Allan Kelly's Blog, page 31

November 7, 2017

How much did it cost?

An interesting question came up at an event last week:

“My Kanban team has been asked by accounts to put a cost on each story that is done. How do I calculate this?”

My initial thought was: easy, and it is easy to give a simple answer to this question but if you unpack the question and the motivation behind it things get more interesting. Although the question was asked about a Kanban team most of the answer applies equally to Kanban, Scrum or Xanpan teams but contrasting the Kanban and Scrum approach offers an interesting insights.

So, first off the easy answer:

Select a period of work, say a month.

Count how many things (the things you want to know the cost of, stories, backlog items, tickets) got done (what ever your definition of done) during that period, e.g. 6 user stories might have been completed in the month.

Calculate the burn-rate for your team, e.g. if you have 5 team members who each cost $100,000 a year then the monthly burn-rate for the team is $41,666.

Divide your burn-rate by the number of items done, e.g. $41,666 / 6 = $6,940.

This approach adheres to the maxim “It is better to be roughly right than exactly wrong” – which is often credited to John Maynard Keynes but I believe it actually comes from philosopher Careth Read.

Although you might see many things potentially wrong with this crude calculation it has one redeeming feature: it is quick and therefore the cost of doing this calculation is low.

If you want you can improve on this calculation with more data. At the aggregate level you could consider a longer period with more items. Or you might calculate the statistical distribution and provide a range of answers.

Alternatively if you record the start and end dates of the work you could make this calculation more fine grained:

Work on an item starts on 1 November 2017 and completes on 6 November, 4 elapsed working days

The daily burn rate for the team is $1,923 per day (based on the same team of 5 and 260 working days per year)

Therefore a 4 day story cost: $7,692

Now notice, this figure is $700 higher than the previous figure. Which is the right answer?

As an engineer you want to know the actual figure, there should be an equation here, right?

Well yes, there should, but as with any equation you need to make some assumptions. Accountants know this, just ask them about “exceptional” items on the balance sheet and you will find out how subjective accounting is.

By the way, notice this second calculation is also fast and cheap. Were we to ask everyone who touched the story to record the time spent then two things would happen. Firstly those who recorded their time would be less productive in doing the work itself so the cost of knowing the cost would increase.

Second, you are replacing one set of assumptions with another. Namely: that people can accurately record or recall the time they spend doing something. They can’t, so the figure is subjective again, check out my Notes on Estimation and Retrospective Estimation if you don’t believe me.

Back to accounting…

Now the question that arises is “why even ask this question?” – surely recording costs at such a detailed level is waste itself? What value is knowing the cost of each small piece of work?

Now I agree with this, and I would hope you have a conversation with those asking the question as to what they are trying to achieve, what are they going to use this data for? – what they are going to use the data will influence how you calculate it.

But.

But, if you are leading a team and are approached by an accountant with the question “how much does each item cost?” I would advise you not to open the waste question there and then. My advice is to comply with their request in the most efficient manor, i.e. calculate it by one of the methods above.

Let me suggest that were you to immediately move to the question of “Why are you asking me this?” let alone “Answering your question is waste therefore I will ignore it” is likely to create more problems than it will solve.

For better to answer such questions, win some credit and trust then later return with the bigger questions. And since there are different ways to come up with a number you have an opportunity:

“Bill, you know those ticket costings I’ve been giving you for the last three months?”

“Sure, Betty, they are really useful for the capex/opex report.”

“Well Bill, I think there is a better way of calculating them can we talk about how you are using them?”

The fact that there is some ambiguity in the question and answer is an opportunity to have a discussion. First though, you need to win the right to have the discussion.

Now back to the original question.

The motivation behind the question was in part because Scrum teams assign estimates to stories and these estimates can be used as proxies for cost. In terms of accuracy such an approach is wild, at best it is little more than a random number generator for most teams and at worst it will distort both the estimate and the cost calculation. Numbers based on such estimates are unlikely to be accurate at all.

However the techniques described above will work just as well for a Scrum team as a Kanban team. You probably want to work at the Sprint level:

A team of five did 3 stories in a 2 week Sprint (10 working days)

Each team member costs $100,000 a year therefore each Sprint costs $20,000

Each story cost $6,666 ($20,000 / 3)

Such an approach is going to be far more accurate than anything based on estimates and probably more accurate than anything based on time recording. Again you could use more data to build up an even more accurate picture.

Now my big BUT…

This is all about COST.

Everything so far has been about cost. And I know most teams deal in cost. I know most of you are constantly asked “how much will it cost.”

