Lancelot Schaubert's Blog, page 81

September 1, 2020

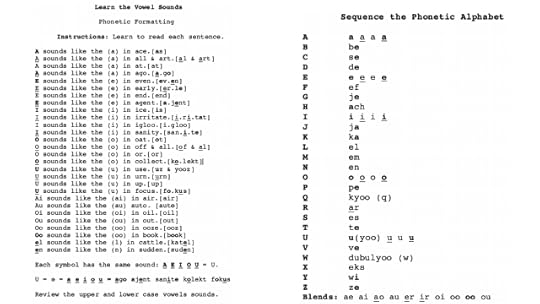

Reading and Decoding English

Dennis Brooks over at The Showbear Family Circus - Lancelot Schaubert's and Tara Schaubert's liberal arts circus. said ::

Reading and Decoding English 9

Letter

2.4 My Generous Friend

If you know people who have Dyslexia, help them learn to

read starting with this column. It takes patiences to teach them the individual

sounds.

This is an excerpt from Title: Frankenstein or The Modern Prometheus by Mary Wollstonecraft (Godwin) Shelley

I herd ov him first in rather a romantik maner, from a lade hoo oz too him the hapines ov her lif. This, brefle, iz hiz store. Som yearz ago he lovd a yung Russan lade ov moderat forchun, and having amasd a konsiderabel sum in priz-mone, the father ov the girl konsented too the mach. He saw hiz mistres wons befor the destind seremone; but she waz bathd in tearz, and throwing herself at hiz fet, entreted him too spar her, konfesing at the sam tim that she lovd another, but that he waz poor, and that her father wood never konsent too the yoonyon. Mi jenerus frend reashurd the supliant, and on being informd ov the nam ov her lover, instantle abandond hiz pursoot. He had alrede bout a farm with hiz mone, on hwich he had dezind too pas the remander ov hiz lif; but he bestod the hol on hiz rival, toogether with the remanz ov hiz priz-mone too purchas stok, and then himself solisited the yung woman’z father too konsent too her marij with her lover. But the old man desidedle refuzd, thinking himself bound in onur too mi frend, hoo, hwen he found the father inekzorabel, kwit hiz kuntre, nor returnd until he herd that hiz former mistres waz marid akording too her inklinashonz. “Hwat a nobel fello!” yoo wil eksklam.

Letter

2.4 My Generous Friend

I heard of him first in rather a romantic manner, from a lady who owes to him the happiness of her life. This, briefly, is his story. Some years ago he loved a young Russian lady of moderate fortune, and having amassed a considerable sum in prize-money, the father of the girl consented to the match. He saw his mistress once before the destined ceremony; but she was bathed in tears, and throwing herself at his feet, entreated him to spare her, confessing at the same time that she loved another, but that he was poor, and that her father would never consent to the union. My generous friend reassured the suppliant, and on being informed of the name of her lover, instantly abandoned his pursuit. He had already bought a farm with his money, on which he had designed to pass the remainder of his life; but he bestowed the whole on his rival, together with the remains of his prize-money to purchase stock, and then himself solicited the young woman’s father to consent to her marriage with her lover. But the old man decidedly refused, thinking himself bound in honour to my friend, who, when he found the father inexorable, quitted his country, nor returned until he heard that his former mistress was married according to her inclinations. “What a noble fellow!” you will exclaim.

Featured Download: CLICK HERE to unlock the methods for preparing your life for creative inspiration and visionary change.

Read more posts like "Reading and Decoding English" at The Showbear Family Circus.

August 26, 2020

George MacDonald against Hans Urs von Balthasar on Universal Salvation

Jordan Daniel Wood over at The Showbear Family Circus - Lancelot Schaubert's and Tara Schaubert's liberal arts circus. said ::

Many a wrong, and its curing song;

Many a road, and many an inn;

Room to roam, but only one home

For all the world to win.

(Eve, in MacDonald’s Lilith)

I want to put two eschatologies in conversation, that of Hans Urs von Balthasar and that of George MacDonald. The former, because I consider his the most interesting and potent eschatology on offer in modern Catholic theology. His defense of a “hopeful universalism,” which does not claim to know that all will be saved but insists it’s a Christian duty to hope that all will, has become fairly popular in many quarters. Not all, of course; not for the Thomists or the Neo-Augustinians or even, sadly, many contemporary Orthodox theologians. A keen sense of “the dramatic” in God’s dealings with humanity throughout history along with an ostensibly modest claim to epistemic humility about matters eschatological—this is the near irresistible concoction the great von Balthasar offers as antidote to the poison Augustine has injected into most of the Western tradition.

An essential though far less treated feature of von Balthasar’s polemic is his self-distancing from and criticisms of the certainty assumed not just in Augustine, but also in Origen’s view of universal salvation. I’ll consider two of his preferred allegations:

[1] That the dramatic character of creation’s history demands that both divine and human freedom undermine any surety about final resolutions;

[2] That the theological virtue of hope properly precludes any presumption of eschatological certainty.

I summon George MacDonald to respond to and meet von Balthasar’s criticisms. MacDonald was at once a staunch Christian universalist (though he never claims the label)—a position carefully hewn from the hard ore of Scottish Presbyterian Calvinism—and a renowned dramatist: one of the pioneers of the fantasy genre in modern literature, author of numerous short stories and fairytales and novels, and frequent lecturer in theology, poetry, and other miscellany. He was also an avid preacher. I make no pretensions here: I will not simply detail each’s eschatology. I intend to use MacDonald against von Balthasar. As such my description of the former will conform to my criticism of the latter.

Von Balthasar

Some of Christ’s parables, a few of St. Paul’s statements, and certainly St. John’s Apocalypse all indulge the same images for God’s judgment of evil as are commonly found in the Old Testament; harsher, in fact. Von Balthasar warns that this can mislead. Under the common veneer lies a deep and significant shift: in the Old Testament God judges, in the New it is precisely Jesus the Crucified and Risen Lord who will judge the world (Acts 3, 17; Rev. 1, 5, 19, 20). Before Christ divine righteousness stood “behind” the judgment of reward and punishment. Now it is realized in the very person of Christ the Judge: divine justice is “in the judgment,” not behind it. Christ is “the Covenant personified,” party to no single side but the fulfillment of the whole by His oneness with both parties, God and humanity. More, the Son’s obedience to death, His becoming sin itself, and especially His descent into Hell have made of every distance forged by human rebellion a distance still infinitely more proximate than that of Son’s godforsakeness in dereliction. Christ’s radical kenosis even to the depths of the pit has brought the great cleft wrought by the wicked into the heart of the trinitarian relations—particularly the total self-giving between Father and Son—so that no sinner can wander where the Son is not. Von Speyr says: “even when a sinner turns to run from the Father, he will only run into the Son.” Christ’s cross and descent have made of every prodigal child God’s neighbor. Hence von Balthasar insists that while God’s judgment appears “symmetrical” in the ancient covenant, it is “asymmetrical” in the New with an evident penchant toward grace, salvation, restoration. Even so, von Balthasar refuses, from Theodrama V to his final writings, to brave the more confident claim that all indeed will be saved. Here I sketch his main reasons for hesitancy.

