Lancelot Schaubert's Blog, page 83

July 10, 2020

Stripped

Arantxa Hernandez over at The Showbear Family Circus - Lancelot Schaubert's and Tara Schaubert's liberal arts circus. said ::

See where the sun rises,

where rays sneak through bamboo branches and reveal the royal Avila,

where your guardian angel was born

and flew away before you got to meet him.

Walk into your home,

where your father and mother,

where your sister and brother,

drown in the numbness of a dinner table

with no conversation.

Go up your stairs,

smell the acrid humidity in your closet as

you clear your damp clothes and yellow post-it:

I’m sorry. We just can’t afford it.

Not yet.

Enter the palace of scarcity,

smell the desperation of your mother’s half empty plate,

of lines searching for food, medicine.

Your ID number is not 3, the register says.

You can only buy rice if it ends with three.

Step over the trash,

the sorrow,

the anxiousness dried in licked candy wrappers.

March through crowded streets,

Smell the vinegary scent of defeat as you

shout, curse, spill all your rage through

layered body sweat

and blurry protest prints, used as shields.

Choke on tear gas until you feel like

dying.

Watch the withered Avila light up in majestic flames,

Think of your guardian angel

celebrating inside someone else’s body

as you step into your quiet home, empty handed.

Read more posts like "Stripped" at The Showbear Family Circus.

July 9, 2020

rooftop rain dance

Lauren Schaubert over at The Showbear Family Circus - Lancelot Schaubert's and Tara Schaubert's liberal arts circus. said ::

Read more posts like "rooftop rain dance" at The Showbear Family Circus.

July 8, 2020

“Anne Hathaway’s House”

Kristina Heflin over at The Showbear Family Circus - Lancelot Schaubert's and Tara Schaubert's liberal arts circus. said ::

How many times did shutters open

to your step upon this path?

Did you walk or count your horse’s gait

composing as you rode

to Anne Hathaway’s house?

Was it the sun that smiled

upon your pilgrimage

hastening you on your way?

Or did the moon light the road that wound

to Anne Hathaway’s house?

With the words that flowed

from your enchanted pen and lips

it is no wonder that ere long

your home became known

as Anne Hathaway’s house

Did she know then?

Did she know that rural life

would never satisfy the man for all ages?

and already his steps were leading

from Anne Hathaway’s house

Tourists come by coach or car

to wander in the gardens and wonder at the bed

They never hear the footsteps, never see

a young man’s ghost turning down the road

to Anne Hathaway’s house

Local folks glance out their windows

all day long as footsteps trod

across the road that winds its way

through town and countryside

to Anne Hathaway’s house

Read more posts like "“Anne Hathaway’s House”" at The Showbear Family Circus.

Air Bubble

Nina Chari over at The Showbear Family Circus - Lancelot Schaubert's and Tara Schaubert's liberal arts circus. said ::

“Please roll up your shirt Mr…..Lange?” The doctor glanced at her clipboard for confirmation. As he rolled his sleeve, a sea of violent, racist imagery slapped her eyes. She recoiled but continued shakily. “Ok Mr. Lange, you’ll feel a pinch.” The inmate’s metal teeth smirked at her. His neck tattoos danced.

“Clearly you don’t follow our belief system.” He rasped amused. The doctor remained silent as she inserted the needle.

Anxiety swept through her since she saw his name on the roster. Her every cell dreaded being in the same room. The fiend targeted people for a superficial cause and could conceivably target her family. He was a man similar to the one who had already done so.

“It wouldn’t take much to give him an air embolism”, she thought. “Just one air bubble away from freedom.”

Her mom, a devout Hindu whose dicta was far more assertive than Hippocrates’, scolded her in her head. “You must not shun your dharma- your duty. You are a doctor. Treat him as you would a saint. No exceptions. The brave realize this.”

The doctor stood up with dignity. “I wish your destiny upon you. Good luck. Guard, I am done here.”

Read more posts like "Air Bubble" at The Showbear Family Circus.

July 7, 2020

Where the I sees nothing

Anjali Sarkar over at The Showbear Family Circus - Lancelot Schaubert's and Tara Schaubert's liberal arts circus. said ::

I tried my best, perhaps too hard, to draw the eye

inward and focus on the incremental eight

steps that Patanjali claims will leave me awed

and enlightened and in need of nothing else. Our

model was the turbaned guru up front, beneath the ceiling

fan, who Om-ed until hearts sank and curtains soared.

The skies were blue outside and the birds soared

to heights only possible in the enchanted tropics. Aye,

this foreigner sat on the temple floor sealing

the distance between steps one and eight

and hoping to be enlightened within the hour

or at least by this Himalayan scenery, be awed.

After a couple hours’ quiet introspection I found it odd

that the down cushion grazed my bottom like a sword

and the serpentine spine could not be coaxed, like our

guru’s, to stay straight, any more than the wandering eye

could be enticed to be still, or the mind be pinned on the eight

fold path, or the kundalini be cajoled to rise to the ceiling.

In the days that followed the sealing

of the merger, my friends thought it odd

that I drank a gallon of bourbon a day and ate

almost nothing; and when they found the liver sored

and cysted, they categorically insisted that I

take stock of my life and see the shrink for an hour.

