Allan Kelly's Blog, page 30

January 20, 2018

Nature abhors an information void

No. 6: What do you want?

Voice: Information

No. 6:You won’t get it

Voice: By hook or by crook we will

Information… we all want information… Facebook updates, Tweets, 24-hour rolling news, the Donald Trump Big Brother House… the opening scenes and words of The Prisoner continue to echo, Patrick McGoohan and the other writers got it right, they were just 50 years early.

Human beings have insatiable thirst for information – even when we know rationally that information is useless is pointless we still want it. We persuade ourselves that something might be happening that we need to know about.

Just today I was driving when my mobile phone started to ring. It was highly unlikely to be anything but still my mind started to think of important things it could be. I had to stop the car and try to answer it. Of course, it was spam, a junk call, caller-ID told me that so I didn’t answer.

Every one of us has information weaknesses. In part it is dopamine addiction. We may look down on those who watch “vanity metrics” but we all information fetishes whether they be, metrics, scores, “facts” or celebrity gossip.

Whether e-mail, Twitter, Facebook, WhatsApp, SMS, Slack, some other medium or social media we all need information and a dopamine fi. Has only replied to my tweet? Has anyone retweeted my last tweet? Has anyone followed me today?

Sometimes it is impossible to believe that nobody has retweeted my fantastic tweet, or that a potential client hasn’t immediately replied to an e-mail, or that… I’ve even on occasions found myself picking up my phone and going to the mail app when I’ve only just walked away from answering e-mail on my PC – as if the e-mail on my phone is better than the e-mail on my PC!

The only thing worse than having a mailbox full of unanswered e-mails is an empty mailbox – mailbox zero – which stays empty.

Sometimes one demands information when there just isn’t any. I think that is what number 6 really meant when number 2 repeatedly asked him for information: there wasn’t anything more than he had said. He had given his information, if others demanded more then it was simply because they couldn’t accept what they had been told.

I’m sure all parents have experienced children in the back of the car who ask: “Are we there yet?”. To which you reply “No – it will be at least an hour”. And then, five minutes later you hear “Are we there yet?”

And who hasn’t felt the same way about project managers? Or technical leads? Or product managers? product owners? business analysts?

Children don’t stop asking because… well, maybe because they don’t understand the answer, they have a poor concept of time. Or maybe because they really want the answer to be “Yes we are there.” As small people children also want information.

Isn’t that the same when other people ask you the “Have you finished foo yet?” and even “When will it be ready?” While one hopes they have a better concept of time they don’t necessarily take in the answer, and they hope and hope and hope that the answer will soon be the answer they want it to be. People are very bad at handling information voids.

Manager types might dress the question up in terms of “The business needs to know” how often does that disguises the real truth: somebody didn’t like the last answer and is hoping that if the question is posed again the answer might be the one they want.

The project manager who checks in every few hours is no different than the developer who leaves their e-mail open on a second screen, or the tester keeps Twitter in the background. Each of them wants to know information!

Our difficult in dealing with information voids means we constantly search for information. And if we can’t find it we create pseudo-information: time based project plans which purport to show when something will be done or system architecture documents which claim to show how everything will work. Are the project managers and architects who create these documents are just seeking information? Dopamine?

Long time readers may remember my review of time-estimation research. Some of the research I read showed that people in positions of authority, or who claimed expert knowledge, underestimates how long work will take more than the people who do the work. Researchers were not clear as to whether this effect was because those in authority and experts let their desire for the end state influence their time estimation or whether it was because these people lacked an understanding of the work in detail and so ignored complications.

And it is not just time based information. Requirements documents are often an attempt to discern how a system may be used in future. System architecture designs are an attempt to second guess how the future may unfold. Unfortunately, as Peter Drucker said “We have no facts about the future”.

Faced with an information void we fill it with conjecture.

Sadly I also see occasions where the search for answers disables people. Sometimes people search for information and answers which are within their own power to give. Consider the product owner inundated with work requests for their product. They search for someone to tell them what they should do and what they should not do. Faced with an information void they look for answer from others. But sometimes – often? always? – the answer is within: as product owner they have the authority to decide what comes first and what is left undone.

I have become convinced over the years that often people ask for information that simply doesn’t exist. When the information isn’t presented they fill in the blanks themselves, they assume the information does exist and isn’t being shared. In some cases they create conspiracy theories or they accuse others of being secretive. But because of doubt they they don’t act on the information.

It is easy to think of examples in the public eye but I think it also happens inside organizations. Often times managers really don’t know what the future will hold but if they don’t tell people then they are seen as hiding something. If they deny information exists they may be seen as stupid or misleading.

