Catherine Grove's Blog, page 2

March 13, 2023

When Irish was heard in the Ottawa Valley

Joseph Bouchette(1) , Surveyor General of Lower Canada, reached Rawdon county’s uncharted northern reaches, on August 24, 1824. To his amazement, he found a thriving community of 200 Irish-speaking Catholic squatters(2) .

Bouchette was no stranger to the Irish. The British colony of Newfoundland had over 200 fishing settlements (total population of 19,000 in 1815) of Irish-speaking Catholics, who composed half of the colony by the late 1700’s(3). ‘Thalamh an Eise ‘, as they’d called their adopted land, translated to Land of Fish.

And in New France, they’d served in the French colonial military, before the British capture of Quebec, in 1759. As early as the 1600’s there were at least 100 Irish-born families and 30 mixed Irish-French Canadian families living in the French colony, as refugees of British rule(14).

During the late 1700’s, Mrs. Mary Griffen, Irish wife of a soap maker, illegally purchased and developed coveted industrial land, of western Montreal. After a prolonged court case, this disputed land was returned to the original owner in 1814. Irish labourer tenants remained as did her name, ‘Griffentown’, upon this urban Irish community.

Joseph Bouchette identified Rawdon’s Laurentian foothills as “waste land of the crown” on his map of 1815.(1-a) Yet brave Irish had crossed Atlantic’s perilous ocean and cleared a clearing in this remote densely forested land and farmed the thin top soil. Canada’s act of compromise with French Canadians gave them peculiar protection.

Figure 1: Location of Irish Settlements circled in green) established after Joseph Bourchette’s survey of 1815 (north of Montreal)

For centuries British rule imposed cruel Penal Laws on the Irish in attempt to coerce Roman Catholics to embrace of the Protestant Church of Ireland. Successive penalizations cumulated in Irish Roman Catholics subjected to heavy fines and imprisonment for participating in Catholic worship, death to practicing priests, increased taxation to upkeep the Protestant church, and barred them from voting, holding public office, owning land, teaching and speaking their native tongue. They were not even permitted to play Irish music(4).

By the late 1700’s, under the anti-Catholic King George III, Irish Catholics could not hold office, own an expensive horse, possess weaponry, study law or medicine, hold civil or military office or inherit property, for their land could be readily dispossessed to a nearest Protestant relative. Although some property rights were restored under the Roman Catholic Relief Act (1774), nothing was assured. Severe impoverishment and collapse of the living standard of Irish people resulted. These laws were viewed as eternal damnation of the Irish, for Roman Catholicism interpreted denial of church sacraments as dooming believers to spiritual purgatory.

In Lower Canada, adoption of the politically motivated Quebec Act of 1774, assured freedom of Roman Catholic faith to the larger French Canadian population along with reinstatement of their French civil law (in combination with British criminal law), and protection of language, as well as the existing system of hereditary nobility (seignory system of New France). This legislation purposed to avert an American French Revolution. For the Irish, the Quebec Act provided refuge in Canada.

Figure 2: Arrival of Irish refugees to Lower Canada in early 1800’s

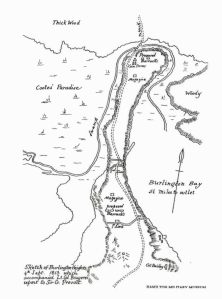

Joseph Bouchette’s 1831 survey of Lower Canada(1) identified at least 4 Irish speaking settlements in the Laurentians (Rawdon, Kildare, Kilkenny and Deux Montagnes. See Figure 1). Not all were squatters and not all came directly from Ireland.

From Montreal, Father Patrick Phelan convinced the Sulpician Deux-Montagnes mission to donate land and relocated with several impoverished Irish families to the present-day area of St.Columban in Argenteuil County on the eastern edge of the Ottawa Valley (see Figure 3).

Religious-based schools of these communities, was in both French and English, indicating non-British alignment in their adopted homeland. Freedom of Irish usage was enjoyed, yet religious freedom was of greater priority. Only the community of Kilkenny was Protestant(5).

Figure 3: Irish Settlement, North of Deux Montagnes, Eastern Ottawa Valley (Bouchette’s 1931 survey)

Further to the west, within the basin of the Ottawa Valley, Irish speaking communities settled in the southern Laurentian reaches of Mayo (Papineau county) and Low (north of Gracefield, along the Gatineau tributary of the Ottawa). Farming was difficult, soil thin, yet by supplementing with seasonal lumber work, these communities survived. Originating from rural Ireland, they were familiar with hardship. Of the famine to hit Ireland within a generation, it was reported that a single acre of potatoes could feed a family for a year(6).

Figure 4: Canadian clearing in early 1800’s

The Irish-speaking Catholic village of Mayo, on the Quebec side of the eastern Ottawa valley was populated by pre-famine immigrants (1820-30) who maintained strong connection to their Irish roots. A replica of the Our Lady of Knock Shrine, in Ireland’s county Mayo, was constructed in the late 1880’s as a local pilgrimage site (7)..

To the west, north of present-day Ottawa, along the Gatineau River, lies the township of Low. During the Great Famine (1845-52) founder Charles Adamson Low, a Gatineau lumber baron, populated this area with Catholic Irish settlers(8). Although the true number of Irish speakers is unknown, a 1901 Census of this region reported many instances of Irish as a mother-tongue. Sadly, many children were listed as English speakers, indicating declining use of Irish language.

Saint Patrick’s Mount, north of Lake Calabogie, was also populated by Irish squatters when land surveyors arrived in the 1850’s. These Gaelic speakers had been there since the early 1800’s when seventeen families, joined their shantymen heads-of-family. Other Irish soon settled nearby, with missionary Catholic priests serving this region until a pioneer priest arrived from Ireland in 1842. Saint Patrick Mount’s Catholic devotion is exemplified by a Holy Well, near Constant Creek, blessed in the Irish Tradition, as well as a beautiful old church, and cemetery.

Figure 5: Holy Well of Saint Patrick’s Mount

Over the centuries, this community has been known for producing many priests and nuns(9.). Although located in Upper Canada, this reflects an openness to respect of Catholic rights and Irish language and culture in the early 1800’s.

Prior to 1793, under Irish Penal Laws, Irish Catholics could hold neither military commission nor possess weaponry. Despite this, the British military actively recruited among the Irish between the years 1750 and 1820. Likely the high attrition of forces during the American Revolution and Napoleonic Wars played a role. By 1780 Irish formed a third of rank, of which three quarters identified as Roman Catholic. Passing of the Irish/British Interchange Act of 1811 allowed military Roman Catholics freedom of choice in worship; religious pluralism was provided to military and accompanying family by the British(10) in Canadian military settlements established post-War of 1812, and included Anglican, Presbyterian and Roman Catholic churches. Though freedom was enjoyed, Upper Canada’s Anglophile ruling class remained closed to Roman Catholics, and Irish.

In 1820 George Ramsey, 9th Earl of Dalhousie was promoted to Governor General of British North America. His previous position, as Lieutenant-Governor of Nova Scotia, drew him to the plights of black refugees and indigenous people. Willing to provide rations and land to those who showed ‘shrewd disposition’, he supported humanitarian endeavors of Catholic priests and held enthusiasm for social improvement.

After the War of 1812, Britain wanted to quickly populate Upper Canada to stave off American Republic expansion from the south.

Recognizing Ireland’s unrest and poverty, Ramsey proposed alleviating both the ‘Republican’ and ‘Irish’ problems by offering landownership and participation in local government. To this end, he dispatched Peter Robinson ( a member of Upper Canada’s legislature, and brother of Sir John Beverly Robinson, Upper Canada’s Attorney General), to Ireland to convince impoverished Irish to immigrate to Canada. A promise of assisted passage and 70 acres was extended to all willing eligible males between ages 18 to 45 of County Cork. This region was chosen due to a local severe economic downturn that affected all, regardless of faith(11).