But I also know there there is someone, somewhere, who will promise to do the same thing for less. While you are on the cost side of the equation you will always loose.

What we should be doing is considering Value. How much are these work items worth?

Rather, or in addition, to reporting cost you want to be reporting Value added:

“Bill, here are the figures from the last month, in total we did 10 items at a cost of $41,000 and we added $86,000 to sales”

Or maybe:

“Bill, here are the figures from the last month, in total we did 10 items at a cost of $41,000 and we added 1,000 site views”

“Bill, here are the figures from the last month, in total we did 10 items at a cost of $41,000 and we made 500 children smile”

I know measuring value is hard but we have to try. If nothing else, estimate value the same way you estimate effort.

Read more? Subscribe to my newsletter – free updates on blog post, insights, events and offers.

The post How much did it cost? appeared first on Allan Kelly Associates.

October 31, 2017

Kanban paradox

For a while now I’ve been seeing a paradox with Kanban. Specifically, Kanban compared to Scrum.

For a team new to Agile – although some regard this as heretical I place Kanban under the Agile umbrella, yes I know its more about Lean than Agile but of cause Agile is itself a Lean method, anyway…

For team, specifically a software team, looking to adopt a new process there is a choice:

Kanban has a very low barrier to entry, to get started Kanban essentially says “visualise your work and manage the result.” Starting Kanban can be as simple as putting up a board and tracking work items. In Kanban visualisation should drive improvement. Change can be incremental and gradual. Change is rooted in learning.

Scrum has a far higher barrier to entry: essentially Scrum says, “Adopt Sprints, designate a Product Owner, appoint a Scrum Master and build out a backlog.” Once these changes are done you can run with Scrum and then the Scrum Master and retrospectives will kick-in and drive further improvement.

Interestingly, neither method says explicitly “Improve your quality.” Yet I always believe a lot of the success of Agile methods is down to good old quality improvement: writing fewer bugs and having fewer bugs to fix means greater predictability and more time to deliver valuable software. But I digress.

It is easier to start with Kanban because it requires less up front change. However that does mean the improvements are slower coming.

Conversely, Scrum drops in, changes a lot and most teams see an immediate improvement. Scrum relies less on subsequent change.

Because Kanban relies more on ongoing change it is more difficult. It is easy to get stuck at the “we built a Kanban board so we are doing Kanban stage.” Change in Kanban requires one to see the need to change, understand what will fix a problem and then follow the change through. That often requires experience. Thus in teams adopting Kanban there is a greater need for a coach, a consultant, someone who has done it before.

Scrum on the other hand makes far more changes upfront and the recipe for improvement is more straight forward. And of cause there are a lot more books on Scrum, blogs on Scrum, Certified Scrum Masters and Scrum experience out there. So while it is harder to get started with Scrum (because more needs to change) there is less need for further change and you change does not require the same level of knowledge.

You see this specifically when you look at statistics. Watching the numbers should be important in both processes but with Kanban it is near essential. Anyone with real understanding of Kanban knows that queuing theory, lead times, possibly weighted lead times, and a bunch of other numbers need to be examined.

Scrum on the other hand doesn’t go much further than a burn-down chart. Yes, making more improvement with Scrum will also benefit from understanding lead times, queuing theory and the rest but you can quite happily use Scrum, and even improve Scrum, a fair bit without understanding these ideas.

So here is the paradox:

It is easier to start with Kanban than it is Scrum without expert knowledge, but it is harder to improve Kanban than Scrum without expert knowledge.

In many ways I prefer Kanban but I find this need for expert knowledge troubling. I suppose I shouldn’t, I’m a consultant, I am that expert, people hire me to help improve their Kanban processes so it does make more work for me.

In the longer run, the Kanban approach is more likely to lead to a genuine all inclusive culture of improvement and is less likely to get stuck in a sub-optimal position – yes Scrum fixes things, but is it the best fix possible?

Looked at like this gives me a new perspective on Xanpan.

I wanted Xanpan to be two things:

An understandable description of actually following an Agile process, specifically a Kanban/XP hybrid processes

An example of how, and why, teams should create their own processes.

The same paradox is here: Xanpan should be easy to start but allow you to improve; creating your own process requires a bit more knowledge that only really comes with experience.

To step back a minute and ask another question: What amount of change can a team handle to start with?

I find that I advocate more initial change than I used to. Because I’m fearful of creating a learned dependency I really want teams to learn to change and improve themselves. But… once a team has decided to change I want to seize the opportunity and install a bunch of changes while enthusiasm is there.

Read more? Subscribe to my newsletter – free updates on blog post, insights, events and offers.