The same happens the other way around, the self same managers – who really don’t know as much as people think they do – ask programmers, testers, analysts, etc. for information which doesn’t exist and which maybe unknowable. Telling your manager “you don’t know” might not be something you feel safe doing, and if you do then they may go and ask someone else.

In almost every organization I visit people tell me “We are not very good at communicating around here.” Again and again people tell me they are not told information they “should” be told. I’ve never visited an organization where people tell me “Communication is great around here” and while I’ve visited places where people say “We have lots of pointless meetings” nobody tells me “We are told too much.”

My working assumption in these cases is simply: The information doesn’t exist.

This is Occam’s razor logic, it is conspiracy free, it doesn’t assume the worst of people. I don’t assume people are keeping information secret – either deliberately or through naive understandings of what other people want.

So, the real answer for No. 6 should be “I’ve told you the truth, maybe you can’t accept it.”

Read more? Subscribe to my newsletter – free updates on blog post, insights, events and offers.

The post Nature abhors an information void appeared first on Allan Kelly Associates.

January 11, 2018

I am guilty of Agile training

Over Christmas I was thinking, reflecting, drinking…

Once upon a time I was asked by a manager to teach his team Agile so the team could become Agile. It went downhill from there…

I turned up at the clients offices to find a room of about 10 people. The manager wasn’t there – shame, he should be in the room to have the conversations with the team. In fact half the developers were missing. This company didn’t allow contractors to attend training sessions.

For agile introduction courses I always try and have a whole team, complete with decision makers, in the room. If you are addressing a specialist topic (say user stories or Cucumber) then its OK to have only the people the topic effects in the room. But I am talking about teams and processes, well I want everyone there!

We did a round of introductions and I learned that the manager, and other managers from the company, had been on a Scrum Master course and instructed the team to be Agile. Actually, the company had decided to be Agile and sent all the managers on Scrum Master courses.

So the omens were bad and then one of the developers said something to the effect:

“I don’t think Agile can help us. We have lots of work to do, we don’t have enough time, we are already struggling, there is masses of technical debt and we can’t cut quality any further. We need more time to do our work not less.”

What scum am I? – I pretend to be all nice but underneath I allow myself to be used as a tool to inflict agile pain on others. No wonder devs hate Agile.

My name is Allan and I provide Agile training and consulting services.

I am guilty of training teams in how to do Agile software development.

I am guilty of offering advice to individuals and teams in a directive format.

I have been employed by managers who want to make their teams agile against the will of the team members.

I have absented myself from teams for weeks, even months and failed to provide deep day-in-day-out coaching.

In my defence I plead mitigating circumstances.

One size does not fit all. The Agile Industrial Complex* has come up with one approach (training, certification and enforcement) and the Agile Hippies another (no-pressure, non-directive, content free, coaching).

I don’t fit into either group. Doing things differently can be lonely … still, I’ve had my successes.

I happen to believe that training team members in “Agile” can be effective. I believe training can help by:

Providing time for individuals to learnSharing the wisdom of one with othersProviding the opportunity for teams to learn together and create a shared understandingProviding rehearsal space for teams to practice what the are doing, or hope to doProviding a starting-point – a kick-off or a Kaikaku event – for a reset or changeand some other reasons which probably don’t come to mind right nowYes, when I deliver training I’m teaching people to do something, but that is the least important thing. When I stand up at the start of a training session I image myself as a market stall holder. On my market stall are a set of tools and techniques which those in the room might like to buy: stand-up meetings, planning meeting, stories, velocity, and so on. My job is to both explain these tools and inspire my audience to try. I have a few hours to do that.

As much as I hate to say it, part of my job at this point is Sales. I have to sell Agile. In part I do that by painting a picture of how great the world might be with Agile. I like to think I also give the audience some tools for moving towards that world.

At the end of the time individuals get to decide which, if any, of the tools I’ve set out they want to use. Sometimes these are individual decisions, and sometimes individuals may not pick up any tools for months or years.

On other occasions – when I have time – I let the audience decide what they want to do. Mentally I see myself handing the floor over to the audience to decide what they want to do. In reality this is a team based exercise where the teams decide which tools they want to adopt.

If a team wants to say “No thank you” then so be it.

In my experience teams adopting Agile benefit greatly from having ongoing advice on how they are working. Managers benefit from understanding the team, understanding how their own role changes, and understanding how the organization needs to change over time.

Plus: you cannot cram everything a team need to know into a few hours training and it would be wrong todo so. You don’t want to overload people at the start. There are many things that are better talked about when people have had some experience.

Actually, I tend to believe that there are some parts of Agile which people can only learn first hand. They are – almost – incomprehensible, or unbelievable until one has experience. That is one of the reasons I think managers have trouble gasping agile in full: they are too far removed from the work to experience it first hand.