Few responded, at first, for the scheme was viewed as little different from penal transportation to Australia. Resistance was also met by local landowners who resented that he would draw away cheap labour and the most ambitious of workers.

Persisting with a promise of land and supplies, as well as religious and civil freedom, Robinson managed to convince approximately 500 settlers to relocate. Traveling across the Atlantic in two ships, they debarked at Quebec City, continuing on to Montreal by steamboat. From there, they traveled to Prescott on barges and flat-bottomed boats, then made their way north by foot, with their few possessions pulled by oxcart This first group settled in the Bathurst District of Upper Canada (eastern Ontario), including present-day townships of Ramsey, Goulburn, Huntley and Pakenham. Log homes were completed by November 1, 1823.

Figure 6 : Peter Robinson Settlement (shaded in green) of Bathurst District of Upper Canada, 1823. Red dots mark Military Settlement Towns of Lanark, Perth and Richmond.

Spring of 1824 found some land to be too rocky or swampy for farming. Where land was unsuitable, alternative land was supplied. Many stayed on their clearing and farmed; some found work lumbering or on the Rideau Canal construction in 1826(12).

Figure 7 : Irish speaking regions circled in green.

Irish-speaking Roman Catholics populated Ottawa Valley’s backwoods. Land was cleared and churches built. Within a generation English replaced Irish in these communities. Irish immigrants learned English from those whose first language was also not English. Gaelic (both Scot and Irish) was present in the Valley, as was French of les Canadiens. Traces of Irish remain, today, in inflections and expressions known as the ‘Ottawa Valley Brogue’.

Although the ‘Brogue’ is fading from common speech I recall traces in my grandparent’s speech. The town of Shawville was pronounced ‘shovel’, ‘th’ sometimes went missing, replaced by a hard ‘t’, while the ‘t’ was replaced by a ‘d’ (Oddawa instead of Ottawa). Expressions linger such as ‘gidday’, ‘giver yer all’, and ‘be going’. Reminants remain in ‘anyways’ used to end a sentence, rather than ‘eh’, and the use of an inclusive ‘Alls’, Yous’ and ‘let’s get ’er done’(13).

Large Roman Catholic congregations also remain active, throughout the Irish-settled areas. Old cemeteries occasionally display Gaelic on memorials. Ottawa Valley Fiddling and Ottawa Valley Step Dancing have become internationally recognized styles, surviving despite attempts of Penal Law attempts to abolish Irish music and dance. More importantly Irish lives on in the Ottawa Valley, through culture, faith and DNA.

For further appreciation:

The bittersweet tale of an 1830 Irish family’s first Canadian winter is available for viewing at the NFB site. ‘First Winter’, National Film Board of Canada, 1981.

References:

(1) David Rumsey Historical Map Collection, (a)Joseph Bourchette 1815-Topical Map of the Province of Lower Canada, and (b)Joseph Bourchette 1831-Map of the District of Montreal, Lower Canada

(2) Rawdon, The Hills of Home: A History of the Old Rawdon Township, quebecheritageweb.com

(3) The Forgotten Irish? Contested sites and narratives of nation in Newfoundland, Johanne Devlin Trew, Ethnologies (Vol.27, no.2, 2005) re: Irish Newfoundlanders, Wikipedia

(4) A History of the Penal Laws against the Irish Catholics, Sir Henry Parnell, Yale MacMillan Center, glc.yale.edu

(5) The Irish Heritage of the Laurentians, Sandra Stock, Laurentian, quebec.heritageweb.com

(6) John Davis Cantwell MD, A great-grandfather’s account of the Irish potato famine (1845-1850), Baylor University Medical Proceedings 30(3), 2017 July

(7) Knock Shrine, Mayo Quebec, Wikipedia

(8) Gaels of the Gatineau Valley, Danny Doyle, Gatineau Valley Historical Society (Vol45)

(9) Early days in Mount St. Patrick and Dacre, Bill Graham, greatermadawaska.com

(10) Velma, JL Fontena, Some aspects of Roman Catholic service in the land forces of the British crown (1750-1820), University of Portsmouth, @2002

(11) Peter Robinson’s Report on 1823 Emigration to the Bathurst District of Upper Canada (Ontario) Rick Roberts, October 2006, globalgeneology.com

(12) Peter Robinson Settlements 1823 & 1825: A British-Canada Experiment, @ 2018, Derek J. Blout, Lost Branches, LLC

(13) Ottawa Valley Slang: Did you Know the Ottawa Valley has its own Language? (Feb 4/23) Yoair Blog

(14) Lucille H. Camper, Ontario and Quebec’s Irish Pioneers @2018, Durham Press

September 9, 2021

Victims, Traitors or Seekers of Justice:The Bloody Assize of Ancaster (1814)

In 1814, nineteen Loyalists of the Upper Canadian colony faced a charge of high treason against the Crown. Suspicions of their conspiracy and collusion with the United States had been raised during the British/American War of 1812. Eight of those charged were found guilty; and sentenced to being hung, drawn and quartered. This barbaric execution, (the condemned hung near death, cut down with intestines removed and burned, and body dismembered) was intended to serve example to colonists, mostly ‘late Loyalists’, that loyalty to the Crown was to be unquestionable.

The quickly assembled court, called an assize, was presided by three Loyalist judges, all of whom served, at some time, as Chief Justice for Upper Canada, and were from the prominent ruling families of the colony. They were also life-appointed members of the Executive Council which had governed the elected Legislative Assembly of the colony since 1790. The prosecutor was John Beverly Robinson, 23 years of age, also from these same prominent Loyalist families. (1)

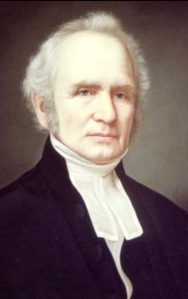

Sir John Beverly Robinson (later in life)

Sir John Beverly Robinson (later in life)Two waves of Loyalist American immigration occurred, post-American Revolution War, from 1777 to 83. (2) The first wave, from 1777 to 83, came in response to severe persecution in the new republic for their loyalty to the Crown. Post-1780 migrants were known as ‘Late Loyalists’ who, mostly, came to gain land. All that was required of these latter loyalists was allegiance sworn to the Crown. The British government hoped to encourage settlement of the colony through generous land grants to offset the large French colony of Lower Canada. After 7 years residence, male Loyalists were given the right to vote for, and even run for membership of the Legislative Assembly.

With American invasion of Upper Canada, in the summer of 1813, loyalty of this latter group became suspect. Any hint of republican sentiment, regarding human rights, introduced suspicion of disloyalty to the Tory Executive Council.

In 1813, during the war with the Americans, extended powers were given to the military. This was the ‘last straw’ to Joseph Willcocks(3), an Irish-born, 5-session elected representative of the Legislative Assembly for Lincoln-Haldimand, Niagara. As assumed opposition leader, Willcocks diligently worked to encourage loyalty of six Haudenosaunee nations to the Crown, broaden availability of schooling and fought to combate the hierarchical Tory nepotism of the Executive Council.

By 1813, far-reaching nepotism of the early Loyalists had come to be known as the Family Compact because of their extensive compacted web of blood, marriage, legislation and business.(4) Large estates and wealth acquisition could not be separated from their political and judicial power. Theirs ties to the Church of England ensured that 1/7th of all surveyed Crown land was held back as clerical reserve for this church.

Dominating through the Executive Council and social connection, the Family Compact influenced lawsuits, and land grants. In October 1806, reopening of the United Empire List, had effectively limited land acquisition to British subjects. Subsequently, they introduced a list of resident aliens, where suspect aliens could be deported by order of any magistrate, if perceived as a threat to security.

Manifest injustice (a legal outcome that is plainly and obviously unjust) was rampant for accuser and judge had potentially become one and the same. Property seized by the sheriff for any manner of crime, from debt to treason, was offered in ‘collusion sale’ to a select group of bidders at below market value.