The post Kanban paradox appeared first on Allan Kelly Associates.

October 27, 2017

Books update: User Stories, Continuous Digital and Project Myopia

Someone told me the other day “I can’t keep up with your books” – and you know what? I’m not surprised, it has been a busy couple of months for me on the books front but actually, there has been very little new writing – except with this blog.

First off, “Little Book of Requirements and User Stories” is now available in print.

This is a collection of pieces I wrote for Agile Connection a couple of years back which I compiled into an e-book. Sales of the e-book have been good, especially since I put it on Amazon and so, after a couple of request I’ve created a print version.

Right at the moment I’m amazed that Little Book is ranking as the 46th best seller in systems analysis and design which I think makes it a best seller!

The cheapest way to get the book is to buy thee-book on LeanPub. Amazon (all sites) have both print and ebook versions but they are more expensive. If you would like a copy for free please write me a review on Amazon UK and I’ll post you a copy – first six reviews only!

Next… Continuous Digital and Project Myopia….

Continuous Digital began life as #NoProjects, then Project Myopia, then became Continuous Digital. The name changes reflected the way my own thinking grew and changed. What began as a critique of the project model grew into an alternative model in its own right. In doing so it became something different, hence Continuous Digital.

But the more Continuous Digital stood alone the more the original chapters looked out of place. So I decided a few weeks ago to bundle them into their own book: Project Myopia.

I hope readers will find them complementary although I think they both stand alone. Both are only available as e-books on LeanPub, indeed there is an LeanPub bundle “Rethinking Projects” containing both. That said, right now Continuous Digital contains a coupon which allows readers to download Project Myopia for free. (It won’t be there for much longer.)

Splitting Continuous Digital in two has allowed me to race through my editing. There is still some work to do but content wise the book is pretty much done. It will remain a LeanPub only e-book for a little while longer and then…

Project Myopia would benefit from some more editing but I have no great plans to change it much. The changes I would make are all covered in Continuous Digital anyway.

Please, if you have any comments on any of these books, or suggestions to make them better let me know.

Read more? Subscribe to my newsletter – free updates on blog post, insights, events and offers.

The post Books update: User Stories, Continuous Digital and Project Myopia appeared first on Allan Kelly Associates.

October 24, 2017

The Solution defines the Problem

How many times have you encountered a user/customer/client who describes the thing they want in terms of Microsoft Excel? – “What I want is a macro in Excel to pick up all these data points and then…”

Many a Business Analyst has started from this point and worked back to discover what the clients real “problem” is. Quite possibly the client never considered themselves as having “a problem”. Quite possibly the “problem” would never have been spoken about it the client didn’t have an understanding of spreadsheet technology. And in the days before spreadsheets were invented the task may have been tiring, time consuming and prone to error but, thats just how it was.

Regardless of whether Excel is the solution they finally get, or not, it is only because they can imagine a solution that a problem can be defined. In fact, the Solution defines the Problem.

Excel is not the only example…

I was travelling on the London Underground the other day when this advert leapt out at me: “Estimated bills got you in a spin? Get accurate ones with a smart meter”. What?

Really, I mean: What?

I’ve been paying electricity, gas and other metered bills for over 20 years, not only have I never “got in a spin” about an estimated bill but I’ve never given it two thoughts. Neither can I ever recall anyone saying to me “Gee I hate estimated bills… they are so much hassle…”. OK, maybe some people have but so few that it hardly ranks as a world class problem.

Actually, now I think about it: I prefer estimated bills. It is hassle having a meter reader come to the door and having to show them the meters. And it is even more hassle reading my own meter, finding the box key, writing the reading down, trying to log into a website, doing “forgot my password” …

This advert, this whole product, is a great example of Solution Defines the Problem. Estimated bills are not a problem until you to have a solution.

Yes I know Solution defines Problem is hearsay to some. We are supposed to find the problem and work backwards from the problem to the solution, outside-in.

Yes I know that all you Business Analysts and Product Managers were trained – as I was myself – to look for the problem and then define a solution: a solution that might just happen to be technology based, and might just happen to be software.

And Yes I know to many of you the idea of a company creating “a problem” so they can then solve it is morally repugnant but… lets think about it for a minute.

What problem does the iPhone 8 solve? What was at the front of Apple’s hive-mind when they designed the iPhone 8?

And what problem does the iPhone 8 solve that the iPhone 7 didn’t solve? Or for that matter the iPhone 6? 5? 4?

(I mean “what customer problem”, one could argue the problem the iPhone 8 solves is Tim Cook’s need to have more sales revenue.)

