Cyndi Norwitz's Blog, page 2

April 15, 2023

A Daily Kitchen Schedule

March 28, 2023

Making Sourdough Bread

March 21, 2023

The Heart of the Kitchen

February 7, 2023

How to Make Things Hot

January 7, 2023

Ancient Metalwork Tidbits

Ancient Egyptian Carpentry

January 3, 2023

Water Everywhere, Except Right Here

I did boatloads (pun intended) of research while writing the first draft of the novel but here and there I handwaved a few things to save for later. Well, it’s later. And, well, it’s wells.

I gave my Hebrew family compound its own well, knowing that the technology and the space issues would probably make that impossible. They’re walking distance to the Nile (one of the Nile Delta distributaries) so do their bathing and laundry there. And those that make bricks are right next to the river and wash up there after their shifts.

But of course they’ll need water back home. Not just for drinking and cooking but also for some washing up, dishes, livestock (those kept within the compound, like birds), and their garden (which is going to mostly be wastewater, but that has to come from somewhere too).

It turns out that there weren’t very many wells. Sometimes the water table was just too deep. Sometimes the ground wasn’t conducive to digging. And other times there simply wasn’t space. We in the modern era may think of a well as just a few feet across with a pump or a bucket lifting the water out. But in areas where it’s hard to dig (or the technology for deep narrow digs didn’t exist) and the water table is low, the mouth of the well can be quite large.

Mouth of the well of Deir el-Medina, looking north (© D. Driaux). “Whilst the water supply system set up seems to have worked efficiently, about one century before the end of the settlement, during the reign of Ramesses III (1187–1157 BC), the administration records on an ostracon the first attempt to dig a well, probably ordered by the state itself, in the vicinity of the workmen’s village. Situated a few hundred metres north of the settlement, in the desert, this large well extended 52 m down to the water level.” Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Mouth of the well of Deir el-Medina, looking north (© D. Driaux). “Whilst the water supply system set up seems to have worked efficiently, about one century before the end of the settlement, during the reign of Ramesses III (1187–1157 BC), the administration records on an ostracon the first attempt to dig a well, probably ordered by the state itself, in the vicinity of the workmen’s village. Situated a few hundred metres north of the settlement, in the desert, this large well extended 52 m down to the water level.” Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).For the New Kingdom workmen’s village outside of the main city of Amarna, a local well wasn’t practical.

The easiest solution was to bring water to the village. Archaeological evidence…show that a water delivery system existed to meet the needs of both the inhabitants of the village and also the animals they tended. Due to the status of the settlement—made by the state, for its own purposes—it makes sense that this isolated village, with few opportunities for self-sufficiency, was supplied by the administration. The origin of the water itself seems to have been one of several wells located at the edge of the main city…The state therefore delegated responsibility to these establishments for sending goods, and the water from their wells to the workmen’s village….The water was carried in a particular kind of vessel: imported and reused Canaanite amphorae or imitations of this form. These handled jars have a slender form, a size (between 50 and 60 cm high) and a capacity (ca. 19 l) which allow a relatively easy transport, in particular on the back of a donkey. The water was then…unloaded and brought a few meters further to a spot in front of the village, named by excavators as the “zîr-area” because of the large number of fragments of water jars (Arabic zîr) found there…The water was then poured into the zîrs which, with their rounded bases, stood in small emplacements built of stone, brick rubble and marl mortar. The water jars provided a standing source of water and villagers then took the water they needed inside the village. Without any written documents, it is quite difficult to estimate the daily needs of the inhabitants; one zîr contained ca. 35 l but this was probably not enough to cover all daily needs, whether for a single man or a family. If that is so, then the jars would have needed to have been refilled more than once. The number of water jars contained in this area is estimated at around 50. This number is also the estimated number of houses, on average, occupied here at any one time. On the basis of one resupply of water stocks per day, almost 1750 l of water had to be sent to the village daily (35 l × 50 zîrs). A simple calculation gives 92 as the number of Canaanite amphorae necessary to bring this important supply of water; and if we consider that one donkey was able to carry two amphorae, one on each side, then 46 donkey journeys were required. Through such calculations we can build a general picture of the logistics of supplying the Amarna workmen’s village with water.

Water supply of ancient Egyptian settlements: the role of the state. Overview of a relatively equitable scheme from the Old to New Kingdom (ca. 2543–1077 BC). Delphine Driaux. Water Hist. 2016; 8: 43–58. Published online 2016 Jan 12. doi: 10.1007/s12685-015-0150-x

It’s unclear how many people, on average, made up one of the 50 households in the above village. In my story, my family compound of around 55 people had 11 huts (nearly 75 people once my time travelers arrived). Let’s round up and say my family needed one-quarter the water of the workmen’s village (because of larger families), though much of that would happen in the Nile itself, without need for transport.

If each amphorae held 11 liters (just under 3 gallons), a human could carry two of them on a yoke. The water for that would weigh 28.5 lbs. I’m not sure how much the weight of the jars (or a similarly sized bucket) and the yoke adds, but it’s not an unreasonable total for a strong man to carry for a mile (the distance of the brickyards in my story, though the Nile itself is closer).