The American occupation of 1813 presented opportunity to redress this misuse of justice. In the summer of 1813, Willcocks assembled a company of Canadian Volunteers and defected to the United States. Commissioned as a major in the United States Army, his volunteers were involved in a number of skirmishes, foragers and scouts around Niagara. With the capture of Newark (present day Niagara-on-the-Lake) he was appointed police over the occupied town.

Burning of Newark (Niagara-on-the-Lake, December 9, 1813

Burning of Newark (Niagara-on-the-Lake, December 9, 1813In retaliation for one of his volunteers being killed, Willcocks ordered the burning of Newark on December 9, 1813. Four hundred residents (mostly women and children) were left with only the clothes on their back. Their possession and provisions were destroyed before their eyes, leaving them without shelter in the height of winter. Many froze to death; many others starved. His commanding officer, American Brigadier General McClure (5) was promptly relieved of command and dismissed from the US Army in discipline for the act.

Joseph Willcocks, former member of the Legislative Assembly, was found guilty of high treason, in absentia, at the Assize of Ancaster in 1814. On September 4, of that same year, he died from a mortal wound during action at Fort Erie. The man who burned the town of Newark, is buried in Buffalo’s historic Forest Lawn Cemetery, a burial place of notable American heroes.

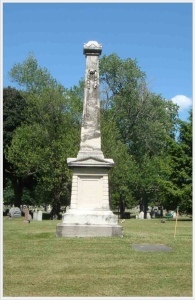

Forest Lawn Cemetery War Memorial, Buffalo, NY

Forest Lawn Cemetery War Memorial, Buffalo, NYAs for the ‘traitors’ of the Ancaster Assize, the death sentence of the 8 was mercifully changed to hanging, followed by decapitation. The execution was carried out July 20, 1814 at the Burlington Heights Barracks. The bodies were thrown into an unmarked grave, close to the gallows, likely in present day Dundurn Park, overlooking Hamilton Harbour. Their heads were placed on pikes and paraded through local villages, as deterrent to future republican sentiment.

One of the imprisoned ‘traitors’, Jacob Overholser, died of typhus in the Kingston prison. He was a simple farmer, illiterate and father of 4. Charged with carrying arms and assisting the enemy, he had actually sought redress from the Americans, while their captive, for setting fire to his buildings and stealing his horses. The only witness to his alibi refused to testify under oath for religious reasons. Furthermore, doubt arose as to his guilt for his accuser was involved in a property dispute with him at the time of the charge. Neighbours raised the money to buy back the seized farm, at the sheriff’s sale, for his surviving family.(6)

Epaphras Lord Phelps

Epaphras Lord PhelpsAnother notable property seizure was the land of Epaphras Lord Phelps. This white secretary and power of attorney for Joseph Brant, Mohawk leader of the Six Nations, was a known American sympathizer. He fled to the United States in response to the charge of high treason, with the assistance of the Mohawks and his land was seized. A protracted legal battle resulted, since the land had been a gift, from Joseph Brant, to honour his marriage with a Mohawk lady, Esther Hill.(7)(8)

The Crown first argued against Esther’s claims, citing she was an ‘alien’, under terms introduced by the Executive Council, unable to hold property. When this was defeated, the Crown argued that the land had only been conveyed to her husband. Under the ‘couverture’ condition of British common law, she was considered chattel, as a wife, and unable to hold property. The Six Nations exerted influence, and the court was forced to cede the land back to her family. Within matriarchal Haudenosaunee society, property passed through the female family line.

Many grievances, caused by the powerful Family Compact influence, persisted until the Mackenzie Rebellion of 1837. Over 800 people were arrested, in this rebellion, with 92 transported to a Tasmanian penal colony, and 12 men hung.

This resulted in Lord Durham’s investigation of these grievances. In conclusion he condemned the Family Compact as “a petty corrupt insolent Tory clique” and put forth recommendations for government reform towards “responsible government” (self-government). The traitors of 1837 were pardoned (those still alive). The leader of the rebellion, William Lyon Mackenzie, was also pardoned and returned to his political career.

Within 30 years, Canadian democracy advanced to form a nation. Lord Durham’s recommendations came too late for those seekers of justice, now lying in an unmarked grave, somewhere in Burlington Heights.

Burlington Heights (1813 and 2021)The Ancaster “Bloody Assize” of 1814, William Renwick Riddell, Ontario History Society, Special Issue: The War if 1812, Vol. 104, No. 1, Spring 2023https://www.thecanadianenclyopedia.ca/en/article/loyalistshttp://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/willcocks_joseph_%E.htmlhttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Family_Compacthttps://www.warof1812.ca/burningofnewark.htmhttp://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/overholser_jacob_5F.htmlhttps://theheartofontario.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Traiters-and-Treason-in-the-War-of-1812-1.pdfThe Work of our Hands, Mount Pleasant, Ontario 1799-1899. A History, Dr.Sharon Jaegar, Heritage Mount Pleasant @2004https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Upper_Canada_Rebellion __ATA.cmd.push(function() { __ATA.initDynamicSlot({ id: 'atatags-26942-613b3e24721b8', location: 120, formFactor: '001', label: { text: 'Advertisements', }, creative: { reportAd: { text: 'Report this ad', }, privacySettings: { text: 'Privacy', onClick: function() { window.__tcfapi && window.__tcfapi( 'showUi' ); }, } } }); });

Burlington Heights (1813 and 2021)The Ancaster “Bloody Assize” of 1814, William Renwick Riddell, Ontario History Society, Special Issue: The War if 1812, Vol. 104, No. 1, Spring 2023https://www.thecanadianenclyopedia.ca/en/article/loyalistshttp://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/willcocks_joseph_%E.htmlhttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Family_Compacthttps://www.warof1812.ca/burningofnewark.htmhttp://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/overholser_jacob_5F.htmlhttps://theheartofontario.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Traiters-and-Treason-in-the-War-of-1812-1.pdfThe Work of our Hands, Mount Pleasant, Ontario 1799-1899. A History, Dr.Sharon Jaegar, Heritage Mount Pleasant @2004https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Upper_Canada_Rebellion __ATA.cmd.push(function() { __ATA.initDynamicSlot({ id: 'atatags-26942-613b3e24721b8', location: 120, formFactor: '001', label: { text: 'Advertisements', }, creative: { reportAd: { text: 'Report this ad', }, privacySettings: { text: 'Privacy', onClick: function() { window.__tcfapi && window.__tcfapi( 'showUi' ); }, } } }); });

May 6, 2021

Regency Garments: Deception of Appearance, Reality of Constraint

Have you ever envied a Recency woman? Prancing about her green English estate, clad as a Roman goddess, jiggling tummy hidden beneath layers of shear muslin, she lived for romance to make life complete.

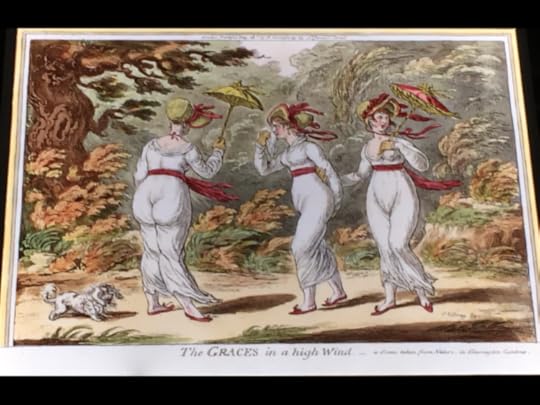

The Graces in a High Wind, James Gillray (1810), (taken at National Museum of Scotland)

The Graces in a High Wind, James Gillray (1810), (taken at National Museum of Scotland)Lydia, youngest and silliest of the Bennet sisters, gushed my favorite lines in the 1995 adaptation of Jane Austen’s book, Pride and Prejudice.(1) “Lord! Denny, fetch me a glass of wine, I can scarcely draw breath. I’m so fat.”