Solving problems is not enough.

I’m not saying outside-in, problem first, innovation and development doesn’t work. Clearly such an approach has work in many cases. What I am saying is: it is not always appropriate; sometimes a more effective way of working is inside-out.

What can the technology do?

How can we make people’s lives better with this?

This approach too has a number of success stories. Rather than condemn it as “wrong” maybe we should be asking “When and where does it work?” and “Which approach is the most appropriate?”

When creating a new thing – be it software, hardware or services – our understanding of the problem evolves as our understanding of the possible solution, or solutions, evolve. One starts off thinking of a solution, or a problem, we seek to understand some more – maybe by building part of a solution or by talking to someone we think have the problem, we learn a little, maybe we continue in this mode or maybe we flip and work on the other side of the equation. And round we go again, iteration.

It is a learning cycle, the question is, what is the fastest way to learn?

I included the solution-problem hypothesis in my Agile Cambridge keynote last month. Afterwards I was e-mailed by someone whose email I’ve now lost (apologies!) and recommended a book: Overcrowded by Roberto Verganti.

Roberto Verganti, takes a similar but different approach to the same question. For him the key is: meaning. At first I wasn’t quite sure if “meaning” was the right word but as I’ve read more I think it is, albeit meaning in a fairly broad sense.

Verganti’s argument isn’t quite the same as mine but it is close enough, he is also arguing for starting with a solution and working backwards. For him the aim is to create new meaning, you might say that he identifies a generic problem “Humans needs more meaning in their world.”

Try the iPhone test in this context too: “What is the meaning of the iPhone 8?”

I’m going to be talking more about this in my keynote to TopConf in Tallin next month, in the meantime please let me know what you think. Madness?

Read more? Subscribe to my newsletter – free updates on blog post, insights, events and offers.

The post The Solution defines the Problem appeared first on Allan Kelly Associates.

October 17, 2017

Reflections on learning and training (and dyslexia)

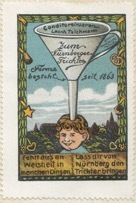

German readers might recognise the image above as a Nuremberg Funnel. For the rest of you: the Nuremberg funnel represents the idea that a teacher can simply open a students head and pour in learning.

First off, a warning: this blog entry might be more for me than for you, but its my blog!

Still, I expect (hope) some of you might be interested in my thoughts and reflections on how training, specifically “Agile training” sessions. More importantly writing this down, putting it into words, helps me think, structure my thoughts and put things in order.

Shall I begin?

I’m not naive enough to think training is perfect or can solve everything. But I have enough experience to know that it can make a difference, especially when teams do training together and decide to change together.

One of the ways I’ve made my living for the last 10 years is by delivering “Agile training.” I don’t consider myself a “trainer” (although plenty of others do), I consider myself more as a “singer songwriter” – it is my material and I deliver it. I’ve actually considered renaming my “Agile training” as “Agile rehearsal” because thats how I see it. I haven’t because I’d have to explain this to everyone and more importantly while people do google for “Agile training” nobody searches for “Agile rehearsal.”

Recently I’ve been prompted to think again about how people learn, specifically how they learn and adopt the thing we call “Agile”. One unexpected experience and one current challenge have added to this.

A few months ago I got to sit in while someone else delivered Agile training. On the one hand I accepted that this person was also experienced, also had great success with what he did, also claimed his courses were very practical and he wasn’t saying anything I really disagreed with.

On the other hand he reminded me of my younger self. The training felt like the kind of training I gave when I was just starting out. Let me give you two examples.

When I started giving Agile training I felt I had to share as much as possible with the attendees. I was conscious that I only had them for a limited time and I had so much to tell them! I was aiming to give them everything they needed to know. I had to brain dump… Nuremberg funnel.

So I talked a lot, sessions were long and although I asked “Any questions?” I didn’t perhaps give people enough time to ask or for me to answer – ‘cos I had more brain dumping to do!

Slowly I learned that the attendees grew tired too. There was a point where I was talking and they had ceased to learn. I also learned that given a choice (“Would you like me to talk about Foobar for 30 minutes or have you had enough?”) people always asked for more.

Second, when I started out I used to include the Agile Manifesto and a whistle-stop-tour of Lean. After all, people should know where this came from and they should understand some of the theory, right? But with time I realised that the philosophy of the manifesto takes up space and isn’t really important. Similarly, Lean is very abstract and people have few reference points. To many (usually younger) people who have never lived “the waterfall” it can seem a crazy straw-man anyway.

