Cyndi Norwitz's Blog, page 3

December 29, 2022

Are You Done Yet?

Written Dec 29, 2022

Last updated Dec 29, 2022

Excerpt from Chapter 1 — Passover SederSTEP 1 (Beginning)

Excerpt from Chapter 1 — Passover SederSTEP 1 (Beginning) Come up with a fabulous idea. (2008)

Come up with a fabulous idea. (2008) Do some research and outlines, get all excited. (2008)

Do some research and outlines, get all excited. (2008) Run ideas around in my head over and over, committing little to nothing to paper. (2008-2017)STEP 2 (No, really, now I’m beginning)

Run ideas around in my head over and over, committing little to nothing to paper. (2008-2017)STEP 2 (No, really, now I’m beginning) Join a writer’s group to make me accountable. (2017)

Join a writer’s group to make me accountable. (2017) Really buckle down to write this screenplay, get some software, read some books. (2017)

Really buckle down to write this screenplay, get some software, read some books. (2017) Finally admit I have no idea how to write a screenplay (and what was I thinking, anyway?), take a group member’s advice to write a novel instead. (2017)

Finally admit I have no idea how to write a screenplay (and what was I thinking, anyway?), take a group member’s advice to write a novel instead. (2017) Look for my old outline to get started. Realize I never actually wrote it down, just in my head. Curse. (2017)

Look for my old outline to get started. Realize I never actually wrote it down, just in my head. Curse. (2017) Write a new outline (I can do it!). (2017)

Write a new outline (I can do it!). (2017) Write a chapter or two from the middle of the book. Cause it’s clanging in my head and this is the only way to get some peace. Present to my writer’s group. (2017)STEP 3 (First Draft)

Write a chapter or two from the middle of the book. Cause it’s clanging in my head and this is the only way to get some peace. Present to my writer’s group. (2017)STEP 3 (First Draft) Because I can’t write it as a screenplay but it’s still a movie in my head, I’m going to make an illustrated book. Can I draw? No. But what a great idea, right? (2018)

Because I can’t write it as a screenplay but it’s still a movie in my head, I’m going to make an illustrated book. Can I draw? No. But what a great idea, right? (2018) Junk the illustrated book business and start writing it as a real novel. Go back and fix earlier chapters. (2018)

Junk the illustrated book business and start writing it as a real novel. Go back and fix earlier chapters. (2018) Alright, this novel has a prologue, an epilogue, and 10 chapters in-between. (2018)

Alright, this novel has a prologue, an epilogue, and 10 chapters in-between. (2018) Write. Write more. Keep going. Looks like the book will have 30 chapters now. (2018)

Write. Write more. Keep going. Looks like the book will have 30 chapters now. (2018) Wait, I need to add more earlier chapters. And renumber everything. And edit. (2018)

Wait, I need to add more earlier chapters. And renumber everything. And edit. (2018) Discover StackExchange, find myself endlessly diverted. But get tons of amazing feedback from the stacks Writing, Worldbuilding, and more. Stay with it until it implodes

Discover StackExchange, find myself endlessly diverted. But get tons of amazing feedback from the stacks Writing, Worldbuilding, and more. Stay with it until it implodes  . (2018-2020)

. (2018-2020) Keep going. Break up chapters that are too long and add others so the novel expands like an ever-lengthening tent pole. (2019)

Keep going. Break up chapters that are too long and add others so the novel expands like an ever-lengthening tent pole. (2019) Find myself doing so much research that my spouse begs me to start a blog to keep track of it all. So I do. This blog. Right here. As of 12/29/22, there are 60 published blog posts and 14 drafts of posts I’m still working on. (2019)

Find myself doing so much research that my spouse begs me to start a blog to keep track of it all. So I do. This blog. Right here. As of 12/29/22, there are 60 published blog posts and 14 drafts of posts I’m still working on. (2019) Realize my timeline is wrong and add a few weeks to a section. Move chapters around and do a massive rewrite and restructuring to account for what isn’t a simple change. (2020)

Realize my timeline is wrong and add a few weeks to a section. Move chapters around and do a massive rewrite and restructuring to account for what isn’t a simple change. (2020) Keep going. Add more chapters. Try to remember that writing stuff in my head doesn’t count. (2020-2022)

Keep going. Add more chapters. Try to remember that writing stuff in my head doesn’t count. (2020-2022) Almost to the end! So close I can taste it. Should I buckle down and write a bunch or should I find ways to procrastinate, getting out only one chapter every 6 weeks or so for my writer’s group presentation? Damn. (2022)

Almost to the end! So close I can taste it. Should I buckle down and write a bunch or should I find ways to procrastinate, getting out only one chapter every 6 weeks or so for my writer’s group presentation? Damn. (2022) Wait wait, I’m picking up speed. I finished chapter 79, the second to last chapter!! (2022)

Wait wait, I’m picking up speed. I finished chapter 79, the second to last chapter!! (2022) Okay, chapter 80 needs to be broken into two. I mean three. I mean four. (2022)

Okay, chapter 80 needs to be broken into two. I mean three. I mean four. (2022) Alright, this novel has a prologue, an epilogue, and 83 chapters in-between. AND THEY’RE DONE!!!!! (December 2022)

Alright, this novel has a prologue, an epilogue, and 83 chapters in-between. AND THEY’RE DONE!!!!! (December 2022) Excerpt from Chapter 32 — The Last PlagueSTEP 4 (Second Draft)Go through all the chapters to make sure they’re consistent, in the right voice, etc. Take notes for things to research or check. Delighted to find every chapter in excellent shape, only one of which needs major writing, the rest only minor edits. As of 12/29/22, I’ve worked my way to chapter 78. (2022)Go through all the notes I took from the read-through, plus notes I’ve been keeping for years as needed. (2023)Do the research and make all needed changes. (2023)STEP 5 (Beta Readers, Sensitivity Readers, & Expert Readers)Find my readers and send the draft out. Beta Readers are friends and family willing to give an honest critique to better the book. Sensitivity Readers use their lived experience to help me make sure I’ve got things right when writing about cultures that are not my own. They can be friends or family or paid readers. Experts are expert in a topic I cover and can also be friends, family, or paid readers. (2023)Incorporate all the feedback and make necessary edits. (2023)STEP 6 (Third Draft)Do another read-through. (2023)Copy edit. Using professionals for this step. (2023)STEP 7 (Submit)Send out to agents. (2023)No bites? Send out to smaller publishers that don’t require agents. (2023)STEP 8 (Publish)Have I done this before? No. There are a bunch of tasks here that I can add in later. (202?)STEP 9 (Bask)Ya know, not all the fantasy is in the novel. (202?)

Excerpt from Chapter 32 — The Last PlagueSTEP 4 (Second Draft)Go through all the chapters to make sure they’re consistent, in the right voice, etc. Take notes for things to research or check. Delighted to find every chapter in excellent shape, only one of which needs major writing, the rest only minor edits. As of 12/29/22, I’ve worked my way to chapter 78. (2022)Go through all the notes I took from the read-through, plus notes I’ve been keeping for years as needed. (2023)Do the research and make all needed changes. (2023)STEP 5 (Beta Readers, Sensitivity Readers, & Expert Readers)Find my readers and send the draft out. Beta Readers are friends and family willing to give an honest critique to better the book. Sensitivity Readers use their lived experience to help me make sure I’ve got things right when writing about cultures that are not my own. They can be friends or family or paid readers. Experts are expert in a topic I cover and can also be friends, family, or paid readers. (2023)Incorporate all the feedback and make necessary edits. (2023)STEP 6 (Third Draft)Do another read-through. (2023)Copy edit. Using professionals for this step. (2023)STEP 7 (Submit)Send out to agents. (2023)No bites? Send out to smaller publishers that don’t require agents. (2023)STEP 8 (Publish)Have I done this before? No. There are a bunch of tasks here that I can add in later. (202?)STEP 9 (Bask)Ya know, not all the fantasy is in the novel. (202?)

March 22, 2022

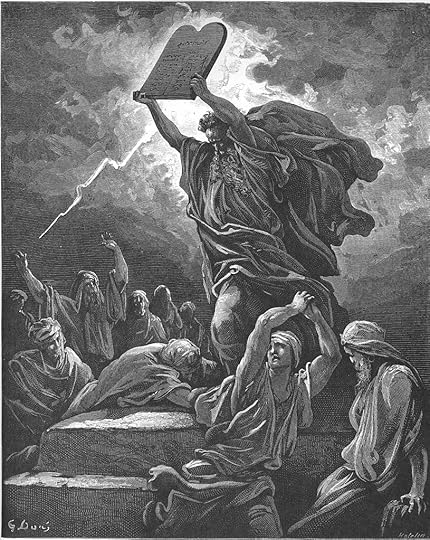

Why Was the Golden Calf So Bad?

The story of the Golden Calf is an odd one, in large part because it’s not clear it ever belonged in Torah at all. It’s really the story of a much later time. Jeroboam, king of Northern Israel around 900 years BCE, erected two golden calves in northern cities with the intention of allowing his subjects to make their religious sacrifices in the north, instead of traveling to Jerusalem in Southern Israel. It’s easy to dismiss both Jeroboam’s and the Exodus-era Hebrews’ sin as idol worship, but that’s not the case.

Most biblical scholars agree that the narrative in Exodus 32 is meant to invoke the story and history of Jeroboam’s two golden calves, at the sanctuaries of Dan and Bethel, as described in 1 Kings 12. Jeroboam’s sin, which dominates the evaluation of the northern kingdom in the books of Kings, and which is said to be responsible for the eventual fall of Israel, is not worship of deities other than YHWH. Jeroboam is condemned primarily for violating the fundamental law of Deuteronomy: the centralization of worship in the one valid sanctuary, the Temple in Jerusalem. As bad as he was, nowhere is Jeroboam accused of leading the Israelites to worship any deity other than YHWH; and if Jeroboam’s golden calves are not idolatry, then the golden calf of Exodus 32, which is modeled after it, shouldn’t be either.