I listened to my friends and honored our

pact to see the shrink and stare at the ceiling

lying back on his couch to probe into this I –

that’s crazy and driven but at the same time odd,

to consider that as the markets soared

and dipped, it could overlook what it ate.

I saw the doc, I watched what I ate

and exercised every day for an hour.

I lived every day on the edge of the sword

until the day that I cracked though the ceiling.

After delegating my tasks and assets, it’s odd

that an Indian travel brochure caught my eye.

I read on the eight limbs of yoga and that did the sealing –

within an hour I booked a flight ready to be awed

by the sword of Vedic wisdom and the mystery that is I.

Read more posts like "Where the I sees nothing" at The Showbear Family Circus.

July 6, 2020

Darker Light

Anthony Salandy over at The Showbear Family Circus - Lancelot Schaubert's and Tara Schaubert's liberal arts circus. said ::

In darker nights where all is silent

Sit lights far off in the distance

Which flicker and grow ever brighter

But just as distant still-

For in these darkened months

Are even darker lights

Which dot the scarcely un-clouded sky,

But out in the snowy fields

And from the thatched farm house

The lights still sit quietly in the distance,

Not humming or moving anymore

But now strictly static

In the darkened days of yule

Where the sun never rises beyond-

The thin horizon that exists

Just beyond the hoary fields

And past the shrouded home,

For on the horizon sit lights

Which demand to be seen

And yearn to be enjoyed

In the ever darker night of year’s end,

But as I fade in and out of my mind

I wonder if the lights off in the distance

Truly demand to be acknowledged-

Or maybe the lights were a calling

From deep inside my mind

Which demanded light to be brought

A darker light in which to permeate the night.

Read more posts like "Darker Light" at The Showbear Family Circus.

July 3, 2020

Wisconsin’s American Zoo (WAZoo) Invites you to pet the meese

kevin sterne over at The Showbear Family Circus - Lancelot Schaubert's and Tara Schaubert's liberal arts circus. said ::

1

Tuesday I get a call from Boss to come down to his temporary office at my earliest convenience. Which means immediately. Boss’s office is behind Meese Trecks. It’s called this because Boss says the plural of Moose is Meese. So that’s that.

The two Meese are finicky and prone to violence. By finicky I mean they shriek constantly and bull-rush the fences. Ever since they took out a Feeder, we’ve had to feed them on this sort of dragline. I’ve thought about putting muzzles on them but my Liaison in Handlers warned me that muzzled Meese is just the thing That Journalist at the Gazette would get off on. So, the Meese remain finicky and prone to violence.

When I get to Boss’s office Boss tells me to take a seat. He’s wearing an American flag as a cape and waving around a bottle of gin.

“Dark times are upon us Stedman,” he yells over the Meese. This is how he starts most conversations.

He tells me the books look bad. “We’re off by several million.” he says before taking a long pull of the gin. “And that’s not even with that dumbass Handler and dead Joy the Elephant.”

Joy was the star of our longest running attraction Joy to The Elephant that ran every two hours, 6 days per week for 18 years. We had to put her down when she stopped walking. I haven’t figured out a creative way to tell the Investors or the public, so we have a sign that says: “Sorry, Joy is Feeling Down Today. Check Back Tomorrow Please.”

“The last thing we need is The Protestors finding out.”

“I agree sir,” I say over the shrieking of the Meese.

“These Protestors are getting out of hand.”

“I agree sir.”

1.5

The protestors have been a thorn in our collective sides since the Beluga spill. They say we provided an inadequate environment for the Beluga while constructing the temporary tank. We we’re very by-the-book, at the start. We had the Beluga on an American Zoo Association-approved tarp. We had the Handlers doing shifts to hose it down—all within passing if we got audited.

But the Beluga was pregnant.

And Park Doctor was on sabbatical.

This complicated things.

Next day protestors showed up with laminated signs that read: “Cesareans Aren’t Nature’s Way.” And at three entrance gates they chanted “Zoos Breed for Greed.”

Picture our Ticket Attendants trying to upgrade a family of four with that going on. The Lock Ness Monster Exhibit is a hard sell as is.

The other day they were linking arms and blocking the front of the parking lot. Like these people have nothing better to do. We had cars backed up to the exit ramp.

Turns out they’re here for the long haul. Last week I watched a truck unload a dozen sub-zero camping tents, sleeping bags, and boxes of Power Bars. Head of Maintenance says they’ve started using our glossy park maps as kindling in their garbage can fires. Those things are not cheap to print. We encourage Patrons to return them to one of our yellow bins. Sometimes I’ll walk around after closing and pluck useable ones from the trash. I won’t stand for these Protestors using my maps as Firestarter.

2

Today Boss says: per the investors, The Protestors need to go or heads will roll. Considering that I got one in Art School, which already costs an arm and a leg, I cannot afford to have my head roll.

Boss leaves without warning to yell Shut up Shut up Shut up at the Meese. I wait for him while he does this.

“If I could feed those Protestors to these damn Meese I would.”

I tell Boss we might have to call the Lawyer for that one. I also tell him his phone is ringing.

It’s Esther from Admissions. She says the protestors are spray painting “Welcome to WA Zoo, the Midwest’s Third Largest Animal Prison” all over the parking lot.

“What do these people want from us?” Boss yells, “Because if it’s money, we don’t have it.

“We could ask them,” I say.

Boss says, why don’t you ask them?