Weight didn’t seem to matter…Lydia was free to bounce and frolic…for plumpness was considered an indicator of health. Portraits of ample maidens in the National Art Gallery confirmed my understanding. ‘Hale’, ‘Bloom’ and ‘Vigour’ were Jane Austen’s complementary descriptions of heroines enjoying ‘food in good company’.(2)

Miss Austen did not write Lydia’s exclamation.

Julia Sawalha as Lydia Bennet, Pride and Prejudice (1995)

Julia Sawalha as Lydia Bennet, Pride and Prejudice (1995)Andrew Davis added it to his 1995 screen adaptation, to illustrate the impropriety of the Bennett girls at the Netherfield Ball. Furthermore, upon researching that era, you soon discover that weight expectations of Regency women were no different than that of present-day. Under those billowing gowns, women were trussed up in corsets, that robbed them of both breath and movement, in effort to create a beautiful silhouette.

A Regency corset (also called a stay), was worn by both rich and poor. Though not as confining as the later Victorian version, it was formed of thick cotton quilting, tightly laced up the back, and with a prominent frontal wooden busk (flat stick of about 1 inch in width), positioned from the breasts to the lower abdomen.

Regency corset (stay), front and back.

Regency corset (stay), front and back.A woman couldn’t dress alone, unless willing to be a ‘loose’ woman, for dressing required assistance of a ‘lacer’. It also left her unable to bend at the waist. (A shortened ‘stay’ was worn by working women of the lower classes.) Excellent posture was assured at the expense of her movement. Significance of the garment’s restraint is implied in Jane Austen’s writing.

Miss Bingley criticizes the Bennet girls’ ‘vulgarity’ and ‘indifference to decorum’ when she extols the attributes of a proper deportment: “…besides all this [a woman] must possess a certain something in her air and manners of walk, the tone of her voice, her address and expression…”

Deportment describes a person’s behaviour and manners. Undergarments constrained woman to enhance deportment. No slouching, leg crossing, thrusting of hips or free cavorting about. A loose fitting drawstring shift, worn under the corset, and two pantelettes (pulled up each leg, split at the middle, tied at the waist) were worn as underclothes(3) under dress and petticoat.

Regency dresses, National Museum of Scotland

Regency dresses, National Museum of ScotlandTrussed up, with crotchless undergarments under thin muslin dresses, Regency woman of all classes were vulnerable.

In Regency England, marriage suspended the legal existence of a woman, consolidating her into that of her husband. She became a ‘non-person’ in the eyes of the law, a Feme Covert, where her legal right and obligation were subsumed by those of her husband.(4) ‘Covered’ by her husband, they were considered one person. As a result, all compacts were made void upon marriage, for her husband could not grant her anything, or even enter into a covenant with her for that would suppose her a separate entity, which she was no longer. The only exception was the Queen of England (both as queen consort or queen regnant).

A Feme Sole, an unmarried adult woman, was able to act on her own regarding estate and property—that is if she was fortunate enough to inherit.

Just like the Royal primogeniture laws, which were only altered in 2013 by the Succession of the Crown Act, male-line inheritance governed distribution of assets and titles.

Austen’s Pride and Prejudice follows the Bennet daughters’ desperation, for they have neither inheritance nor brothers to inherit. Their family estate will pass to a distant cousin, Mr. Collins, who condescends to marry one of the daughters to keep them from ruin, upon their father’s death.

This vulnerability has yet to be corrected. We can cast aside a baffling assortment of garters, sanitary belts, girdles, underwires, … and maintain respectability. We can even pursue a career or profession. Prevailing male primogeniture still governs inheritance of peerage and property. (5)

A deception of appearance remains.

I hurried upstairs, stripped off my clothes, including the cursed corset, and thrust them into the cold hearth to burn later. — Janet Blythe(6)

(1) Pride and Prejudice, Jane Austen, originally published 1813

(2) Jane Austen believed beauty could come in every shape and size. What else can she teach us about wellness? Bryan Kozlowski, March 12, 2019, Washington Post

(3) Corsets and Drawers: A Look at Regency Underwear, June 17, 2011, janeausten.co.uk

(4) Commentaries on the Laws of England, William Blackstone, Clarendon Press at Oxford, 1765

(5) Ladies first in Tory plan to abolish male primogeniture, Tom Newton Dunn, February,20, 2021, The Times

(6) Catherine Grove, Never Far (distributed through IngramSpark) 2020

April 11, 2021

Descendant of a Canadian Veteran

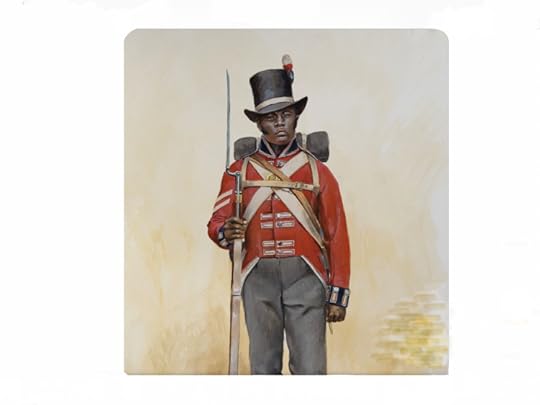

With the American Revolution, Napoleonic Wars and colonial expansion, British Military needed desperately to augment their forces. In the 1790’s Black soldiers were proposed as a possibility, strong men suited to harsh colonial climate.(1) In addition, a well-disciplined armed force of former slaves would encourage slave rebellion in the new American Republic.(2)

Lower ranks were filled with Creole and African slaves, purchased from West Indian plantations, or ‘rescued’ from the middle passage on their transportation to America. After much debate, under the Mutiny Act of 1807(3), Black soldiers were considered freemen, recognised as any white soldier, with pay, pension and land allowances in exchange for service.

In 1809 a young black man was plucked from the streets of Bridgetown, Barbados. He was only 15 and he remained in the military for 29 years, serving in the Canadas. From the War of 1812, through to the Mackenzie Rebellion (1837-38), he defended the British Colony of Canada.

He married an older Irishwoman, was awarded an allotment in the Ottawa Valley, which he registered in his wife’s name, and left at least 4 children, from whom I descend.

This was the beginning of my family’s Canadian Military service.

My grandfather was wounded at Vimy Ridge during the First Great War, the ‘War to End All Wars’, a great uncle lies buried in the Somme. Other’s returned to have sons answer the call to serve in the Second World War. My father endured North Africa, Ortona, Groningen, Germany, serving in the reserves until the Korean War. An uncle remained in the services until the mid-60’s.

I’m a product of the ‘Baby Boom’ post-war celebration of return to peace. I grew up in a society, shadowed by war, attempting normality. The Canadian Legion was our social center.(4) Cousins held their wedding receptions at the Legion Hall. Funerals were catered, grave stones provided and scholarships funded by the Legion. Every Christmas, the Legion Hall held a much-anticipated party for children, where a ruddy-faced Santa gave out inexpensive gifts, and we played musical chairs, while mothers served up pickle and egg salad sandwiches.

Our TV was ‘donated’ to cover my dad’s bar bill. It sat in the Legion bar for 10 years watching over the smoke-filled hall where veterans drank from snub-nosed bottles, sharing the unspeakable. They’d survived, this was their trauma counselling, for PTSD was not acknowledged. The Legion was always there for them; a home for the veteran in every Canadian small town.

The bleeding neighbour, running naked through the streets mid-winter, brandishing a knife, was quickly subdued, taken away to rest, and his family supported. Drunken outbursts were forgiven, fights broken up, nothing was ever spoken afterward, for we endured stoically.