1. The mystery of freedom.

In the Theodrama, von Balthasar’s principal approach to this question is, perhaps unsurprisingly, to locate it in the context of the dramatic interplay between God and humanity. These are the primary actors because both enjoy freedom and agency. In the second volume von Balthasar defines human freedom in fairly unremarkable terms: there are two pillars which constitute it: the autonomy of self-motion and the “freedom to consent.” Both elements are (mostly) classical. The first amounts to the simple observation that rational beings are self-moved, that is, are reduced to neither mechanical nor merely organic processes for the “mental events” that lead to action; they really can call their acts theirs. They act out of no obligation and only of their own election. The second provides the “teleological valence” of human freedom: the very power to act from oneself comes from a still greater power with still greater freedom, the infinite freedom of the Creator. As such human freedom is also oriented or tends toward its source as ultimate end. It’s not pure libertine freedom, which, von Balthasar notes, is what separates it from many modern accounts of liberty.

So we have two actors in the drama of created being, divine and human (demons and angels also play important roles, but I leave them aside for now). The dénouement, as with the play itself, consists in the tangled and at times impenetrable actions of bothactors. There is no easy or guaranteed resolution in a good drama. This is what, incidentally, makes Christian history and eschatology something resistant to Hegelian “epic,” where, supposedly, the Absolute Spirit will eventually accomplish the pre-disclosed goal of history, willattain, that’s to say, its total self-realization in the whole of what is. The Spirit’s self-consciousness is present in history not only as the terrible engine of its progressive march, but as the inevitable goal of all human science and striving. True, von Balthasar does not make explicit mention of Hegel in the relevant texts here. But so much of his language is haunted by the latter’s specter. We’ll see how especially in the next section.

For now I note only that even the End must come about as the conjoined actions of both actors, and that this seems a radical rebuff of any sort of Hegelian resolution posited beforehand as the inevitable goal. And so von Balthasar constructs, as it were, two sorts of “theory” concerning universal salvation. First he delimits what he thinks we can say with certitude; then he offers something like a “hypothetical approach,” at least in Theodrama V. The first part details what we can say of the two agents’ action. “Man judges himself,” says von Balthasar. He means much the same as what C.S. Lewis meant about locking the door from the inside: God casts no one into the Lake of Fire against her will. Each person has the “capacity” to so cauterize her own heart, so despoil her soul of love, that she might will her own persistent and torturous separation from the sole source of her life, love, and bliss. Von Balthasar speaks of “The Serious Possibility of Rejection,” which, in the gloomy abyss of the human person, might indeed come to pass. Then there’s God’s final act as the judge of such persons—always the final action. He will certainly spare no means to save such a person since the one who judges is the very one who came to save. But again, in the face of that black hole called the human heart—which God created, recall—God himself might fail to bring that heart to rest in Him. Apparently the index of a decidedly anti-epic view of history is the real potential of final tragedy: “This possibility once again raises the idea of a tragedy, not only for man, but also for God himself” (TD V, p. 299).

Personhood resists all calculation. The final judgment of persons therefore resists all speculation, all systems, all confident or absolute verdicts doled out prematurely. We must then “proceed by way of hypothesis,” von Balthasar cautions. He does so in four points. First, he registers doubt that human freedom has the capacity after all to reject God finally or permanently. This is because the person who demands, in her autonomous self-motion, to be utterly independent and cut off from God can only do so in a perpetual state of formal contradiction, since the freedom by which she requisites total freedom must itself be exercised precisely in a state of being given to her. You can’t logically atomize yourself without depending on God in the very act of “autonomous” rebellion. Put otherwise, human nature is irreducibly dependent and so can’t act in freedom without God (indeed, von Balthasar further specifies that this “nature” actually bears the indelible mark of Christ’s own eternal relation to the Father, which makes a finer point here). Second, the timelessness Christ experienced in His descent to Hell far exceeds any “timelessness” of Hell itself. The sinner’s atemporal state is the very state of self-elected separation, and it expresses only that rebellion. Christ’s pure obedience to the Father unto cross and descent is actually an expression of His own eternal and immanent mode of possessing divine being; it enjoys all the infinity of divinity itself rather than just the near-indeterminate “nothingness” of hardened hatred. Third, this excess of Christ’s obedience is what allows Him to “accompany” any and every sinner to whatever depths of depravity into which they plunge. Here we have “the ineluctable presence of Another,” which is the condition of the possibility of anyone’s eventual repentance. Fourth and last, all this grounds the real Christian duty to hope for the salvation of all. Hope, as we’ll see presently, is not the presumptuous certitude of either Augustine or Origen, but is most properly the “blind hope” of St. Thérèse de Lisieux (though, it must be admitted that Thérèse’s expressions, especially in Récréations pieuses, blind or not, are hardly lacking in absolute confidence that “every soul will find forgiveness”).

2. Hope against certainty.

I discern a clear shift—not so much in logical content as in polemical form—between TD V (1983) and Dare We Hope ‘That All Men be Saved’? (1986), A Short Discourse on Hell (1987), and “Apokatastasis: Universal Reconciliation” (1988). If in the Theodrama von Balthasar emphasized the final indeterminacy of human freedom, now he wishes to brandish God’s absolute prerogative to exercise free and final judgment. From 1986 onward this becomes the refrain: “we stand under judgment,” we’re not spectators to the Final Act of this judgment. So a new charge, or at least a new urgency of an old charge, emerges: the charge of double presumption. Von Balthasar argues that Origen and Augustine share a common presumption. Both had the audacity to presume to know the final outcome, though, of course, each elected opposite certainties—but certainties nonetheless. Behold von Balthasar’s great and shrewd polemic: everyone who disagrees with him are “knowers,” from Origen to Augustine to Aquinas to Bonaventure to von Balthasar’s own right-wing critics. Only he and his like practice and properly maintain the theological virtue of hope. This obviously courts enormous rhetorical power. It amounts to saying that whoever claims to know whether anyone is in Hell—an affirmation conspicuously absent in magisterial teaching—is not only wrong but sinful, since such a claim betrays the vice of presumption. Hope opposes such illicit certainty, and “hope” happens to name von Balthasar’s view.