You see, I believe everyone engages in their own sense making, everyone learns to make sense and meaning in the world themselves. In so much as I have a named educational style it is constructivist. But my philosophy isn’t completely joined up and has some holes, I’m still learning myself.

When I do training I want to give people experiences help them learn. And that continues into the work place after the training.

So I also offer coaching, consulting, advice, call it what you will.

But I don’t like being with the team too much. I prefer to drop in. I believe that people, teams, need space to create their own understanding. If I was there they wouldn’t get that space, they wouldn’t have those experiences, and possibly they wouldn’t take responsibility for their own changes.

One of my fears about having a “Scrum Master” type figure attached to a team is that that person becomes the embodiment of the change. Do people really take responsibility and ownership if there is someone else there to do it?

I prefer to drop in occasionally. Talk to individuals, teams, talk about how things are going. Talk about their experience. Further their sense making process. Do some additional exercises if it helps. Run a retrospective.

And then I disappear. Leave things with them. Let them own it.

Whether technical skills are concerned – principally TDD – it is a little different. Because that is a skill that needs to be learned by practice. I don’t tend to do that so I usually involve one of my associates and they are sometimes embedded with a team for a longer period.

Similarly, I do sometimes become embedded in an organization. I can be there for several days a week for many weeks on end. That usually occurs when the organization is larger, or when the problems are bigger. Even then I want to leave as much control with the teams as I can.

On the one hand I’m a very bad person: I accept unwilling participants on my training courses and then don’t provide the day-to-day coaching that many advocate.

On the other hand: what I do works, I’ve seen it work. Sometimes one can benefit from being challenged, sometimes one needs to open ones mind to new ideas.

If I’m guilty of anything I’m guilty of having a recipe which works differently.

And that team I spoke of to start with?

One day two some people did not return: that was a win. They had worked out that it was not for them and they had taken control. That to me is a success.

Most people did return and at the end, the one who had told me Agile could do nothing for them saw that Agile offered hope. That hope was principally an approach to quality which was diametrically opposite to what he initially thought it was going to be and was probably, although I can’t be sure, the opposite of what his manager thought Agile meant.

It is entirely possible that had his manager been in the room to hear my quality message I’d have been thrown out there and then. And its just possible I might have given him food for thought.

But I will never know. I never heard from them again. Which was a shame, I’d love to know how the story ended. But that is something else: I don’t want to force anyone to work with me, I don’t lock people in. That causes me commercial headaches and sometimes I see people who stop taking the medicine before they are fully recovered but thats what happens when you allow people to exercise free will.

O, one more thing, ad advert, I’m available for hire, if you like the sound of any of that then check out my Agile Training or just get in touch.

*Tongue in cheek, before you flame me, I’ve exaggerated and pandered to stereotypes to effect and humour.

Read more? Subscribe to my newsletter – free updates on blog post, insights, events and offers.

The post I am guilty of Agile training appeared first on Allan Kelly Associates.

December 21, 2017

Conclusion: Who works on what – Comparative advantage part 3 of 3

In my last two posts – Who should work on what? part1 and part 2 – I’ve tried to apply the comparative advantage model from economics to the question of which software developer should work on what. The model has come up with two different answers:

If productivity (measured by quantity of features is the goal) then it probably makes sense for everyone to work on the product that they are comparatively most productive on (comparatively being the key word here.)If value produced in the goal then it may well make sense for everyone to work on the most valuable features (or product) regardless of personal strengths.Along the way I’ve highlighted a number of difficulties in applying this model:

At this point it is tempting to throw ones hands up in the air and say: “We’ve learned nothing!”

But I don’t think so. I think there are lessons in here.

Right at the start of this I knew this was a difficult question to answer, trying to answer it has shown just how hard it is to get a definitive answer. There are still more assumptions which could be relaxed in this model and still more variables that could be added.

The model has also shown how important it is to have a sense of value. Not only between products but between features. That in turn demonstrates the importance of both valuing work in the backlog and regularly reviewing those valuations.

However, the first big lesson I think that needs learning here is: you have to know what your intention is.

You need to know what you are trying to optimise.

You need a strategy.

For example:

In many this is going to be a self-fulfilling prophecy, the result will be what you put in. That is, if people only work on one product then moving people between products will get harder and less productive. If people follow the value then value delivered will increase as people become more productive in the products with the higher value.

Knowing what your intention is should be the first step to formulating a strategy. And having a strategy is important because answering that question – “who should work on what?” – is hard.

To answer that question rationally one needs to create a model, a model far more complex than my model, then calculate every variable in the model – plus keep the variables up to date as they change. Then to apply that model to every work question which arises.

Phew.

