Sallie Showalter's Blog, page 7

March 6, 2021

Skulduggery

Does this young fella look like a criminal? As an adult, he stole over $20,000. I am a descendant of thieves.

Does this young fella look like a criminal? As an adult, he stole over $20,000. I am a descendant of thieves. One grandfather—while a partner in an automobile dealership—stole a friend’s 1920 Oakland Sedan and then wrecked it, resulting in damages to the tune of $1,000. During the Great Depression, my other grandfather evidently mismanaged some county funds, perhaps to his benefit. About the same time, my maternal grandmother’s half-brother, while working in the Kentucky Auditor’s office, pocketed more than $20,000 in state money in an elaborate six-year scheme. In 1885, my great-great uncle was charged with embezzlement in Kentucky—a great embarrassment, evidently, to his many benefactors, including U.S. Senator Joseph Clay Stiles Blackburn. In 1897, the same uncle was charged with forgery in California.

Embezzlers. Grifters. Hucksters. Glory be.

Before their alleged malfeasance was exposed, each man had by all accounts been a well-respected government functionary or businessman, a churchgoer from a locally recognized family. There had been not a whiff of impropriety, as far as I’m aware.

But something compelled each of them to make a bad decision, or a series of them—to take risks that may have been uncharacteristic of their normal dealings. The temptation was too great. Human frailty prevailed.

When the repercussions became apparent, two ran away, leaving Kentucky behind. Two didn’t live to see the matter resolved. Family paid the price of their perfidy.

We are more than our misdeeds, of course. We are all complex: good and bad, wise and foolish, brave and cowardly, generous and selfish. None of us can predict how we might have responded to their particular circumstances. As I chew on another juicy tidbit about my mysterious ancestors, I have to remind myself not to let that one savory crumb define them.

I have learned that families don’t tend to share this information with each other. Why not just sweep it under that very lumpy rug? Nothing good could come from talking about the family troubles. After all, these problems were all in the past, safely locked away in faltering memory. That is, until some nosy granddaughter starts picking through yellowed newspaper articles.

On the one hand, I am happy that my ancestors were “colorful.” I would have lost interest long ago if they had only been Sunday School superintendents and hard-working family providers. In small towns like Lawrenceburg and Paris and Harrodsburg, some of that probity would have gotten them mentions in the local newspapers. As it was, the society pages detailed their comings and goings. But, as always, I imagine the scandals sold more papers.

What this teaches us, of course, is that our ancestors were just as complicated as we are. Each of us has had moments when we filled with pride and moments we hope will never be known to any other living soul. Unfortunately for my ancestors, these particular moments of weakness, these missteps were captured by the press—or the courts.

If we’re lucky, no yet-to-be-born great-granddaughter will stumble across accounts of our failings. Perhaps the public persona we’ve all so carefully crafted for our friends and families—and ourselves—will hold.

But our moral failings partially define us, whether we want to admit it or not. We’re not just the sum of the good things. It’s never that simple.

Some of my ancestors were thieves. And loving husbands and fathers. And hard-working citizens. And human beings, as inscrutable as we all are. Sometimes even to ourselves.

I would be remiss if I didn’t acknowledge my good friend Tessa Bishop Hoggard, who provided many of the newspaper clippings related to these incidents. Lord knows why she has found my family so interesting, but I am indebted to her research prowess and the gift of her time.

Published on March 06, 2021 17:59

February 27, 2021

I WAS BLIND

Cathy Eads, of Atlanta, Ga., describes her awakening to the racial inequities that remain endemic in U.S. society. If you would like to submit a post to Clearing the Fog, please contact us here.

Cathy Eads, of Atlanta, Ga., describes her awakening to the racial inequities that remain endemic in U.S. society. If you would like to submit a post to Clearing the Fog, please contact us here. I was blind, but now I see.