So now we find at least two reasons you must not claim to know whether all will be saved. For one thing, such certainty evacuates human freedom of meaning. If I know that no matter what I do, I’ll still end up at the same destination, how can my particular choices bear ultimate significance? If the final word of my own existence falls not to me, then do any of my words matter? The realization of every personal destiny is as impenetrable to the intellect as a person is to herself. This much already surfaced in Theodrama, and it’s still operative here. But, second, the principal problem with eschatological certainty is that it dares too much. Such audacity undermines the other great factor in the Final Act—that Christ alone gives the last word. Once again this is a fundamentally anti-Hegelian affirmation. Christ the Logos does indeed stand at the ultimate precipice of history, but not as some discernible principle realized at last. He stands as a free actor, the free Actor, whose judgment is his alone to deliver. Because He is the slain lamb (Rev 5) we can certainly “have confidence” (1 Jn 4.17). But we cannot have certainty. A proper hope repels the presumption of every certitude. This is the one merit von Balthasar can credit to Augustine: at least his presumption was a pastoral attempt to curb the “presumptuous hope” of other Church Fathers such as Origen and Gregory of Nyssa and other misericordes. These apparently succumbed to the temptation of constructing great “syntheses” and engaged in illicit “system-building” at the expense of genuine hope. “We stand completely under judgment and have no right, nor is it possible for us, to peer in advance at the Judge’s cards. How can anyone equate hoping with knowing? I hope that my friend will recover from his serious illness—do I therefore know this?” (Dare We Hope, p.131).

There lurks in fact a corollary reason why no one can know the final outcome. Near the end of Dare We Hope, von Balthasar admits that what comes along with the divine prerogative to judge, what makes it still more impossible to know the verdict here and now, is that God does have the power, after all, to save all. The grace that flows from the Son’s self-sacrifice into the world (2 Cor 5.19) could “grow powerful enough to become his ‘efficacious’ grace for all sinners.” “But,” he quickly adds, “this is something for which we can only hope” (Dare We Hope, p.167). He agrees with St. Edith Stein that God can indeed “outwit” even the very worst antics of human freedom, and that there are “no limits” to how far He can descend into the human heart. We’re just to be positively unsure as to whether He’ll really take the trouble.

Von Balthasar’s last writing, to my knowledge, was a talk he gave in 1988 on “Apokatastasis.” In it he takes his familiar line. Now, though, he appears even more sure about scripture’s indeterminacy on the question, alleging that anyone who claims eschatological certainty takes neither scripture nor faith seriously. Alas, “we must resign ourselves” to the possibility of ultimate tragedy, “our feelings of revulsion notwithstanding.” He calls his position of hope “the existential posture,” that is, the only perspective capable of holding in tension the ambiguities not just of scripture but of this our wrecked existence. He places himself between Paul, who says, “It is the Lord who judges me. Therefore do not pronounce judgment before the time, before the Lord comes, who will bring to light the things now hidden in darkness” (1 Cor 4:3-5), and John, who assures that “we may have confidence on the day of judgment” (1 Jn 4.17). Here below we live between fear and hope, though we must somehow gather ourselves to hope with daring. No certainty: an affirmation of any possibility, yes, but hopeful all the same. It’s our duty to hope for all to be saved; we know not whether He will deliver.

MacDonald

For MacDonald we certainly do know. Now his is no easy universalism. He neither evacuates meaning from the drama of human existence nor wavers about creation’s final outcome. This alone ought to give the Balthasarian pause, since, along with Dostoevsky, MacDonald was himself a universalist and a dramatist. He’s likely to know the stuff of the dramatic. And he’s just as likely to know what he rejects when he defects from Scottish Calvinism: “From every portrait of the God of Jonathan Edwards, however faded by time, softened by whatever less stark pigments, I turn away with loathing” (Unspoken Sermons, “Justice”). In the same sermon: “I know the root of all that can be said on the subject; the notion is imbedded in the gray matter of my Scotch brains; and if I reject it, I know what I reject.” In this work (and elsewhere) MacDonald articulates his own eschatological view: “God is not bound to punish sin; He is bound to destroy it.” He goes on to say that were God not the creator, perhaps He wouldn’t be so bound. But since He is, and since He made creatures who introduced the sin which devastated the world, and since, therefore, sin is at least indirectly the result of God’s own free creation, then He is, “in His own righteousness, bound to destroy sin.” The Son of God was revealed to destroy the works of the Devil (1 Jn 3.8), not simply to make sinners suffer for their sin. Such suffering, however many ages it endure, would never fundamentally rectify the offense of sin itself. Sin only suffers true defeat, MacDonald’s Adam-character tells Mr. Vane in Lilith, “when good is where evil was.” Anything less is not yet the “slaying of evil” that God, by the very act of creating anything at all, has obliged Himself to execute. I here note two striking features of MacDonald’s sure universalism. Each addresses von Balthasar’s objections.

1. The mystery of judgment.

MacDonald agrees with von Balthasar that the very character of personhood resists any generic account of how a person will arrive at her final destiny. Nearly all of his fairytales contain three main actors: typically at least two wayfarers in and out of Fairy Land, often children, and one “divine” guide who is also a sort of pedagogue or judge, often an “old wise woman.” The plot’s essential animus, its “dramatic” dynamism, is not so much an indeterminacy of the end as it is that of the way to the end (indeed sometimes the end of a character is not only presaged but openly predicted). What imbues the characters with the full latitude of dramatic possibility is not that they may or may not arrive at a reconciling end; it’s rather how they will manage to reach the end which is totally individual, totally personal, totally resistant to any generic synthesis or account. In his early novel, Phantastes, MacDonald’s protagonist is called “Anodos,” which, as those familiar with Greek will perceive, means “without a way.” The entire fantasy genre seems especially fit to display the point: Fairy Land overlays the “real” world, though it is itself more vivid and more real than anything in our own phenomenal “world.” It is only properly perceived and entered upon by those who are such as to be able to perceive and enter it. Ins and outs, byways and inroads and exits are all alike as individual as each person concerned. This often frustrates the main characters. They come and go they know not how, and when they inquire of their divine guide to show them the way, the guide usually says what Mr. Raven (Adam) says to Mr. Vane in Lilith: “To go back, you must go through yourself, and that way no man can show another.”