2.5

I return to my office and tell Intern I need him to go talk to the Protestors. Intern is a yesman to the roots. You can’t put a price on his type of loyalty. Intern interns 40+ hours per week without monetary compensation in order to gain invaluable experience in a professional setting. Pigs would fly before I did something like that. Pigs would also fly before I covered two maternity leaves like Intern has.

I tell him to find out what they want and then give him the keys to the golf cart, which he’s excited about.

3

We’ve had issues with the Peacock of late, the issue being its recent tendency to squawk somewhat aggressively at a very specific racial demographic of male visitors. My Liaison in Handlers reckons it’s some sort of hormonal imbalance due to the change in Feed Supplier. I had Intern run a cost benefit analysis to determine if switching back to the more expensive Peacock Feed would positively impact the bottom line. It wouldn’t, so we’ve decided to monitor the situation. And hope it resolves itself.

And hope that Journalist at the Gazette isn’t drafting some Gonzo piece about our racist peafowl.

While monitoring the situation, I receive a personal call, which I take even though it violates my rule of no personal calls on the clock. It’s from my One in Art School. My One in Art School only calls when they need something. Go figure, this time it’s money.

From what I gather, My One in Art School has not been responsible with their stipend and can’t afford art supplies.

“Why can’t you get an internship to cover the cost of art supplies?” I ask.

“Dad,” they say with hesitation, “The Muse doesn’t work that way.”

I hear no complaints from Intern re: this Muse thing.

“Listen,” I say, “You need to tell this Muse who is Boss.”

“I promise I will try.”

It tickles me when they say that. All I ever ask of my One in Art School is that they put forth their best effort. But because I am—as The Ex says—“a push over with the wrong priorities,” I condone a one-time-only-no-exceptions use of the Emergency Credit Card.

Somewhere in Primate Canopy I catch that Journalist from the Gazette sashaying around the slanted berm. There are signs as clear as day asking patrons not to walk due to erosion and the chance someone might break an ankle and sue, which we’d definitely need our Lawyer for.

“You,” he says, “I need to talk to you.”

I re-stake the sign he’s knocked over.

“I need a story, man. The journalist prods me with the butt of his pen. “Something that will get clicks. Preferably something easy so I don’t have to pay out of pocket to come back here.”

I ask him if he’s talked to the Protestors. He says people protest everything these days and there’s no story there. I tell him our Welcome Wagon Menagerie could use some exposure.

The Journalist scribbles something on a receipt. He says readers want WOW factor and asks if we’ve had any animal-on-man crimes or accidents of late.

Our Lawyer has advised us not to talk about these after the gorilla reached through the fence and nearly choked a Patron by tie. We had to shoot the gorilla. Then we had to shoot it a second time because the first shot didn’t kill it. Now I have Intern wear a gorilla suit sometimes and just kind of lay around far enough away so people can’t tell it’s a suit. Boss thinks this might be the way of the future for the zoo business.

The Journalist says readers only want tragedy porn. “Pure spectacle,” he says, “But between you and me, man, I’m all for selling out for clicks.”

I can sympathize with this. I tell him I can respect a man who is willing to do what it takes to be a success. But then he goes into this diatribe about the death of print media and journalism ethics and his insurmountable credit debt. Blah, blah, blah. I got my own laundry list of problems. Has he thought about taking an internship in a career field that isn’t going the way of the Dodo?

“I’m just trying to survive,” he says.

“We’re all trying to survive,” I say.

4

Intern tells me he has big news re: The Protestors. Apparently one of them is refusing to eat until we release an animal. I relay to Boss.

Boss says this is just a stunt and we should let the Protestor starve.

I ask if that’s our official position if the Journalist asks.

Boss says this is just a cry for attention and we should give it time to play out.

So we give it time to play out.

5

Next morning I reassess things. The situation is as follows:

All 50+ protestors have taken a blood oath to go hungry until we release an animal into the wild.

The Journalist has written a puff piece concerning the hunger strike.

The Journalist also calls me for comment and I may have told him the Protestors are suspected terrorists and he might want to start looking at I.D.s. I learn this was not a good thing to say.

Boss says it’s not looking good for us. We’ve had three field trips cancel already and it’s only 10am. Field Trips are the only thing keeping our ship afloat.

Boss also says per the investors, heads are on the chopping block and assets are being liquidated.

So that’s where we are at.

“We need to stop footing around and take action,” Boss says, and asks if I know anyone who might stick their neck out for the greater good of the company.

“Preferably someone who needs us more than we need them,” he says.

I say I could go talk to Intern. Boss says why don’t I go talk to Intern? So I go talk to Intern.

6

I explain to Intern the situation and say we have zero budget. Intern is fully bought into wearing the gorilla costume and running/monkey-crawling across the parking lot.

6.5

I help Intern climb into the gorilla suit and then zip up the zipper on the back, which he is unable to do himself due to the undexterous rubber hands. When he’s all zipped up I kind of do that father-to-spawn-pep-talk-think where I lovingly push his shoulders back and tip his gorilla chin up so he’s looking confidently in front of him.

“You’ll do great.” Then I get slightly teary-eyed and Intern wipes at my cheek with his gorilla index finger but knocks my nose and not my cheek.

“Sorry.”

My One in Art School used to give this lean-in huggy thing around my waist back in here crayon construction paper days. And though I’ve never had a son, right now Intern might as well be.