As Black History Month 2021 comes to a close, I’m also marking nearly a year of much more time, and need, for mulling over the human condition. So, I’ve been reflecting on the evolution of my awareness of racism. I grew up a cis white female in central Kentucky. I went to a very small elementary school with zero Black students and a high school of 800 kids with around 15-20 Black students. I had much more experience with the Huxtable family, Sanford and Son, and the Jeffersons than I did with real Black people. It would be generous to describe my view of the Black experience and racial inequity as narrow.

When 17-year-old Trayvon Martin was shot and killed, the scales fell from my eyes. At the time, my second son, a white boy, and his close friend and neighbor, a Black boy, were 12. It struck me suddenly that my son’s friend, my kind neighbors’ child, could have easily been killed in cold blood for walking around at night in a hoodie, just like Trayvon. This fact made me sick to my stomach, and it readjusted my understanding of racism. I hadn’t fully realized until then how a person’s Blackness still made him or her a target, and how a person’s whiteness gave him or her protection.

That day I started to understand the concept of white privilege. I realized I had never felt the need to have a talk with my sons about how to act around police in order to save their lives during a traffic stop, or anywhere else. I never had to tell them to keep their hands out of their pockets when in a store, and to make sure they got a receipt, and a bag, at the checkout. I never feared that when they went out at night with friends, they might be shot and never come home. I felt guilty and embarrassed by my depth of ignorance around racial issues.

In the last few years, I’ve learned more about the history of policing, cash bail, and mass incarceration. I’ve read the statistics on Black women’s health and rates of Black maternal death. I’ve watched the reports of how the coronavirus has stolen a disproportionate number of Black lives. I’ve heard the stories of racially motivated voter suppression laws, the higher rates of toxic pollution present near neighborhoods populated mostly by people of color, the racial bias in education and testing, and systemic racism that permeates nearly every institution throughout the United States and weaves its threads throughout our culture.

I used to claim, “I’m not racist.” Now I know this: it’s impossible to escape the effects of racist ideas in a society that was built on racism and has laws that support racist policies still today. I believe it’s time we all consider getting on board with the Avenue Q song and just admit it—“Everyone’s a Little Bit Racist,” because we have grown up in a deeply racist society.

Ibram X. Kendi explains that the only way out of this quagmire is to become antiracist. It’s not enough to try to be “not racist.” If people want to bring about changes that promote equity, we have to actively work to become antiracist individuals. From that place, we can work to bring about antiracist policies. His book How To Be An Antiracist has helped me see even more of my blind spots and learn how to overcome them, along with ways our communities, organizations, and laws can become antiracist. He shares stories of his lived experience along with the history of race as a social construct created to achieve a sense of supremacy and privilege for some people, and to strip it from others.

Regardless of our physical characteristics and beliefs, I am certain that until all of us feel safe, cared for, respected, and valued, none of us truly are. Working at becoming antiracist is one step I can take toward promoting a more secure existence. I still have much to learn.

Published on February 27, 2021 09:30

February 15, 2021

Acceptance

Image of a peaceful protest: the Women's March in Washington, D.C., the day after the 45th President's inauguration. I was there. Photo by Mary Henson. And so he has been acquitted, as we all anticipated. His loyalists never abandoned him, not really, even if some publicly wavered moments after he put their lives at risk. Because of that undying fealty, and despite what some pundits are saying, I fully believe he will run again. Why wouldn’t he? He craves the white-hot heat of that spotlight in the political crucible. He will crush all comers.

Image of a peaceful protest: the Women's March in Washington, D.C., the day after the 45th President's inauguration. I was there. Photo by Mary Henson. And so he has been acquitted, as we all anticipated. His loyalists never abandoned him, not really, even if some publicly wavered moments after he put their lives at risk. Because of that undying fealty, and despite what some pundits are saying, I fully believe he will run again. Why wouldn’t he? He craves the white-hot heat of that spotlight in the political crucible. He will crush all comers.As I watched the brilliant impeachment managers present their evidence last week, I alternated between traumatized, tearful, and comforted. Comforted because I realized how much I needed someone to confirm that this has all been real. I needed to see the horrors of his presidency presented in a cogent and organized way. Seeing the chaos neatly packaged helped me breathe again.