What Was the Sin of the Golden Calf? Prof. Joel Baden. The Torah.com.

What we have in Exodus is a community existing long before the establishment of a settlement in Israel (let alone a temple in Jerusalem and its corresponding rules for worship). If both the explanations of the Golden Calf being idol worship (at least in intention) and breaking the rule of centralized worship in Jerusalem are off the table, what exactly did the Hebrews in Exodus do wrong?

Nicolas Poussin The Adoration of the Golden Calf 1633-4 Oil on canvas, 153.4 x 211.8 cm Bought with a contribution from the Art Fund, 1945 NG5597 https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/NG5597

Nicolas Poussin The Adoration of the Golden Calf 1633-4 Oil on canvas, 153.4 x 211.8 cm Bought with a contribution from the Art Fund, 1945 NG5597 https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/NG5597We have the peripheral wrongs. The Hebrews who coerced Aaron into replacing Moses (their intermediary with God) acted violently. This isn’t actually in Torah at all, though we know that Aaron wasn’t on their side and felt compelled to do as they asked. Many commentators take it as a given that the Hebrews in question murdered Hur in the process, though that’s not in Torah either (neither is the common assertion that Hur was Aaron’s and Moses’ nephew, the son of Miriam and Caleb).

We also know that some of the Hebrews did cross that line and worship the Golden Calf directly.

יהוה spoke to Moses, “Hurry down, for your people, whom you brought out of the land of Egypt, have acted basely.

They have been quick to turn aside from the way that I enjoined upon them. They have made themselves a molten calf and bowed low to it and sacrificed to it, saying: ‘This is your god, O Israel, who brought you out of the land of Egypt!’”

Exodus 32:7-8

Torah though presents the very making of the Golden Calf as a sin. Or HaChaim here breaks down how God explained to Moses the nature of the Hebrews’ mistakes.

G’d had to add particulars about the form this corruption had taken. G’d listed three sins: 1) “they made a golden calf for themselves;” 2) “they prostrated themselves before it and they offered sacrifices to it;” 3) they proclaimed: “these are your gods O Israel, who have brought you out of Egypt.” Israel had therefore sinned in (1) thought, (2) in speech and (3) in deed. G’d first told Moses about Israel having sinned in thought when He said: “they have made for themselves, etc.” This was a sin in thought as long as they had not hailed the calf or sacrificed to it. The critical word is להם, “for themselves.”…Concerning the Israelites’ sin in deed, G’d told Moses that the people had “offered sacrifices to it.” There is no greater act of idol worship than the offering of sacrifices to an idol. Concerning the Israelites having sinned in speech, G’d cited their having said: “these are your gods O Israel, etc.”

Or HaChaim on Exodus 32:8:1.

Or HaChaim goes on to discuss the issue that the Hebrews were worshiping God “wrong.” Making it clear that the problem was not that they turned away from God.

It is also possible that the wording reflects- as I have written previously- that the Israelites retained their full faith in G’d and only saw in the golden calf one of His many manifestations. In view of all this G’d had to make clear that He had not ever commanded something of this nature, i.e. Israel was not allowed to employ intermediaries in their worship of Him and that what happened represented a complete departure from the way G’d had instructed them to relate to Him. This explains why G’d did not speak of Israel in terms of their having rebelled against Him or having denied Him. He was well aware that the Israelites had retained their belief in Him.

Or HaChaim on Exodus 32:8:2.

Ramban wrote centuries before Or HaChaim with similar arguments. He adds:

Aaron saw them set on evil, intent upon making the calf, and he arose and built an altar and proclaimed, Tomorrow shall be a feast to the Eternal, so that they should bring offerings to the Proper Name of G-d upon the altar which he built to His Name, and that they should not build altars to the shameful thing, and that their intent in the offerings should be [to none] save unto the Eternal only.

Ramban on Exodus 32:5.

So making the calf was wrong and shameful, but the Hebrews didn’t really cross the line into evil until they sacrificed animals to the calf itself, an act that entailed worship.

This also is proof to what I have explained [that at first their intent was not to worship idols], since it was not said to Moses, Go, get thee down, for thy people have dealt corruptly. on the day that Aaron made the [golden] calf and the altar, [for had they been made for the purpose of idolatry, Moses] would have come down immediately. Instead, it was only when the people sacrificed to it and worshipped it that He told Moses to go down.

Ramban on Exodus 32:6.

God (and Moses) decries all participation in anything to do with the Golden Calf. Giving up one’s gold jewelry to make the calf with, engaging in revelry the day of the festival, and so on. But God’s punishment was for those who sacrificed and worshiped the calf.

Now most of the people shared in the sin of the incident of the calf, for so it is written, And all the people pulled off the golden pendants. And were it not for this [participation of theirs in the incident], the anger [of G-d] would not have been directed against them to destroy them all. For even though the numbers of those who were killed for this sin: there fell of the people that day about three thousand. and those smitten by G-d. were few [in comparison to the total number of the people, this was because] most of them shared in the sin only in their evil thought [and not in action].

Ramban on Exodus 32:7.

Rashi brings in the idea that the blame for the Golden Calf lies with the mixed multitudes, the non-Hebrews who joined the Hebrews as they left Egypt. Although much of the Torah states that all people who accept God’s commandments or were present at the Revelation, etc, are to be treated the same as those born to the religion, many commentators, before and after Rashi, consider the converts to be the source of any and all trouble, and the reason for any resistance by the people to doing what God had asked of them.

It does not say the people have corrupted but “thy” people — the mixed multitude whom you [Moses] received of your own accord and accepted as proselytes without consulting Me. You thought it a good thing that proselytes should be attached to the Shechina — now they have corrupted themselves and have corrupted others.

Rashi on Exodus 32:7.

Although blaming the converts is a common belief, I find that the trauma of slavery, the terror at being in the desert far from the only home they’d ever known, and the suddenness of a barrage of new rules and laws from a God they barely knew existed a couple months before was enough to explain the Hebrews’ desire for something solid they could point to as their connection with the force that both rescued them and blew up their lives, as well a way to help them know how to move forward.

The last thing on the people’s mind was that Aaron should construct an idolatrous object for them; they did not demand a deity but a leader during their travels in the desert, just as Moses had been their leader. They said this clearly when they told Aaron אשר ילכו לפנינו, “who are to walk ahead of us.” The “leader” was to show them the direction they were to travel in the desert. Up until now Moses had told them what route to take, and now there was no one to tell them in which direction to move.

Rabbeinu Bahya, Shemot 32:8:4.

Rabbeinu Bahya goes on to ask how God chose those who were to die for these acts.

The obvious question is why the people were punished so severely…Why were the Levites allowed to execute 3,000 Israelites? Why did G’d dispatch a plague which killed many of the people?

The answer is simply that whereas the whole episode with the golden calf began innocently enough as an error at worst, as it progressed it turned into deliberate acts of idolatry. This is why the Torah wrote that the people “prostrated themselves before the calf, that they offered peace-offerings to it, that they danced around it, etc.“.

Actually, at that time, the Israelites were divided into different groups. Some of them had pure motives when offering sacrifices…The ones whose motives were idolatrous were the ones of whom the Torah writes: “they prostrated themselves before it, and they slaughtered offerings for it.”

Rabbeinu Bahya, Shemot 32:8:5.

What we’re left with is a collection of wrongs, each coming from a different place and each meriting a different level of punishment. There is no one overarching answer. Nor can we dismiss it all as “they were worshiping an idol.” Any attempt to unify the greater sin of the Golden Calf (whether it be to blame the converts, to say that the Hebrews didn’t worship God exactly as told to, and so on, falls apart when we look more closely.

Instead, we have the complex web that any serious analysis of a historical (or fictional) event would produce. Thousands of people all with different motivations, choices, and understanding of their actions. Some intent on doing evil, others doing it by accident, some with a pure heart throughout, and some crossing the line in the midst of it all.

References:What Was the Sin of the Golden Calf? Prof. Joel Baden. The Torah.com.Jeroboam. Wikipedia.Golden Calf. Wikipedia.The Golden Calf: As commonly understood, this biblical narrative condemns the first violation of the prohibition against idolatry—but it’s not that simple. Dr. Jeffrey Tigay. My Jewish Learning.Or HaChaim on Exodus. Written by Rabbi Hayyim ben Moshe ibn Attar (1696-1743), Moroccan Kabbalist and Talmudist.Ramban on Exodus. Moses ben Maimon, aka Maimonides, a 12th Century Spanish Torah scholar.Rashi on Exodus. Rabbi Shlomo Yitzchaki lived in Troyes, France (1040-1105). Rashi’s commentary is an essential explanation of the Tanakh and resides in a place of honor on the page of almost all editions of the Tanakh. Over 300 supercommentaries have been written to further explain Rashi’s comments on the Torah.Rabbeinu Bahya, Shemot. Bahya ben Asher ibn Halawa, a rabbi and scholar from 13th-14th Century Spain.January 11, 2022

Goldwork for the Golden Calf

Moses said to Aaron, “What did this people do to you that you have brought such great sin upon them?”

Aaron said, “Let not my lord be enraged. You know that this people is bent on evil.

They said to me, ‘Make us a god to lead us; for that man Moses, who brought us from the land of Egypt—we do not know what has happened to him.’

So I said to them, ‘Whoever has gold, take it off!’ They gave it to me and I hurled it into the fire and out came this calf!”