My uncle displayed a German grenade and pistol in his glass liquor cabinet. A boy would have known the model, boasting with bravado. Boys boasted of their Dad’s battles. I didn’t.

“Did you ever kill anyone in the War, Daddy?” I asked instead.

“Hell no,” he assured me, “I hid my arse and tried to stay alive.” Yet, he refused to hunt anything other than partridge, citing, “Looks too much like a human!”

And then there was that thick German leather belt that he slapped against the wall, whenever we were rowdy and disrupted his peace. “Better the wall, than you,” he‘d snipe.

Years later, my sister inquired of the Canadian War Museum if they would be interested in the ‘Belt’. They declined. “We have boxes full of their war trophies—they all brought something back.” Stripped from the dead, proof of survival, something to pass on to the next generation.

Winter Road, Northern Quebec

Winter Road, Northern QuebecSummer vacations were an adventure led by a man whose fear had been burned out of him. Without planning we set off for two weeks, driving ‘winter roads’ deep into the bush, sleeping in our car where tenting wasn’t possible. Thousands of miles we travelled, crossing into the ‘States’, dropping in unannounced on veterans. North America was a safe open road.

My father was fascinated with the War of 1812. Annually we visited Canadian war sites, giving respect to suffering endured, on our land, over a century earlier. He’d seen war’s cost in the villages of Italy and Holland. He knew what had transpired here, in Canada.

Fearlessly my father also took us to Harlem and a burning Detroit in the mid-1960’s. I now understand this as homage to a young black man, long buried in the Ottawa Valley, who fought for dignity and opportunity. A man from whom many veterans descend.

I am a descendant of a Canadian Veteran.

I submit, that although the Canadians are not a war-like people, they are a fighting people, none better. — Leslie F. Hannon(5)

National Army Museum, nam.ac.uk. The West India RegimentsRosalyn Narayan, Creating insurrections in the heart of our country: fear of the British West India Regiments in the Southern US, Taylor & Francis Online (Vol.39, Iss. 3), August 21, 2018Dr. Lennox Honychurch, Slavery Reparations: An Historian’s View, BBC Caribbean.com, March 30, 2007The Royal Canadian Legion, legion.caLeslie F. Hannon, Canada at War: The Record of a Fighting People, McClelland and Stewart, 1968March 23, 2021

Interview with Jenny Burr

JennyEBurr Writes—A blog featuring writing, teaching, life, and more.

Interview with Author Catherine Grove, November 2, 2020

Today I am welcoming Catherine Grove to JennyEBurr Writes to talk about her two historical novels, Never Forget which was published in 2019, and Never Far which was released in the summer of 2020. Catherine, describes herself as a “history buff” who loves researching her family’s roots, but also the lives of others. She not only writes about the past, but, when possible, she experiences it.

Tell us a bit about your first book, Never Forget and your second book, Never Far.

They are the story of a resourceful frontier-raised Canadian woman who defies family ambition schemes to pursue her independence in Regency England, post-war of 1812. Originally, they were one book. I separated the plot, at a coming-of-age choice, advised that I was not known enough to publish a fat book. Both books can stand alone and stir the reader for more.

What intrigued you about this time frame in Canadian, American and British history that piqued your interest in using this historical time frame in your novels?

Not much is recorded in Canadian history books of the period between the War of 1812 and building of the Rideau Canal. Yet there was immense upheaval caused by climate (the ‘Year Without Summer’) and within society (the early industrial revolution, Land Closures in Britain, Penal Laws in Ireland, etc). Slavery had yet to be abolished, migration, American opportunists poaching Crown lands of timber, steam replacing manpower—it was an exciting time with plenty of ‘shenanigans’.

How did you come up with the titles?

I like to keep things simple; in simplicity there are multiple meanings.

Which came first for your books, the history you wished to explore or the story line?

The character comes first, driving the plot of the books.

Let’s explore this comment further. With respect to your main character in Never Forget, explain how you decided on Jane Blythe as the main character and how her personality and character move the plot forward in Never Forget.

Throughout time women have surmounted to make the world a better place: Christian activist Josephine Butler (mid-1800’s) worked with street women and child prostitutes, feminist Mary Wollstonecraft (late 1700’s) argued for equality of women, theologian Julian of Norwich (1400’s) wrote the first English book (Revelations of Divine Love) by a woman, Loyalist Mary Hoople (late 1700’s) healed with traditional Indigenous practices acquired in her upbringing as a captive of the Delaware people.

Janet Blythe is inspired from real incidences and people. I first saw Janet, the year before Never Forget begins, living on the Niagara front lines of the bloody War of 1812. She opened her cabin door to wounded British soldiers from the nearby Battle of the Forty; out of necessity they slaughtered her milk cow to eat.

Then, in Never Far, how does your main character’s independence and spirit cause difficulties for her?

Impulsive and brusque, Janet won’t keep quiet to injustice and she doesn’t quit—even when seemingly defected. She lives with the consequences of her actions and judgements; just as we must. Loving deeply, she draws a loyal following of those who see beyond her prickly exterior, for they know she can be trusted.

How long have you been interested in history? Explain how you did your research for both of your books.

Grandparents passed on to me an oral history family tradition. Researching their tales revealed truth is stranger than fiction. With Never Forget/Never Far, the character’s world (culture, politics, legal status, clothes, faith, diet, world events, transportation, etc.) determines her choices. Historical accuracy directed my decision to Indie publish.

Explain how you research for historical accuracy? (ie examples of resources, first person accounts via journals or diaries, news clippings, etc.)

I have a broad approach. As an avid history buff, I’m a member of historical and archaeological societies, attend events, use their archives, and visit local museums (both here and overseas). Curators and historical re-enactors are invaluable for their understanding of daily life. I peruse blogs on clothing, culture, climate, toilets, tooth brushes, etc. and have sought legal advice (for Documents and Agreements referred to in story) to build an accurate portrayal of the time.

My ‘fun’ is walking the places of my stories. Last Sunday, my husband and I roamed a nearby town, reading Blue historical plaques, identifying buildings from an 1838 map, noting events eluded to on tombstones. I’ve stood at the base of the escarpment falls and climbed the path where Janet and James’ raced. I’ve walked through English estate houses, sat in an Irish immigrant ship, lit a candle and prayed in the chapel described in Janet’s world. (With present Covid restrictions on travel, Google Earth has been helpful.)

I recommend ‘The Timetables of History’ by Bernard Grun, as reference for worldwide events from 4500 BC onward. What is going on in the world is essential, for we do not live in isolation.

When you wrote your first book did you know that you might be writing others which might be either stand alones or as part of a series? No, it depended on where the character went. I’ve written other books (1800’s, 1940’s, 1960’s) I’ve yet to publish. Some may become series, spanning generations of the character.

Do you write full time or part time?

I’m a storyteller, compelled to create full time, and get grumpy if I don’t.

What do you love about writing historical fiction and what do you find challenging?

I love to travel back in time. Balancing creativity with research can be difficult.

Have you always wanted to write? Did you have anyone who influenced or encouraged you to write?

No. I have a vivid imagination, aided by growing up without a television and reading a lot of biographies and mysteries. My father-in-law is a self-taught published writer who encouraged me to put my stories to paper and “Write large—don’t hold back!”

Do you have a favorite author or authors? What do you enjoy about their writing?

John Buchan, a former Governor General of Canada. I enjoy the mystery, suspense and adventure he brings to his stories from his life experiences as an intelligence officer, journalist and politician.

Do you have anything which you would like to share with aspiring authors?

Don’t doubt yourself. A craftsman always improves.

Is there anything else you would like to share?

Knowing my stories have touched someone is rewarding. Please write a review.

Published by Jenny E Burr, the author of Living God’s Grace (2019,2020-available from Amazon). Jenny is an amateur cell phone picture hobbyist, a published writer, an avid reader, a teacher, a wife and mom, living in Ontario, who blogs at: jennyeburrwrites.wordpress.com.