Alternatively one can formulate a rule of thumb, a heuristic, a rough guideline, a “good enough” decision process. This might sound a bit amateurish but as Gerd Gigerenzer says in Risk Savvy:

“To make good decisions in an uncertain world, one has to ignore part of the information, which is exactly what rules of thumb do. Doing so can save time and effort and lead to better decisions.”

To build up such rules of thumb requires experience and reflection, something which might be described as intuition.

So to answer my original question in terms an economist would recognise: It depends.

Read more? Subscribe to my newsletter – free updates on blog post, insights, events and offers.

The post Conclusion: Who works on what – Comparative advantage part 3 of 3 appeared first on Allan Kelly Associates.

December 20, 2017

Adding value – Who works on what? – part 2 of comparative advantage

In my previous post I tried to use the economic theory of comparative advantage to answer the question:

Who should work on what? or Shouldn’t every developer work on the software where they are most productive?

The economic model gave an answer but more importantly it provided a framework for answering the question. As I examined the assumptions behind the model it became clear there are many other considerations which deserve attention.

Perhaps the most important one is: value.

The basic economic model looks, perhaps naively, at quantity of goods produced. Really, one should consider the value of the goods produced. Not only did the model assume that every feature is the same size but it also assumed that all features have the same value.

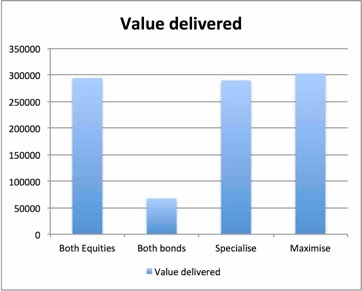

Flipping back to the basic model, lets assume that each Bonds feature generates $10,000 in revenue while each Equities feature generates $20,000. Now the options are:

Jenny and Joe both work on Equities, they produce seven features and generate $140,000 in revenue.Jenny and Joe both work on Bonds, they produce seven features and generate $70,000 in revenue.Joe works on Equities and Jenny on Bonds, the six features they produce generate $80,000 in revenue.Joe works on Bonds and Jenny on Equities, the eight features they produce generates $130,000 in revenue.Clearly option #1 is the one to choose because it generates the greatest revenue even though Joe would be more productive if he were to work on Bonds. Adding value to the basic model changes the answer.

Now, again there is an assumption here: all features produce the same value. That is unlikely to be true.

Indeed, over time if no work is done on Bonds it would be reasonable to assume the value of the features would increase. Not that all features would increase in value but failure to do any would mean some of those in the backlog would become more valuable. In addition new requests might arise which may be more valuable than existing requests.

Further, while the value of Bonds features would be increasing the value of Equities might be falling. This follows another economic theory, the law of diminishing marginal utility. This law states that as one consumes more of a given product the added utility (i.e. value) derived from one more unit will be less and less.

So now we have exposed another assumption in the model: the model is static. The model does not consider the effects over time of how things change – I’ll come back to this in another context later too.

Over time the backlogs for both products will stratify, each will contain some items which are higher in value than average and some which are lower in value.

Lets suppose each product has its own backlog:

Equities backlog contains seven features with the values: $60,000, $54,000, $48,000, $42,000, $36,000, $30,000 and $24,000.Bonds backlog contains another seven features with the values: $32,500, $10,000, $7,000, $6,000, $5,000, $4,000 and $,3000.Now there are (at least) four options open:

The highest value option if #4, which delivers $13,000 more than if they specialise. That might seem counter intuitive: the option that delivers the most money delivers the least features. And again it shows deciding work in the absence of value can be misleading.

The second best option is for both to do Equities only, this delivers $8,500 more than specialisation. Adding value to the basic model isn’t a big change but it has changed the answer. When output was measured in features then specialisation looked to be the best option.

Returning to the question of the static model, there is one more assumption to relax: Learning. Economist J.K.Galbraith pointed out that the comparative advantage neglects to factor in learning, and I’ve done the same thing so far.

Assuming Joe specialises in Bonds and spends most of his time working there he will learn and in time he will become more productive. Suppose after a year he can produce 5 bonds features in the time he takes to produce 2 equities features – a 66% improvement.

Now how to the numbers stack up? What is the revenue maximising choice now?

And perhaps more importantly, how long would it take before Joe’s increased output paid for all the time he spent learning?

But, another what-if, what if Joe had specialised in Equities instead? He would now be more productive on a product with higher value features.

Again the question “Who should work on what?” needs to consider intent. Which product do you want Joe to learn? Which product is expected to have the highest value? Are you maximising value or quantity?

As usual, you can argue with my model and question my assumptions but I think that only demonstrates my point: these things need thinking about.

If you want you can continue relaxing the assumptions and do more what-if calculations – for example I’ve assumed Jenny and Joe cost the same. Nor have I factored in risk or cost-of-delay. This model can get a lot more complicated. I’ve also assumed that partially done features have no value at all, each week starts afresh and no work carries over.