Exodus 32:21-24

When the Hebrews despair of ever seeing Moses again, they coerce Aaron into giving them a substitute, so he makes a calf out of gold. But not even Moses believes his brother’s excuse about a magic fire that turned jewelry into an animal statue. In earlier verses we see Aaron crafting the calf, but it’s not very clear exactly what he’s doing.

And all the people took off the gold rings that were in their ears and brought them to Aaron.

This he took from them and cast in a mold and made it into a molten calf.

Exodus 32:3-4

This is Sefaria’s version but they put in the footnotes that the term “cast in a mold” can also mean “foundry” and that others have translated it as “fashioned it with a graving tool.” Chizkuni describes it in a way translated to English as “he shaped it.”

ויצר אותו, “he shaped it,” the expression יצר, used by the Torah here to describe what Aaron did with the golden jewelry he had received, is based on the word: צרר, “to make a bundle of something, to treat it indiscriminately, or to compress it.”

Chizkuni, Exodus 32:4:1

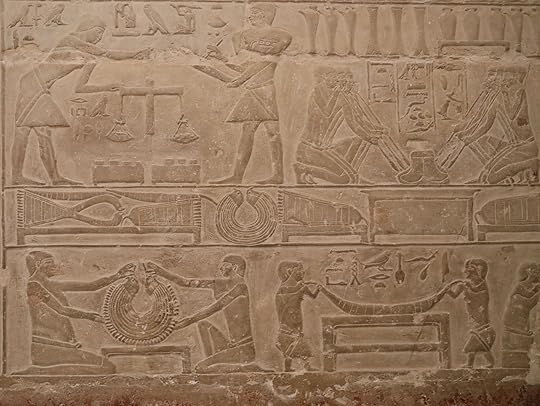

The Goldsmiths. The Tomb of Mereruka. Photo by: Ahmed Romeih – Ministry of Tourism and AntiquitiesCan You Melt It?

The Goldsmiths. The Tomb of Mereruka. Photo by: Ahmed Romeih – Ministry of Tourism and AntiquitiesCan You Melt It?Gold certainly can be melted down then cast with a mold. The problem is that it melts at the very high temperature of 1,948°F (1,064°C) (with slight variations depending on the karat). Most wood cookfires are around 1/3 of that. A large wood fire, a bonfire, can get much hotter. With the right wood and conditions, it can get up to 2,012°F (1,100°C), or just hot enough. Charcoal can burn even hotter. As it happens, the Hebrews roasted a bunch of large animals just before Moses ascended the mountain (almost 40 days earlier) so there should be plenty of charcoal left.

Another problem is there really isn’t that much wood around. Brush yes, not not trees. They’re in an extreme desert at fairly high elevation and any wood they brought is for the mishkan and carts. They might also have bamboo, which they’d use for tent frames, but they might be able to spare some for fires. Both tree wood and bamboo burn much hotter as charcoal.

I see the Hebrews almost exclusively using dried dung as fuel. They have copious amounts of it (with plenty of brush to get the fire going). It’s also something traditionally used in many cultures, including in Egypt.

In Egypt dry animal dung (from cows & buffaloes) is mixed with straw or crop residues to make dry fuel called “Gella” or “Jilla” dung cakes in modern times and “khoroshtof” in medieval times. Ancient Egyptians used the dry animal dung as a source of fuel…Temperatures of dung-fueled fires in an experiment on Egyptian village-made dung cake fuel produced “a maximum of 640°C (1,184°F) in 12 minutes, falling to 240°C (464°F) after 25 minutes and 100°C (212°F) after 46 minutes. These temperatures were obtained without refueling and without bellows etc.”

Dry dung fuel. Wikipedia.

This is not far off from the temperatures one would get from a regular wood fire (a cookfire, not a bonfire). Starting off with a dung fire and then switching to charcoal might actually work to melt gold. Another fuel source is bone, which they’ll also have plenty of in the fire pits after the sacrifices. They seem to burn at similar temperatures to wood.

Forcing AirWhat you’d really want to use though is bellows or blowpipes or something else to increase the temperature. In modern times some people use propane blowtorches and the gold melts in under a minute.

It is possible to reach very high temperatures with very basic technology like blowpipes. Egyptians were melting gold with blowpipes since the early 3rd millennium BC.

An answer from How did ancient civilizations melt gold if gold melts over 1064ºC? Quora. 2019.

A picture from the Old Kingdom (long before the supposed Exodus times) shows six people using blowpipes to keep the gold melting crucible hot enough. While quite impractical compared to bellows or modern equipment, it’s completely doable for a one-time emergency statue such as the Golden Calf.

In the New Kingdom, not long before the time of the Exodus, the Ancient Egyptians were using pot bellows.

Working pot bellows in ancient Egypt, about 1450 BC. BC. By about 1800 BC, Babylonian and Hittite metalworkers were using a pot bellows to smelt copper. You stretched leather over the top of a clay or limestone pot and pulled the leather top up with a string or a stick to fill the pot with air, then stomped on the pot to push the air out into the fire, over and over. A pot bellows turned out to create enough heat so you could smelt iron ore and get usable iron out of it. This same bellows could also be used to melt glass, and almost immediately people in Syria and Lebanon started to use pot bellows to make the first core-formed glass bottles and glass beads. Soon New Kingdom Egyptians were also using pot bellows to smelt metal, and from there they spread slowly to West Africa.

Working pot bellows in ancient Egypt. Quatr.us – Simple History and Science Articles. Facebook. Jan 23, 2018.

Pot bellows from Tomb of Rekhmire, Egypt, ca. 1450 BC.Would the Hebrews Have the Knowledge & Equipment?

Pot bellows from Tomb of Rekhmire, Egypt, ca. 1450 BC.Would the Hebrews Have the Knowledge & Equipment?The short answer is yes. We know they have both because, right after Moses returns with the second set of tablets, they get started on building the Mishkan and the priestly garments. Both of these involve a lot of complex metalwork. They not only had the metal (much of which was given to them by their “neighbors” just before they left Egypt) but they would have brought the tools. We also know that Ancient Egypt had the skills and technology for precious metalwork, including gold, silver, and copper.

Pouring Liquid Gold. Liquid gold being poured into a cast to make a bullion bar at a Gold Reef City demonstration. Even the crucible glows under the immense heat. Dan Brown. January 10, 2006.How Do You Shape It?

Pouring Liquid Gold. Liquid gold being poured into a cast to make a bullion bar at a Gold Reef City demonstration. Even the crucible glows under the immense heat. Dan Brown. January 10, 2006.How Do You Shape It?Gold can be poured into molds, including lost wax casting, something done by the Ancient Egyptians. But honestly, I don’t think that the Golden Calf was very well done. Aaron didn’t want to make it and no one probably wanted to help him, least of all the trained metalworkers among the Hebrews. And there wasn’t time. The Hebrews who threatened Aaron until he agreed to replace Moses weren’t going to wait a year (or even a week) for a piece of art.

The Torah says the Calf was finished the same day that Aaron collected the gold, with a festival the day after. Aaron and whatever helpers he had would most likely melt the gold and pour it into rough molds, then shape it with hammers and other tools and stick it all together. Gold is soft enough that they could possibly even skip the melting step and just pound it.

If the gold is melted, it will cool down fairly quickly, even faster with water. So the timeline works, as long as you don’t mind a crude statue that barely stands on its own. And I think no one minded.

Gold nugget from Australia. (public display, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, Illinois, USA). Nearly four pounds. James St. John. 21 August 2010.References:Chizkuni on Exodus. Hezekiah ben Manoah, French rabbi and Bible commentator of the 13th Century.Gold. Wikipedia.How Hot Is a Bonfire? April 26, 2018. Gabriella Munoz. Sciencing.Dry dung fuel. Wikipedia.How did ancient civilizations melt gold if gold melts over 1064ºC? Quora. 2019.Tomb of Mereruka. At the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities.Metals Used in Metal Sculpture. Weld Guru. June 28, 2021. Jeff Grill.Experiments in Bone Burning. Megan Glazewski, author pp. 17-25. Oshkosh Scholar, Volume I, April 2006.Bellows. Wikipedia.Working pot bellows in ancient Egypt. Quatr.us – Simple History and Science Articles. Facebook. Jan 23, 2018. Plus an article, What is a bellows? Who invented the bellows?

Gold nugget from Australia. (public display, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, Illinois, USA). Nearly four pounds. James St. John. 21 August 2010.References:Chizkuni on Exodus. Hezekiah ben Manoah, French rabbi and Bible commentator of the 13th Century.Gold. Wikipedia.How Hot Is a Bonfire? April 26, 2018. Gabriella Munoz. Sciencing.Dry dung fuel. Wikipedia.How did ancient civilizations melt gold if gold melts over 1064ºC? Quora. 2019.Tomb of Mereruka. At the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities.Metals Used in Metal Sculpture. Weld Guru. June 28, 2021. Jeff Grill.Experiments in Bone Burning. Megan Glazewski, author pp. 17-25. Oshkosh Scholar, Volume I, April 2006.Bellows. Wikipedia.Working pot bellows in ancient Egypt. Quatr.us – Simple History and Science Articles. Facebook. Jan 23, 2018. Plus an article, What is a bellows? Who invented the bellows?