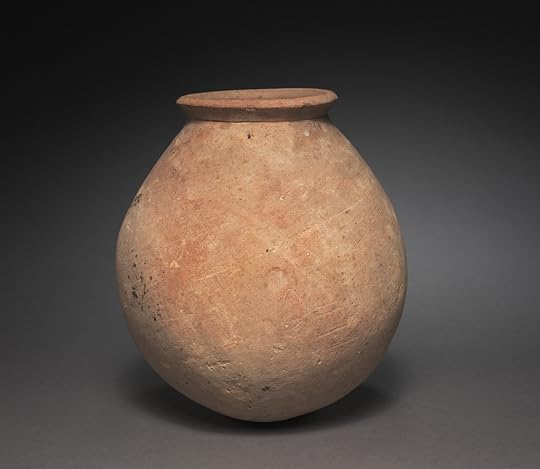

The jug in this picture is more for individual use than for transport and storage (it’s too small!). The Egyptian zîrs are much larger and pointy on the bottom so they need to be stored in a rack or with a base. There is a great picture of them here. And also here.

Water Jar (Globular Jar), 1980-1801 BC, Marl clay. Diameter: 17.9 cm (7 1/16 in.); Overall: 20 cm (7 7/8 in.); Diameter of aperture: 7.6 cm (3 in.), Cleveland Museum of Art, Egyptian and Ancient Near Eastern Art. Egypt, EL-Haraga, cemetery S, tomb 366, excavated in 1914, Middle Kingdom, Second half of Dynasty 12, 1980-1801 BC. Gift of the British School of Archaeology in Egypt.

Water Jar (Globular Jar), 1980-1801 BC, Marl clay. Diameter: 17.9 cm (7 1/16 in.); Overall: 20 cm (7 7/8 in.); Diameter of aperture: 7.6 cm (3 in.), Cleveland Museum of Art, Egyptian and Ancient Near Eastern Art. Egypt, EL-Haraga, cemetery S, tomb 366, excavated in 1914, Middle Kingdom, Second half of Dynasty 12, 1980-1801 BC. Gift of the British School of Archaeology in Egypt.If they instead loaded up a cart (as there were oxen, carts, and well packed pathways), or a hand-pushed cart, they could easily carry a lot more. Let’s say 300 lbs on a smaller cart. Or around 30 gallons (114 liters) of water (after accounting for the weight of the containers).

One of the most important recent milestones has been the recognition in July 2010 by the United Nations General Assembly of the human right to water and sanitation. The Assembly recognized the right of every human being to have access to enough water for personal and domestic uses, meaning between 50 and 100 litres of water per person per day. The water must be safe, acceptable and affordable. The water costs should not exceed 3 per cent of household income. Moreover, the water source has to be within 1,000 metres of the home and collection time should not exceed 30 minutes.

Global Issues: Water. United Nations.

50-100 liters = 13.25-26.5 gallons. This is on the high side for people with access to a river for bathing and laundry and other large projects. It leaves a need for drinking and cooking water (though some would happen at the river) and some hygiene around the home (handwashing mainly).

Another United Nations brief clarifies that water needs:

Include drinking, personal sanitation, washing of clothes, food preparation, and personal and household hygiene…Most of the people categorized as lacking access to clean water use about 5 litres a day-one tenth of the average daily amount used in rich countries to flush toilets….Most people need at least 2 litres of safe water per capita per day for food preparation….The basic requirement of drinking water for a lactating woman engaged in even moderate physical activity is 7.5 litres a day.

The Human Right to Water and Sanitation. Media brief. UN-Water Decade Programme on Advocacy and Communication and Water Supply and Sanitation Collaborative Council.

How much water will need to be hauled from the Nile to the family compound each day? Let’s say 5 gallons (19 liters) per day per person. They can head for the river for extra water trips if necessary, as well as extra trips to do large cooking or washing projects, so it’s not necessary to have a buffer amount.

This gives us 375 gallons per day (for 75 people) or 1420 liters.

If we assume the compound has one wagon (they’ll have more when they leave on the Exodus), we can guess it might carry 400 kg (880 lbs) of cargo. That’s about 110 gallons of water if the containers weigh nothing…let’s say 90 gallons in containers.

Or four trips (Maybe three trips if the brickmakers bring some back with them and there are some trips with a donkey, or a low water needs day, etc.) to the river per day to fill up a cistern (each zîr holding 35 liters or 9.25 gallons, but they would have also used buckets and perhaps some more permanent structure as well).