The mystery of personhood does not, however, finally subsume the mystery of God’s own judgment as it threatens to do in von Balthasar. This judgment, it needs to be said over and over, is notsome easy resolution or blithe acquittal. As MacDonald says in his sermon, “The Consuming Fire,” it’s precisely because God’s judgment must destroyevery trace of sin and evil in every soul that it promises to be indescribably painful. “Escape is hopeless. For Love is inexorable.” Again, in “Justice”: “A man might flatter, or bribe, or coax a tyrant; but there is no refuge from the love of God; that love will, for very love, insist upon the uttermost farthing.”

Nothing within Dante’s infernal circles can approach the horror of the judgment scene of Lilith, the Queen of Hell in that novel. Lilith is said to have been Adam’s first wife (as some actual but obscure Jewish lore has it). She bore him a child but soon grew weary of carrying out the will of her creator, and became quite enraptured by the power she experienced in having a child of her own. Envy and pride incited her to leave Adam and become a tyrant-queen over all the lesser creatures of Fairy Land, killing and terrorizing thousands for many, many ages. A prophecy was propagated alongside her reign that she would one day fall to her own child, whom she had abandoned for power. At length, through various wiles and ways, the protagonist, Mr. Vane, comes to lead an ebullient group of forest children called “The Little Ones”—the head of which, no one knew, was Lilith’s daughter Lona—into battle against the oppressive Queen Lilith. At the decisive moment when Lona learns that Lilith is actually her mother, Lona tries to appeal to her by familial love. Lilith slays Lona in cold blood. Soon after, Lilith is captured and brought to the House of Adam and Eve. There her judgment commences.

The whole masterful scene never fully turns on whether or not Lilith will ultimately be saved. We’ve already been told she eventually will be. What seizes the reader is the intensity of the judgment itself, its inscrutable and indescribable nature. Lilith sits before Mara, daughter of Eve, who conducts the judgment, as it were. The Little Ones ask whether it must be painful. Mara says indeed it must, and that it would be “cruel” if it were not painful enough; for it would then have to be done all over, and would be much worse. Two features of the scene are palpable.

First, the inflexibly individual or personal character of the judgment. So much of it is horrifying not because of what is described but because of what is not described, or what is not able to be described. The “process of torture,” as MacDonald puts it in one sermon, is essentially a process of coming to know the true self that you, through your ignorant rebellion, have never known, and then to compare God’s idea of you with what you’ve made of yourself. We do meet some descriptions: Lilith’s eyes are closed, sweat pouring off her brow; at one moment a “worm-thing” slithers out of the fireplace, “white-hot, as incandescent as silver,” and penetrates Lilith’s bosom in order to separate by excruciating fire, we’re told, bone from marrow and even deeper subtleties of the soul from one another. There’s very little else. Lilith slips into “the Hell of her self-consciousness,” somewhere “afar” from here. Long periods of silence. Shrieks, curses, silence again. She grips something in her right hand so tightly that her fingernails sink into her palms. We’re never told what. It is an image and a result of her insatiable acquisitiveness. When she’s finally destroyed so that she appears to the narrator as “death living,” a positive negation, an absolutely artificial embodiment of Nothingness, she is taken to the House of the Dead where countless others yet sleep their judgment sleep. She is placed upon a cold bed of white sheets, and her gripping hand is severed off clean. Adam and Eve assure us that it will, in ages to come, grow back once more. We hear nothing more of Lilith’s judgment.

Second, the total, mysterious power of the divine over judgment. Terse though it is, much of the intense dialogue between Mara and Lilith is consumed with Lilith’s protests against relinquishing her complete autonomy. She insists that she’d rather make herself, even if it means endless suffering. She accuses Mara of being a slave to “Him.” Come what may, she asserts, at least she will act in accordance with her own nature. “You do not know your nature,” retorts Mara. “You are not the Self you imagine.” When, by ineffable judgment, Lilith is “compelled” to admit that she is not her own creator—when, that is, she finally glimpses her “true self”—she clings still tighter to the sheer power of her will: “You might be able to torture me, I don’t know, but you will never compel me to do anything against my will!” Mara’s response is a thoroughly dyothelitist one:

Such a compulsion would be without value. But there is a light that goes deeper than the will, a light that lights up the darkness behind it: that light can change your will, can make it truly yours and not another’s—not the Shadow’s. Into the created can pour itself the creating will, and so redeem it!

At length, Lilith softens ever so slightly, and Mara demands that she release what she’s clutching in her hand. “You think so,” returns Lilith, “but I know I cannot open my hand!” Mara returns: “I know you better than you know yourself, and I know you can.”

This whole harrowing exchange illustrates not merely that an author can attain dramatic tension even when the end is known; though it shows that too. What’s most striking is that the end is known because the “divine” character or guide is never simply a character among other characters. The divine is at once actor and author, character and stage, and so always knows more than any individual character presumes to know. That, I think, is the mystery of judgment in MacDonald. Von Balthasar, for all his affront against presumption, courts a presumption as old as Augustine himself: he presumes to know, time and again, that the bare fact that human persons rebel against and reject God in this life somehow gives us privileged access to the fundamental nature of human freedom itself—of its final and absolute possibilities. But why should we presume that our current state is really revelatory of the basic, perhaps undetectable structures and subtleties of human nature, particularly of the human person as such? Whence comes this unassailable insight into the abyss of the human soul? Did we create it? Divine judgment, says MacDonald, is exactly God’s destruction of “what we call our ‘selves’.” It is His perfection of every human individual qua individual. We do not even know enough of ourselves to know we cannot fully trust the power of His inscrutable judgment to save all.

At the end of “The Wise Woman,” another of his fairytales, MacDonald’s narrator admits he cannot say how any of the tale occurred. He says “it was a result of the interaction of things outside and things inside, of the wise woman’s skill, and the silly child’s folly.” And if “this does not satisfy my questioner,” he concludes, “I can only add, that the wise woman was able to do far more wonderful things than this.” For the Wise Woman, God, there are no limits, Edith Stein might say, to Her infinite resourcefulness over all She has made. Or, as Adam says near the end of Lilith, “He can save even the rich!”