December 28, 2021

Waiting for Moses

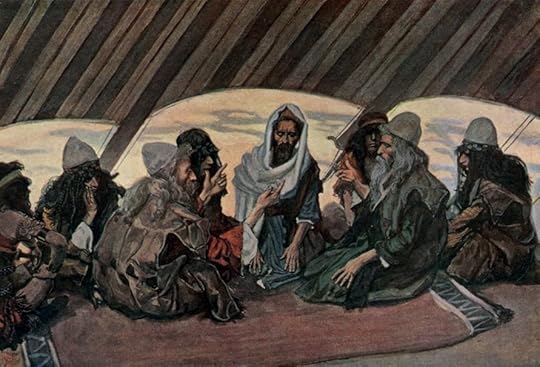

After the Revelation and the sacrifices for the reading of the Covenant, Moses heads up Mount Sinai. For some commentators, he says he will be there for 40 days, for others, he never says. Either way, the people are restless and expect him back already.

Moses on Mount Sinai. Origin: Haarlem. Date: 1703. Jan Luyken, print maker, Noord-Nederlands (1649–1712). Artwork medium etching (paper). Credit Rijksmuseum

Moses on Mount Sinai. Origin: Haarlem. Date: 1703. Jan Luyken, print maker, Noord-Nederlands (1649–1712). Artwork medium etching (paper). Credit RijksmuseumMeanwhile, on the mountain, God prepares Moses for the next task: building the Mishkan (the Tabernacle). First, Moses is to ask the Hebrews for donations.

Tell the Israelite people to bring Me gifts; you shall accept gifts for Me from every person whose heart so moves him.

And these are the gifts that you shall accept from them: gold, silver, and copper;

blue, purple, and crimson yarns, fine linen, goats’ hair;

tanned ram skins, dolphin skins, and acacia wood;

oil for lighting, spices for the anointing oil and for the aromatic incense and other stones for setting, for the ephod and for the breastpiece.

And let them make Me a sanctuary that I may dwell among them.

Exactly as I show you—the pattern of the Tabernacle and the pattern of all its furnishings—so shall you make it.

Exodus 25:2-9

The rest of chapter 25 plus 26 and 27 describe in detail how to build the Ark and the surrounding building. Chapters 28-31 designate Aaron and his four sons as priests and describes how to dress and ordain them, along with a few other things. Chapter 31 ends with God giving Moses the tablets with what we call the Ten Commandments.

When He finished speaking with him on Mount Sinai, He gave Moses the two tablets of the Pact, stone tablets inscribed with the finger of God.

Exodus 31:18

Finally, in chapter 32, we return to the Hebrews waiting at the foot of the mountain for Moses to return.

When the people saw that Moses was so long in coming down from the mountain, the people gathered against Aaron and said to him, “Come, make us a god who shall go before us, for that man Moses, who brought us from the land of Egypt—we do not know what has happened to him.”

Exodus 32:1

Usually modern commentators interpret this as the people wishing to turn their back on God and worship an idol. After all, Egyptians did worship the cow goddess Hathor and the Canaanites worshiped a god El, who could be represented by a bull.

Images of bulls and calves were common in Near Eastern religions. In Egypt, a bull, Apis, was sacred to the god Ptah and emblematic of him. In Canaanite literature, the chief god El is sometimes called a bull, although this may be no more than an epithet signifying strength, and the storm god Baal sires an ox in one myth.

The Golden Calf. Dr. Jeffrey Tigay. My Jewish Learning.

But the sages don’t necessarily see it that way. Chizkuni says:

There is not a single sage that ever suggested that G-d would appoint as a prophet someone who would eventually revert to idolatry. There can therefore be no question that what the people demanded of Aaron was not a return to idolatry. The problem had been that Moses had not announced by what date he would return from the Mountain. The reason that he did not do so was simply that he himself had not known when he would return. G-d had told him that He would give him the Tablets, but had not said when. When the people noticed that Moses took an inordinately long time, far longer than a normal person can go without food or drink, they worried that he might have died, in fact they were convinced that he had. They therefore requested from Aaron that he make for them a replacement whose function would be similar to what had been Moses’ function vis a vis Pharaoh, i.e. elohim…They wanted to replace the Moses the man, not the deity, or semideity.

Chizkuni on Exodus 32:1

Daat Zkenim has similar thoughts.

“make a new Judge for us!” The people saying this to Aaron did not intend for that symbol to be an idol, but to be a supreme judge in lieu of Moses, who they thought had died on the Mountain. This is quite clear from how they justified their request when they said: “for we do not know what has happened to the man Moses, who has brought us out of Egypt.”…When some of them prostrated themselves before that image this also referred to the golden calf as a substitute for Moses, not for G–d. It is not to be understood as idol worship, [although onlookers might have thought so. Ed.]

Daat Zkenim on Exodus 32:1

Or HaChaim agrees but goes one step further, saying the people wanted a visible symbol of God to turn to. I find this odd because God appeared before them as a cloud during the day and a fire at night. The cloud was visible enough to guide them through the wilderness and the fire was strong enough to light their path, even when they traveled at night away from Egyptian roads.

[The people] reasoned as follows: Seeing that G’d Himself who has taken us out of Egypt is invisible and dwells in the Celestial Regions, they were afraid that if they would encounter some evil force in the desert without some visible symbol which reassured them that G’d did indeed watch over them they might lose faith. They wished to construct some symbol of a celestial force which would remind them of G’d in Heaven. The people who initiated the golden calf did not deny for a single moment either the primacy of G’d or the fact that He had made heaven and earth. They merely wanted a go-between them and G’d [similar to when all the people had asked Moses to be their go-between during the revelation at Mount Sinai. Ed.]

Or HaChaim on Exodus 32:1:3

The cloud/fire did not speak but it had volition. When it was time for the Hebrews to move, it moved to let them know to pack up and follow. This is more than the golden calf had. True, the cloud/fire had been mostly in one place for almost two months, now that the Hebrews were settled in their camp at the base of Mount Sinai for a while. But it moved during Revelation and changed as Moses ascended the mountain.

At the time of the making of the Golden Calf, the top of Mount Sinai was on fire.

When Moses had ascended the mountain, the cloud covered the mountain.

The Presence of the LORD abode on Mount Sinai, and the cloud hid it for six days. On the seventh day He called to Moses from the midst of the cloud.

Now the Presence of the LORD appeared in the sight of the Israelites as a consuming fire on the top of the mountain.

Exodus 24:15-17

I don’t think this was just about having a symbol of God to remind them. They already had that. The text says they wanted a judge to take Moses’ place (the highest of the human judges was Moses; after Yitro’s visit, Moses appointed lower level judges to adjudicate most of the cases so he’d only have to take the few that they couldn’t handle).

The Hebrews also couldn’t bear to have God speak to them directly so they wanted a go-between. They had this in Aaron and Miriam though, both prophets in their own right. What would a metal statue add to this? And how could a statue judge anything?

Looking at the various commentaries, it appears that the calf was meant to be a place for God to alight.

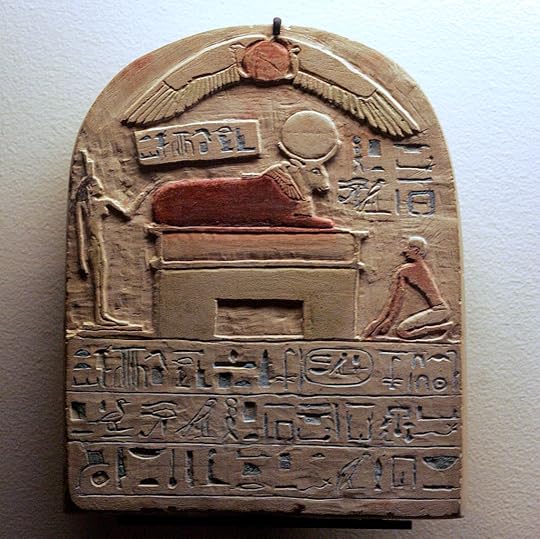

In other words, they did not intend the calf to depict YHVH but to function as the conduit of His presence among them, as Moses had functioned previously. Many scholars believe that the calf did so by serving as the pedestal or mount on which YHVH was invisibly present, as did the cherubs in the Holy of Holies. This conception of the calf is illustrated by ancient images of a god standing on the back of a bull or another animal.

The Golden Calf. Dr. Jeffrey Tigay. My Jewish Learning.

Stele dedicated by the doorman of Horudja temple to the God-bull Apis. Year 21 of Psamtik I, 643 BCE. Painted limestone. Louvre Museum. Found at the Serapeum of Saqqara.

Stele dedicated by the doorman of Horudja temple to the God-bull Apis. Year 21 of Psamtik I, 643 BCE. Painted limestone. Louvre Museum. Found at the Serapeum of Saqqara.The irony is that at that moment (the 40 days Moses was gone) God was giving Moses instructions for creating the very same device.

And deposit in the Ark [the tablets of] the Pact which I will give you.

You shall make a cover of pure gold, two and a half cubits long and a cubit and a half wide.

Make two cherubim of gold—make them of hammered work—at the two ends of the cover.

Make one cherub at one end and the other cherub at the other end; of one piece with the cover shall you make the cherubim at its two ends.

The cherubim shall have their wings spread out above, shielding the cover with their wings. They shall confront each other, the faces of the cherubim being turned toward the cover.

Place the cover on top of the Ark, after depositing inside the Ark the Pact that I will give you.

There I will meet with you, and I will impart to you—from above the cover, from between the two cherubim that are on top of the Ark of the Pact—all that I will command you concerning the Israelite people.

Exodus 25:16-22

The difference, as Dr. Tigay points out, is that the Ark will be inside the Mishkan and not accessible to everyone, but the Golden Calf was for all the people who wished to approach it. Is this about taking back power from self-appointed leaders? (something stated directly through much of the Exodus story) Or about resisting the temptation to turn the conduit into an idol, something to be worshiped directly?