ReferencesWater supply of ancient Egyptian settlements: the role of the state. Overview of a relatively equitable scheme from the Old to New Kingdom (ca. 2543–1077 BC). Delphine Driaux. Water Hist. 2016; 8: 43–58. Published online 2016 Jan 12. doi: 10.1007/s12685-015-0150-xThe Samana well/Egypt. Artefacts — Scientific Illustration & Archaeological Reconstruction. Client: Henning Franzmeier, M.A., Independent researcher/Egyptologist, Germany. Status: Completed in 2008.Global Issues: Water. United Nations.The Human Right to Water and Sanitation. Media brief. UN-Water Decade Programme on Advocacy and Communication and Water Supply and Sanitation Collaborative Council. Zir Vessels from the Tomb of Osiris at Umm el-Qaab. Julia Budka. Originalveröffentlichung in: Bulletin de liaison de la céramique égyptienne 24, 2014, S. 121–130.January 2, 2023

Sewing & Other Fabric Arts

Despite their clothing being rather straightforward (mostly lengths of undyed linen tied in various ways or sewn into simple shapes), Egyptians in ancient times had pretty sophisticated resources for the fabric arts.

Needles Ancient Egypt Medical tools. From top to bottom, a copper needle, a silver needle (missing the eye), and a copper pin with loop head. All are dated to the Predynastic period, and were found in Naqada. Nunn, J. 1996. Ancient Egyptian Medicine. Norman:University of Oklahoma Press. Page 172.

Ancient Egypt Medical tools. From top to bottom, a copper needle, a silver needle (missing the eye), and a copper pin with loop head. All are dated to the Predynastic period, and were found in Naqada. Nunn, J. 1996. Ancient Egyptian Medicine. Norman:University of Oklahoma Press. Page 172.The needles in the above picture don’t state their lengths (and, oddly, claim them as medical tools, not fabric ones). They come from long before New Kingdom days (6000-3150 BCE) yet show quite complex metalwork with two different kinds of metal. That top needle in particular would look completely ordinary in any modern sewing basket.

In other photos from the New Kingdom and before, we see needles made out of bone, ivory, and bronze or copper alloy and ranging in length from 8 cm (3 1/8 in) to 20 cm (8 1/8 in), the longer ones noted as being for weaving fish nets and other textiles.

NeedleworkAncient Egyptians embroidered clothing and other fabrics and used a range of different stitches for that and other sewing and needlework.

The ancient Egyptians used a comparatively narrow range of decorative embroidery stitches. Identified to date, these are the blanket stitch, chain stitch, running stitch, satin stitch, seed stitch, stem stitch and the twisted chain stitch

In addition, darning and mending of worn textiles were sometimes carried out using coral stitches and overcast stitches, as well as couching, but these should be regarded as functional, rather than decorative forms.

Ancient Egyptian Stitches, Stichting Textile Research Centre (TRC).

While this artifact isn’t quite from the right place or old enough for our purposes, it was the best I could find that was public domain or with a Creative Commons license. For a terrific picture of a contemporaneous embroidered work, see Tutankhamun and Decorative Needlework.

[image error]Detail of the embroidered dress of an Apkallu. From Nimrud, Iraq. 883-859 BCE. Ancient Orient Museum, Istanbul. A zoomed-in image of the embroidered dress of a standing male Apkallu, depicting a pair of 4-legged winged animals in addition to the motif of the sacred tree (palm tree). From the North-West Palace at Nimrud (ancient Kalhu), Northern Mesopotamia, Iraq. Neo-Assyrian Period, reign of Ashurnasirpal II, 883-859 BCE. Ancient Orient Museum, Istanbul.Functional Woven ItemsMats

An expert on needlework, Catherine Leslie [author of Needlework Through History: An Encyclopedia (Handicrafts Through World History Series), 2007] reveals that needles with eyes and beads made from stone were used by prehistoric people in 38,000 B.C.E. That was 30,000 years ago, before the existence of written language and therefore there is no written record of this. It is, however, thought that the earliest artworks were likely part of religious rituals.

The oldest surviving pieces of embroidered material date from approximately 2,000 B.C.E. and were found in Egyptian tombs. These artefacts include hem panels found on the tunic of the famous Egyptian pharaoh, Tutankhamun.

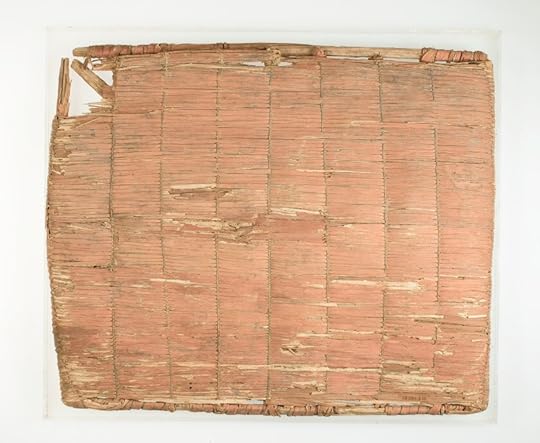

Woven from various fibers, including jute.

