Sallie Showalter's Blog, page 10

June 27, 2020

Atonement

I’m going to meet George Carter’s great-great-nephew.

I’m going to meet George Carter’s great-great-nephew.Even if you’ve read Next Train Out, the name George Carter may not ring a bell. My calculations indicate that I called his name five times in the narrative, but I’ve learned over recent weeks that I probably should have cited his name more.

George Carter is significant to Lyons’ story, and he’s significant to today’s story. In this era of reckoning—and, one hopes, some sort of reconciliation, eventually—the George Carters of the world need to be remembered. We cannot forget. And those of us whose ancestors are directly tied to these stories, we need to face the music. Now.

Next month I will sit down with a descendent of the man who was lynched in front of the Bourbon County courthouse because he allegedly “assaulted” my great-grandmother.

I’m not sure how to relay to you the awe I’m feeling, the anticipation, the relief, the gratitude, and, yes, the shame that shivers up my spine as I contemplate this meeting.

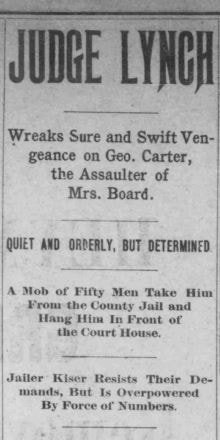

I won’t detail the machinations that resulted in the heinous act on February 10, 1901. I will say that the single news story about the initial incident, which occurred in early December 1900, described what we today would call an attempted purse snatching.

But perhaps it’s important to keep in mind that the newspaper where that article appeared, the Kentuckian Citizen, was published by Mrs. Board’s cousin. The newspaper’s offices occupied a building once owned by Mrs. Board’s father, a prominent physician. After her father’s death, Mrs. Board inherited that property. One of the competing papers in town, the Bourbon News—which carried a fulsome story of the lynching two months later—was published by the husband of Mrs. Board’s closest friend.

I point that out to show how the power structure in town was stacked against Mr. Carter. Whatever transpired between him and Mrs. Board, he didn’t stand a chance. He was black. She was white, and she was connected. Two months after the incident, when the mob formed, whatever had actually happened on that cold December day was long forgotten. Rumors and innuendo and wild imagination had successfully altered the truth. For some in town, the crime now justified taking the life of a young man with a two-year-old daughter.

Sound familiar?

We have an opportunity to address some of this ongoing injustice now. Our country is awake. Video recordings provide unshakable truth. We must find the courage and the determination to start fixing these inequalities and addressing the resulting brutality.

I am grateful that I will have the opportunity to speak to one of Mr. Carter’s descendants. I am grateful that he wants to meet with me. I have no idea what I will say. There is no recompense. I cannot change the past. But I’m eager to see what I can start doing today.

Published on June 27, 2020 18:54

June 6, 2020

A Night in Pale Armor

The Minneapolis 3rd Police Precinct is set on fire. Photo by CARLOS GONZALEZ, Minneapolis Star Tribune, May 28, 2020. Tim Cooper, of St. Paul, Minn., shares his experiences living in the Twin Cities in the aftermath of George Floyd’s death. If you would like to share your thoughts on Clearing the Fog, please contact us here.

The Minneapolis 3rd Police Precinct is set on fire. Photo by CARLOS GONZALEZ, Minneapolis Star Tribune, May 28, 2020. Tim Cooper, of St. Paul, Minn., shares his experiences living in the Twin Cities in the aftermath of George Floyd’s death. If you would like to share your thoughts on Clearing the Fog, please contact us here. Your eyes open to the sound of gunfire, a pitched battle on the far periphery of your being. The shots—staccato, syncopated—lay siege and surround you in fear. Immediately you wonder, do you flee or do you surrender? Do you hold firm or do you seek shelter? Where could you go? To whom or to what would you capitulate?

And then you realize that distant roads have been reopened, that the sound you hear is nothing more than semis on the faraway interstate rebounding over undulations in the road. Why have you never heard this before? Is it the silence of the recent curfew, of inertia, of comfortable isolation, that awakens you to a noise that was always there?

But this fear, this pervasive fear—how do you account for it? You remember two days previous, unthinking as you take your dog for her normal 5 a.m. walk. Ah, the comfort of your routine, your beloved sense of order. Behind you, flashing lights from a police cruiser as you trek down the deserted street. When he pulls up beside you the policeman wearily reminds you of the curfew’s hours, suggests staying closer to home. He attempts a comforting smile but doesn’t receive one from you in return. Later, you’re simply grateful that he didn’t turn the siren on full-blare. The thought of being physically accosted and harmed by him had never occurred to you.