It wasn’t just a terrifying, perpetual nightmare. Others saw it, too. Around the world, they were watching.

I wish I could believe it is over. But his chilling words on Saturday tell us otherwise: “Our historic, patriotic and beautiful movement to Make America Great Again has only just begun.”

We are all exhausted, and I intend to heed our duly elected President’s calls to move on. But we must remain vigilant. We cannot allow our hope and our relief to blind us to the anger and the violence of Trump’s toxic brew. We watched it boil over on January 6. He will turn up the heat again.

Published on February 15, 2021 09:34

February 8, 2021

Truth in Fiction

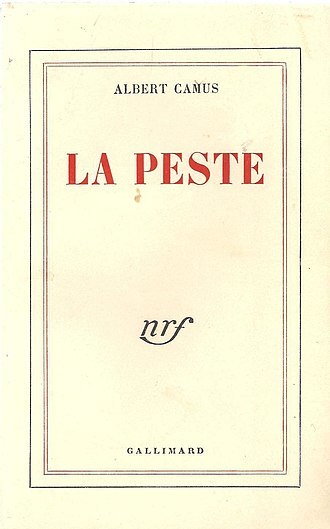

The first edition of Albert Camus’ “La Peste,” or “The Plague,” published in 1947. The novel is a fictional telling of a 20th-century epidemic. Its “truths” seem all too real to contemporary readers. Back in December, in the awful year of our Lord 2020, I happened to flip on a news program just as author Salman Rushdie pronounced, “Lies are a way of obscuring the truth. Fiction is a way of revealing the truth.”

The first edition of Albert Camus’ “La Peste,” or “The Plague,” published in 1947. The novel is a fictional telling of a 20th-century epidemic. Its “truths” seem all too real to contemporary readers. Back in December, in the awful year of our Lord 2020, I happened to flip on a news program just as author Salman Rushdie pronounced, “Lies are a way of obscuring the truth. Fiction is a way of revealing the truth.”Having taken numerous classes and read many books on fiction writing in recent years, this concept was not novel to me. (Sorry…) Nor is it original to Rushdie, of course. Writers Albert Camus and Jessamyn West, for example, famously used nearly the same words to relay the same idea.

But I hurriedly scribbled the words on a pad of paper that I’ve learned to keep in front of the TV—my oracle for inerrant wisdom—and they’ve rolled around in my consciousness ever since.

This week our nation will be subjected to yet another impeachment trial of Former President Donald J. Trump (or “the 45th President Donald J. Trump,” as he evidently prefers to be addressed). He is in this predicament once again because of his lies. He lied about the fairness of the election before the election, and he lied about the results of the election afterwards. He also pressed other people, such as Georgia election officials, to lie for him. Many, many people believed his lies, and, ultimately, his lies led to the insurrection at the Capitol on January 6. People died, and other people’s lives were threatened.

Trump obviously felt it was to his advantage to “obscure the truth.” If he is not convicted, if he never faces any further accountability for his lies or the damage they caused, what deterrents will there be for other elected officials not to lie to further their agenda? Or to cry “Fraud!” every time they lose an election?

In fact, our country seems to be so awash in lies that I’m not sure how we ever find our way back to the truth. Perhaps that’s why Rushdie’s comments have stayed with me.

Some of the most powerful—or memorable—fiction tells the stories of ordinary people who find themselves in horrific situations: war, poverty, imprisonment, abuse, persecution, pandemics, social or political upheaval. It’s by temporarily inhabiting these fictional characters, seeing their world through their eyes and ears and emotions, that we can begin to understand their truth. It’s not until we actually feel ourselves in that battle or in that degrading circumstance, or we feel that hunger or those taunts or that pain, that we begin to fully grasp their reality.

