Sallie Showalter's Blog, page 6

May 11, 2021

Life Without End

[image error]Philip on his new trail horse, October 2020. Philip Cullen was irrepressible.

If he wasn’t racing, he was volunteering at a race. Or officiating. If he wasn’t focusing on triathlons, he was fooling around with trail running or Ride & Tie events—at least until an unfamiliar horse got the better of him last spring. So Maureen gave him his own horse when he retired this past fall so they could trail ride together.

At triathlons, he usually attached a stuffed animal to the front of his bicycle just to give all the serious racers around him a laugh. He was good, and I imagine the sight of Philip passing with a stuffed tiger on his bike gave his competition motivation to pass him later. He didn’t care. He trained with discipline and he wanted to race well for the Irish National Team, but the focus was always on fun.

What surprised me most about Philip was the volunteering he did. He always volunteered to work the polls on voting day. He volunteered at every area triathlon he did not participate in. He helped coordinate training tris. He led the Tri Club. In just the last six months, I know that he volunteered to get jabbed in the J&J COVID vaccine trial back in November; volunteered to help with traffic and statistics at COVID testing sites; volunteered with the Red Cross assessing flood damage to homes in Eastern Kentucky this spring; and volunteered at the Big Turtle race in Morehead, Ky., in April, where he had planned to complete a 50K trail run before those niggling chest pains caught his attention and finally sent him to the doctor the day before.

Philip's wife, Maureen, took this photo as he headed to his last day of work at Lexmark. And, of course, it was only recently that Philip stopped working. He used to come out to our place after work, swim a mile and a half, have a beer, and then participate in a conference call with colleagues in the Philippines on my back patio before heading home. That’s when he didn’t have to be in China or Cebu handling business.

Philip's wife, Maureen, took this photo as he headed to his last day of work at Lexmark. And, of course, it was only recently that Philip stopped working. He used to come out to our place after work, swim a mile and a half, have a beer, and then participate in a conference call with colleagues in the Philippines on my back patio before heading home. That’s when he didn’t have to be in China or Cebu handling business.

Evenings when work wasn’t pressing, he might have a couple of beers and then start storytelling in his fading Irish brogue. I used to worry that his long stories might disturb the neighbors. But I expect they were laughing along with us.

Philip had tales of killer kites in India or the heat in Singapore. His years at the rival engineering school in Louisville. His frequent trips back to Ireland and the family he discovered there.

And we cannot forget his devotion to his family. He usually called me when he was on I-64 heading to Louisville to see his dad (and his mum before she died in 2018) or on I-75 to Ohio to see Maureen’s family. He was always there for them, whether helping address health issues or celebrating holidays or simply offering a helping hand.

In short, his heart was bigger than most. It gleefully carried a bigger load than most. It worked at a superhuman pace for sixty full years. No wonder it needed a rest.

Philip, you got more out of life than most of us ever dream of. You brought laughter and encouragement to the rest of us. You overcame injuries that might have beaten down a mere mortal. But nothing stopped you. You went full bore all the time.

The lucky among us only get nine lives. You used up every last one of them.

Rest in peace, my friend. Philip's tri bike he had custom painted in 2020 in anticipation of a retirement full of races.

Philip's tri bike he had custom painted in 2020 in anticipation of a retirement full of races.

If he wasn’t racing, he was volunteering at a race. Or officiating. If he wasn’t focusing on triathlons, he was fooling around with trail running or Ride & Tie events—at least until an unfamiliar horse got the better of him last spring. So Maureen gave him his own horse when he retired this past fall so they could trail ride together.

At triathlons, he usually attached a stuffed animal to the front of his bicycle just to give all the serious racers around him a laugh. He was good, and I imagine the sight of Philip passing with a stuffed tiger on his bike gave his competition motivation to pass him later. He didn’t care. He trained with discipline and he wanted to race well for the Irish National Team, but the focus was always on fun.

What surprised me most about Philip was the volunteering he did. He always volunteered to work the polls on voting day. He volunteered at every area triathlon he did not participate in. He helped coordinate training tris. He led the Tri Club. In just the last six months, I know that he volunteered to get jabbed in the J&J COVID vaccine trial back in November; volunteered to help with traffic and statistics at COVID testing sites; volunteered with the Red Cross assessing flood damage to homes in Eastern Kentucky this spring; and volunteered at the Big Turtle race in Morehead, Ky., in April, where he had planned to complete a 50K trail run before those niggling chest pains caught his attention and finally sent him to the doctor the day before.