And why not?

Because you have armor that shields you even as you defy your city’s curfew. You are white, male, middle-class, educated, not tall, not overly muscular—in short, not a threat. You’re not black, brown, yellow, or red; you’re not a recent immigrant; your speech sounds local. Without this armor, would you have been gently prodded to return quietly to your home? Recent events tell you no.

Your beloved city is on fire, and you can measure the anger and trepidation everywhere you go. There is a despair that permeates, that is all-encompassing. Drug stores, gas stations, grocery stores, banks are boarded up and closed. You drive across the state line to Wisconsin to put gas in your car. A branch of your bank is there and you can get medication from a pharmacy. The grocery stores appear well-stocked. You carry on with the charade of normalcy.

But you know better.

You recall that you also live in a time of pandemic, that participation in demonstrations of solidarity for George Floyd and for those without power or voice involve calculated risk. You do the arithmetic, and it still demands that you participate, that to do less than all you can will result in an amputated life of insidious horror—for you and for others.

Solace is an ephemeral commodity. You try to comfort your friends—both near and far—and they do the same for you. You try to galvanize them to political action, and you plot strategies of engagement. You want desperately to affect change.

And then you recall that June 6 is the anniversary of Robert Kennedy’s assassination. Bobby, killed advocating for change, killed because he believed in the power of existential action, killed because he cared. You consult his speech in Indianapolis on the night of Martin Luther King’s murder, a speech that always comforts and calms you. And Bobby, quoting the Greek poet Aeschylus, said:

Even in our sleep, pain which cannot forget

falls drop by drop upon the heart,

until, in our own despair,

against our will,

comes wisdom

through the awful grace of God.

Published on June 06, 2020 17:59

June 4, 2020

More Thoughts on “Our Sins”

Joe Ford, of Louisville, Ky., responds to a recent blog post—and to our times. If you would like to share your thoughts on Clearing the Fog, please contact us here.

Joe Ford, of Louisville, Ky., responds to a recent blog post—and to our times. If you would like to share your thoughts on Clearing the Fog, please contact us here.Just three weeks before her death on August 5, 2019, I attended a showing of the documentary film Toni Morrison: The Pieces I Am at the Speed Museum Cinema in Louisville. Frankly, I had not read any of her works and knew next to nothing about her—I attended only after prodding from my wife, who consumes books at a prodigious rate and had read a couple of Morrison’s books. A wonderful film, if you get the chance.

The documentary spent some time, not surprisingly, on Beloved, for which Morrison won the Pulitzer Prize in 1988. The novel is based on a true story—that of Margaret Garner, a slave for the Gaines family of Maplewood plantation, Boone County, Kentucky.

In January of 1856, during the coldest winter in 60 years, the Ohio River froze over. A pregnant Margaret, her husband, Robert, and their four children as well as eleven others crossed the river just west of Covington, Kentucky, and made their way to Cincinnati, then split up to avoid detection. Nine slaves made it to safe houses and eventually to Canada via the Underground Railroad.

Margaret, Robert, their children and Robert’s father and his wife made it to the residence of Margaret’s uncle, west of Cincinnati. Her uncle went to the abolitionist Levi Coffin for advice on how to get them to safety. Before her uncle returned with that advice, however, slave catchers and U.S. Marshalls first surrounded and then stormed the house. Though Ohio was a free state, the federal Fugitive Slave Law allowed return of slaves to their owners if caught in another state.

Realizing that they would be captured and returned to slavery, Margaret killed her two-year-old daughter and wounded her other children, preparing to kill them and herself before she was stopped.

And this is where I cried.

There is first the almost inconceivable pain and anguish of a mother who would kill her children to save them from a life of slavery, suffering and brutality. Infanticide was not unknown for this very reason.

But the legal ramifications about the case gained the most attention: would the Garners be tried for murder, which meant they would be tried as persons (and that their daughter was a person)? Or would they be treated as property to be returned to their masters? That is, is the issue murder or the destruction of private property? Property won, and they were returned to Kentucky and a life of bitterness, despair and abuse as slaves.

Somehow this juxtaposition of human despair and societal degradation affected me profoundly; it wasn’t so much a change of opinion as a change of degree and a recognition of the cultural structure that supported slavery, free state or not. All pretense fell away. There is no confederate monument that should still stand. There is no argument about fidelity to preservation of a “culture.” There is only evil masquerading as something else, only another inexplicable example of man’s inhumanity to man. If we fly the Confederate flag (and my nephews do) we show our ignorance, and we say that rape, torture and forced labor are fond traditions, sort of like Thanksgiving at grandma’s.