Read more? Subscribe to my newsletter – free updates on blog post, insights, events and offers.

The post Adding value – Who works on what? – part 2 of comparative advantage appeared first on Allan Kelly Associates.

December 19, 2017

Who should work on what? – Comparative advantage part 1

Returning to my theme of numerical and economic analysis of software development, I’d like to address that old chestnut:

Shouldn’t every developer work on the software where they are most productive?

We can model this question using a bit of economic theory called Comparative advantage – which is also the economics that justifies free trade. However, while this model will give us an answer it also raises a number of questions which are outside the model. In this case the model gives us a structure for examining the issues rather than providing an answer.

By the way, this discussion is going to span two blog posts, or perhaps three.

Lets set up the model with a simple case. As before there are some assumptions needed, its when we examine these assumptions that things get really interesting.

Imagine a small trading desk. The desk invests in corporate bonds and equities. Jenny has been working for the desk for some years and has written two applications for trading imaginatively called Equities and Bonds. She wrote Equities after Bonds and prefers Equities and is more productive on Equities.

Measured in features Jenny can produce 5 new Equities features or 4 new Bonds features in one week. (We’ll assume that all features are the same size for now.)

The company hires a new developer, Joe. He is new to the code bases he can only produce 2 Equities features or 3 Bonds features a week. Thus Jenny is the most productive developer on both apps.

Features per weekEquities

BondsJenny5

4

Joe2

3

Now comparative advantage theory tells us not to look at the total output of either party but at the relative output. In other words:

Looked at this way, relatively, Jenny is a better (more productive) Equities developers and Joe is the most productive Bonds developer.

Think about that.

During one week Jenny can produce more Bonds features than Joe but when measured in terms of the alternative Joe is the more productive Bonds developer. This is the important point. You might say “look at everyones individual strengthens.” Relatively Joe is better at Bonds.

Together Jenny and Joe could produce 7 features for either product. If Jenny works where she is stronger, Equities, and Joe works where he is strongest, Bonds, then together they will produce 8 features. If they both worked on their weaker product then they will only produce 6 features combined but four of those six would be Bonds features.

So, it seems the case solved: Everyone should specialise and work on the product where the individual is relatively strongest. Although this is not necessarily the same as “who is the best developer” for a product.

But… things are more complex. Now we have the model we can start changing the assumptions and see what happens.

First off, we could relaxed the assumption about all features being a different size. However this doesn’t make any real difference. It doesn’t matter how big a feature is, Jenny is always 20% more productive on Equities than Bonds and similarly Joe is 50% more productive on Bonds than Equities. Using different size features complicates the model without creating new insights.

Varying the size of features doesn’t change the integrity of the model but it does make a difference if we start to look at throughput and consider time.

So lets relax the time assumption. What happens if Joe is in the middle of a Bonds feature and another feature gets flagged up as urgent. Should Joe drop what he is doing and pick up the urgent Bond feature?

The model doesn’t answer this question. The model is only measuring output. If we are attempting to maximise output then changing work part way through the week only makes sense if the both pieces of work – the part done original and the urgent interrupt – can still be completed by the end of the week.

So one needs to ask: is the feature urgent enough to justify Joe halting his current work and doing the new feature? Then perhaps returning to his current work?

Possibly but in making one feature arrive faster another would be delayed. Statistically there is little difference because the differences cancel each other out. Which itself demonstrates how managing by numbers can be misleading.

And what is Joe couldn’t finish both pieces by the end of the week? Would it make sense to reduce overall efficiency to expedite some work?

What if Jenny becomes available, should she work on Bonds? Even though she is relatively less productive at Bonds and would thus delay even more Equities features?

These questions can be answered in many different ways but answering them depends on what you are trying to maximise. And lets also note that in real life the data is unlikely to be so clear cut

On average Joe takes two and a half days to complete an Equities feature while Jenny completes one Equities feature a day. On average Jenny can complete her current feature and a second one before Joe could. But it doesn’t take much to invalidate that answer, in particular if feature sizes vary things change.

What if Jenny is working on an over-sized feature? – well call it urgent #1. Suppose urgent #1 is twice as big as urgent #2 and she has just started #1. Jenny will take three days to finish both features. If goes starts urgent #2 he will have it finished in 2.5 days, during that time Jenny will have urgent #1 finished. Looked at this way it makes sense for Joe to work on the highest priority even if it takes him longer.

And what happens if Equities has three, or more, urgent features? Even with Joe working more slowly than Jenny all the urgent features will be delivered sooner if Joe works on Equities too. Again, total productivity would be impacted but what is more important: total productivity or rapid delivery?