Philip's wife, Maureen, took this photo as he headed to his last day of work at Lexmark. And, of course, it was only recently that Philip stopped working. He used to come out to our place after work, swim a mile and a half, have a beer, and then participate in a conference call with colleagues in the Philippines on my back patio before heading home. That’s when he didn’t have to be in China or Cebu handling business.

Philip's wife, Maureen, took this photo as he headed to his last day of work at Lexmark. And, of course, it was only recently that Philip stopped working. He used to come out to our place after work, swim a mile and a half, have a beer, and then participate in a conference call with colleagues in the Philippines on my back patio before heading home. That’s when he didn’t have to be in China or Cebu handling business.Evenings when work wasn’t pressing, he might have a couple of beers and then start storytelling in his fading Irish brogue. I used to worry that his long stories might disturb the neighbors. But I expect they were laughing along with us.

Philip had tales of killer kites in India or the heat in Singapore. His years at the rival engineering school in Louisville. His frequent trips back to Ireland and the family he discovered there.

And we cannot forget his devotion to his family. He usually called me when he was on I-64 heading to Louisville to see his dad (and his mum before she died in 2018) or on I-75 to Ohio to see Maureen’s family. He was always there for them, whether helping address health issues or celebrating holidays or simply offering a helping hand.

In short, his heart was bigger than most. It gleefully carried a bigger load than most. It worked at a superhuman pace for sixty full years. No wonder it needed a rest.

Philip, you got more out of life than most of us ever dream of. You brought laughter and encouragement to the rest of us. You overcame injuries that might have beaten down a mere mortal. But nothing stopped you. You went full bore all the time.

The lucky among us only get nine lives. You used up every last one of them.

Rest in peace, my friend.

Philip's tri bike he had custom painted in 2020 in anticipation of a retirement full of races.

Philip's tri bike he had custom painted in 2020 in anticipation of a retirement full of races.

Published on May 11, 2021 10:47

May 9, 2021

Silent Tribute

My mother, Mary Marrs Goodlett, in the center; my mother-in-law, Jean Showalter, on the right; and my brother-in-law’s mother-in-law, the inimitable Woody Mountz, on the left. Photo c1990 in Paris, Ky. I tend to ignore Mother’s Day. My mother has been gone 30 years. My mother-in-law has been gone just shy of 10. I’m not a mother. For me, Mother’s Day has become a nearly guaranteed quiet day with no obligations, because everyone else is engaged with family and special tributes to the mothers in their lives. And I have come to enjoy it for just that reason.

My mother, Mary Marrs Goodlett, in the center; my mother-in-law, Jean Showalter, on the right; and my brother-in-law’s mother-in-law, the inimitable Woody Mountz, on the left. Photo c1990 in Paris, Ky. I tend to ignore Mother’s Day. My mother has been gone 30 years. My mother-in-law has been gone just shy of 10. I’m not a mother. For me, Mother’s Day has become a nearly guaranteed quiet day with no obligations, because everyone else is engaged with family and special tributes to the mothers in their lives. And I have come to enjoy it for just that reason.This morning, however, historian Heather Cox Richardson, in her Letters from an American, wrote:

“Those of us who are truly lucky have more than one mother. They are the cool aunts, the elderly ladies, the family friends, even the mentors who whip us into shape.”

I, too, had “mothers” other than the one who birthed me. I considered my Aunt Charleen my second mother. My mother’s cousin, Ann McWilliams, always included us in family gatherings during the holidays and made us feel special. When I was in college, one of my piano teachers, Mimi McClellan, invited me to stay in her home one summer while I worked nearby. Each of these women, and many others, offered different perspectives on how to live life, how to embrace family, and what is truly important. I don’t remember having conversations about any of these things. I just watched them. And I pocketed the treasures offered by their examples.

All of these ladies are now gone, too. I have to look to my own generation—or the ones that have followed—for role models. I imagine I can still learn a thing or two from my friends and my neighbors and my relatives who demonstrate compassion and generosity and the sort of joie de vivre that makes life worth living. I’m still trying to learn patience and acceptance and forgiveness—traits critical for all mothers, and the very traits I lack, probably in part because I never took on a maternal role. From the time my mother pulled me onto her lap when I was an out-of-control five-year-old and said, somewhat sarcastically, "I hope you have six just like you," I knew I never wanted to be a mother. And I never had any ambivalence about that.