2. Presumption of incertitude.

Von Balthasar judged it presumptuous to maintain any sort of certainty about the Final Act. About this, scriptural revelation rebuffs every forceful attempt at “system-building,” every speculative storming of the gates of Heaven in order to attain an objective vantage from which to deliver some grand synthesis of all things in the end. It might seem that MacDonald falls right in line on this crucial point. He too has little patience for rigid dogmatic pronouncements (more so, indeed, than von Balthasar would generally). He even claims that his own “sequences” are not aimed “at logical certainty”; that is, he is not interested in “proving” his view as much as he is in “showing” it forth. Now, his point is importantly different from von Balthasar’s: MacDonald believes that truth can be properly discerned only by a true person. So “to see a truth, to know what it is, to understand it, and to love it are all one thing.” It’s a fairly Platonic idea. Like knows like, and you cannot know truth—especially divine truth—without being the sort of person, having the sort of character, that knows itself, as it were, in knowing truth (MacDonald thinks the further Christian idea that Truth is diviny-human person only exacerbates the irreducibly personal character of perceiving truth). You must be kin to have ken.

That the truth revealed resists any easy speculative synthesis, though, does not lead MacDonald where it leads von Balthasar, and certainly not about matters eschatological. Quite the opposite. Since knowing the truth must always, for MacDonald, mean knowing the truth for oneself—seeing that it is so—then when you come to so perceive it, you do so in the most intimate sense imaginable. Particularly when it has to do with the Father revealed in and as the face of Jesus Christ, you come to know the truth like you know a brother (the Son) and a Father, and through their common Spirit in you (1 Cor 1–2). This means that when statements about God take an absolute form, they need not be the result of speculative, scientific theology (as von Balthasar presumes). They might rather be like saying, “I know my father, and I know he would never do that.” Did you arrive at that kind of certainty by some speculative enterprise? Is it not something still more subtle, something yet un-systematic exactly because it is intensely personal? Don’t you know absolutes about those closest to you because you know their character, you know them? The degree to which you do not is the degree to which you might have trust issues.

This is why MacDonald prefers to characterize both us and God in terms of “childlikeness.” In his sermon, “The Child in the Midst” (on Mk 9.33-7), he asserts that Jesus tells us to become like a child not because children blindly obey parents, but because God himself is like a child. “God never tells us to become what He Himself is not first.” Rather literally, of course, God became a child in Christ’s birth. But that He did so, and that he commends to us childlikeness as what ought to be imitated, means He too is essentially childlike. We have here two immediate reasons MacDonald chides anyone who considers God overly preoccupied with our alleged presumption. First, we are to be like children, and children often show the least apprehension by boldly (we might say “with confidence,” per John) posing questions or proffering answers, especially when it has to do with the people they know best. A child so trusts her parent that even if she utters some hyperbole, she knows this would constitute no offense to the “dignity” or propriety of her mother. Particularly if she knows her mother is good. Second, since God himself is childlike, He does not worry himself over His royal majesty like a petty monarch. “We are careful, in our unbelief, over the divine dignity, of which he is too grand to think.” It is not God who is afraid of our presumption. We are ones cowering, afraid of being sent away just as the children were barred from Jesus by his disciples.

But notice: when we fear that our imagination of God’s goodness might be too good, too presumptuous for God, we are guilty of imagining Christ in the figure of his ignorant disciples. We are guilty, that is, of rendering a rather unfavorable judgment on His character such that He could never abide little children. We could leger many objections to von Balthasar’s view that hope must exclude certainty. We might point out, for instance, that this is in fact not true of dynamics of theological hope. Hope need not preclude certainty of outcomes. I know that every dead body will one day be raised, and I know that the unjust shall suffer punishment for sin—are these then no longer objects of hope? Of course they are. As Hebrews 11.1 teaches, hope is grounded in faith, and “faith is assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen.” Again, as Paul says in Romans 8.24–5, hope is not opposed to being certain that something will occur; it opposes only the realization of that something here and now. You don’t have hope if the object of hope stands before your eyes; but if it does not, and if you do not know how it will come to pass, then it remains a proper object of hope. But that is quite different from saying you don’t know what it is that will somehow come to be at all.

I could continue with several other points in criticism of von Balthasar’s position. But really, I think MacDonald has hit on the most basic issue in von Balthasar when he defends the “imaginative, hope-filled child” in the face of the “dull disciple” and his protests that no one can know what is not explicitly revealed. “What should I think of my child, if I found that he limited his faith in me and hope from me to the few promises he had heard me utter!” (Unspoken Sermons, “The Higher Faith”). In other words, the very refusal to claim certainty, especially when it implicates the moral integrity of the Father, is itself a rather staggering judgment against the Father. In the Parable of the Talents (Mt 25.14ff.), the sin of the wicked servant is precisely that he presumed to know the character of the Master, and so refrained from action: “I knew you were a harsh man, reaping where you did not sow and gathering where you did not scatter seed.” “Oh, you knew, did you, that I was that way?” Whatever you think the Father might do reveals what you think the Father is like. We know this too from experience of personal intimacy. If someone told me that my father might have killed a man, and I say, “Well, I don’t know that he did, but he might well have”—then what does that say about my opinion of my own father? If you think someone capable of doing some evil, or at least something less than the best, you are, despite your intentions, judging the moral nature of that person. This is what MacDonald thinks we do even if we merely think God might not save everything He chose freely to create. That very suspension of judgment judges God, all the more so if we openly affirm, as von Balthasar does, that God possesses the power to save all. Von Balthasar can protest all he likes that everyone else is a “knower” while he alone resides within the bounds of proper hope, but his too is a presumptuous judgment. He is not neutral; he has claimed to know what is possible of God, what is within his power, what constitute real possibilities for God. And this position seems to me, at least, all the more disingenuous and deceptive, even, in that it renders its judgments under the pretense of pious restraint.

MacDonald gives the lie to von Balthasar’s claim. No one truly refrains from intruding upon God. And why should they? As MacDonald has it in “The Higher Faith”: “To say that we must wait for the other world, to know the mind of him who came to this world to give himself to us, seems to me the foolishness of a worldly and lazy spirit. The Son of God is the Teacher of men, giving to them of his Spirit—that Spirit which manifests the deep things of God, being to a man the mind of Christ [cf. 1 Cor 2.16]. The great heresy of the Church of the present day is unbelief in this Spirit.”

Read more posts like "George MacDonald against Hans Urs von Balthasar on Universal Salvation" at The Showbear Family Circus.