Then Intern says, “I’m sweating profusely,” and that means it’s time to go.

7

There’s about a mile-long stretch of woods separating the back of the parking lot from the highway. Plan is for Intern to scamper across the parking lot, plunge into the forest, and then wait for me on the side of the highway to pick him up in my Ford Taurus.

Intern does make it successfully to the end of the parking lot. But he’s not fast enough in the heavy suit to elude the damn Protestors. The thirty or so of them encircle him at the edge of the woods and then close in like a pack of wolves. Poor Intern, trapped like a bunny rabbit, falls into a fetal ball.

8

Next day I show Boss the front page of the Gazette, which pictures Intern tied to a tent pole, stacks of our brochures at his feet. It’s 7am. Neither of us have slept. And Boss is has been drinking gin through the night.

“These hunger-striking Protestors are cannibals,” Boss tells me. Outside the Meese are ramming into the fences.

I tell Boss at least they have the human decency to let the suit drape at his waist.

Boss asks me what is our company position on negotiating the release of hostages from protestors?

“I don’t believe we have one,” I say, “But if we get him back alive, I can have Intern draft one.” Boss waves his hand at me, which I take to mean it doesn’t matter because we probably won’t make it to see another week at this zoo.

He asks me how much money I have in my bank account, which turns out to be $162 after the $4 service fee. Boss and I agree that time is of the essence and forgo copying the serial numbers in lieu of riding off in the golf cart to negotiate Intern’s safe release.

9

We slide into the parking lot to find the Protestors prancing around Intern, arms locked and chanting “Hey Ho, Let Those Animals Go” like battle cry.

This tattooed guy with blonde dreadlocks is kind of instigating everything with a bull horn.

I say “Happy day,” and ask Guy with Bullhorn if he’s in charge.

He tells me with the bullhorn that this is a free, non-violent assembly.

Boss pokes him in the chest with the wet end of his bottle of gin. “You’re ‘bout ready to burn our man at the stake,” he says, “You call that peaceful?”

“Peaceful is your word, man,” the Guy with Bullhorn says, “We said non-violent.”

Boss says to give Guy with Bullhorn the money, so I give Guy with Bullhorn the $162. Guy with Bullhorn looks at the money in my outstretched hand, then looks at me, then looks at his people, then looks back at me. He starts laughing. His comrades start laughing as well.

I can see that sweat has pooled under Intern’s neck. I imagine that everyone is frozen still except me, and like a hero I rip the rope binding Intern to the tent pole and carrying him off into the woods like a groom with his bride. Then Boss picks us up in his BMW and we drive off to Big Baby Boy Burger Bar.

I’m pulled from this fantasy by the violent flames Guy with Bullhorn has produced with his lighter and my wad of money.

“We don’t want money,” Guy with Bullhorn says.

“What do you mean you don’t want money?” Boss says, “What else is there?”

This starts a chant: “Free Those Animals. Free Those Animals.”

“Here’s how this is going to go,” he says while walking over to Intern and the stacks of brochures, “You let us go in and rescue all endangered, vulnerable, or threatened animals. We take them to Federally Protected Nature Preserves. And in exchange you get your guy back.”

“But we don’t have any endangered animals,” I say, “They’ve all died.”

“No Sea Lions?”

“Dead.”

“Hawksbill Turtle?”

“Dead.”

“Alaskan Moose?”

“We have Moose. We definitely have two Moose.”

“Meese,” Boss says waving the gin around.

I say you can have them. Guy with Bullhorn says they’ll take them. And Boss says they’re all yours.

10

We all march across the park to Meese Trecks. That is me, Boss, and the Protestors led by Guy with Bullhorn. Intern is no longer tied to the tent pole but is closely guarded by an enclave of Protestors.

Outside Meese Trecks the Meese are shrieking. Boss uses Guy with Bullhorn’s bullhorn to talk over the shrieking Meese.

Boss explains that the Meese need to be pet in order to be handled, and demonstrates by rubbing my belly. “But once they’ve been petted,” he says, “they’ll obey you like a dog. Then he gives Guy with Bullhorn his Bullhorn and opens the gate for the Protestors. The Protestors go inside single-file.

The Meese charge. The male knocks two protestors to the synthetic grass which is two parts carpet and one part pine needles. Very hard. I definitely hear something like bones crunching. We are surely done for. Bodies are splayed on the ground. Even with our Lawyer we won’t survive this.

Boss sets fire to a bottle of gin and chucks it at his office. The inside instantly bursts into flames.

Things escalate quickly.

The Meese chase most of the Protestors to the 20-foot perimeter fences. They have no way out, firewood waiting to burn. Some make it out safely, but many at the bottom are picked off. I’m no use to help them. My ears are ringing, my heart pounding, and I can’t seem to move my legs.

I find the Journalist with the video-end of his phone pointed at the male moose which is catapulting a Protestor into the fake pond. Blood pools. We kind of lock eyes and I try to tell him nonverbally that I now respect the hell out of his profession.

11

Intern and Boss pull up in the golf cart. “Mistakes were made,” Boss says, “We’re going to lay low at Big Baby Boy Burger Bar.” I start to get in and see the Protestors are jumping from the tops of the fence. Falling to their sure death.