References:Chizkuni on Exodus. Hezekiah ben Manoah, French rabbi and Bible commentator of the 13th Century.Daat Zkenim on Exodus. Torah commentary compiled by later generations of scholars from the writings of the Franco-German school in the 12th-13th century (Ba’alei Tosafot).Or HaChaim on Exodus. Written by Rabbi Hayyim ben Moshe ibn Attar (1696-1743), Moroccan Kabbalist and Talmudist.Pillars of fire and cloud. Wikipedia.Why Moses’s brother worshipped a golden calf: Although Aaron induced plagues against Pharaoh, his weak faith led to the death of 3,000 men and the destruction of the original Ten Commandments. Jean-Pierre Isbouts. National Geographic.The Golden Calf: As commonly understood, this biblical narrative condemns the first violation of the prohibition against idolatry–but it’s not that simple. Dr. Jeffrey Tigay. My Jewish Learning.Inside the Ancient Bull Cult: King Minos and the Minotaur remain shrouded in mystery and mythology, yet evidence of a Bronze Age ‘Bull Cult’ at the Minoan palaces abounds. Were bulls merely for entertainment or did they have a deeper significance? Richard Harrison. 10 Jul 2019. History Today.Apis. Joshua J. Mark. 21 April 2017. World History Encyclopedia.November 1, 2021

The Daily Grind

Once you have dehulled grain, the next step is to grind it. In Ancient Egypt, this would be done by hand, on grinding stones. Not the large mortar and pestles used standing for dehulling (or for mashing other materials), but specialized stones.

When modern researchers try to duplicate ancient techniques, it can be problematic at best.

It was possible to get emmer flour, but I decided to go with the actual grain to get a more accurate result. I didn’t need to remove the husk because it was already processed. The grain was small, darker than regular wheat, and really hard. I started working with a kitchen mortar and pestle, most likely a similar to one used by an Egyptian woman.

I started grinding the grain while I was sitting in front of the TV. It took me a couple of hours and by the end my arms were aching. It was a tiring and time-consuming process. I worked with just a handful of grains at a time, hitting and grinding the grain, and trying to find the best technique. First, I tried cracking the grain, then grinding on the sides of the mortar. Finally, I decided to try a combination of hitting and grinding for finer results.

The result was a coarse flour with some bigger pieces. I tried to cheat using a coffee grinder, but the result was surprisingly similar. Without an actual milling machine, I don’t think it’s possible to get a really fine flour. I couldn’t imagine how the Egyptians managed to get a finer result using traditional tools.

Ancient Egyptian Bread, by Miguel Esquirol Rios. The Historical Cooking Project. December 10, 2014.

A mortar and pestle isn’t the right tool for grinding grain. Ancient Egyptians used them for de-hulling grain, among other things. For actual grinding, they used a saddle quern.

Some saddle quern grinding is done standing up.

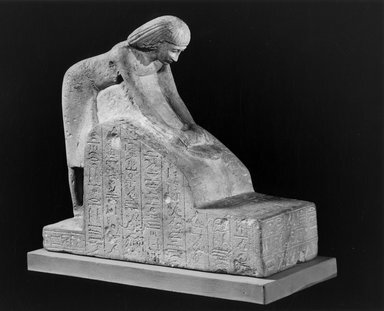

Senenu Grinding Grain, Egyptian, Classical, Ancient Near Eastern Art. Brooklyn Museum, New York, Martha A. and Robert S. Rubin Gallery. The royal scribe Senenu appears here bent over a large grinding stone. ca. 1352-1336 B.C.E. or ca. 1322-1319 B.C.E. or ca. 1319-1292 B.C.E., late Dynasty 18, New Kingdom.

Senenu Grinding Grain, Egyptian, Classical, Ancient Near Eastern Art. Brooklyn Museum, New York, Martha A. and Robert S. Rubin Gallery. The royal scribe Senenu appears here bent over a large grinding stone. ca. 1352-1336 B.C.E. or ca. 1322-1319 B.C.E. or ca. 1319-1292 B.C.E., late Dynasty 18, New Kingdom.And some is done kneeling.

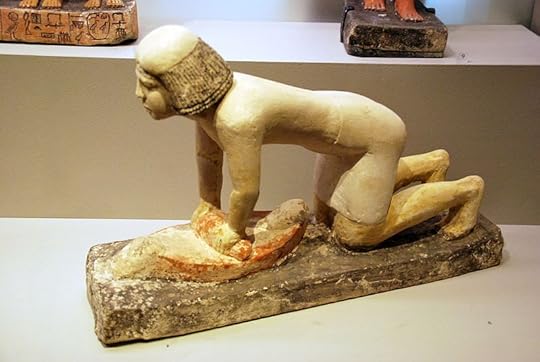

Statuette of a woman grinding grain; Limestone; from Giza, Egypt (G 2415), found in 1921; mid- to late Dynasty 5 (reigns of Niussera to Unis, 2420-2323 B.C.); acc. 21.2601. Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

Statuette of a woman grinding grain; Limestone; from Giza, Egypt (G 2415), found in 1921; mid- to late Dynasty 5 (reigns of Niussera to Unis, 2420-2323 B.C.); acc. 21.2601. Boston Museum of Fine Arts.Models of the Palace bakery show women doing the grinding, and household grinding was probably the same. Many of the statues, like the two above, show men doing this work (never mind that one of the photographers seems confused).

A quern is a grinding stone and they’ve been around for at least ten thousand years.

Prior to the invention of the rotary quern, perhaps in north-eastern Spain about the fifth century BC, all grinding was undertaken by rubbing a hand held handstone against a larger base stone. The base stone could take a range of forms, and there is a correspondingly wide terminology for them. In Pharaonic Egypt, the cereal grinding quern was a more or less flat or somewhat curved stone, longer than wide, and with a roughened surface, on which a handstone was rubbed back and forth over the long axis to pulverise the grains, and is also known as a saddle quern.

Experimental Grinding and Ancient Egyptian Flour Production. Delwen Samuel. King’s College London, Nutritional Sciences Division. January 2010.

Saddle Quern and Rubbing Stone. Early Neolithic (3700 – 3500 BC). Etton, Cambridgeshire, England.

Saddle Quern and Rubbing Stone. Early Neolithic (3700 – 3500 BC). Etton, Cambridgeshire, England.The basic floor model is less efficient and not the style that the characters in my book, which takes place during the New Kingdom, would have used.

Throughout the Old Kingdom, statuettes and tomb paintings that illustrate the grinding process all show the millers kneeling on the ground; there are many other examples). By the Middle Kingdom millers are shown working at querns placed on raised platforms…According to the artistic record, by the Middle Kingdom the quern raised on an emplacement was a standard installation throughout Egypt….The querns were made from granite or quartzitic sandstone.

Experimental Grinding and Ancient Egyptian Flour Production. Delwen Samuel. King’s College London, Nutritional Sciences Division. January 2010.

And:

Next, the the whole grain was milled into flour, usually using a flat grinding stone known as a saddle quern. From Neolithic times through the Old Kingdom, these grinding stones were placed on the floor, which made the process difficult. However, tombs scenes of the Middle Kingdom show the querns raised onto platforms, called quern emplacements. Some of these have been excavated at a few New Kingdom sites. They made life much easier, and probably made the work quicker as well. Modern experimentation with these devices has shown that no grit was required to aid the milling process, as has sometimes been suggested by scholars, and the the texture of the flour could be precisely controlled by the miller.

Bread in Ancient Egypt. Tour Egypt. By Jane Howard. August 21st, 2011.

Delwen Samuel’s research is amazing and detailed. She not only delves into the history and the archeological record, but she uses ancient tools (mostly replicas) to show how this work actually happened. Here she is practicing the grinding of emmer into flour.

What does saddle quern grinding looks like?One [10 g] batch at a time was placed on the surface of the quern and the handstone was passed firmly ten times over the grain. One ‘pass’ consisted of the handstone pushed from the end of the base stone closest to the miller, across the length of the stone to the other end, and back again…The resulting meal was carefully swept off the surfaces of the quern and handstone with a brush onto a tray, and the process repeated with another batch until the whole sample had been ground. Fine meal was produced by repeating the coarse milling process…Each of these coarse meal batches was ground with 20 passes of the handstone over the saddle stone (30 passes in total)….

Breaking the whole grains into coarse particles was the most difficult stage of the milling process. When the grains are whole, they present a relatively smooth, rounded surface which slides over the slightly roughened surface of the saddle stone and which is difficult to grip with the rounded surface of the handstone. The initial few strokes required very firm pressure and had to be done slowly, but once completed the grains began to fracture and break. As soon as some irregular grain fragments were produced, along with the exposure of the more easily abraded inner grain (the starchy endosperm), it became quicker to grind but firm pressure was still needed….

A more effective method is to work at the edge of a pile of grains, cracking the outer grains to large fragments and exposing the starchy endosperm. The irregular pieces ‘stick’ onto the rough stone much better than the smooth rounded whole grains and also allow the handstone to grip the adjoining whole grains so that they can be quickly cracked. Once some of the whole grain is reduced to coarse fragments in this fashion, it is easy to mill across increasingly larger areas of the quern surface. The initial ‘cracking’ stage is quite rapid. Using this more effective method, it is possible on this size of quern to mill much more than 10 g of grain at a time to a coarse or a fine meal.

Experimental Grinding and Ancient Egyptian Flour Production. Delwen Samuel. King’s College London, Nutritional Sciences Division. January 2010.

Video of grinding with a saddle quern. Nick Roberson, Roberson Stone Carving.

Ancient Ireland Grain Processing Quern Stones 101. Start at 1:25 for saddle quern grinding demonstration.