This is our legacy. It is how we got here. You tell me: is the despair gone? Is the degradation any less structural?

So, no, in response to the question at the beginning of “Our Sins,” I don’t know when the outrage ends. But I, too, believe the looting will obscure the reason for the protests. We’ll follow our sad excuse of a president and concentrate energy and focus on the looting and completely lose sight of why there is so much anger. And we will feel justified to dismiss the true cause, because, you know, property is more valuable and more important than human lives. Legacy indeed.

Certainly we have to transform ourselves first. And then our words and actions.

Yes, we agree with the business owners whose neighborhoods have been looted or burned. It’s wrong. And, yes, we care about our police officers, many of whom have behaved in truly brave and Christian fashion during this unrest. But we have to speak to them and to others of what the protests are about. Black men are routinely killed, often by police. It is not right. Have that conversation. Speak up! The death of our fellow citizens, like George Floyd, should not happen in America. You don’t die for (allegedly, since there was no trial) trying to buy a pack of cigarettes with a $20 counterfeit bill. Keep the conversation focused on that.

We need to care. Because it is the right thing to do. And because next it will be our sons and daughters, compliant after an arrest, after a mistake, or after a march for justice. Will they deserve to die?

Published on June 04, 2020 12:46

May 30, 2020

Our Sins

A headline from The Bourbon News, February 12, 1901 This week our dark times got darker.

A headline from The Bourbon News, February 12, 1901 This week our dark times got darker.Over the month of May—still sheltered in place or cautiously emerging into society while simultaneously mourning the 100,000 Americans who have died from COVID-19—we have learned of three American citizens killed, needlessly, inexplicably, by police or those assuming law enforcement duties. All the victims were black. All the perpetrators were white.

Will this outrage never end?

The rage incited by these events has engulfed our cities. Protestors have blanketed the streets. Some agitators have destroyed property, burning and looting businesses with no association to the injustice. A response that initially felt rational now feels insane.

In the midst of all this horror, another related story caught my attention. On Monday in Central Park, a 57-year-old birder asked a woman walking in the wooded Ramble area to leash her dog, as the area requires. She refused. As he calmly offers the dog treats in an effort to convince her to control her dog, she accuses him of threatening her and says she will call the police. With that, he takes out his phone and begins to record the incident. The woman, who is white, then calls 911 and tells the dispatcher, in an increasingly hysterical voice, that she is being threatened by an African American man. (CNN story)

We all know of famous incidents in our nation’s history where a false accusation from a white woman cost a black man his life. But how many others, never reported or denied by those in power, stain our past? Today we’re finding that an immediately accessible recording device may be the only way for the black victim to get justice, even if it’s posthumously.

In the Central Park instance, which thankfully did not go that far, the man and the woman actually have a lot in common. They’re both sophisticated New York City dwellers who take advantage of the beauty of Central Park. They’re both highly educated—he at Harvard, she at the University of Chicago. They’re both successful in their fields. They even share the same last name (although they are not related).

But Amy Cooper felt that her whiteness gave her tremendous power over Christian Cooper. And she decided to use that power. If he had not recorded their interaction, she very well may have succeeded in having him arrested for a fabricated crime. And convicted. Because of his skin color.

As I worked on Next Train Out, I had to wrestle with my own family’s story of a white woman’s alleged assault leading to a black man’s death. The only information I have about the incident is what was reported in the local and national newspapers, during a time when purple prose and editorializing were evidently acceptable. None of the news articles offers any details that might indicate that what happened should have been a capital crime.

The only witness was an eight-year-old boy, my grandfather. In my fictional telling of the story, I chose to assign him the natural empathy and compassion of a human innocent, someone not yet indoctrinated into the mores of his community’s power brokers.

Over our long and tortured history, I suppose we humans have always sought to subjugate others. To demonstrate power through domination. To cover up weakness by claiming the upper hand.

At risk of repeating a tired refrain, this has to end. We must stop snuffing out the lives of others simply because we deem ourselves superior. The color of our skin does not grant us that privilege. We have to be better.

Published on May 30, 2020 20:17

May 17, 2020

Peering happily into the abyss

I have never considered myself creative. I’m a dogged rule-follower. I can read music but couldn’t improvise if you put a gun to my head. I can follow a recipe but rarely experiment in the kitchen. I could never dream up a clever Halloween costume, and I eventually came to hate a holiday that I had loved as a child because of it.