Boss and Intern see this too. And then we look at each other. A memory of me and my dad in our back yard comes into my head. He’s standing over me and explaining the value of a dollar, new lawn mower at his side. I’m eight years old.

I’ve made many mistakes in my life.

I wipe a tear from Boss’s cheek. He’s the closest thing I have to a father right now.

“We are all going to hell,” he says.

“You’re right sir.”

And Intern, Intern is as solid as stone, driving us to our future.

Read more posts like "Wisconsin’s American Zoo (WAZoo) Invites you to pet the meese" at The Showbear Family Circus.

July 2, 2020

emma sywyj photography

Emma Sywyj over at The Showbear Family Circus - Lancelot Schaubert's and Tara Schaubert's liberal arts circus. said ::

[image error]

Read more posts like "emma sywyj photography" at The Showbear Family Circus.

Cookie Monster

Joe Tamel over at The Showbear Family Circus - Lancelot Schaubert's and Tara Schaubert's liberal arts circus. said ::

One of my first teaching assignments was in a middle school on the east side of Milwaukee, a place known to its natives as a bastion of quaint and kitschy restaurants and shops. To this day, some of my favorite places to visit and imbibe sundry types of brewed drinks are in that part of town. However, Milwaukee, like so many of America’s major cities, is also a highly segregated metropolis harboring impoverished neighborhoods, under-served people, and a deep, unremitting prejudice that challenges my long-since revoked belief that I would encounter increased racial strife the farther south that I moved.

I don’t acknowledge this casually. I think it’s imperative to establish that I was a 23-year-old white man working amidst an almost exclusively black school population. In addition, I was convinced that I wanted to work with high school students, not with 11-year-olds. To that point in my nascent career as an educator, I’d not exhibited patience either for rambunctious pre-adolescents or for jejune curricula. Back then I considered myself a member of the intelligentsia who wished to engage students at the peak of Bloom’s taxonomy. If I spent too many hours in a day anywhere near the bottom of that pyramid, toiling with rote memorization and fact recall, I would suffer irritable bowel syndrome. Obviously, I believed this school that contained grades 6-8 and posted security at its doors would fail to satisfy my aspirations.

I wasn’t prepared for what followed.

First, the mentor teacher to whom I was assigned was not far along in her own career. She was young and inexperienced for a “veteran” and had taken me on as a student-teacher without having yet completed the required training necessary to tutor one. Like many school systems, MPS was desperate to breathe fresh air into its culture via a youthful and energized teaching force, but it lacked the necessary human infrastructure to accommodate them. Therefore, similarly callow and inexperienced teachers were rallied to the cause and enrolled into the accreditation course so they could model their unrefined teaching skills for new cadets like me. It was your basic “babies-raising-babies” scenario which never turns out well.

So, I worked alongside a well-meaning mentor who was overwhelmed by her responsibilities before I arrived. Upon reflection, I’m not sure she was much more prepared to teach than I was. A victim of the self-perpetuating failed system she, too, would have benefitted from having a mentor work alongside her on everything from lesson planning to classroom management. Instead, the skills she modeled for me—now viewed from the vantage of hindsight—were a committed work ethic combined with some abysmal instructional habits. Most Monday mornings we spent as much time during our planning sessions rehashing the steps she’d taken to get blitzed with her friends the previous weekend as we did discussing the best way to teach students how to recognize a noun—a challenge made increasingly difficult when many of them struggled to even read.

Wait. This is somewhat misleading. She could fixate on her active weekend lifestyle but not because she eschewed or disregarded curriculum. Our chats concerning best practices related to the transmission of information and skills were hindered by the reality of our setting. Here, teaching was less about content or pedagogy than it was about stratagems for babysitting a mob. When a school district assigns 35 hormonally charged, starved-for-attention, and recalcitrant middle schoolers to your classroom, the ensuing cacophony is dizzying. I daily exited that building with a grinding headache and a budding appreciation for vows of silence.

What I learned about classroom management from my mentor was to meet the noise of the crowd with a greater noise of my own. Really. This was a tactic. Scream louder than they do. Oh…and threaten, often. This was how students heard and understood you; this was the lingua franca of middle school. Each forty-minute period consisted of shouting above the din of highly distracted, confrontational, and insolent children, continually redirecting their attention back to the chalkboard and away from random projectiles, breaking up fights (both verbal and physical), and answering the same question a dozen times. Putting together a seating chart was like solving the Rubik’s Cube only in this scenario the various colors and rotating squares were warring factions of students who were as likely to call each other a “nappy headed Mo-fo,” as they were to slap each other for “lookin’ at me funny.”

I broke up more fights than I collected assignments during those few months. Looking back, I’d like to say that while Language Arts fell by the wayside I provided the education for those kids that the situation demanded like how to resolve differences, how to treat others with a modicum of respect, how to exhibit self-control in a volatile situation, but I’m sure I failed in this task as well. Worse, I disregarded the small percentage of students who were motivated to learn amidst the fires I was putting out around them.

During this time, I met a boy who, for the purposes of this communique, I will call Drew. He was 11 years old with the crooked and discolored teeth of a Rugrats character and dark blotches that mottled his complexion near his left temple and along the jaw line. His equine neck looked incongruous on his slight shoulders, and his ears stuck out like suitcase handles. Drew wore the same striped t-shirt and filthy jeans every day and failed to practice suitable personal hygiene. While he was not alone in these habits, his diminutive size and his exasperating nature often made him the target of ridicule. One of the smallest boys in the 6th grade, he more than made up for his limited stature with his mouth and with his hands. He was vocal and touchy, an explosive combination especially when it came to girls. In short, he was a menace—the linchpin of the grenade that daily erupted in class.