It’s not particularly difficult when in a comfortable standing position (and in these videos the angles don’t look optimized; the querns are horizontal and on a modern table or counter, vs. angled down to allow gravity to add to the grinding power) and the experienced video subjects (who do demos regularly but don’t live in communities where this is how they prepare their food) seem to get mixed size flour in about a half dozen passes; I’d guess another half dozen would give more uniformly fine flour, for a total of 12 passes vs. Samuel’s 30 pass total.

How long does grinding take?During earlier grinding experiments with a replica New Kingdom quern emplacement, an authentic ancient Egyptian saddle quern and a small ancient basalt handstone, I took just under two hours to grind 1.2 kg of emmer grain. This is the same as or longer than for my ground-based milling experiments.

…It seems reasonable to estimate that in ancient Egypt, milling flour on the ground for domestic production might have taken about three hours a day.

Experimental Grinding and Ancient Egyptian Flour Production. Delwen Samuel. King’s College London, Nutritional Sciences Division. • January 2010.

With a raised platform saddle quern and strong experienced grinders, let’s say we can do one kilogram per hour. Our large household in the novel uses 89 lbs of emmer grain each day. Five of those pounds go into porridge. Porridge can be made with whole grains or cracked ones. Either way, you’re not making flour.

So 85 lbs of grain = 38.5 kg. Or 38.5 hours of work. A day. But that’s only slightly better than what an inexperienced researcher did without the extraordinary upper body strength of someone who does this daily. I’m going to double the production rate. That fits as well with very rough estimates from videos.

So about 19 hours a day for grinding. If the household has four raised saddle querns then each one is in use for nearly five hours. That works well with a large kitchen where most of the adults pop in here and there to take turns grinding (and also de-hulling).

References:Ancient Egyptian Bread, by Miguel Esquirol Rios. The Historical Cooking Project. December 10, 2014.Quern-stone. Wikipedia.Model Bakery and Brewery from the Tomb of Meketre, ca. 1981–1975 B.C., Middle Kingdom. On view at The Met Fifth Avenue in Gallery 105.Experimental Grinding and Ancient Egyptian Flour Production. Delwen Samuel. King’s College London, Nutritional Sciences Division. January 2010.A new look at old bread: ancient Egyptian baking. November 1999, Archaeology International 3, Delwen Samuel, St Mary’s University, Twickenham.Bread in Ancient Egypt. Tour Egypt. By Jane Howard. August 21st, 2011.Saddle Quern Stones. Nick Roberson, Roberson Stone Carving. Includes a video of the grinding process.Who made bread and how at Amarna? By Delwen Samuel. Akhetaten Sun 19(2): 2-7. 2013.October 16, 2021

The Female God

Before he dies, Jacob blesses each of his sons. In the blessing for Joseph, we have some unusual language.

The God of your father who helps you,

And Shaddai who blesses you

With blessings of heaven above,

Blessings of the deep that couches below,

Blessings of the breast and womb.

Genesis 49:25

Most of the commentators (who are male) interpret this, unsurprisingly, as blessings for those things (not those people) which allow the nation to grow in population.

The breasts are blessed at which thou wast suckled, and the womb in which thou didst lie.

Targum Jonathan on Genesis 49:25

Some are even more oblique.

Jacob likened the breasts to heaven and the womb to the earth, its meaning being that Joseph will be blessed with many children. (Footnote: Our verse reads, With blessings of heaven…Blessings of the deep…Blessings of the breasts, and of the womb. According to I.E. breast and womb are similar to heaven and earth in that they produce life-giving substance and bring forth fruit. Hence they are included in the same verse.)

Ibn Ezra on Genesis 49:25:3

Are these not blessings of a Mother God? Could there be anything coded more strongly as female than milk-giving breasts and a life-giving womb? How exactly do breasts and wombs get added to the many offerings of a Father God?

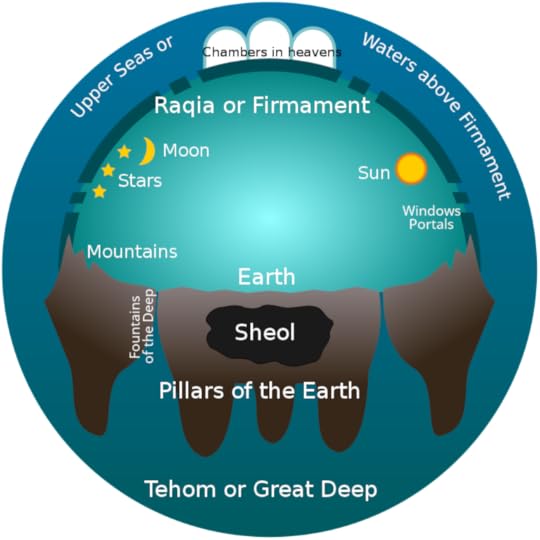

In the other part of the blessing, the blessings of the deep (tehom), the commentators even tell us the deep is feminine. Though somehow they only mean it grammatically (and even then, only sometimes).

The word tehom (the deep) is feminine both in our verse and in Deut. (33:16). It is similarly feminine in The deep (tehom) made it to grow (Ezek. 31:4). The meaning of With blessings of heaven above, Blessings of the deep that coucheth beneath is that rain will descend from the heavens above upon the land of Joseph and that the deep which coucheth beneath the earth will fill its rivers and springs with an abundance of water. (Footnote: Our verse reads, tehom rovetzet (the deep that coucheth). Deut. 33:13 reads, u-mi-tehom rovetzet (and for the deep that coucheth). Rovetzet (coucheth) is feminine, hence tehom (the deep) must be feminine. Ezek. 31:4 reads, tehom romematehu (the deep made it to grow). Since romematehu is feminine, tehom, too, must be feminine. I.E. makes this point because tehom is masculine in Ps. 42:8. Thus we see that tehom is both masculine and feminine.)

Ibn Ezra on Genesis 49:25:2

Early Hebrew Conception of the Universe. Tom Lemmens. 13 February 2021.

Early Hebrew Conception of the Universe. Tom Lemmens. 13 February 2021.What is tehom, the deep? Beyond the mere surface water of irrigation and hydration.

This endless ocean already exists before Creation even starts, and Torah doesn’t explain how it got there. It is primordial, powerful; it rivals God for primacy. This is the water of the Flood. Forty days of rain are nasty, but the destruction comes from the unchaining of the previously subdued Deep. It is the pre-Creation order coming to reclaim its place.

On the Sea. Itzik’s Well. Rabbi Irwin Keller. October 9, 2021.

We see tehom as well with the parting of the Red Sea and in Jonah. All stories where the actors or main players are male. I don’t find a single reference (but surely there are some) that gives tehom as the source of Miriam’s well. But how could it be otherwise? If tehom is what fills rivers and springs, is it not what supplies the endless well Miriam brings forth in the wilderness? Enough water to supply tens of thousands of people, plus cattle and other livestock. Enough to drink and bathe and purify for nearly 40 years.

Tehom is living water. Water that moves from the depths. A womb also holds living water, the amniotic fluid. Breastmilk is living water as well.

I won’t quibble over what is male vs female because, in my mind, God has no gender (or all gender) anyway. Despite the masculinization of God in this narrative (though it’s often Elohim, or Gods instead of God), the reality is that it describes a God which is both male and female (and presumably every other gender).

And God created man in His image, in the image of God He created him; male and female He created them.

Genesis 1:27

The problem isn’t assigning some things which sustain life—womb/earth, breasts/heaven, water/tehom—to a masculine God. It’s that our culture, both the authors of the Bible and the commentators/readers through to the modern age, assign everything to God as male. The female has been systematically erased.

There is so much more I could say. From the amazing course on the Sacred Feminine in Judaism on offer from my synagogue to the scholarship of countless women and others opening my eyes to the female God in front of me. But I’m not writing a dissertation. I’m only looking at how my travelers would have experienced the Exodus. Its fullness, its reality. Its connection to God and spirit before the codification of Torah many centuries later.

Arial view of Bhorley waterfall of Dolakha and Tamakoshi river. This is a photo of a natural site in Nepal identified by the ID Gaurishankar Conservation Area. 18 October 2018. Nammy Hang Kirat.References:Targum Jonathan on Genesis. Primary Targum on the books of the Prophets, read publicly in synagogues in talmudic times and still today by Yemenite Jews. Targum (“translation”) is the name of a category of texts that translate the Tanakh into Aramaic, originally transmitted orally and committed to writing between the 1st and 6th centuries CE.Ibn Ezra on Genesis. Abraham ben Meir Ibn Ezra, a 12th Century Biblical commentator from Spain.On the Sea. Itzik’s Well. Rabbi Irwin Keller. October 9, 2021.Tehom. Wikipedia.

Arial view of Bhorley waterfall of Dolakha and Tamakoshi river. This is a photo of a natural site in Nepal identified by the ID Gaurishankar Conservation Area. 18 October 2018. Nammy Hang Kirat.References:Targum Jonathan on Genesis. Primary Targum on the books of the Prophets, read publicly in synagogues in talmudic times and still today by Yemenite Jews. Targum (“translation”) is the name of a category of texts that translate the Tanakh into Aramaic, originally transmitted orally and committed to writing between the 1st and 6th centuries CE.Ibn Ezra on Genesis. Abraham ben Meir Ibn Ezra, a 12th Century Biblical commentator from Spain.On the Sea. Itzik’s Well. Rabbi Irwin Keller. October 9, 2021.Tehom. Wikipedia.

October 7, 2021

Threshing & Hulling Emmer

Emmer is an old variety of wheat (and a Farro grain) grown extensively in the ancient world, including by Ancient Egyptians.