August 25, 2020

Dusk’s Heart

Jordan Daniel Wood over at The Showbear Family Circus - Lancelot Schaubert's and Tara Schaubert's liberal arts circus. said ::

Gilded soft light

Brooding hue

Illumine the trails to the entrails

Of heart, hearth, a life’s womb

Nothing more lucid than dusk

Nothing pellucid but truth

Soft on the eyes

Soft on the soul

Soft on the universe’s womb

Warm dark gentle welcoming tomb

Brisk wintry evenfall, moon’s soft glow

Axe at the root, trunk on the snow

Breath by the ear

Raging peace in the gloam

Rove we ensemble

Afoot without fear

Crepuscular love

Every day a whole year

Read more posts like "Dusk’s Heart" at The Showbear Family Circus.

August 24, 2020

Night

Will Westmoreland over at The Showbear Family Circus - Lancelot Schaubert's and Tara Schaubert's liberal arts circus. said ::

I hear the laughter, and I think sometimes the whispers, of ancient Native American children late some nights when I’m sitting on my back porch smoking cigs. This is not some tired stab at the Southern Gothic supernatural. I mean this is Oxford, one of the birthplaces of American Gothica, but I’ve already used two periods. I’m simply writing about my experiences late some nights, when I’m by myself, listening to, existing along with these laughing spirits and the vast network of wild creatures that lie just beyond the incandescent glow cast by my flood light. I don’t hear these children every night but I’ve witnessed their phenomena more than once. The first time was only a few months ago.

It was an ordinary night, alfresco, and I was in my usual rocker underneath the hanging ferns and myriad spider webs and dirt dauber nests that help number my back porch. I was a bit tired but sleep wasn’t closing in. I wasn’t nodding or drifting. I was awake, lucid. I’m not a drinker, either, so no beer or liquor goggles were skewing my reality. I’m just sitting there listening to the usual nocturnal soundtrack. I can distantly hear the humming of passing cars on Highway 6 below, but it’s background noise at best, and I have to lean into the sound. All in all it’s very peaceful.

I reach down to grab another cig when it happens. I hear distinct and definite laughter issuing from the woods. I freeze. It scares me at first. Body stiffens, erect, and muscles contract, neck hair stands at attention. I feel my heart kick up through my tank top. Baboom, baboom, baboom. I lean forward with head tilted and listen……. Silence. It feels like something’s about to happen but I have no idea what. I think of the ether of old, unseen matter carried on some unseen medium, or things pushing against opposite but equal things to create the cosmic equilibrium. Uneasiness flows like the mighty Sardis spillway as palms moisten. I brush my hair over to the right, out of my eyes. Sudden intense burning sensation on my right knee, JESUS, I dropped my cig. I rub the freshly blistered skin but this only intensifies the burning. Heat and friction do not mix. Things become other things in the presence of extreme heat, I remember, like my newly chaffed skin, black and dry, choked of life or liberty. I pick the cig up, shift it to my left hand and continue to listen.

A couple of minutes go by, and I’m on the edge of my seat, ears up. The sliver in the sky pulses moonblue and lambent, and I consider secret things. Finally I hear the laughter again, and this time it’s louder, clearer. It’s the unmistakable titter of children. But who are they, and why are they playing in my woods at three in the morning? I begin to brainstorm about young kids who might live nearby. There’re actually no youngsters on my street, and most if not all of my neighbors are middle-aged to elderly. A few have grandkids, and they occasionally come to visit, but no children LIVE around here. And even if they did, why’d they be down there in my woods, alone in the middle of the night, giggling to each other in the blackdark? It made no sense at all. I sat and continued to listen and the laughter did not cease. Occasionally I thought I sensed whispers as well, but couldn’t be sure. What I was sure about was that I was no longer alone. And in some weird way that gave me comfort. I didn’t know from what or where these noises were coming, but I felt connected to them, much the same way I feel connected to this rolling hill country that I’ve grown up around and on, those verdant bluffs that scatter sound through distance and topography.

I think, for me, these things are linked, the land and the spirits that hold dominion over them, and every once in a while, when you least expect it, when your frustrations and fears and shortcomings and inertia seem to all collide, on the verge of driving you straight off of the proverbial cliff, you’re reminded that you’re not alone, that the things you endure by day will, by night, reveal some covert and profound meaning. It could come in the evening after a long, soul-crushing day of work in the form of a moment of clarity as you realize how insignificant your suffering is, impressing not a blip on infinity’s radar, a confounding relief that sometimes grips me, or as a laughing spirit in the middle of the night, tempting you to join and aiding your realization that endless potential lies latent within, a double helix of possibilities that don’t bind you to any one person or place or bent of your nature.

With the night comes peace, inspiration, reflection, and above all, understanding. I understand that I’m connected with this land, these spirits and animals. I know that my greatest weakness, all my anxieties and regret about past, present, and future that constrict me by day, will be converted by night through some queer alchemical process, or maybe the First Law of Thermodynamics, into my greatest strength, the confirmation of my own membership among that vast and supernatural matrix of all things physical and spiritual that somehow work in mysterious harmony to create the palpable, distinct atmosphere that is my personal Night.

Something changes as twilight refracts, not length of shadows or angle of sun, but a property ineffable, unable to be explained, like Lorca’s duende that rises from the soles of my feet on up. I’m at once ushered through a narrow space between worlds, from my own plastic reality to a brilliant and resonant place, vibrant with meaning. The darkness insulates me, much like gristle around newly formed bone. It’s only in this peaceful and nonlinear world where I can tap into the past, and simultaneously see the future. Everything is in superposition once the sun goes down. I know that as long as I live, as hopeless and meaningless the daily grind becomes, that, by night, I have an entirely different reality that’s accessible, just waiting for me to dive in. And I will. I do. I hear the laughter, and at first I didn’t know why, but the more I listen, the more I understand.

One night, just a couple months back, I was in my rocker as usual, but on the lookout for whatever had been setting my dogs off in a chorus of howling every few evenings the previous week. I figured it could be one of the creatures captured on the game camera I’d installed the week before. I’d already seen lots of ‘em in the flesh, like deer and possums and raccoons and skunks, just loitering behind the chain-link fence that borders my yard a couple dozen feet into the woods. I’ve had encounters with creatures you wouldn’t expect to find traipsing around your property, like the escaped yearling from a small plot a couple miles away that’s connected to my place by vast and profound woods stretching from my back yard for miles. I’m no whisperer of any sort. It’s because I live on a lot, behind which borders one of the only undeveloped expanses of forest that’s left in a ten-mile radius.