We moved Drew’s seat assignment constantly. It didn’t matter which quadrant of the room we placed him, soon he would be under the skin of a nearby student or out of his desk challenging someone who’d “said sumpin’ nasty,” to him. It didn’t much matter where he started the class because Drew usually ended up in the hallway to await a conference with one of us, and when we’d finally get around to stepping out of the classroom to address his behavior, he’d be gone. Most of the time we didn’t have the energy to locate him. Everything was easier without him present. I learned to stop caring and left the responsibility of his whereabouts to the “real” teachers.

We never worried that Drew would disappear from school. It was much safer and more comfortable for him to wander around the hallways or to hang out in bathrooms or in the gymnasium or on the playground and mix it up with other kids. When he got bored, or caught by an administrator, he’d reappear in class to start the process all over again. I suspect that there were some teachers who cared, who chased him down and tried to hold him accountable, but the rumors I heard amongst the 6th grade teaching team divulged that Drew’s situation was like so many other kids in the school: his mom was a crack addict, his dad was persona non grata, and his grandma was doing the best she could just to get him onto a school bus every day. There was no one coming to an after-school meeting for this child. The incorrigible and relentless behaviors we daily witnessed were ten times worse in Grandma’s house than in our own “structured” environment and kicking Drew out of school was not an option considering his antics were relatively harmless to broader society as long he was contained in our space.

Drew was in my 1st period class which meant I saw him first thing every morning. Meanwhile, a few weeks into this teaching experience, it became apparent that our 3rd period class housed some of the most troublesome boys in the 6th grade. My mentor came up with an inspired plan: divide and conquer. If we could remove a handful of the worst dissidents from the class, we might get some work done with the rest of the children. My new job for 3rd period became that of a special education instructor. I was assigned six of the most inveterate students I’ve ever encountered in any single setting over my 20+ year career. I was given a small conference room with an eight-foot table in the middle of it, and there, with a half-dozen boys deeply committed to a future as thugs, I would attempt to teach the day’s lesson while my mentor worked with the other 28 children in the classroom. A week into the plan, she lauded the progress that she was making. A week into the plan, I was still trying to cover the first day’s material with my group.

That room, that daily interaction with those boys around that table, became a seminal moment in the formation of my educational philosophy. Hell, it became a seminal moment in my development as a human. Admittedly, I loathed the first couple of weeks. I resented what I assumed to be an abuse of my role as a student teacher. There was no evidence that the boys were learning anything since most of the time was spent addressing their conduct, showing them how to find the right page of the textbook that few of them ever brought, and re-establishing basic communication skills and concepts that were missing from their memory or from their experience. The boys turned the situation into a badge of dishonor. At first, they didn’t find my singular attention appealing; they wanted to know why they’d been quarantined, and they were far too street smart to be fooled into thinking that it was because they were “lucky” or “superior.” Their initial response was so corrosive that I began to record the sessions in case something might go terribly sideways. They relished the opportunity to perform when my tape recorder appeared on the center of the table. I was in way over my head.

My spouse, a dedicated new mother and a highly supportive partner, was also a brilliant elementary school teacher. She would listen to my complaints over dinner, validate my frustration, and then quickly offer advice on new ways to approach this challenge. Far more accustomed to the antics of highly energized and belligerent children, she daily provided new strategies to employ and, over time, some of these efforts began to work. Her best piece of advice was that there would be no respect without a relationship. After about four weeks, we started to make some headway—these scalawags and me. There were days—granted, very few of them—where I exited that room believing we’d taken a positive step towards learning something. More importantly, though, I was evolving. I found myself laughing with the boys; I was slower to take offense when they cussed or at their puerile banter. I relaxed on challenging every excuse they offered. I started appreciating their unique “take” on a world about which I knew very little rather than assuming they were ignorant. Fundamentally, there were moments when our roles switched and they would determine the day’s lesson while I learned something new.

Meanwhile, my interactions with this band of malcontents began to affect my interactions with Drew. The training that I was getting in that room, which sometimes felt like an emotional pummeling, was softening my stance on our most egregious perpetrator of classroom terrorism in 1st period.

Allow me to take you back to a moment very early in my experience to provide context.