If efficiency is your objective then all is well, simply understand the relative efficiency of individuals and do the maths. (Except of course, understanding the efficiency of any individual isn’t that straight forward.) Adding time dependent features complicates things, the comparative advantage model helps show the cost of urgency although it cannot answer the question.

It is entirely possible, even likely, that efficiency is not the only concern, it may not even be the primary concern. Rather the timeliness of feature delivery may be more important.

Specifically, I have assumed that all features are about the same effort but I’ve assumed they are also the same value. Efficiency has been measured as quantity of units produced is a poor measurement compared with efficiency in value delivered. I’ll turn my attention to value in the next blog.

But before I leave this post, one more assumption to surface.

In this model Joe and Jenny are completely independent. There work does not impact the other and they share no resources. What if they did?

What if both Joe and Jenny handed their completed work to the same Tester? Or they both needed use of s single test environment? Or their work needed to be bundled into a common release?

In such cases the shared resource – the tester, the environment, the release schedule – would become the constraint on productivity. This is getting towards Theory of Constraints space.

For Joe and Jenny to work at their most productive not only would that bottleneck need enough capacity to service them both it would actually need more capacity to cope with the variation and peak load (when Jenny and Joe delivered at the same time.)

Providing that extra capacity at the bottleneck would allow Joe and Jenny to work at their maximum throughput but would introduce waste because the extra capacity would sometimes be idle. To tackle that question one needs a far more complex theory: Queuing Theory – which I’ve discussed in previous posts, Utilisation and non-core team members and Kanban: efficient or predictable, you decide.

Read more? Subscribe to my newsletter – free updates on blog post, insights, events and offers.

The post Who should work on what? – Comparative advantage part 1 appeared first on Allan Kelly Associates.

December 15, 2017

I’m delighted – I’m in the 20 TOP Agile Blogs

I’m delighted, this blog has been listed in the “20 TOP Agile Blogs for Scrum Masters (2017 edition)”.

I recognise most of the other bloggers in this list and frankly it is an honour to be classed with them.

(The news also gives me something to publish in this blog be because I’m real and truly stalled on next economics piece! Requires some analysis.)

The post I’m delighted – I’m in the 20 TOP Agile Blogs appeared first on Allan Kelly Associates.

December 6, 2017

When does a Start-Up need Agile?

I started writing another piece on more economic and agile/software development but it got to long, so right now, an aside…

Back in 1968 Peter Drucker wrote:

“Large organizations cannot be versatile. A large organization is effective through its mass rather than through its agility.”

Last week I presented “Agile for Start-ups” here in London for the third time. Each time I’ve given this talk it has been largely rewritten – this time I think I’ve got it nailed. Part of the problem is I tend towards the view that “Start-Ups don’t need Agile”, or rather they do, but agile comes naturally and if it doesn’t then the start-up is finished. Its later when the company grows a bit that it needs Agile. And notice here, I’m differentiating between agile – the state of agility – and Agile as a recognised method.

New, energetic, start-ups are naturally agile, they don’t need an Agile method. As they grow there may well come a time when an Agile method, specific Agile tools, are useful in helping the start-up keep its agility. Am I splitting hairs?

For a small start-up agile should be a natural advantage. On day one, when there are two people in a room making the startup it isn’t a question of what process they are going to follow. At the very beginning a start-up lives or dies by two things: passion and a great idea. In the beginning it should be pure energy.

In many ways the ideas behind Agile are an effort to help companies maintain this natural agility as they grow. Big, established, companies who have lost any natural agility seem to resemble middle aged men trying to recapture a lost youth.

So when does a start-up need to get Agile? – a more formal way of keeping fit as it where.

Not all day-1 start-ups are pure passion, ideas and energy. Some need to find their thing. They need an approach to finding their reason for being. Agile can provide that structure.

And start-ups which are taking a Lean Start-Up approach also need a method. They may have passion and energy in the room but the lean startup market test driven approach demands discipline and iteration. Lean Start-Up demands you kill your children if nobody wants them.

When I look at Lean Start-Up I see an engineer’s solution to the problem of “What product should our company build to be successful?” The engineered solution is to try something, see what happens, learn from the result, maybe build on the try or perhaps change (pivot) and repeat.

In both these cases a start-up needs to be able to Iterate: Try something, see what happens, learn from it and go round the loop again.

You can generalise these two cases to one: Product Discovery through repeated experimentation.

That requires a discipline and it requires a method – even if the method is informal and subject to frequent change. It can be supplemented with traditional research and innovation approaches.

The next time a start-up can benefit from Agile (as in a method) is as it grows: as it becomes a “scale-up” rather than a start-up. This might be when you grow from two to three, or from 10 to 13, or even 100 to 130 but at some point the sheer energy driven nature of a start-up needs to give way to more structure.