It may seem odd at first to think that a made-up story taking place in a made-up world is where we may logically find the most truth. But perhaps that imaginary incarnation permits greater honesty. Or perhaps it helps remove our own prejudices so we can see things more clearly.

Which leads me to ask: Will we have to wait until some great works of imagination are written about these dark days—these days spent watching our democracy teeter on the brink—before we are able to fully untangle all the lies? Or can a nation of disparate peoples with disparate experiences and viewpoints finally, through sheer will, recognize a common truth so we can heal this country?

This week the impeachment managers will carefully present all of the facts they have collected, drawing the clearest picture they can to support their contention that the former president incited the insurrection. But can they “reveal the truth” in a way that the majority of our citizens, let alone two-thirds of the Senate, will accept it?

We’ve already seen most of the evidence. Many of us watched it play out in real time. But, still, we don’t agree on the appropriate response. The truth remains elusive. Fiction may be our last hope.

Published on February 08, 2021 20:17

February 2, 2021

Routine Enumeration

Last month I found a small trove of family photos from the 1800s and early 1900s that I didn’t recall having seen before. I believe this is my great-grandmother, Mary Lake Barnes Board. It’s Black History Month, so it’s time for more reckoning.

Last month I found a small trove of family photos from the 1800s and early 1900s that I didn’t recall having seen before. I believe this is my great-grandmother, Mary Lake Barnes Board. It’s Black History Month, so it’s time for more reckoning.I have written freely in this blog about my family’s role in the lynching of a Black man, George Carter, in Paris, Ky., in 1901. I have written about my horror in learning about that incident. I wrote last summer about my rising fury at the unending injustice in this country that has led to the unconscionable loss of Black lives, tragedies that have been ongoing for generations but which have become more public with the advent of cell phone videos. I remain angry and disgusted with the lack of progress on the underlying issues that allow this to continue. I hope to write more about that before February comes to an end, and we give ourselves permission to stop thinking about these things until next February.

Right now, however, I need to talk about the family Bible.

I remember this Bible being displayed on a dropleaf cherry table in front of the picture window in our living room in Lawrenceburg, Ky., when I was a child. It was an enormous, handsome, heavy book, in good condition for a book of its age. I remember flipping through it; I remember noticing handwriting on some of the pages. But I don’t believe I could have told you what branch of my family it represented or anything about the people whose births and deaths and marriages had been noted.

Recently a family member shared some photos she had taken of those pages. I immediately recognized that the Bible was yet another relic of my missing grandfather’s family, the grandfather who abandoned my mother shortly after her birth. The Bible was published in 1848, so the Bible first belonged to my grandfather Lyons Board’s grandparents, Dr. L. D. Barnes and his wife, Mary Parker Roseberry Barnes, of Paris, Ky.

After all the research I—and others—have done into that family over the past ten years or so, I now recognize the names. Those of you who have read Next Train Out might, too. There’s the marriage of Dr. Barnes’ daughter, Mary Lake Barnes, to William Ellery Board, originally of Harrodsburg, in 1888. There’s the marriage of their only surviving son, William Lyons Board, to Nell Hardeman Marrs of Lawrenceburg, in 1920. There are the births—and the deaths—of all the children who didn’t live to adulthood, or didn’t even survive infancy.

And there are the births of the “servants.”

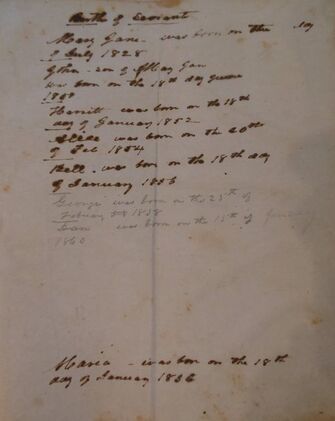

And there are the births of the “servants.”The servants are identified only by first names: Mary Jane, John, Harriett, Alice, Bell, George, Dan, and Maria. The listing is separate from the “Family Record” listed in a fine hand on decorative pages. The handwriting on the servants page is less careful and difficult to read. It grieves me that I may not have all of the names correct. Another thing we have learned this year is how important it is to say their names.