I have never considered myself creative. I’m a dogged rule-follower. I can read music but couldn’t improvise if you put a gun to my head. I can follow a recipe but rarely experiment in the kitchen. I could never dream up a clever Halloween costume, and I eventually came to hate a holiday that I had loved as a child because of it.I have absolutely no artistic ability: I can’t draw or paint or sculpt. I have no interest in or talent for what some might call crafts, including scrapbooking or photo collages or needlework of any type. In fact, in high school I tested in the bottom tenth percentile in spatial aptitude. So much for a career as an architect.

But recently my cousin Charley shared an article that made me rethink my capacity for being creative. In fact, it made me realize that it may well have been my bent toward creative thinking that hounded me throughout my sketchy professional career. For me, every problem was simply a puzzle to be solved. What I didn’t understand was that solutions that seemed obvious to me were perhaps unimaginable to others. Was it my fearlessness, my ability to envision a positive outcome, my willingness to tackle something new in unexpected ways that frequently made my co-workers so ill-at-ease?

In the article “Secrets of the Creative Brain” (The Atlantic, July/August 2014), Nancy C. Andreasen shares the results of decades of research into some of the great creative geniuses of our times, both in the arts and the sciences. Some of these individuals’ common characteristics may not be surprising, but they hit home for me. For example, she found her subjects were “adventuresome and exploratory,” and they were willing to take risks. Check. She added that “Creative people tend to be very persistent, even when confronted with skepticism or rejection.” Check again. Once I’ve decided something is possible and laid out a plan for getting there, I don’t back down. I’m heading to the finish line, whether you’re coming with me or not.

Andreasen also relays that many creative people have broad interests across many disciplines, and they are good at making unexpected connections. That, for me, is the essence of good writing—connecting disparate things in surprising ways, using language or metaphor to awaken the reader’s senses. I’ve always been interested in lots of subjects, but I know little about any of them. In a typical day I bop from immersing myself in politics to paddling on the lake and admiring the wildlife to researching a technical computer issue to reading a novel about World War II to trying to understand a poem that a friend has shared with me to romping with the dogs in my neighborhood. I hate routine. I love variety. I never want to do the same thing twice. In graduate school, my department chair railed against "dilettantes," declaring he would have none in his classes. I would laugh and wonder, “What else are we?”

I recall sitting in fiction writing classes recently and wondering how on earth writers come up with the story lines and the scenes and the conflicts and the dialogue necessary to create a compelling narrative. Up to that point, everything I had ever written had been based on facts, whether I was preparing a technical manual or promoting an art event or writing a faculty member’s bio.

I’ve come to realize that what I sorely lack is imagination. Not creativity. Many have asked me about the subject of my next novel. I swear that I’m a “one-and-doner.” Starting with the realities of a person’s life let me cheat the first time. How could I possibly invent a story and a plot and the characters whole-cloth? I simply don’t have the capacity to do that.

But perhaps I will begin to think of myself as creative. I recognize that I tend to look at things a little differently than others. I am fearless. I don’t mind choosing the untrodden path. I embrace making choices that might bewilder others. I might even propose outlandish courses of action. Sometimes they work. Sometimes they don’t. But nothing will hold me back if I think I have a shot at accomplishing it.

Published on May 17, 2020 19:16

May 10, 2020

As We Pause

A brilliant redbud, before May’s freezing temps. What a strange spring. What a strange year.

A brilliant redbud, before May’s freezing temps. What a strange spring. What a strange year.During the winter months, I’m not sure we had five nights when the temperature dipped below freezing. Here, in the middle of May, we’re trying to make up for it.

I noticed this morning that the leaves in the tops of my redbud trees and tulip poplars are black and crumpled. I’m reading that this will not damage the trees, but after one of the most beautiful redbud blooming seasons that I can remember, it’s hard to see the trees’ new leaves suffer in the cold.

It’s May 10, and we have yet to see any goslings or ducklings on the lake. This seems unusually late, but I remain hopeful as I continue to see Mallard and Canada Geese pairs waddling around the neighborhood. And there is a large bird, perhaps a Blue Jay, sitting in a nest just beyond my office window, so some natural spring activity is taking place.

Recently I’ve noticed a lot of birds I don’t usually see: a Red-headed Woodpecker, an Eastern Kingbird, a Scarlet Tanager pair, a Yellow-rumped or Myrtle Warbler with its three astonishing yellow patches. We also seem to have plentiful Tree Swallows, Barn Swallows, Red-winged Blackbirds, Bluebirds, and Killdeer, despite the acres and acres of woodlands that have been turned into muddy deserts here in our neighborhood. Do I have more time to look for them this year, or are they moving into territories where they haven’t always been as plentiful?

The whole world seems upside down to us right now, of course. Nothing seems normal. I guess it’s no surprise that even Mother Nature seems a little off. Perhaps as I acknowledge the usual harbingers of spring, the sheer ordinariness of those events will nudge us toward a more unremarkable time.