This probably coincides with success – the company has grown and survived long enough to grow. Someone, be they customers or investors, is paying the company money. It is no longer enough to rely on chance.

The problem now is that introducing a more defined method risks damaging the culture and way the start-up is working – which is successful right now. So now the risk of change is very real, there is something to loose!

Just as the company can think about the future it needs to risk that future. But no change is also risky, with growth the processes and practices which brought initial success may not be sustainable in a larger setting.

This is the point where I’ve seen many companies go wrong. They go wrong because they decide to become a “proper company” and do things properly. Which probably means adding some project managers and trying to be like so many other companies. They give up their natural agility.

Innovation in process goes out the window and attempts to turn innovative work into planned projects are doomed. Show me the project plan with a date for “Innovation happens here” or “Joe gets great idea in morning shower” or “Sam bumps into really big contact.”

It is at this point that I think Agile methods really can help. But those approaches need to be introduced carefully working with the grain of the organization. Some eggs are bound to be broken but this shouldn’t be a scorched earth policy.

Start-ups and scale-ups need to approach their products and Agile introduction as they do their business growth: organically. Grow it carefully, don’t force feed it, don’t impose it – inspire the staff to change and let them take the initiative.

It is much easier to do this while the team is small. Changing the way one team of five works is far easier than changing the way four teams of eight work. Its also cheaper because once one team is working well it can grown and split – amoeba like – and later teams will be born with good habits.

Unfortunately companies, especially smaller ones, put a lot of faith in hiring more people to increase their output and thereby postpone the day when the team adopt a more productive and predictable style of working.

This might be because they believe new hires will have the same work ethic and productivity as the early hires: they probably won’t if only because they have more to learn (people, code, processes, domain) when they start.

Or it might be because the firm doesn’t want to loose productivity while they change: in my experience, when the change is done right short term productivity doesn’t fall much and quickly starts growing.

It might just be money saving: why pay for training and advice today? – yet such advice isn’t expensive in the scheme of things, certainly delaying a new hire by a couple of months should cover it.

Or it might just be the old “We haven’t got time to change” problem. Which always reminds me of a joke Nancy Van Schooenderwoert once told me:

“A police officer sees a boy with a bicycle walking along the road at 10am.

Police: Excuse me young sir, shouldn’t you be in school?

Boy: Yes officer, I’m rushing there right now.

Police: Wouldn’t it be faster to ride your bike down the hill?

Boy: Yes officer, but I don’t have the time to get on the bike.”

Read more? Subscribe to my newsletter – free updates on blog post, insights, events and offers.

The post When does a Start-Up need Agile? appeared first on Allan Kelly Associates.

November 29, 2017

Allan’s new Law of Social Networks

“The more social networks one joins the less one interacts with any one social network”

Just saying.

Please don’t create another social network. If you need a social network please piggy back on an existing one: Facebook, LinkedIn, Instagram, Pinterest, ….

If you think you need a social network – perhaps to challenge one of the existing ones? – remember Google Plus.

And make sure you know why you will succeed where Google failed.

Almost certainly you have less resources than Google.

Almost certainly you have a smaller existing user base then Google.

Almost certainly Google will see you as a competitor (as will Facebook, and LinkedIn/Microsoft, Instagram…)

So unless you are in fact the Google evil-empire don’t even think about it. And if you are Google remember you already failed, twice – remember Orkut?

Only a company as rich as Google can maintain the pretence that Google Plus was not an abject failure.

The post Allan’s new Law of Social Networks appeared first on Allan Kelly Associates.

November 22, 2017

1% improvement

Keeping with the numerical and financial theme of the last couple of blogs I want to turn my attention to improvement and how really small improvements add up and can justify big spending. This also turns out to be the case for continual improvement and continual delivery…

How would you like it if I promised to improve your team by 1%? – I’m sure I can!

How much difference would it make if your team were 1% more productive?

Not a lot I guess.

More importantly, you’re going to have trouble making that sale to the powers that be.

You: Boss, I’d like to hire Allan Kelly as consultant for a few days to advise the team on how to improve.

Boss: How much do you expect them to improve?

You: He guarantees a 1% improvement or your money back

Boss: One Percent? 1%? Just 1%? Whats he charging $10?

No, thats not going to work is it.

People who hold the money like to see big numbers. The problem is, if the numbers are too big they become unbelievable. Those in authority want to see a significant improvement but the bigger the numbers are then the more evidence they want to see that the improvement is achievable. And when the number are big they need to be proven and that can slow everything down.

On the other hand, there are stories of teams winning (and I do mean winning) by focusing on 1% improvements. At Pipeline conference last year John Clapham talked about how the UK cycling team worked on 1% improvements. And I’ve heard several stories about Formula-1 racing teams who work hard to get 1% improvement. After all, Formula-1 racing cars are already pretty fast so getting 1% is pretty hard.