Not long after I began working at this school, I was on lunch duty when a fight broke out. The cafeteria was situated two floors above the 6th grade classrooms and on the same floor where the 8th grade students were contained. During a class change that corresponded with our lunch hour, a mêlée broke out amongst a few of the oldest students in the school. Fights of this nature always draw a crowd, and students are often aware of the simmering squabble long before the teachers. By the time the first shove commenced, an audience of 8th graders had gathered to watch, and a few spectators had gotten in on the action. The brawl spilled into a stairwell, greatly increasing the danger of the situation due to the narrow and elevated terrain. With security personnel and teachers scrambling to stem the tide, opportunity arose for our 6th graders. The teachers’ attention fixed upon the ruckus meant some of our own students could bypass our normal procedures for leaving the cafeteria. The ensuing chaos coupled with the passing of time hinders the accuracy of my recollection. What I do remember quite vividly, however, is standing in the hall instructing 6th graders to stay in the cafeteria downwind of the fight and then seeing in my peripheral, Drew, sprinting towards the scuffle with an expression on his face that could only be defined as gleeful. This was a bee-to-honey-pot situation if ever there was one and quelling the riot would become a far more difficult proposition if Drew showed up on the scene. That kid could instigate Ghandi to a fist fight. I moved without thinking. I lunged forward and intercepted Drew and, due to the size and weight differential, harnessed him with one arm around his neck even as he attempted to side-step my intervention. He was so light and so small. I effortlessly spun him around to face me and in one motion placed both of my hands into the armpits of his dirty shirt. Grabbing the extra material that hung off his undernourished skeleton, I lifted him off the ground and pushed his back against the lockers so I could pin him there face-to-face. Drew was in a state of shock. This was likely not the first time an adult had laid hands on him, but it was likely the first time a teacher had.

He stuttered a complaint. It may have been the first and only time in his life that he was unable to deliver a clever quip under duress. Up to that point all my interactions with him had been verbal redirection that would usually devolve into an argument. He relished puffing his chest before calling me names and accusing me of taking another student’s side. This time, however, he was scared and mute.

Taking advantage of our proximity, I leaned in close and whispered, “You had better get back into that cafeteria or else…” Drew’s eyes got big. I set him back down, and he hightailed it back towards his peers, looking back to make some wise crack. He needed to save face in front of the audience of students who’d witnessed our altercation, but I didn’t register his insult. I was physically shaking. I looked around to see if any other teachers had seen what I’d done, but every adult’s attention was on the stairwell or intent on herding students back into the cafeteria. I took numerous deep breaths to settle my nerves. I’d almost ended my career before it had begun because I’d manhandled a 6th grader who was acting pretty much how he’d been programmed.

Now, almost two months after that encounter, thanks to this small group of 3rd period boys my edges were filed, my fuse was lengthened, and my disdain for my role had been tempered and replaced with a growing sense of concern for these children whose bravado and tough exterior belied their fear and insecurity. The more time I spent with them, the more I recognized how essential grace, promise, and opportunity that is proffered to so many others was lacking from their lives. I learned to accept them. I grant that I wanted to see them change in some important ways, but I no longer viewed these students as problems to overcome or discard. I made a radical tactical change. I would no longer consider these kids antagonists; they were my charges, my pupils. A combative relationship in education only ever ends in failure for both parties.

Additionally, I focused my attention on those few students I’d previously overlooked, those kids who in the face of all this difficulty and all this distraction—surrounded by neglect, abuse, poverty, and deep-seated social illnesses—had found a way to succeed. To watch these 6th graders push past their ill-fated destiny and write beautifully constructed journal entries, to observe them analyzing the poetry of Dickenson and Cummings, to see them momentarily swept into an alternate reality by Bradbury and Asimov was a revelation. It made me question why I’d treated Drew any differently than these children who were flourishing in my classroom. This new consciousness gave me permission, nay, required that I change my stance towards him. I would whisper to get above his volume. I would welcome him with a smile in the doorway rather than warn him with a glare as he entered. I would take a deep ataractic breath whenever he began to venture off the rails rather than loudly exhale my resentment. I would first ask him to consider and adjust his behavior rather than order it of him.

I would reach out and lightly touch his shoulder to remind him I was nearby rather than hoist him against the wall by the front of his shirt.

Alas, where Drew is concerned, I wish I’d achieved this enlightenment earlier. Eventually, he pushed too many buttons in his other classes and mere weeks after I installed my new approach to working with him, he was placed into a program that operated much like an in-school suspension. My final days at the school would not include him in my class. In truth, I’d resigned myself to the inevitability of this outcome. Like so many people who eventually end up incarcerated for periods of time, Drew appeared destined for significant portions of time spent in isolation for the benefit of others. As my assignment at the school concluded, I lost touch with him.

I never got the opportunity to say goodbye to Drew, but this fact did not prevent him from teaching me a final and, perhaps, most meaningful lesson. On my last day teaching at that school, we held Christmas parties in our classrooms. Holiday music played in the background, students adorned themselves in green and red, teachers sported Santa hats, and candy canes decorated every desk. A few of the students fashioned homemade cards for us; some brought small gifts. I was cleaning out my desk when my mentor approached me with something in her hands. Her countenance was diametrically pensive and excited as she placed what appeared to be a pile of napkins on my desk. Upon closer examination, the offering revealed itself to be a wad of unused Kleenex.

“It’s from Drew,” she said.

I stared at the malformed ball of Kleenex wrapping paper for a moment, unsure what to make of it.

“One of the administrators dropped it off. It’s for you.”

That Drew was not allowed to attend the Christmas party was not a surprise. Placing that boy into such an environment would be like placing a hyper-sensory cat in a room with an operational disco ball. What was astonishing was realizing he’d sent a gift.

Becoming fully aware of the gravity of the moment, I preferred to be left alone to open the present, but my mentor, as captivated and awestruck as I was, crept closer. I reached down and began to slowly and carefully unwind the “wrapping.” Piece by piece the tattered tissues fell onto the desk. The package, already quite delicate, became trifling and began to separate as the bandage unraveled. When I finally reached the last sheet of tissue, I opened my hand, palm up, to reveal Drew’s gift. Sitting atop that final shard of Kleenex were three gingerbread windmills. If you’ve never seen the type, windmills are shortbread cookies with chopped almonds imbedded into the mixture, and they are shaped like old-timey Dutch…windmills.