Mat. Date: ca 1550–1295B. C, New Kingdom, Dynasty 18. From Upper Egypt, Thebes, Egypt, fiber. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Look and Learn. Public Domain Dedication (CC0 1.0)

Mat. Date: ca 1550–1295B. C, New Kingdom, Dynasty 18. From Upper Egypt, Thebes, Egypt, fiber. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Look and Learn. Public Domain Dedication (CC0 1.0) Mat. Date: ca 1550–1295B. C, New Kingdom, Dynasty 18. From Upper Egypt, Thebes, Egypt, fiber. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Look and Learn. Public Domain Dedication (CC0 1.0)Rope

Mat. Date: ca 1550–1295B. C, New Kingdom, Dynasty 18. From Upper Egypt, Thebes, Egypt, fiber. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Look and Learn. Public Domain Dedication (CC0 1.0)Rope These look like they came off a modern dock. Made from palm fibers or reed.

Rope. Date: ca 1550–1295B. C, New Kingdom, Dynasty 18. From Upper Egypt, Thebes, Egypt, palm fiber? The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Look and Learn. Public Domain Dedication (CC0 1.0)

Rope. Date: ca 1550–1295B. C, New Kingdom, Dynasty 18. From Upper Egypt, Thebes, Egypt, palm fiber? The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Look and Learn. Public Domain Dedication (CC0 1.0) Rope Jar Sling. Date: ca 2030–1640B. C, Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 12. From Upper Egypt, Thebes, Egypt. Reed rope. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Look and Learn. Public Domain Dedication (CC0 1.0)Fish nets

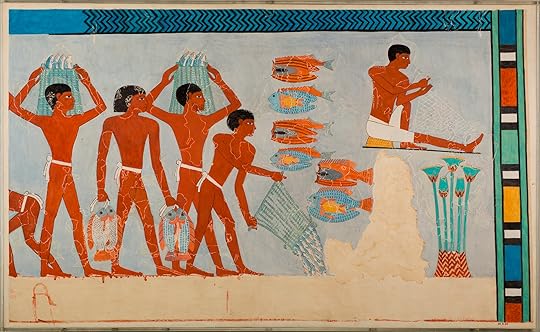

Rope Jar Sling. Date: ca 2030–1640B. C, Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 12. From Upper Egypt, Thebes, Egypt. Reed rope. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Look and Learn. Public Domain Dedication (CC0 1.0)Fish nets Facsimile: Scene of Fish Preparation and Net Making. Date: 1926 AD; original ca 1479–1458B. C, Twentieth Century; original New Kingdom, Original New Kingdom, Dynasty 18, Joint reign of Hatshepsut and Thutmose III. Original from Upper Egypt, Thebes, Egypt.

Facsimile: Scene of Fish Preparation and Net Making. Date: 1926 AD; original ca 1479–1458B. C, Twentieth Century; original New Kingdom, Original New Kingdom, Dynasty 18, Joint reign of Hatshepsut and Thutmose III. Original from Upper Egypt, Thebes, Egypt.Creator Norman de Garis Davies nina or artist (1865–1941). Tempera on paper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Look and Learn. Public Domain Dedication (CC0 1.0)ReferencesAncient Egyptian Stitches, Stichting Textile Research Centre (TRC).Tutankhamun and Decorative Needlework (Egypt), Stichting Textile Research Centre (TRC).Embroidery: History and How It’s Made, F&P Interiors.

December 31, 2022

Soap & Cleaning Materials of Ancient Egypt

Now soap is something I know well, being a soapmaker when I’m not a writer. But using a digital scale to precisely measure pure sodium hydroxide crystals and water to mix with an exact weight of olive oil is not exactly an ancient practice, though the basic idea of a caustic base plus fat is timeless.

Star shaped Castile soap from Tikvah Organics.

Star shaped Castile soap from Tikvah Organics.But what exactly did the Ancient Egyptians use in the time period of the New Kingdom to wash their bodies, their hair, their clothes, their dishes, and so on?

SoapLegend has it that the first soap was accidentally produced on Mt. Sopa, a site of animal sacrifice. As the goat meat burned, fat dripped down through the fire, bonding to lye leaching out of the ashes. The combination flowed down the mountainside and collected in the clay of the riverbanks, where women used the clay to scrub laundry clean. Although soap was known in the Fertile Crescent as early as 2000 BCE, it was used in the treatment of wounds and in hairdressing before its cleansing properties were understood. In the Mediterranean, soap was entirely unknown: Egyptians and Romans used oils for bathing and the Egyptians used natron, a crystallized rock of brine, to launder clothes. Although some individual Viking and Celtic tribes discovered soap independently, it was not widely known in Europe until the Arab invasion of the Byzantine Empire. It took considerably longer for the invention to reach northern Europe; the Celts are credited with introducing soap to Britain in 1000 CE. Although the Arabs used animal fat for their soaps, the abundance of olive trees in the Mediterranean area led to the development of soaps based on olive oil and lye from the ashes of the barilla, a common plant.

Castile Olive Oil Soap, Spain, 2000 BCE. Smith College History of Science: Museum of Ancient Inventions.