Over the years I’ve tried to make my introductions to Agile more experiential. That is, I want to get people doing exercises and reflecting on what happened. I tend to believe that people learn best from their own experience so I try to give them “process miniatures” in the classroom and then talk (reflect) on the experience.

These days my standard starter 2-day Agile training course is three quarters exercises and debriefs. My 1-day “Requirements, User Stories and Backlogs” workshop is almost entirely exercise based. I’m conscious that there is still more stuff – and that different people learn in different ways – so I try to supplement these courses with further reading – part of the reason behind printing “Little Book of User Stories” is to supplement “Agile Reader” in this.

I’m also conscious that by allowing people to learn in different mediums, and to flip between them they can learn more and better.

My own thinking got a big boost when I learned about Constructivist learning theory. Perhaps more importantly I’ve also benefited from exploring my own dyslexia. (Reading The Dyslexic Advantage earlier this year was great.)

Why is dyslexia relevant here? Well two reasons…

Firstly, something I was told a long time ago proves itself time and time again: Dyslexics have problems learning the way non-dyslexics do, but the reverse is not true. What helps dyslexics learn helps everyone else learn better too.

Second: dyslexics look at the world differently and we have to construct their own meaning and find our own ways to learn. To me, Agile requires a different view of the world and it requires us to learn to learn. Three years back I even speculated that Agile is Dyslexic, as time goes by I’m more convinced of that argument.

So why am I thinking so much about all this?

Well, I’ve shied away from online training for a few years now – how can I do exercises? how can I seed reflection?

Now I’ve accepted a request to do some online training. I can’t use my existing material, it is too exercise based. I’m having to think long and hard about this.

One thought is to view “online training” as something different to “rehearsal training.” That is, something delivered through the online medium might be more akin to an audio book, it is something that supplements a rehearsal. But that thinking might be self limiting and ignore opportunities offered online.

The other thing is the commercial medium. As my training has got more experiential and better at helping people move from classroom to action it has actually covered less. The aim is to seed change, although the classroom is supplemented the actual material covered in class is less; learn less change more! – Thats a big part of the reason I usually give free consulting days after training.

In a commercial setting where there is a synopsis and a price tag the incentive is to list more and more content. One is fearful of missing something the buyer considers important. One can imagine a synopsis being placed next to a competitor synopsis and the one with the most content for the least price is chosen.

So, watch this space, I will be venturing into online training. To start off with I’m not sure who is going to be learning the most: the attendees or the presenter! (O perhaps I shouldn’t have said that, maybe I’m too honest.)

If you have any experience with training (as a teacher or student), and especially online training, I’d love to hear about them. Please comment below or email me.

Read more? Subscribe to my newsletter – free updates on blog post, insights, events and offers.

The post Reflections on learning and training (and dyslexia) appeared first on Allan Kelly Associates.

October 13, 2017

Friday throughts on the Agile Manifesto and Agile outside of software

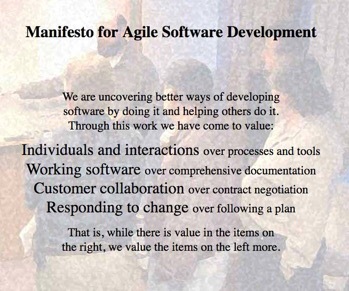

While I agree with the Agile Manifesto I’ve never been a great on for defining “Agile” in terms of it.

As time goes by I find the manifesto increasingly looks like a historic document. It was written in response to the problems in the software industry at the turn of the millennium – problems I recognise because I was there. I worked on the Railtrack privatisation, ISO 9000 certified and so much paper you needed a train to move it. I worked at Reuters as they destroyed their own software capability with a CMM stream roller.

The manifesto is a little like Magna Carta or the US Constitution, you sometimes have to read into it what would fit your circumstances. It was written about software and as we apply agile outside of software you have to think “what would it say?” the same way the US Supreme Court looks at the Constitutions interprets what it would say about the Internet

Perhaps a more interesting question than “What is Agile?” is “Where does Agile apply?” or, even more interesting, “Where does Agile not apply?”

One can argue that since Agile includes a self-adaptation mechanism (inspect and adapt) – or as I have argued, Agile is the embodiment of the Learning Organization – it can apply to anything, anywhere. Similarly it has universal applicability and can fix any flaws it has.

Of cause its rather bombastic to make such an argument and quite possibly anyone making that argument hasn’t thought it through.

So the definition of “Agile” becomes important – and since we don’t have one, and can’t agree on one we’re in a rather tricky position.