So what is it about 1%?

Surely 10% is better?

The thing is, 10% is going to be better but getting 10% is hard. Getting 1% can be hard enough, getting 10% can be 100 times harder. Even finding the things that deliver 10% improvement can be hard. On the other hand, for the typical software team, there are usually a bunch of 1% improvements to be had easily.

The trick with 1% is to get 1% again and again and again…

The trick with 1% improvement is… iteration: to get 1% improvement on a regular basis and then allow the effects of compound interest to work their magic.

The size of the improvement is less important than the frequency of the improvement. Taking “easy wins” and “low hanging fruit” makes sense because it gets you improving. Sure 10% may make a much bigger difference but you have to find the 10% improvement, you have to persuade people to go for it, you probably have to mobilize resources to get it and so on.

1% should be far easier.

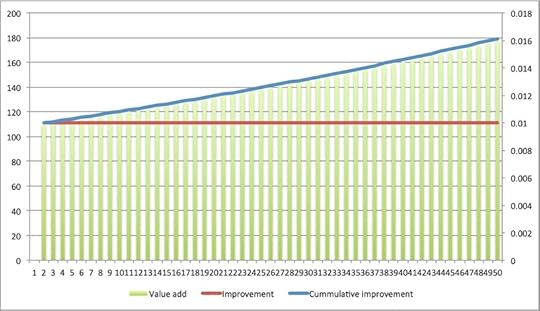

Suppose you can get 1% improvement each week. Over a year that isn’t just more than 50% improvement it is well over 60% improvement – because each 1% is 1% of something bigger than the the previous 1%. Therefore a 1% improvement in week 50 is actually equivalent to 1.6% improvement in week 1.

Here is another spreadsheet where I’ve modelled this.

Suppose you have a team of 5. Suppose the cost $100,000 each per year, thats $500,000 for the team or $10,000 per week (to keep the numbers simple I’m calculating with a 50 week year.)

Now, suppose the team make a 10% value add, i.e. they add 10% more value then they cost, so each year they generate $550,000 of value. That is $11,000 per week.

Next, assume they improve productivity 1% per week. In week one they improve by $110, not much.

Week two they improve by $111, week three $112 and so on.

At this point you are probably thinking: why bother? – even in week 49 the team only add $177 to their total in week 48.

But… these improvements are cumulative. In the last week the team are delivering $6,912 more value than week one: $17,912 of value rather than $11,000. The total annual value added $159,095. That is $11,110 in week one, $11,221 in week two, …. $17,912 in week 47, $17,734 in week 48 and $17,559 in week 49.

The team are now delivering $709,095 value add per year – a 29% increase!

Put it another way: $159,095 is $31,819 per person per year, or $3,181 per week on average, and $636 per person per week.

At first glance this seems crazy: the team are adding 1% extra value per week, even in the last week they only add $177 of extra value compared to the previous week. But taken together over the year the power of accumulation means they are adding over $3,000 per week.

Go back to the start of this piece: you want to convince a budget holder. $177 isn’t even worth their time to talk about it but $3,181is.

Want to buy a book for everyone on the team? $30 per book is $150, do it.

A two hour retrospective? Thats 10 working hours for the whole team, about $2,200, well worth it.

Want to send someone to a 2-day conference, say, $1,000 for a ticket and $4,000 for lost productivity, $5,000 in total. If they come back with one 1% improvement idea then the conference pays for itself in one and a half weeks.

Suppose you invite a speaker from the conference to give a lunch and learn session. Say $1,000 for the speaker and $50 for pizza. If they give the team a 1% idea then it pays for itself that day.

Like it so much you buy a 2-day course? Now your talking big money. Although the $10,000 for the speaker is still less than the cost of having people not work. Five people each on a two day course means 10 days, $20,000 so $30,000 in total. That will take nine and a half weeks of 1% improvements. But then, one might hope that such a course delivers a bit of a bigger boost.

(Is now a good time to plug the agile training I offer? – or is that too blatant a plug?)

The important thing is to make iterate quickly and keep getting 1%, 1%, 1%. There should’t be time for agonising “Is this the best thing we should do?” – “wouldn’t doing X give more improvement than Y?” – just do it! The other ideas will still be good next week.

And don’t worry if it goes wrong. Not every possible improvement will deliver 1%, some will probably go so wrong they damage performance. Just recognise such changes don’t work and quickly back them out.

When you do the numbers it all makes sense.

Now you can call me

November 14, 2017

How much is it worth? – more about money

xx

The post How much is it worth? – more about money appeared first on Allan Kelly Associates.

Allan Kelly's Blog

- Allan Kelly's profile

- 16 followers