Occasionally I have wondered aloud whether the novel coronavirus isn’t Mother Nature’s way of resetting the balance. Few can seriously argue that we haven’t wreaked havoc on this world that nurtures us. Our sheer numbers strain the earth’s resources. And the planet doesn’t need humans to sustain its ecosystems. Without our presence, other predators would pick up our load, or illnesses like chronic wasting disease would run through animal populations, thinning the herd. Much like COVID-19 appears set on thinning ours.

As this pandemic has forced us to put many human activities on pause, nature has been busy reversing the deleterious effects of our obsession with productivity. Around the world, water is cleaner, air is purer, animals such as sea turtles have nested without human interference. In just a few short months, nature has begun to reclaim its domain.

Sitting comfortably in my home, I can’t ignore that this is occurring amid massive human suffering from an unstoppable virus that has stolen hundreds of thousands of lives and destroyed economies. The long-range effects of this pandemic, both human and otherwise, cannot yet be imagined. If the human race is to survive, we must, and we will, apply our scientific knowledge toward finding a way to exist with this virus in our midst.

But while we’re focused on that critical task, can we not also recognize the value of adjusting our impact on this earth so we eventually live as grateful recipients of its abundance, rather than as relentless destroyers of the gifts it has to offer?

Published on May 10, 2020 13:43

April 28, 2020

Creating a Scene

A spring cove on our lake. A few days after this photo was taken, there were two types of purple wildflowers and one yellow blooming boldly on the forest floor. I could not name any of them. Did I really see them? Recently I wrote that I now have two books in my “catalog.” As I worked on the second book, it frequently occurred to me what strange bedfellows they are: a first-person narrative by a still innocent 19-year-old naturalist driven to document the flora and fauna inhabiting his halcyon getaway; and an almost gritty tale of a man stripped of his innocence who leaves his home behind and wanders from one commercial/industrial area to another with hardly a nod to the natural world around him.

A spring cove on our lake. A few days after this photo was taken, there were two types of purple wildflowers and one yellow blooming boldly on the forest floor. I could not name any of them. Did I really see them? Recently I wrote that I now have two books in my “catalog.” As I worked on the second book, it frequently occurred to me what strange bedfellows they are: a first-person narrative by a still innocent 19-year-old naturalist driven to document the flora and fauna inhabiting his halcyon getaway; and an almost gritty tale of a man stripped of his innocence who leaves his home behind and wanders from one commercial/industrial area to another with hardly a nod to the natural world around him.I love to spend time outdoors, and I sometimes feel ill-at-ease in the city. I am the daughter of a naturalist, a scientist who could identify any specimen he encountered during an amble through the woods. I, however, was never disciplined enough to fully develop his prodigious skills. While I can identify many native woodland trees and common birds, the names of most wildflowers, grasses, and garden plants are a mystery to me. And I truly regret that I can’t recognize bird songs.

For years I was certain that that shortcoming alone disqualified me from writing a novel. Successful fiction is full of lush details of blooming flowers and the bees hovering around them. Or a prairie of grass and the animals that live there. Or a midnight sky and the constellations that awe us.

In “Seeing the World Around Us,” I mused about the importance of being able to name a thing for that thing to fully enter our consciousness. Without that ability, we are blind. We look past the diversity of life all around us. We come to consider ourselves the all-important foreground spotlighted against an indistinguishable background.

I still believe that my deficiency seriously weakens my ability to provide the sensory details readers need to feel a place. The plants and critters who share our space define our world, perhaps even define a part of who we are, even if we can’t always recognize them.

So when I had a story I just had to share with others, and a fictional narrative seemed the only way to tell it, perhaps I was fortunate that that tale largely unfolded in cities or confining indoor spaces—steamy kitchens, tiny apartments, the birthing bedroom. I stole a few opportunities to place my characters outside in the fresh air. In retrospect, it’s clear that my characters, like their creator, look outdoors when they are seeking balm for a troubled soul, or a place for reflection.

I was reminded of my inability to fulsomely describe a lush plein air scene as I read a recent article in Smithsonian magazine, sent to me by my cousin Barbara, about an acclaimed “naturalist, novelist, photographer and movie producer” whose name I had never encountered: Gene Stratton-Porter, born Geneva Grace Stratton in Wabash County, Indiana, in 1863. Perhaps I’m showing my woeful education by admitting I was not familiar with her, since both Rachel Carson and Annie Dillard cite her as a keen influence.