The Ebers Papyrus (c. 1550 BCE, late Second Intermediate Period or early New Kingdom), mentions soap along with other Egyptian medical information. It was made by mixing (some sites saying boiling) animal and vegetable oils with alkaline salts and used both for washing and treating skin diseases. All the sources I found (mostly soapmakers) say pretty much the same thing, but none are primary or even secondary sources. They just parrot the same information. But it’s pretty consistent.

What I’m not finding out is which ingredients they used to produce soap and what the soap was like. Some sources say it was harsh, but I don’t know if that’s based on documents or a recipe or if it’s just a guess, since more modern soaps before the standardization of lye were often caustic.

Other sources say the Ancient Egyptians used olive oil to make soap. Olive oil was certainly in production nearby during the New Kingdom (and long before) and we know that Egyptians used it. It’s unclear if it was actually used to make soap with or how expensive it was. Would it have been available to workers? Some people did use olive or other oils to clean themselves when they did not have soap.

Natron Natron deposits, Trou au Natron, Tibesti, Chad. 10 November 2017. Alexios Niarchos

Natron deposits, Trou au Natron, Tibesti, Chad. 10 November 2017. Alexios NiarchosNatron is a naturally-occurring compound of sodium carbonate and sodium bicarbonate. At the present time it is found in three localities in Egypt, two (the Wadi Natrun and the Behera province) in Lower Egypt and one (El-Kab) in Upper Egypt…The natron in the Wadi Natrun occurs dissolved in the lake water—from which a thick layer has gradually been deposited at the bottom of some of the lakes—and also as an incrustation on the ground adjoining many of the lakes. The amount present is very considerable, although the wadi has been the source, not only of the principal Egyptian supply, but also of a small export trade, for several thousands of years….

In ancient Egypt natron was used in purification ceremonies, especially for purifying the mouth; for making incense; for the manufacture of glass, glaze, and possibly the blue and green frits used as pigments, which may be made either with or without alkali, but which are more easily made if alkali is present; for cooking; in medicine and in mummification.

The Occurrence of Natron in Ancient Egypt, A. Lucas, The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 18, No. 1/2 (May, 1932), pp. 62-66 (5 pages), Sage Publications, Inc.

Natron is commonly used for washing clothes or can be mixed with oil to make a form of soap, though it’s not a particularly strong base.

LaundryLaundry would have been washed in the Nile River. Along with bathing and more.

Laundry day: washing clothes while the children swim in the (mostly dry) river.

Laundry day: washing clothes while the children swim in the (mostly dry) river.Madurai, Tamil Nadu, India. 11 December 1999. Ryan from Toronto, Canada.Washing Up

Bathing, food preparation, dishwashing, etc. All in the available water source.

Women at a Village Pond in Matlab, Bangladesh, Washing Utensils and Vegetables. The woman on the right is putting a sari filter onto a water-collecting pot (or kalash) to filter water for drinking. November 17, 2003. Bradbury J: Beyond the Fire-Hazard Mentality of Medicine: The Ecology of Infectious Diseases. PLoS Biol 1/2/2003: e22. Anwar Huq, University of Maryland Biotechnology Institute, Baltimore, Maryland, United States.ReferencesCastile Olive Oil Soap, Spain, 2000 BCE. Smith College History of Science: Museum of Ancient Inventions.Ebers Papyrus. Wikipedia.Olive Oil History: Ancient Egypt, Hazienda La Rambla.The Occurrence of Natron in Ancient Egypt, A. Lucas, The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 18, No. 1/2 (May, 1932), pp. 62-66 (5 pages), Sage Publications, Inc.Natron. Wikipedia.

Women at a Village Pond in Matlab, Bangladesh, Washing Utensils and Vegetables. The woman on the right is putting a sari filter onto a water-collecting pot (or kalash) to filter water for drinking. November 17, 2003. Bradbury J: Beyond the Fire-Hazard Mentality of Medicine: The Ecology of Infectious Diseases. PLoS Biol 1/2/2003: e22. Anwar Huq, University of Maryland Biotechnology Institute, Baltimore, Maryland, United States.ReferencesCastile Olive Oil Soap, Spain, 2000 BCE. Smith College History of Science: Museum of Ancient Inventions.Ebers Papyrus. Wikipedia.Olive Oil History: Ancient Egypt, Hazienda La Rambla.The Occurrence of Natron in Ancient Egypt, A. Lucas, The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 18, No. 1/2 (May, 1932), pp. 62-66 (5 pages), Sage Publications, Inc.Natron. Wikipedia.

The Lights of the Exodus

So what sort of lighting did folks use in Egypt during the New Kingdom? Oddly, most sources say there are few surviving lamps, though many point out this is because lamps then would be ordinary objects and not specialty ones like we have in modern times. But there certainly were lamps. And also torches.

LampsRobins, writing in 1939, concludes that Ancient Egyptian lamps would have had floating wicks and be made of stone or possibly pottery (glass being not an option in that time period). He claims these lamps can be hung, set into a wall recess, placed on a surface, or held, but he doesn’t show how they might be hung.