Increasingly I see “Agile” (and so some degree Lean too) as a response to new technologies and increasing CPU power. Software people – who had a particular problem themselves – had first access to new technologies (programmable assistants, email, instant messenger, wikis, fast tests and more) and used them to address their own issues.

The problems are important. Although people have been talking about “agile outside of software development” for almost as long as agile software development it has never really taken off in the same way. To my mind thats because most other industries don’t have problems which are pushing them to find a better way.

As technologies advance, and as more and more industries become “Digital” and utilise the same tools software engineers have had for longer then those industries increasingly resembled software development. That means two things: other industries start to encounter the same problems as software development but they also start to apply the same solutions.

Software engineers are the prototype of future knowledge workers.

Which implies, the thing we call Agile is the prototype process for many other industries

“Agile outside of software” becomes a meaningless concept when all industries increasingly resemble software delivery.

Read more? Subscribe to my newsletter – free updates on blog post, insights, events and offers.

The post Friday throughts on the Agile Manifesto and Agile outside of software appeared first on Allan Kelly Associates.

October 6, 2017

Tax the data

If data is the new oil then why don’t we tax it?

My data is worth something to Google, and Facebook, and Twitter, and Amazon… and just about every other Internet behemoth. But alone my data is worth a really tiny tiny amount.

I’d like to charge Google and co. for having my data. The amount they currently pay me – free search, free email, cheap telephone… – doesn’t really add up. In fact, what Google pays me doesn’t pay my mortgage but somehow Larry Page and Sergey Brin are very very rich. Even if I did invoice Google, and even if Google paid we are talking pennies, at most.

But Google don’t just have my data, they have yours, your Mums, our friends, neighbours and just about everyone else. Put it all together and it is worth more than the sum of the parts.

Value of my data to Google < 1p

Value of your data to Google < 1p

Value our combined data to Google > 2p

The whole is worth more than the sum of the parts.

At the same time Google – and Facebook, Amazon, Apple, etc. – don’t like paying taxes. They like the things those taxes pay for (educated employees, law and order, transport networks, legal systems – particularly the bit of the legal system that deals with patents and intellectual property) but they don’t want to pay.

And when they do pay they find ways of minimising the payment and moving money around so it gets taxed as little as possible.

So why don’t we tax the data?

Governments, acting on behalf of their citizens should tax companies on the data they harvest from their users.

All those cookies that DoubleClick put on your machine.

All those profile likes that Facebook has.

Sure there is an issue of disentangling what is “my data” from what is “Google’s data” but I’m sure we could come up with a quota system, or Google could be allowed a tax deduction. Or they could simply delete the data when it gets old.

I’d be more than happy if Amazon deleted every piece of data they have about me. Apple seem to make even more money that Google and make me pay. While I might miss G-Drive I’d live (I pay DropBox anyway).

Or maybe we tax data-usage.

Maybe its the data users, the Cambridge Analyticas, of this world who should be paying the data tax. Pay for access, the ultimate firewall.

The tax would be levied for user within a geographic boundary. So these companies couldn’t claim the data was in low tax Ireland because the data generators (you and me) reside within state boundaries. If Facebook wants to have users in England then they would need to pay the British Government’s data-tax. If data that originates with English users is used by a company, no matter where they are, then Facebook needs to give the Government a cut.

This isn’t as radical as it sounds.

Governments have a long history of taxing resources – consider property taxed. Good taxes encourage consumers to limit their consumption – think cigarette taxes – and it may well be a good thing to limit some data usage. Anyway, thats not a hard and fast rule – the Government taxes my income and they don’t want to limit that.

And consider oil, after all, how often are we told that data is the new black gold?

– Countries with oil impose a tax (or charge) on oil companies which extract the oil.

Oil taxes demonstrate another thing about tax: Governments act on behalf of their citizens, like a class-action.

Consider Norway, every citizen of Norway could lay claim to part of the Norwegian oil reserves, they could individually invoice the oil companies for their share. But that wouldn’t work very well, too many people and again, the whole is worth more than the sum of the parts. So the Norwegian Government steps in, taxes the oil and then uses the revenue for the good of the citizens.

In a few places – like Alaska and the Shetlands – do see oil companies distributing money more directly.

After all, Governments could do with a bit more money and if they don’t tax data then the money is simply going to go to Zuckerberg, Page, Bezos and co. They wouldn’t miss a little bit.

And if this brings down other taxes, or helps fund a universal income, then people will have more time to spend online using these companies and buying things through them.

Read more? Subscribe to my newsletter – free updates on blog post, insights, events and offers.

The post Tax the data appeared first on Allan Kelly Associates.