All of the servants were born between 1828 and 1860. All were born, I have to assume, into slavery.

I don’t know that for certain, of course, And it’s possible they had been freed by the time they were listed in the family Bible. But any other scenario is hard to imagine in central Kentucky before the Civil War in a family of some status living in a county with a large population of slaves working expansive agricultural land. The fact that they are included in the Bible makes me want to believe that they were indeed considered members of the household and were treated gently and respectfully and were well loved by the Barnes family.

None of that excuses the fact that some or all of them were at some point the property of the Barneses.

I had already discovered some time ago that at least three of the four branches of my family once owned a small number of slaves, probably all doing domestic household work. I had already reckoned with that in some small way. It was not a surprise to discover this listing of the Barnes family servants. But it remains painful to see the evidence handwritten in such a personal way in the family Bible.

Many of us from the South share a similar family history. It’s remote to us now. We’re talking about more than 150 years ago, after all. Nonetheless, I feel it’s important not to deny our intimate connections—no matter how tenuous, no matter how seemingly innocent—to the national shame our country has to bear, and bear witness to. My family played a role. The Bible tells me so.

Published on February 02, 2021 16:54

January 28, 2021

“The Solace of Snow”

Thankfully, Lucy loves snow as much as I do. The words leaped off the cover of the February-March issue of National Wildlife, the magazine of the National Wildlife Federation. Looking directly at me on the cover was an adorable young American marten—a tawny brown weasel with a bushy tail, a species I knew nothing about that evidently builds tunnels under the snow for warmth and easy hunting.

Thankfully, Lucy loves snow as much as I do. The words leaped off the cover of the February-March issue of National Wildlife, the magazine of the National Wildlife Federation. Looking directly at me on the cover was an adorable young American marten—a tawny brown weasel with a bushy tail, a species I knew nothing about that evidently builds tunnels under the snow for warmth and easy hunting. The phrase stayed with me—“The Solace of Snow”—as I awaited a little snowfall here in central Kentucky. This morning, I awoke to Kentucky’s version of a winter wonderland. Out walking Lucy, I talked to a neighbor who was headed to Florida for some sunshine and golf. The mail carrier stopped to chat and said she’d be fine if this were the last snow she ever saw in her life. I piped up, saying, “I’d like to have snow on the ground from December 1 to March 31”—and the conversation abruptly stopped. They stared at me. My undying love for snow is not popular.

A snowfall calms me. It purifies the landscape, covering all the world’s blemishes, all the ugliness, all the winter rot. I love the crisp, cold air. I love crunching through the snow or kicking up the powder. A beautiful snowfall renews me, the way crocuses pushing through the snow might give others hope.

For me, snow does indeed offer solace, something that has been in short supply over the last months.

Reading the article “A Fading Winter Blanket,” I learn how diminishing snowfall is affecting a wide range of animals, from the marten to the polar bear to ruffled grouse to the tiny Karner blue butterfly in upstate New York, which lays its eggs on the stems of wild blue lupine, expecting them to be warmed and protected by persistent snowpack all winter. As the earth has warmed, that hasn’t been the case, so the Karner blue butterfly population is at risk. Polar bears are struggling to find the deep snow needed for birthing dens. Mountain goats in the American West seek increasingly rare patches of snow year-round to prevent them from overheating.

The natural world as we know it depends on snow, for a wide variety of reasons. As our weather becomes more extreme—too much snow in some places, too little elsewhere, glaciers melting, sea levels rising—many species suffer. Some will adapt. Some will disappear. We’ll grieve them when it’s too late.

Meanwhile, I’ll keep longing for the blanketing snows of my childhood, for long days on the sledding hill and soaking wet snow gear draped around the house. For the break in routine that a heavy snow compels—the only excuse you need to revel momentarily in its enchanting beauty.