The four wild species of wheat, along with the domesticated varieties einkorn, emmer and spelt, have hulls. This more primitive morphology (in evolutionary terms) consists of toughened glumes that tightly enclose the grains, and (in domesticated wheats) a semi-brittle rachis that breaks easily on threshing. The result is that when threshed, the wheat ear breaks up into spikelets. To obtain the grain, further processing, such as milling or pounding, is needed to remove the hulls or husks. In contrast, in free-threshing (or naked) forms such as durum wheat and common wheat, the glumes are fragile and the rachis tough. On threshing, the chaff breaks up, releasing the grains. Hulled wheats are often stored as spikelets because the toughened glumes give good protection against pests of stored grain.

Wheat. Wikipedia.

Emmer spikelets Triticum turgidum subsp. dicoccum. POACEAE or Triticum dicoccon. Cultivar name: KHAPLI. Collected in: Madhya Pradesh, India, 1926

Emmer spikelets Triticum turgidum subsp. dicoccum. POACEAE or Triticum dicoccon. Cultivar name: KHAPLI. Collected in: Madhya Pradesh, India, 1926Functionally, this means that, with modern day wheat, one threshes the grain (beats it to release the seeds) then winnows it (separates chaff from seed by using the wind or throwing it in the air). But with emmer, there is an extra step in-between the two of removing the seed from the chaff.

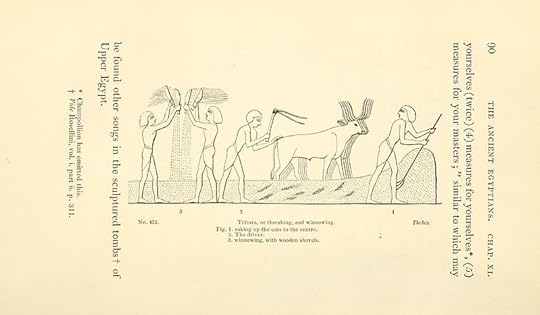

A second series of the Manners and customs of the ancient Egyptians (Page 90). John Gardner Wilkinson.

A second series of the Manners and customs of the ancient Egyptians (Page 90). John Gardner Wilkinson.The steps to creating usable emmer grain are as follows:Harvest. Gather and dry in the fields 7-10 days.Thresh.Store grain with hulls/spikelets to prevent pests.De-hull (de-chaff) by wetting and pounding/rubbing.Dry.Run through sieve to free grain.Winnow (throw grain from one container to another on a day with light wind so the loose chaff blows away).Soak for porridge or grind for bread.In many areas where emmer was grown, the chaff was removed by pounding the spikelets in wooden or stone mortars with wooden pestles or mallets. The key to the process is wetting the spikelets first. The damp chaff becomes pliable and slightly sticky. Thus, when the spikelets are pounded, they are rubbed vigorously together rather than crushed. The chaff can become quite flexible and the grain can pop out of the spikelet under the pressure of pounding. The pounding causes the chaff to shear apart and release the grain. Once the damp chaff and grain mixture is dried, the chaff can be sieved and winnowed to separate it from the grain.

A new look at old bread: ancient Egyptian baking. November 1999. Samuel Delwen.

Samuel discusses archeological findings of shallow stone mortars and wooden pestles, with plant remains to prove they were used for de-husking emmer. While my book has a communal kitchen for one large family group (about 55 people), archeology shows that, in Ancient Egypt, people were more likely to have smaller mortars and pestles with one installed in each household.

Mortar and pestle for two people in Guinea

Mortar and pestle for two people in GuineaWhether we want to explain this by the fact that they were slaves and had huts instead of houses, that they were a separate ethnic group, or poetic license, I’m going to assume this large outdoor kitchen had more than one mortar and pestle. The author photographed some in Turkey with an inner diameter of perhaps 3 feet. But the Egyptian one is low to the ground with about 10 inches for an inner diameter and made of limestone with mudbricks and a plastic rim. Sieves were made from wood and grass.

These smaller mortars process about a pound of grain at a time, which the author tried himself and reports that it “does not take long.” The pestle is very tall and thick and one uses it while standing upright. A larger family would need a bigger mortar to de-husk the 89 lbs of emmer I estimate they would use each day. And might want it to be deeper as well, to better contain the grain.

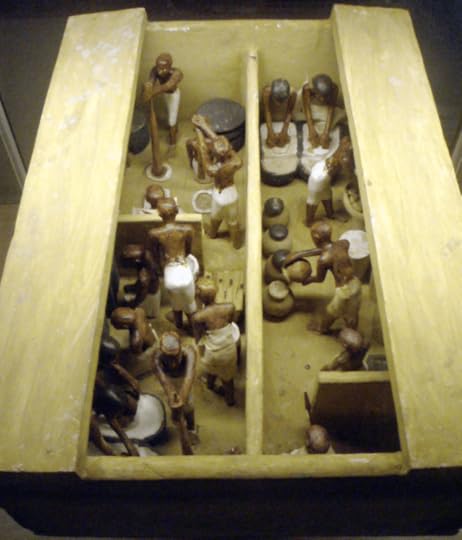

Ancient Egyptian drawings and models from the Middle Kingdom represent larger, fancier operations. Either the palace kitchens or bakeries. They tend to use these smaller mortars but have more than one. They are in the back left of this model.

Model Bakery and Brewery from the Tomb of Meketre

Model Bakery and Brewery from the Tomb of MeketreA funerary model of a bakery and brewery, dating the 11th dynasty, circa 2009-1998 B.C. Painted and gessoed wood, originally from Thebes.

Videos of modern day usage of mortar and pestles like these seem to indicate perhaps 2-5 minutes to de-hull a pound or so of grain. One video shows 3 women pounding a raised, slightly larger, mortar. Another shows a single woman using a raised mortar and a skinny pestle. This could mean it would take as long as 2.6 to 7.5 hours to de-hull a day’s worth of grain (which I estimate as around 89 pounds of grain). Plus another 1-2 hours to sieve and winnow it. This video shows pounding and winnowing rice, which goes faster because there is no need to wet the rice first.

Let’s assume that the kitchen has at least two mortars. As the strongest workers get up in the morning and prepare to go to work, they take turns de-hulling. If 4 of them each spend half an hour (2 hours in real time), and we say they’re very efficient, that could be enough for the day’s grain.

Sieving and winnowing may have been done as one task.

[Seated] on the ground with her feet spread widely apart, taking in her hands a large but shallow sieve called ghurbal, some two and a half feet across [The Arabic word is ghurbal, the Hebrew word is kebarah (כְּבָרָה)]. [Using] a small amount of wheat…she commences by giving it some six or seven sharp shakes, so as to bring the chaff and short pieces of crushed straw to the surface, the greater part of which she removes with her hands…Holding the sieve in a slanting position, she jerks it up and down for a length of time, blowing across the top of it all the while with great force…Three results follow. In the first place the dust, earth, small seeds, and small, imperfect grains of wheat, etc., fall away through the meshes of the sieve. Secondly, by means of the vigorous blowing, any crushed straw, chaff, and such-like light refuse is either blown away to the ground, or else collected in the part of the ghurbal which is furthest from her. Thirdly, the good wheat goes together in one heap about the center of the sieve, while the tiny stones or pebbles are brought into a separate little pile on that part of it which is nearest to her chest. The pebbles, chaff, and crushed straw thus cleverly removed from the corn [grain], mainly by the angle at which the sieve is held and the way in which it is jerked up and down, are then taken out of the ghurbal with her hands. Finally, setting the sieve down upon her lap, she carefully picks out with her finger any slight impurities which may yet remain, and the elaborate and searching process of sifting is complete.

Peeps Into Palestine: Strange Scenes in the Unchanging Land Illustrative of the Ever-Living Book. James Neil. London. c. 1915.

Sieve/Winnowing Tray. “A large sieve with a wooden rim and a mesh of plaited leather thongs. Such sieves are used in winnowing, the grain being first tossed into the air with a fork, then sieved.” From Upper Egypt, purchased in a market in the 1920’s. CC license from British Museum.How long does it take to process wheat?

Sieve/Winnowing Tray. “A large sieve with a wooden rim and a mesh of plaited leather thongs. Such sieves are used in winnowing, the grain being first tossed into the air with a fork, then sieved.” From Upper Egypt, purchased in a market in the 1920’s. CC license from British Museum.How long does it take to process wheat?If we assume our extended family group of about 75 people needs 89 pounds of grain a day (32,485 pounds per year), how many work hours a day need to be allotted to process it into clean whole grain?

Threshing is not terribly time consuming, at least not in comparison with the overall harvest. This harvest took place in the spring before the start of my story. While the barley and emmer harvests should have been in April and May, when my characters are in Egypt, the hail destroyed the former and the locusts the latter. There is no harvest; they’re relying on stocks from the previous year.

In Ancient Rome, an acre of wheat yielded 7.5-22.5 bushels of grain (about 450-1350 pounds). Given that Ancient Egypt is over 1000 years earlier and that emmer is lower yielding than more modern wheat, we’re probably looking at around 10 bushels per acre (600 pounds), enough for about 500 people, which means the labor for planting, harvest, and threshing is shared across households. After allowing for the weight difference of threshed vs cleaned grain (that 600 lbs per acre turns into 400 lbs clean grain) it seems my family unit needs around 81 acres of wheat fields planted each year.

An adult with a flail on a threshing floor could thresh 7 bushels (420 lbs) of wheat a day. That’s 77 full days of work to create the needed 32.5K lbs for 75 people. Now, my family group is actually only 55 people and the extra 18 (I was rounding to 75) weren’t there very long. So it’s really only 57 work days to thresh enough for the family.

Harvest and post-harvest would be a busy time so assume all hands on deck. Threshing could easily be done in a week, including time to process plenty of grain for Pharaoh, as part of their work quotas.