October 2, 2017

MVP is a marketing exercise not a technology exercise

… Minimally Viable Product

Possibly the most fashionable and misused term the digital industry right now. The term seems to be used by one-side-or-other to criticise the other.

I recently heard another Agile Coach say: “If you just add a few more features you’ll have an MVP” – I wanted to scream “Wrong, wrong, wrong!” But I bit my tongue (who says I’m can’t do diplomacy?)

MVP often seems to be the modern way of saying “The system must do”, MVP has become the M in Moscow rules.

Part of the problem is that the term means different things to different people. Originally coined to describe an experiment (“what is the smallest thing we could build to learn something about the market?”) it is almost always used to describe a small product that could satisfy the customers needs. But when push comes to shove that small usually isn’t very small. When MVP is used to mean “cut everything to the bone” the person saying it still seems to leave a lot of fat on the bone.

I think non-technical people hear the term MVP and think “A product which doesn’t do all that gold plating software engineering fat that slows the team down.” Such people show how little they actually understand about the digital world.

MVPs should not about technology. An MVP is not about building things.

An MVP is a marketing exercise: can we build something customers want?

Can we build something people will pay money for?

Before you use the language MVP you should assume:

The technology can do it

Your team can build it

The question is: is this thing worth building? – and before we waste money building something nobody will use, let alone pay for, what can we build to make sure we are right?

The next time people start sketching an MVP divide it in 10. Assume the value is 10% of the stated value. Assume you have 10% of the resources and 10% of the time to build it. Now rethink what you are asking for. What can you build with a tenth?

Anyway, the cat is out of the bag, as much as I wish I could erase the abbreviation and name from collective memory I can’t. But maybe I can change the debate by differentiating between several types of MVP, that is, several different ways the term MVP is used:

MVP-M: a marketing product, designed to test what customers want, and what they will pay for.

MVP-T: a technical product designed to see if something can be build technologically – historically the terms proof-of-concept and prototype have been used here

MVP-L: a list of MUST HAVE features that a product MUST HAVE

MVP-H: a hippo MVP, a special MVP-L, that is highest paid person’s opinion of the feature list, unfortunately you might find several different people believe they have the right to set the feature list

MVP-X: where X is a number (1,2, 3…), this derivative is used by teams who are releasing enhancements to their product and growing it. (In the pre-digital age we called this a version number.) Exactly what is minimal about it I’m not sure but if it helps then why not?

MVP-M is the original meaning while MVP-L and MVP-H are the most common types.

So next time someone says “MVP” just check, what do they mean?

Read more? Join my mailing list – free updates on blog post, insights, events and offers.

The post MVP is a marketing exercise not a technology exercise appeared first on Allan Kelly Associates.

September 25, 2017

Utilisation and non-core team members

“But we have specialists outside the team, we have to beg… borrow… steal people… we can never get them when we want them, we have to wait, we can’t get them enough.”

It doesn’t matter how much I pontificate about dedicated, stable, consistent teams I hear this again and again. Does nobody listen to me? Does nobody read Xanpan or Continuous Digital?

And I wonder: how much management time is spent arguing over who (which individuals) is doing what this week?

Isn’t that kind of piecemeal resourcing micro-management?

Or is it just making work for “managers” to do?

Is there no better use of management time than arguing about who is doing what? How can the individuals concerned “step up to the plate” and take responsibility if they are pulled this way and that? How can they really “buy in” to work when they don’t know what they doing next week?

Still, there is another answer to the problem: “How do you manage staffing when people need to work on multiple work streams at once?”

Usually this is because some individuals have specialist skills or because a team cannot justify having a full time, 100%, dedicated specialist.

Before I give you the answer lets remind ourselves why the traditional solution can make things worse:

When a resource (people or anything else) is scarce a queues are used to allocate the scarce resources and queues create delays

Queues create delays in getting the work done – and are bad for morale

Queues are an alternative cost: in this case the price comes from the cost-of-delay

Queues disrupt schedules and predictability

In the delay people try to do something useful but the useful thing is lower value, and may cause more work for others, it can even create conflict when the specialist becomes available

The solution, and it is a generic solution that can be applied whenever some scarce resource (people, beds, runways):

Have more of the scarce resource than is necessary.

So that sounds obvious I guess?

What you want is for there be enough of the scarce resource so that the queues do not form. As an opening gambit have 25% resource more than you expect to need, do not plan to use the scarce resource more than 75% of the available time.

Suppose for example you have several teams, each of who needs a UX designer 1-day a week. At first sight one designer could service five teams but if you did that there would still be queues.