Published on January 28, 2021 14:54

January 24, 2021

The Bus to Happy

Joe Ford, of Louisville, Ky., may have found what we're all looking for. If you would like to submit a post to Clearing the Fog, please contact us here.

Joe Ford, of Louisville, Ky., may have found what we're all looking for. If you would like to submit a post to Clearing the Fog, please contact us here.What? I can just take a bus to a happy new year?

No diets, no yoga, no therapy, no counseling?

I found you do have to be careful though, about where you want to go. This destination rotates with, say, “18th and Broadway.” If you get on when it says “18th and Broadway,” you end up at, well, 18th and Broadway. That may be OK if that’s what you want.

Ahh, but the bus to Happy. Catch it if you can.

Where should you get off, you say?

Indeed. But don’t you know?

Published on January 24, 2021 14:45

January 17, 2021

Rare Glimpses

Mary Marrs Board and David Caddell. Photo provided by Anne Simmons. Over this year of disruption and isolation and sorrow, I have heard many people say they intended to dedicate some of the time they were stuck at home to sorting through family photos. While I seem to have frittered away all those months with nothing to show for it, some of you apparently followed through.

Mary Marrs Board and David Caddell. Photo provided by Anne Simmons. Over this year of disruption and isolation and sorrow, I have heard many people say they intended to dedicate some of the time they were stuck at home to sorting through family photos. While I seem to have frittered away all those months with nothing to show for it, some of you apparently followed through.

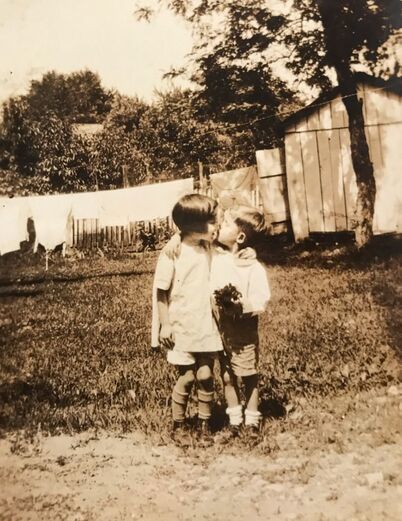

A week ago I was delighted to receive an unexpected text from a former classmate and old friend, Anne Moffett Simmons, who I hadn’t heard from in decades. Attached were photos that she and her sister had discovered while going through family albums.

One photo shows my mother, around age six, with her arm around the younger David Caddell, Anne's uncle, as he sneaks a kiss. In another photo, there's my mother sitting next to her friend Dot (Dorothy) Caddell, Anne’s mother and David's twin sister. David stands to the left, looking a little sheepish, and my mother’s cousin, George McWilliams Jr., is on the right, seemingly disinterested in all the commotion.

L-R: David Caddell, Mary Marrs Board, Dot Moffett, George McWilliams Jr., c1927. Photo provided by Anne Simmons.

L-R: David Caddell, Mary Marrs Board, Dot Moffett, George McWilliams Jr., c1927. Photo provided by Anne Simmons. I cannot explain the sheer joy that photo elicited. There was my mother, surrounded by her pals and playmates when she was a very young girl, holding what appears to be a bouquet of flowers. She’s smiling at the person taking the picture, whom she seems to completely trust to capture her pleasure in the moment. Dot looks like she can barely tolerate sitting still for these ridiculous shenanigans and is already plotting her next move. The boys stand as unwilling sentinels on either side.

It’s only since I began working on Next Train Out that I have become more fully cognizant of the depth of sadness my mother endured in her lifetime. The loss of her husband in mid-life was just the final blow. There had been the loss of two children and her mother while she was hundreds of miles away from family. The permanent absence of her father who had never bothered to contact her after disappearing shortly after she was born. And, after returning to her hometown to raise her two daughters, the eventual recognition that her old friends had largely moved on with their lives.