I have not read any of her work—fiction, nonfiction, or poetry—but I can only imagine the richness of the natural scenes she portrayed. Her intimate knowledge of the Limberlost wilderness she wrote about, gained during countless days exploring on horseback and waiting quietly for the perfect photo, must make her tales of plucky young girls and strong women come alive.

Stratton-Porter evidently brought to her writing both my father’s ability to document the natural world and my desire to tell a personal story. She had both the scientist’s eye and the writer’s imagination. In addition, she had the patience of a photographer, willing to devote the time needed to capture the most arresting photo, and then to indulge in the careful writing necessary to relay that vivid image, and her human response to it, in words.

Amid all her talents, Stratton-Porter most relished her simple sensory responses to the world she discovered while wandering outdoors:

“Whenever I come across a scientist plying his trade I am always so happy and content to be merely a nature-lover, satisfied with what I can see, hear, and record with my cameras.”

I, too, am a nature-lover, not an academic or a trained naturalist. As life seems to slow for all of us, perhaps this is the time I need to devote to not only admiring but learning to name the beautiful things that catch my eye and restore my soul.

The author of the Smithsonian article, Kathryn Aalto—a landscape historian and garden designer, as well as an author of several books—is herself a master at describing natural detail. Her first paragraph immerses the reader in northeastern Indiana’s Loblolly Marsh Nature Preserve, a small part of the vast swamplands that Stratton-Porter spent her life documenting:

The author of the Smithsonian article, Kathryn Aalto—a landscape historian and garden designer, as well as an author of several books—is herself a master at describing natural detail. Her first paragraph immerses the reader in northeastern Indiana’s Loblolly Marsh Nature Preserve, a small part of the vast swamplands that Stratton-Porter spent her life documenting:“Yellow sprays of prairie dock bob overhead in the September morning light. More than ten feet tall, with a central taproot reaching even deeper underground, this plant, with its elephant-ear leaves the texture of sandpaper, makes me feel tipsy and small, like Alice in Wonderland.” Stratton-Porter also recognized early the danger of mankind’s desire to tame the land for our own use. As Aalto writes:

“Twenty years before the Dust Bowl of the 1930s, Stratton-Porter forewarned that rainfall would be affected by the destruction of forests and swamps. Conservationists such as John Muir had linked deforestation to erosion, but she linked it to climate change:

“It was Thoreau who in writing of the destruction of the forests exclaimed, ‘Thank heaven they cannot cut down the clouds.’ Aye, but they can!...If men in their greed cut forests that preserve and distill moisture, clear fields, take the shelter of trees from creeks and rivers until they evaporate, and drain the water from swamps so that they can be cleared and cultivated, they prevent vapor from rising. And if it does not rise, it cannot fall. Man can change and is changing the forces of nature. Man can cut down the clouds.”

Published on April 28, 2020 19:29

April 19, 2020

Family Secrets

My family, circa 1960. I am on the far left. Did they know what danger I presented to them? Nobel Prize-winning writer Czeslaw Milosz is often quoted as saying, “When a writer is born into a family, the family is finished.”

My family, circa 1960. I am on the far left. Did they know what danger I presented to them? Nobel Prize-winning writer Czeslaw Milosz is often quoted as saying, “When a writer is born into a family, the family is finished.” I stumbled across this quote recently when reading about the one-woman play based on Elizabeth Strout’s novel My Name is Lucy Barton that opened earlier this year in New York. I chuckled. As I have pursued publishing two books about family members—one about my father who died when I was seven, and the other about my maternal grandfather whom my mother never knew—I have frequently wondered about the propriety or even the dangers of writing about family.

In my case, I did not set out to write a “tell all” book or to reveal any uncomfortable truths about my personal experiences.

In The Last Resort, I essentially let my father do the talking, and I was cautious not to include in the excerpts from his Harvard Forest journal any details that I thought might be construed as too personal or too negative toward those in his orbit. Nonetheless, I did want to reveal just enough to make him feel more fully human to readers.

Next Train Out is, of course, a novel. It is a fictionalized telling of my grandfather’s life. I relied on the facts I had at hand to discern possible motivations or character traits that would lead him to take the actions he did. Some may consider the details of the story scandalous or horrifying. I simply view them as the facts.

Nearly all the people who populate these books are long gone from this earth. That distance gave me some comfort and perhaps the license to share these stories. At the same time, I felt some responsibility for making my representation of the characters as truthful as I could, given the limitations of my knowledge. I would sometimes ask myself, “If Effie Mae’s descendants were to read this book and somehow recognize her in the telling, will they feel I have maligned her memory?” I don’t think so.