Why?

Because of variability.

Some weeks Team-1 would need a day-and-a-half of the designer, sure some week they would need the designer less than a day but any variability would cause a ripple – or “bullwhip effect”. The disruption caused by variation would ripple out over time.

You need to balance several factors here:

Utilisation

Variability

Wait time

Predictability

Even if demand and capacity are perfectly matched then variability will increase wait time which will in turn reduce predictability. If variability and utilisation are high then there will be queues and predicability will be low.

If you want 100% utilisation then you have to accept queues (delay) and a loss of predicability: ever landed at Heathrow airport? The airport runs at over 96% utilisation, there isn’t capacity to absorb variability so queues form in the air.

If you want to minimise wait time with highly variable work you need low utilisation: why do fire departments have all those fire engines and fire fighters sitting around doing nothing most days?

Running a business, especially a service business, at 100% utilisation is crazy – unless your customers are happy with delays and no predicability.

One of the reasons budget airlines always use the same type of plane and one class of seating is to limit variation. Only as they have gained experience have they added extras.

Anyone who tries to run software development at 100% is going to suffer late delivery and will fail to meet end dates.

How do I know this?

Because I know a little about queuing theory. Queuing theory is a theory in the same way that Einstein’s Theory of Relativity is theory, i.e. it is not a theory, its proven. In both cases mathematics. If you want to know more I recommend Factory Physics.

So, what utilisation can you have?

Well, that is a complicated question. There are a number of parameters to consider and the maths is very complicated. So complicated in fact that mathematicians usually turn to simulation. You don’t need to run a simulation because you can observe the real world, you can experiment for yourself. (Kanban methods allow you to see the queues forming.)

That said: 76% (max).

Or rather: in the simplest queuing theory models queues start to form (and predictability suffers) once utilisation is above 76%.

Given that your environment is probably a lot more complicated then the simplest models you probably need to keep utilisation well below 76% if you want short lead times and predictability.

As a very broad rule of thumb: if you are sharing someone don’t commit more then three-quarters of their time.

And given that, a dedicated specialist doesn’t look so expensive after all. Back to where I came in.

<

blockquote>Read more? Join my mailing list – free updates on blog post, insights, events and offers.

The post Utilisation and non-core team members appeared first on Allan Kelly Associates.

September 11, 2017

Continuous Digital & Project Myopia

This seems a little back to the future… those of you who have been following the evolution of Continuous Digital will know the book grew out of the #NoProjects meme and my extended essay.

I think originally the book title was #NoProjects then was Correcting Project Myopia, then perhaps something else and finally settled down to Continuous Digital. The changing title reflected my own thinking, thinking that continued to evolve.

As that thinking has evolved the original #NoProjects material has felt more and more out of place in Continuous Digital. So I’ve split it out – Project Myopia is back as a stand alone eBook and you can buy it today.

More revisions of Continuous Digital will appear as I refactor the book. Once this settles down I’ll edit through Project Myopia. A little material may move between the two books but hopefully not much.

Now the critics of #NoProjects will love this because they complain that #NoProjects tells you what not to do, not what to do. In a way I agree with them but at the same time the first step to solving a problem is often to admit you have a problem. Project Myopia is a discussion of the problem, it is a critique. Continuous Digital is the solution and more than that.

Splitting the book in two actually helps demonstrate my whole thesis.

For a start it is difficult to know when a work in progress, iterating, self-published, early release book is done. My first books – Business Patterns and Changing Software Development – were with a traditional publisher. They were projects with a start and a finish. Continuous Digital isn’t like that, it grows, it evolves. That is possible because Continuous Digital is itself digital, Business Patterns and Changing Software Development had to stop because they were printed.

Second Continuous Digital is already a big book – much bigger than most LeanPub books – and since I advocate “lots of small” over “few big” it makes sense to have two smaller books rather than one large.

Third, and most significantly, this evolution is a perfect example of one of my key arguments: some types of “problem” are only understood in terms of the solution. Defining the solution is necessary to define the problem.

The solution and problem co-evolve.

In the beginning the thesis was very much based around the problems of the project model, and I still believe the project model has serious problems. In describing a solution – Continuous Digital – a different problem became clear: in a digital age businesses need to evolve with the technology.

Projects have end dates, hopefully your business, your job, doesn’t.

If you like you can buy both books together at a reduced price right now.

Read more? Join my mailing list – free updates on blog post, insights, events and offers.

The post Continuous Digital & Project Myopia appeared first on Allan Kelly Associates.

Allan Kelly's Blog

- Allan Kelly's profile

- 16 followers