My house is on the west side of town, equidistant between Rowan Oak and Grisham’s old stomping ground. Take one left out of my neighborhood and not another of any kind and you’ll be in Batesville within fifteen to twenty five minutes depending on the weight of your foot. These woods run from the edge of my back yard, unmolested, all the way onto Old Taylor Road, a distance of about 3 miles, and beyond for about another quarter mile or so. After that, and all around, is the new super-developed Oxford, equipped with condos squished into places you wouldn’t think a building crew would be able to squish condos into. The point is, this forest is it as far as natural woodland environment within miles, and all the wildlife from in and around those now-developed areas has been forced into a more concentrated domain, which happens to run up and around my back yard. I’ve seen dozens of red foxes and vixens, coyotes, armadillos, at least one bovine, coons of all kinds, beavers, groundhogs, copperheads, cottonmouths, garter snakes, king snakes, flying squirrels, one bobcat, black widows, brown recluses, red wasp nests aplenty, hornets, those dreaded holes in the ground festering with yellow jackets, the cousin of the red wasp, and above all else, a mountain lion. That’s right. A frickin’ mountain lion.

It happened about a year ago actually, summer of ’18. I was puttering around out back late one night, ‘bout 1:00am, and I’m smoking my cig. I suddenly heard the most terribly visceral, blood-chilling shriek coming from my neighbor’s back yard, to my immediate left, about twenty-five or thirty feet away. It was piercing, and cut through the night like a blade to birthday cake, straight through me. My hair’s beginning to stand just on recall. It sounded exactly like a woman screaming, shrieking for dear life. I honestly thought there was a lady, maybe my sweet next-door neighbor, being attacked in her back yard. You learn a lot about yourself in a time like this. You can either stand up to the challenge, whatever it may be, or you can shy away and scoot like a coward.

I bolt inside faster than I’ve ever run. Collaring composure, I realized I couldn’t just leave her alone out there. I’ve known this lady for fifteen years. She’s a great neighbor, the best you could ask for. I ran into the kitchen and grabbed the only working flashlight out of the four on the kitchen table and ran back out through the French doors, opening both for some reason, before rushing to where I’d stood moments before. The notion of owning a gun occurs for the first time ever. I listen but hear only the silence of stones. I called out her name but nobody responded and there were no footsteps to be heard. Just eerie silence that seemed to grow before dying down again, like your ears popping on a mountain road. I turned the flashlight on and pointed it to the general vicinity of where I’d heard the awful scream but didn’t see anything. I put the light down and looked around. Legs were wobbly. Stomach kept dropping over and over, like a circular rollercoaster that just won’t stop. I was terrified was what I was.

Turning the light onto the spot again I scanned her back yard. Then I saw ‘em, two shining orbs a few inches apart, and froze. They were eyes, and they were looking at me. I dropped the light and tried to gather myself. I picked it back up, swinging it elliptically across her yard and that’s when I spied it. About twenty-five feet away from where I was standing, I watched a huge cat with a head that, in profile, was shaped exactly like my orange house cat. This thing had to be twenty times the size of Mr. Badness. I could not believe what I was seeing, and shined the light long enough to see it smoothly prowl back towards the edge of the woods and out of the circumference of my light, before dropping it yet again and bolting back inside, adrenaline and endorphins fueling me forward.

I busted through the two open doors and slammed ‘em behind me. I was almost in a state of shock, and dashed to my computer to YouTube sounds of all sorts of wild cats in the southern US of A. I eventually found an audio file of a mountain lion screaming, and this was exactly what I’d heard. Once confirmed, I was simply astounded. A mountain lion in Mississippi. I went back outside to find nothing out of the ordinary, the carnivorous creature had cooly crept out of sight, leaving just the woods and all the other less frightening animals I’ve grown inwardly friendly with. I was no longer scared, despite knowing this huge cat which could and would eat me alive at first opportunity was shuffling, creeping around my woods, probably looking at me that second. But the connection had been made. I felt it, some transcendental link to that wild animal, its spirit more precisely, and I began to wonder if those whispers I’d heard were somehow associated with this feeling of correspondence with everything that surrounded me. It was like some mystical union with the land that I love. Words and phrases like animism and anima mundi popped into my mind, and I felt like getting on my knees and talking to plants. I felt I knew the secrets of ancient stones buried all around. I wanted to worship, like some modern-day Druid, the timeless oaks that towered above.

This place where I’ve resided for more than two decades is also home to that endless catalogue of wild creatures and restless spirits, seen and unseen, each possessing a glorious spot, myself included, in the opulent kingdom of evening that blooms and expands by twilight like some cosmic mandala as the nuclear reactor in the sky casts its last merciless ray before being subsumed into the surrounding hill country, like some solar Oreo dipped in milk.

From my back porch bullfrogs consecrate the night as luminous sheet lightning blankets an original sky above, and I hear the circular, unmistakable cadence of the barred owl, probably standing watch from its perch in an elegant American beech, catching a glint of the moon’s ardent offerings before floating off to places clandestine and unseen. I am alive.

Read more posts like "Night" at The Showbear Family Circus.

August 23, 2020

Decimation

Samuel Armen over at The Showbear Family Circus - Lancelot Schaubert's and Tara Schaubert's liberal arts circus. said ::

The bedroom door kept dancing gorgeous van Gogh swirls

while sounds around my windows sang Debussy voiles,

while anything was everything. I tell myself

I’m here to try to sleep despite this fusing force

that surges deep inside my veins. I strain to close

my eyes, and first this warping world is far too bright,

my lids like curtains overwhelmed by light. Each breath

a step against this endless blend of senses. Then:

There’s ten of them all watching me from podiums.

Now comforted to know I’m not alone, I ask

them questions, seeking confidence and clues.

All but one explain their own philosophies, providing me

a sense of truth. Until the last of this crew

says: “Don’t you know that all of us are you?”

Read more posts like "Decimation" at The Showbear Family Circus.

August 12, 2020

“Wishing on Worlds”

Breelyn Shelkey over at The Showbear Family Circus - Lancelot Schaubert's and Tara Schaubert's liberal arts circus. said ::

There is a world

People aware

of surroundings

Acknowledging strangers

Discussing dreams

Changing attitudes

Preserving peace

There is a world

cared by all

No laws

No rules

No need for regulations

Overflowing

genuine reciprocity

There is a world

it could be ours

But our world

survived through screens

has this false mentality

the World Wide Web

is alive

It is simply a processor

nothing more

It will not take action

It will not clean the environment

It will not care for those in need

It will not heal a sick family member

It will not console you after a death

There is a world

it is ours

The online world

where people exist

never as their true selves

Fifty filters

altering appearances

Following

influencers

Facebook “friends”

Tapping twice

Clicking

Scrolling

Swiping

This is our world

our people

forever

logging in

and still

the greatest mystery of all…

teaching them

to log out.