In her letter, Richardson claimed she “had at least eight mothers.” She goes on to describe one, Sally Adams Bascom Augenstern, a strong-willed widow who had lived near Richardson in her youth. Being the eldest of six siblings, Augenstern had already done her share of child-rearing by the time she was an adult. Said Richardson, “I've never met a woman more determined never to be a mother, but I'm pretty sure that plan was one of the few things at which she failed.”

Today, for all you mothers who wittingly—or unwittingly—took on that important job, thank you. Those of us who lacked the courage are grateful for the burdens you bore with such grace. We are still watching, and we are still learning.

Published on May 09, 2021 14:43

April 29, 2021

The Still Waters

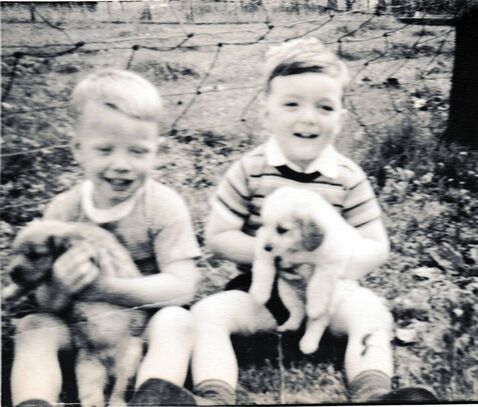

Sweetpea and Sluggo (Sandy Goodlett and Davy Fallis). Only two children appear in

The Last Resort

, my dad’s 1943 Salt River journal: Sweetpea and Sluggo. The affectionate nicknames Pud had for his first two nephews tell you everything.

Sweetpea and Sluggo (Sandy Goodlett and Davy Fallis). Only two children appear in

The Last Resort

, my dad’s 1943 Salt River journal: Sweetpea and Sluggo. The affectionate nicknames Pud had for his first two nephews tell you everything.In March 2018, I memorialized Sluggo, aka Dave Fallis, the elder son of my dad’s sister Virginia Fallis, when he died after a long illness. Today, I honor Sweetpea, aka Robert Dudley “Sandy” Goodlett, the first son of my dad’s brother Billy Goodlett, who died unexpectedly Monday after a brief illness.

When David Hoefer, the co-editor of The Last Resort, suggested that we annotate many of the personal and historical references in the journal to provide a more fulsome picture of Pud’s world, I knew we had some work to do. David researched most of the historical and technical details. I started digging up information about Pud’s family circumstances and his Lawrenceburg friends.

The first person I called was Sandy. He was the Goodlett family historian, and he had sustained ties to Lawrenceburg longer than the rest of us. David and I met with Sandy in his office in the building I still think of as the old post office, and we peppered him with questions. He was able to answer most of them, and I think he reveled in being a critical informant for our project.

Soon I realized I wanted to make a trip to the Atlanta area to talk to a couple of the “boys” who used to join my dad at his Salt River camp: my cousin John Allen Moore and Lawrenceburg native Bill “Rinky” Routt. Sandy said, “Let’s go.” We picked a date and Sandy drove me and our cousin Bob Goodlett to Atlanta and back. During that trip, we were also fortunate to spend some time with John Allen’s younger brother, Joe Moore, and with Lawrenceburg natives Eugene Waterfill and Mary Dowling Byrne.

It was a magical trip. And Sandy made it happen. Today, of all my dad's family and friends we visited, only Joe Moore survives.

L-R: Joe Moore, Bland Byrne, William "Rinky" Routt, Sandy Goodlett, Mary Dowling Byrne, Bob Goodlett, Eugene Waterfill, Sallie Goodlett Showalter. At the Buckhead Diner in Atlanta, 2015. Sandy was always unselfish with his time and his wisdom. If I planned a family gathering, I knew he’d be there. In his van, we discovered we could talk for eight straight hours and still learn something new.

L-R: Joe Moore, Bland Byrne, William "Rinky" Routt, Sandy Goodlett, Mary Dowling Byrne, Bob Goodlett, Eugene Waterfill, Sallie Goodlett Showalter. At the Buckhead Diner in Atlanta, 2015. Sandy was always unselfish with his time and his wisdom. If I planned a family gathering, I knew he’d be there. In his van, we discovered we could talk for eight straight hours and still learn something new. When Sandy died, I lost not only a beloved cousin and my go-to guy for all Goodlett family questions. I lost one more connection to the father I never really knew.