October 28, 2020

Cabin Fever in Covid Times – What Can We Learn from Canadian Settlers?

Days are getting shorter, temperature is falling, as winter creeps towards us.

We are a Northern people. Danes have their Hygge, Norwegians their Koselig and Canadians, old and new, have a rich, diverse heritage to draw from. We can take heart, from the ‘lessons learned’ by our Canadian Settlers, draw principles to overcome challenges, and face a long winter, temporarily apart in an imposed COVID-19 isolation.

“…my love for Canada was feeling very allied to that which the condemned criminal entertains for his cell—his only hope of escape being through the portals of the grave. The fall rains had commenced. In a few days the cold wintery showers swept…and a bleak and desolate waste presented itself…”(1).Susanna Moodie’s lament of her first winters in Ontario, 1837, illustrates the struggle of English settlers facing a harsh Canadian winter. They had yet to learn from the Indigenous people, as had French settlers.

During their first winter on American Shores, in 1604, more than half of the French settlement died of scurvy. Another winter loomed. In Spring, their leader, Samuel de Champlain moved the settlers across the Bay of Fundy to the northern shores of Nova Scotia to what was hoped a better site. And he came up with a plan to endure the brutal winter. Believing the fatal illness was the result of ‘idleness’, he established the ‘Order of Good Cheer’.(2)

Modeled loosely on European Chivalry, the Order mandated fellowship and good cheer through weekly feasting and entertainment, from November to March. Through festivities, decorations, competitive hunting and fishing, he hoped to keep spirits up. Each week was hosted by a different member of the more than 30 men in the company, who prepared and planned activities and food. Local Mi’kmaq people were invited who graciously supplied most of the fresh food. The regular feasting fortified settlers’ bodies and minds throughout the long winter. Inclusion of the Native diet greatly helped.

Cedar tea had already been introduced by the Iroquois to an earlier French explorer Jacques Cartier in the winter of 1535-36. Icebound, on the St. Lawrence River, at an Iroquois Village of Stadacona (present day Quebec City), his men slowly succumbed to scurvy.(3) As an offering of peace, the Iroquois Leader, Donnacona, prepared and offered them a tea made from the leaves of a white cedar tree. Preferring to die quickly from poison rather than slowly through scurvy, Cartier drank it and soon felt better. Within 8 days the men were restored.

In the spirit of adventure, however, these later adventurers consumed unfamiliar foods, and participated in outdoor activity with good humor. Adaptation to their New World rather than imposition of expectation contributed to their survival. Mental health improved and bodies strengthened.

Four winter activities they learned from the Indigenous Peoples are still enjoyed in Canadian Winter.

Hockey: Mi’kmaq skated on animal bones tied to their feet, shooting pucks of frozen apples and sturdy sticks.Tobogganing; Although used to travel and transport across deep snow, toboggans converted to fun on snowy hills.Snowshoeing; design of shoes varied with terrain and First Nation, but allowed freedom amid heavy snowfall.Ice Fishing; First Nation people fished year-round, chipping holes in the ice and dropping down a lure-on-line.

The population of the early French Catholic settlement quickly grew helped by the influx of 500 Filles de Roys (daughters of the King). These were single women of good character, sponsored by the King of France, to marry decommissioned French soldiers and Habitants of the new colony.

The Canadian climate was vastly different from the milder France, but the open-minded settlers adapted clothing and lifestyle to that of the Indigenous people, dressing warmly in mukluks, furs and warm knitted tuques, mitts and scarfs. Colour was vibrant, if only to prevent being mistaken for game in the bush.

Warmly dressed, snowshoed and with toboggans Canadiens moved freely throughout the long winter season. They also retained the Joie de Vie (Joy of Life) attitude of the Order of Good Cheer in both daily life and their faith. French Canadian chapels are a celebration of drama and colour. Icons, relics and stained glass can be gruesome, but rich woods, smells of candles and incense, and hues of blues and shining gold trims warm the soul. While mass was said in foreign Latin, these objects translated faith’s intangibles into the sensory.

Christmas was primarily a religious celebration, in the French colony. Beginning with mass on Christmas Eve, it culminated January 6th, with mass on the Feast of Epiphany commemorating La Fête des Rois—the visit of the Three Wise Men to the Baby Jesus. Within these 12 days, the spirited Canadiens packed a grand season of good cheer.

Upon return from Christmas Eve mass, they held a Réveillons—an all-night “awakening” party—with feasting, toasting, dancing, story-telling and merry-making until dawn.(4) Food was important: Tourtière (meat pie made with pork, beef and veal), Ragout des Pattes de Couchons (tender pigs feet stew), Cretons (spiced pork and lard), roasted root vegetables, Tartes aux Sucre (maple syrup pie), along with generous cups of wines, spirits and beer. This was high-fat feasting that met winter’s demands.

Throughout these 12 days, they visited and gave modest gifts. New Year’s Day was more popular that Christmas, with gift-giving from Baby Jesus (not Santa) and the Head of the household praying a Blessing of Favor over the household for the coming year.

Winter carnivals followed after Christmas, continuing throughout the pre-Lenten season. With hunting and ice fishing competitions, canoe racing across icy rivers (a mix of paddling and foot races over icy hazards), snowshoe races, snow sculpturing the cold and isolation of winter was tamed. Come Spring’s warming, ‘sugaring’ season began, with harvesting of maple sap to be boiled down to rich syrup. Hot syrup, hardened over snow into taffy or poured over grill cakes with beans, was celebrated in winter’s snows.

At Lent, frivolity shut down for 40 days in observance of Jesus’s atonement for sins at Easter. Even that somber week was filled with dramatic rituals, such as ashes worn on foreheads, candlelight church overnight silent vigils and religious parades.

After the fall of French Canada, in 1759, English settlers poured into the now British colony, primarily in the west. Slowly they accepted clothes, diets and customs more suitable, to their new circumstances.

The Scots brought with them Hogmanay(5) traditions to welcome in the New Year. Celebration involved cleaning the house, top to bottom, to ritually relieve its inhabitants of unwanted burdens. At midnight of New Year’s Eve, the first to enter the house—the ‘First Footer’–was welcomed with drink of whiskey. He brought a foodstuff gift, a symbol of blessing to come. Fire (a residue from the pagan pre-Christian origin of the festivity) played a significant part, with either a torch procession, or a grand bonfire.

The English also had their traditions. With the French, they shared an observance of the Twelfth Night. It was not a religious tradition, for them, but a peculiar role-reversal rite.(6) A cake was the center of celebration, with a bean baked in. Everyone partook, with the one receiving the piece with bean was declared royalty for the evening. This role reversal could sometimes play out on grander scale, with cross-dressing and class-lines between servants and masters ignored for the night. The tradition of ‘Servant’s Ball’ was embraced, with masters welcoming the servants into their home for the evening.

The Christmas tree was not yet a part of Canadian culture, only arriving with upper classes during the Victorian Era. But greenery was brought in to cheerfully decorate cabins, filling air with scent. From the end of January until Maudy Tuesday (and the Pancake supper) before Lent, settlers warmed their heart and hearth with festivity, light, and good food. Expectation adapted to their circumstances, as they enjoyed what was readily available—the snows of winter. Old was not thrown away, but retained along with that which bettered their world. They did not just survive, but thrived.

In this time of Covid we also face an uncertain dark winter with isolating physical-distancing and limits on social gatherings. So too, we must adapt, as did these settlers. For urban dwellers this presents a greater challenge than those of spacious suburbia and rural communities. Economics also are a factor, but overcoming principles from the past remain the same: Mental and physical wellbeing are essential.

Food feeds not just the body, but the senses. Use of light to combat seasonal depression is well-documented.(7) Spirituality and faith also contribute positively to mental health.(8) Colour and scent, also. This blog is no substitute for sound medical treatment.