Broadly speaking, the prototypes of nearly all manufactured lamps are sea-shells and hollowed stones…there is absolutely no evidence of the shell being the origin of such lamps as the ancient Egyptians had during most of their history. The hollowed stone seems a much more likely source…[but] there is no clear evidence that any of the many stone objects found in Egypt were lamps.

There is, nevertheless, a fair amount of evidence that early lamps in Egypt owed nothing to the shell and were of bowl or saucer form…the only likely alternative is that it grew out of the use of ordinary pottery (or stone) household vessels as lamps by providing them with oil and a wick.

Herodotus [writing in 5th century BCE] states that “At Sais…they use lamps in the shape of flat saucers filled with a mixture of oil and salt, on the top of which the wick floats.”…If the lamps of ancient Egypt were of the floating-wick type, without any form of spout, this would account for the difficulty of recognizing them…since the flame floated more or less in the centre of an open bowl there are not necessarily any visible signs of burning.

The Lamps of Ancient Egypt, F. W. Robins, The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 25, No. 2 (Dec., 1939), pp. 184-187 (4 pages), Sage Publications, Inc.

Smith discusses at length lamps found in Palestine in the early Iron Age, just after the Exodus, if we wish to follow tradition and say that the Hebrews did migrate from Egypt to Palestine around 1311 BCE.

From the time of the Hebrew settlement through the beginning of the divided monarchy, the period commonly called Iron I, which spanned approximately the years 1200-900 B.C…the only lamp in widespread use in Palestine was a simple wheelmade one [article photo is the same as the photo below]. Archaeologists, seeking a convenient descriptive term, have variously called this a “shell lamp,” “cocked hat lamp,” and “saucer lamp.” The ancient Hebrew…called it by the generic name ner (plural neroth), a word meaning simply “lamp.” [A term also used earlier for celestial bodies.]…

The Hebrews did not invent the saucer lamp, but borrowed it largely unchanged from the Canaanites of the end of the Late Bronze Age, whose ancestors in Syria and Palestine had gradually been developing it since early in the 2nd millennium B.C. Contrary to widespread assumption, the lamp did not arise as an imitation of a shell. Bivalve shells may indeed have been used as lamps in some instances along the Mediterranean coast, as they apparently were upon occasion at Carthage in North Africa, and couch shells were made into lamps (and copied in stone and metal as well) in Mesopotamia as far back as the 3rd millennium B.C., but these practices do not stand in the mainstream of lamp history. The saucer lamp actually developed from the ordinary household bowl, which itself had been used as a lamp during the Early Bronze Age…The development of the saucer lamp through the Middle and Late Bronze Ages consisted mainly of the evolution of the spout into an increasingly large and well-defined feature of the lamp…By virtue of this Canaanite ancestry, Hebrew lamps had cousins in Cyprus, north Africa, Egypt, Malta, Sardinia and elsewhere.

The Household Lamps of Palestine in Old Testament Times, Robert Houston Smith, The Biblical Archaeologist, Vol. 27, No. 1 (Feb., 1964), pp. 1-31 (31 pages), The University of Chicago Press.

Saucer Lamp, Ceramic, Wheelmade, Hard sandy ware saucer lamp, mottled brown and light-red surface, smoother, with smoked spout. Cultural Period: Iron IIA – Iron IIC, Early Date (BCE): 900, Late Date (BCE): 600. Length (cm): 12.7, Width (cm): 13.0, Height (cm): 3.8, Weight (g): 149.5. Holbrook Hall, Pacific School of Religion, Tell en-Nasbeh Collection.

Size & StyleWicks & OilSpecimens [from Iron I] were usually from five to six inches in length, though potters sometimes turned larger ones…the kind of clay which was used varied with the locality, but throughout the Iron I period it tended everywhere in Palestine to be coarse with a sprinkling of limestone grits to give it strength…An Iron I lamp was usually fired moderately hard to some drab shade of brown…it was almost never painted or otherwise decorated.

The Household Lamps of Palestine in Old Testament Times, Robert Houston Smith, The Biblical Archaeologist, Vol. 27, No. 1 (Feb., 1964), pp. 1-31 (31 pages), The University of Chicago Press.

Equipment & PlacementWicks were ordinarily made of flax…a wick could presumably be plaited from raw flax with little difficulty, but one could also be improvised from worn-out linen cloth or a number of other substances…the wick was usually allowed to project slightly beyond the edge of the spout. The amount of this projection, along with the size and porosity of the wick, largely determined the size of the flame. The ordinary saucer lamp was intended to hold only one wick, as its single spout indicates. When a householder wanted an especially bright light he could sprinkle some salt into the oil, apparently with the idea that it would clarify the flame. The Greek historian Herodotus noted in the 5th century B.C. that Egyptians fed their lamps on a mixture of oil and salt, and in the early centuries of the Christian era rabbis also knew the practice…G. and C. Charles-Picard, who have performed some experiments with ancient lamps, say that a lamp’s flame is brightened by the addition of a few grains of coarse salt directly to the wick, but in my own experiments with ancient lamps I have been unable to get any satisfactory results by this method….