There is one character in Next Train Out who is portrayed as a sort of villain, which I don’t believe is truly accurate. But I needed a foil for Lyons, and he was a good choice. I checked with his great-grandsons—my cousins—twice to be sure they would be OK with my fictional representation. They assured me I didn’t need to worry.

Another cousin called recently to say how delighted she was to find her grandfather and other relatives identified by name in the novel. It made the whole story come alive for her. She probably didn’t remember that I had called her late last year to be sure she was OK with my using their real names. During that conversation, she offhandedly shared some physical and personality traits of those family members with me, which I dutifully incorporated into the story.

So it can indeed be dangerous to have a writer in the family. Or in your circle of friends. But, as Anne Lamott wrote in Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life:

“You own everything that happened to you. Tell your stories. If people wanted you to write warmly about them, they should have behaved better.”

Published on April 19, 2020 12:13

April 8, 2020

“one of me”

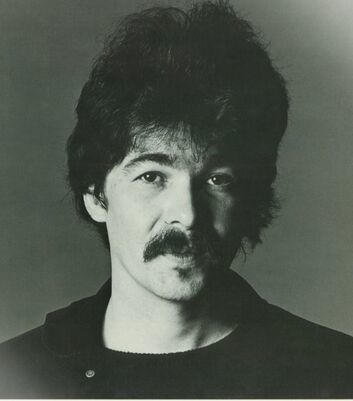

John Prine, from the Bruised Orange album cover. Charles Goodlett, of Zionsville, Ind., captures the sense of helplessness and grief so many of us are feeling as Covid-19 strikes our friends and our heroes. If you would like to submit a posting for Clearing the Fog, contact us here.

John Prine, from the Bruised Orange album cover. Charles Goodlett, of Zionsville, Ind., captures the sense of helplessness and grief so many of us are feeling as Covid-19 strikes our friends and our heroes. If you would like to submit a posting for Clearing the Fog, contact us here.We heard last night that John Prine succumbed to COVID-19 in Nashville, having been critically ill for at least a week. It shocked and saddened me and elicited a melancholic reflection back 50 years, reminding me how much his music, especially his first album in 1970, infused my entry into young adulthood.

When I was a senior in high school and just coming of age in the tumultuous era of Vietnam War protests, culture wars, Nixon, drugs, and the shock of assassinations, riots, Kent State, and paranoia, this album shed resonating light on the hardships of everyday people with humor, irony, and grit.

“Sam Stone” is a gut punch about the consequences of Vietnam combat, heroin addiction, and PTSD. The carefree pleasure of getting high and “just trying to have me some fun” was the theme of “Illegal Smile.” “Spanish Pipedream” described a deserting soldier's escapist dream. “Hello in There” offered an unforgettable immersion into the loneliness of growing old. And, of course, who can forget the mocking sarcasm directed at hypocritical Christian patriotism in the chorus of the song whose title is its first line:

But your flag decal won’t get you into Heaven anymore

They’re already overcrowded from your dirty little war

Now Jesus don’t like killin’, no matter what the reason’s for

And your flag decal won’t get you into Heaven anymore

"Six O’clock News" reminds us of the life story behind the shocking destruction of a young man. And then there's the anthem for all rebellious Kentuckians (and a rage against Mr. Peabody’s corporate environmental destruction well before anyone ever mentioned global warming), a favorite of so many, “Paradise”:

The coal company came with the world’s largest shovel

And they tortured the timber and stripped all the land

Well, they dug for their coal till the land was forsaken

Then they wrote it all down as the progress of man

Chorus

So Daddy, won’t ya take me back to Muhlenberg County,

Down by the Green River, where Paradise lay.

I’m sorry my son, but your too late in asking,

Mr. Peabody’s coal train done hauled it away.

Listen to my 6-minute tribute, featuring one of Prine's most frequently performed songs, “Angel from Montgomery.”

Prine was a singer-songwriter with a legendary cult following who served up folk tales of biting humor—all told in stories about people, the truth unvarnished with searing insights and hilarious wit. He captured life’s humor and made it more interesting and fun for all of us.

Perhaps the most hilariously ironic statement of independence in all of folk/rock is the first verse of “Sweet Revenge” from his album of the same name:

I got kicked off of Noah's Ark

I turn my cheek to unkind remarks

There was two of everything

But one of me

And when the rains came tumbling down

I held my breath and I stood my ground

And I watched that ship go sailing

Out to sea John, we are all mourning your death while poignantly celebrating your life by singing along with you one more time, with a tearful twinkle in our eyes. Benediction [offered by Sallie Showalter]

In late March, soon after the news broke of John Prine's diagnosis, my friend Peter Berres of Lexington, Ky., eloquent and sage writer about the Vietnam conflict, sent me a Prine performance of "Hello in There."