Read more posts like "“Wishing on Worlds”" at The Showbear Family Circus.

Within My Happy-Go-Lucky Head

Gerard Sarnat over at The Showbear Family Circus - Lancelot Schaubert's and Tara Schaubert's liberal arts circus. said ::

I aim to paint poems

but am better suited to

paint houses outside.

Escape into life’s

a goal good writers often

get failing grades at.

On the other hand,

upshots are they’ve deadlier

exit strategies.

Read more posts like "Within My Happy-Go-Lucky Head" at The Showbear Family Circus.

August 5, 2020

“Evaporations at 17,000 Ft”

Breelyn Shelkey over at The Showbear Family Circus - Lancelot Schaubert's and Tara Schaubert's liberal arts circus. said ::

I trekked miles, exceeded elevations

to get high enough to hear myself think

without the clutter

day to day distractions.

To be able to look at one thing

and truly see it, for all it’s worth

its purest form.

Mountains stained orange,

defined by rusty veins.

My breath lingers as I exhale

Smoke stacks dance from scattered cabins

I wonder how they live

If their lives are as peaceful as mine

in this moment.

I imagine they wake up,

to sun creeping in split drapes,

the soft creaks of earth shifting beneath oak.

I imagine they say good morning to the trees

and the vast pines smile, and sway back.

I imagine there is only the sound of the fire, crackling

a pot of tea, whistling.

What I imagine is a want for myself,

tranquility.

But a cabin in the woods cannot stop the mind

from racing, blurring a beautiful forest

into a solid green backdrop.

I climbed 17,000 Ft

to meet my clearest self.

Read more posts like "“Evaporations at 17,000 Ft”" at The Showbear Family Circus.

Airplane Mode

Gerard Sarnat over at The Showbear Family Circus - Lancelot Schaubert's and Tara Schaubert's liberal arts circus. said ::

“A poet…manages, in a lifetime of standing out in thunderstorms,

to be struck by lightning five or six times.”

— Randall Jarell

Gathering kindling —

silver tin can flies above

against black sky– thwack!

Read more posts like "Airplane Mode" at The Showbear Family Circus.

August 1, 2020

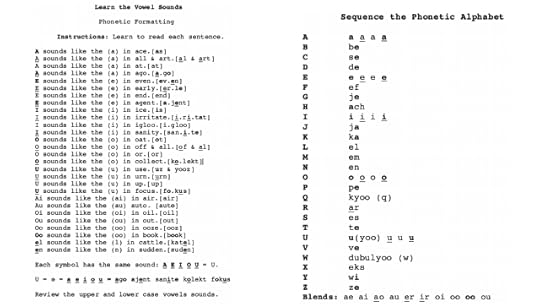

Reading and Decoding English

Dennis Brooks over at The Showbear Family Circus - Lancelot Schaubert's and Tara Schaubert's liberal arts circus. said ::

Reading and Decoding English 8

Letter

2.3 Desirous of Glory

If you know people who have Dyslexia, help them learn to

read starting with this column. It takes patiences to teach them the individual

sounds.

This is an excerpt from Title: Frankenstein or The Modern Prometheus by Mary Wollstonecraft (Godwin) Shelley

Wel, thez ar usles

komplants; I shal sertanle find no

frend on the wid oshan, nor even her in

Arkanjel, among merchants

and semen. Yet som felingz, unallied too the dros

ov human nachur, bet even in

thez ruged bosomz. Mi lootenant,

for instans, iz a man ov wonderful kuraj and

enterpriz; he iz madle dezirus ov glore,

or rather, too word mi fraz mor

karakteristikale, ov advansment in hiz professhon.

He iz an Englishman, and in the midst ov nashonal

and professhonal prejudisez, unsofend

by kultivashon, retansz som

ov the nobelest endouments ov humanite. I first

bekam akwanted with him on bord a hwal

vessel; finding that he waz unemploid

in this site, I ezile engajd him too asist

in mi enterpriz.

The master iz a person ov an eksselent dispozishon and iz remarkabel in the ship for hiz gentlenes and the mildnes ov hiz dissiplin. This sirkumstans, aded too hiz wel-non integrite and dauntles kurej, mad me vere dezirus too engaj him. A yooth pasd in solitud, mi best yearz spent under yor jentel and feminin fosterej, haz so refind the groundwork ov mi karakter that I kannot overkom an intens distast too the uzhooal brootalite exksersizd on bord ship: I hav never belevd it too be nesesare, and hwen I herd ov a mariner ekwalle noted for hiz kindlines ov hart and the respekt and obedeens pad too him bi hiz croo, I felt miself pekyoolyarle forchoonat in being abul too sekyur hiz servisez.

Letter

2.3 Desirous of Glory

Well, these are useless complaints; I

shall certainly find no friend on the wide ocean, nor even here in Archangel,

among merchants and seamen. Yet some feelings, unallied to the dross of human

nature, beat even in these rugged bosoms. My lieutenant, for instance, is a man

of wonderful courage and enterprise; he is madly desirous of glory, or rather,

to word my phrase more characteristically, of advancement in his profession. He

is an Englishman, and in the midst of national and professional prejudices, unsoftened

by cultivation, retains some of the noblest endowments of humanity. I

first became acquainted with him on board a whale vessel; finding that he was

unemployed in this city, I easily engaged him to assist in my enterprise.

The master is a person of an excellent disposition and is remarkable in the ship for his gentleness and the mildness of his discipline. This circumstance, added to his well-known integrity and dauntless courage, made me very desirous to engage him. A youth passed in solitude, my best years spent under your gentle and feminine fosterage, has so refined the groundwork of my character that I cannot overcome an intense distaste to the usual brutality exercised on board ship: I have never believed it to be necessary, and when I heard of a mariner equally noted for his kindliness of heart and the respect and obedience paid to him by his crew, I felt myself peculiarly fortunate in being able to secure his services.

Featured Download: CLICK HERE to unlock the methods for preparing your life for creative inspiration and visionary change.

Read more posts like "Reading and Decoding English" at The Showbear Family Circus.