Many substances could be and were used as fuel for lamps, but the commonest of them was olive oil…[using the] oil of lower quality…Imported oils — sesame oil from Mesopotamia, castor oil from Egypt, or even more exotic substances — may occasionally have been used as lamp fuel…A lamp of moderate size held enough oil for it to burn throughout the night.

The Household Lamps of Palestine in Old Testament Times, Robert Houston Smith, The Biblical Archaeologist, Vol. 27, No. 1 (Feb., 1964), pp. 1-31 (31 pages), The University of Chicago Press.

Outdoor UseObviously a householder needed a storage container for the oil supply, but we cannot identify any particular form or size of vessel used for this purpose. He also needed a sharp-pointed instrument with which to adjust the position of the wick from time to time as the lamp burned. Numerous metal and bone objects which might have served such a function have been found in Palestine, but apparently none in clear association with lamps…which suggests that the householder frequently used nothing more than a sliver of wood as a wick-adjuster. Tweezers sometimes may have been used to extinguish a lamp’s flame…Probably not to be included among the items of lamp maintenance is the knife-blade, since lamp wicks did not have to be kept trimmed in order to operate satisfactorily.

Lamps were probably kept most of the time in concave niches in the walls of the house…When the householder put a lamp on a table he probably placed beneath it a bowl, primarily for the purpose of guaranteeing stability to the round-bottomed vessel. Rabbinic literature of many centuries later speaks of this custom, but Iron Age evidence is largely lacking…Iron I lamps are often poorly balanced, tending to tip backward when placed on a flat surface. The lamps cannot have been used in such a position; the lamp-maker seems to have supposed that the lamp would be placed in some kind of concave resting place…on a table, a bowl would most easily meet this need. A bowl beneath the lamp would also have caught any oil which might slowly seep through the lamp, though a well-made specimen did not absorb and exude oil very rapidly. Some scholars have suggested that a lamp was soaked in water prior to each use, or even kept in a saucer filled with water, so that the water would fill the pores of the clay and prevent oil seepage. It is somewhat more likely that users poured a little water into a lamp before they poured in the oil; this would fill the pores of the clay and give the oil a surface upon which to float. [Lamp stands seem to only come later and even the Iron I versions were mostly used in religious spaces.]

The Household Lamps of Palestine in Old Testament Times, Robert Houston Smith, The Biblical Archaeologist, Vol. 27, No. 1 (Feb., 1964), pp. 1-31 (31 pages), The University of Chicago Press.

LanternsDesigned as they were for household use, saucer lamps were probably seldom used for nighttime travel, for although their size made them portable their open oil reservoirs permitted the oil to spill easily, and their small, un-protected flames must have been fairly ineffective in open spaces…Lantern-shaped terracotta housing, into which a lamp could be inserted and carried with its nozzle projecting from an opening, was probably known but was not widely used; no Iron Age specimens have yet appeared in Palestine….

The only really effective light for extended travel at night, especially over rugged and unfamiliar ground, would have been that provided by the torch (Hebrew lappid), presumably devised of wood…probably many people did not bother with artificial illumination at all when traveling by night.

The Household Lamps of Palestine in Old Testament Times, Robert Houston Smith, The Biblical Archaeologist, Vol. 27, No. 1 (Feb., 1964), pp. 1-31 (31 pages), The University of Chicago Press.

While the idea of a lantern is simple—just a way to carry a lamp or a candle for outdoor use—they didn’t seem to be used in the Western world until at least the Common Era, much later than the dates we’re looking at. The earliest lanterns in the world may be candle frames and paper lanterns from the Han Dynasty of China, but even these aren’t around before around 104 BCE.

CandlesWhile technically anything with a wick is a candle, I’m excluding from this section anything that instead counts as a lamp. Candles have a distinct advantage over lamps. Lamps use a liquid flammable material for the wicks and candles use a solid one (which might drip but generally doesn’t spill). Most people do define candles as having solid fuel, but a lot of the historical sources out there (even the more academic ones but especially the ones that aren’t) will mix up wicked lamps with candles.

Candles were first mentioned in Biblical times, as early as the tenth century BCE. These early candles were made of wicks stuck into containers filled with a flammable material. The first dipped candles were made by the Romans from rendered animal fat called tallow…In the 1500’s, beeswax was introduced as an alternative to tallow…All candles were made by dipping until the 1400’s, when a French inventor introduced molds for taper candles….Wicking can be made from almost any kind of fiber; one of the most common in early days was loosely spun cotton.

Candles, 1000 BCE (Candles, Roman, 500 BCE). Smith College History of Science: Museum of Ancient Inventions.

If we’re looking at a wax or tallow candle, something reasonably solid to set your wick in, the earliest example appears to be around 500 BCE, though the Smith College source also implies 1000 BCE. But many other sources put the Roman use of dipped tallow candles at 100 BCE or a tad earlier. Either way, this is too late for our purposes.