While I can recall moments when my mother laughed or acted a little silly, those were few. By the time I was old enough to pay attention, she seemed more commonly somber and somewhat melancholy. It has taken me a lifetime to reflect on why that was.

But in this photo she radiates happiness. Happiness to be seated beside her friend Dot. Happiness that she's the focus of someone's attention. Happiness that someone wants to take her picture. I wish I could ask that little girl what she’s thinking.

As you come across family photos while sorting through the detritus of your rich and complicated lives, I encourage you to consider who else might relish a glimpse into the moments captured by the camera. Because our connections with others have been so restricted over the past year, many of us are aching for a little time with those we love. You might be surprised how healing it can be to have your emotions stirred, even by a black-and-white photo from a time long ago.

Published on January 17, 2021 11:10

January 12, 2021

A Banner Year

Ed Lawrence found the Thin Blue Line flags at the Capitol insurrection on January 6, 2021, the most troubling. According to Wikipedia, the phrase “typically refers to the concept of the police as the line which keeps society from descending into violent chaos.” Ed Lawrence, of Frankfort, Ky., shares his response to the images of January 6, 2021. If you would like to submit a post to Clearing the Fog, please contact us here.

Ed Lawrence found the Thin Blue Line flags at the Capitol insurrection on January 6, 2021, the most troubling. According to Wikipedia, the phrase “typically refers to the concept of the police as the line which keeps society from descending into violent chaos.” Ed Lawrence, of Frankfort, Ky., shares his response to the images of January 6, 2021. If you would like to submit a post to Clearing the Fog, please contact us here.In the wake of last Wednesday’s events, my preferred media outlets have been spewing a lot of powerful words (also words related to power) like tyranny, sedition, rebellion, revolution, coup, conspiracy, and insurrection. I felt like insurrection might be the right word to describe the mob effect of that day in our history. I asked my Google Home device for a definition. “Violent uprising against a government or authority” seemed to me to best fit the bill for my perception of what happened.

As I watched the video clips of the insurrection over and over again, I started focusing on the flags waving in the air. In 2020 I took a class in visual rhetoric and so I began doing an amateur rhetorical analysis on the flags carried by the insurrectionists.

Of course, there were many Trump flags, which would be natural given the person who incited the insurrection. I feel like those carrying those flags were self-appointed members of the Trump militia.

Those carrying the American flag clearly felt it was their patriotic duty to bring back an America that only exists in their imaginations. A country that is solely white, Christian, and English speaking.

I noticed a couple of state flags: Florida and New Mexico to be precise. Were there Arizona, Georgia, and Pennsylvania flags? I can only suppose the carriers were making a case for states’ rights.

Media personalities kept saying the insurrection was surreal. My response to that was that they had never dropped acid. The insurrection was real, not surreal. Then I saw the huge flag bearing the name JESUS in bold letters. Is Jesus really prepared to run our government? I mean no disrespect to Jesus or to Christians of any stripe, but why was Jesus represented at the insurrection? The Jesus flag did seem surreal.

And then there was the Confederate flag in the Capitol. I understand why most people in this country were incensed by the sight. But for me, I travel the backroads of Kentucky making landscape photographs and come across Confederate flags so often, I’m numbed to outrage.

The flag that has me outraged is the flag of the Thin Blue Line. Why did I spot several policemen’s flags at the insurrection? Were police really in attendance trying to overthrow our government? I thought police take an oath to serve and protect, not riot and insurrect.

Today, the breaking news is that many Capitol police aided and abetted in the insurrection. Troubling indeed, but I still think about local police who were there. And with that thought, how many of them were complicit in the murder of Black citizens of our country? I’m generally not one for retribution, but I hope those carrying the flag of the Thin Blue Line are found and banished from policing forever.

Published on January 12, 2021 10:50

January 6, 2021

The long road ahead

Will 2021 offer us renewed hope? Photo by Rick Showalter. I already didn’t much like 2021. My dog had been mysteriously ill for days, not eating, never moving off the sofa. A buck mistook the side of my moving car for a toreador’s cape. I longed to talk to friends who were struggling with impossible family situations, but understood that they didn’t need my meddling.

