I understood quickly when I’d be invited to insult Appalachians as in “You must think we talk terrible.” I had taught English in inner-city Brooklyn. I thought Appalachians’ English their English. But I could sense the hurt beneath the lead-in query.

My first real lessons in living in a foreign place were in finding that the way between two places is not necessarily a straight line: e.g., asking for something. For a small class, I had to ask all of the registered students if they had any problem with a changed time. I asked each one, personally, all twelve. No problem, all twelve answered. So I changed the time.

One hundred percent. Each of the twelve had a major problem: a conflicting class, a ride home missed, a child that needed to be picked up. All of them. But I had asked, I wailed.

Here’s what I think happened. I am not New York arrogant (I hope) but I am New York direct. Yes or no? Problem or not? I was ready for a no answer, but they perceived, correctly, that I wanted yes. So they said yes. Were they lying to me? No. They gave me soft yeses. Yessss. An Appalachian soft yes is a New York no. I would have known that if I had spoken the language. I would have pursued the question with “Are you sure?” and maybe then I would have heard of the child, or the class, or the ride. Maybe not. If it hadn’t been that all twelve students had problems, two or three would have kept quiet and quietly dropped. Better that than an unpleasant conflict. My New York students, stereotyping here a bit, wouldn’t have hesitated to tell me the facts—and maybe abuse me a bit for even asking.

I would tell my classes in Hazard that they were much more complicated in their communication styles than any New Yorkers I knew. They’d laugh and not quite believe me, but it was true. I’d think: what do they mean by that? Where are they coming from?

In my first novel, Peril, Kentucky , “playing” off Hazard, Kentucky, my main protagonist is a well-meaning New Yorker who plows ahead with her decent intentions—doing some good but so oblivious to where she is. Here are my words, she always seems to be saying. They mean this. They always mean this. How could they mean something else to you? I’ll say them again. Listen this time.

Terrible things happen. It’s not all her fault. None of it is morally her fault. But if she had been culturally humble, perhaps some of it could have been avoided.

“I don’t care to,” is the fun expression that sort of captures the foreign place my protagonist, Linda, and I both found ourselves in. In Jersey, it means you don’t want to do it. You want to play ball? “I don’t care to.” So my shock showed on my face when I asked someone to pass the salt and I got, "I don’t care to.” OK. You’re right. I should use less salt. Or. Do you mind if I reach? “I don’t care to.”

Of course, it means the exact opposite in Kentucky: I don’t mind at all doing what you ask. Almost everyone I know from the East has that story. I don’t know that it’s just a verbal tic. I think it might indicate a whole frame of communication that is different. In Jersey, we might respond with a “no problem” or “sure” or, more likely, silence and the salt. But in Kentucky, at least Eastern Kentucky, relationships were more like a dance with structured steps. And if you skipped those steps, or if you shorthand them as in my class time question, you wouldn’t get a full answer, or a coherent one. You got a sign that the conversation was happening on a different plane.

I got almost three books out of that ambiguity so I’m not complaining. So much more to say about culture shock: smiles that weren’t invitations in, but gates that kept you out. I haven’t mentioned the very different ideas concerning solitude, community, and isolation. But this is enough for now.

Published on July 20, 2020 14:02

July 13, 2020

Birding in a Time of COVID

Birding might surprise you. A Red-Winged Blackbird in flight near Camp Last Resort, 2015. (Photo by Rick Showalter) David Hoefer of Louisville, Ky., the co-editor of The Last Resort, offers an antidote for our trying times.

Birding might surprise you. A Red-Winged Blackbird in flight near Camp Last Resort, 2015. (Photo by Rick Showalter) David Hoefer of Louisville, Ky., the co-editor of The Last Resort, offers an antidote for our trying times.The last several months have brought us the unsatisfying spectacle of a nation of 325 million people devising on-the-fly strategies to outwit a virus. Yes, there is a novel pathogen on the loose and, yes, certain groups, mostly the elderly and other persons with compromised immune systems, do appear to have a heightened risk of serious infection. What remains less clear is the actual extent of the threat to other segments of the population. The public-health response has evolved over time—remember gloves sí, masks no?—but one persistent feature has been the need to close up the populace indoors, away from others of our kind.

This has proven problematic because modern humans—Homo sapiens—are profoundly social creatures. Efforts at selling “virtual communities” as replacements for flesh-and-blood gatherings are almost laughably off the mark. In reality, the antisocial practices of “social distancing” play to the worst aspects of American culture: the tendency to produce isolated individuals amusing themselves with trivial pursuits while failing at healthy, long-term relationships with family, friends, lovers, and neighbors. The longer we drag this out, the more likely unintended (and negative) consequences become.