In Berres' words:

"Forty-five years of bringing, at least, a tear to my eye each and every time I listened (hundreds to thousands?). This seems like one of the most poignant performances, in my mind. I suppose it may have something to do with our times and situation.

Been watching this daily for several weeks. Now, with news of his diagnosis, watching has transformed into treasuring this performance, this song, this man..."

Published on April 08, 2020 09:30

March 30, 2020

Connecting in Isolation

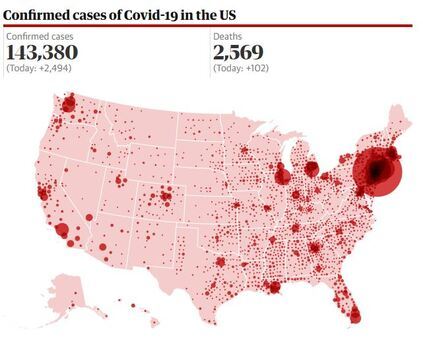

We’re all connected now. The coronavirus knows no borders. Data as of 30 Mar 10:25am EST. Source: Johns Hopkins CSSE. It occurred to me recently that I’ve already heard from people in six states who have read Next Train Out: New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Minnesota, North Carolina, Kentucky, and Florida. I know that individuals in Georgia, Ohio, and New York have ordered the book.

We’re all connected now. The coronavirus knows no borders. Data as of 30 Mar 10:25am EST. Source: Johns Hopkins CSSE. It occurred to me recently that I’ve already heard from people in six states who have read Next Train Out: New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Minnesota, North Carolina, Kentucky, and Florida. I know that individuals in Georgia, Ohio, and New York have ordered the book. I have been thinking of the book as a “regional” novel, perhaps because of its settings in Kentucky, Ohio, and the Maryland coast. So I’m pleased to see its reach extend to New England, the Upper Midwest prairie, and our nation’s southernmost state. Though I confess that all of these readers have some sort of connection to Kentucky—however tenuous—I want to believe nonetheless that my limited data indicate the book has a wide appeal.

That little survey of Next Train Out readers also made me realize that even during this period of social isolation we can share common experiences with far-flung friends and relatives, as well as people we’ve never met. I’ve delighted in the conversations and email exchanges I’ve had with those of you who have read the novel and have reached out to ask questions or offer critiques. We may not be able to meet for coffee or lunch, but we can still connect remotely and discuss something of interest to us both.

In a much broader sense, I’m reminded that, while we’re in isolation, reading affirms our affiliation with greater humanity. Reading prods us to feel profound human connections with the characters in a book, however dissimilar we believe they are to us. While this worldwide pandemic might force us to become more self-centered in our daily routines, reading coaxes us to imagine ourselves in someone else’s situation. Faced with that character’s challenges, how would we respond? What would we do? How would we feel?

In a time when the empathy of America’s citizens is once again being severely tested, it’s critically important that we look beyond our own perhaps small inconveniences and annoyances and consider the sacrifices and the heartaches of those around us. It’s impossible to turn on the television or check the news without seeing heart-wrenching stories of people who are ill, who have lost loved ones, who are tending to the medical needs of the sick without the necessary life-saving equipment, who are going to work every day to provide us with the goods and services that remain essential, who are struggling to patch together a precarious financial situation, who are wondering if the business they built will survive another month, who are fretting about their children’s education, who are struggling to stay healthy, both physically and mentally, during our voluntary home incarceration.

How equipped are we, individually, to acknowledge their struggles? Do we fully recognize the need to change our habits to possibly keep someone else safe? Are we willing to make those little sacrifices?

Reading widely helps train us for moments like these. It teaches us empathy. And compassion. It reminds us how small our own little world is. It reminds us that there are others with needs so much greater.

In a recent article in The New Yorker, Jill Lepore, a professor of history at Harvard, wrote: “Reading may be an infection, the mind of the writer seeping, unstoppable, into the mind of the reader. And it is also … an antidote, proven, unfailing, and exquisite.”

In order, potentially, to reach an even wider audience—to spread “the contagion of reading,” as Lepore describes it—I have now released a Kindle version of Next Train Out. If you or someone you know prefers to read books on a tablet, e-reader, or other device—whether for convenience or to easily enlarge the size of the text—the Kindle version might be a good choice. It’s also an economical option for those watching their budget during these uncertain times.

If you have read Next Train Out, I humbly ask you to consider writing a brief review of the book on Amazon. That may help other readers stumble across the title as they’re looking for a new diversion during our nationwide quarantine. I remain grateful for your interest.

Published on March 30, 2020 08:18