I sat there speechless. My mentor, too, lacked any expression other than a strange noise. You know the sound. It’s that wheeze that escapes when there’s a stoppage of breath midway between deep inhalation. It is a tell, always, of an unexpected emotional reaction. I looked up. Her carefully manicured eyes, darkly lined by mascara as they always were, glistened softly with the reflection of light held in droplets of water.

“Joe…”

I stared at this tough-as-nails, party-girl extraordinaire (from what I could deduce from our Monday morning meetings anyway) and couldn’t believe what I was seeing. This no-nonsense young woman who took no gruff from crowds of rabid middle-schoolers was beginning to choke up and cry. The Kleenex on my desk returned to its natural use.

Me? I’m the guy who sets down on the curb immediately after witnessing a horrific accident and proves useless to potential survivors as he curls up into a ball. I just sat there like an idiot trying to process the situation.

Then, feeling compelled, I guess, to explain her reaction my mentor said, “What a beautiful gift. I bet that’s everything he has.”

I can appreciate that she wanted to be sure I understood the magnanimity of the moment, but the fact is this was not my first rodeo. When I was just a youngster, I had a friend, Derek, who gave me a gift that was obviously one of his own matchbox cars. While other kids passed me perfectly wrapped boxes of brand new and in some cases expensive toys that their parents had purchased for them to bring, Derek produced from the pocket of his jeans without fanfare or wrapping paper a slightly scratched and dinged orange Mustang—the very car I’d complimented just weeks before as my favorite among his collection. At the time he’d beamed proudly and acknowledged that it was his favorite too. Yet, on my 5th birthday he gave it to me.

That chipped and rusted orange Mustang was the best gift anyone had ever given me until a little monster gave me a trio of windmill cookies wrapped in Kleenex for Christmas.

I walked away from that experience a transformed educator because of what a half-dozen malefactors-turned-mentors taught me about adversity, about perspective, and about tolerance for others whose life experience is wholly different from your own.

And I walked out a better human because I’d met a kid named Drew.

Read more posts like "Cookie Monster" at The Showbear Family Circus.

July 1, 2020

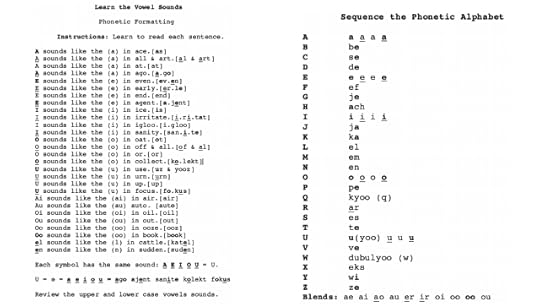

Reading and Decoding English

Dennis Brooks over at The Showbear Family Circus - Lancelot Schaubert's and Tara Schaubert's liberal arts circus. said ::

Reading and Decoding English 7

Letter

2.2 Self-Educated

If you know people who have Dyslexia, help them learn to

read starting with this column. It takes patiences to teach them the individual

sounds.

This is an excerpt from Title: Frankenstein or The Modern Prometheus by Mary Wollstonecraft (Godwin) Shelley

Hou wood such a frend repair the faults ov yo por brother! I am too ardent in eksekooshon and too impashent ov difikultez. But it iz a still grater evil too me that I am self-ejukated: for the first forten yearz ov mi lif I ran wild on a kommon and red nothing but our Unkel Thomas’ books ov voiejez. At that aj I bekam akwanted with the selebrated poets ov our on kuntre; but it waz onle hwen it had sesd too be in mi pouer too deriv its most important benefits from such a konvikshon that I persevd the nesessite ov bekoming akwanted with mor langwejez than that ov mi nativ kuntre. Nou I am twente–at and am in realite mor illiterat than mene skoolboiz ov fiften. It iz troo that I hav thout mor and that mi dadremz ar mor ekstended and magnifisent, but tha want (az the panters kal it) keping; and I gratle ned a frend hoo wood hav sens enuf not too despiz me az romantik, and afekshon enuf for me too endevur too regulat mi mind.

Letter

2.2 Self-Educated

How would such a friend repair the faults of your poor brother! I am too ardent in execution and too impatient of difficulties. But it is a still greater evil to me that I am self-educated: for the first fourteen years of my life I ran wild on a common and read nothing but our Uncle Thomas’ books of voyages. At that age I became acquainted with the celebrated poets of our own country; but it was only when it had ceased to be in my power to derive its most important benefits from such a conviction that I perceived the necessity of becoming acquainted with more languages than that of my native country. Now I am twenty-eight and am in reality more illiterate than many schoolboys of fifteen. It is true that I have thought more and that my daydreams are more extended and magnificent, but they want (as the painters call it) keeping; and I greatly need a friend who would have sense enough not to despise me as romantic, and affection enough for me to endeavour to regulate my mind.

FEATURED DOWNLOAD: If you would like an infographic on how to read books and watch films more reflectively, CLICK HERE.

Read more posts like "Reading and Decoding English" at The Showbear Family Circus.