Be like Pud One sensible alternative to exile-at-home is the Great Outdoors. It’s becoming increasingly clear that fresh air and sunshine have been underutilized in our often-panicky response to COVID-19. Hiking, biking, picnicking, boating, fishing, and hunting are all good reasons for going outside, where the Earth’s ultimate limits remain hugely liberating, when compared to the four snug walls of our houses and apartments.

We used to understand that outdoor activities were beneficial for us. That was certainly the case for Pud Goodlett and the gang in The Last Resort. They went to the trouble of constructing a home-away-from-home, as a means of ready access to the varied and gracious Salt River environment of Anderson County, Kentucky. The cabin itself luxuriated in nature, with spiders, birds, weather, and even lightning intruding on occasion. This was no place to hide from the external world, calculating defenses against every potential risk to comfort and safety.

Though Pud was a budding botanist, his journals make evident a sustained interest in the taxonomic class of Aves—our fine-feathered friends of the sky. Taken seriously, birding is an outdoor diversion of the very best sort, appealing about equally to the beauty-seeking soul and truth-hungry mind of anyone who engages in it. A great resource for beginning birders learning the ropes or lapsed veterans knocking off the rust is the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Corny Orny, as I call it, offers online classes, extensive databases, and cutting-edge digital apps that can greatly enrich your birding experience.

So be like Pud and light out for the world, even if it’s only your backyard or the local park. Our economy isn’t the only thing that’s been hurt by the corona shutdown. It’s time for us to get back to the business of being human.

Published on July 13, 2020 18:51

July 6, 2020

Extended Family

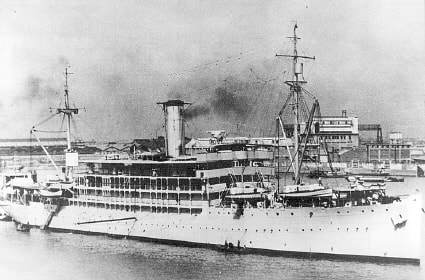

Effie Mae’s son Doug served on the USS Canopus, a U.S. Navy submarine tender, during the 1930s. Doug died in 1988, three years before my mother. Yesterday I talked with Effie Mae’s granddaughter. Doug’s daughter.

Effie Mae’s son Doug served on the USS Canopus, a U.S. Navy submarine tender, during the 1930s. Doug died in 1988, three years before my mother. Yesterday I talked with Effie Mae’s granddaughter. Doug’s daughter.Many of you who have read Next Train Out know that the novel is based on the life of my grandfather, William Lyons Board. You know that most of the major events in the book are factual, according to historical records uncovered over years of research.

But you may not have fully understood that Effie Mae, the other narrator in the novel, was also drawn nearly completely from records of her life. The same goes for Doug, her youngest son.

Some years ago my friend and collaborator, Chuck Camp, found Kathleen, Effie Mae’s granddaughter, in the Washington, D. C. area. He talked to her a few times, pressed her about what she knew about her grandmother, who had died before she was born. The details were few, but Kathleen was able to relay some sense of the warm relationship her dad had with both his mother, Effie Mae, and his stepfather, “Bill” Board.

Chuck and I had tried to arrange a trip to meet Kathleen and interview her in person, but we kept bumping into scheduling obstacles. Eventually, I shifted from a focus on research to writing the novel, and I threw all my energy into getting words down on the page.

All along, of course, I knew Kathleen was out there, and I hoped to finally meet her. I had planned to invite her as a guest of honor to the book launch party that had been scheduled for April. When the coronavirus forced us to abandon those plans, I once again turned my attention to other things.

So it wasn’t until yesterday that I picked up the phone and “dialed” the number I had for her, not knowing if it would still be valid. As I was leaving a message, she picked up. We had a delightful conversation, and I am now more eager than ever to visit her in person—whenever that is possible. I confirmed some things we have in common: she and I both grew up in Baltimore, and we both spent at least part of our careers as technical writers. (One distinction: she is still working and loves her job.) In a brief email I sent to her afterwards, I suggested that perhaps we are “step-grandsisters,” her grandmother having married my grandfather.

I have mailed her a copy of the book, and I look forward to discussing it with her after she has read it. No doubt much of it will feel familiar to her. She may also learn some things about her grandmother’s life. And I’m certain she’ll learn a good bit about the man her grandmother married during the Great Depression.

I’ve written before about how these writing projects I’ve undertaken over the last four years have led my life in unexpected directions. I’ve made significant new connections with people whose lives somehow intersected with members of my family. It has been genuinely remarkable. And I’m more and more grateful every day.

Published on July 06, 2020 10:01