Will 2021 offer us renewed hope? Photo by Rick Showalter. I already didn’t much like 2021. My dog had been mysteriously ill for days, not eating, never moving off the sofa. A buck mistook the side of my moving car for a toreador’s cape. I longed to talk to friends who were struggling with impossible family situations, but understood that they didn’t need my meddling.I was stressed.

And that was before the insurrection that has roiled our U.S. Capitol building since early afternoon. Today, our president incited mob violence that spilled into our halls of governance, where Republican members of Congress were arguing that an election certified by all 50 states was fraudulent. A woman who was shot has died. Our elected officials were whisked to bunkers or barricaded in offices. As evening falls, some of the mob has dispersed, but officers of the law are still working to secure the area.

Our nation is even more broken than most of us can grasp. It will not be fixed in 2021. It will take patient, united efforts from government officials and citizens alike over a very long time.

Meanwhile, the coronavirus rages on. Yesterday we once again recorded the highest number of deaths and hospitalizations since the beginning of the pandemic. Over the holidays, friends and relatives across the country avoided family members rather than gathering in quiet celebration. Some couldn’t hold the hand of an aged parent. Couldn’t race to the emergency room with a spouse. Had to initiate difficult conversations via phone.

Here in Kentucky the damp gloom seems to have settled permanently over our lives. 35 degrees. Drizzling. Without end. I have found myself sapped of all purpose, feeling helpless amid the continuing horror.

Then, as the drama unfolded at the U.S. Capitol, we learned that Georgia voters had successfully finished the job that we voters in Kentucky couldn’t: breaking Mitch McConnell’s grip on the U.S. Senate.

Glory be, they did it.

They did it despite ongoing voter suppression in Georgia. They did it thanks to an enormous commitment by a dedicated few to register new voters and trumpet the importance of these elections.

In November 1872, Samuel [George] Hawkins, a Black Kentuckian working to register voters in Fayette and Jessamine counties, was accosted by a mob of white men associated with the Ku Klux Klan. Hawkins, his wife, and his daughter were all taken from their home and murdered by the mob, leaving behind six younger children.* Newspaper accounts vary as to whether their executions were by hanging or by drowning. Whatever the grisly tactics, white Democrats weren’t going to allow Black Republicans to “steal” the election from their candidate, New York newspaper publisher Horace Greely. Despite their efforts, incumbent Republican President Ulysses S. Grant won.

In November 1900, three men in Bourbon County, Ky., carried out a scheme on behalf of the local Democratic party that lured Black men into games of craps. Over 60 Black participants were then arrested and jailed long enough to prevent them from voting in the November 6 presidential election.** The Republican won anyway, when incumbent President William McKinley defeated his Democratic challenger, William Jennings Bryan.

And in 2021, despite newly creative efforts at voter suppression—including, perhaps, allowing a pandemic to race unchecked through minority communities—the voices again could not be extinguished. They could not be hidden under a bushel. The people have spoken.

Amid the shocking images we have watched today, perhaps there are still glimmers of the hope that we are all searching for in 2021. The sun is still hiding, but if our nation can navigate the next 14 days, perhaps we can finally shift course. We can try something different. Perhaps this year we can try compassion, humility, and respect while serving others.

Earlier today, I foolishly imagined that might be enough. Tonight, I’m clinging to the idea that this change in leadership may at least present a first step toward gluing together the shattered pieces this administration will leave behind. *George C. Wright, Racial Violence in Kentucky, 1865-1940: Lynchings, Mob Rule, and “Legal Lynchings,” Louisiana State University Press, 1990, p. 51.

**“Conspiracy to Oppress and Injure the Negroes,” Morning Herald (Lexington, Ky.), November 2, 1900.

Published on January 06, 2021 18:07