I’ve laughed this week with some family about Sandy’s rare equanimity and quietude in times of crisis and distress. That is not a typical Goodlett trait. Most of us are hard-headed and opinionated and high-tempered. We are intense and hard driving. Sandy kept his intelligence and his passion quietly under wraps. And when he offered us a glimpse, it was usually accompanied by that inimitable grin.

If we want to honor Sandy, we should all strive to approach life’s vicissitudes with his calmness and acceptance. We should strive to be as kind and caring as he was. And we should strive to love our family half as much as he did.

Read Sandy's obituary.

Published on April 29, 2021 12:36

April 25, 2021

More Skulduggery

The old Iowa State Penitentiary. Bob Patrick, of Berea, Ky., a retired attorney of unquestionable probity, reveals a little skulduggery that shaped his family history. If you would like to submit a post to Clearing the Fog, please contact us here.

The old Iowa State Penitentiary. Bob Patrick, of Berea, Ky., a retired attorney of unquestionable probity, reveals a little skulduggery that shaped his family history. If you would like to submit a post to Clearing the Fog, please contact us here.My father grew up in far northwest Iowa, where the family had moved after the Civil War. Apparently Indiana was simply too crowded. During the Depression, my Dad and his older brother would hunt rabbits and other game for food.

My grandfather was a bookkeeper in a local business and about the time my Dad started high school, my grandfather was arrested for embezzlement. I'm not certain of the amount, but it earned my grandfather several years in the Iowa Penitentiary in Ft. Madison.

So the entire family—my grandmother, three sons, and one daughter—moved to Ft. Madison, in the southeastern corner of the state. My grandfather, in addition to his peculiar accounting skills, had experience in farming. He became a trustee, taking care of chickens and living on the prison farm, making family visits easier. It was during this period that my father met my mother, both attending the Ft. Madison High School.

My father and his older brother went on to the University of Iowa in Iowa City, ultimately to dental school and medical school, respectively. When my grandfather was released from prison, he and the rest of his family also moved to Iowa City, where my grandfather took a job at a local savings and loan.

During my uncle's final year in medical school, my grandfather was caught stealing money from the savings and loan where he was employed. The bank president said he would not press charges if: (a) my grandfather left the state, and (b) the money was repaid. My uncle had just gotten a position with a medical practice in Taft, Calif., and my grandfather and grandmother joined him there. At the beginning of WW II, Taft, a desert community, was about as barren as northwest Iowa, so there was a fit. My Dad and his brother were able to repay the money.

Almost 30 years later, I married the granddaughter of the president of that savings and loan. He and his wife were at several Christmas dinners I attended at my wife's parents. No one but he and I knew of this connection. To read about the family skulduggery that prompted this post, click here.

Published on April 25, 2021 09:30

April 20, 2021

Relief

On count 1: Guilty

On count 2: Guilty

On count 3: Guilty

And I sobbed.

I had been sitting in my backyard intending to read, but all I was really doing was staring at the electric pink blossoms still gripping the redbud trees and watching the wind ripple the water on the lake. I had a lot on my mind, so I never even cracked open the book.

When the clouds moved in, I got a little chilly so I went inside and absentmindedly turned on the news. I saw that a verdict in the Derek Chauvin case was expected momentarily, so I sat silent, my heart racing.

When the judge walked in the courtroom, my anxiety rose. I told myself I couldn’t expect these jurors to do what so few others had ever done before.

But they did. They found Officer Chauvin guilty, in the eyes of the courts, of murdering George Floyd.

I am not Black. I’m still trying to grasp the reality of systemic racism. I have never been followed by the police or interrogated for suspicious behavior. I have never lost a family member to police brutality. But I sobbed like a baby after Chauvin was convicted.

The last couple of weeks have been so difficult. First it was Daunte Wright. Then Adam Toledo. Multiple mass shootings.

Even for a privileged bystander, it never, never seems to end.

But today we got a little relief. A brief glimmer of hope that something, something could change. That justice was possible.

Many are telling us not to read too much into this one verdict. It doesn’t change the family’s grief. It doesn’t change the fact that more Black lives were taken by police today. It doesn’t diminish the fear some parents have each time their child leaves home. It doesn’t change the flagrant racism and hatred we continue to witness in our country.

But maybe this will help us find the strength to keep fighting for right. Perhaps it will prevent us from giving in to despair.

I am relieved. I am even a little hopeful. Perhaps Mr. Floyd has indeed changed the world.