All of that’s already done though. The threshed grain is sitting in storehouses in the family compound, and in other areas to be brought in as needed. The chaff keeps pests away (an advantage of these older wheat varieties).

De-hulling aka de-chaffing can be done daily or weekly, it doesn’t matter, as whole grain won’t spoil quickly.

ReferencesWheat. Wikipedia.Emmer. Wikipedia.A new look at old bread: ancient Egyptian baking. November 1999, Archaeology International 3. Samuel Delwen. St Mary’s University, Twickenham.Mortar and pestle. Wikipedia.Peeps Into Palestine: Strange Scenes in the Unchanging Land Illustrative of the Ever-Living Book. James Neil. London. c. 1915. (Excerpt taken from Spirit and Truth Online.)Roman Foodstuffs: Part 3. Aquila Nova Roma.Crop residue. Shilo Andrews. August 26, 2005. Vulcan County. Vulcan, Alberta, Canada. Grain Harvest and Threshing Time. Living History Farms. July 28, 2015.September 22, 2021

The Sacrifices Between Revelation and Ascension

The day after the Revelation of Sinai (the day God gave the Torah to the children of Israel), Moses leaves to go to the top of Mount Sinai for 40 days. His goal: to bring back the tablets with the ten sayings, what many call the Ten Commandments.

Before he does, he presides over a great sacrifice of animals and delivers the Covenant.

Who are these young men?

Moses then wrote down all the commands of the LORD.

Early in the morning, he set up an altar at the foot of the mountain, with twelve pillars for the twelve tribes of Israel.

He designated some young men among the Israelites, and they offered burnt offerings and sacrificed bulls as offerings of well-being to the LORD.

Moses took one part of the blood and put it in basins, and the other part of the blood he dashed against the altar.

Then he took the record of the covenant and read it aloud to the people. And they said, “All that the LORD has spoken we will faithfully do!”

Moses took the blood and dashed it on the people and said, “This is the blood of the covenant that the LORD now makes with you concerning all these commands.”

Exodus 24:4-8

Ibn Ezra says the were “the sons of the chosen elders who were to go up on the mountain with Moses.” Chizkuni says they were “young lads on the threshold of becoming of age when they would be eligible to observe the commandments. According to a different view, these were all firstborns of their respective families.”

Rabbeinu Bahya and others further elaborate that these are young men who had never had sex with a woman. Ramban and others reiterate that the men are first borns.

Which animals for the offerings?There are two types of offerings here (there are other types described in other places): burnt offerings and offerings of well-being.

Burnt offerings are a tribute to God burnt entirely on the altar. The skins, however, are saved and given to the priests. They are usually sheep (or lambs) or goats (or kids).

These were wholly animal, and the victims were wholly consumed. They might be from the herd or the flock, or in cases of poverty birds might be substituted. The offerings acceptable were: (a) young bullocks; (b) rams or goats of the first year; (c) turtle-doves or young pigeons. These animals were to be free from all disease or blemish. They were to be brought to the door of the tabernacle, and the offerer was to kill them on the north side of the altar (if a burnt offering), except in the public sacrifices, when the priest put the victims to death, being assisted on occasion by the Levites…The blood was then sprinkled around the altar. The victim, if a large animal, was flayed and divided; the pieces being placed above the wood on the altar, the skin only being left to the priest. If the offering was a bird a similar operation was performed, except that the victim was not entirely divided. The fire which consumed the offerings was never allowed to go out, since they were slowly consumed; and the several kinds of sacrifice furnished constant material for the flames. Every morning the ashes were conveyed by the priest to a clean place outside the camp.

Burnt Offering. Morris Jastrow, Jr., J. Frederic McCurdy, Kaufmann Kohler, Louis Ginzberg. 1906 Jewish Encyclopedia.

Offerings of well-being, also called peace-offerings, were often bulls and were eaten by all (as opposed to sin offerings which were usually for the Priests alone).

How many animals?“…as feast peace-offerings for Hashem, bulls.” As long as the Israelites were in the desert they always experienced some fear of the attribute of Justice seeing they found themselves in a part of the earth which was desolate, reflected destruction of nature, etc. This is why they slaughtered bulls as their offerings [the standard sin-offering of High Priests, or the communal sin-offering for the whole people when the occasion demanded it. Ed.].

Rabbeinu Bahya, Shemot 24:5:4

We know the offerings of well-being were bulls, because it says so in Torah. We don’t know which animal they used for the burnt offerings, but I’m assuming it was sheep. Now the question is, how many?

Because of the emphasis in the preceding verse on setting up the “twelve pillars for the twelve tribes of Israel” and the fact that Moses chose young men to do the work that would later be the job of the priests—thus involving all the tribes instead of only the Levites—my assumption is that the animals for the offerings came from the tribes and therefore would be in multiples of 12.

Burnt offerings are in many places spoken of in the singular. So let’s assume one sheep per tribe, or 12 total. The peace offerings are meant to be a feast, so it’s reasonable to use more animals, especially if everyone in the Exodus is eating. In later days, there was a public Shavuot peace offering using two lambs and two loaves of bread.

Talmud discusses this at length. Beit Shammai and Beit Hillel, two 1st Century schools that were contemporaries and competitors, disagree on the numbers of animals used in sacrifices. Beit Shammai says the the burnt offerings should be twice as valuable as the peace offerings. But Beit Hillel, which is the school modern Jews generally follow, says the opposite:

And Beit Hillel say: The burnt-offering of appearance must be worth one silver ma’a and the Festival peace-offering must be worth two silver coins. The reason for this difference is that the Festival peace-offering existed before the speech of God, i.e., before the giving of the Torah on Mount Sinai, which is not so with regard to the mitzva of appearance. And furthermore, another reason is that we find with regard to the offerings of the princes during the dedication of the Tabernacle that the verse includes more peace-offerings than burnt-offerings. Each prince brought one cow, a ram, and a sheep as burnt-offerings, but two cows, two rams, five goats, and five sheep as peace-offerings.

Chagigah 6a:10, The William Davidson Talmud.

A prince refers to the chief of each tribe. So 12 total. The numbers and kinds of animals refer to the offerings for after the Mishkan was built. The offerings we’re looking at now are after the giving of the Torah (after the very first Shavuot) but only by one day. Not only do we not yet have the Mishkan, but Moses hasn’t even gone up Mt. Sinai to get the instructions for building it. We can only guess at the offerings on this occasion.

Down the rabbit hole (no bunnies were harmed)If you’d really like to go down the rabbit hole of Talmud, consider this section:

Rav Hisda raises a dilemma: This verse, how is it written, i.e., how should it be understood? Should the following verse be read as two separate halves, with the first part consisting of: “And he sent the young men of the children of Israel, and they sacrificed burnt-offerings”, which were sheep; and the second part consisting of the rest of the verse: “And they sacrificed peace-offerings of bulls to the Lord,” i.e., these peace-offerings alone were bulls? Or perhaps both of these were bulls, as the term: “Bulls,” refers both to the burnt-offerings and the peace-offerings.

The Gemara asks: What is the practical difference between the two readings? Mar Zutra said: The practical difference is with regard to the punctuation of the cantillation notes, whether there should be a break in the verse after: “And they sacrificed burnt-offerings,” indicating that these offerings consisted of sheep; or whether it should read: “And they sacrificed burnt-offerings and sacrificed peace-offerings of bulls,” as one clause.

Rav Aḥa, son of Rava, said that the difference between these two readings of the verse is for one who says in the form of a vow: It is incumbent upon me to bring a burnt-offering like the burnt-offering that the Jewish people sacrificed in the desert at Mount Sinai. What is he required to bring? Were they bulls or were they sheep? The Gemara does not provide an answer and states that the question shall stand unresolved.

Chagigah 6b:12-14. The William Davidson Talmud.

The translation I use (Sefaria) is clear that the peace offerings (offerings of well-being) were bulls and doesn’t specify the animal for the burnt offerings. “they offered burnt offerings and sacrificed bulls as offerings of well-being…” But translation can never be as precise as the original, and the original requires context too (context that has been lost over the millennia).

So wait, how many?So we interpret. I say the burnt offerings consisted of 12 sheep (one for each tribe) and 24 bulls (two for each tribe). Am I right? Shrug. It’s as good a guess as I can do.

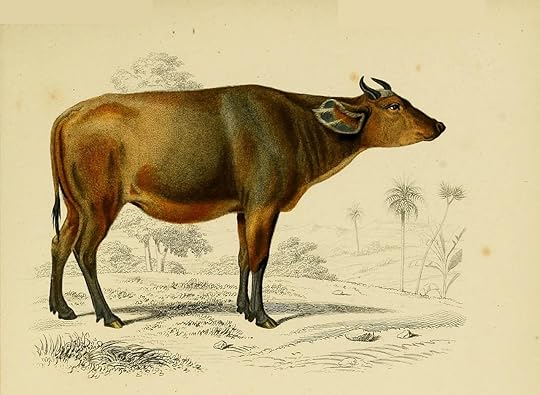

Animal breedsWe don’t know the varieties of livestock the Hebrews might have had, but we can speculate. We can also assume they won’t weigh quite as much as modern livestock because they had to travel long distances and weren’t fattened up in the same ways (not to mention that Exodus livestock didn’t get grain, just sparse grass and manna). Nor were they bred to be bigger and fatter.

The Awassi sheep is a good bet, as they are widely used and indigenous to Southwest Asia and the Levant. The weights depend not only on age (ours are a year or less) and sex (ours are male) but also on if they are improved (no), in rich feeding grounds (no), etc. I’m going to go ahead and assume they’re about 40 kg (88 lbs) each.

A Awassi ram in Kuwait. 2007, Third Eye from Kuwait, Kuwait