Canadian settlers lived actively, under the winter sun. They enjoyed a simple faith, in good doses, interspersed with festivity and fed the sensory. With an open mind, they changed up roles, schedules, and embraced new clothes, foods and traditions.

Whilst our world is not so simple, we do as those of the Order of Good Cheer, choose our reality and adapt.

Although socially-distanced and masked we can enjoy the outdoors, window-shop under street lights, picnic in the snow, play frozen Frisbee-golf, and ‘toboggan’ on green garbage bags in the winter sun. Ice skating at city parks with second-hand skates, in vibrantly colored Value Village outfits, opens up a new world. Greenery grown in cardboard egg cups on window sills, from tomato sandwich bits, or avocado pits brings unanticipated life. Christmas lights or indoor Fairy lights can stay lit up all winter long.

Sipping maple syrup sweetened coffee, we can write physical letters, phone home, DM comments or Zoom group meals. Though travel is restricted, we can try international take-out foods, learn a few phrases from You-Tube and self-study their history and politics. We can learn to crochet a throw for a care-home, and have a pet guppy or two (same sex), in a fish bowl, join an on-line book club, or passively observe a religious service. We must be open-minded to the possibilities.

Most importantly, we can be kind, not just to others, but to ourselves. These challenging circumstances can be overcome, as others learned before us. We are Canadians.

(1) Susanna Moodie, Roughing It in the Bush; Life in Canada, New Canadian Library@1989, McClelland & Stewart Inc.

(2) The Lieutenant Governor Nova Scotia, FAQ (it.gov.ns.ca) Order of the Good Time. @2015 Province of Nova Scotia.

(3) Nancy J. Turner Indigenous Peoples’ Medicine in Canada, The Canadian Encyclopedia, May 1, 2019

(4) tvo.org, Daniel Kitts, Why French-Canadians kick off Christmas with an All Night Feast, Dec 23, 2016

(5) Barbara Greenwood, A Pioneer Story, @1994, Kids Can Press

(6) Tessa Boase.com, The Strange Ritual of the Servant’s Christmas Ball

(7) Light Therapy, Mayo Clinic, mayoclinic.org

(8) Dr. Deborah Cornah, The Impact of Spirituality on Mental Health: A review of the Literature, mentalhealth.org.uk

October 8, 2020

Indigenous Healing Knowledge Adopted by European Settlers in Upper Canada – early 1800’s

“From my training with Soujeesh, the Mohawk Healer, I felt sure this procedure could only push him closer to death…” Janet Blythe, 1815, Never Far

Plants and natural materials, considered medicinal ingredients, promoted replenishment and balance(1) for the sick among the First Nations people of North America. This healing philosophy, fostering therapeutic effects on the body, was extended to Europeans when they became sick after arrival in Canada. Treatments were mostly edible, passed down by Healers from the previous generation. Healing resulted from consuming the plants they harvested and prepared in anticipation of ailments to be treated.

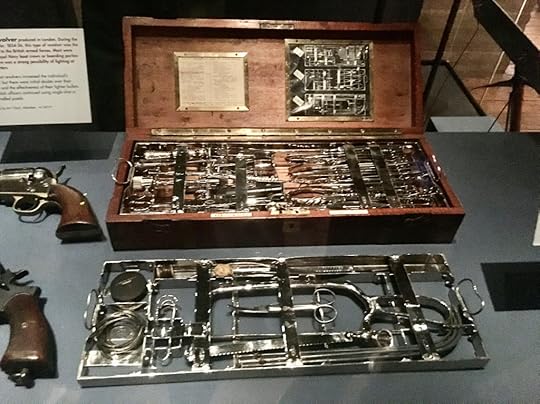

In contrast, the medical care of European physicians of the 1800’s (and earlier) routinely applied bloodletting by attaching living leeches to the skin their patients. Existing belief was that toxins in the body must be siphoned off through systematic bloodletting to prevent or treat infection and disease. Sometimes the application was so exuberantly applied that the patient succumbed to the bleeding.

Jacques Cartier spent the winter of 1535-36 icebound, on the St.Lawrence River, at an Iroquoin Village of Stadacona (present day Quebec City).(2) One-by-one his men grew weaker with incapacitating joint pain, bleeding gums and bruised discoloured skin. The cause was then unknown, but, as a sailor he recognized the onset of the dreaded scurvy, that could sometimes kill up to 50% of the crew on a long sea voyage.

As an offering of peace, the Iroquois Leader, Donnacona, prepared and offered them a tea made from the leaves of a white cedar tree. Preferring to die quickly from poison rather than slowly through scurvy, Cartier drank it and soon felt better. Within 8 days the men were restored. Unfortunately, come Spring, Cartier took Donnacona and 9 others of his village back to France to meet the King of France. All but one, a young girl whose fate remains unknown, died in France.

In France, they would have encountered small pox, measles, mumps and other ailments for which they had no immunity. They also had no access to familiar plants and therapeutic materials.

Eventually these diseases would ravage the Canadian Natives People, but first another mysterious and peculiar sickness was imported, primarily to the Niagara and Rideau regions of Upper Canada. Fever and Ague, a malaria characterized by intermittent chills, fever and eventual anaemia, erupted sometime around the 1780’s, disappearing around the 1840’s. Now known to be carried by mosquitos (genus Anopheles), it was either brought to Upper Canada by infected British regiments from the disease ridden Caribbean colonies, or by United Empire Loyalist relocating from the southern United States(3).

Commonly referred to as the Swamp Fever, under the mistaken belief that it was the result of bad swamp air, it affected more than 60% of settlers in Upper Canada. Another mistaken belief was that the Native Peoples were immune to it. They were not, and also suffered. But they had already learned to reduce their exposure to the carrier culprit, the mosquito(4). Smoke of smudge fires repelled the pesky insects, as did tossing sweetgrass into campfires fire, coating one’s skin in mud and setting up camp in drier areas where the mosquitoes did not breed(4).

In the 1790’s Col. Stephen Burritt having cleared some land near the Rideau River and built a shanty, was stricken with Ague, along with his wife. Laying helpless for 3 days, without fire or food, they would have died had not Native People, traveling through, saved their life.

Leaves and root bark of the Sassafras tree (also called the Ague Tree), were boiled in a tea and consumed to address the symptoms. The suffering settlers did not know that Sassafras had carcinogenic effects, but in the short term, it did provide them some relief.(5)

Settlers, mostly refugees, had little choice but to persevere and heed the medical wisdom of the Native People. Those providing European style medical care had little to offer since they were mostly demobilized medical surgeons, with skills acquired on the battlefield. Ill-equipped to meet the needs of the settlers, they were trained to provide immediate medical care on the battle field. Amputations and cauterizations were their speciality, not long-term care, specifically infection protection.

During the War of 1812, Tecumseh, the Mohawk Military leader, was accompanied by a Shawnee healer, to address the needs of his forces. Upon observing the slow healing of wounds sustained by Thomas Vercheres de Boucherville at the earlier Battle of Monguagon in Michigan, the services of his healer was offered and cautiously accepted.

“My Indian doctor returned the next day and started with his herbs. Ten days later the wound was healed and I was able to resume my duties,”(6) Vercheres was pleased to report.

The willingness of those European military doctors to implement Native medical practices is an example of cross-cultural exchange. The Settlers were already aware of the benefit.

Mary “Granny” Hoople was the first “doctor” in what is now Stormont, Ontario. She learned traditional Native healing practices when taken prisoner by the Delaware people, as a child. She applied this knowledge, when she came to Canada as a Loyalist, before the appearance of formally trained physicians.(7)

As did “Aunt” Betsy Stark, first white woman born in the Clarendon Township of the Ottawa Valley. Little is known of how this pipe-smoking trouser-wearing woman acquired her special healing ability, but with faith, she shouldered the medical emergencies of this remote community. Though she was the mother of 8 children, most of the children of the township can credit their arrival with her help.(8)

A reference to Laura Secord should be made here, because of the inferences made. While nursing her wounded British husband (not yet recovered after a year), she overheard plans being made by American soldiers occupying her home and undertook a brave trek to give a warning that undoubtably contributed to Canada remaining an independent democracy. That local Native people both recognized and assisted her indicates an ongoing relationship of mutual benefit.