Published on April 20, 2021 19:11

April 18, 2021

State of Denial

Cathy Eads, of Atlanta, Ga., questions her governor's support for the Election Integrity Act of 2021. If you would like to submit a post to Clearing the Fog, please contact us here.

Cathy Eads, of Atlanta, Ga., questions her governor's support for the Election Integrity Act of 2021. If you would like to submit a post to Clearing the Fog, please contact us here.“Are you a politician or does lying just run in your family?”

― Fannie Flagg, Fried Green Tomatoes at the Whistle Stop Cafe

“Everyone is entitled to his own opinion, but not to his own facts.”

― Daniel Patrick Moynihan

Oh, Brian Kemp, you never cease to disgust me with your strident attempts to misrepresent voter suppression as some sort of election protection. Let’s get one thing straight right off the bat: You are likely the governor of Georgia because you assumed the roles of both player and umpire in that political game. I know of no other instance, in a democracy, where the candidate has also been the officiant of the race. Even former Georgia Representative Karen Handel, who has her own record of supporting right wing policies that hurt a vast number of her constituents, resigned her position as Georgia Secretary of State to run for governor in 2010.

Maybe signing this legislation to limit access to voting is an attempt to show 45 that you really do believe the Big Lie—and get back into his better graces. After all, when you refused to reject Georgia’s results of the 2020 presidential race, 45 did threaten you specifically with retaliation during your upcoming re-election campaign. Honestly, Governor, I think you hurt yourself more than 45 ever could have by passing that Voter Suppression Law in a private signing while having Georgia House Representative Park Cannon unlawfully arrested for knocking on the door of the signing room. I mean, did you watch the cell phone video(s) of her arrest?

Don’t you know that the best way to motivate proud, hard-working people to sure as hell go out and do something they have a right to under the law is to try to tell them they can’t, or that you are gonna make it harder for them to do it? Oh yeah, you do, you are a gun rights supporter. Well, let’s just say you and Georgia’s Republican state legislators have motivated the weary opposing team more than any half time Super Bowl coach’s pep talk ever could. I’m willing to bet that you’ve moved some of your moderate supporters to switch sides to save democracy as we know it, imperfect as it is. Georgia’s new Voter Suppression Law has pushed voter protection, and hopefully passage of H.R. 1, the For The People Act, to the forefront of federal legislative priorities for pro-democracy Congress members. So, thank you for that!

Governor, please stop referring to voter suppression laws as a means of ensuring election integrity. This idea is built on The Big Lie and it’s an insult to your intelligent constituents. It’s a show of your desperation to hold on to power, and of your lack of personal integrity.

Published on April 18, 2021 15:30

April 11, 2021

The Human Scale

Tessa Bishop Hoggard has written a compelling book about the people and events surrounding one of the more than 350 extrajudicial lynchings in Kentucky. On May 25, 2020, Derek Chauvin, a white Minneapolis police officer in his mid-40s, evidently decided that 46-year-old George Floyd’s alleged infraction of passing a counterfeit twenty-dollar bill should cost him his life. Three other officers watched as Chauvin kept his knee on Floyd’s neck for 9 minutes and 29 seconds—even longer than we had originally understood.

Tessa Bishop Hoggard has written a compelling book about the people and events surrounding one of the more than 350 extrajudicial lynchings in Kentucky. On May 25, 2020, Derek Chauvin, a white Minneapolis police officer in his mid-40s, evidently decided that 46-year-old George Floyd’s alleged infraction of passing a counterfeit twenty-dollar bill should cost him his life. Three other officers watched as Chauvin kept his knee on Floyd’s neck for 9 minutes and 29 seconds—even longer than we had originally understood. Despite exhortations from the other officers and the citizens standing nearby, despite Floyd’s pleas to let him breathe and his invocation of his recently deceased mother, Chauvin kept his knee on Floyd’s neck until he was no longer breathing. And then he kept his knee on his neck for another three and a half minutes.

Chauvin’s defense attorneys have posed a number of counterarguments during the initial days of the trial, including that Floyd had illicit drugs in his system, that he had a heart condition that contributed to his death, and that his physical size made him a threat to the officers even after he was handcuffed and lying face down on the ground.

Over the past 10 months we have learned a bit more about George Floyd and his family. We know he was a college athlete who struggled to stay in school and struggled with addiction. He spent some time in prison. We know he had moved from Houston to Minneapolis to try to turn his life around. During the trial, we saw his fiancée describe his kindness when he had first approached her at the Salvation Army where he was working security. For months we have witnessed the courage and the oratory and the passion of Floyd’s siblings and his cousins. We’ve seen the confusion of his bright-eyed young daughter whose father is now famous.