TorchesIn ancient Egypt, torches were widely used, both for daily life uses and also for different rituals…Webster’s Dictionary, which agrees with the Oxford Dictionary, defines “torch” as “A light or luminary formed of some combustible substance, as resinous wood, twisted tow soaked in tallow, generally carried in the hand.” Torches or tapers are known from the representations on the walls of New Kingdom tombs and temples, the commonest type was made of a strip of linen folded double at half its length and twisted…then soaked in fat, such a torch could be held in the hand or mounted on ritual holders which sometimes took the form of Nile god or n emblems. In the second half of Dynasty 18 (Thotmosis IV onward ), this form was supplemented by a sort of cresset, a large rhomboidal lump of fat moulded around the top of a stick, with the lower end of the stick serving as a handle, the lump of fat acquired a flat-based conical shape before the end of the dynasty, retained that form throughout the Ramesside period…

The Torches in Graeco-Roman Egypt: The Ritual and Practical uses, Dr. Manal Mahmoud Abdel Hamid (Lecturer in the Faculty of Tourism and Hotels, Guidance Dep., Alexandria University).

So, yes, torches. In the New Kingdom. Other sources put the origin of torches much earlier than that.

RushlightsA cheaper and less sophisticated type of torch. In Victorian English, rushlights were a common way for poorer people to light their homes. They were cheap and fairly easy to make but also messy and dripped grease. One length would burn for 30-60 minutes. They required a holder, so the rush could burn while pointed downward at 45°.

In the summer, when the common rushes of marshy ground were at their full growth, they were collected by women and children. The rush is of very simple structure, white pith inside and a skin of tough green peel. The rushes were peeled, all but a narrow strip, which was left to strengthen the pith, and were hung up in bunches to dry. Fat of any kind was collected, though fat from salted meat was avoided if possible. It was melted in boat-shaped grease-pans that stood on their three short legs in the hot ashes in front of the fire. They were of cast-iron; made on purpose. The bunches, each of about a dozen peeled rushes, were drawn through the grease and then put aside to dry.

Rushlight: How the Country Poor Lit Their Homes (1904), Gertrude Jekyll. The Victorian Web.

The Atlantic puts Egyptian invention of rushlights at 3000 BCE, other sources say 5000-3000 BCE. Either way, they existed in our desired time and place. As did copious amounts of animal fat.

Rushlight in a holder.References

The Lamps of Ancient Egypt

, F. W. Robins, The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 25, No. 2 (Dec., 1939), pp. 184-187 (4 pages), Sage Publications, Inc.The Household Lamps of Palestine in Old Testament Times, Robert Houston Smith, The Biblical Archaeologist, Vol. 27, No. 1 (Feb., 1964), pp. 1-31 (31 pages), The University of Chicago Press.Lantern. Wikipedia.Lantern Festival. Wikipedia.Observations of an intern: African American Invention Highlight. Castle Museum of Saginaw County History. Feb 22, 2021.Chinese Lanterns: Their History and Modern Uses, the CLI Team. February 15, 2022.Candles, 1000 BCE (Candles, Roman, 500 BCE). Smith College History of Science: Museum of Ancient Inventions.History of candle making. Wikipedia.Candle. Wikipedia.The Torches in Graeco-Roman Egypt: The Ritual and Practical uses, Dr. Manal Mahmoud Abdel Hamid (Lecturer in the Faculty of Tourism and Hotels, Guidance Dep., Alexandria University).Rushlight. Wikipedia.Rushlight: How the Country Poor Lit Their Homes (1904), Gertrude Jekyll. The Victorian Web.The Iridescent History of Light, May 17, 2018, Video by The Atlantic.

Rushlight in a holder.References

The Lamps of Ancient Egypt

, F. W. Robins, The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 25, No. 2 (Dec., 1939), pp. 184-187 (4 pages), Sage Publications, Inc.The Household Lamps of Palestine in Old Testament Times, Robert Houston Smith, The Biblical Archaeologist, Vol. 27, No. 1 (Feb., 1964), pp. 1-31 (31 pages), The University of Chicago Press.Lantern. Wikipedia.Lantern Festival. Wikipedia.Observations of an intern: African American Invention Highlight. Castle Museum of Saginaw County History. Feb 22, 2021.Chinese Lanterns: Their History and Modern Uses, the CLI Team. February 15, 2022.Candles, 1000 BCE (Candles, Roman, 500 BCE). Smith College History of Science: Museum of Ancient Inventions.History of candle making. Wikipedia.Candle. Wikipedia.The Torches in Graeco-Roman Egypt: The Ritual and Practical uses, Dr. Manal Mahmoud Abdel Hamid (Lecturer in the Faculty of Tourism and Hotels, Guidance Dep., Alexandria University).Rushlight. Wikipedia.Rushlight: How the Country Poor Lit Their Homes (1904), Gertrude Jekyll. The Victorian Web.The Iridescent History of Light, May 17, 2018, Video by The Atlantic.