Neither Women’s history nor that of the Indigenous people was considered worthy of note at this earlier time. Little has been recorded of their lives. Every Laura Secord’s contribution went unrecognised until 1860 when, destitute and widowed, she was awarded a paltry 100 pounds ($10,000 CDN equivalent today) for her contributions to the war. Therefore, we must glean from what has been recorded, and infer from what is left out.

Although Healers Janet Blythe and Soujeesh, her Clan Mother, of my books Never Forget and Never Far, are fictional characters, their story is inspired by actual circumstances around the settlement of Upper Canada. I have read ‘between the lines’ in my research and brought forgotten/omitted heroic lives into reality. Warrior Women deserve to be honored.

Julian A. Robbins, The International Indigenous Policy Journal, Vol.2, Issue 4, Article 2, October 2011, Traditional Indigenous Approaches to Healing and the modern welfare of Traditional Knowledge, Spirituality and Lands: A critical reflection on practices and policies taken from the Canadian Indigenous ExampleNancy J. Turner Indigenous Peoples’ Medicine in Canada, The Canadian Encyclopedia, May 1, 2019 Charles G.Roland, Malaria, The Canadian Encyclopedia, January 2015Alex Berezow, Sweetgrass: Like DEET, Traditional Native American Herbal Remedy Acts as Mosquito Repellant, American Council of Science and Health, November 2, 2016Charles G.Roland, MD Health and Disease among the early Loyalists in Upper Canada, Can.Med.Assn. Vol128, Mar 1/83Gareth Newfield, Surgeons of the 41st Regiment of Foot during the War of 1812, The 41st Regiment of Foot, Canadian War Museum, 2007Upper Canada Village Cemetery-Hoople, findagrave.com Mary “Granny Hoople” Whitmore HoopleLaura May Harris, Pastures Green, 2008, Lulu PressApril 13, 2020

An Unwelcome Visitor

The next day the unfortunate creature was shaking with the ague…During the cold fit, he did nothing but swear at the cold, and wished himself roasting; and during the fever he swore at the heat and wished that he was sitting, in no other garment than his shirt, on the north side of an iceberg…(1)

Susanna Moodie 1835, Roughing it in the Bush

Swamp Fever (Ague & Fever)

Susanna Moodie’s plucky account of an obnoxious house guest belies the seriousness of the scourge of Ague in Frontier Ontario. On the previous evening their unwanted guest had accompanied her husband fishing; Within hours he was consumed by another unwelcome guest—Swamp Fever—that would plague him for years. The symptoms of Swamp Fever (commonly referred to a Ague & Fever) were recurring bouts of sever fever, shaking chills and anemia that severely weakened the victim against other infirmities.

Ontario Frontier settlers mistakenly believed the Swamp Fever malaria was caused by ‘putrefaction’ from bad(mal) smelly air(aria) around swamps. Only 80 years later, in 1907, would a sporozoite micro-organism, transferred through the bite of mosquitos, be identified as the cause. By then the scourge had all but disappeared from Upper Canada along with the large tracks of marshy land and dense canopied forests that provided breeding grounds for mosquitos. Possibly the increase of livestock on cleared lands also provided better feeding than the local farmers.

From the 1780’s to the 1840’s Loyalist, British Military and European settlers faced an ever present spectre of Ague. The Fever was so common during that time that is was considered rare if a newcomer failed to acquire the disease within their first year in Upper Canada. In 1790, two out of three people in Niagara were reported to have the Ague. The settlement in York (1803) also reported a constant struggle with malaria.

But where and how did it come? One theory is that British soldiers, previously infected with malaria in the Caribbean, transferred it to the local mosquito population upon posting to Canada during the 1812 War. But the United Empire Loyalists of the previous generation also reported occurrences of the ‘shaking ague’. A similar malaria was reported in Massachusetts so possibly the disease may have been imported with them.

Col. John Simcoe, commissioned as the first Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada in 1791 and his wife Elizabeth Simcoe suffered with the Ague throughout his tenure. His critic and underling, William Jarvis, resenting being posted to the York settlement, cruelly wrote,“Col. Simcoe is at present very unwell Niagara and if he has a good shake with the ague, I think it will be justice for his meanness in dragging us from this comfortable place (Kingston) to a spot on the globe that appears to me as if it has been deserted in consequence of plague (York).”(2)

Regarding Rideau Township and those rugged Loyalist lumbermen who settled in this boggy hinterland of eastern Ontario, it is known from the Report of the building of the Rideau Canal, 1828 and 1835 were particularly bad years for the Swamp Fever. Malaria epidemics were so severe that construction of the Rideau Canal came to a standstill in 1828, with an infection rate of 60% and death rate of 4%. Coincidentally these winters also saw higher temperatures than normal that continued throughout the summer with high precipitation.(3)(4)(6) Settlers in others years were also not spared.

In the 1790’s Col. Stephen Burritt travelled by raft to the rapids that now bear his name. Having cleared some land and built a shanty, he was soon stricken with Ague, along with his wife. Laying helpless for 3 days, without fire or food, they would have died had not Native people, traveling by, saved their life.

To the south a few miles, Volney Waldo was similarly stricken with his wife and child in 1824. Prostrate for three days, a frontiersman in search of a light for his pipe found them, and nursed them back to life.

Rev. William Brown (1804), of Wolford, was plagued was persistent fever. While conducting a religious service he was stricken and prayed for deliverance. Coincidently the fever lifted, he preached one of his best sermons ever and was troubled no more with Ague that season.

Most sufferers were not so fortunate. Further to the south, the village of Gananoque endured an epidemic in 1826-27 that nearly decimated the village. Six of the MacDonald household died. Business in the village was suspended.(4)

Those providing medical care had little to offer but care.(5) Demobilized medical surgeons, whose skills were mostly acquired on the battlefield, were ill-equipped to meet the needs of the settlers. Although Quinine sulfate was found to be an effective treatment, few had access or could afford it. So was Peruvian bark, referred to as the ‘bark’, also expensive and rarely available. Infusions of sassafras did help with some symptoms.(6) Otherwise the settlers faced a constant struggle. Amulets and charms, drinking ‘bitters’, and bleedings to ward off the ‘invisible’ scourge.

Present day Marlborough Forest has 8000 hectares of public forest. Under the thick canopy of trees, horseflies and mosquitos are reported to be a terror. Many streams of Rideau Township feed back into broad swamps and scrubby thickets. Within the Forest, pioneer burial cairn memorials bear witness to the hard existence of those early European homesteaders before the land was somewhat subdued.

Settlers were rarely warned of the scourge they faced with this plague. Those who came to Canada had little choice but to come and endure the unknown. I take courage from these pioneers.

Today, we also face unknowns. We are fortunate that there are scientists striving to establish solutions for the challenge we now face. We have supply systems in place to ensure food and fuel continue. We have dedicated medical professionals to give equitable care when needed. And our elected governments continue to collaborate for a solution for the crisis we now face.

We also have bug spray.

Catherine Grove

References:

Susanna Moodie, Roughing it in the Bush, McClelland & Stewart, 1989Simcoe and the Birth of Upper Canada, Upper Canada History.caThe winter of 1827-28 Over Easter North America Climate Change (2007)History of Leeds and Grenville Ontario from 1749-1879Charles G.Roland, MD Health and Disease among the early Loyalists in Upper Canada, Can.Med.Assn. Vol128, Mar 1/83A.Murray Fallis, Malaria in the 18 and 19 Centuries in Ontario, University of Toronto Press