He has come to feel like someone we knew, like someone we might encounter joking around at a corner market just like Cup Foods.

That’s what Tessa Bishop Hoggard has accomplished in her book In the Courthouse’s Shadow. Through diligent research, she has fleshed out the story of one heretofore anonymous young Black man who was lynched in Paris, Ky., in 1901 after being accused of a minor crime. Like George Floyd, George Carter had previously run afoul of the law but was trying to settle down with his young family and build a good life. Like Floyd, Carter never had a chance to claim his innocence or plead his case. A group of white men with power in his community decided that he should pay with his life for a crime that we have no evidence ever even occurred.

We also learn that others who endured a fate similar to Carter’s were described in the press the same way, whether accurate or not: “burly negroes over 200 pounds.” As in Floyd’s case, physical size—or perceived physical size—justified illegal actions.

In Hoggard’s book, we learn about Carter’s family, their hopes and their dreams, and what happened to them after he was killed. We learn the fate of his two young daughters. We also learn about the family of the white woman who identified him as the man who had assaulted her, a crime that was originally reported as an attempted purse snatching. We learn about the fate of her eight-year-old son, who witnessed the assault and helped the sheriff identify Carter as the assailant.

We learn that George Carter, like George Floyd, was a father, a son, a brother—a human being. He was not just a statistic of early 20th-century racial injustice. Just as George Floyd was not merely another victim of 21st-century police brutality.

This is a problem our nation obviously has not solved. On March 18, during a House Judiciary Committee hearing on anti-Asian American violence and discrimination, Republican Congressman Chip Roy of Texas said, “We believe in justice. There are old sayings in Texas about find all the rope in Texas and get a tall oak tree. We take justice very seriously. And we ought to do that. Round up the bad guys. That's what we believe." Afterwards Roy refused to apologize for his choice of words and doubled down on the language.

As columnist Charles Blow recently wrote in the New York Times: “It is hard not to draw the through-line from a noose on the neck to a knee on the neck. And it is also hard not to recall that few people were ever punished for lynchings. Motionless Black bodies have been the tableau upon which the American story has unfolded…”

Those who witnessed George Floyd’s murder have testified about their sense of helplessness at the time and the enormous guilt they still carry. Some videotaped the crime and shared it with the world in horror. Those who discovered George Carter’s body hanging in front of the courthouse on that cold February morning tarried at the scene and took photos, seemingly proud of the town’s latest trophy and the message it sent.

Is that a sign of some progress in the last 120 years? Are we finally beginning to push back on these unforgivable acts of oppression and subjugation? What would we do if we found ourselves witnesses to such a crime? Would we simply stand by and watch, as the two doormen in New York recently chose to do as a 65-year-old Asian American woman was being assaulted on the sidewalk in front of their building? Or would we find the power to act?

In 1901, George Carter was only 21 years old when he was lynched. I wonder if he, in his final moments, silently called for his mother. Murky Press is proud to offer In the Courthouse’s Shadow: The Lynching of George Carter in Paris, Kentucky through Amazon or by contacting Murky Press directly here. We encourage you to recommend the book to others or post a brief review on Amazon to help spread the word.

Published on April 11, 2021 09:20

April 4, 2021

The value of a human life

An elementary school bulletin board celebrating International Night, which includes the slogan “We all smile in the same language.” Cathy Eads, of Atlanta, Ga., reflects on her experience raising a family in a multi-cultural community. If you would like to submit a post to Clearing the Fog, please contact us here.

An elementary school bulletin board celebrating International Night, which includes the slogan “We all smile in the same language.” Cathy Eads, of Atlanta, Ga., reflects on her experience raising a family in a multi-cultural community. If you would like to submit a post to Clearing the Fog, please contact us here.Daoyou Feng was 44 when she was shot and killed in the Asian hate crime spree in Atlanta on March 16. According to The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, she had only been working in the spa a few weeks when she was murdered. She was a Chinese citizen with no known family in the United States and no family able to travel to the U.S. to bury her. She was one of six Asian American women out of a total of eight victims shot to death during the multi-site killings.

For 17 years I lived in a suburb of Atlanta that has a very large Asian and Indian population. My children had friends, classmates, and neighbors from Pakistan, India, South Korea, and Japan. Their elementary school displayed the flags from the countries of students’ families. The technicolor array of banners encircled the entire cafeteria. The PTA staged an international night each spring that included a smorgasbord of delicious authentic dishes lovingly prepared by many of these families. Warm friendly smiles animated their faces as they proudly served up, and showed off, the delicacies of their home lands. The high school had a similar event that featured native dress, dances, and other performing and cultural arts.

When my son entered college at the University of Kentucky, he said, “Mom, it just feels a little weird being around so many white people all the time.”

When my daughter was young, I co-led a 12-member Girl Scout Troop with a mix of Asian, Indian, and Caucasian girls. They were as varied in personality and temperament as any group of girls could be—because they were all individuals, of course, not just because they had ancestry from different continents.

Moving to Georgia from Kentucky, I’m glad fate drew us to our particular neighborhood so my family got to know, and appreciate, the richness of many cultures, and to work, learn, and socialize with people from so many different backgrounds. Whether they were from Houston or Hyderabad, Seoul or South Carolina, we are better humans for knowing them.

Just like I’m sure there are people who are better humans for knowing Daoyou Feng.

Can we stop hate that’s planted and nurtured in dehumanizing otherness? Can we find a way to instill in every heart and mind that human beings are all, first and foremost, fellow human beings—all valuable, all equally entitled to live life with respect and dignity?

I haven’t given up hope that we can cultivate compassion for all of humanity. Impossible as it may seem, I also believe that we must. I guess the most important question is, how?

Published on April 04, 2021 18:49

March 31, 2021

Oh the Madness!

A photo op with the gracious Artis Gilmore at the 2018 Kentucky Book Fair. My name is Sallie, and I am a basketball fanatic.

A photo op with the gracious Artis Gilmore at the 2018 Kentucky Book Fair. My name is Sallie, and I am a basketball fanatic.I blame my mother. About the time I was entering my early teens, I recall how surprised I was to find my serious, book-reading mother occasionally watching University of Kentucky basketball games on TV. I don’t remember her talking about basketball much, but she had taken me to a few high school games, where my cousins starred. Up until that point, though, I hadn’t thought of her as someone who watched sports on television. At the time, I was devoted to Wide World of Sports and broadcasts of the Olympic games, but no one in my household was a fan of professional sports. I couldn’t imagine how my mother had the patience for such a tedious, and to me at the time boring, pursuit.

But I took notice. Basketball was not frivolous. Her interest had given it a certain heft.

When I was in college, UK won a national championship. Shortly afterward, so did the University of Louisville. My interest was piqued again. When home for the holidays, I watched what games were available. I started developing loyalties and interest in the players.

By the time I went to graduate school in Chapel Hill, N.C., I was hooked. While there, UNC and N.C. State won championships. I adored Jim Valvano. Some guy with an unpronounceable name had just started coaching at nearby Duke, trying to pull that team up from the bottom of the heap. Michael Jordan, Sam Perkins, Matt Doherty, and Brad Daugherty wandered in and out of the foreign languages building where I taught. I was mesmerized.

Settling back in Kentucky after school, there was almost no way to avoid full basketball fanaticism. It was all around me. It was what I had in common with the majority of people I encountered. Some were suspicious of me because I rooted for both UK and UofL. But I was a pure college basketball fan. If a team was on TV and the players had signs of talent, I was interested. I was awed by their athleticism. By their tenacity. By their skill.

If you know me at all, you’ve probably heard me say, “God gave Kentuckians basketball to help us through our dark, dreary winters.” Why else would the typical college basketball season begin when the time changes in November and end in April, just as we’re all busting to get back outside?

Some of my friends still have trouble reconciling that someone who loves a good book and a classical music concert also loves college basketball. Thankfully, I have a handful of cousins who are just as diverse in their interests as I am. During this strange basketball season and the unexpectedly exciting men’s NCAA tournament, my cousins and I have connected from our homes in two different (rival) states. It’s been sheer delight watching their take on the games: the scientist who’s crunching the stats in real-time; the former player who’s questioning the coach’s call or the offensive set; the UofL and IU grad who’s trying to remain loyal to his alma maters and the Big Ten while honoring his Kentucky roots; and me, the simple-minded humanist who’s interested in the characters and the drama that’s playing out on the floor. While my cousins are breaking down plays, I’m texting “Woohoo! What a pass.” I don’t see the intricacies of the game; but I do see effort, determination, teamwork, and joy.

Another basketball season is about to end. I have a favorite team in the Final Four whose players unexpectedly earned my love and devotion only a month ago. The two teams I followed all season never even made it into the tournament. Initially I thought that meant I’d have a March free to do other things, but I surprised even myself. I adapted. I watched the games because I find beauty in the athletes’ ability. It makes me happy. And these days, that’s the only reason I need to invest some time in front of the TV. P.S. Before you ask, of course I’m an equally avid fan of the women’s game! I’ll pull for our SEC arch-rival South Carolina in the Final Four, even though it hurts just a bit.

Published on March 31, 2021 11:12

March 19, 2021

Is This Freedom?

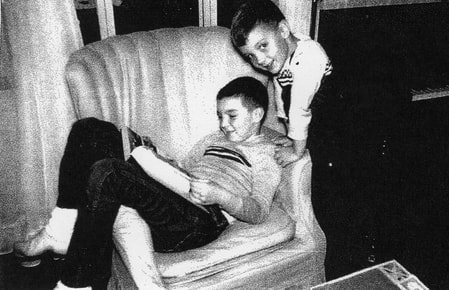

Vince Fallis, mugging for the camera, while his older brother, Dave, lounges in the chair. Vince Fallis, of Rabbit Hash, Ky., recalls a previous nationwide vaccination effort. If you would like to submit a post to Clearing the Fog, please contact us here.

Vince Fallis, mugging for the camera, while his older brother, Dave, lounges in the chair. Vince Fallis, of Rabbit Hash, Ky., recalls a previous nationwide vaccination effort. If you would like to submit a post to Clearing the Fog, please contact us here.On March 9, I received my second dose of the Pfizer vaccine at a well-organized assembly line managed by St. Elizabeth Medical Center, also known as The Empire around these parts. I was in the old folks group because I am one. Everyone seemed eager, yet somewhat reserved, as we went through the process. I profusely thanked the vaccinator, since I understand most are volunteers. I think we should have a parade for them when this is over (if it is ever over).

I felt somewhat elated as I drove away. Barbara and I will now be able to see the granddaughters. That has not happened since last fall. Excruciating.

The whole experience also brought back the memory of a day in 1955 when I stood with my parents, Leonard and Virginia, and my brother, Dave, in a long line outside Beechwood School to receive the Salk vaccine. I knew very little about polio but remember seeing on our black-and-white TV the images of dreary, hopeless hospital wards filled with iron lungs with only the heads of the pitiful victims visible.

In our minds the polio vaccine was a miracle that would keep us from the fate of those we saw in those terrifying hospital scenes. However, as an 8-year-old standing in that line, I was experiencing what I would now recognize as an approach-avoidance conflict. Some years before I had undergone the painful series of rabies shots after a dog bite, and I wasn’t sure how closely this vaccination would match up to that somewhat traumatic memory. But I survived, and we were thrilled to do our part to eliminate the dreaded virus. Drs. Salk and later Sabin became national heroes.

Fast forward to the present day. With over 550,000 of our fellow Americans already struck down by the novel coronavirus, many of my surviving fellow citizens have now made shunning the vaccine an emblem of personal freedom, tribal politics, or general disbelief in science. Substantial numbers of adults—many with higher education and, I must assume, a reasonable level of intelligence—have chosen to decline the vaccine.

Barbara recently said that if polio threatened us today, it would not be eradicated. I agree. Perhaps more disturbing is our total inability to come together for the common good. We see other acts of humanity: volunteers handing out boxes of food to long lines of people who have lost their livelihood during the pandemic; donors generously opening their wallets to help those in areas stricken by natural disasters; yellow-vested volunteers walking through Chinatown to deter criminals who are attacking people of Asian descent. Many choose to participate in these acts of compassion, but protecting each other from a deadly virus is, for some, a bridge too far.

I’m coming close to going off the rails, but I must say one more thing. We should all be outraged when we see white males wearing clothing displaying Nazi images. My uncle, John C. Goodlett, the father of my dear cousin, Sallie Showalter, walked through one of the death camps during World War II. We have a handwritten letter in which he describes the experience. I often wonder how he did not see those images every night when he was trying to sleep.

This country yearns for a new call to the real meaning of Patriotism, not one based in hate and exclusion, but one that lifts us up by working for the common good of everyone in this country. Will this happen? You may be skeptical. But I remain the eternal optimist. Peace be with you.

Published on March 19, 2021 16:11